European enslavement of Indigenous Americans: Difference between revisions

GreenC bot (talk | contribs) Reformat 2 archive links. Wayback Medic 2.5 |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

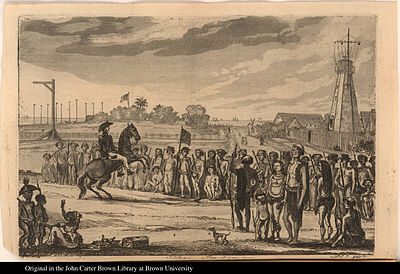

[[File:Plate 10 The Indians.jpg|thumb|400px|Illustration of the [[Demerara rebellion of 1823]], an insurrection of the African slaves in the colony of [[Demerara]], in Guyana. African women and children stand near a group of [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Indigenous Americans]] carrying sticks form a semi-circle around a European officer.]] |

[[File:Plate 10 The Indians.jpg|thumb|400px|Illustration of the [[Demerara rebellion of 1823]], an insurrection of the African slaves in the colony of [[Demerara]], in Guyana. African women and children stand near a group of [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Indigenous Americans]] carrying sticks form a semi-circle around a European officer.]] |

||

'''[[Slavery]] among the indigenous peoples of [[North America|North]] and [[South America]]''' took many forms. After the |

'''[[Slavery]] among the indigenous peoples of [[North America|North]] and [[South America]]''' took many forms. After [[European colonization of the Americas|first European settlers arrived]], five Native American tribes came to own black slaves, imitating the Europeans.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=McLoughlin|first=William G.|date=1974-01-01|title=Red Indians, Black Slavery and White Racism: America's Slaveholding Indians|jstor=2711653|journal=American Quarterly|volume=26|issue=4|pages=367–385|doi=10.2307/2711653}}</ref> |

||

European colonies purchased indigenous people as slaves as part of the international indigenous American [[History of slavery|slave trade]], which lasted from the late 15th century into the 19th century. Recently, scholars [[Andrés Reséndez]] and Brett Rushforth have estimated that between two and five million indigenous people were enslaved as part of this trade.<ref>Rushforth estimates "between two and four million Indian slaves." {{Cite book|title=Bonds of alliance: Indigenous and Atlantic slaveries in New France.|last=Rushforth|first=Brett|date=2014|publisher=Univ Of North Carolina Pr|year=|isbn=978-1-4696-1386-4|location=Place of publication not identified|pages=9}}</ref><ref>Reséndez estimates between 2.462 and 4.985 million indigenous people were enslaved. {{Cite book|title=The other slavery: The uncovered story of Indian enslavement in America|last=Reséndez|first=Andrés|date=2017|publisher=|year=|isbn=978-0-544-94710-8|location=|pages=324}}</ref> |

European colonies purchased indigenous people as slaves as part of the international indigenous American [[History of slavery|slave trade]], which lasted from the late 15th century into the 19th century. Recently, scholars [[Andrés Reséndez]] and Brett Rushforth have estimated that between two and five million indigenous people were enslaved as part of this trade.<ref>Rushforth estimates "between two and four million Indian slaves." {{Cite book|title=Bonds of alliance: Indigenous and Atlantic slaveries in New France.|last=Rushforth|first=Brett|date=2014|publisher=Univ Of North Carolina Pr|year=|isbn=978-1-4696-1386-4|location=Place of publication not identified|pages=9}}</ref><ref>Reséndez estimates between 2.462 and 4.985 million indigenous people were enslaved. {{Cite book|title=The other slavery: The uncovered story of Indian enslavement in America|last=Reséndez|first=Andrés|date=2017|publisher=|year=|isbn=978-0-544-94710-8|location=|pages=324}}</ref> |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

Employers in Mexico, forbidden to take or use slaves, turned to [[Debt bondage|debt peonage]], advancing money to workers on terms that were impossible to meet. Laws were passed requiring servants to complete the terms of any contract for service.<ref>"In the absence of slavery, the only way for Mexicans to bind workers to their properties and businesses was by extending credit to them. As a result, debt peonage proliferated throughout Mexico (and in the American Southwest after slavery was abolished there in the 1860s) and emerged as the principal mechanism of the other slavery" Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 238). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.</ref><ref>“We do not consider that we own our laborers; we consider they are in debt to us,” Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 239). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.</ref> |

Employers in Mexico, forbidden to take or use slaves, turned to [[Debt bondage|debt peonage]], advancing money to workers on terms that were impossible to meet. Laws were passed requiring servants to complete the terms of any contract for service.<ref>"In the absence of slavery, the only way for Mexicans to bind workers to their properties and businesses was by extending credit to them. As a result, debt peonage proliferated throughout Mexico (and in the American Southwest after slavery was abolished there in the 1860s) and emerged as the principal mechanism of the other slavery" Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 238). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.</ref><ref>“We do not consider that we own our laborers; we consider they are in debt to us,” Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 239). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.</ref> |

||

== |

==United States== |

||

The territories acquired from Mexico by the United States had a system of indigenous slavery and laws which supported it. Congress passed a resolution on March 3, 1865 creating the Joint Special Committee on the Condition of the Indian Tribes.<ref>Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 298). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.</ref> After extensive investigations in the West it issued [[Condition of the Indian Tribes|The Doolittle Report]] of 1867: ''Condition of the Indian Tribes: Report of the Joint Special Committee Appointed Under Joint Resolution of March 3, 1865.'' The chairman of the committee was Senator [[James Rood Doolittle]], U.S. Senator from Wisconsin. "The report substantiated the traffic of Indian slaves and the prevalence of peonage."<ref name="Reséndez, Andrés p. 299">Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 299). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.</ref> On June 9, 1865, at the urging of [[James Harlan (senator)|James Harlan]], [[United States Secretary of the Interior|Secretary of the Interior]], President [[Andrew Johnson]] issued a directive, "...that the authority of the Executive branch of the Government should be exercised for the effectual suppression of a practice which is alike in violation of the rights of the Indians and the provisions of the organic law of said Territory."<ref name="Reséndez, Andrés p. 299"/> The [[Bureau of Indian Affairs|Commissioner of Indian Affairs]] was ordered to investigate the situation in New Mexico. He selected Julius K. Graves as "special agent". Graves arrived in Santa Fe December 30, 1865 and began his investigation by attending the opening of the territorial legislature. He found that both debt peonage and slavery of Indian captives were institutions of long standing in New Mexico with many influential Hispanics and Federal officials holding slaves. He pleaded for effective action.<ref>Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 299-301). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.</ref> |

The territories acquired from Mexico by the United States had a system of indigenous slavery and laws which supported it. Congress passed a resolution on March 3, 1865 creating the Joint Special Committee on the Condition of the Indian Tribes.<ref>Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 298). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.</ref> After extensive investigations in the West it issued [[Condition of the Indian Tribes|The Doolittle Report]] of 1867: ''Condition of the Indian Tribes: Report of the Joint Special Committee Appointed Under Joint Resolution of March 3, 1865.'' The chairman of the committee was Senator [[James Rood Doolittle]], U.S. Senator from Wisconsin. "The report substantiated the traffic of Indian slaves and the prevalence of peonage."<ref name="Reséndez, Andrés p. 299">Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 299). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.</ref> On June 9, 1865, at the urging of [[James Harlan (senator)|James Harlan]], [[United States Secretary of the Interior|Secretary of the Interior]], President [[Andrew Johnson]] issued a directive, "...that the authority of the Executive branch of the Government should be exercised for the effectual suppression of a practice which is alike in violation of the rights of the Indians and the provisions of the organic law of said Territory."<ref name="Reséndez, Andrés p. 299"/> The [[Bureau of Indian Affairs|Commissioner of Indian Affairs]] was ordered to investigate the situation in New Mexico. He selected Julius K. Graves as "special agent". Graves arrived in Santa Fe December 30, 1865 and began his investigation by attending the opening of the territorial legislature. He found that both debt peonage and slavery of Indian captives were institutions of long standing in New Mexico with many influential Hispanics and Federal officials holding slaves. He pleaded for effective action.<ref>Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 299-301). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:09, 2 September 2020

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

This section for: Mexico, New Mexico, California, Utah, Colorado relies largely or entirely on a single source. (October 2019) |

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (August 2010) |

Slavery among the indigenous peoples of North and South America took many forms. After first European settlers arrived, five Native American tribes came to own black slaves, imitating the Europeans.[1]

European colonies purchased indigenous people as slaves as part of the international indigenous American slave trade, which lasted from the late 15th century into the 19th century. Recently, scholars Andrés Reséndez and Brett Rushforth have estimated that between two and five million indigenous people were enslaved as part of this trade.[2][3]

European enslavement of Indigenous people

The encomienda system was an agreement between the Council of the Indies and the Spanish crown to exchange education and protection from warring for the use of the land owned by the caciques, lords, or encomenderos and the promise of seasonal labour.[4] Intermittently, the colonists needed to purge these anaborios (native mercenaries). From the earliest days on the Caribbean islands they settled, the Spanish encomenderos precipitated many revolts and hostilities, both Native American and Spanish in origin, through their harsh treatment. One of the first localities for intensive use of encomienda was the gold mines of Hispaniola.

Native American slavery was also practiced by the English in the Carolinas who sold Native American captives into slavery locally and on the English plantations in the Caribbean.[5] One of the first tribes that specialized in slave raids and trade with Carolina was the Westo, followed by many others including the Yamasee, Chickasaw, and Creek. Historian Alan Gallay estimates the number of Native Americans in southeast America sold in the British slave trade from 1670 to 1715 as between 24,000 and 51,000. He also notes that during this period more slaves (Native American, African, or otherwise) were exported from Charles Town than imported.[6] Slaving of Indians in Carolinas had been forbidden in about 1672.[7]

Slavery of Native Americans was organized in colonial and Mexican California through Franciscan missions, theoretically entitled to ten years of Native labor, but in practice maintaining them in perpetual servitude, until their charge was revoked in the mid-1830s. Following the 1848 American invasion, Native Californians were enslaved in the new state from statehood in 1850 to 1867.[8] Slavery required the posting of a bond by the slave holder and enslavement occurred through raids and four months' servitude imposed as a punishment for Native American "vagrancy".[9]

The citizens of New France received slaves as gifts from their allies among First Nations peoples. Many of these slaves were prisoners taken in raids against the villages of the Fox nation, a tribe that was an ancient rival of the Miami people and their Algonquian allies.[10] Native or panis, (likely a corruption of Pawnee) slaves were much easier to obtain and thus more numerous than African slaves in New France, but were less valued. The average native slave died at 18, whereas the average African slave died at 25.[11] In 1790, the abolition movement was gaining credence in Canada; there was an incident involving a slave woman being violently abused by her slave owner on her way to being sold in the United States.[12] The Act Against Slavery of 1793 legislated the gradual abolition of slavery: no slaves could be imported; slaves already in the province would remain enslaved until death, no new slaves could be brought into Upper Canada, and children born to female slaves would be slaves but must be freed at age 25.[12] The Act remained in force until 1833 when the British Parliament's Slavery Abolition Act finally abolished slavery in all parts of the British Empire.[13] Historian Marcel Trudel has discovered 4,092 recorded slaves throughout Canadian history, of which 2,692 were aboriginal people, owned mostly by the French, and 1,400 blacks owned mostly by the British, together owned by about 1,400 masters.[12] Trudel also noted 31 marriages took place between French colonists and aboriginal slaves.[12]

Plantations

Prior to mass settlement by their own people in the New World colonies such as English Carolina, Spanish Florida, and French Louisiana in what is now the southern United States had a plantation economy where slaves, mostly indigenous, worked on plantations.[14] An extensive slave trade participated in by Indians themselves provided labor, affected all tribes in the area, and was at the center of the economy of the region.[15][16]

Spain

Slavery of Native Americans was illegal in Spain or Spanish territories. However, slavery in other contexts as an institution still existed in Spain itself, particularly Ottoman and Barbary prisoners and Muslim rebels from southern Spain following the Reconquista. The enthusiasm of Columbus for the slave trade was rejected by Isabella and Ferdinand, the Spanish monarchs.[17] A decree issued in 1500 by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella specifically forbade enslavement of natives, but there were three exceptions which were freely used by colonial Spanish authorities to evade the prohibition: cannibals (Caribs, one target population, practiced ceremonial cannibalism); those taken in "just wars"; and slaves purchased from other indigenous people.[18] The need for slave labor first arose in the placer gold deposits of Cibao on Hispaniola. After the natives of Hispaniola were worked to death using the encomienda system, the other islands of the Caribbean were scoured for slaves. A shortage of labor resulting from a smallpox epidemic in 1518 resulted in an intensified search.[19] By 1521 the islands of the northern Caribbean, such as the Bahamas inhabited by the peaceful Taíno people, were for the most part depopulated.[20] The pearl fisheries on the coast of Venezuela was another activity which had a high attrition rate.[21]

In 1542, urged on by Friar Bartolomé de Las Casas, author of A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies,[22] Charles I of Spain enacted the New Laws. By its terms it declared Indians free vassals, but, in practical terms, only made it more difficult to own and exploit slaves. Despite being technically illegal, slavery continued in Spanish America for centuries.[23] On one hand the courts were instructed to "put special care in the good treatment and conservation of the Indians", to remain informed of any abuses committed against Indians, and "to act quickly and without delaying maliciously as has happened in the past";[24] on the other hand, "... Spanish masters resorted to slight changes in terminology, gray areas, and subtle reinterpretations to continue to hold Indians in bondage."[25]

Gregorio López, one of the supporters of the New Laws, was appointed to the Council of the Indies in 1543 and undertook attempts to free the Indian slaves of Seville.[26] Over 100 cases of Indians seeking freedom, not all successfully,[27] are in the legal archives of Seville.[28] Masters often contested attempts by slaves to obtain freedom; the cases could drag on for years, meanwhile, the slaves had nowhere to go and often remained in the service of their master and sometimes faced mistreatment.[27] The use of Indian slaves in Spain itself died out by the early 17th century.[29]

In Mexico, Peru, and other parts of Spanish America indigenous slaves were much more important economically and beneficiaries of the system were much more resilient and resourceful; indigenous slavery continued for centuries.[30][31] In Peru, the Spanish emissary sent to enforce the New Laws was murdered and beheaded.[32] In Mexico, the Spanish emissary, Francisco Tello de Sandoval, a member of the Spanish Inquisition and the Council of the Indies, agreed to suspend the laws and appeal to the King. Some concessions were made, the encomiendas were expanded, but the basic law was not modified.[33]

Spanish movement north after discovery of vast deposits of silver[34] in the desert regions north of the conquered Aztec Empire resulted in wars with the unconquered tribes of that region. The first, the Mixtón War, was a serious struggle, but the Spanish prevailed with the help of tens of thousands of Aztec allies. The second, the Chichimeca War, did not go well. Spanish troops were over-matched by vast numbers of naked native warriors using obsidian tipped arrows, and the treasury was exhausted by the struggle, and in the end troops were withdrawn and a peace program was employed. In both instances the exception of "just war" was employed to take thousands of slaves.[35] Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva, first governor of the New Kingdom of León, played a prominent role in the slave trade.[36] The silver deposits of Mexico were massive and were exploited for centuries by underground mining of hundreds of rich veins.

In Peru thousands of indigent workers were drafted to work in the silver mines of Potosí, Huancavelica, and Cailloma, a system that continued for 250 years.[37]

According to Andrés Reséndez, author of The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America, slaving which provided labor to the silver mines of northern Mexico was a major cause of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and other unrest among the Indians of northern Mexico.[38] Following the reconquest of New Mexico the business of providing slaves for the New Mexico market passed into the hands of the Navajo, Utes, Comanches, and Apaches who had acquired horses (in part from the herds abandoned by the Spanish in 1680) and thus mobility.[39]

In the early 18th century the market for slaves in the silver mines began to dry up and a surplus of slaves, and ex-slaves, began to build up in New Mexico. Called Genízaros, these descendants of Pawnees, Jumanos, Apaches, and Kiowas and other plains Indians once taken as slaves by the Comanches and others became distinct communities in New Mexico.[40]

Spanish Florida

Settlement at Saint Augustine in 1565 was followed by establishment of missions in what is now northern Florida and the coast of Georgia.[41]

Chile

In Chile Spanish occupation of the lands of the Mapuche was vigorously contested for 3 centuries in the Arauco War. The prescription against enslaving Indians was lifted by in 1608 Philip III of Spain[42] for Mapuches caught in war.[43] Mapuches "rebels" were considered Christian apostates and could therefore be enslaved according to the church teachings of the day.[44] In reality these legal changes only formalized Mapuche slavery that was already occurring at the time, with captured Mapuches being treated as property in the way that they were bought and sold among the Spanish. Legalisation made Spanish slave raiding increasingly common in the Arauco War.[43] Mapuche slaves were exported north to places such as La Serena and Lima in Peru.[45] Spanish slave raiding was an underlying cause of the large Mapuche uprising of 1655.[46]

Philip III of Spain successor Philip IV of Spain changed course in the latter part of his reign and began restricting Mapuche slavery.[47] Philip IV died without freeing the indigenous slaves of Chile but his wife Mariana of Austria, serving as regent, and his son Charles II of Spain engaged in a broad anti-slavery campaign throughout the Spanish Empire.[48][49]

The anti-slavery campaign began with an order by Mariana of Austria in 1667 freeing all the Indian slaves in Peru that had been captured in Chile.[50] Her order was met with disbelief and dismay in Peru.[51] Without exception she freed the Indian slaves of Mexico in 1672.[52] After receiving a plea from the Pope she freed the slaves of the southern Andes.[53] On June 12, 1679 Charles II issued a general declaration freeing all indigenous slaves in Spanish America. In 1680 this was included in the Recopilación de las leyes de Indias, a codification of the laws of Spanish America.[54] The Caribes, "cannibals," were the only exception.[55] Governor Juan Enríquez of Chile resisted strongly, writing protests to the king and not publishing the decrees freeing Indian slaves.[56] The royal anti-slavery crusade did not end indigenous slavery in Spain's American possessions, but, in addition to resulting in the freeing of thousands of slaves, it ended the involvement and facilitation by government officials of slaving by the Spanish; purchase of slaves remained possible but only from indigenous slaver such as the Caribs of Venezuela or the Comanches.[57][58]

Mexico

After Mexico's independence in 1821, it did not abolish black slavery until 1829 when a hero of the insurgency, Vicente Guerrero, "el Negrito," was president. At independence, racial and caste (casta) categories were abolished.[59] However, the revolution had disrupted the defenses at the border, the presidios, and the mining region of northern Mexico. For decades the region was subject to raids by Apaches, Kiowas, and large Comanche war parties who looted, killed and took slaves. The Comanches penetrated far into Mexico, raiding as late as the 1870s. The main object was horses, but goods and slaves, in the thousands, were also taken.[60] In time a significant fraction of the slaving tribes came to consist of Mexicans and Mexican Indians, up to half of the Comanches.[61] Bent's Fort, a trading post on the Santa Fe Trail, was one customer of the slavers[62] as were Comancheros, Hispanic traders based in New Mexico who regularly traded with the Comanche and other tribes who engaged in raids into Mexico.[63] Some border communities in Mexico itself were also in the market.[64]

Employers in Mexico, forbidden to take or use slaves, turned to debt peonage, advancing money to workers on terms that were impossible to meet. Laws were passed requiring servants to complete the terms of any contract for service.[65][66]

United States

The territories acquired from Mexico by the United States had a system of indigenous slavery and laws which supported it. Congress passed a resolution on March 3, 1865 creating the Joint Special Committee on the Condition of the Indian Tribes.[67] After extensive investigations in the West it issued The Doolittle Report of 1867: Condition of the Indian Tribes: Report of the Joint Special Committee Appointed Under Joint Resolution of March 3, 1865. The chairman of the committee was Senator James Rood Doolittle, U.S. Senator from Wisconsin. "The report substantiated the traffic of Indian slaves and the prevalence of peonage."[68] On June 9, 1865, at the urging of James Harlan, Secretary of the Interior, President Andrew Johnson issued a directive, "...that the authority of the Executive branch of the Government should be exercised for the effectual suppression of a practice which is alike in violation of the rights of the Indians and the provisions of the organic law of said Territory."[68] The Commissioner of Indian Affairs was ordered to investigate the situation in New Mexico. He selected Julius K. Graves as "special agent". Graves arrived in Santa Fe December 30, 1865 and began his investigation by attending the opening of the territorial legislature. He found that both debt peonage and slavery of Indian captives were institutions of long standing in New Mexico with many influential Hispanics and Federal officials holding slaves. He pleaded for effective action.[69]

New Mexico

Debt peonage was well established in New Mexico as Americans assumed governance after the Mexican–American War as well as slaveholding by the Navajo.[70] Indian slaves were in the households of many prominent New Mexicans, including the governor and Kit Carson. Slaves taken during Navajo removal resulted in a substantial increase to a total of several thousand.[71] New Mexico was a territory of the United States; thus the laws implementing and enforcing slavery passed by the territorial legislature were subject to review by the Congress of the United States which, in 1860, voided them.[72] In 1862 the U.S. House of Representatives enacted a broader law prohibiting "slavery and involuntary servitude in any of the Territories of the United States."[73] These actions changed nothing on the ground in New Mexico where active slaving among the Navajo was in progress.[73] The number of slaves taken dropped sharply in the 1870s.[74]

California

The Mexican secularization act of 1833 "freed" the Indians attached to the missions of California, providing for distribution of land to mission Indians and sale of remaining grazing land. Through grants and auctions the bulk of the land was transferred to wealthy Californios and other investors. Any Indians who had received land soon fell into debt peonage and became attached to the new Ranchos. The workforce was supplemented with Indians who had been captured.[75] Immigrating Americans fell into the same pattern with varying degrees of grace; there were no black slaves and importation of Chinese as laborers was in the future.[76][77] The Indian Act of 1850 authorized auctioning of Indians who were not gainfully employed. The Anti-Vagrancy Act, also known as the Greaser Act, was enacted in 1855 in California, to target those of Mexican descent, among others, by legalizing the arrest of those perceived as violating its anti-vagrancy statute. 24,000 to 27,000 California Native Americans were taken as forced laborers by settlers including 4,000 to 7,000 children;[78]

Utah

Soon after the Mormons settled at Salt Lake City they were visited by a band of Utes who insisted on trading two young slaves to them. When the Mormons were reluctant, they killed one child and began torturing the other.[79] The Utes generally slaved among the Paiutes of the Great Basin.[80] The Mormons, on consideration, determined that purchasing slaves was a religious duty (Indians being degraded Israelites whose skin had turned black due to their evil ways)[81] and passed the Act for the relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners in 1852 authorizing holding of purchased slaves for 20 years after purchase.[82] Life among the Mormons was lonely for the Indian slaves. The Mormons declined to breed with them, and they were cut off from their tribes.[83]

Colorado

Scores of Navajo slaves taken by Mexican and Ute slavers during the Long Walk of the Navajo were sold into the new settlements in Costilla and Conejos Counties in what is now Colorado.[84]

Portugal

Brazil

Indigenous slavery in Brazil increased the territorial growth of Portuguese colonies in America.[85]

England

Carolina

The policy of the Proprietors of English Carolina was, "no Indian upon any occasion or pretense whatsoever is to be made a Slave, or without his own consent be carried out of Carolina."[86] Nevertheless, Native American slaves were one of the principle exports of the Province of Carolina to Barbados and other West Indian islands during the 17th Century.[87] It was claimed that slaves purchased from Indian slavers gave consent to work or be transported.[88] The good intentions of the Proprietors, who were also concerned about slaving resulting in conflict with neighboring tribes, were frustrated by the possibilities for profits to colonial traders[89] who build the foundations of substantial fortunes on Indian and African slavery.[90]

It was only in the 1750s that there was substantial migration of subsistence farmers to the Carolinas, prior to that the economy was based on plantations, manned by Indian, then, as more were imported, by African slaves.[91] What set Carolina apart from the other English colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America was not allowing slavery, the other colonies also had some slavery at points in their history when Indian captives were available, but a substantial population of potential slaves in its hinterlands.[92] The superiority of English trade goods over that of the competing French and Spanish played an important role in centralizing trade in Carolina.[93]

France

Louisiana

Indigenous enslavement of indigenous peoples

In Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica the most common forms of slavery were those of prisoners of war and debtors. People unable to pay back a debt could be sentenced to work as a slave to the person owed until the debt was worked off.[citation needed] Slavery was not usually hereditary; children of slaves were born free.

Most victims of human sacrifice were prisoners of war or slaves.[94]

First Nations of Canada routinely captured slaves from neighboring tribes. Slave-owning tribes were Muscogee Creek of Georgia, the Pawnee and Klamath, the Caribs of Dominica, the Tupinambá of Brazil, and some fishing societies, such as the Yurok, that lived along the coast from what is now Alaska to California.[95] The Haida, Nuu-chah-nulth, Tlingit, Coast Tsimshian and some other tribes who lived along the Pacific Northwest Coast were traditionally known as fierce warriors and slave-traders, raiding as far as California and also among neighboring people, particularly the Coast Salish groups. Slavery was hereditary, with new slaves generally being prisoners of war or captured for the purpose of trade and status. Among some Pacific Northwest tribes about a quarter of the population were slaves.[12][96][97]

Indigenous slavers

A few tribes become slavers, capturing large numbers of other indigenous tribes for sale to planters, traders, or other Indians. The Westo, who first sold slaves to the Colony of Virginia, moved south and became the principle ally and slaver of Carolina, until they themselves were exterminated as a tribe and sold into slavery in the West Indies. The "Savannah," a branch of the Shawnee were recruited to fill the role of slavers to the colony.[98] The Comanche, Chiricahua Apache, and Ute engaged in slaving in the American southwest, and Mexico, sometimes taking and selling Mexicans as slaves.

See also

References

- ^ McLoughlin, William G. (1 January 1974). "Red Indians, Black Slavery and White Racism: America's Slaveholding Indians". American Quarterly. 26 (4): 367–385. doi:10.2307/2711653. JSTOR 2711653.

- ^ Rushforth estimates "between two and four million Indian slaves." Rushforth, Brett (2014). Bonds of alliance: Indigenous and Atlantic slaveries in New France. Place of publication not identified: Univ Of North Carolina Pr. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4696-1386-4.

- ^ Reséndez estimates between 2.462 and 4.985 million indigenous people were enslaved. Reséndez, Andrés (2017). The other slavery: The uncovered story of Indian enslavement in America. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-544-94710-8.

- ^ Anghiera Pietro Martire D'. De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 181. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^ "Welcome to Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ Gallay, Alan (2002). The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717. Yale University Press. pp. 298–301. ISBN 0-300-10193-7.

- ^ "Right at the time when the Spanish campaign was gaining momentum in 1671–1672, the lord proprietors of the English Carolina colony ordered that “no Indian upon any occasion or pretense whatsoever is to be made a Slave, or without his own consent be carried out of Carolina.” Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 147). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Castillo, Edward D. (1998). Short Overview of California Indian History Archived 14 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine", California Native American Heritage Commission.

- ^ Beasley, Delilah L. (1918). "Slavery in California," The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 3, No. 1. (Jan.), pp. 33–44.

- ^ Brett Rushforth, "Slavery, the Fox Wars, and the Limits of Alliance" Archived 10 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine William and Mary Quarterly, 63 (January 2005), No.1, para. 32. Rushforth confuses the two Vincennes explorers. François-Marie was 12 years old during the First Fox War.

- ^ Cooper, Afua (2006). The Hanging of Angélique. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-200553-0.

- ^ a b c d e Cooper, Afua. The Untold Story of Canadian Slavery and the Burning of Old Montreal, (Toronto:HarperPerennial, 2006)

- ^ "Slavery Abolition Act 1833; Section LXIV". 28 August 1833. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ^ "From Jamaica to Brazil, the Chesapeake to Saint Domingue, Europeans responded to the international market economy by building slave-based plantations producing staple commodities." Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 181-182). Kindle Edition.

- ^ "The English empire was also able to consume as much of the natives' commodities as the natives could produce, including the trade in Indian slaves. This trade infected the South: it set in motion a gruesome series of wars that engulfed the region. For close to five decades, virtually every group of people in the South lay threatened by destruction in these wars. Huge areas became depopulated, thousands of Indians died, and thousands more were forcibly relocated to new areas in the South or exported from the region."Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 176-179). Kindle Edition.

- ^ Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 204-205). Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Who is this Columbus who dares to give out my vassals as slaves?" Isabella and Ferdinand freed many Indians and, astonishingly, mandated that many of them be returned to the New World. Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 553–554). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 761–766).

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 804–812). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "The attackers literally carried off entire populations, leaving empty islands in their wake." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 726–787).

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 595–597). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 836–838). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 849–856).

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 865–869). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition]]. p. (Kindle Locations 871–875.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 882-887). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ a b Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 998–1006). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "The archives in Seville contain more than a hundred cases of Natives who had the courage to partner with Spanish attorneys and officials to sue their masters." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 892-893). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 1089–1093). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "The Spanish crown also attempted to end Indian slavery in the New World, but the situation could not have been more different there. Indian slaves constituted a major pillar of the societies and economies of the Americas." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 1094-1096). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Thus a new regime emerged in the 1540s and 1550s, a regime in which Indians were legally free but remained enslaved through slight reinterpretations, changes in nomenclature, and practices meant to get around the New Laws." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 1199-1200). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "In Peru a group of colonists murdered the official sent from Spain to enforce the laws and then decapitated him."Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 1187-1188). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "It was a major victory for slave owners. Encomiendas remained in existence for another century and a half, affecting tens of thousands of Indians. Other provisions of the New Laws were not suspended, however, and the crown continued to press for the abolition of Indian slavery in the New World." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 1188-1198). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ The development of silver mines in central and northern Mexico in the 1540s and 1550s had completely transformed the slave trade. Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 1387-1388). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 1507-1526). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "...because Indian slavery was illegal— made sure to exploit loopholes and elicit plenty of official protection. Frontier captains were ideally suited for this line of work, as the empire expanded prodigiously during the sixteenth century. For them, slavery was no sideline to warfare or marginal activity born out of the chaos of conquest. It was first and foremost a business involving investors, soldiers, agents, and powerful officials. Perhaps no one understood this better than Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva,..." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Kindle Locations 1307-1617). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ ...a gargantuan system of draft labor known as the mita, which required that more than two hundred Indian communities spanning a large area in modern-day Peru and Bolivia send one-seventh of their adult population to work in the mines of Potosí, Huancavelica, and Cailloma. In any given year, ten thousand Indians or more had to take their turns working in the mines. This state-directed system began in 1573 and remained in operation for 250 years. Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 124). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 170). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 179). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Such Indians became known as genízaros, a term that conjures thoughts of captivity, servitude, and the merging of Plains, Pueblo, and Hispanic cultural traits. In 1733 a group of one hundred Indians who identified themselves as “los genízaros” wrote to the governor of New Mexico claiming that they were no longer in servitude to any Spaniard and therefore wished to obtain some land. This first list of genízaros reveals the geography of enslavement at the time, as many of the signatories were Indians from the plains, including Pawnees, Jumanos, Apaches, and Kiowas." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 180). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 252-253). Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Philip III, had taken the drastic step of stripping the Mapuche Indians of the customary royal protection against enslavement in 1608, thus making Chile one of the few parts of the empire where slave taking was entirely legal." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 127-128). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ a b Valenzuela Márquez 2009, p. 231–233

- ^ Foerster 1993, p. 21.

- ^ Valenzuela Márquez 2009, pp. 234–236

- ^ Barros Arana 2000, p. 348.

- ^ Philip requested a reassessment of the imperial policies in Chile and expressed his belief that slave taking had become the main obstacle to peace with the Mapuche Indians." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 128). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "...the king died before he could set the Indians of Chile free and discharge his royal conscience. But Philip was not alone in trying to make things right. His wife, Mariana, was thirty years younger than he, every bit as pious, and far more determined. The crusade to free the Indians of Chile, and those in the empire at large, gained momentum during Queen Mariana’s regency, from 1665 to 1675, and culminated in the reign of her son Charles II. Alarmed by reports of large slaving grounds on the periphery of the Spanish empire, they used the power of an absolute monarchy to bring about the immediate liberation of all indigenous slaves. Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 128). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ [They] took on deeply entrenched slaving interests, deprived the empire of much-needed revenue, and risked the very stability of distant provinces to advance their humanitarian agenda. They waged a war against Indian bondage that raged as far as the islands of the Philippines, the forests of Chile, the llanos (grasslands) of Colombia and Venezuela, and the deserts of Chihuahua and New Mexico. Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 128-129). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Queen Mariana brought renewed energy to the abolitionist crusade. If we had to choose an opening salvo, it would be the queen’s 1667 order freeing all Chilean Indians who had been taken to Peru. Her order was published in the plazas of Lima and required all Peruvian slave owners to “turn their Indian slaves loose at the first opportunity.” Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 136). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ When the viceroy of Peru learned of this order, he could not hide his disbelief. Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 136). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ In 1672 she freed the Indian slaves of Mexico, irrespective of their provenance or the circumstances of their enslavement. Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 136). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ [she] waited only a few weeks to respond, banning all forms of slavery in Chile. They extended the same prohibition to the Calchaquí Valleys on the other side of the Andes. The campaign to liberate the Indians had kicked into high gear. Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 136-137). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition

- ^ Finally, on June 12, 1679, he issued a decree of continental scope: “No Indians of my Western Indies, Islands, and Mainland of the Ocean Sea, under any circumstance or pretext can be held as slaves; instead they will be treated as my vassals...." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 137). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ As it turned out, they excluded two groups from their broad royal protection: the inhabitants of the island of Mindanao in the Philippines, “who have taken up the sect of Muhamad and are against our Church and empire,” and the Carib Indians, “who attack our settlements and eat human flesh.” Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 137-138). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 142-144). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "The crusade also had a chilling effect on European slavers. For all of his reluctance to free the slaves, Governor Enríquez of Chile did issue orders prohibiting soldiers from launching slave raids and taking Indian captives after 1676." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 146-147). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 177). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ The newly independent government granted citizenship rights to all Indians living in Mexico and abolished slavery in 1829. Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 219). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 219-230). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "...captives [] were incorporated into their respective bands and came to comprise significant proportions of their overall populations. According to the American ethnographer James Mooney, who spent five years doing fieldwork among the Kiowa Indians in the 1890s, “At least one fourth of the whole number have more or less of captive blood . . . chiefly Mexicans and Mexican Indians, with Indians of other tribes, and several whites taken from Texas when children.” In a census of Comanche families conducted in Oklahoma Territory in 1902, fully forty-five percent turned out to be of Mexican descent." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 225-226). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Bent’s Fort employed more than a hundred individuals, including merchants, teamsters, hunters, herders, and laborers. Many of these employees were Mexicans whom Colonel William Bent had purchased from Comanche and Kiowa Indians." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 226). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 229). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "...some Mexican communities, such as San Carlos, in Chihuahua, were notorious for acquiring the spoils offered by Indians— including captives taken elsewhere in Mexico..." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 230). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "In the absence of slavery, the only way for Mexicans to bind workers to their properties and businesses was by extending credit to them. As a result, debt peonage proliferated throughout Mexico (and in the American Southwest after slavery was abolished there in the 1860s) and emerged as the principal mechanism of the other slavery" Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 238). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ “We do not consider that we own our laborers; we consider they are in debt to us,” Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 239). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 298). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ a b Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 299). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 299-301). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Indian captives in New Mexico were not referred to as “slaves” but as “peons.” Clearly, the shift to debt peonage was well under way there, and the system was highly coercive. According to Calhoun, peons could escape their servitude only by paying a certain amount to their owners. Indeed, the Indian agent likened peonage to chattel slavery: “Peons, you are aware, is but another name for slaves as that term is understood in our Southern States,” he explained in a letter to the commissioner of Indian affairs, adding that the main difference was that the peonage system was not confined to a particular “race of the human family,” but applied to “all colors and tongues.” Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 245-245). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "...by the summer of 1865, nearly all propertied New Mexicans, whether Hispanic or Anglo, held Indian slaves, primarily women and children of the Navajo nation, who were “bought and sold by and between the inhabitants at a price as much as is a horse or an ox.” He estimated that the total number of Indian slaves in New Mexico ranged from fifteen hundred to three thousand, “and the most prevalent opinion seems to be that they considerably exceed two thousand.” Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 294). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ '...a bill “to disapprove and declare null and void all Territorial acts and parts of acts heretofore passed by the Legislative Assembly of New Mexico which establish, protect, or legalize involuntary servitude or slavery within said Territory, except as punishment for crime, upon due conviction.”' Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 297). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ a b Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 297). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "...this evidence shows that Indian slavery diminished in New Mexico, it did not disappear." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 313). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Faced with dwindling resources and loss of land, former mission Indians had little choice but to put themselves under the protection of overlords like the Vallejos. Other Indian laborers had been captured in military campaigns north of Sonoma." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 249). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Through his good fortune and their efforts, Bidwell amassed a fortune in a short time. He was a pragmatist who used his personal rapport with the Indians and his provisions to his advantage. Bidwell paid his workers with food and clothing rather than cash, but to his credit, he did not use debt or coercion to get his way." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 251). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "...although the two American partners may have been unusually (even pathologically) cruel, they were able to enslave these Indians because such activities were common throughout the region and there was a thriving market for Indian slaves." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 262). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Exchange Team, The Jefferson. "NorCal Native Writes Of California Genocide". JPR Jefferson Public Radio. Info is in the podcast. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019.

- ^ "These Indians were just returning from a raiding campaign and had two girls whom they intended to exchange for firearms. The Mormons were initially reluctant to trade....the Utes killed one of the prisoners and began torturing the other, a girl of about seven years of age." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 268). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "The Utes made the ferrying of Paiute Indians from the Great Basin into New Mexico a part of their seasonal movements. Mounted Indians procured slaves in the spring, moved about with them in the summer, and sold them at the New Mexican fairs in the fall, only to repeat the cycle the following year." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 190). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Lamanites were cursed by God, assumed a “dark and loathsome countenance,” and over the centuries grew fierce and warlike. Cut off from the teachings of God, the Lamanites became a degraded people." “The Lord has caused us to come here for this very purpose,” said Orson Pratt, one of the original Mormon “apostles,” in 1855, “that we might accomplish the redemption of these suffering degraded Israelites.” Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 268-270). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 272-273). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Anecdotal evidence illustrates the difficulties Indian women brought up in Mormon households faced in finding marriage partners. Susie Leavitt, for example, had two children out of wedlock. When she was called before the local church authorities to answer for her sins, she famously replied, “I have a right to children. No white man will marry me. I cannot live with the Indians. But I can have children, and I will support the children that I have . . . God meant that a woman should have children.” Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (p. 276). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 292,293). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ E se o tráfico negreiro não houvesse existido?

- ^ Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Location 724). Kindle Edition.

- ^ "The linchpin that facilitated the inward and outward flow were captured Native Americans, a highly valuable commodity modity who could be sold to any European colony." Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 199-202). Kindle Edition.

- ^ Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 720-723). Kindle Edition.

- ^ Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 904-908). Kindle Edition.

- ^ "The Indian Dealers were hell-bent on the exploitation of human resources-African and Amerindian-to make their wealth. Moore and Middleton became scions of two of the colony's most prominent families. Other families, too, would build their fortunes first on Indian slavery, then on African slavery." Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 1000-1001). Kindle Edition.

- ^ South Carolina colonists displayed little interest in pursuing a subsistence existence until the 1750s, when many Europeans of humble backgrounds emigrated to the colony's backcountry. Before then, the colony mostly attracted people preoccupied by the search for exportable portable commodities that others, mainly Indians and Africans, produced. Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 171-173). Kindle Edition.

- ^ "...the opportunity to enslave Indians on a scale not available elsewhere." Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 972-975). Kindle Edition.

- ^ "...English goods enticed interest from many. Much more than the Spanish, the English traded their wares with Indians. Metal tools, guns, alcohol, textiles, and fripperies led numerous Indians to seek out the English..." Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 1028-1030). Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Human sacrifice", Britannica Concise Encyclopedia

- ^ "Welcome to Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "UH - Digital History". Archived from the original on 21 August 2003. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "Civilization.ca - Haida - Haida villages - Warfare". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "The colony's leadership convinced the Savannah to move into the defeated feated Westo's vacated position along the Savannah River and become their chief partner in the enslaving of Amerindians." Professor Alan Gallay. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717 (Kindle Locations 882-883). Kindle Edition.

- Bibliography

- Barros Arana, Diego. Historia general de Chile (in Spanish). Vol. Tomo cuarto (Digital edition based on the second edition of 2000 ed.). Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

- Foerster, Rolf (1993). Introducción a la religiosidad mapuche (in Spanish). Editorial universitaria.

- Valenzuela Márquez, Jaime (2009). "Esclavos mapuches. Para una historia del secuestro y deportación de indígenas en la colonia". In Gaune, Rafael; Lara, Martín (eds.). Historias de racismo y discriminación en Chile (in Spanish).

Further reading

- Brown, Harry J.; Hans Staden Among the Tupinambas

- Carocci, Max; Written Out of History: Contemporary Native American Narratives of Enslavement (2009)

- Gallay, Alan; Forgotten Story of Indian Slavery (2003).

- Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

- "English Trade in Deerskins and Indian Slaves", New Georgia Encyclopedia

External links

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090126040215/http://patrickminges.info/afram/ - Website, Aframerindian Slave Narratives