Popeye (film): Difference between revisions

Wikilink Stalag because I only half knew the joke from watching war films. (Alternatively instead of a link the text could be expanded to make it clearer, something like "Robins joked it was like a prison camp, calling it Stalag Altman") |

Feuertrinker (talk | contribs) →Release: initials space Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

==Release== |

==Release== |

||

{{Expand section|date=May 2010}} |

{{Expand section|date=May 2010}} |

||

''Popeye'' [[Film premiere|premiered]] at the [[TCL Chinese Theatre|Mann's Chinese Theater]] in Los Angeles on December 6, 1980, two days before what would have been E.C. Segar's 86th birthday.<ref name=plecki/>{{rp|123}} |

''Popeye'' [[Film premiere|premiered]] at the [[TCL Chinese Theatre|Mann's Chinese Theater]] in Los Angeles on December 6, 1980, two days before what would have been E. C. Segar's 86th birthday.<ref name=plecki/>{{rp|123}} |

||

===Box office=== |

===Box office=== |

||

Revision as of 22:49, 22 April 2020

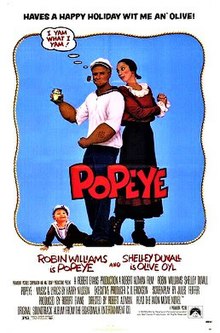

| Popeye | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Altman |

| Screenplay by | Jules Feiffer |

| Produced by | Robert Evans |

| Starring | Robin Williams Shelley Duvall |

| Cinematography | Giuseppe Rotunno |

| Edited by | Tony Lombardo (supervising) John W. Holmes David A. Simmons |

| Music by | Harry Nilsson |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures (North America) Buena Vista International Distribution (International) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20 million[citation needed] |

| Box office | $60 million[1] |

Popeye is a 1980 American musical comedy film directed by Robert Altman and distributed by Paramount Pictures. It is based on E. C. Segar's comics character of the same name. It was written by Jules Feiffer and stars Robin Williams[2] as Popeye the Sailor Man and Shelley Duvall as Olive Oyl. Its story follows Popeye's adventures as he arrives in the town of Sweethaven.

The film premiered on December 6, 1980 in Los Angeles, California. It grossed $6.3 million in its opening weekend and $49.8 million worldwide, against a budget of $20 million.[3] It received generally positive reviews from critics.[4][5]

Plot

Popeye, a strong sailor, arrives at the small coastal town of Sweethaven while searching for his missing father. He rents a room at the Oyl family's boarding house where the Oyls plan to have their daughter Olive become engaged to Captain Bluto, a powerful, perpetually angry bully who runs the town in the name of the mysterious Commodore. However, on the night of the engagement party, Olive sneaks out after discovering that the only attribute she can report for her bullying fiancé is size. She encounters Popeye, who failed to fit in with the townsfolk at the party. The two eventually come across an abandoned baby in a basket. Popeye and Olive adopt the child, naming him Swee'Pea after the town Sweethaven, and the two return to the Oyls' home. Bluto finds out about this encounter, which results in him declaring heavy taxation for the Oyls' property and possessions out of rage. A greedy taxman follows up on Bluto's demand, but Popeye helps the Oyls' financial situation by winning a hefty prize from defeating a boxer named Oxblood Oxheart.

The next day, Popeye discovers that Swee'Pea can predict the future by whistling when he hears the correct answer to a question. Wimpy, the constantly hungry local mooch and a petty gambler, also notices this and asks Popeye and Olive to take Swee'Pea out for a walk. However, he actually takes him to the "horse races" (actually a mechanical carnival horse game) and wins two games. Hearing of this, Olive and her whole family decide to get in on the action and use Swee'Pea to win, but an outraged Popeye finds out and takes Swee'Pea away.

Later, after Popeye throws the taxman into the sea (simultaneously earning the respect of the town), Wimpy then kidnaps the child at Bluto's orders. Wimpy informs Popeye about the kidnapping, after being threatened by Olive. Popeye goes to the Commodore's ship, where he finds out that the Commodore, who has actually been held a prisoner by Bluto all this time, is indeed Popeye's father, Poopdeck Pappy, who accepts that Popeye is his son after exposing Popeye's hatred of Spinach. Meanwhile, Bluto kidnaps Olive and sets sail with her and Swee'Pea to find buried treasure promised by Pappy. Popeye, Pappy, Wimpy and the Oyl family board Pappy's ship to chase Bluto to Scab Island, a desolate island in the middle of the ocean.

Popeye catches up to Bluto and fights him, but despite his determination, Popeye is overpowered. During the fight, Pappy recovers his treasure and opens the chest to reveal a collection of personal sentimental items from Popeye's infancy, including a few cans of spinach. A gigantic octopus awakens and attacks Olive from underwater (after Pappy saves Swee'Pea from a similar fate). With Popeye in a choke hold, Pappy throws him a can of spinach; Bluto, recognizing Popeye's dislike for spinach, force-feeds him the can before throwing him into the water. The spinach revitalizes Popeye and boosts his strength, helping him to defeat both Bluto and the giant octopus. Popeye celebrates his victory and his new-found appreciation of spinach while Bluto swims off, having literally turned yellow.

Cast

- Robin Williams as Popeye

- Jack Mercer as the voice of Popeye in the opening

- Shelley Duvall as Olive Oyl

- Paul L. Smith as Bluto

- John Wallace as Bluto's singing voice

- Paul Dooley as J. Wellington Wimpy

- Richard Libertini as George W. Geezil

- Ray Walston as Poopdeck Pappy

- Donald Moffat as The Taxman

- MacIntyre Dixon as Cole Oyl

- Roberta Maxwell as Nana Oyl

- Donovan Scott as Castor Oyl

- Allan F. Nicholls as Rough House

- Wesley Ivan Hurt as Swee'Pea

- Bill Irwin as Ham Gravy

- Sharon Kinney as Cherry

- Peter Bray as Oxblood Oxheart

- Linda Hunt as Mrs. Oxheart

- Geoff Hoyle as Scoop

- Wayne Robson as Chizzelflint

- Klaus Voormann as Von Schnitzel

- Van Dyke Parks as Hoagy the Piano Player

- Dennis Franz as Spike

- Carlos Brown as Slug

Production

According to James Robert Parish, in his book Fiasco: A History of Hollywood's Iconic Flops, the idea for the Popeye musical had its basis in the bidding war for the film adaptation of the Broadway musical Annie between the two major studios vying for the rights, Columbia and Paramount. When Robert Evans found out that Paramount had lost the bidding for Annie, he held an executive meeting in which he asked about comic strip characters which the studio held the rights to which could also be used in order to create a movie musical, and one attendee said "Popeye".

At that time, even though King Features Syndicate (now a unit of Hearst) retained the television rights to Popeye and related characters, with Hanna-Barbera then producing the series The All-New Popeye Hour under license from King Features, Paramount had long held the theatrical rights to the Popeye character, due to the studio releasing Popeye cartoons produced by Fleischer Studios and Famous Studios, respectively, from 1932 to 1957.

Evans commissioned Jules Feiffer to write a script. In 1977, he said he wanted Dustin Hoffman to play Popeye opposite Lily Tomlin as Olive Oyl, with John Schlesinger directing.[6] Hoffman later dropped out due to creative differences with Feiffer. Gilda Radner, then a hot new star as an original cast member of Saturday Night Live, was also considered for the Olive Oyl role. However, Radner's manager Bernie Brillstein later wrote how he discouraged her from taking the part due his concerns about the quality of the script and worries about her working for months on an isolated set with Evans and Altman (both known for erratic behavior and unorthodox creative methods).[7]

In December 1979, Disney joined the film as part of a two-picture co-production deal with Paramount which also included Dragonslayer. Disney acquired the foreign rights through its Buena Vista unit; the deal was motivated by the drawing power that the studio's films had in Europe.

The film was shot in Malta. The elaborate Sweethaven set was constructed beyond what was needed for filming, adding to the cost and complexity of the production, along with a recording studio, editing facilities, and other buildings related to the production, including living quarters. The set still exists, and it is a popular tourist attraction known as Popeye Village. According to Parish, Robin Williams referred to this set as "Stalag Altman".

Parish notes a variety of other production problems. Feiffer's script went through rewrites during the production, and he expressed concern too much screen time was being devoted to minor characters. He also disliked Nilsson's songs, feeling they weren't right for the film. The original inflatable arms designed for the muscle-bound Popeye did not look satisfactory, so new ones were commissioned and made in Italy, leaving Altman to film scenes not showing them until the new ones arrived. Altman also had the cast singing their musical numbers live—contrary to standard convention for a movie musical where songs are recorded first in a studio and lip-synched—causing sound quality problems. Williams also had to re-record his dialogue after running into trouble with his character's mumbling style, a by-product of talking with a pipe in his mouth, and his affinity for ad-libs also led to clashes with the director. The final battle involving the octopus led to more headaches when the mechanical beast failed to work properly. After the production cost rose beyond $20 million, Paramount ordered Altman to wrap filming and return to California with what he had.

Release

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

Popeye premiered at the Mann's Chinese Theater in Los Angeles on December 6, 1980, two days before what would have been E. C. Segar's 86th birthday.[8]: 123

Box office

The film grossed $6 million on its opening weekend in the U.S., and made $32,000,000 after 32 days.[8]: 123–124 The film earned $49,823,037[9] at the United States box office — more than double the film's budget — and a worldwide total of $60 million.[1]: 88

Film Comment later wrote "Before the film's release, industry wags were calling it 'Evansgate'" but "Apparently the film has caught on solidly with young children." [10]

Although the film's gross was decent, it was nowhere near the blockbuster that Paramount and Disney had expected, and was thus written off as a disappointment.[11]

Critical response

The film received overall mixed reviews: Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a rating of 61% rating based on reviews from 31 critics, with the critical consensus stating [that] "Altman's take on the iconic cartoon is messy and wildly uneven, but its robust humor and manic charm are hard to resist."[4] Metacritic gives it a score of 64 out of 100, based on reviews from 14 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[5]

Some reviews were highly favorable. Roger Ebert gave the film 3.5 stars out of 4, writing that Duvall was "born to play" Olive Oyl, and with Popeye Altman had proved "it is possible to take the broad strokes of a comic strip and turn them into sophisticated entertainment."[12] Gene Siskel also awarded 3.5 out of 4, writing that the first 30 minutes were "tedious and totally without a point of view," but once Swee'pea was introduced the film "then becomes quite entertaining and, in a few scenes, very special."[13] Richard Combs of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, "In its own idiosyncratic fashion, it works."[14]

Other critics were unfavorable, such as Leonard Maltin, who described the picture as a bomb: "E.C. Segar's beloved sailorman boards a sinking ship in this astonishingly boring movie. A game cast does its best with an unfunny script, cluttered staging, and some alleged songs. Tune in a couple hours' worth of Max Fleischer cartoons instead; you'll be much better off."[15][16] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called it "a thoroughly charming, immensely appealing mess of a movie, often high-spirited and witty, occasionally pretentious and flat, sometimes robustly funny and frequently unintelligible. It is, in short, a very mixed bag."[17] Variety wrote that all involved "fail to bring the characters to life at the sacrifice of a large initial chunk of the film. It's only when they allow the characters to fall back on their cartoon craziness that the picture works at all."[18][19] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post wrote, "While there are things to like in this elaborately stylized, exasperating musical slapstick fantasy ... they emerge haphazardly and flit in and out of a precarious setting."[20] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times described the film as "rarely uninteresting but seldom entirely satisfying," and thought that the adult tone of the dialogue left it "uncertain what the film's target audience is intended to be."[21]

Soundtrack

Original release

| Popeye | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | ||||

| Released | 1981 (reissued in 2000, 2016, 2017) | |||

| Recorded | 1980 | |||

| Genre | Pop, show tune | |||

| Label | Boardwalk (1981) Walt Disney/Geffen (2000, 2017) Varèse Sarabande/Universal (2016, 2017) | |||

| Producer | Harry Nilsson | |||

| Harry Nilsson chronology | ||||

| ||||

The soundtrack was composed by Harry Nilsson, who took a break from producing his album Flash Harry to write the score for the film. He wrote all the original songs and co-produced the music with producer Bruce Robb at Cherokee Studios. The soundtrack in the film was unusual in that the actors sang some of the songs "live". For that reason, the studio album did not quite match the tracks heard in the film. Van Dyke Parks is credited as music arranger.

In the U.S. trailer for the film, which contained the song "I Yam What I Yam", the version heard of the song was from the soundtrack album, not the film.

"I'm Popeye the Sailor Man" was composed by Sammy Lerner for the original Max Fleischer cartoon.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "I Yam What I Yam" | 2:16 |

| 2. | "He Needs Me" | 3:33 |

| 3. | "Swee' Pea's Lullaby" | 2:06 |

| 4. | "Din' We" | 3:06 |

| 5. | "Sweethaven—An Anthem" | 2:56 |

| 6. | "Blow Me Down" | 4:07 |

| 7. | "Sailin'" | 2:48 |

| 8. | "It's Not Easy Being Me" | 2:20 |

| 9. | "He's Large" | 4:19 |

| 10. | "I'm Mean" | 2:33 |

| 11. | "Kids" | 4:23 |

| 12. | "I'm Popeye the Sailor Man" | 1:19 |

The song "Everything Is Food" was not included on the album, while the song "Din' We" (which was cut from the film) was included. In 2016, a vinyl-only limited-edition version of the album was released with two bonus tracks by Varèse Sarabande for Record Store Day Black Friday.

2017 deluxe edition

In 2017, Varese Sarabande released a deluxe edition that places the songs into the original order of the film, reinstates "Everything Is Food" and includes a second disc of demo versions of the songs sung by Nilsson and the cast.[22][23]

- Disc 1

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Sweethaven" | 2:53 |

| 2. | "Blow Me Down" | 4:09 |

| 3. | "Everything Is Food" | 3:08 |

| 4. | "Rough House Fight" | :43 |

| 5. | "He's Large" | 4:20 |

| 6. | "I'm Mean" | 2:35 |

| 7. | "Sailin'" | 2:47 |

| 8. | "March Through Town" | :48 |

| 9. | "I Yam What I Yam" | 2:16 |

| 10. | "The Grand Finale" | 1:34 |

| 11. | "He Needs Me" | 3:33 |

| 12. | "Swee'Pea's Lullaby" | 2:04 |

| 13. | "Din' We" | 3:05 |

| 14. | "It's Not Easy Being Me" | 2:18 |

| 15. | "Kids" | 4:27 |

| 16. | "Skeleton Cave" | 2:04 |

| 17. | "Now Listen Kid / To the Rescue / Mr. Eye Is Trapped / Back into Action" | 5:04 |

| 18. | "Saved / Still at It / The Treasure / What? More Fighting / Pap’s Boy / Olive & the Octopus / What’s Up Pop / Popeye Triumphant" | 3:09 |

| 19. | "I'm Popeye the Sailor Man" | 1:22 |

| 20. | "End Title Medley" | 3:34 |

- Disc 2

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Sweethaven" | 3:03 |

| 2. | "I'm Mean" | 3:21 |

| 3. | "Swee'Pea's Lullaby" | 2:50 |

| 4. | "Blow Me Down" | 3:02 |

| 5. | "Everything Is Food" | 3:43 |

| 6. | "He Needs Me" | 3:09 |

| 7. | "Everybody's Got to Eat" | 3:24 |

| 8. | "Sail with Me" | 2:53 |

| 9. | "I Yam What I Yam" | 3:08 |

| 10. | "It's Not Easy Being Me" | 2:24 |

| 11. | "Kids" | 3:52 |

| 12. | "I'm Popeye the Sailor Man" | 2:58 |

| 13. | "I'm Mean" | 2:59 |

| 14. | "He Needs Me" | 9:29 |

| 15. | "Everybody's Got to Eat" | 2:05 |

| 16. | "Din' We" | 3:02 |

| 17. | "Sailin'" | 4:52 |

| 18. | "I'd Rather Be Me" | 6:30 |

References

- ^ a b O'Brien, Daniel (1995). Robert Altman: Hollywood Survivor. New York: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-0791-9.

- ^ Spitznagel, Eric (August 12, 2014). "Popeye Is the Best Movie Robin Williams Ever Made". Vanity Fair. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ "Popeye". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "Popeye (1980)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ a b "Popeye". Metacritic.

- ^ At the Movies: Producer Sets Hoffman's Sail For 'Popeye' Flatley, Guy. New York Times (1923-Current file) [New York, N.Y] October 14, 1977: 58.

- ^ Bernie Brillstein, Where Did I Go Right? You're No One in Hollywood Unless Someone Wants You Dead (1999, Little, Brown and Company)

- ^ a b Plecki, Gerard (1985). Robert Altman. Boston: Twayne Publishers (G.K. Hall & Company/ITT). ISBN 0-8057-9303-8.

- ^ "Box office statistics for Popeye (1980)". The Numbers. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ The Sixth Annual Grosses Gloss Meisel, Myron. Film Comment; New York Vol. 17, Iss. 2, (Mar/Apr 1981): 64-72,80.

- ^ Prince, Stephen (2000) A New Pot of Gold: Hollywood Under the Electronic Rainbow, 1980-1989 (p. 222). University of California Press, Berkeley/Los Angeles, California. ISBN 0-520-23266-6

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Popeye". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 12, 1980). "First-rate fairy tale for adults". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 3.

- ^ Combs, Richard (March 1981). "Popeye". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 48 (566): 55.

- ^ Martin, Leonard (2015). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide. Signet Books. p. 1113. ISBN 978-0-451-46849-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20181219171531/https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1989-11-16-8903100044-story.html Quote: Even so, Maltin considers the film a ''bomb,'' calling it ''astonishly boring'' in his annual guide.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (December 12, 1980). "Screen: A Singing, Dancing, Feifferish Kind of 'Popeye'". The New York Times: C5.

- ^ "Popeye". Variety: 30. December 10, 1980.

- ^ https://variety.com/1979/film/reviews/popeye-2-1200424682/

- ^ Arnold, Gary (December 13, 1980). "Alas, Poor 'Popeye'". The Washington Post: D2.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (December 12, 1980). "A Miscalculated Voyage With 'Popeye'". Los Angeles Times. Part VI, p. 1, 10.

- ^ http://undertheradarmag.com/reviews/harry_nilsson_popeye_deluxe_edition_music_from_the_motion_picture_varese_sa

- ^ https://www.varesesarabande.com/products/popeye-deluxe-edition

Further reading

- Parish, James Robert (2006). Fiasco: A History of Hollywood's Iconic Flops. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-69159-4.

External links

- Popeye at IMDb

- Popeye at the TCM Movie Database

- Popeye at Box Office Mojo

- Popeye soundtrack

at AllMusic

at AllMusic - 1980 theatrical trailer on YouTube

- 1980 films

- 1980s romantic comedy films

- American adventure comedy films

- American musical comedy films

- American romantic comedy films

- American films

- American romantic musical films

- English-language films

- Films based on comic strips

- Films directed by Robert Altman

- Films produced by Robert Evans

- Films shot in Malta

- Films with screenplays by Jules Feiffer

- Harry Nilsson

- Live-action films based on animated series

- Live-action films based on comics

- Paramount Pictures films

- Pirate films

- Popeye

- Seafaring films

- Walt Disney Pictures films