Timpanogos: Difference between revisions

m Task 16: replaced (2×) / removed (0×) deprecated |dead-url= and |deadurl= with |url-status=; |

|||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

=={{anchor|European and United States contacts}}European and American contacts== |

=={{anchor|European and United States contacts}}European and American contacts== |

||

The first known Europeans to enter this area were a [[Kingdom of Spain|Spanish]] expedition of [[Franciscan]] missionaries led by Father [[Silvestre Vélez de Escalante]]. The [[Dominguez–Escalante Expedition]] of 1776 was trying to find a land route from [[Santa Fe, New Mexico]] to [[Monterey, California]]. Two or three Timpanogos from the [[Utah Valley]] were guides for the party. On September 23, 1776, they traveled down Spanish Fork Canyon and entered the Utah Valley.<ref>{{Citation | url=http://historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/trappers,_traders,_and_explorers/dominguez-escalanteexpedition.html | title=Dominguez-Escalante Expedition | work=Utah History to Go | publisher=Utah State Historical Society | accessdate=March 27, 2010}}</ref> Escalante documented the expedition in his journal, describing the people who lived around Utah Lake: |

The first known Europeans to enter this area were a [[Kingdom of Spain|Spanish]] expedition of [[Franciscan]] missionaries led by Father [[Silvestre Vélez de Escalante]]. The [[Dominguez–Escalante Expedition]] of 1776 was trying to find a land route from [[Santa Fe, New Mexico]] to [[Monterey, California]]. Two or three Timpanogos from the [[Utah Valley]] were guides for the party. On September 23, 1776, they traveled down Spanish Fork Canyon and entered the Utah Valley.<ref>{{Citation | url=http://historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/trappers,_traders,_and_explorers/dominguez-escalanteexpedition.html | title=Dominguez-Escalante Expedition | work=Utah History to Go | publisher=Utah State Historical Society | accessdate=March 27, 2010}}</ref> Escalante documented the expedition in his journal, describing the people who lived around Utah Lake: |

||

<blockquote>Round about it are these Indians, who live on the abundant fish of the lake, for which reason the Yutas Sabuaganas call them Come Pescados [FishEaters]. Besides this, they gather in the plain grass seeds from which they make atole, which they supplement by hunting hares, rabbits, and fowl of which there is great abundance here.<ref>{{Citation | url=http://www.mith2.umd.edu/eada/gateway/diario/diary.html#september25 | title=Derrotero y Diario | work=Early Americas digital archive | publisher=Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities | accessdate=March 27, 2010 | |

<blockquote>Round about it are these Indians, who live on the abundant fish of the lake, for which reason the Yutas Sabuaganas call them Come Pescados [FishEaters]. Besides this, they gather in the plain grass seeds from which they make atole, which they supplement by hunting hares, rabbits, and fowl of which there is great abundance here.<ref>{{Citation | url=http://www.mith2.umd.edu/eada/gateway/diario/diary.html#september25 | title=Derrotero y Diario | work=Early Americas digital archive | publisher=Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities | accessdate=March 27, 2010 | url-status=dead | archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110928071254/http://www.mith2.umd.edu/eada/gateway/diario/diary.html#september25 | archivedate=September 28, 2011 }}</ref></blockquote> |

||

The explorers named many geographic features in central Utah for the Timpanog tribe, who were then led by Turunianchi. The next recorded European visitor was [[Étienne Provost]], a French-Canadian trapper who visited the Timpanog in October 1824;<ref>{{Harvnb|Journal_of_W.A._Ferris|1941|pp=105–106}}</ref> the city of Provo and the Provo River are named after him. In 1826, American [[mountain man]] [[Jedediah Smith]] visited a camp along the [[Spanish Fork River]] with 35 lodges and about 175 people.<ref>{{Harvnb|Janetski|1991|pp=34–36}}</ref> |

The explorers named many geographic features in central Utah for the Timpanog tribe, who were then led by Turunianchi. The next recorded European visitor was [[Étienne Provost]], a French-Canadian trapper who visited the Timpanog in October 1824;<ref>{{Harvnb|Journal_of_W.A._Ferris|1941|pp=105–106}}</ref> the city of Provo and the Provo River are named after him. In 1826, American [[mountain man]] [[Jedediah Smith]] visited a camp along the [[Spanish Fork River]] with 35 lodges and about 175 people.<ref>{{Harvnb|Janetski|1991|pp=34–36}}</ref> |

||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

According to a state of Utah historical website, |

According to a state of Utah historical website, |

||

<blockquote>In 1861, President Abraham Lincoln signed an executive order establishing the original [[Uintah Reservation|Uintah Valley Reservation]] in the eastern part of the Utah territory ... Congress ratified the order in 1864 ... A council of the Ute people was called at Spanish Fork Reservation on 6 June 1865. The aged leader Chief Sowiette (a brother of [[Walkara|Chief Walkara]], who had died 10 years before) explained that the Ute people did not want to sell their land and go away, asking why the groups couldn't live on the land together. Chief Sanpitch (another brother of Walkara) also spoke against the treaty. However, advised by [[Brigham Young]] that these were the best terms they could get, the leaders signed. The treaty provided that the Utes give up their lands in central Utah, including the Corn Creek, Spanish Fork, and San Pete Reservations. Only the Uintah Valley Reservation remained. They were to move into it within one year, and be paid $25,000 a year for ten years, $20,000 for the next twenty years, and $15,000 for the last thirty years. (This was payment of about 62.5 cents per acre for all land in Utah and Sanpete counties.) However, Congress did not ratify the treaty; therefore, the government did not pay the promised annuity. Nevertheless, in succeeding years most of the Utah Ute people were removed to the Uintah Reservation.<ref>{{cite web|title=Treaty of the Uintah Reservation, 6 June 1855 |url=http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter5.html|website=Utah History To Go|accessdate=January 28, 2017|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109224647/http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter5.html|archivedate=January 9, 2017| |

<blockquote>In 1861, President Abraham Lincoln signed an executive order establishing the original [[Uintah Reservation|Uintah Valley Reservation]] in the eastern part of the Utah territory ... Congress ratified the order in 1864 ... A council of the Ute people was called at Spanish Fork Reservation on 6 June 1865. The aged leader Chief Sowiette (a brother of [[Walkara|Chief Walkara]], who had died 10 years before) explained that the Ute people did not want to sell their land and go away, asking why the groups couldn't live on the land together. Chief Sanpitch (another brother of Walkara) also spoke against the treaty. However, advised by [[Brigham Young]] that these were the best terms they could get, the leaders signed. The treaty provided that the Utes give up their lands in central Utah, including the Corn Creek, Spanish Fork, and San Pete Reservations. Only the Uintah Valley Reservation remained. They were to move into it within one year, and be paid $25,000 a year for ten years, $20,000 for the next twenty years, and $15,000 for the last thirty years. (This was payment of about 62.5 cents per acre for all land in Utah and Sanpete counties.) However, Congress did not ratify the treaty; therefore, the government did not pay the promised annuity. Nevertheless, in succeeding years most of the Utah Ute people were removed to the Uintah Reservation.<ref>{{cite web|title=Treaty of the Uintah Reservation, 6 June 1855 |url=http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter5.html|website=Utah History To Go|accessdate=January 28, 2017|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109224647/http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter5.html|archivedate=January 9, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

</blockquote> |

</blockquote> |

||

Revision as of 14:36, 28 September 2019

The Timpanogos (Timpanog, Utahs or Utah Indians) were a tribe of Native Americans who inhabited a large part of central Utah—particularly, the area from Utah Lake eastward to the Uinta Mountains and south into present-day Sanpete County. In some accounts they were called the Timpiavat,[1] Timpanogot, Timpanogotzi, Timpannah, Tempenny and other names.[2] During the mid-19th century, when Mormon pioneers entered the territory, the Timpanogos were one of the principal tribes in Utah based on population, area occupied and influence. Scholars have had difficulty identifying (or classifying) their language; most communication was carried out in Spanish or English, and many of their leaders spoke several native dialects of the Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family.

The Timpanogos have generally been classified as Ute people. They may have been a Shoshone band, since other Shoshone bands occupied parts of Utah. Nineteenth-century historian Hubert Howe Bancroft wrote in 1882 that the Timpanogos were one of four sub-bands of the Shoshone.[3]

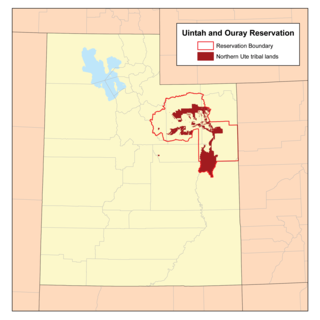

Chief Walkara, also known as Chief Walker, was a noted mid-19th-century chief[4] who led his people against Mormon settlers in the Walker War. The Shoshone and Ute shared a common genetic, cultural and linguistic heritage as part of the Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Most Timpanogos live on the Uintah Valley Reservation, established by executive order in 1861 and affirmed by congressional legislation in 1864, where they are counted with the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation.

In 2002, the Timpanogos won a federal case against the state in the Court of Appeals upholding their traditional rights to hunt, fish and gather on the reservation. The court concluded that their relationship with the federal government was well-established, although they are not listed by the Department of the Interior as a federally-recognized tribe. They have submitted an application and documentation to the Department of the Interior seeking federal recognition as an independent tribe.

Pre-European history

The Timpanogos probably entered Utah as part of the southern Numic expansion around 1000 CE (including the Ute) or in the subsequent central Numic Shoshonean expansion north and west from their Numic homelands in the Sierra Nevada. They were hunter-gatherers, living mostly on fish and wild game caught by the men and cooked and processed by the women and on the seeds and roots of wild plants gathered and prepared by the women.

As part of their religion, in the mornings they gathered together and greeted the morning with song to express gratitude to the Creator. They were divided into clans, each with its headman, spiritual leader and warrior. The clans would band together for specific purposes, such as hunting. There was no division of the land, and people were free to travel to different villages. They developed an extensive trading network.[5]

The Timpanogos lived in the Wasatch Range around Mount Timpanogos (named after them), along the southern and eastern shores of Utah Lake of the Utah Valley and in Heber Valley, Uinta Basin and Sanpete Valley. The band around Utah Lake became dominant due to the area's food supply.[6]

During the spring spawning season at Utah Lake, the tribes hosted an annual fish festival. Timpanogos, Ute and Shoshone bands would come from 200 miles (320 km) away to gather fish.[7] At the festival there was dancing, singing, trading, horse races, gambling and feasting. It was an opportunity for young people to find a mate from another clan, since exogamous marriage (outside their clan) was required.[5] The shores of Utah Lake became a sacred meeting place for the Timpanogos, Ute and Shoshone tribes.[8]

European and American contacts

The first known Europeans to enter this area were a Spanish expedition of Franciscan missionaries led by Father Silvestre Vélez de Escalante. The Dominguez–Escalante Expedition of 1776 was trying to find a land route from Santa Fe, New Mexico to Monterey, California. Two or three Timpanogos from the Utah Valley were guides for the party. On September 23, 1776, they traveled down Spanish Fork Canyon and entered the Utah Valley.[9] Escalante documented the expedition in his journal, describing the people who lived around Utah Lake:

Round about it are these Indians, who live on the abundant fish of the lake, for which reason the Yutas Sabuaganas call them Come Pescados [FishEaters]. Besides this, they gather in the plain grass seeds from which they make atole, which they supplement by hunting hares, rabbits, and fowl of which there is great abundance here.[10]

The explorers named many geographic features in central Utah for the Timpanog tribe, who were then led by Turunianchi. The next recorded European visitor was Étienne Provost, a French-Canadian trapper who visited the Timpanog in October 1824;[11] the city of Provo and the Provo River are named after him. In 1826, American mountain man Jedediah Smith visited a camp along the Spanish Fork River with 35 lodges and about 175 people.[12]

Conflicts with the Mormons

By the time Mormon pioneers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, the Timpanogos were guided by Turunianchi's grandson, Walkara. Walkara led the tribe with a number of sub-chiefs, most of whom were his brothers: Chief Arapeen, Chief San-Pitch, Chief Kanosh, Chief Sowiette, Chief Tabby-To-Kwanah, Chief Grospean and Chief Amman. Brigham Young once called them a "royal line" of Indian chiefs, and they had hereditary leadership through their clan. Parley P. Pratt explored the Utah Valley and Utah Lake.[13]

Battle Creek massacre

The first battle between settlers and Indians, known by the Americans as the Battle Creek massacre, occurred in early March 1849 at present-day Pleasant Grove, Utah. A company of 40 Mormon men went to the Utah Valley to persuade the Timpanogos to stop stealing cattle from the Salt Lake Valley; both peoples were competing for resources. Brigham Young ordered the Mormons "to take such measures as would put a final end to their depredations in future".[14][15] The company went to the village of Little Chief, who told them where the men who had stolen cattle were. The Mormons attacked the village, killing four Timpanogos. They took women and children as captives, including Nuch (who, as Black Hawk, later led the Black Hawk War).[7]

Battle at Fort Utah

On March 10, 1849 Brigham Young ordered 30 families to colonize Utah Valley, with John S. Higbee president and Dimick B. Huntington and Isaac Higbee counselors.[7] The group of about 150 people headed for Timpanogos territory, and the Timpanogos viewed this as an invasion of their territory and sacred land.[16] As the colonizers entered the valley, they were blocked by a group of Timpanogos led by An-kar-tewets and warned that trespassers would be killed.[17] Huntington raised his hand and swore by the sun god that they would not try to drive the Timpanogos off their lands or take away their rights. The Timpanogos let them enter[7][17]

The settlers built a stockade, Fort Utah, arming it with a twelve-pound cannon.[18] They built several log houses, surrounded by a 14-foot (4.3 m) palisade 20 by 40 rods long (330 by 660 feet [100 by 200 m]) with gates at the east and west ends and a middle deck for the cannon. The fort, built on the sacred grounds of the annual fish festival, was very close to the main Timpanogos village on the Provo River. The settlers fenced off pastures, and their cattle ate (or trampled) the seeds and berries which were an important part of the Timpanogos' diet. By fishing with gill nets they took more than they needed, leaving an insufficient amount for the Timpanogos. With their traditional food sources gone, the Timpanogos starved.[8][19][20] The settlers also brought measles, endemic to them but an unfamiliar infectious disease to the Timpanogos. Lacking acquired immunity, the natives experienced epidemics with high mortality rates which disrupted their society. They asked the settlers for medicine to fight the new disease.[8]

In August a Timpanogo, Old Bishop, was murdered by Rufus Stoddard, Richard Ivie, and Gerome Zabrisky for his shirt.[8][18][21] The angry Timpanogos demanded that the murderers be handed over to them, but the settlers refused. Some Timpanogos shot at trespassing cattle or stole corn in retaliation. The winter was hard, and the Timpanogos stole cattle to survive.

By January 1850, the settlers at Fort Utah reported the increasing tension to officials in Salt Lake City and requested a military party to attack the Timpanogos. A militia from Salt Lake City engaged the Timpanogos in battle on February 8 and 11. On February 14 eleven Timpanogo warriors surrendered, but the militia executed them in front of their families and a government surgeon beheaded them after death for research. The militia lost one man and killed 102 Timpanogos.[22]

Walker and Black Hawk Wars

By the time of the Walker War, named for Chief Walkara, the Timpanogos numbered only about 1,200. The war included several armed conflicts with settlers and Mormon militiamen.

Chief Black Hawk, leader of the Black Hawk War, was a son of San-Pitch.[4] The war was more extensive, with additional deaths on both sides.

Uintah Reservation

According to a state of Utah historical website,

In 1861, President Abraham Lincoln signed an executive order establishing the original Uintah Valley Reservation in the eastern part of the Utah territory ... Congress ratified the order in 1864 ... A council of the Ute people was called at Spanish Fork Reservation on 6 June 1865. The aged leader Chief Sowiette (a brother of Chief Walkara, who had died 10 years before) explained that the Ute people did not want to sell their land and go away, asking why the groups couldn't live on the land together. Chief Sanpitch (another brother of Walkara) also spoke against the treaty. However, advised by Brigham Young that these were the best terms they could get, the leaders signed. The treaty provided that the Utes give up their lands in central Utah, including the Corn Creek, Spanish Fork, and San Pete Reservations. Only the Uintah Valley Reservation remained. They were to move into it within one year, and be paid $25,000 a year for ten years, $20,000 for the next twenty years, and $15,000 for the last thirty years. (This was payment of about 62.5 cents per acre for all land in Utah and Sanpete counties.) However, Congress did not ratify the treaty; therefore, the government did not pay the promised annuity. Nevertheless, in succeeding years most of the Utah Ute people were removed to the Uintah Reservation.[23]

By 1872 all the Timpanogos had moved to the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation, but some occasionally returned to fish on Utah Lake into the 1920s.[24][25]

Population estimates

In 1847, at the time of the Mormon pioneers' arrival, the Timpanogo population has been estimated at about 70,000; their numbers had been dwindling because of competing bands of Shoshone raiders since the early 19th century. Many died from smallpox and other infectious diseases introduced by American settlers, and an early-1850s measles epidemic was particularly devastating. Many Native American tribes had their numbers reduced by more than 90 percent as a result of disease introduced by Europeans.

The number of Timpanogos may have been less. "The exact number of all the Indians who lived in Utah Territory is unknown. An 1861 report from J. F. Collins, Utah superintendent of Indian affairs, said that no one had ever 'been able to obtain satisfactory information in regard to their numbers'. Collins estimated ... that there may have been fifteen to twenty thousand Indians (of all tribes) in Utah prior to the arrival of the first Mormon settlers" in 1847.[26]

Indian Superintendent Forney's 1859 annual report to the federal commissioner of Indian affairs provided estimates of tribal numbers:

- Shoshones or Snakes – 4,500 (This did not include the Timpanogos; other Shoshone lived in northern and western Utah.)

- Bannocks – 500

- Uinta Utes – 1,000

- Spanish Fork and San Pete Farms – 900 (farms and reservations; those on farms were Timpanogos.)

- Pahvant (Utes) – 700

- Paiutes (South) – 2,200

- Paiutes (West) – 6,000

- Elk Mountain Utes – 2,000

- Honey Lake Washo – 700

This gives a total of 18,500 Native Americans estimated to live in Utah in 1859, listing all tribes and bands by names commonly used at the time.[27]

Historical confusion

The Timpanogos may have been a Shoshone band who were part of the Central Numic people or a branch of the Southern Numic people, which includes the Ute. During the pioneer era, they were often called the Utah Indians (sometimes confused with the Ute Indians). At the time, most Ute were from Colorado and farther east in Utah.

Three major groups of Ute Indian bands were placed by the federal government in the Uinta Valley Reservation during the 1880s.[28] Afterward, the Utah Indians (or Timpanogos) became conflated with—and were often considered to have merged with—the Ute Indians in historical documents.

Although many historians refer to Sowiette, San-Pitch and their people as Utes, at the time of the Uinta treaty they were known as the Utah Indians or Timpanogos. According to some of their descendants, they became known as the Ute only after moving to the Uintah Reservation and joining other Ute there.[28][29] The Timpanogos are not usually listed as a current (or former) Shoshone band.

In Timpanogos Tribe vs Conway, (2002), U.S. Appeals Court Judge Tena Campbell ruled: "Plaintiff asks the court to make unreasonable inferences and leap to the conclusion that because Mr. Montes and his ancestors are not Ute, the (Timpanogos Tribe), whose members include Mr. Montes, is a Shoshone tribe in existence since aboriginal times and for whom the reservation was set aside. The court will not make that leap, nor will it allow a jury to do so."[30] Judge Campbell ruled that President Abraham Lincoln did not establish the Uintah Valley Reserve; it was not officially established until its authorization by Congress in 1864. Lincoln signed an executive order creating the Uintah Valley Reservation dated October 3, 1861.[contradictory]

According to the September 6, 1858 Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Utah Superintendency, the Utah (Timpanogos) appear to have been considered separate from the Snake Indians and the other Shoshone:

The tribes and fragments of tribes with whom I had business relations ... are as follows, to wit: on the second day of December last I was visited by San-Pitch, a principal chief of the Utahs, and a few of his men ...

On the 10th of December following, Little Soldier, chief, and Benjamin Simons, sub-chief, of a band of Sho-sho-nes, with some of their principal men, called on me ... The territory claimed by them includes Salt lake, Bear river, Weber river and Cache valley ...

About the 22nd day of December last, I was visited at Camp Scott, by White-eye and San-Pitch, Utah chiefs, with several of their bands ... These Indians belong to one of the principal tribes of this Territory. There is but one other large tribe (the Snakes), as I am informed.

The best land belonging to the Utahs is situated in Utah valley ... Much has been done and is doing for this tribe, (the Utahs) ... Strenuous efforts will be made to induce this tribe (the Utahs) to locate permanently ...

I visited San-Pete creek farm [reservation] last month, (August,) which is situated in the west end of San-Pete valley and county. This farm was opened about two years ago, under the directions of Agent Hurt, for a band of the Utahs under Chief Arapeen, a brother of San-Pitch ...

I have heretofore spoken of a large tribe of Indians known as the Snakes. They claim a large tract of country lying in the eastern part of this Territory, but are scarcely ever found upon their own land. They generally inhabit the Wind river country, in Oregon and Nebraska Territories and they sometimes range as far east as Fort Laramie ... This tribe numbers about twelve hundred souls, all under one principal chief, Wash-a-kee. He has perfect command over them, and is one of the finest looking and most intellectual Indians I ever saw ...

For several years, an enmity has existed between the Utahs and the Snakes ... Accordingly, on the 13th of May, Wash-a-kee, of the Snakes, White-Eye, Son-a-at, and San-Pitch, of the Utahs, with the sub-chiefs of the different tribes, and also several chiefs of the Ban-acks, assembled in council at Camp Scott, when, after considerable talk and smoking, peace was made between the two tribes."[31]

Uncertain legal status

The Timpanogos relocated to the Uintah Valley Reservation. In court cases, they have been classified as part of the Ute Indian Tribe and outside it. Although most Timpanogos live on the reservation and continue their culture, many are of mixed race with less than one-half Native American blood; this determines which federal programs (such as education) they may qualify for. During the 1950s, the federal government stopped recognizing most mixed-blood Ute as part of its Indian termination policy.

The Ute tribe consists of bands of Uintah, White River and Uncompahgre Ute people who were forced to relocate to Utah by the Congressional Act of 1880. They gradually intermarried, and some differences between bands lessened. Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal), the Ute bands organized as a unified tribe with a constitution based on the election of a chief and council. Their documents did not mention the Timpanogos, who believe that the 1950s federal termination of Native American status of the Ute tribe's mixed-blood members should have had no effect on themselves[32][33]

In 2000 the Timpanogos sued the state of Utah in Timpanogos Tribe v. Conway, seeking continued rights for their members for hunting, fishing and gathering on the Uintah Valley Reservation within the boundaries established by the case known as Ute V (Ute Tribe v. Utah, 1997). They sought an injunction against state prosecution within the reservation and acknowledgement by the state as the "Indians of Utah" referred to in the 1861 executive order and 1864 act of Congress establishing the reservation. The Ute Indian Tribe filed with the state against the Timpanogos, arguing that the latter were part of the Ute Tribe and not independent.

The issues were narrowed on appeal. Judge Tena Campbell concluded in Timpanogos v. Conway (2002) that the Timpanogos Tribe merged with the Ute Indian Tribe in 1865, ruling that the members had rights for hunting, fishing and gathering on the reservation.[34][35] Because of the conflicting judicial rulings, the Timpanogos have applied to the Department of Interior for independent federal recognition and a clarification of their current rights and status.

Notable Timpanogos

- Chief Turunianchi, principal Indian chief in central Utah during the late 18th century (at the time of the 1776 Dominguez-Escalante Expedition

- Chief Walkara, also called Chief Walker: Most prominent chief in the Utah area when the Mormon pioneers arrived; leader during the Walker War

- Sanpitch, chief of the San Pitch tribe. A brother of Chief Walkara; Sanpete County is named for him.

- Black Hawk, son of Chief Sanpitch; leader during the Utah Black Hawk War

- Chief Arapeen, for whom the Arapeen Valley is named

- Chief Kanosh, for whom the town of Kanosh, Utah is named

- Chief Sowiett

- Chief Tabby-To-Kwanah

- Chief Grospean

- Chief Amman

Legacy

- Mount Timpanogos, a mountain in Utah

- Timpanogos Cave National Monument, a cave system near Mount Timpanogos

- Timpanogos High School in Orem, Utah

- Mount Timpanogos Utah Temple, an LDS temple

References

- ^ Handbook of American Indians V2 North of. Books.google.com.

- ^ Janetski 1991, p. 32

- ^ The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. 1882. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ a b Our Timpanogos Ancestors

- ^ a b History of the Timpanogos Tribe

- ^ Cuch 2000, p. 177

- ^ a b c d The Utah Gold Rush: The Lost Rhoades Mine and the Hathenbruck Legacy. p. 104.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d "Fort Utah and Battle Creek 1849–50". Black Hawk Productions.

- ^ "Dominguez-Escalante Expedition", Utah History to Go, Utah State Historical Society, retrieved March 27, 2010

- ^ "Derrotero y Diario", Early Americas digital archive, Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, archived from the original on September 28, 2011, retrieved March 27, 2010

- ^ Journal_of_W.A._Ferris 1941, pp. 105–106

- ^ Janetski 1991, pp. 34–36

- ^ Jensen 1924, p. 31

- ^ "0pen Hand and Mailed Fist: Mormon-Indian Relations in Utah, 1847–52" by Howard A. Christy, Utah Historical Quarterly Volume XLVI

- ^ Hose a Stout Diary, 8 vols., 4:48, typescript, Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. A renegade band of Ute Indians had raided herds and taken stock from Tooele Valley and southern Great Salt Lake Valley; the men had earlier declared their opposition to the white settlers. The band was led by three brothers, "Roman Nose," "Blueshirt," and possibly "Cone". Reportedly their chief had driven them out of Utah Valley because they refused to stop stealing cattle from the Mormons. See Oliver B. Huntington Diary, pp. 52–53, Lee Library.

- ^ "The History of Utah American Indians: Chapter Five – The Northern Utes of Utah".

- ^ a b Jared Farmer. On Zion's <Munt: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape.

- ^ a b Farmer 2008, pp. 64–65

- ^ Elder Marlin K. Jensen. "The Rest of the Story: Latter-day Saint Relations with Utah's Native Americans" (PDF).

- ^ "Mormons and Native Americans historical Overview".

- ^ "Murdered Ute's Ghost Haunts Utah History", Salt Lake Tribune, November 5, 2000, retrieved April 10, 2010

- ^ Farmer 2008, pp. 70–76

- ^ "Treaty of the Uintah Reservation, 6 June 1855". Utah History To Go. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Holzapfel 1999, p. 41

- ^ "The Timpanogos Nation: Uinta Valley Reservation". www.timpanogostribe.com. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Collins, JF (1861), A Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, p. 21, p. 125

- ^ Bowman, George W. (1859), Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Accompanying the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior for the Year 1859 (Washington, DC), p. 365

- ^ a b "Timpanogos Tribe".

- ^ "Treaty of the Uintah Reservation 6 June 1855".

- ^ "Judge Rejects Motion Granting Tribe Special Rights".

- ^ Forney, Jacob (September 6, 1858), Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Utah Superintendency, September 6, 1858, by Jacob Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, W.T., pp. 209–213

- ^ Note: This is in contrast with the Ute position in Ute Tribe v. Utah 773 F.2d 1087, 1093 (10th Cir. 1985) (en banc), what the parties called Ute III.

- ^ [https://www.ca10.uscourts.gov/opinions/14/14-4028.pdf Ute Indian Tribe v. State of Utah, et al., (D.C. Nos. 2:75-CV-00408-BSJ and 2:13-CV-01070-DB-DBP), Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals (2015). Note: The 1985 case had reaffirmed the boundaries of three areas of Ute reservation lands against the state challenge. The US Supreme Court declined to hear this case. But, the state continued to prosecute Ute persons on what was tribal reservation land and got a separate case to the state Supreme Court and the US Supreme Court.

In Hagen v. Utah (1994), 510 U.S. 399, 421–22, the US Supreme Court agreed with the state that a portion of Uintah Reservation had been reduced by Congressional action since 1985. When the state began again to prosecute Ute within the reservation in state courts for offenses, the Appeals Court brought the case back in 1997 to reconcile the boundaries of the different cases, calling it Ute V. The 10th Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that the boundary issue was resolved.

Afterward, the state began again to prosecute Ute for offenses in Indian country, apparently to challenge the court ruling. In 2015 the Appeals Court heard testimony from the Ute Indian Tribe plaintiffs and ruled that this disruptive behavior by the state and county officials had to stop, saying that the issues had been settled for nearly 20 years.

And the case for finality here is overwhelming. The defendants may fervently believe that Ute V drew the wrong boundaries, but that case was resolved nearly twenty years ago, the Supreme Court declined to disturb its judgment, and the time has long since come for the parties to accept it.

- ^ "Timpanog Name".

- ^ Note: Historically the several bands of Utes had lived independently in the territory of Colorado and Eastern Utah. But their relocation by an act of Congress to the existing Uintah Valley Reservation in the 1880s had the legal effect of a treaty recognizing them as a tribe, as noted by the courts.