Jean-Léon Gérôme: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 909908712 by Julian von Bredow (talk)rephrasing, add:references; image should be kept here, no reason to delete |

|||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

===Orientalism=== |

===Orientalism=== |

||

{{unreferenced section|date=August 2017}} |

{{unreferenced section|date=August 2017}} |

||

In 1856, he visited [[Egypt]] for the first time. Gérôme's recurrent itinerary followed the classic grand tour of most occidental visitors to the Orient; up the Nile to Cairo, across to Fayoum, then further up the Nile to Abu Simbel, then back to Cairo, across the Sinai Peninsula through Sinai and up the Wadi el-Araba to the Holy land, Jerusalem and finally Damascus.<ref>Gerald M. Ackerman: Jean-Léon Gérôme: Eight Oil Sketches. 5 December 2004</ref>This would herald the start of many orientalist paintings depicting Arab religion, genre scenes and North African landscapes. In an autobiographical essay of 1878, Gérôme described how important oil sketches made on the spot were for him: "even when worn out after long marched under the bright sun, as soon as our camping spot was reached I got down to work with concentration. But Oh! How many things were left behind of which I carried only the memory away! And I prefer three touches of colour on a piece of canvas to the most vivid memory, but one had to continue on with some regret."<ref>Gérôme, Notes, "J. L. Gérôme á la montée de sa carrière, fait la balance", in: ''Bulletin de la société d'agriculture, lettres, sciences et arts de la Haute-Saône'', 1980, pp. 1–30</ref> He did not only gather themes, artefacts and costumes for his oriental scenes, but also made oil studies from nature for their backgrounds. Several of these quick sketches are filled with details that exceed his wished for three touches of colour. |

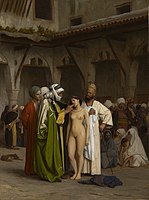

In 1856, he visited [[Egypt]] for the first time. Gérôme's recurrent itinerary followed the classic grand tour of most occidental visitors to the Orient; up the Nile to Cairo, across to Fayoum, then further up the Nile to Abu Simbel, then back to Cairo, across the Sinai Peninsula through Sinai and up the Wadi el-Araba to the Holy land, Jerusalem and finally Damascus.<ref>Gerald M. Ackerman: Jean-Léon Gérôme: Eight Oil Sketches. 5 December 2004</ref>This would herald the start of many orientalist paintings depicting Arab religion, genre scenes and North African landscapes. Among them are several paintings of naked women, in which the Oriental setting served as a pretext to depict nudity. His eroticized scenes of [[The Slave Market]], The Large Pool of Bursa, [[The Snake Charmer]], or The Harem Bath, e.g., are considered by many contemporary art historians and scholars of the Middle East not to represent the reality of the Middle East, but as products of European men's erotic fantasies.<ref>e.g. Nochlin (1983); Toledano (1998, 4–6); Lees (2012)</ref> |

||

[[File:Jean-Léon Gérôme - The Slave Market - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|left|An eroticized scene depicting nude Oriental slaves <br>[[Jean-Léon Gérôme]] – ''The Slave Market'']] |

|||

In an autobiographical essay of 1878, Gérôme described how important oil sketches made on the spot were for him: "even when worn out after long marched under the bright sun, as soon as our camping spot was reached I got down to work with concentration. But Oh! How many things were left behind of which I carried only the memory away! And I prefer three touches of colour on a piece of canvas to the most vivid memory, but one had to continue on with some regret."<ref>Gérôme, Notes, "J. L. Gérôme á la montée de sa carrière, fait la balance", in: ''Bulletin de la société d'agriculture, lettres, sciences et arts de la Haute-Saône'', 1980, pp. 1–30</ref> He did not only gather themes, artefacts and costumes for his oriental scenes, but also made oil studies from nature for their backgrounds. Several of these quick sketches are filled with details that exceed his wished for three touches of colour. |

|||

Gérôme's reputation was greatly enhanced at the Salon of 1857 by a collection of works of a more popular kind: the ''Duel: after the Masked Ball'' ([[Château de Chantilly|Musée Condé]], [[Chantilly, Oise|Chantilly]]), ''Egyptian Recruits crossing the Desert'', ''Memnon and Sesostris'' and ''Camels Watering'', the drawing of which was criticized by [[Edmond François Valentin About|Edmond About]]. |

Gérôme's reputation was greatly enhanced at the Salon of 1857 by a collection of works of a more popular kind: the ''Duel: after the Masked Ball'' ([[Château de Chantilly|Musée Condé]], [[Chantilly, Oise|Chantilly]]), ''Egyptian Recruits crossing the Desert'', ''Memnon and Sesostris'' and ''Camels Watering'', the drawing of which was criticized by [[Edmond François Valentin About|Edmond About]]. |

||

| Line 174: | Line 177: | ||

*Benezit E. - ''Dictionnaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs et Graveurs'' - [[Librairie Gründ]], Paris, 1976; {{ISBN|2-7000-0156-7}} (in French) |

*Benezit E. - ''Dictionnaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs et Graveurs'' - [[Librairie Gründ]], Paris, 1976; {{ISBN|2-7000-0156-7}} (in French) |

||

*[[Laurence des Cars]], Dominque de Font-Rélaux and Édouard Papet (ed.), The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme, (1824–1904), Paris: SKIRA, 2010 |

*[[Laurence des Cars]], Dominque de Font-Rélaux and Édouard Papet (ed.), The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme, (1824–1904), Paris: SKIRA, 2010 |

||

*Lees, Sarah. 2012. “Jean-Léon Gérôme: Slave Market”. In ''Nineteenth-century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute'', edited by S. Lees. 359–363. Williamstown, Mass: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*Nochlin, Linda. 1983. “The Imaginary Orient”. ''Art in America'' 71(5): 118–31, 187–91. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*Toledano, Ehud R. 1998. ''Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle East''. Seattle/London: University of Washington Press. |

|||

*Turner, J. – ''[[Grove Dictionary of Art]]'' – Oxford University Press, USA; new edition (January 2, 1996); {{ISBN|0-19-517068-7}} |

*Turner, J. – ''[[Grove Dictionary of Art]]'' – Oxford University Press, USA; new edition (January 2, 1996); {{ISBN|0-19-517068-7}} |

||

*{{cite book | title=Jean-Léon Gérôme : peintre, sculpteur et graveur; ses oeuvres conservées dans les collections françaises et privées| last=Catalogue of the exhibition in the Musée de Vésoul| date=August 1981| publisher=Ville de Vésoul}} |

*{{cite book | title=Jean-Léon Gérôme : peintre, sculpteur et graveur; ses oeuvres conservées dans les collections françaises et privées| last=Catalogue of the exhibition in the Musée de Vésoul| date=August 1981| publisher=Ville de Vésoul}} |

||

Revision as of 16:49, 12 August 2019

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2014) |

Jean-Léon Gérôme | |

|---|---|

Undated photo of Gérôme by Nadar, published in 1900 | |

| Born | 10 May 1824 |

| Died | 10 January 1904 (aged 79) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | Paul Delaroche, Charles Gleyre |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, teaching |

| Movement | Academicism, Orientalism |

Jean-Léon Gérôme (11 May 1824 – 10 January 1904) was a French painter and sculptor in the style now known as academicism. The range of his oeuvre included historical painting, Greek mythology, Orientalism, portraits, and other subjects, bringing the academic painting tradition to an artistic climax. He is considered one of the most important painters from this academic period. He was also a teacher with a long list of students.

Biography

Early life

Jean-Léon Gérôme was born at Vesoul, Haute-Saône. He went to Paris in 1840 where he studied under Paul Delaroche, whom he accompanied to Italy (1843–44). He visited Florence, Rome, the Vatican and Pompeii, but he was more attracted to the world of nature. Taken by a fever, he was forced to return to Paris in 1844. On his return, he followed, like many other students of Delaroche, into the atelier of Charles Gleyre and studied there for a brief time. He then attended the École des Beaux-Arts. In 1846 he tried to enter the prestigious Prix de Rome, but failed in the final stage because his figure drawing was inadequate.

His painting, The Cock Fight (1846), is an academic exercise, depicting a nude young man and a lightly draped young woman with two fighting cocks, the Bay of Naples in the background. He sent this painting to the Salon of 1847, where it gained him a third-class medal. This work was seen as the epitome of the Neo-Grec movement that had formed out of Gleyre's studio (such as Henri-Pierre Picou (1824–1895) and Jean-Louis Hamon), and was championed by the influential French critic Théophile Gautier.

Gérôme abandoned his dream of winning the Prix de Rome and took advantage of his sudden success. His paintings The Virgin, the Infant Jesus and St John (private collection) and Anacreon, Bacchus and Cupid (Musée des Augustins, Toulouse, France) took a second-class medal in 1848. In 1849, he produced the paintings Michelangelo (also called In his studio) (now in private collection) and A portrait of a Lady (Musée Ingres, Montauban).

In 1851, he decorated a vase, later offered by Emperor Napoleon III of France to Prince Albert, now part of the Royal Collection at St. James's Palace, London. He exhibited Bacchus and Love, Drunk, a Greek Interior and Souvenir d'Italie, in 1851; Paestum (1852); and An Idyll (1853).

Important commissions

In 1852, Gérôme received a commission by Alfred Emilien Comte de Nieuwerkerke, Surintendant des Beaux-Arts to the court of Napoleon III, for the painting of a large historical canvas, the Age of Augustus. In this canvas he combines the birth of Christ with conquered nations paying homage to Augustus. Thanks to a considerable down payment, he was able to travel in 1853 to Constantinople, together with the actor Edmond Got. This would be the first of several travels to the East: in 1854 he made another journey to Greece and Turkey[3] and the shores of the Danube, where he was present at a concert of Russian conscripts, making music under the threat of a lash.

In 1853, Gérôme moved to the Boîte à Thé, a group of studios in the Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, Paris. This would become a meeting place for other artists, writers and actors. George Sand entertained in the small theatre of the studio the great artists of her time such as the composers Hector Berlioz, Johannes Brahms and Gioachino Rossini and the novelists Théophile Gautier and Ivan Turgenev.

In 1854, he completed another important commission of decorating the Chapel of St. Jerome in the church of St. Séverin in Paris. His Last communion of St. Jerome in this chapel reflects the influence of the school of Ingres on his religious works.

To the exhibition of 1855 he contributed a Pifferaro, a Shepherd, A Russian Concert, and The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ. The last was somewhat confused in effect, but in recognition of its consummate rendering the State purchased it. However the modest painting, A Russian Concert (also called Recreation in the Camp) was more appreciated than his huge canvases.

Orientalism

In 1856, he visited Egypt for the first time. Gérôme's recurrent itinerary followed the classic grand tour of most occidental visitors to the Orient; up the Nile to Cairo, across to Fayoum, then further up the Nile to Abu Simbel, then back to Cairo, across the Sinai Peninsula through Sinai and up the Wadi el-Araba to the Holy land, Jerusalem and finally Damascus.[4]This would herald the start of many orientalist paintings depicting Arab religion, genre scenes and North African landscapes. Among them are several paintings of naked women, in which the Oriental setting served as a pretext to depict nudity. His eroticized scenes of The Slave Market, The Large Pool of Bursa, The Snake Charmer, or The Harem Bath, e.g., are considered by many contemporary art historians and scholars of the Middle East not to represent the reality of the Middle East, but as products of European men's erotic fantasies.[5]

Jean-Léon Gérôme – The Slave Market

In an autobiographical essay of 1878, Gérôme described how important oil sketches made on the spot were for him: "even when worn out after long marched under the bright sun, as soon as our camping spot was reached I got down to work with concentration. But Oh! How many things were left behind of which I carried only the memory away! And I prefer three touches of colour on a piece of canvas to the most vivid memory, but one had to continue on with some regret."[6] He did not only gather themes, artefacts and costumes for his oriental scenes, but also made oil studies from nature for their backgrounds. Several of these quick sketches are filled with details that exceed his wished for three touches of colour.

Gérôme's reputation was greatly enhanced at the Salon of 1857 by a collection of works of a more popular kind: the Duel: after the Masked Ball (Musée Condé, Chantilly), Egyptian Recruits crossing the Desert, Memnon and Sesostris and Camels Watering, the drawing of which was criticized by Edmond About.

In 1858, he helped to decorate the Paris house of Prince Napoléon Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte in the Pompeian style. The prince had bought his Greek Interior (1850), a depiction of a brothel also in the Pompeian manner.

In Caesar (1859) Gérôme tried to return to a more severe class of work, the painting of Classical subjects, but the picture failed to interest the public. Phryne before the Areopagus, King Candaules and Socrates finding Alcibiades in the House of Aspasia (1861) gave rise to some scandal by reason of the subjects selected by the painter, and brought down on him the bitter attacks of Paul de Saint-Victor and Maxime Du Camp. At the same Salon he exhibited the Egyptian Chopping Straw, and Rembrandt Biting an Etching, two very minutely finished works.

He married Marie Goupil (1842–1912), the daughter of the international art dealer Adolphe Goupil. They had four daughters and one son. Upon his marriage he moved to a house in the Rue de Bruxelles, close to the music hall Folies Bergère. He expanded it into a grand house with stables with a sculpture studio below and a painting studio on the top floor.

He started an independent atelier at his house in the Rue de Bruxelles between 1860 and 1862.

Atelier at Beaux-Arts

Between 1864 and 1904, more than 2,000 students received at least some of their art education through Gérôme's atelier at the École des Beaux-Arts. Places in Gérôme's atelier were limited, keenly sought and highly competitive. Only the very best students were admitted and aspirants considered it an honour to be selected. Gérôme progressed his students through drawing from antique works, casts and followed by life study with live models generally selected on the basis of their physique, but occasionally for their expression in exercises known as the academie. The sequence was that they drew parts of a bust before the entire bust and then parts of the live model before preparing full figures. Only when they had mastered sketching were they permitted to work in oils. In his school, the floor sloped so that students could gain a view of the model from the rear of the room. They were also taught to draw clearly and correctly before consideration of tonal qualities. Students sat around any model in order of seniority, with the more senior students towards the rear so that they could draw the full figure, while the more junior members sat towards the front and concentrated on the bust or other part of the anatomy.[7]

According to John Milner, who studied with Gérôme, his atelier was the most "riotous" and "lewd" of all the studios at Beaux-Arts. There students were treated to bizarre initiation rites which included such things as slashing each other's canvases, throwing students down stairs, out of windows, and onto upturned stools, staging fencing matches on the model's dais, in the nude and with paintbrushes loaded with paint.[8]

Gérôme attended every Wednesday and Saturday, demanding punctilious attendance to his instructions. His reputation as a severe critic was well-known. One of his students, the American, Stepen Wilson Van Shaick, commented that Gérôme was "merciless in judgement" yet possessed a "singular magnetism."[9] Nevertheless, Gérôme's atelier was the only studio that conferred the master's cachet on its students. Although Gérôme was very demanding of his students, he offered them considerable assistance outside Beaux-Arts; including inviting them to his personal studio, making recommendations to the Salon on their behalf, and encouraging them to study with his colleagues.[10]

Honours

Gérôme was elected, on his fifth attempt, a member of the Institut de France in 1865. Already a knight in the Légion d'honneur, he was promoted to an officer in 1867. In 1869, he was elected an honorary member of the British Royal Academy. The King of Prussia Wilhelm I awarded him the Grand Order of the Red Eagle, Third Class. His fame had become such that he was invited, along with the most eminent French artists, to the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

He was appointed as one of the three professors at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He started with sixteen students, most who had come over from his own studio. His influence became extensive and he was a regular guest of Empress Eugénie at the Imperial Court in Compiègne.

The theme of his Death of Caesar (1867) was repeated in his historical canvas The Execution of Marshal Ney, that was exhibited at the Salon of 1868, despite official pressure to withdraw it as it raised painful memories.

Gérôme returned successfully to the Salon in 1873 with his painting L'Eminence Grise (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), a colorful depiction of the main stair hall of the palace of Cardinal Richelieu, popularly known as the Red Cardinal (L'Eminence Rouge), who was France's de facto ruler under King Louis XIII beginning in 1624. In the painting, François Le Clerc du Trembly, a Capuchin friar dubbed L'Eminence Grise (the Gray Cardinal), descends the ceremonial staircase immersed in the Bible while subjects either bow before him or fix their gaze on him. As Richelieu's chief adviser, L'Eminence Grise was called "the power behind the throne," which became the known definition of his title.[11]

When he started to protest and show a public hostility to "decadent fashion" of Impressionism, his influence started to wane and he became unfashionable. But after the exhibition of Manet in the Ecole in 1884, he eventually admitted that "it was not so bad as I thought." [citation needed]

In 1896 Gérôme painted Truth Coming Out of Her Well, an attempt to describe the transparency of an illusion. He therefore welcomed the rise of photography as an alternative to his photographic painting. In 1902, he said "Thanks to photography, Truth has at last left her well."[citation needed]

Death

Jean-Léon Gérôme died in his atelier on 10 January 1904. He was found in front of a portrait of Rembrandt and close to his own painting Truth Coming Out of Her Well. At his own request, he was given a simple burial service without flowers. But the Requiem Mass given in his memory was attended by a former president of the Republic, most prominent politicians, and many painters and writers. He was buried in the Montmartre Cemetery in front of the statue Sorrow that he had cast for his son Jean who had died in 1891.

He was the father-in-law of the painter Aimé Morot.

Sculpture

Gérôme was also successful as a sculptor. His first work was a large bronze statue of a gladiator holding his foot on his victim, shown to the public at the Exposition Universelle of 1878. This bronze was based on the main theme of his painting Pollice verso (1872). The same year he exhibited a marble statue at the Salon of 1878, based on his early painting Anacreon, Bacchus and Cupid (1848).

Aware of contemporary experiments of tinting marble (such as by John Gibson) he produced Dancer with Three Masks (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen ), combining movement with colour (exhibited in 1902). His tinted group Pygmalion and Galatea provided his inspiration for several paintings in which he depicted himself as the sculptor who could turn marble into flesh, examples of which (c. 1890) are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Smart Museum, Chicago.

Among his other works are Omphale (1887), and the statue of the duc d'Aumale which stands in front of the château of Chantilly (1899).

He started experimenting with mixed ingredients, using for his statues tinted marble, bronze and ivory, inlaid with precious stones and paste. His Dancer was exhibited in 1891. His lifesize statue Bellona (1892), in ivory, bronze, and gemstones, attracted great attention at the exhibition in the Royal Academy of London.

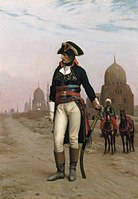

The artist then began a series of Conquerors, wrought in gold, silver and gems: Bonaparte entering Cairo (1897); Tamerlane (1898); and Frederick the Great (1899).

Gallery

Gérôme's notable paintings include (many depict Eastern subjects) :

- The Duel After the Masquerade (1857-1859) in the Walters Art Museum

- Turkish Prisoner (1861)

- Turkish Butcher Boy in Jerusalem (1862)

- Louis XIV and Molière (1863)

- Napoleon in Egypt, ca. 1863

- The Reception of the Siamese Ambassadors at Fontainebleau (1865)

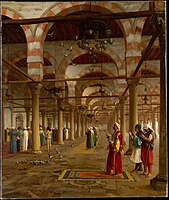

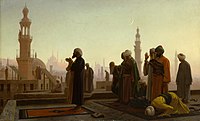

- Prayer in Cairo (1865)

- The Slave Market (c.1866)

- Jerusalem, also called Golgotha, Consumatum Est or The Crucifixion (1867)

- The Execution of Marshal Ney (1868)

- Excursion of the Harem (1869)

- L'Eminence Grise (1873)[12]

- Arnaut and his dog

- The Snake Charmer (1880)

- Pygmalion and Galatea (1890)

- The Birth of Venus (Gérôme) (1890)

An example of his plein-air oil sketches (always with thumbtack holes along the margins of each canvas where they were fastened to a drawing board.

- An encampment before Constantinople 1878

-

Diogenes, 1860, Walters Art Museum

-

Napoleon in Egypt, ca. 1863, Princeton University Art Museum

-

Young Greeks at the Mosque, 1865, this oil on canvas painting portrays Greek Muslim recruits into the Ottoman Janissary corps at prayer in a mosque.

-

Arnaut Smoking, 1865

-

Prayer in Cairo, 1865, depicting worshippers on a rooftop at prayer time

-

Heads of the Rebel Beys at the Mosque of El Hasanein, Cairo, 1866

-

Reception of Le Grand Condé at Versailles, 1878

-

Pygmalion and Galatea, 1890

-

Summer Afternoon on a Lake, ca. 1895

-

Arnaut Blowing Smoke in His Dog's Nose

-

The Large Pool of Bursa

-

On the Desert, The Walters Art Museum

-

Leda and the Swan, 1895

-

Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire, using lion and tiger.[13] This painting by Gérôme was commissioned by William Thompson Walters in 1863.

-

The Carpet Merchant, c. 1887, Minneapolis Institute of Art

-

Bashi-Bazouk, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Prayer in the Mosque, 1871, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Jean-Leon Gerome Pollice Verso, 1872.

See also

References and sources

- References

- ^ "The Duel After the Masquerade". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ "The Tulip Folly". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Rosenthal, Donald A. 1982. Orientalism, the Near East in French painting, 1800–1880. Rochester, N.Y.: Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester. p. 77. ISBN 0918098149

- ^ Gerald M. Ackerman: Jean-Léon Gérôme: Eight Oil Sketches. 5 December 2004

- ^ e.g. Nochlin (1983); Toledano (1998, 4–6); Lees (2012)

- ^ Gérôme, Notes, "J. L. Gérôme á la montée de sa carrière, fait la balance", in: Bulletin de la société d'agriculture, lettres, sciences et arts de la Haute-Saône, 1980, pp. 1–30

- ^ O'Sullivan, N., Aloysius O'Kelly: Art, Nation, Empire, Field Day Publications, 2010 pp 17–21

- ^ Cited in O'Sullivan, N., Aloysius O'Kelly: Art, Nation, Empire, Field Day Publications, 2010 pp 17–18

- ^ Cited in O'Sullivan, N., Aloysius O'Kelly: Art, Nation, Empire, Field Day Publications, 2010 p. 18

- ^ Cited in O'Sullivan, N., Aloysius O'Kelly: Art, Nation, Empire, Field Day Publications, 2010 p. 21

- ^ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: L'Eminence Grise

- ^ "Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: ''L'Eminence Grise''". Mfa.org. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ Millar, Fergus (2006) A Greek Roman Empire: Power and Belief under Theodosius–II (408–450). University of California Press. p. 279. ISBN 0520941411.

- Sources

- Ackerman, Gerald (1986). The life and work of Jean-Léon Gérôme; catalogue raisonné. Sotheby's Publications. ISBN 0-85667-311-0.

- Ackerman, Gerald (2000). Jean-Léon Gérôme. Monographie révisée, catalogie raisonné mis a jour. ACR. ISBN 2-86770-137-6.

- Benezit E. - Dictionnaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs et Graveurs - Librairie Gründ, Paris, 1976; ISBN 2-7000-0156-7 (in French)

- Laurence des Cars, Dominque de Font-Rélaux and Édouard Papet (ed.), The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme, (1824–1904), Paris: SKIRA, 2010

- Lees, Sarah. 2012. “Jean-Léon Gérôme: Slave Market”. In Nineteenth-century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, edited by S. Lees. 359–363. Williamstown, Mass: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

- Nochlin, Linda. 1983. “The Imaginary Orient”. Art in America 71(5): 118–31, 187–91.

- Scott C. Allan and Mary Morton (ed.), Reconsidering Gérôme, Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010, in: Art Bulletin 94 (2012), No. 2, pp. 312–316

- Toledano, Ehud R. 1998. Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle East. Seattle/London: University of Washington Press.

- Turner, J. – Grove Dictionary of Art – Oxford University Press, USA; new edition (January 2, 1996); ISBN 0-19-517068-7

- Catalogue of the exhibition in the Musée de Vésoul (August 1981). Jean-Léon Gérôme : peintre, sculpteur et graveur; ses oeuvres conservées dans les collections françaises et privées. Ville de Vésoul.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gérôme, Jean Léon". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- List of students with examples of work, biography, letters, Gerome image gallery

- Artencyclopedia.com page on Gérôme

- www.jeanleongerome.org near 300 images by the artist

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1906.

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Jean-Léon Gérôme in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

- Jean-Léon Gérôme

- 1824 births

- 1904 deaths

- People from Vesoul

- 19th-century French painters

- French male painters

- 20th-century French painters

- Academic art

- Members of the Académie des beaux-arts

- Recipients of the Order of the Red Eagle

- Burials at Montmartre Cemetery

- Orientalist painters

- Neo-Pompeian painters

- 20th-century French sculptors

- 19th-century French sculptors

- French male sculptors

- Nude art

- Members of the Ligue de la patrie française

- Grand Officiers of the Légion d'honneur

- Honorary Members of the Royal Academy

![Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire, using lion and tiger.[13] This painting by Gérôme was commissioned by William Thompson Walters in 1863.](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/Jean-L%C3%A9on_G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me_-_The_Christian_Martyrs%27_Last_Prayer_-_Walters_37113.jpg/200px-Jean-L%C3%A9on_G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me_-_The_Christian_Martyrs%27_Last_Prayer_-_Walters_37113.jpg)