Abstract factory pattern: Difference between revisions

remove pseudocode, since the Python example serves as well Tag: section blanking |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

class Button(ABC): |

class Button(ABC): |

||

@abstractmethod |

@abstractmethod |

||

def paint(self): |

def paint(self): |

||

| Line 89: | Line 88: | ||

class LinuxButton(Button): |

class LinuxButton(Button): |

||

def paint(self): |

def paint(self): |

||

return 'Render a button in a Linux style' |

return 'Render a button in a Linux style' |

||

| Line 95: | Line 93: | ||

class WindowsButton(Button): |

class WindowsButton(Button): |

||

def paint(self): |

def paint(self): |

||

return 'Render a button in a Windows style' |

return 'Render a button in a Windows style' |

||

| Line 101: | Line 98: | ||

class MacOSButton(Button): |

class MacOSButton(Button): |

||

def paint(self): |

def paint(self): |

||

return 'Render a button in a MacOS style' |

return 'Render a button in a MacOS style' |

||

| Line 107: | Line 103: | ||

class GUIFactory(ABC): |

class GUIFactory(ABC): |

||

@abstractmethod |

@abstractmethod |

||

def create_button(self): |

def create_button(self): |

||

| Line 114: | Line 109: | ||

class LinuxFactory(GUIFactory): |

class LinuxFactory(GUIFactory): |

||

def create_button(self): |

def create_button(self): |

||

return LinuxButton() |

return LinuxButton() |

||

| Line 120: | Line 114: | ||

class WindowsFactory(GUIFactory): |

class WindowsFactory(GUIFactory): |

||

def create_button(self): |

def create_button(self): |

||

return WindowsButton() |

return WindowsButton() |

||

| Line 126: | Line 119: | ||

class MacOSFactory(GUIFactory): |

class MacOSFactory(GUIFactory): |

||

def create_button(self): |

def create_button(self): |

||

return MacOSButton() |

return MacOSButton() |

||

| Line 155: | Line 147: | ||

class Button(ABC): |

class Button(ABC): |

||

@abstractmethod |

@abstractmethod |

||

def paint(self): |

def paint(self): |

||

| Line 167: | Line 158: | ||

class WindowsButton(Button): |

class WindowsButton(Button): |

||

def paint(self): |

def paint(self): |

||

return 'Render a button in a Windows style' |

return 'Render a button in a Windows style' |

||

| Line 173: | Line 163: | ||

class MacOSButton(Button): |

class MacOSButton(Button): |

||

def paint(self): |

def paint(self): |

||

return 'Render a button in a MacOS style' |

return 'Render a button in a MacOS style' |

||

| Line 193: | Line 182: | ||

print(result) |

print(result) |

||

</syntaxhighlight> |

</syntaxhighlight> |

||

<!-- |

|||

Please note that Wikipedia:WikiProject_Computer_science/Manual_of_style discourages multiple |

|||

source code implementations and recommends Python as a language designed for readability. |

|||

--> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

* [[Concrete class]] |

* [[Concrete class]] |

||

Revision as of 18:29, 24 July 2020

The abstract factory pattern provides a way to encapsulate a group of individual factories that have a common theme without specifying their concrete classes.[1] In normal usage, the client software creates a concrete implementation of the abstract factory and then uses the generic interface of the factory to create the concrete objects that are part of the theme. The client does not know (or care) which concrete objects it gets from each of these internal factories, since it uses only the generic interfaces of their products.[1] This pattern separates the details of implementation of a set of objects from their general usage and relies on object composition, as object creation is implemented in methods exposed in the factory interface.[2]

An example of this would be an abstract factory class DocumentCreator that provides interfaces to create a number of products (e.g. createLetter() and createResume()). The system would have any number of derived concrete versions of the DocumentCreator class like FancyDocumentCreator or ModernDocumentCreator, each with a different implementation of createLetter() and createResume() that would create a corresponding object like FancyLetter or ModernResume. Each of these products is derived from a simple abstract class like Letter or Resume of which the client is aware. The client code would get an appropriate instance of the DocumentCreator and call its factory methods. Each of the resulting objects would be created from the same DocumentCreator implementation and would share a common theme (they would all be fancy or modern objects). The client would only need to know how to handle the abstract Letter or Resume class, not the specific version that it got from the concrete factory.

A factory is the location of a concrete class in the code at which objects are constructed. The intent in employing the pattern is to insulate the creation of objects from their usage and to create families of related objects without having to depend on their concrete classes.[2] This allows for new derived types to be introduced with no change to the code that uses the base class.

Use of this pattern makes it possible to interchange concrete implementations without changing the code that uses them, even at runtime. However, employment of this pattern, as with similar design patterns, may result in unnecessary complexity and extra work in the initial writing of code. Additionally, higher levels of separation and abstraction can result in systems that are more difficult to debug and maintain.

Overview

The Abstract Factory [3] design pattern is one of the twenty-three well-known GoF design patterns that describe how to solve recurring design problems to design flexible and reusable object-oriented software, that is, objects that are easier to implement, change, test, and reuse.

The Abstract Factory design pattern solves problems like: [4]

- How can an application be independent of how its objects are created?

- How can a class be independent of how the objects it requires are created?

- How can families of related or dependent objects be created?

Creating objects directly within the class that requires the objects is inflexible because it commits the class to particular objects and makes it impossible to change the instantiation later independently from (without having to change) the class. It stops the class from being reusable if other objects are required, and it makes the class hard to test because real objects cannot be replaced with mock objects.

The Abstract Factory design pattern describes how to solve such problems:

- Encapsulate object creation in a separate (factory) object. That is, define an interface (AbstractFactory) for creating objects, and implement the interface.

- A class delegates object creation to a factory object instead of creating objects directly.

This makes a class independent of how its objects are created (which concrete classes are instantiated). A class can be configured with a factory object, which it uses to create objects, and even more, the factory object can be exchanged at run-time.

Definition

The essence of the Abstract Factory Pattern is to "Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes.".[5]

Usage

The factory determines the actual concrete type of object to be created, and it is here that the object is actually created (in C++, for instance, by the new operator). However, the factory only returns an abstract pointer to the created concrete object.

This insulates client code from object creation by having clients ask a factory object to create an object of the desired abstract type and to return an abstract pointer to the object.[6]

As the factory only returns an abstract pointer, the client code (that requested the object from the factory) does not know — and is not burdened by — the actual concrete type of the object that was just created. However, the type of a concrete object (and hence a concrete factory) is known by the abstract factory; for instance, the factory may read it from a configuration file. The client has no need to specify the type, since it has already been specified in the configuration file. In particular, this means:

- The client code has no knowledge whatsoever of the concrete type, not needing to include any header files or class declarations related to it. The client code deals only with the abstract type. Objects of a concrete type are indeed created by the factory, but the client code accesses such objects only through their abstract interface.[7]

- Adding new concrete types is done by modifying the client code to use a different factory, a modification that is typically one line in one file. The different factory then creates objects of a different concrete type, but still returns a pointer of the same abstract type as before — thus insulating the client code from change. This is significantly easier than modifying the client code to instantiate a new type, which would require changing every location in the code where a new object is created (as well as making sure that all such code locations also have knowledge of the new concrete type, by including for instance a concrete class header file). If all factory objects are stored globally in a singleton object, and all client code goes through the singleton to access the proper factory for object creation, then changing factories is as easy as changing the singleton object.[7]

Structure

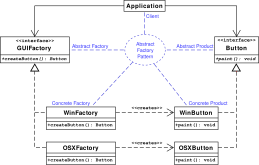

UML diagram

![A sample UML class and sequence diagram for the Abstract Factory design pattern. [8]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/a/aa/W3sDesign_Abstract_Factory_Design_Pattern_UML.jpg)

In the above UML class diagram,

the Client class that requires ProductA and ProductB objects does not instantiate the ProductA1 and ProductB1 classes directly.

Instead, the Client refers to the AbstractFactory interface for creating objects,

which makes the Client independent of how the objects are created (which concrete classes are instantiated).

The Factory1 class implements the AbstractFactory interface by instantiating the ProductA1 and ProductB1 classes.

The UML sequence diagram shows the run-time interactions:

The Client object calls createProductA() on the Factory1 object, which creates and returns a ProductA1 object.

Thereafter,

the Client calls createProductB() on Factory1, which creates and returns a ProductB1 object.

Lepus3 chart

Python example

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from sys import platform

class Button(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def paint(self):

pass

class LinuxButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return 'Render a button in a Linux style'

class WindowsButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return 'Render a button in a Windows style'

class MacOSButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return 'Render a button in a MacOS style'

class GUIFactory(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def create_button(self):

pass

class LinuxFactory(GUIFactory):

def create_button(self):

return LinuxButton()

class WindowsFactory(GUIFactory):

def create_button(self):

return WindowsButton()

class MacOSFactory(GUIFactory):

def create_button(self):

return MacOSButton()

if platform == 'linux':

factory = LinuxFactory()

elif platform == 'darwin':

factory = MacOSFactory()

elif platform == 'win32':

factory = WindowsFactory()

else:

raise NotImplementedError(

f'Not implemented for your platform: {platform}'

)

button = factory.create_button()

result = button.paint()

print(result)

Alternative implementation using the classes themselves as factories:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from sys import platform

class Button(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def paint(self):

pass

class LinuxButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return 'Render a button in a Linux style'

class WindowsButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return 'Render a button in a Windows style'

class MacOSButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return 'Render a button in a MacOS style'

if platform == "linux":

factory = LinuxButton

elif platform == "darwin":

factory = MacOSButton

elif platform == "win32":

factory = WindowsButton

else:

raise NotImplementedError(

f'Not implemented for your platform: {platform}'

)

button = factory()

result = button.paint()

print(result)

See also

References

- ^ a b Freeman, Eric; Robson, Elisabeth; Sierra, Kathy; Bates, Bert (2004). Hendrickson, Mike; Loukides, Mike (eds.). Head First Design Patterns (paperback). Vol. 1. O'REILLY. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-596-00712-6. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ^ a b Freeman, Eric; Robson, Elisabeth; Sierra, Kathy; Bates, Bert (2004). Hendrickson, Mike; Loukides, Mike (eds.). Head First Design Patterns (paperback). Vol. 1. O'REILLY. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-596-00712-6. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ^ Erich Gamma; Richard Helm; Ralph Johnson; John Vlissides (1994). Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. Addison Wesley. pp. 87ff. ISBN 0-201-63361-2.

- ^ "The Abstract Factory design pattern - Problem, Solution, and Applicability". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- ^ Gamma, Erich; Richard Helm; Ralph Johnson; John M. Vlissides (2009-10-23). "Design Patterns: Abstract Factory". informIT. Archived from the original on 2009-10-23. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

Object Creational: Abstract Factory: Intent: Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes.

- ^ Veeneman, David (2009-10-23). "Object Design for the Perplexed". The Code Project. Archived from the original on 2011-09-18. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

The factory insulates the client from changes to the product or how it is created, and it can provide this insulation across objects derived from very different abstract interfaces.

- ^ a b "Abstract Factory: Implementation". OODesign.com. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- ^ "The Abstract Factory design pattern - Structure and Collaboration". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

External links

- Abstract Factory implementation in Java

Media related to Abstract factory at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Abstract factory at Wikimedia Commons- Abstract Factory UML diagram + formal specification in LePUS3 and Class-Z (a Design Description Language)

- Abstract Factory Abstract Factory implementation example