User:Kmubeen/Swahili coast: Difference between revisions

Edited religion |

|||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

The primary religion of the Swahili coast is [[Islam]].<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":13" /> Initially, unorthodox [[Muslims]] fleeing persecution in their homelands may have settled in the region, but it is likely that the region took hold through Arab traders.<ref name=":9" /> The majority of Muslims on the Swahili coast are [[Sunni Islam|Sunni]], but many people continue non-Islamic traditions.<ref name=":9" /> For example, spirits who bring illness and misfortune are appeased and people are buried with valuable items. In addition, teachers of Islam are allowed to become medicine men; having medicine men being a practice carried over from local tribal religions.<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":13" /> Men wear protective [[Amulet|amulets]] with [[Quran]] verses.<ref name=":13" /> The historian P. Curtis said about Islam and the Swahili coast, "The Muslim religion ultimately became one of the central elements of Swahili identity."<ref name=":9" /> |

The primary religion of the Swahili coast is [[Islam]].<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":13" /> Initially, unorthodox [[Muslims]] fleeing persecution in their homelands may have settled in the region, but it is likely that the region took hold through Arab traders.<ref name=":9" /> The majority of Muslims on the Swahili coast are [[Sunni Islam|Sunni]], but many people continue non-Islamic traditions.<ref name=":9" /> For example, spirits who bring illness and misfortune are appeased and people are buried with valuable items. In addition, teachers of Islam are allowed to become medicine men; having medicine men being a practice carried over from local tribal religions.<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":13" /> Men wear protective [[Amulet|amulets]] with [[Quran]] verses.<ref name=":13" /> The historian P. Curtis said about Islam and the Swahili coast, "The Muslim religion ultimately became one of the central elements of Swahili identity."<ref name=":9" /> |

||

<br /> |

|||

=== Architecture === |

=== Architecture === |

||

Often lived in houses built with coral blocks. Earliest known mosques, built of wood, are at Tanga, Kenya and date to the 9th century CE.<ref name=":9" /> |

Often lived in houses built with coral blocks. Earliest known mosques, built of wood, are at Tanga, Kenya and date to the 9th century CE.<ref name=":9" /> |

||

Revision as of 02:02, 14 November 2019

Swahili coast | |

|---|---|

| |

| Countries | Kenya Tanzania Mozambique Somalia Comoros |

| Major Cities | Dar es Salaam (Mzizima) Malindi Mombasa Sofala |

| Ethnic groups | |

| • Bantu | Swahili |

The Swahili coast is a coastal area of the Indian Ocean in Southeast Africa inhabited by the Swahili people. It mainly consists of Kenya, Tanzania, and northern Mozambique as well as southern Somalia. In addition, several coastal islands are included in the Swahili coast such as Zanzibar and Comoros. Areas of what is today considered the Swahili coast were historically known as Azania or Zingion in the Greco-Roman era, and as Zanj or Zinj in Middle Eastern, Chinese and Indian literature from the 7th to the 14th century.[1][2] The word "Swahili" means people of the coast in Arabic and is derived from the word "sahil" (coast).[3] The Swahili people and their culture formed from a distinct mix of African and Arab origins.[3] The Swahilis were traders and merchants and readily absorbed influences from other cultures.[4] Historical documents including the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and works by Ibn Battuta describe the society, culture, and economy of the Swahili coast at various points in its history. The Swahili coast has a distinct culture, demography, religion and geography, and as a result - along with other factors, including economic - has witnessed rising secessionism.[5]

History

Early on, those living on the Swahili coast prospered because of agriculture helped by regular yearly rainfall and animal husbandry.[3] The shallow coast was important as it provided seafood.[3] Starting in the early 1st millennium CE, trade was crucial.[3][6] Submerged river estuaries created natural harbors as well as the yearly monsoon winds helped trade.[3][6] Later in the 1st millenium there was a huge migration of Bantu people.[3]

Indian Ocean Trade

The rise of the Swahili coast city-states can be largely attributed to the region's extensive participation in a trade network that spanned the Indian Ocean.[7][8] The Indian Ocean's trade network has been likened to that of the Silk Road, with many destinations being linked through trade. It has been noted that the Indian Ocean trade network actually connected more people than the Silk Road's.[6] The Swahili coast largely exported raw products like timber, ivory, animal skins, spices, and gold.[6] Finished products were imported from as far as east Asia such as silk and porcelain from China, spices and cotton from India, and black pepper from Sri Lanka.[9] Some of the other imports received from Asia and Europe include cottons, silks, woolens, glass and stone beads, metal wire, jewelry, sandalwood, cosmetics, fragrances, kohl, rice, spices, coffee, tea, other foods and flavorings, teak, iron and brass fittings, sailcloth, pottery, porcelain, silver, brass, glass, paper, paints, ink, carved wood, books, carved chests, arms, ammunition, gunpowder, swords and daggers, gold, silver, brass, bronze, religious specialists, and craftsmen.[7] Other places that traded with the Swahili coast include Egypt, Greece, Rome, Assyria, Sumeria, Phoenicia, Arabia, and Persia.[10] Trade in the region decreased during the Pax Mongolica due to overland trade being cheaper during that period, however, trade by ships provided the advantage that the goods that were transported on them were in bulk, meaning they could be available to the mass market.[6] Many different ethnic groups were involved in the Indian Ocean's trade network, however, especially in the western part of the Indian Ocean, Swahili coast being included, muslim merchants dominated the trade because they had the money to build ships.[6] The yearly monsoon winds carried ships from the Swahili coast to the eastern Indian Ocean and back. These yearly winds were the catalyst for trade in the region as they reduced the risk associated with sailing and made it predictable. The monsoon winds were less strong and reliable as one travelled further South along Africa's coast resulting in settlements being smaller and less frequent towards the South.[3] Trade was further encouraged by the invention of lateen sails which allowed merchants to travel apart from the monsoon winds.[6] Evidence for Indian Ocean trade includes the presence of pot sherds on coastal archaeological sites that can be traced back to China and India.[11]

Slave trade

It has been estimated that between 1500 and 1900 CE as many as 17 million people were sold into slavery from East and North Africa and the Middle East and transported by Muslim slave traders through the Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Sahara desert to distant locations.[12] However, these estimates have been contested citing that the total population of Africa during the period may have been about 40 million and the figures of the likes of 17 million people being transported were not likely during that time.[13] A series of slave uprisings took place between 869 and 883 CE in Basra, a city of present-day Iraq, referred to as the Zanj Rebellion. The enslaved Zanj were likely transported from the African Great Lakes area and more southern areas of East Africa.[14] The uprising grew to more than 500,000 slaves and free men as well, who were used in strenuous agriculture labor.[15] Although not all the slaves in the uprising were of African origin, the great majority were, and the 9th century Zanj revolts in Iraq is some of the best evidence of a large number of people being sold into slavery from Eastern Africa.[16]

Coins

On the Swahili coast, coin minting can be correlated to an increase in Indian Ocean trade.[17] The earliest coins share many similarities to coins from Sindh. Some estimate that coins were minted on the Swahili coast as early as the mid 9th century until the end of the 15th century CE.[17] The making of coins came comparatively late to this area with many other cultures starting to make coins several centuries earlier. There are archaeological records of foreign coins being used in the area but few coins of foreign origin have been excavated. Previously, it was believed that the coins from the Swahili coast were of Persian origin, but now it is recognized that these are in fact indigenous coins.[17] The coins found on the coast only have inscriptions in Arabic, not Swahili. The coins from this region can be put into five categories: Shanga silver, Tanzanian silver, Kilwa copper, Kilwa gold and Zanzibar copper. Silver is not found locally on the Swahili coast, so the metal had to be imported.[17]

Coastal Islands

There are many islands close to the Swahili coast including Zanzibar, Kilwa, Mafia and Lamu in addition to distant Comoros which is sometimes considered part of the Swahili coast. Several of these islands became very powerful through trade including Zanzibar and Kilwa. Before these islands became trade hubs, it is likely that the abundant local resources were very important to the islands' inhabitants. These resources include mangroves, fishing, and crustaceans.[18] Mangroves were important as they provided wood for boats. However, archaeological digs reveal that the culture of the Swahili people living on these islands was adapted to trade and their maritime surroundings quite early on.[18]

Kilwa

Although today Kilwa is in ruins, historically it was one of the most powerful city states on the Swahili coast.[4] One of the main exports along the Swahili coast was gold and in the 13th century the city of Kilwa took control of the gold trade from Banadir in modern-day Somalia.[19][20][21] By the mid-14th century the sultan of Kilwa was able to assert his power over several other city states. Kilwa levied a customs duty on the gold that was shipped north from Zimbabwe that stopped in Kilwa's port. In Kilwa's Husuni Kabwa, or Great Fort, there is evidence of gardens, a pool, and commercial activities. The fort served as a palace and area to store commercial goods and was built by sultan Al-Hasan Ibn Suleman.[4] The fort consists of a public courtyard, and a private area. Due to the intricate architecture present in Kilwa Ibn Battuta, a Moroccan explorer, described the town as "one of the most beautiful towns in the world."[3] Although Kilwa had been trading for centuries, the city's wealth and control of the gold trade attracted the Portuguese who were in search of gold. During the period of Portuguese subjugation, trade essentially stopped in Kilwa.[4] However, when the Omani overthrew the Portuguese from the area in the late 17th and early 18th century CE, the city experienced an economic resurgence. Kilwa later became the capital of German colonial East Africa.[4]

Zanzibar

Today, Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous region of Tanzania made up of the Zanzibar Archipelago. The archipelago is 25-50 kilometers (16-31 mi) from the mainland. Its main industries are tourism, spice production such as cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and black pepper, and raffia palm trees.[22] In 1698, Zanzibar became part of the Omani sultanate after sultan Saif bin Sultan defeated the portuguese at Mombasa. In 1832 the sultan of Oman moved his capital from Muscat to Stone Town, the main city of the Zanzibar archipelago.[23] He encouraged the creation of clove plantations as well as the settlement of Indian traders. Until 1890 the sultans of Zanzibar controlled part of the Swahili coast known as Zanj which included Mombasa and Dar es Salaam. At the end of the 19th century Great Britain and Germany subjugated Zanzibar. [24]

Culture

Fish and shellfish are common in the Swahili coast's food due to its proximity and reliance on the coast. [25] In addition, Coconuts and many different spices in addition to tropical fruits are often used. The Arabic influence can be seen in the small cups of coffee that are available in the area as well as the sweet meats that can be tasted. The Arab influence is also seen in the swahili language, architecture, and boat design in addition to food as aforementioned.[9]

Language

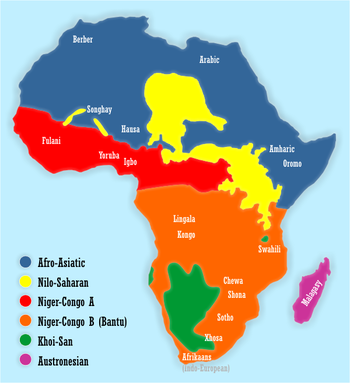

Swahili is the lingua franca of East Africa and the national language of Kenya and Tanzania in addition to being one of the languages of the African Union.[3][26] Estimates of the number of speakers vary greatly but estimates are usually around 50, 80 and 100 million people.[27] Swahili is a Bantu language with heavy influenced byArabic with the word "Swahili" itself descending from the Arabic word "sahil," meaning "coast"; "Swahili" meaning "people of the coast."[3][28] Some hold that Swahili is a completely Bantu language with only a few Arabic loanwords, however, it is more widely accepted that Bantu and Arabic mixed to form Swahili.[28] It has been hypothesized that the mixing of languages was facilitated by intermarriage between natives and Arabs in addition to general interactions.[28] Most likely, Swahili was around in some form before Arab contact but then was heavily influenced. Swahili syntax is very similar to that of other Bantu languages as, like other Bantu languages, Swahili has five vowels (a,e,i,o,u).[28]

Religion

The primary religion of the Swahili coast is Islam.[3][29] Initially, unorthodox Muslims fleeing persecution in their homelands may have settled in the region, but it is likely that the region took hold through Arab traders.[3] The majority of Muslims on the Swahili coast are Sunni, but many people continue non-Islamic traditions.[3] For example, spirits who bring illness and misfortune are appeased and people are buried with valuable items. In addition, teachers of Islam are allowed to become medicine men; having medicine men being a practice carried over from local tribal religions.[3][29] Men wear protective amulets with Quran verses.[29] The historian P. Curtis said about Islam and the Swahili coast, "The Muslim religion ultimately became one of the central elements of Swahili identity."[3]

Architecture

Often lived in houses built with coral blocks. Earliest known mosques, built of wood, are at Tanga, Kenya and date to the 9th century CE.[3]

Notes(Everything above this point is the draft)

A product of the multi-cultured environment of the Swahili coast was the development of the Swahili language, a fundamentally Bantu language that contains a number of Arabic [30] and Hindu [31] loanwords due to the significant trade with Arabia and India [32].

In order to take control of the gold trade the Portuguese attacked settlements on the Swahili coast[20], including Kilwa in 1505.[20] The city is in ruins to this day.

The kingdoms on the Swahili coast rose because of the trade networks in which they were involved, but they began to decline, possibly in part because of colonization by the Portuguese, [33] who were interested in controlling the trade markets on the Swahili coast.[33] Since the Portuguese took over the trade markets the kingdoms were not able to trade as much as before and as a result began to

Coins

Before, it was thought that the Swahili culture was implanted from Persia, but now it is more accepted that it is homegrown with influence. Minted and used own coins as early as mid 9th century up to 15th century. Coins came comparatively late to this area. Records of foreign coins but no excavations supporting early foreign coins. When started minting, however, coinage established in Indian Ocean. Did not adopt coinage. Not Shirazi, indigenous. However, swahili coastal population foreign as well as African. Not colonized by Arabs and Persians, but not isolated either. Coins are in Arabic not KiSwahili. Early Swahili Coast coins different from contemporary dirhams. Silver not local and needed to be imported. Long life of coin types, so hard to gain time-frame. Shange silver, Tanzanian-type silver, Kilwa copper, Zanzibar copper, Kilwa gold. Shanga 9th to 12th century. Tanzanian 10th-11th century. Kilwa copper 11th-14th century. Zanzibar 12-14th centuries. Silver coins found almost exclusively at Zanzibar and Pemba. Replaced by copper at Kilwa and/or Mafia. Some found in Australia. Minting of coins happened with an increase in Indian Ocean trade. Possibly, used to establish authority. Earliest coins similar to those of Sindh.[17]

Culture

The food of the region uses Coconuts, Fish, and many different spices in addition to tropical fruits. The arabic influence can be seen in the small cups of coffee that are available in the area as well as the sweet meats that can be tasted. The arab influence is also seen in the swahili language, architecture, and boat design in addition to food as aforementioned.[9] Fish and shellfish are common in this region's food due to its proximity and reliance on the coast. [25]

Religion

The primary religion is islam. The coastal peoples more devout than hinterland peoples. Belive in djins. Men wear protective amulets with quran verses. Divination is practiced. From local tribal religions, medicine people incorporated. Only teachers of islam allowed to become medicine men. [29]

Swahili Language

Swahili is a Bantu language with a lot of borrowed words from arabic and lingua franca of East Africa. Three theories: Swahili is an Arabic language, Swahili is a mixture of Arabic and Bantu languages, Swahili is completely a Bantu language. First theory supported by many arabic words and islam's prominence on the coast. Some think Swahili is mixed because of intermarriage. Others think that it is a result of general interaction. Most likely, Swahili was in existence before Arab contact, and then was heavily influenced. Swahili syntax is very similar to that of other Bantu languages. Like other Bantu languages, swahili has five vowels (a,e,i,o,u).[28]

Swahili pasted from Swahili language

Various estimates have been put forward and they vary widely, ranging from 15 million to 50 million.[27] Swahili is also one of the working languages of the African Union and officially recognised as a lingua franca of the East African Community.[26]

Offshore Islands

Lamu, Zanzibar, Kilwa and Mafia, distant Comoros. Monsoon winds helped support trade. Mangroves provide fishing mollusks crustaceans, wood for charcoal and building. Digs reveal earlier maritime adaptation rather than a later shift from hinterland to maritime. [18]

Kilwa

Today quite poor, but historically one of the most powerful city states. Swahili means people of the coast. Readily absorbed influences. They were traders, merchants. This is an Islamic culture. By the mid 14th century the sultan of Kilwa had asserted power over the other city states. Kilwa levied a customs duty on all the gold ship north from Zimbabwe. The Great Palace on Kilwa. Evidence of gardens, pool, and commercial activities. Built by sultan Al-Hasan Ibn Suleman. Consists of public area and private area. The Portuguese came in search of gold, and found it in Kilwa. Replaced by the Omanis. They had been trading for centuries. In the late 17th and 18th century, they launched an attempt to kick the portuguese out. Kilwa experienced an economic resurgence. Later became the capital of German colonial East Africa.[4]

Persian influence

It was accepted by writers such as Hollingsworth, Pearce, and Ingrams that before the large Arab influence, there were Persian "Shirazi" settlers. However, others have pointed out that the distinction between Persian and Arab architecture was not clear enough to say that early architecture on the Swahili coast is Persian as Persian architecture evolved from Arab architecture. Some evidence does exist for Persian settlement in the form of inscriptions with Persian names in Mogadishu from the 13th century. However, many consider the sum of evidence supporting early Persian settlement to be not much. When towns foreign name not Swahili, part of Swahili cosmopolitanism. [34]

Indian Ocean Trade

Indian ocean trade linked many places. Declined during cheap land trade during mongols. Like silk road, network of many routes. Wide range of resources available. Monsoon winds helped Swahili and Arab traders. They came regularly. Able to predict down to week sometimes, made trade predictable. Encorporated many more people than Silk Road. For the most part, muslim merchants dominated especially on the east african coast because they had money to build ships. Bulk trade because of ships, not strapped onto camels. Timber came from africa, as well as raw goods like ivory, animal skins, spices, slaves and gold. Africa imported finished goods like silk, porcelain from china, spices and cotton from India, and black pepper from Sri Lanka. Triangular lateen sails allowed travel apart from monsoon winds. [6][9] Trade also came from Persia, Arabia, Greece, Egypt, Rome, Assyria, Sumeria, and Phoenicia. [10]

Slavery pasted from Arab slave trade

Author N'Diaye estimates that as many as 17 million people were sold into slavery on the coast of the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, and North Africa, and approximately 5 million African slaves were transported by Muslim slave traders via Red Sea, Indian Ocean, and Sahara desert to other parts of the world between 1500 and 1900.[12] Historian Lodhi challenged N'Diaye's figure saying "17 million? How is that possible if the total population of Africa at that time might not even have been 40 million? These statistics did not exist back then."[13]

he Zanj Rebellion, a series of uprisings that took place between 869 and 883 AD near the city of Basra (also known as Basara), situated in present-day Iraq, is believed to have involved enslaved Zanj that had originally been captured from the African Great Lakes region and areas further south in East Africa.[14] It grew to involve over 500,000 slaves and free men who were imported from across the Muslim empire and claimed over "tens of thousands of lives in lower Iraq".[16] The Zanj who were taken as slaves to the Middle East were often used in strenuous agricultural work.[15] As the plantation economy boomed and the Arabs became richer, agriculture and other manual labor work was thought to be demeaning. The resulting labor shortage led to an increased slave market.

It is certain that large numbers of slaves were exported from eastern Africa; the best evidence for this is the magnitude of the Zanj revolt in Iraq in the 9th century, though not all of the slaves involved were Zanj.

Portuguese pasted from History of Africa

The Portuguese arrived in 1498. On a mission to economically control and Christianize the Swahili coast, the Portuguese attacked Kilwa first in 1505 and other cities later. Because of Swahili resistance, the Portuguese attempt at establishing commercial control was never successful. By the late 17th century, Portuguese authority on the Swahili coast began to diminish. With the help of Omani Arabs, by 1729 the Portuguese presence had been removed. The Swahili coast eventually became part of the Sultanate of Oman. Trade recovered, but it did not regain the levels of the past.[35]

Portuguese pasted from Zanzibar

The Portuguese arrived in East Africa in 1498, where they found a series of independent towns on the coast, with Muslim Arabic-speaking elites. While the Portuguese travelers describe them as 'black' they made a clear distinction between the Muslim and non-Muslim populations.[36] Their relations with these leaders were mostly hostile, but during the sixteenth century they firmly established their power, and ruled with the aid of tributary sultans. The Portuguese presence was relatively limited, leaving administration in the hands of preexisting local leaders and power structures. This system lasted until 1631, when the Sultan of Mombasa massacred the Portuguese inhabitants. For the remainder of their rule, the Portuguese appointed European governors. The strangling of trade and diminished local power led the Swahili elites in Mombasa and Zanzibar to invite Omani aristocrats to assist them in driving the Europeans out.[37]

Original Portuguese

The portuguese attacked cities such as Kilwa, Zanzibar, and Mombasa. Later they were replaced by other European colonial powers, but Mozambique remained a Portuguese colony until 1975. [9]

Modern Day

Nairobi

Nairobi (/naɪˈroʊbi/) is the capital and the largest city of Kenya. The name comes from the Maasai phrase Enkare Nairobi, which translates to "cool water", a reference to the Nairobi River which flows through the city. The city proper had a population of 3,138,369 in the 2009 census, while the metropolitan area has a population of 6,547,547. The city is popularly referred to as the Green City in the Sun.[38]

Nairobi was founded in 1899 by the colonial authorities in British East Africa, as a rail depot on the Uganda Railway.[39]

Tanzania

Before unification in 1964 of United Republic of Tanzania, Zanzibar and coastal culture very different from inland Tanganyika culture. Marriage of convenience. friction between the two cultures. However, Tanzania is an example of cooperation between different cultures and of overcoming ethnic strife caused by artificial European boundaries.[10]

Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (/ˌdɑːr ɛs səˈlɑːm/; from Template:Lang-ar), or simply Dar, formerly known as Mzizima,[pronunciation?] is the former capital as well as the most populous city in Tanzania and a regionally important economic centre.[40] Located on the Swahili coast, the city is one of the fastest growing cities in the world.[41]

Until 1974, Dar es Salaam served as Tanzania’s capital city, at which point the capital city commenced transferring to Dodoma, which was officially completed in 1996. However, as of 2018, it remains a focus of central government bureaucracy, although this is in the process of fully moving to Dodoma. It is Tanzania's most prominent city in arts, fashion, media, music, film and television, and is a leading financial centre. The city is the leading arrival and departure point for most tourists who visit Tanzania, including the national parks for safaris and the islands of Unguja and Pemba.

The region had a population of 4,364,541 as of the official 2012 census.[42]: 2

| This is a user sandbox of Kmubeen. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

- ^ Felix A. Chami, "Kaole and the Swahili World," in Southern Africa and the Swahili World (2002), 6.

- ^ A. Lodhi (2000), Oriental influences in Swahili: a study in language and culture contacts, ISBN 978-9173463775, pp. 72-84

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Swahili Coast". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- ^ a b c d e f Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania, retrieved 2019-10-30

- ^ "Contagion of discontent: Muslim extremism spreads down east Africa coastline," The Economist (3 November 2012)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Int'l Commerce, Snorkeling Camels, and The Indian Ocean Trade: Crash Course World History #18, retrieved 2019-10-30

- ^ a b Horton, Mark; Middleton, John (2000). The Swahili: The social landscape of a mercantile society. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 063118919X.

- ^ Philippe Beaujard "East Africa, the Comoros Islands and Madagascar before the sixteenth century, Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa" (2007)

- ^ a b c d e "AFRICA - Explore the Regions - Swahili Coast". www.thirteen.org. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ a b c Finke, Jens (2010-01-04). The Rough Guide to Tanzania. Penguin. ISBN 9781405380188.

- ^ BBC Kilwa Pot Sherds http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/about/transcripts/episode60/

- ^ a b "Focus on the slave trade". BBC. 3 September 2001. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017.

- ^ a b Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "East Africa's forgotten slave trade | DW | 22.08.2019". DW.COM.

- ^ a b Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 585. ISBN 978-0313332739.

- ^ a b "Islam, From Arab To Islamic Empire: The Early Abbasid Era". History-world.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ^ a b Asquith, Christina. "Revisiting the Zanj and Re-Visioning Revolt: Complexities of the Zanj Conflict – 868-883 Ad – slave revolt in Iraq". Questia.com. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ^ a b c d e Perkins, John (2015-12-25). "The Indian Ocean and Swahili Coast coins, international networks and local developments". Afriques. Débats, méthodes et terrains d’histoire (06). doi:10.4000/afriques.1769. ISSN 2108-6796.

- ^ a b c Crowther, Alison; Faulkner, Patrick; Prendergast, Mary E.; Morales, Eréndira M. Quintana; Horton, Mark; Wilmsen, Edwin; Kotarba-Morley, Anna M.; Christie, Annalisa; Petek, Nik; Tibesasa, Ruth; Douka, Katerina (2016-05-03). "Coastal Subsistence, Maritime Trade, and the Colonization of Small Offshore Islands in Eastern African Prehistory". The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 11 (2): 211–237. doi:10.1080/15564894.2016.1188334. ISSN 1556-4894.

- ^ "Historic Sites of Kilwa". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ^ a b c "The Story of Africa| BBC World Service". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ^ "Historic Sites of Kilwa". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ^ "Exotic Zanzibar and its seafood". Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Ingrams 1967, p. 162

- ^ Appiah; Gates, Henry Louis Jr., eds. (1999), Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, New York: Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-00071-1, OCLC 41649745

- ^ a b "dishes". www.mwambao.com. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ a b "Development and Promotion of Extractive Industries and Mineral Value Addition". East African Community.

- ^ a b "HOME – Home". Swahililanguage.stanford.edu. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

After Arabic, Swahili is the most widely used African language but the number of its speakers is another area in which there is little agreement. The most commonly mentioned numbers are 50, 80, and 100 million people. [...] The number of its native speakers has been placed at just under 2 million.

- ^ a b c d e "History and Origin of Swahili". www.swahilihub.com. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ a b c d "Swahili - Art & Life in Africa - The University of Iowa Museum of Art". africa.uima.uiowa.edu. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ Nurse, Derek; Spear, Thomas (1985). The Swahili: Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society, 800-1500. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ^ A. Lodhi (2000), Oriental influences in Swahili: a study in language and culture contacts, ISBN 978-9173463775, pp. 72-84

- ^ Constance Jones and James D. Ryan, Encyclopedia of Hinduism, ISBN 978-0816073368, pp. 10-12

- ^ a b Kusimba, Chapurkha M. (1999). The Rise and Fall of Swahili States. Altamira Press.

- ^ DE V. ALLEN, J. (1982). "THE "SHIRAZI" PROBLEM IN EAST AFRICAN COASTAL HISTORY". Paideuma. 28: 9–27. ISSN 0078-7809.

- ^ Page, Willie F. (2001). pp. 263–264

- ^ Prestholdt, Jeremy. "Portuguese Conceptual Categories and the “Other” Encounter on the Swahili Coast." Journal of Asian American Studies, Volume 36, Issue 4, 390.

- ^ Sir Charles Eliot, K.C.M.G., The East Africa Protectorate, London: Edward Arnold, 1905, digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 (PDF format).

- ^ Pulse Africa. "Not to be Missed: Nairobi 'Green City in the Sun'". pulseafrica.com. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- ^ Roger S. Greenway, Timothy M. Monsma, Cities: missions' new frontier, (Baker Book House: 1989), p.163.

- ^ "Major urban areas - population". cia.gov. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ "Where is the fastest growing city in the world?". theguardian.com. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ Population Distribution by Administrative Units, United Republic of Tanzania, 2013 Archived May 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine