Digital Command Control: Difference between revisions

clarified sections |

→How DCC works: correct |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

==How DCC works== |

==How DCC works== |

||

[[File:DCCsig.png|thumb|right|A short, mid packet, example of a DCC signal and its encoded bit stream]] |

[[File:DCCsig.png|thumb|right|A short, mid packet, example of a DCC signal and its encoded bit stream]] |

||

The system consists of power supplies, command stations, and decoders. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

The voltage to the track is a bipolar |

The voltage to the track is a bipolar [[alternating current]] (AC) signal. The DCC signal does not follow a [[sine wave]]. Instead, the command station quickly switches the direction of the DC voltage, resulting in a modulated [[pulse wave]]. The length of time the voltage is applied in each direction provides the method for encoding data. To represent a [[binary numeral system|binary]] one, the time is short (nominally 58 µs for a half cycle), while a zero is represented by a longer period (nominally at least 100 µs for a half cycle). |

||

Each locomotive is equipped with a mobile [[Dcc:Decoder|DCC decoder]] that takes the signals from the track and, after [[rectifier|rectification]], routes power to the [[electric motor]] as requested. Each decoder is given a unique running number ([[Address space|address]]) for the layout, and will not act on commands intended for a different decoder, thus providing independent control of locomotives anywhere on the layout, without special wiring requirements. Power can also be routed to lights, smoke generators, and sound generators. These extra functions can be operated remotely from the DCC controller. [[Dcc:Stationary decoder|Stationary decoders]] can also receive commands from the controller in a similar way to allow control of turnouts, uncouplers, other operating accessories (such as station announcements) and lights. |

Each locomotive is equipped with a mobile [[Dcc:Decoder|DCC decoder]] that takes the signals from the track and, after [[rectifier|rectification]], routes power to the [[electric motor]] as requested. Each decoder is given a unique running number ([[Address space|address]]) for the layout, and will not act on commands intended for a different decoder, thus providing independent control of locomotives anywhere on the layout, without special wiring requirements. Power can also be routed to lights, smoke generators, and sound generators. These extra functions can be operated remotely from the DCC controller. [[Dcc:Stationary decoder|Stationary decoders]] can also receive commands from the controller in a similar way to allow control of turnouts, uncouplers, other operating accessories (such as station announcements) and lights. |

||

Revision as of 10:25, 11 January 2020

Digital Command Control (DCC) is a standard for a system to operate model railways digitally. When equipped with Digital Command Control, locomotives on the same electrical section of track can be independently controlled.

The DCC protocol is defined by the Digital Command Control Working group of the National Model Railroad Association (NMRA). The NMRA has trademarked the term DCC, so while the term Digital Command Control is sometimes used to describe any digital model railway control system, strictly speaking it refers to NMRA DCC.

History and protocols

A digital command control system was developed (under contract by Lenz Elektronik GmbH of Germany) in the 1980s for two German model railway manufacturers, Märklin and Arnold. The first digital decoders that Lenz produced appeared on the market early 1989 for Arnold (N) and mid 1990 for Märklin (Z, H0 and 1; Digital=).[1] Märklin and Arnold exited the agreement over patent issues, but Lenz continued to develop the system. In 1992 Stan Ames, who later chaired the NMRA/DCC Working Group, investigated the Märklin/Lenz system as possible candidate for the NMRA/DCC standards. When the NMRA Command Control committee requested submissions from manufacturers for its proposed command control standard in the 1990s, Märklin and Keller Engineering submitted their systems for evaluation.[2] The committee was impressed by the Märklin/Lenz system and had settled on digital early in the process. The NMRA eventually licensed the protocol from Lenz and extended it. The system was later named Digital Command Control. The proposed standard was published in the October 1993 issue of Model Railroader magazine prior to its adoption.

The DCC protocol is the subject of two standards published by the NMRA: S-9.1 specifies the electrical standard, and S-9.2 specifies the communications standard. Several recommended practices documents are also available.

The DCC protocol defines signal levels and timings on the track. DCC does not specify the protocol used between the DCC command station and other components such as additional throttles. A variety of proprietary standards exist, and in general, command stations from one vendor are not compatible with throttles from another vendor.

Railcom

In 2006 Lenz, together with Kühn, Zimo and Tams, started development of an extension to the DCC protocol to allow a feedback channel from decoders to the command station. This feedback channel can typically be used to signal which train occupies a certain section, but as well to inform the command station of the actual speed of an engine. This feedback channel is known under the name Railcom, and was standardized in 2007 as NMRA RP 9.3.1.

Quoting "NMRA Standards and Recommended Practices":[3]

S-9.3 DCC Bi-Directional Communications Standard

S-9.3.1 (discontinued)

S-9.3.2 DCC Basic Decoder Transmission - (updated 12/20/2012) UNDER REVISION

How DCC works

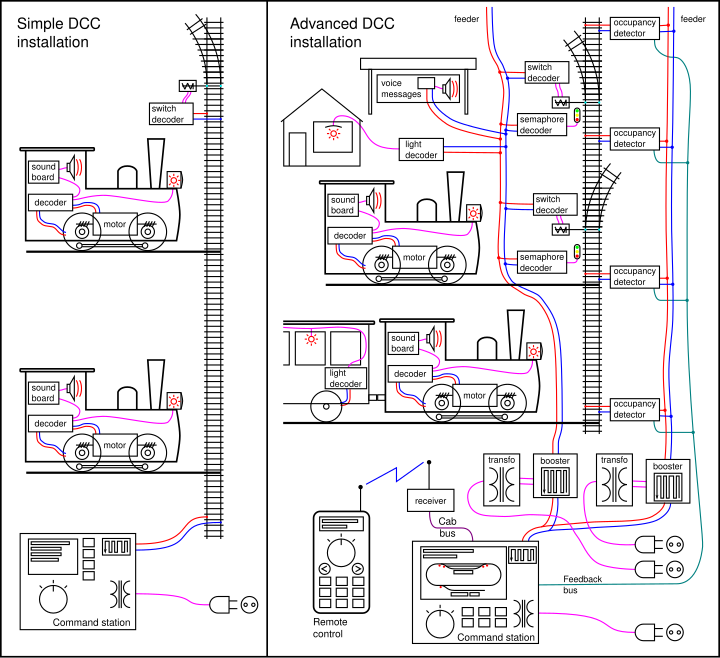

The system consists of power supplies, command stations, and decoders.

A DCC command station, in combination with its power supply, modulates the voltage on the track to encode digital messages while providing electric power. For large systems boosters command stations are used to relay the messages and provide extra power.

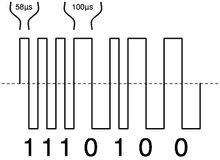

The voltage to the track is a bipolar alternating current (AC) signal. The DCC signal does not follow a sine wave. Instead, the command station quickly switches the direction of the DC voltage, resulting in a modulated pulse wave. The length of time the voltage is applied in each direction provides the method for encoding data. To represent a binary one, the time is short (nominally 58 µs for a half cycle), while a zero is represented by a longer period (nominally at least 100 µs for a half cycle).

Each locomotive is equipped with a mobile DCC decoder that takes the signals from the track and, after rectification, routes power to the electric motor as requested. Each decoder is given a unique running number (address) for the layout, and will not act on commands intended for a different decoder, thus providing independent control of locomotives anywhere on the layout, without special wiring requirements. Power can also be routed to lights, smoke generators, and sound generators. These extra functions can be operated remotely from the DCC controller. Stationary decoders can also receive commands from the controller in a similar way to allow control of turnouts, uncouplers, other operating accessories (such as station announcements) and lights.

In a segment of DCC-powered track, it is possible to power a single analog model locomotive by itself (or in addition to the DCC equipped engines), depending on the choice of commercially available base systems. The technique is known as zero stretching. Either the high or the low pulse of the zero bits can be extended to make the average voltage (and thus the current) either forward or reverse. However, because the raw power contains a heavy AC component, DC motors heat up much more quickly than they would on DC power, and some motor types (particularly coreless electric motors) can be damaged by a DCC signal.

Advantages over analog control

The great advantage of digital control is the individual control of locomotives wherever they are on the layout. With analog control, operating more than one locomotive independently requires the track to be wired into separate "blocks" each having switches to select the controller. Using digital control, locomotives may be controlled wherever they are located.

Digital locomotive decoders often include "inertia" simulation, where the locomotive will gradually increase or decrease speeds in a realistic manner. Many decoders will also constantly adjust motor power to maintain constant speed. Most digital controllers allow an operator to set the speed of one locomotive and then select another locomotive to control its speed while the previous locomotive maintains its speed.

Recent developments include on-board sound modules for locomotives as small as N scale.

Wiring requirements are generally reduced compared to a conventional DC powered layout. With digital control of accessories, the wiring is distributed to accessory decoders rather than being individually connected to a central control panel. For portable layouts this can greatly reduce the number of inter-board connections - only the digital signal and any accessory power supplies need cross baseboard joins.

Example schematics

Competing systems

There are two main European alternatives: Selectrix, an open Normen Europäischer Modellbahnen (NEM) standard, and the Märklin Digital proprietary system. The US Rail-Lynx system provides power with a fixed voltage to the rails while commands are sent digitally using infrared light.

Other systems include the Digital Command System and Trainmaster Command Control.

Several major manufacturers (including Märklin, Roco, Hornby and Bachmann), have entered the DCC market alongside makers which specialize in it (including Lenz, Digitrax, ESU, ZIMO, Kühn, Tams, North Coast Engineering (NCE), and CVP Products' EasyDCC, Sound Traxx, Lok Sound, Train Control Systems and ZTC). Most Selectrix central units are multi protocol units supporting DCC fully or partially (e.g. Rautenhaus, Stärz and MTTM).

See also

References

- ^ Werner Kraus. (1991). Modellbahn Digital Praxis: Aufbau, Betrieb und Selbstbau. Düsseldorf: Alba. ISBN 3-87094-567-2

- ^ DCC Home Page "DCC Home Page", NMRA.org, accessed December 19, 2010.

- ^ DCC Home Page "S-9.3.1 (discontinued)", NMRA.org, accessed November 23, 2018.

External links

- NMRA Standards and Recommended Practices page

- The NMRA's trademarked DCC logo

- DCC History at the DCCWiki

- The DCCWiki

- Wiring for DCC

- Hornby DCC Product Information Page

- Model Rectifier Corporation - Manufacturer of DCC related products

- Digitrax - Manufacturer of DCC related products, Mobile Decoders, Starter Sets, etc

- Train Control Systems - Manufacturer of DCC related products

- NCE Power Pro System - Manufacturer of DCC related products

- CVP's EasyDCC System - Manufacturer of DCC related products

- OpenDCC - An open project for building your own decoders, command stations etc.