Epichloë: Difference between revisions

R. S. Shaw (talk | contribs) →Bioactive compounds: link |

R. S. Shaw (talk | contribs) →Bioactive compounds: remove obsolete sentence |

||

| Line 279: | Line 279: | ||

Another group of epichloë alkaloids are the [[indole]]-[[diterpenoid]]s, such as lolitrem B, which are produced from the activity of several enzymes, including [[prenyltransferase]]s and various [[monooxygenase]]s.<ref name="Young2006"/> Both the ergoline and indole-diterpenoid alkaloids have [[biological activity]] against mammalian herbivores, and also activity against some insects.<ref name="Bush1997"/> Peramine is a pyrrolopyrazine alkaloid thought to be biosynthesized from the [[guanidine|guanidinium]]-group-containing amino acid <small>L</small>-[[arginine]], and pyrrolidine-5-[[carboxylate]], a precursor of <small>L</small>-[[proline]],<ref name="Tanaka2005"/> and is an insect-feeding deterrent. The [[loline alkaloids]]<ref name="Schardl2007"/> are 1-aminopyrrolizidines with an oxygen atom linking bridgehead carbons 2 and 7, and are biosynthesized from the amino acids <small>L</small>-proline and <small>L</small>-[[homoserine]].<ref name="Blankenship2005"/> The lolines have [[insecticide|insecticidal]] and insect-deterrent activities comparable to [[nicotine]].<ref name="Schardl2007"/> Loline accumulation is strongly induced in young growing tissues<ref name="Zhang2009"/> or by damage to the plant-fungus symbiotum.<ref name="Gonthier2008"/> Many, but not all, epichloae produce up to three classes of these alkaloids in various combinations and amounts.<ref name="Bush1997"/> Recently it has been shown that Epichloë uncinata infection and loline content afford Festulolium grasses protection from black beetle ([[Heteronychus arator]]).<ref name="Barker2014"/> |

Another group of epichloë alkaloids are the [[indole]]-[[diterpenoid]]s, such as lolitrem B, which are produced from the activity of several enzymes, including [[prenyltransferase]]s and various [[monooxygenase]]s.<ref name="Young2006"/> Both the ergoline and indole-diterpenoid alkaloids have [[biological activity]] against mammalian herbivores, and also activity against some insects.<ref name="Bush1997"/> Peramine is a pyrrolopyrazine alkaloid thought to be biosynthesized from the [[guanidine|guanidinium]]-group-containing amino acid <small>L</small>-[[arginine]], and pyrrolidine-5-[[carboxylate]], a precursor of <small>L</small>-[[proline]],<ref name="Tanaka2005"/> and is an insect-feeding deterrent. The [[loline alkaloids]]<ref name="Schardl2007"/> are 1-aminopyrrolizidines with an oxygen atom linking bridgehead carbons 2 and 7, and are biosynthesized from the amino acids <small>L</small>-proline and <small>L</small>-[[homoserine]].<ref name="Blankenship2005"/> The lolines have [[insecticide|insecticidal]] and insect-deterrent activities comparable to [[nicotine]].<ref name="Schardl2007"/> Loline accumulation is strongly induced in young growing tissues<ref name="Zhang2009"/> or by damage to the plant-fungus symbiotum.<ref name="Gonthier2008"/> Many, but not all, epichloae produce up to three classes of these alkaloids in various combinations and amounts.<ref name="Bush1997"/> Recently it has been shown that Epichloë uncinata infection and loline content afford Festulolium grasses protection from black beetle ([[Heteronychus arator]]).<ref name="Barker2014"/> |

||

Many species in ''Epichloë'' produce biologically active alkaloids, such as [[ergot alkaloid]]s, indole-diterpenoids (e.g., [[lolitrem B]]), [[loline alkaloids]], and the unusual [[guanidinium]] alkaloid, peramine.<ref name="Bush1997"/> |

Many species in ''Epichloë'' produce biologically active alkaloids, such as [[ergot alkaloid]]s, indole-diterpenoids (e.g., [[lolitrem B]]), [[loline alkaloids]], and the unusual [[guanidinium]] alkaloid, peramine.<ref name="Bush1997"/> |

||

==Ecology== |

==Ecology== |

||

Revision as of 06:54, 19 June 2020

| Epichloë | |

|---|---|

| |

| "Choke disease": Epichloë typhina stroma on bluegrass | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Genus: | Epichloë |

| Type species | |

| Epichloë typhina (Fr.) Tul. & C. Tul.

| |

| Diversity | |

| 35 species, see text | |

Epichloë is a genus of ascomycete fungi forming an endophytic symbiosis with grasses. Grass choke disease is a symptom in grasses induced by some Epichloë species, which form spore-bearing mats (stromata) on tillers and suppress the development of their host plant's inflorescence. For most of their life cycle however, Epichloë grow in the intercellular space of stems, leaves, inflorescences, and seeds of the grass plant without incurring symptoms of disease. In fact, they provide several benefits to their host, including the production of different herbivore-deterring alkaloids, increased stress resistance, and growth promotion.

Within the family Clavicipitaceae, Epichloë is embedded in a group of endophytic and plant pathogenic fungi, whose common ancestor probably derived from an animal pathogen. The genus includes both species with a sexually reproducing (teleomorphic) stage and asexual, anamorphic species. The latter were previously placed in the form genus Neotyphodium but included in Epichloë after molecular phylogenetics had shown asexual and sexual species to be intermingled in a single clade. Hybrid speciation has played an important role in the evolution of the genus.

Epichloë species are ecologically significant through their effects on host plants. Their presence has been shown to alter the composition of plant communities and food webs. Grass varieties, especially of tall fescue and ryegrass, with symbiotic Epichloë endophyte strains, are commercialised and used for pasture and turf.

Taxonomy

Elias Fries, in 1849, first defined Epichloë as a subgenus of Cordyceps.[1] As type species, he designated Cordyceps typhina,[1] originally described by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon.[2] The brothers Charles and Louis René Tulasne then raised the subgenus to genus rank in 1865.[3] Epichloë typhina would remain the only species in the genus until the discovery of fungal grass endophytes causing livestock intoxications in the 1970s and 1980s, which stimulated the description of new species.[4] Several species from Africa and Asia that develop stromata on grasses were split off as a separate genus Parepichloë in 1998.[5]

Many Epichloë species have forms that reproduce sexually, and several purely asexual species are closely related to them. These anamorphs were long classified separately: Morgan-Jones and Gams (1982) collected them in a section (Albo-lanosa) of genus Acremonium.[6] In a molecular phylogenetic study in 1996, Glenn and colleagues found the genus to be polyphyletic and proposed a new genus Neotyphodium for the anamorphic species related to Epichloë.[7] A number of species continued to be described in both genera until Leuchtmann and colleagues (2014) included most of the form genus Neotyphodium in Epichloë.[4] Phylogenetic studies had shown both genera to be intermingled, and the nomenclatural code required since 2011 that one single name be used for all stages of development of a fungal species. Only Neotyphodium starrii, of unclear status, and N. chilense, which is unrelated, were excluded from Epichloë.[4]

Species

As of 2020, there are 35 accepted species in the genus, with 3 subspecies and 6 varieties described. 14 species, 3 subspecies and 5 varieties are haploid. 21 species and 1 variety are hybrids (allopolyploids). Several taxa are only known as anamorphic (asexual) forms, most of which have previously been classified in Neotyphodium.[4]

| Haploid Taxa | Known Distribution | Sexual Reproduction | Vertical Transmission | Known Host Range | Reference to Species Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epichloë amarillans

J.F. White |

North America | Observed | Present | Agrostis hyemalis, Agrostis perennans, Calamagrostis canadensis, Elymus virginicus, Sphenopholis nitida, Sphenopholis obtusata, Sphenopholis × pallens, Ammophila breviligulata | White, James F. (1994). "Endophyte-host associations in grasses. XX. Structural and reproductive studies of Epichloë amarillans sp. nov. and comparisons to E. typhina". Mycologia. 86 (4): 571–580. doi:10.1080/00275514.1994.12026452. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë aotearoae

(C.D. Moon, C.O. Miles & Schardl) Leuchtm. & Schardl |

New Zealand, Australia | Not observed | Present | Echinopogon ovatus | Moon, Christina D.; Miles, Christopher O.; Järlfors, Ulla; Schardl, Christopher L. (2002). "The evolutionary origins of three new Neotyphodium endophyte species from grasses indigenous to the Southern Hemisphere". Mycologia. 94 (4): 694–711. doi:10.1080/15572536.2003.11833197. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë baconii

J.F. White |

Europe | Observed | Absent | Agrostis capillaris, Agrostis stolonifera, Calamagrostis villosa, Calamagrostis varia, Calamagrostis purpurea | White, James F. (1993). "Endophyte-host associations in grasses. XIX. A systematic study of some sympatric species of Epichloë in England". Mycologia. 85 (3): 444–455. doi:10.1080/00275514.1993.12026295. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë brachyelytri

Schardl & Leuchtm. |

North America | Observed | Present | Brachyelytrum erectum | Schardl, Christopher L.; Leuchtmann, Adrian (1999). "Three new species of Epichloë symbiotic with North American grasses". Mycologia. 91 (1): 95–107. doi:10.1080/00275514.1999.12060996. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë bromicola

Leuchtm. & Schardl |

Europe, Asia | Observed on Bromus erectus, Elymus repens and Roegneria kamoji | Present in Bromus benekenii, Bromus ramosus and Hordelymus europaeus, Hordeum brevisubulatum, Leymus chinensis and Roegneria kamoji; absent in Bromus erectus and Elymus repens | Europe: Bromus benekenii, Bromus erectus, Bromus ramosus, Elymus repens, Hordelymus europaeus, Hordeum brevisubulatum. Asia: Leymus chinensis, Roegneria kamoji | Leuchtmann, Adrian; Schardl, Christopher L. (1998). "Mating compatibility and phylogenetic relationships among two new species of Epichloë and other congeneric European species". Mycological Research. 102 (10): 1169–1182. doi:10.1017/S0953756298006236. ISSN 0953-7562. |

| Epichloë elymi

Schardl & Leuchtm. |

North America | Observed | Present | Bromus kalmii, Elymus spp. (including Elymus patula) | Schardl, Christopher L.; Leuchtmann, Adrian (1999). "Three new species of Epichloë symbiotic with North American grasses". Mycologia. 91 (1): 95–107. doi:10.1080/00275514.1999.12060996. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë festucae

Leuchtm., Schardl & M.R. Siegel |

Europe, Asia, North America | Observed | Present | Festuca spp., Koeleria spp., Schedonorus spp. | Leuchtmann, Adrian; Schardl, Christopher L.; Siegel, Malcolm R. (1994). "Sexual compatibility and taxonomy of a new species of Epichloë symbiotic with fine fescue grasses". Mycologia. 86 (6): 802–812. doi:10.1080/00275514.1994.12026487. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë festucae var. lolii

(Latch, M.J. Chr. & Samuels) C.W. Bacon & Schardl |

Europe, Asia, North Africa, introduced in New Zealand, Australia and elsewhere | Not observed | Present | Lolium perenne subsp. perenne | Latch, G.C.M.; Christensen, M.J.; Samuels, G.J. (1984). "Five endophytes of Lolium and Festuca in New Zealand". Mycotaxon. 20: 535–550. |

| Epichloë gansuensis

(C.J. Li & Nan) Schardl |

Asia | Not observed | Present | Achnatherum inebrians, Achnatherum sibiricum, Achnatherum pekinense | Li, C.J.; Nan, Z.B.; Paul, V.H.; Dapprich, P.D.; Liu, Y. (2004). "A new Neotyphodium species symbiotic with drunken horse grass (Achnatherum inebrians) in China". Mycotaxon. 90: 141–147. |

| Epichloë gansuensis var. inebrians

(C.D. Moon & Schardl) Schardl |

Asia | Not observed | Present | Achnatherum inebrians | Moon, Christina D.; Guillaumin, Jean-Jacques; Ravel, Catherine; Li, Chunjie; Craven, Kelly D.; Schardl, Christopher L. (2007). "New Neotyphodium endophyte species from the grass tribes Stipeae and Meliceae". Mycologia. 99 (6): 895–905. doi:10.1080/15572536.2007.11832521. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë glyceriae

Schardl & Leuchtm. |

North America | Observed | Absent | Glyceria spp. | Schardl, Christopher L.; Leuchtmann, Adrian (1999). "Three new species of Epichloë symbiotic with North American grasses". Mycologia. 91 (1): 95–107. doi:10.1080/00275514.1999.12060996. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë mollis

(Morgan-Jones & W. Gams) Leuchtm. & Schardl |

Europe | Observed | Present | Holcus mollis | Morgan-Jones, G.; Gams, W. (1982). "Notes on hyphomycetes. XLI. An endophyte of Festuca arundinacea and the anamorph of Epichloë typhina, new taxa in one of two new sections of Acremonium". Mycotaxon. 15: 311–318. ISSN 0093-4666. |

| Epichloë sibirica

(X. Zhang & Y.B. Gao) Tadych |

Asia | Not observed | Present | Achnatherum sibiricum | Zhang, Xin; Ren, An-Zhi; Wei, Yu-Kun; Lin, Feng; Li, Chuan; Liu, Zhi-Jian; Gao, Yu-Bao (2009). "Taxonomy, diversity and origins of symbiotic endophytes of Achnatherum sibiricum in the Inner Mongolia Steppe of China". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 301 (1): 12–20. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01789.x. ISSN 0378-1097. |

| Epichloë stromatolonga

(Y.L. Ji, L.H. Zhan & Z.W. Wang) Leuchtm. |

Asia | Not observed | Present | Calamagrostis epigejos | Ji, Yan-ling; Zhan, Li-hui; Kang, Yan; Sun, Xiang-hui; Yu, Han-shou; Wang, Zhi-wei (2009). "A new stromata-producing Neotyphodium species symbiotic with clonal grass Calamagrostis epigeios (L.) Roth. grown in China". Mycologia. 101 (2): 200–205. doi:10.3852/08-044. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë sylvatica

Leuchtm. & Schardl |

Europe, Asia | Observed | Present | Brachypodium sylvaticum, Hordelymus europaeus | Leuchtmann, Adrian; Schardl, Christopher L. (1998). "Mating compatibility and phylogenetic relationships among two new species of Epichloë and other congeneric European species". Mycological Research. 102 (10): 1169–1182. doi:10.1017/S0953756298006236. ISSN 0953-7562. |

| Epichloë sylvatica subsp. pollinensis

Leuchtm. & M. Oberhofer |

Europe | Observed | Present | Hordelymus europaeus | Leuchtmann, Adrian; Oberhofer, Martina (2013). "The Epichloë endophytes associated with the woodland grass Hordelymus europaeus including four new taxa". Mycologia. 105 (5): 1315–1324. doi:10.3852/12-400. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë typhina

(Pers.) Tul. & C. Tul. |

Europe, introduced in North America and elsewhere | Observed | Present in Puccinellia distans; absent in other hosts | Anthoxanthum odoratum, Brachypodium phoenicoides, Brachypodium pinnatum, Dactylis glomerata, Lolium perenne, Milium effusum, Phleum pratense, Poa trivialis, Poa silvicola, Puccinellia distans | Tulasne, L.R.; Tulasne, C. (1865). "Nectriei-Phacidiei-Pezizei". Selecta Fungorum Carpologia. 3. Imperial: Paris: 24. |

| Epichloë typhina subsp. clarkii

(J.F. White) Leuchtm. & Schardl |

Europe | Observed | Absent | Holcus lanatus | White, James F. (1993). "Endophyte-host associations in grasses. XIX. A systematic study of some sympatric species of Epichloë in England". Mycologia. 85 (3): 444–455. doi:10.1080/00275514.1993.12026295. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë typhina subsp. poae

(Tadych, K.V. Ambrose, F.C. Belanger & J.F. White) Tadych |

Europe, North America | Observed on Poa nemoralis and Poa pratensis | Present in Poa nemoralis, Poa secunda subsp. juncifolia; absent in Poa pratensis | Europe: Poa nemoralis, Poa pratensis. North America: Poa secunda subsp. juncifolia, Poa sylvestris | Tadych, Mariusz; Ambrose, Karen V.; Bergen, Marshall S.; Belanger, Faith C.; White, James F. (2012). "Taxonomic placement of Epichloë poae sp. nov. and horizontal dissemination to seedlings via conidia". Fungal Diversity. 54 (1): 117–131. doi:10.1007/s13225-012-0170-0. ISSN 1560-2745. |

| Epichloë typhina subsp. poae var. aonikenkana

Iannone & Schardl |

Argentina (Santa Cruz) | Not observed | Present | Bromus setifolius | Mc Cargo, Patricia D.; Iannone, Leopoldo J.; Vignale, María Victoria; Schardl, Christopher L.; Rossi, María Susana (2017). "Species diversity of Epichloë symbiotic with two grasses from southern Argentinean Patagonia". Mycologia. 106 (2): 339–352. doi:10.3852/106.2.339. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë typhina subsp. poae var. canariensis

(C.D. Moon, B. Scott, & M.J. Chr.) Leuchtm. |

Canary Islands | Not observed | Present | Lolium edwardii | Moon, Christina D.; Scott, Barry; Schardl, Christopher L.; Christensen, Michael J. (2000). "The evolutionary origins of Epichloë endophytes from annual ryegrasses". Mycologia. 92 (6): 1103–1118. doi:10.1080/00275514.2000.12061258. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë typhina subsp. poae var. huerfana

(J.F. White, G.T. Cole & Morgan-Jones) Tadych & Leuchtm. |

North America | Not observed | Present | Festuca arizonica | Glenn, Anthony E.; Bacon, Charles W.; Price, Robert; Hanlin, Richard T. (1996). "Molecular phylogeny of Acremonium and its taxonomic implications". Mycologia. 88 (3): 369–383. doi:10.1080/00275514.1996.12026664. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Hybrid Taxa | Progenitor Species | Known Distribution | Sexual Reproduction | Vertical Transmission | Known Host Range | Reference to Species Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epichloë alsodes

T. Shymanovich, C.A. Young, N.D. Charlton & S.H. Faeth |

Epichloë amarillans × Epichloë typhina subsp. poae | North America | Not observed | Present | Poa alsodes | Shymanovich, Tatsiana; Charlton, Nikki D.; Musso, Ashleigh M.; Scheerer, Jonathan; Cech, Nadja B.; Faeth, Stanley H.; Young, Carolyn A. (2017). "Interspecific and intraspecific hybrid Epichloë species symbiotic with the North American native grass Poa alsodes". Mycologia. 109 (3): 459–474. doi:10.1080/00275514.2017.1340779. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë australiensis

(C.D. Moon & Schardl) Leuchtm. & Schardl |

Epichloë festucae × Epichloë typhina complex (from Poa pratensis) | Australia | Not observed | Present | Echinopogon ovatus | Moon, Christina D.; Miles, Christopher O.; Järlfors, Ulla; Schardl, Christopher L. (2017). "The evolutionary origins of three new Neotyphodium endophyte species from grasses indigenous to the Southern Hemisphere". Mycologia. 94 (4): 694–711. doi:10.1080/15572536.2003.11833197. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë cabralii

Iannone, M.S. Rossi & Schardl |

Epichloë amarillans × Epichloë typhina complex (from Poa nemoralis) | Argentina (Santa Cruz, Tierra del Fuego) | Not observed | Present | Phleum alpinum | Mc Cargo, Patricia D.; Iannone, Leopoldo J.; Vignale, María Victoria; Schardl, Christopher L.; Rossi, María Susana (2017). "Species diversity of Epichloë symbiotic with two grasses from southern Argentinean Patagonia". Mycologia. 106 (2): 339–352. doi:10.3852/106.2.339. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë canadensis

N.D. Charlton & C.A. Young |

Epichloë amarillans × Epichloë elymi | North America | Not observed | Present | Elymus canadensis | Charlton, N. D.; Craven, K. D.; Mittal, S.; Hopkins, A. A.; Young, C. A. (2012). "Epichloë canadensis, a new interspecific epichloid hybrid symbiotic with Canada wildrye (Elymus canadensis)". Mycologia. 104 (5): 1187–1199. doi:10.3852/11-403. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë chisosa

(J.F. White & Morgan-Jones) Schardl |

Epichloë amarillans × Epichloë bromicola × Epichloë typhina complex (from Poa pratensis) | North America | Not observed | Present | Achnatherum eminens | Glenn, Anthony E.; Bacon, Charles W.; Price, Robert; Hanlin, Richard T. (2018). "Molecular phylogeny of Acremonium and its taxonomic implications". Mycologia. 88 (3): 369–383. doi:10.1080/00275514.1996.12026664. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë coenophiala

(Morgan-Jones & W. Gams) C.W. Bacon & Schardl |

Epichloë baconii (Lolium associated clade) × Epichloë festucae × Epichloë typhina complex (from Poa nemoralis) | Europe, North Africa, introduced in North America and elsewhere | Not observed | Present | Schedonorus arundinaceus [synonyms: Festuca arundinacea, Lolium arundinaceum] | Morgan-Jones, G.; Gams, W. (1982). "Notes on hyphomycetes. XLI. An endophyte of Festuca arundinacea and the anamorph of Epichloë typhina, new taxa in one of two new sections of Acremonium". Mycotaxon. 15: 311–318. ISSN 0093-4666. |

| Epichloë danica

Leuchtm. & M. Oberhofer |

Epichloë bromicola × Epichloë sylvatica | Europe | Not observed | Present | Hordelymus europaeus | Leuchtmann, Adrian; Oberhofer, Martina (2017). "The Epichloë endophytes associated with the woodland grass Hordelymus europaeus including four new taxa". Mycologia. 105 (5): 1315–1324. doi:10.3852/12-400. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë disjuncta

Leuchtm. & M. Oberhofer |

'Epichloë typhina complex × second unknown ancestor | Europe | Not observed | Present | Hordelymus europaeus | Leuchtmann, Adrian; Oberhofer, Martina (2017). "The Epichloë endophytes associated with the woodland grass Hordelymus europaeus including four new taxa". Mycologia. 105 (5): 1315–1324. doi:10.3852/12-400. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë funkii

(K.D. Craven & Schardl) J.F. White |

Epichloë elymi × Epichloë festucae | North America | Not observed | Present | Achnatherum robustum | Moon, Christina D.; Guillaumin, Jean-Jacques; Ravel, Catherine; Li, Chunjie; Craven, Kelly D.; Schardl, Christopher L. (2017). "New Neotyphodium endophyte species from the grass tribes Stipeae and Meliceae". Mycologia. 99 (6): 895–905. doi:10.1080/15572536.2007.11832521. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë guerinii

(Guillaumin, Ravel & C.D. Moon) Leuchtm. & Schardl |

Epichloë gansuensis × Epichloë typhina complex | Europe | Not observed | Present | Melica ciliata, Melica transsilvanica | Moon, Christina D.; Guillaumin, Jean-Jacques; Ravel, Catherine; Li, Chunjie; Craven, Kelly D.; Schardl, Christopher L. (2017). "New Neotyphodium endophyte species from the grass tribes Stipeae and Meliceae". Mycologia. 99 (6): 895–905. doi:10.1080/15572536.2007.11832521. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë hordelymi

Leuchtm. & M. Oberhofer |

Epichloë bromicola × Epichloë typhina complex | Europe | Not observed | Present | Hordelymus europaeus | Leuchtmann, Adrian; Oberhofer, Martina (2017). "The Epichloë endophytes associated with the woodland grass Hordelymus europaeus including four new taxa". Mycologia. 105 (5): 1315–1324. doi:10.3852/12-400. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë hybrida

M.P. Cox & M.A. Campell |

Epichloë festucae var. lolii × Epichloë typhina | Europe | Not observed | Present | Lolium perenne | Campbell, Matthew A.; Tapper, Brian A.; Simpson, Wayne R.; Johnson, Richard D.; Mace, Wade; Ram, Arvina; Lukito, Yonathan; Dupont, Pierre-Yves; Johnson, Linda J.; Scott, D. Barry; Ganley, Austen R. D.; Cox, Murray P. (2017). "Epichloë hybrida, sp. nov., an emerging model system for investigating fungal allopolyploidy". Mycologia. 109: 1–15. doi:10.1080/00275514.2017.1406174. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë liyangensis

Z.W. Wang, Y. Kang & H. Miao |

Epichloë bromicola × Epichloë typhina complex (from Poa nemoralis) | Asia | Observed | Present | Poa pratensis subsp. pratensis | Yan, Kang; Yanling, Ji; Kunran, Zhu; Hui, Wang; Huimin, Miao; Zhiwei, Wang (2017). "A new Epichloë species with interspecific hybrid origins from Poa pratensis ssp. pratensis in Liyang, China". Mycologia. 103 (6): 1341–1350. doi:10.3852/10-352. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë melicicola

(C.D. Moon & Schardl) Schardl |

Epichloë aotearoae × Epichloë festucae | South Africa | Not observed | Present | Melica racemosa, Melica decumbens | Moon, Christina D.; Miles, Christopher O.; Järlfors, Ulla; Schardl, Christopher L. (2017). "The evolutionary origins of three new Neotyphodium endophyte species from grasses indigenous to the Southern Hemisphere". Mycologia. 94 (4): 694–711. doi:10.1080/15572536.2003.11833197. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë novae-zelandiae

Leuchtm. & A.V. Stewart |

Epichloë amarillans × Epichloë bromicola × Epichloë typhina subsp. poae | New Zealand | Not observed | Present | Poa matthewsii | Leuchtmann, Adrian; Young, Carolyn A.; Stewart, Alan V.; Simpson, Wayne R.; Hume, David E.; Scott, Barry (2019). "Epichloë novae-zelandiae, a new endophyte from the endemic New Zealand grass Poa matthewsii". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 57 (4): 271–288. doi:10.1080/0028825X.2019.1651344. ISSN 0028-825X. |

| Epichloë occultans

(C.D. Moon, B. Scott & M.J. Chr.) Schardl |

Epichloë baconii (Lolium associated clade) × Epichloë bromicola | Europe, North Africa, introduced in New Zealand and elsewhere | Not observed | Present | Lolium multiflorum, Lolium rigidum u.a. | Moon, Christina D.; Scott, Barry; Schardl, Christopher L.; Christensen, Michael J. (2019). "The evolutionary origins of Epichloë endophytes from annual ryegrasses". Mycologia. 92 (6): 1103–1118. doi:10.1080/00275514.2000.12061258. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë pampeana

(Iannone & Cabral) Iannone & Schardl |

Epichloë festucae × Epichloë typhina complex (from Poa nemoralis) | South America | Not observed | Present | Bromus auleticus | Iannone, Leopoldo Javier; Cabral, Daniel; Schardl, Christopher Lewis; Rossi, María Susana (2017). "Phylogenetic divergence, morphological and physiological differences distinguish a new Neotyphodium endophyte species in the grass Bromus auleticus from South America". Mycologia. 101 (3): 340–351. doi:10.3852/08-156. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë schardlii

(Ghimire, Rudgers & K.D. Craven) Leuchtm. |

Epichloë typhina complex (subsp. poae × subsp. poae) | North America | Not observed | Present | Cinna arundinacea | Ghimire, Sita R.; Rudgers, Jennifer A.; Charlton, Nikki D.; Young, Carolyn; Craven, Kelly D. (2017). "Prevalence of an intraspecific Neotyphodium hybrid in natural populations of stout wood reed (Cinna arundinacea L.) from eastern North America". Mycologia. 103 (1): 75–84. doi:10.3852/10-154. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë schardlii var. pennsylvanica

T. Shymanovich, C.A. Young, N.D. Charlton & S.H. Faeth |

Epichloë typhina complex (subsp. poae × subsp. poae) | North America | Not observed | Present | Poa alsodes | Shymanovich, Tatsiana; Charlton, Nikki D.; Musso, Ashleigh M.; Scheerer, Jonathan; Cech, Nadja B.; Faeth, Stanley H.; Young, Carolyn A. (2017). "Interspecific and intraspecific hybrid Epichloë species symbiotic with the North American native grass Poa alsodes". Mycologia. 109 (3): 459–474. doi:10.1080/00275514.2017.1340779. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë siegelii

(K.D. Craven, Leuchtm. & Schardl) Leuchtm. & Schardl |

Epichloë bromicola × Epichloë festucae | Europe | Not observed | Present | Schedonorus pratensis (synonyms: Festuca pratensis, Lolium pratense) | Craven, K.D.; Blankenship, J.D.; Leuchtmann, A.; Hinight, K.; Schardl, C.L. (2001). "Hybrid fungal endophytes symbiotic with the grass Lolium pratense". Sydowia. 53: 44–73. |

| Epichloë sinica

(Z.W. Wang, Y.L. Ji & Y. Kang) Leuchtm. |

Epichloë bromicola × Epichloë typhina complex | Asia | Not observed | Present | Roegneria spp. | Yan, Kang; Yanling, Ji; Xianghui, Sun; Lihui, Zhan; Wei, Li; Hanshou, Yu; Zhiwei, Wang (2017). "Taxonomy of Neotyphodium endophytes of Chinese native Roegneria plants". Mycologia. 101 (2): 211–219. doi:10.3852/08-018. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë sinofestucae

(Y.G. Chen, Y.L. Ji & Z.W. Wang) Leuchtm. |

Epichloë bromicola × Epichloë typhina complex | Asia | Not observed | Present | Festuca parvigluma | Chen, Yong-gan; Ji, Yan-ling; Yu, Han-shou; Wang, Zhi-wei (2017). "A new Neotyphodium species from Festuca parvigluma Steud. grown in China". Mycologia. 101 (5): 681–685. doi:10.3852/08-181. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë tembladerae

(Cabral & J.F. White) Iannone & Schardl |

Epichloë festucae × Epichloë typhina complex (from Poa nemoralis) | North America | Not observed | Present | North America: Festuca arizonica. South America: Bromus auleticus, Bromus setifolius, Festuca argentina, Festuca hieronymi, Festuca magellanica, Festuca superba, Melica stuckertii, Phleum alpinum, Phleum commutatum, Poa huecu, Poa rigidifolia | Cabral, Daniel; Cafaro, Matías J.; Saidman, B.; Lugo, M.; Reddy, Ponaka V.; White, James F. (2019). "Evidence supporting the occurrence of a new species of endophyte in some South American grasses". Mycologia. 91 (2): 315–325. doi:10.1080/00275514.1999.12061021. ISSN 0027-5514. |

| Epichloë uncinata

(W. Gams, Petrini & D. Schmidt) Leuchtm. & Schardl |

Epichloë bromicola × Epichloë typhina complex | Europe | Not observed | Present | Schedonorus pratensis (synonyms: Festuca pratensis, Lolium pratense) | Gams, W.; Petrini, O. J.; Schmidt, D. (1990). "Acremonium uncinatum, a new endophyte in Festuca pratensis". Mycotaxon. 37: 67–71.A1:G25 |

Life cycle and growth

Epichloë species are specialized to form and maintain systemic, constitutive (long-term) symbioses with plants, often with limited or no disease incurred on the host.[8] The best-studied of these symbionts are associated with the grasses and sedges, in which they infect the leaves and other aerial tissues by growing between the plant cells (endophytic growth) or on the surface above or beneath the cuticle (epiphytic growth). An individual infected plant will generally bear only a single genetic individual clavicipitaceous symbiont, so the plant-fungus system constitutes a genetic unit called a symbiotum (pl. symbiota).

Symptoms and signs of the fungal infection, if manifested at all, only occur on a specific tissue or site of the host tiller, where the fungal stroma or sclerotium emerges. The stroma (pl. stromata) is a mycelial cushion that gives rise first to asexual spores (conidia), then to the sexual fruiting bodies (ascocarps; perithecia). Sclerotia are hard resting structures that later (after incubation on the ground) germinate to form stipate stromata. Depending on the fungus species, the host tissues on which stromata or sclerotia are produced may be young inflorescences and surrounding leaves, individual florets, nodes, or small segments of the leaves. Young stromata are hyaline (colorless), and as they mature they turn dark gray, black, or yellow-orange. Mature stromata eject meiotically derived spores (ascospores), which are ejected into the atmosphere and initiate new plant infections (horizontal transmission). In some cases no stroma or sclerotium is produced, but the fungus infects seeds produced by the infected plant, and is thereby transmitted vertically to the next host generation. Most Epichloë species, and all asexual species, can vertically transmit.

The taxonomic dichotomy is especially interesting in this group of symbionts, because vegetative propagation of fungal mycelium occurs by vertical transmission, i.e., fungal growth into newly developing host tillers (=individual grass plants). Importantly, many Epichloë species infect new grass plants solely by growing into the seeds of their grass hosts, and infecting the growing seedling.[9][10] Manifestation of the sexual state — which only occurs in Epichloë species — causes "choke disease", a condition in which grass inflorescences are engulfed by rapid fungal outgrowth forming a stroma. The fungal stroma suppresses host seed production and culminates in the ejection of meiospores (ascospores) that mediate horizontal (contagious) transmission of the fungus to new plants.[9] So, the two transmission modes exclude each other, although in many grass-Epichloë symbiota the fungus actually displays both transmission modes simultaneously, by choking some tillers and transmitting in seeds produced by unchoked tillers.

While being obligate symbionts in nature, most epichloae are readily culturable in the laboratory on culture media such as potato dextrose agar or a minimal salts broth supplemented with thiamine, sugars or sugar alcohols, and organic nitrogen or ammonium.[11]

Epichloë species are commonly spread by flies of the genus Botanophila. The flies lay their eggs in the growing fungal tissues and the larvae feed on them.[12]

Evolution

The epichloae display a number of central features that suggest a very strong and ancient association with their grass hosts. The symbiosis appears to have existed already during the early grass evolution that has spawned today's pooid grasses. This is suggested by phylogenetic studies indicating a preponderance of codivergence of Epichloë species with the grass hosts they inhabit.[13] Growth of the fungal symbiont is very tightly regulated within its grass host, indicated by a largely unbranched mycelial morphology and remarkable synchrony of grass leaf and hyphal extension of the fungus;[14][15] the latter seems to occur via a mechanism that involves stretch-induced or intercalary elongation of the endophyte's hyphae, a process so far not found in any other fungal species, indicating specialized adaptation of the fungus to the dynamic growth environment inside its host.[16] A complex NADPH oxidase enzyme-based ROS-generating system in Epichloë species is indispensable for maintenance of this growth synchrony. Thus, it has been demonstrated that deletion of genes encoding these enzymes in Epichloë festucae causes severely disordered fungal growth in grass tissues and even death of the grass plant.[17][18]

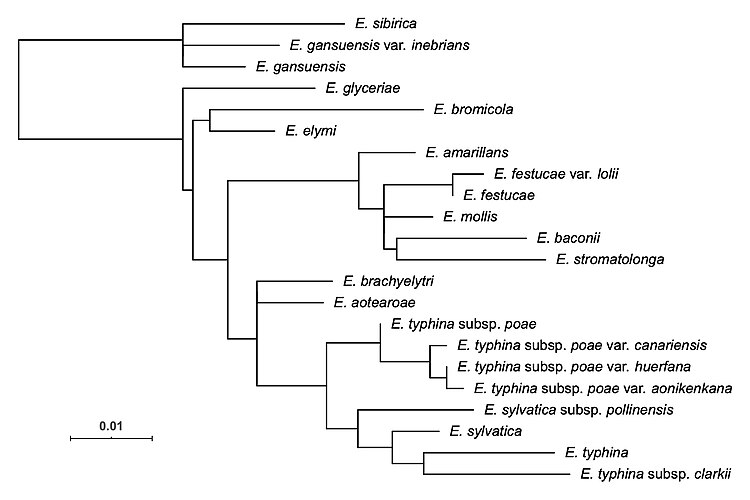

Molecular phylogenetic evidence demonstrates that asexual Epichloë species are derived either from sexual Epichloë species, or more commonly, are hybrids of two or more progenitor Epichloë species.[19][20]

Bioactive compounds

Many Epichloë endophytes produce a diverse range of natural product compounds with biological activities against a broad range of herbivores.[21][22] The purpose of these compounds is as a toxicity or feeding deterrence against insect and mammalian herbivores.[23] Ergoline alkaloids (which are ergot alkaloids, named after the ergot fungus, Claviceps purpurea, a close relative of the epichloae) are characterized by a ring system derived from 4-prenyl tryptophan.[24] Among the most abundant ergot alkaloids in epichloë-symbiotic grasses is ergovaline, comprising an ergoline moiety attached to a bicyclic tripeptide containing the amino acids L-proline, L-alanine, and L-valine. Key genes and enzymes for ergot alkaloid biosynthesis have been identified in epichloae and include dmaW, encoding dimethylallyl-tryptophan synthase and lpsA, a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase.[24]

Another group of epichloë alkaloids are the indole-diterpenoids, such as lolitrem B, which are produced from the activity of several enzymes, including prenyltransferases and various monooxygenases.[25] Both the ergoline and indole-diterpenoid alkaloids have biological activity against mammalian herbivores, and also activity against some insects.[21] Peramine is a pyrrolopyrazine alkaloid thought to be biosynthesized from the guanidinium-group-containing amino acid L-arginine, and pyrrolidine-5-carboxylate, a precursor of L-proline,[26] and is an insect-feeding deterrent. The loline alkaloids[27] are 1-aminopyrrolizidines with an oxygen atom linking bridgehead carbons 2 and 7, and are biosynthesized from the amino acids L-proline and L-homoserine.[28] The lolines have insecticidal and insect-deterrent activities comparable to nicotine.[27] Loline accumulation is strongly induced in young growing tissues[29] or by damage to the plant-fungus symbiotum.[30] Many, but not all, epichloae produce up to three classes of these alkaloids in various combinations and amounts.[21] Recently it has been shown that Epichloë uncinata infection and loline content afford Festulolium grasses protection from black beetle (Heteronychus arator).[31]

Many species in Epichloë produce biologically active alkaloids, such as ergot alkaloids, indole-diterpenoids (e.g., lolitrem B), loline alkaloids, and the unusual guanidinium alkaloid, peramine.[21]

Ecology

Effects on the grass plant

It has been proposed that vertically transmitted symbionts should evolve to be mutualists since their reproductive fitness is intimately tied to that of their hosts.[32] In fact, some positive effects of epichloae on their host plants include increased growth, drought tolerance, and herbivore and pathogen resistance.[9][33] Resistance against herbivores has been attributed to alkaloids produced by the symbiotic epichloae.[21] Although grass-epichloë symbioses have been widely recognized to be mutualistic in many wild and cultivated grasses, the interactions can be highly variable and sometimes antagonistic, especially under nutrient-poor conditions in the soil.[34]

Ecosystem dynamics

Due to the relatively large number of grass species harboring epichloae and the variety of environments in which they occur, the mechanisms underlying beneficial or antagonistic outcomes of epichloë-grass symbioses are difficult to delineate in natural and also agricultural environments.[9][35] Some studies suggest a relationship between grazing by herbivores and increased epichloë infestation of the grasses on which they feed,[36][37] whereas others indicate a complex interplay between plant species and fungal symbionts in response to herbivory or environmental conditions.[38] The strong anti-herbivore activities of several bioactive compounds produced by the epichloae [21][26] and relatively modest direct effects of the epichloae on plant growth and physiology[39][40] suggest that these compounds play a major role in the persistence of the symbiosis.

References

- ^ a b Fries, E.M. (1849). Summa vegetabilium Scandinaviae (in Latin). Stockholm, Leipzig: Bonnier. p. 572.

- ^ Persoon, C.H. (1798). Icones et Descriptiones Fungorum Minus Cognitorum (in Latin). Leipzig: Bibliopolii Breitkopf-Haerteliani impensis.

- ^ Tulasne, L.R.; Tulasne, C. (1865). Selecta Fungorum Carpologia: Nectriei – Phacidiei – Pezizei (in Latin). Vol. 3.

- ^ a b c d Leuchtmann, A.; Bacon, C. W.; Schardl, C. L.; White, J. F.; Tadych, M. (2014). "Nomenclatural realignment of Neotyphodium species with genus Epichloë" (PDF). Mycologia. 106 (2): 202–215. doi:10.3852/13-251. ISSN 0027-5514. PMID 24459125. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-07. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- ^ White, J.F.; Reddy, P.V. (1998). "Examination of Structure and Molecular Phylogenetic Relationships of Some Graminicolous Symbionts in Genera Epichloe and Parepichloe". Mycologia. 90 (2): 226. doi:10.2307/3761298. ISSN 0027-5514. JSTOR 3761298.

- ^ Morgan-Jones, G.; Gams, W. (1982). "Notes on hyphomycetes. XLI. An endophyte of Festuca arundinacea and the anamorph of Epichloe typhina, new taxa in one of two new sections of Acremonium". Mycotaxon. 15: 311–318. ISSN 0093-4666.

- ^ Glenn AE, Bacon CW, Price R, Hanlin RT (1996). "Molecular phylogeny of Acremonium and its taxonomic implications" (PDF). Mycologia. 88 (3): 369–383. doi:10.2307/3760878. JSTOR 3760878.

- ^ Spatafora JW, Sung GH, Sung JM, Hywel-Jones NL, White JF Jr (2007). "Phylogenetic evidence for an animal pathogen origin of ergot and the grass endophytes". Mol. Ecol. 16 (8): 1701–1711. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03225.x. PMID 17402984.

- ^ a b c d Schardl CL, Leuchtmann A, Spiering MJ (2004). "Symbioses of grasses with seedborne fungal endophytes". Annu Rev Plant Biol. 55: 315–340. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141735. PMID 15377223.

- ^ Freeman EM (1904). "The seed fungus of Lolium temulentum L., the darnel". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 196 (214–224): 1–27. doi:10.1098/rstb.1904.0001.

- ^ Blankenship JD, Spiering MJ, Wilkinson HH, Fannin FF, Bush LP, Schardl CL (2001). "Production of loline alkaloids by the grass endophyte, Neotyphodium uncinatum, in defined media". Phytochemistry. 58 (3): 395–401. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00272-2. PMID 11557071.

- ^ Górzyńska, K.; et al. (2010). "An unusual Botanophila–Epichloë association in a population of orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata) in Poland". Journal of Natural History. 44 (45–46): 2817–24. doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.2006.00518.x.

- ^ Schardl CL, Craven KD, Speakman S, Stromberg A, Lindstrom A, Yoshida R (2008). "A novel test for host-symbiont codivergence indicates ancient origin of fungal endophytes in grasses". Syst. Biol. 57 (3): 483–498. arXiv:q-bio/0611084. doi:10.1080/10635150802172184. PMID 18570040.

- ^ Tan YY, Spiering MJ, Scott V, Lane GA, Christensen MJ, Schmid J (2001). "In planta regulation of extension of an endophytic fungus and maintenance of high metabolic rates in its mycelium in the absence of apical extension". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 (12): 5377–5383. doi:10.1128/AEM.67.12.5377-5383.2001. PMC 93319. PMID 11722882.

- ^ Christensen MJ, Bennett RJ, Schmid J (2002). "Growth of Epichloë/Neotyphodium and p-endophytes in leaves of Lolium and Festuca grasses". Mycol. Res. 96: 93–106. doi:10.1017/S095375620100510X.

- ^ Christensen MJ, Bennett RJ, Ansari HA, Koga H, Johnson RD, Bryan GT, Simpson WR, Koolaard JP, Nickless EM, Voisey CR (2008). "Epichloë endophytes grow by intercalary hyphal extension in elongating grass leaves". Fungal Genet. Biol. 45 (2): 84–93. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2007.07.013. PMID 17919950.

- ^ Tanaka A, Christensen MJ, Takemoto D, Park P, Scott B (2006). "Reactive oxygen species play a role in regulating a fungus-perennial ryegrass mutualistic interaction". Plant Cell. 18 (4): 1052–1066. doi:10.1105/tpc.105.039263. PMC 1425850. PMID 16517760.

- ^ Takemoto D, Tanaka A, Scott B (2006). "A p67Phox-like regulator is recruited to control hyphal branching in a fungal-grass mutualistic symbiosis". Plant Cell. 18 (10): 2807–2821. doi:10.1105/tpc.106.046169. PMC 1626622. PMID 17041146.

- ^ Tsai HF, Liu JS, Staben C, Christensen MJ, Latch GC, Siegel MR, Schardl CL (1994). "Evolutionary diversification of fungal endophytes of tall fescue grass by hybridization with Epichloë species". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91 (7): 2542–2546. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.2542T. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.7.2542. PMC 43405. PMID 8172623.

- ^ Moon CD, Craven KD, Leuchtmann A, Clement SL, Schardl CL (2004). "Prevalence of interspecific hybrids amongst asexual fungal endophytes of grasses". Mol Ecol. 13 (6): 1455–1467. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02138.x. PMID 15140090.

- ^ a b c d e f Bush LP, Wilkinson HH, Schardl CL (1997). "Bioprotective Alkaloids of Grass-Fungal Endophyte Symbioses". Plant Physiol. 114 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1104/pp.114.1.1. PMC 158272. PMID 12223685.

- ^ Scott B (2001). "Epichloë endophytes: fungal symbionts of grasses". Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4 (4): 393–398. doi:10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00224-1. PMID 11495800.

- ^ Roberts CA, West CP, Spiers DE, eds (2005). Neotyphodium in Cool-Season Grasses. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-8138-0189-6.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Schardl CL, Panaccione DG, Tudzynski P (2006). Ergot alkaloids – biology and molecular biology. Vol. 63. pp. 45–86. doi:10.1016/S1099-4831(06)63002-2. ISBN 9780124695634. PMID 17133714.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Young CA, Felitti S, Shields K, Spangenberg G, Johnson RD, Bryan GT, Saikia S, Scott B (2006). "A complex gene cluster for indole-diterpene biosynthesis in the grass endophyte Neotyphodium lolii". Fungal Genet Biol. 43 (10): 679–693. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2006.04.004. PMID 16765617.

- ^ a b Tanaka A, Tapper BA; Popay A, Parker; EJ, Scott B (2005). "A symbiosis expressed non-ribosomal peptide synthetase from a mutualistic fungal endophyte of perennial ryegrass confers protection to the symbiotum from insect herbivory". Mol. Microbiol. 57 (4): 1036–1050. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04747.x. PMID 16091042.

- ^ a b Schardl CL, Grossman RB, Nagabhyru P, Faulkner JR, Mallik UP (2007). "Loline alkaloids: currencies of mutualism". Phytochemistry. 68 (7): 980–996. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.01.010. PMID 17346759.

- ^ Blankenship JD, Houseknecht JB, Pal S, Bush LP, Grossman RB, Schardl CL (2005). "Biosynthetic precursors of fungal pyrrolizidines, the loline alkaloids". ChemBioChem. 6 (6): 1016–1022. doi:10.1002/cbic.200400327. PMID 15861432.

- ^ Zhang, DX, Nagabhyru, P, Schardl CL (2009). "Regulation of a chemical defense against herbivory produced by symbiotic fungi in grass plants". Plant Physiology. 150 (2): 1072–1082. doi:10.1104/pp.109.138222. PMC 2689992. PMID 19403726.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gonthier DJ, Sullivan TJ, Brown KL, Wurtzel B, Lawal R, VandenOever K, Buchan Z, Bultman TL (2008). "Stroma-forming endophyte Epichloe glyceriae provides wound-inducible herbivore resistance to its grass host". Oikos. 117 (4): 629–633. doi:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2008.16483.x.

- ^ Barker GM; Patchett BJ; Cameron NE (2014). "Epichloë uncinata infection and loline content afford Festulolium grasses protection from black beetle (Heteronychus arator). Landcare Research, Hamilton, New Zealand & Cropmark Seeds Ltd, Christchurch, New Zealand 20 Dec 2014". New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research. 58: 35–56. doi:10.1080/00288233.2014.978480.

- ^ Ewald PW (1987). "Transmission modes and evolution of the parasitism-mutualism continuum". Ann NY Acad Sci. 503 (1): 295–306. Bibcode:1987NYASA.503..295E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb40616.x. PMID 3304078.

- ^ Malinowski DP, Belesky DP (2000). "Adaptations of endophyte-infected cool-season grasses to environmental stresses: mechanisms of drought and mineral stress tolerance". Crop Sci. 40 (4): 923–940. doi:10.2135/cropsci2000.404923x.

- ^ Saikkonen K, Ion D, Gyllenberg M (2002). "The persistence of vertically transmitted fungi in grass metapopulations". Proc Biol Sci. 269 (1498): 1397–1403. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2006. PMC 1691040. PMID 12079664.

- ^ Saikkonen K, Lehtonen P, Helander M, Koricheva J, Faeth SH (2006). "Model systems in ecology: dissecting the endophyte-grass literature". Trends Plant Sci. 11 (9): 428–433. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2006.07.001. PMID 16890473.

- ^ Clay K, Holah J, Rudgers JA (2005). "Herbivores cause a rapid increase in hereditary symbiosis and alter plant community composition". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102 (35): 12465–12470. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10212465C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503059102. PMC 1194913. PMID 16116093.

- ^ Kohn S, Hik DS (2007). "Herbivory mediates grass-endophyte relationships". Ecology. 88 (11): 2752–2757. doi:10.1890/06-1958.1. PMID 18051643.

- ^ Granath G, Vicari M, Bazely DR, Ball JP, Puentes A, Rakocevic T (2007). "Variation in the abundance of fungal endophytes in fescue grasses along altitudinal and grazing gradients". Ecography. 3 (3): 422–430. doi:10.1111/j.0906-7590.2007.05027.x.

- ^ Hahn H, McManus MT, Warnstorff K, Monahan BJ, Young CA, Davies E, Tapper BA, Scott, B (2007). "Neotyphodium fungal endophytes confer physiological protection to perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) subjected to a water deficit". Env. Exp. Bot. 63 (1–3): 183–199. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.10.021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hunt MG.; Rasmussen S; Newton PCD; Parsons AJ; Newman JA (2005). "Near-term impacts of elevated CO2, nitrogen and fungal endophyte-infection on Lolium perenne L. growth, chemical composition and alkaloid production". Plant Cell Environ. 28 (11): 1345–1354. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01367.x.