Fu-Go balloon bomb: Difference between revisions

Changed Metric to Imperial Because: AMERICA |

Tag: possible vandalism |

||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

[[File:342-FH-3B23426 (18160066205).jpg|thumb|right|"Brain Center" of balloon. |alt=Fire balloon controls, showing payload (incendiary bombs) and detachable ballast (sand bags) to maintain altitude.]] |

[[File:342-FH-3B23426 (18160066205).jpg|thumb|right|"Brain Center" of balloon. |alt=Fire balloon controls, showing payload (incendiary bombs) and detachable ballast (sand bags) to maintain altitude.]] |

||

The ''fūsen bakudan'' campaign was |

The ''fūsen bakudan'' campaign was the most earnest of the attacks. The concept was the brainchild of the [[Imperial Japanese Army]]'s Ninth Army's [[Number Nine Research Laboratory]], under Major General [[Sueyoshi Kusaba]], with work performed by Technical Major [[Teiji Takada]] and his colleagues. The balloons were intended to make use of a strong current of winter air that the Japanese had discovered flowing at high altitude and speed over their country, which later became known as the [[jet stream]].<ref name=retaliation>Webber, pp.99–108</ref> |

||

The jet stream reported by [[Wasaburo Oishi]]<ref>{{Citation |

The jet stream reported by [[Wasaburo Oishi]]<ref>{{Citation |

||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

Similarly, when the balloon rose above about {{Convert|38,000|ft|km|abbr=}}, the altimeter activated a valve to vent hydrogen. The hydrogen was also vented if the balloon's pressure reached a critical level.<ref name=retaliation/> |

Similarly, when the balloon rose above about {{Convert|38,000|ft|km|abbr=}}, the altimeter activated a valve to vent hydrogen. The hydrogen was also vented if the balloon's pressure reached a critical level.<ref name=retaliation/> |

||

The control system ran the balloon through three days of flight. |

The control system ran the balloon through three days of flight. By that time, it was likely over the U.S., and its ballast was expended. The final flash of gunpowder released the bombs, also carried on the wheel, and lit a {{convert|64|ft|m|abbr=off|sp=us}} long fuse that hung from the balloon's equator. After 84 minutes, the fuse fired a flash bomb that destroyed the balloon.<ref name=retaliation/> |

||

[[File:342-FH-3B23428 (18160060525).jpg|thumb|right|Still from a movie showing ballast release. |alt=Reconstructed balloon ballast control apparatus at the moment an explosive charge is detonated to release sandbags.]] |

[[File:342-FH-3B23428 (18160060525).jpg|thumb|right|Still from a movie showing ballast release. |alt=Reconstructed balloon ballast control apparatus at the moment an explosive charge is detonated to release sandbags.]] |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

*{{convert|11|lb|kg|adj=on|abbr=}} thermite incendiary bomb consisting of a {{convert|3.75|in|cm|adj=on}} steel tube {{convert|15.75|in|cm}} long containing thermite with an ignition charge of magnesium, [[potassium nitrate]] and [[barium peroxide]]. |

*{{convert|11|lb|kg|adj=on|abbr=}} thermite incendiary bomb consisting of a {{convert|3.75|in|cm|adj=on}} steel tube {{convert|15.75|in|cm}} long containing thermite with an ignition charge of magnesium, [[potassium nitrate]] and [[barium peroxide]]. |

||

The Japanese Imperial Army Noborito Institute cultivated [[anthrax]] and ''[[Yersinia pestis]]''; furthermore, it produced enough [[cowpox]] viruses to infect the |

The Japanese Imperial Army's Noborito Institute cultivated [[anthrax]] and ''[[Yersinia pestis]]''; furthermore, it produced enough [[cowpox]] viruses to infect the entire United States.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.warhistoryonline.com/history/12-warrior-clans-samurai-history-m.html | title=Warrior Clans from the Bloody History of the Japanese Samurai| date=2017-09-16}}</ref> |

||

The |

The deployment of these biological weapon on fire balloons was planned in 1944.<ref>"Igakusya tachi no sosiki hannzai kannto-gun 731 butai", Keiichi Tsuneishi</ref> |

||

The Emperor Hirohito did not admit deployment of biological weapons on the occasion of a report of President Staff Officer Umezu on October 25, 1944. Consequently, the biological warfare was not realized.<ref>"Showa no Shunkan mou hitotsu no seidan", Kazutoshi Hando,1988</ref> |

The Emperor Hirohito did not admit deployment of biological weapons on the occasion of a report of President Staff Officer Umezu on October 25, 1944. Consequently, the biological warfare was not realized.<ref>"Showa no Shunkan mou hitotsu no seidan", Kazutoshi Hando,1988</ref> |

||

Similar, |

Similar, though cruder, balloons were also [[Operation Outward|used by Britain]] to attack Nazi Germany between 1942 and 1944. |

||

== Offensive == |

== Offensive == |

||

Revision as of 07:05, 20 September 2019

| Fu-Go ふ号[兵器] (fugō [heiki]) | |

|---|---|

| |

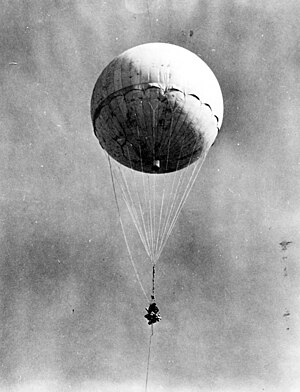

| Shot-down fire balloon reinflated by Americans in California. | |

| Role | Hydrogen balloon |

| National origin | Japan |

| Manufacturer | Imperial Japanese Navy |

| First flight | 1944 |

| Introduction | November 3, 1944 |

| Retired | April 1945 |

| Primary users | Imperial Japanese Navy Imperial Japanese Army |

| Produced | 1944-1945 |

| Number built | over 9,300 |

| Developed into | E77 balloon bomb |

A Fu-Go (ふ号[兵器], fugō [heiki], lit. "Code Fu [Weapon]"), or fire balloon (風船爆弾, fūsen bakudan, lit. "balloon bomb"), was a weapon launched by Japan during World War II. A hydrogen balloon with a load varying from a 33 lb (15 kg) antipersonnel bomb to one 26-pound (12 kg) incendiary bomb and four 11 lb (5.0 kg) incendiary devices attached, it was designed as a cheap weapon intended to make use of the jet stream over the Pacific Ocean and drop bombs on American cities, forests, and farmland. Canada and Mexico also reported fire balloon sightings as well.[1]

The Japanese fire balloon was the first ever weapon possessing intercontinental range[2] (the second being the Convair B-36 Peacemaker and the third being the R-7 ICBM). The Japanese balloon attacks on North America were at that time the longest ranged attacks ever conducted in the history of warfare, a record which was not broken until the 1982 Operation Black Buck raids during the Falkland Islands War.

The balloons were intended to instill fear and terror in the U.S., though the bombs were relatively ineffective as weapons of destruction[3] due to extreme weather conditions.[4]

Overview

From late 1944 until early 1945, the Japanese launched over 9,300 fire balloons, of which 300 were found or observed in the U.S. Despite the high hopes of their designers, the balloons were ineffective as weapons, causing only six deaths (from one single incident) and a small amount of damage. The deaths occurred when the victims decided to touch the balloon, thus causing it to explode.

The Japanese designed two types of balloons. The first was called the "Type B Balloon" and was designed by the Japanese Navy. It was 30 ft (9.1 m) in diameter and consisted of rubberized silk. The type B balloons were sent first and mainly used for meteorological purposes. The Japanese used them to determine the possibility of the bomb-carrying balloons reaching The United States.[5] The second type was the bomb-carrying balloon. Japanese bomb-carrying balloons were 33 ft (10 m) in diameter and, when fully inflated, held about 19,000 cu ft (540 m3) of hydrogen. Their launch sites were located on the east coast of the main Japanese island of Honshū.

Japan released the first of these bomb-bearing balloons on November 3, 1944. They were found in Alaska, Arizona, British Columbia, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Mexico, Michigan,[6] Montana, Nebraska, Nevada,[7] North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Washington, Wyoming, and Yukon Territory.

General Kusaba's men launched over 9,000 balloons throughout the course of the project. The Japanese expected 10% (around 900) of them to reach America, which is also what is currently believed by researchers.[8] About 300 balloon bombs were found or observed in America. It is likely that more balloon bombs landed in unpopulated areas of The United States.

The last one was launched in April 1945.

Origins

The fūsen bakudan campaign was the most earnest of the attacks. The concept was the brainchild of the Imperial Japanese Army's Ninth Army's Number Nine Research Laboratory, under Major General Sueyoshi Kusaba, with work performed by Technical Major Teiji Takada and his colleagues. The balloons were intended to make use of a strong current of winter air that the Japanese had discovered flowing at high altitude and speed over their country, which later became known as the jet stream.[9]

The jet stream reported by Wasaburo Oishi[10] blew at altitudes above 30,000 ft (9.1 km) and could carry a large balloon across the Pacific in three days, over a distance of more than 5,000 miles (8,000 km). Such balloons could carry incendiary and high-explosive bombs to the United States and drop them there to kill people, destroy buildings, and start forest fires.[9]

The preparations were lengthy because the technological problems were acute. A hydrogen balloon expands when warmed by the sunlight, and rises; then it contracts when cooled at night, and descends. The engineers devised a control system driven by an altimeter to discard ballast. When the balloon descended below 30,000 ft (9.1 km), it electrically fired a charge to cut loose sandbags. The sandbags were carried on a cast-aluminium four-spoked wheel and discarded two at a time to keep the wheel balanced.[9]

Similarly, when the balloon rose above about 38,000 feet (12 km), the altimeter activated a valve to vent hydrogen. The hydrogen was also vented if the balloon's pressure reached a critical level.[9]

The control system ran the balloon through three days of flight. By that time, it was likely over the U.S., and its ballast was expended. The final flash of gunpowder released the bombs, also carried on the wheel, and lit a 64 feet (20 meters) long fuse that hung from the balloon's equator. After 84 minutes, the fuse fired a flash bomb that destroyed the balloon.[9]

The balloon had to carry about 1,001 pounds (454 kg) of gear. At first the balloons were made of conventional rubberized silk, but improved envelopes had less leakage. An order went out for ten thousand balloons made of "washi", a paper derived from mulberry bushes that was impermeable and very tough. It was only available in squares about the size of a road map, so it was glued together in three or four laminations using edible konnyaku (devil's tongue) paste – though hungry workers stealing the paste for food created some issues. Many workers were nimble-fingered teenaged school girls.[11] They assembled the paper in many parts of Japan. Large indoor spaces, such as sumo halls, sound stages, and theatres, were required for the envelope assembly.[9]

The bombs most commonly carried by the balloons were:[12]

- Type 92 33-pound (15 kg) high-explosive bomb consisting of 9.5 pounds (4.3 kg) picric acid or TNT surrounded by 26 steel rings within a steel casing 4 inches (10 cm) in diameter and 14.5 inches (37 cm) long and welded to a 11-inch (28 cm) tail fin assembly.

- Type 97 26-pound (12 kg) thermite incendiary bomb using the Type 92 bomb casing and fin assembly containing 11 ounces (310 g) of gunpowder and three 3.3-pound (1.5 kg) magnesium containers of thermite.

- 11-pound (5.0 kg) thermite incendiary bomb consisting of a 3.75-inch (9.5 cm) steel tube 15.75 inches (40.0 cm) long containing thermite with an ignition charge of magnesium, potassium nitrate and barium peroxide.

The Japanese Imperial Army's Noborito Institute cultivated anthrax and Yersinia pestis; furthermore, it produced enough cowpox viruses to infect the entire United States.[13] The deployment of these biological weapon on fire balloons was planned in 1944.[14] The Emperor Hirohito did not admit deployment of biological weapons on the occasion of a report of President Staff Officer Umezu on October 25, 1944. Consequently, the biological warfare was not realized.[15]

Similar, though cruder, balloons were also used by Britain to attack Nazi Germany between 1942 and 1944.

Offensive

A balloon launch organization of three battalions was formed. The first battalion included headquarters and three squadrons totaling 1,500 men in Ibaraki Prefecture with nine launch stations at Ōtsu. The second battalion of 700 men in three squadrons operated six launch stations at Ichinomiya, Chiba; and the third battalion of 600 men in two squadrons operated six launch stations at Nakoso in Fukushima Prefecture. The Ōtsu site included hydrogen gas generating facilities, but the 2nd and 3rd battalion launch sites used hydrogen manufactured elsewhere. The best time to launch was just after the passing of a high-pressure front, and wind conditions were most suitable for several hours prior to the onshore breezes at sunrise. Suitable launch conditions were expected on only about fifty days through the winter period of maximum jet stream velocity, and the combined launch capacity of all three battalions was about 200 balloons per day.[16]

Initial tests took place in September 1944 and proved satisfactory; however, before preparations were complete, United States Army Air Forces B-29 Superfortress planes began bombing the Japanese home islands. The attacks were somewhat ineffectual at first but still fueled the desire for revenge sparked by the Doolittle Raid.

The first balloon was released on November 3, 1944. Major Takada watched as the balloon flew upward and over the sea: "The figure of the balloon was visible only for several minutes following its release until it faded away as a spot in the blue sky like a daytime star." A few balloons carried radiosonde equipment rather than bombs. These balloons were tracked by direction finding stations in Ichinomiya, Chiba, in Iwanuma, Miyagi, in Misawa, Aomori, and on Sakhalin to estimate progress toward the United States.[17]

The Japanese chose to launch the campaign in November; because the period of maximum jet stream velocity is November through March. This limited the chance of the incendiary bombs causing forest fires, as that time of year produces the maximum North American Pacific coastal precipitation, and forests were generally snow-covered or too damp to catch fire easily. On November 4, 1944, a United States Navy patrol craft discovered one of the first radiosonde balloons floating off San Pedro, Los Angeles. National and state agencies were placed on heightened alert status when balloons were found in Wyoming and Montana before the end of November.[18]

The balloons continued to arrive in Alaska, Hawaii, Oregon, Kansas, Iowa, Washington, Idaho, South Dakota, and Nevada (including one that landed near Yerington that was discovered by cowboys who cut it up and used it as a hay tarp,[19] another by a prospector near Elko who delivered it to local authorities on the back of a donkey, and another was shot down by Army Air Forces planes near Reno), as well as Canada in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Alberta, the Yukon, and Northwest Territories.[20] In all, seven fire balloons were turned in to the United States Army in Nevada, Colorado, Texas, Northern Mexico, Michigan, and even the outskirts of Detroit.[21] Army Air Forces or Navy fighters scrambled to intercept the balloons, but they had little success; the balloons flew very high and surprisingly fast, and fighters destroyed fewer than 20.

American authorities concluded the greatest danger from these balloons would be wildfires in the Pacific coastal forests. The Fourth Air Force, Western Defense Command, and Ninth Service Command organized the Firefly Project of 2,700 troops, including 200 paratroopers of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion with Stinson L-5 Sentinel and Douglas C-47 Skytrain aircraft. These men were stationed at critical points for use in fire-fighting missions.[22] The 555th suffered one fatality and 22 injuries fighting fires.

Through Firefly, the military used the United States Forest Service as a proxy agency to combat FuGo. Due to limited wartime fire suppression personnel, Firefly relied upon the 555th as well as conscientious objectors. The operation also unified fire suppression communications among federal and state agencies. The influx of military personnel, equipment, and tactics shaped how the United States Forest Service approached fire suppression in the post War period.[23]

By early 1945, Americans were becoming aware that something strange was going on. Balloons had been sighted and explosions heard, from California to Alaska. Something that appeared to witnesses to be like a parachute descended over Thermopolis, Wyoming. A fragmentation bomb exploded, and shrapnel was found around the crater. A P-38 Lightning shot a balloon down near Santa Rosa, California; another was seen over Santa Monica; and bits of washi were found in the streets of Los Angeles.

In February and March 1945, P-40 fighter pilots from 133 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force Western Air Command operating out of RCAF Patricia Bay (Victoria, British Columbia), intercepted and destroyed two fire balloons,[24] On February 21, Pilot Officer E. E. Maxwell While shot down a balloon, which landed on Sumas Mountain, in Washington State. On March 10, Pilot Officer J. Gordon Patten destroyed a balloon near Saltspring Island, British Columbia.

On March 10, 1945, one of the last paper balloons descended in the vicinity of the Manhattan Project's production facility at the Hanford Site. This balloon caused a short circuit in the power lines supplying electricity for the nuclear reactor cooling pumps, but backup safety devices restored power almost immediately.[25]

Two paper balloons were recovered in a single day in Modoc National Forest, east of Mount Shasta. Near Medford, Oregon, a balloon bomb exploded in towering flames. The Navy found balloons in the ocean. Balloon envelopes and apparatus were found in Montana and Arizona, and inside Canada in Saskatchewan, in the Northwest Territories, and in the Yukon Territory. Eventually, an Army fighter managed to push one of the balloons around in the air and force it to ground intact, where it was examined and filmed. Japanese propaganda broadcasts announced great fires and an American public in panic, declaring casualties in the thousands.[26]

Allied investigation

Despite their low success, the authorities were worried about the balloons. There was the chance that they might get unlucky. Much worse, the Americans had some knowledge that the Japanese had been working on biological weapons,[27] most specifically at the infamous Unit 731 site at Pingfan in northeast China, and a balloon carrying biowarfare agents could be a real threat.

Nobody believed the balloons could have come directly from Japan. It was thought that the balloons must be coming from North American beaches, launched by landing parties from submarines. Wilder theories speculated that they could have been launched from German prisoner of war camps in the U.S., or even from Japanese-American internment centers.[27]

Some of the sandbags dropped by the fusen bakudan were taken to the Military Geology Unit of the United States Geological Survey for investigation. Working with the Military Intelligence Service, the researchers of the Military Geological Unit began microscopic and chemical examination of the sand from the sandbags to determine types and distribution of diatoms and other microscopic sea creatures, and its mineral composition.[28][29] [27] The sand could not be coming from American beaches, nor from the mid-Pacific. It had to be coming from Japan. The geologists ultimately determined that the sand had been taken from the vicinity of Ichinomiya. Aerial reconnaissance then located two of the hydrogen production plants nearby, which were soon destroyed by B-29 bombing raids in April 1945.[28][27].

Press coverup

The bombs caused little damage, but their potential for destruction and fires was large. The bombs also had a potential psychological effect on the American people. The U.S. strategy was to keep the Japanese from knowing of the balloon bombs' effectiveness.

An Associated Press story dated December 18, 1944, stated that the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the military were investigating a 33.5 foot (10.2 m) paper balloon with incendiary attachments found by a wood chopper and his father in a mountainous forested region 17 miles southwest of Kalispell, Montana, on December 11, with a very detailed description of the curious find.[30]

In 1945 Newsweek ran an article titled "Balloon Mystery" in their January 1 issue[31], and a similar story appeared in a newspaper the next day.

The Office of Censorship then sent a message to newspapers and radio stations to ask them to make no mention of balloons and balloon-bomb incidents. They did not want the enemy to get the idea that the balloons might be effective weapons or to have the American people start panicking. Cooperating with the desires of the government, the press did not publish any balloon bomb incidents.[32] Perhaps as a result, the Japanese only learned of one bomb's reaching Wyoming, landing and failing to explode, so they stopped the launches after less than six months.

The press blackout in the U.S. was lifted after the first deaths to ensure that the public was warned, though public knowledge of the threat could have possibly prevented it.[32]

Abandonment

With no evidence of any effect, General Kusaba was ordered to cease operations in April 1945, believing that the mission had been a total fiasco. The expense was large, and in the meantime the B-29s had destroyed two of the three hydrogen plants needed by the project.

The last fire balloon was launched in April 1945.

Single lethal attack

| Killed near Bly, Oregon[33] |

| 1. Elsie Mitchell, age 26, pregnant |

| 2. Edward Engen, age 13 |

| 3. Jay Gifford, age 13 |

| 4. Joan Patzke, age 13 |

| 5. Dick Patzke, age 14 |

| 6. Sherman Shoemaker, age 11 |

On May 5, 1945, a pregnant woman and five children were killed when they discovered a balloon bomb that had landed in the forest of Gearhart Mountain in Southern Oregon. Archie Mitchell was the pastor of the Bly Christian and Missionary Alliance Church. He and his pregnant wife Elsie drove up to Gearhart Mountain with five of their Sunday school students (aged 11–14) to have a picnic. They had to stop at this spot near Bly, Oregon, due to construction and a road closing. Elsie and the children got out of the car at Bly, while Archie drove on to find a parking spot. As Elsie and the children looked for a good picnic spot, they saw a strange balloon lying on the ground. There were two explosions; the boys were killed immediately, and Elsie died as Archie used his hands to extinguish the fire on her clothing. Joan Patzke survived the initial blast, but died later. A bomb disposal expert guessed that the bomb had been kicked.[34][35][36] They were the only people whose deaths were attributed to the balloon bombs deployed on American soil.

Military personnel arrived on the scene within hours, and saw that the balloon still had snow underneath it, while the surrounding area did not. They concluded that the balloon bomb had drifted to the ground several weeks earlier, and had lain there undisturbed until found by the group.

Elsie Mitchell is buried in the Ocean View Cemetery in Port Angeles, Washington. A memorial, the Mitchell Monument, is located at the point of the explosion, 69 miles (111 kilometers) northeast of Klamath Falls in the Mitchell Recreation Area. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2001. Several Japanese civilians have visited the monument to offer their apologies for the deaths that took place here, and several cherry trees have been planted around the monument as a symbol of peace.[36]

Post–World War II

The remains of balloons continued to be discovered after the war. Eight were found in the 1940s, three in the 1950s, and two in the 1960s. In 1978, a ballast ring, fuses, and barometers were found near Agness, Oregon, and are now part of the collection of the Coos Historical & Maritime Museum.[37]

The remains of a balloon bomb were found in Lumby, British Columbia, in October 2014 and detonated by a Royal Canadian Navy ordnance disposal team.[38]

The Canadian War Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, has a full, intact balloon on display.[39]

See also

Notes

- ^ Mikesh, pp.1&21

- ^ "Japan's Secret WWII Weapon: Balloon Bombs". May 27, 2013.

- ^ "Anti-Aircraft Mine & Intercontinental Launching Balloon Bombs Through Jet Stream-Fire balloon-Japanese Balloon Bombs-Terrorist Handbook-on a wind and a prayer | Jet Stream | Anti Aircraft Warfare". Scribd. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ^ Karns, Jameson (March 2017). "A Fire Management Assessment of FuGo". Fire Management Today. 75: 53–57.

- ^ Powles, James (February 2003), "Silent Destruction: Japanese Balloon Bombs", World War II, vol. volume 17 issue 6, pp. 65–66

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Ancona, Gaspar F. (2001). Where The Star Came to Rest. Strasbourg Cedex 2, France: Éditions du Signe. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-2-7468-0317-6.

On January 23, 1945...It landed on the farm of Chris Stein near the intersection of 146th Avenue and 21st Street in northern Allegan County

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "That time in World War II when Japan used a hot air balloon to bomb Oregon and kill six people - Altered Dimensions Paranormal". January 19, 2016.

- ^ Mikesh, p.1

- ^ a b c d e f Webber, pp.99–108

- ^ Lewis, John M. (2003), "Oishi's Observation: Viewed in the Context of Jet Stream Discovery.", Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 84 (3): 357–369, doi:10.1175/bams-84-3-357

- ^ Webber, p.104

- ^ Mikesh, pp.58–61

- ^ "Warrior Clans from the Bloody History of the Japanese Samurai". September 16, 2017.

- ^ "Igakusya tachi no sosiki hannzai kannto-gun 731 butai", Keiichi Tsuneishi

- ^ "Showa no Shunkan mou hitotsu no seidan", Kazutoshi Hando,1988

- ^ Mikesh, pp. 16–17, 22–23

- ^ Mikesh, pp.1,21&24

- ^ Mikesh, pp.7&25

- ^ Schindler, Hal (May 5, 1995). "Utah Was Spared Damage By Japan's Floating Weapons". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Crump, Jennifer (2010). Canada Under Attack. Chapter 12: Dundurn Press Ltd. pp. 167–177. ISBN 978-1-55488-731-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ McPhee, John (February 9, 2009). "Checkpoints". the New Yorker. pp. 56–63.

- ^ Mikesh, p.29

- ^ Karns, Jameson (March 2017). "A Fire Management Assessment of Fugo". Fire Management Today. 57: 53–57.

- ^ rcaf.com, 2010, "Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawks of the RCAF". Access date: March 3, 2011.

- ^ History of the Plutonium Production Facilities at the Hanford Site Historic District, 1943–1990 Retrieved April 27, 2007 Archived November 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Powles, James (February 2003), "Silent Destruction: Japanese Balloon Bombs", World War II, vol. volume 17 issue 6, p. 68

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d John McPhee. 1997. The Gravel Page. In Irons in the Fire, Noonday Press: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. pp 102-121.

- ^ a b Rogers, David. "How Geologists Unraveled the Mystery of Japanese Vengeance Balloon Bombs in World War II". Missouri University of Science & Technology. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- ^ AW Hathaway. 1993. Biography of Charles Butler Hunt, Geologist. Bulletin of the Association of Engineering Geologists, v30, #2, p 145. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aegweb.org/resource/resmgr/Legendary_People/Hunt.pdf

- ^ "Mysterious Balloon Found In Montana Mountain Area - Huge Paper Bag Bearing Jap Characters, Incendiary Device Studied By Military". The San Bernardino Daily Sun. Vol. 51. San Bernardino, California. December 19, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ Tanglen, Larry (2002). "Terror: Floated over Montana: Japanese World War II Balloon Bombs, 1944-1945". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 52 (4): 77. JSTOR 4520467.

- ^ a b Smith, Jeffery Alan (1999). War & Press Freedom: The Problem of Prerogative Power –. Language Arts & Disciplines.

- ^ "Balloon Bombs". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- ^ Tuttle, William M. (1995). "Daddy's Gone to War": The Second World War in the Lives of America's Children. p. 10. ISBN 978-0195096491. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ Kravets, David (May 5, 2010). "May 5, 1945: Japanese Balloon Bomb Kills 6 in Oregon". Wired.com. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Sol, Ilana (2008). On Paper Wings. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ *Peebles, Curtis (1991). The Moby Dick Project. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1-56098-025-4.

- ^ Moore, Wayne (October 10, 2014). "Bomb blown to "smithereens"". Castanet.net. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ "Japanese Balloon bomb - Picture of Canadian War Museum, Ottawa - TripAdvisor". www.tripadvisor.ca.

References

- The Fire Balloons from Greg Goebel's AIR VECTORS

- Anna Farahmand and Michael Webber, "Anti-aircraft mine & Intercontinental launching balloon bombs through jet stream" 2012

- Robert C. Mikesh, Japan's World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1973.

- "The Great Japanese Balloon Offensive" by MSgt. Cornelius W. Conley, USAF, Air University Review, Vol. XIX, No. 2 (January–February 1968): 68–83. [1]

- "Balloons Of War" by John McPhee, The New Yorker, January 29, 1996, 52–60.

- "Japan At War: An Oral History" by Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, New Press; Reprint edition (October 1993). Includes a personal account by a Japanese woman who worked in one of the fire balloon factories.

- Hall Schindler, "Utah Was Spared Damage By Japan's Floating Weapons," The Salt Lake Tribune, 1995-05-05. Accessed 2015-02-07.

- Webber, Bert (1975). Retaliation: Japanese attacks and Allied Countermeasures on the Pacific Coast in World War II. Oregon State University. ISBN 978-0-87071-076-6.

- "Silent Destructions: Japanese Balloon Bombs" by James M Powles, World War II, February 2003, Vol. 17 Issue 6 pg 64–70.

- "One Small Moment" by Lisa Murphy, American History, June 1995, Vol. 30 Issue 2 pg 66–72.

- Ross Coen, Fu-go:The Curious History of Japan's Balloon Bomb Attack on America, University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

- Jameson Karns, A Fire Management Perspective of FuGo, United States Forest Service, Fire Management Today, Vol.75 Issue 1, 2017.