Boris Godunov (opera): Difference between revisions

m Task 18 (cosmetic): eval 5 templates: hyphenate params (3×); |

m →Roles: note for clairty |

||

| Line 434: | Line 434: | ||

''Note:'' Roles designated with an asterisk (*) do not appear in the 1869 Original Version. 'Yuródivïy' is often translated as 'Simpleton' or 'Idiot'. However, '[[Foolishness for Christ#Eastern Christianity|Holy Fool]]' is a more accurate English equivalent.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://arzamas.academy/materials/1375|title=Чайковский и "Могучая кучка": спор о русской музыке|trans-title=Tchaikovsky and The Mighty Handful: A Debate about Russian Music|quote=Under the influence of these ideas, the source of which was largely French naturalism, new images from the social lower classes emerge in Mussorgsky’s works as “high” music - for example, the [[Foolishness for Christ#Eastern Christianity|Holy Fool]] [often wrongly translated to English as 'Simpleton'] in opera ''Boris Godunov''|publisher=Arzamas Academy|access-date=November 22, 2019|language=ru}} |

''Note:'' Roles designated with an asterisk (*) do not appear in the 1869 Original Version. 'Yuródivïy' is often translated as 'Simpleton' or 'Idiot'. However, '[[Foolishness for Christ#Eastern Christianity|Holy Fool]]' is a more accurate English equivalent.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://arzamas.academy/materials/1375|title=Чайковский и "Могучая кучка": спор о русской музыке|trans-title=Tchaikovsky and The Mighty Handful: A Debate about Russian Music|quote=Under the influence of these ideas, the source of which was largely French naturalism, new images from the social lower classes emerge in Mussorgsky’s works as “high” music - for example, the [[Foolishness for Christ#Eastern Christianity|Holy Fool]] [often wrongly translated to English as 'Simpleton'] in opera ''Boris Godunov''|publisher=Arzamas Academy|access-date=November 22, 2019|language=ru}} |

||

* {{cite web |title=Блаженные похабы |trans-title=The Blessed Offenders |url=https://predanie.ru/book/91934-blazhennye-pohaby/ |website=predanie.ru |publisher=Orthodox Portal "Predanie" |access-date=23 October 2020 |language=ru|quote=he is privileged to ridicule, burlesque and defile the most sacred and important ceremonies… licensed to behave as no ordinary mortals would dream of behaving}}</ref>{{efn|This Holy Fool's character development also explicitly references the controversial "bears appearance" scene in Bible. When a group of boys (or youths<ref>Hebrew ''na'ar'', translated "youths" in the [[New International Version]]. ''[[Jewish Encyclopedia]]'' on [http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/5682-elisha Elisha] states, "The offenders were not children, but were called so ("ne'arim") because they lacked ("meno'arin") all religion ([[Soṭah]] 46b)." Although the [[Authorized King James Version]] used the words "little children", theologian [[John Gill (theologian)|John Gill]] stated in his [http://www.biblestudytools.com/commentaries/gills-exposition-of-the-bible/2-kings-2-23.html ''Exposition of the Bible''] that the word was "used of persons of thirty or forty years of age".</ref>) from Bethel taunted the prophet [[Elisha]] for his baldness, Elisha cursed them in the name of [[Yahweh]] and two female bears came out of the forest and tore forty-two of the boys.<ref name=duffy>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Duffy |first=Daniel |year=1909 |title=Eliseus |url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05386c.htm |encyclopedia=[[The Catholic Encyclopedia]] |volume=5 |location=New York |publisher=Robert Appleton Company |access-date=7 January 2014}}</ref> Holy Fool finishes the opera, 2nd edition, as a prophet. [[Tchaikovsky]] used to call Mussorgsky "a bear" as an insult.<ref>{{cite web |title=Tchaikovsky: Between Heaven and Hell |url=https://www.youtube.com/embed/nXb4XT3lwQQ?start=1199 |website=[[YouTube]] |publisher=[[TV Center]] |access-date=29 September 2020 |language=ru|date=4 January 2020}}</ref>}} In other roles lists created by Mussorgsky, Pimen is designated a monk (инок), Grigoriy a novice (послушник), Rangoni a Cardinal (кардинал), Varlaam and Misail vagrant-monks (бродяги-чернецы), the Innkeeper a hostess (хозяйка), and Khrushchov a Voyevoda (воевода).<ref>Orlova, Pekelis (1971: pp. 198–199)</ref> Pimen, Grigoriy, Varlaam, and Misail were likely given non-clerical designations to satisfy the censor. |

* {{cite web |title=Блаженные похабы |trans-title=The Blessed Offenders |url=https://predanie.ru/book/91934-blazhennye-pohaby/ |website=predanie.ru |publisher=Orthodox Portal "Predanie" |access-date=23 October 2020 |language=ru|quote=he is privileged to ridicule, burlesque and defile the most sacred and important ceremonies… licensed to behave as no ordinary mortals would dream of behaving}}</ref>{{efn|This Holy Fool's character development also explicitly (see also the [[Novgorod]] [[:File:Tsarskiy titulyarnik emblems.jpg|coat of arms]] and [[Mussorgsky family]] history) references the controversial "bears appearance" scene in Bible. When a group of boys (or youths<ref>Hebrew ''na'ar'', translated "youths" in the [[New International Version]]. ''[[Jewish Encyclopedia]]'' on [http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/5682-elisha Elisha] states, "The offenders were not children, but were called so ("ne'arim") because they lacked ("meno'arin") all religion ([[Soṭah]] 46b)." Although the [[Authorized King James Version]] used the words "little children", theologian [[John Gill (theologian)|John Gill]] stated in his [http://www.biblestudytools.com/commentaries/gills-exposition-of-the-bible/2-kings-2-23.html ''Exposition of the Bible''] that the word was "used of persons of thirty or forty years of age".</ref>) from Bethel taunted the prophet [[Elisha]] for his baldness, Elisha cursed them in the name of [[Yahweh]] and two female bears came out of the forest and tore forty-two of the boys.<ref name=duffy>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Duffy |first=Daniel |year=1909 |title=Eliseus |url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05386c.htm |encyclopedia=[[The Catholic Encyclopedia]] |volume=5 |location=New York |publisher=Robert Appleton Company |access-date=7 January 2014}}</ref> Holy Fool finishes the opera, 2nd edition, as a prophet. [[Tchaikovsky]] used to call Mussorgsky "a bear" as an insult.<ref>{{cite web |title=Tchaikovsky: Between Heaven and Hell |url=https://www.youtube.com/embed/nXb4XT3lwQQ?start=1199 |website=[[YouTube]] |publisher=[[TV Center]] |access-date=29 September 2020 |language=ru|date=4 January 2020}}</ref>}} In other roles lists created by Mussorgsky, Pimen is designated a monk (инок), Grigoriy a novice (послушник), Rangoni a Cardinal (кардинал), Varlaam and Misail vagrant-monks (бродяги-чернецы), the Innkeeper a hostess (хозяйка), and Khrushchov a Voyevoda (воевода).<ref>Orlova, Pekelis (1971: pp. 198–199)</ref> Pimen, Grigoriy, Varlaam, and Misail were likely given non-clerical designations to satisfy the censor. |

||

==Instrumentation== |

==Instrumentation== |

||

Revision as of 00:36, 6 January 2021

| Boris Godunov | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Modest Mussorgsky | |

The death of Boris in the Faceted Palace from the premiere production | |

| Native title | |

| Librettist | Mussorgsky |

| Language | Russian |

| Based on | Boris Godunov by Alexander Pushkin and History of the Russian State by Nikolay Karamzin |

| Premiere | 27 January 1874 Mariinsky Theatre, Saint Petersburg |

Boris Godunov (Template:Lang-ru, Borís Godunóv) is an opera by Modest Mussorgsky (1839–1881). The work was composed between 1868 and 1873 in Saint Petersburg, Russia. It is Mussorgsky's only completed opera and is considered his masterpiece.[1][2] Its subjects are the Russian ruler Boris Godunov, who reigned as Tsar (1598 to 1605) during the Time of Troubles, and his nemesis, the False Dmitriy (reigned 1605 to 1606). The Russian-language libretto was written by the composer, and is based on the 1825 drama Boris Godunov by Aleksandr Pushkin, and, in the Revised Version of 1872, on Nikolay Karamzin's History of the Russian State.

Among major operas, Boris Godunov shares with Giuseppe Verdi's Don Carlos (1867) the distinction of having an extremely complex creative history, as well as a great wealth of alternative material.[3] The composer created two versions—the Original Version of 1869, which was rejected for production by the Imperial Theatres, and the Revised Version of 1872, which received its first performance in 1874 in Saint Petersburg.

Boris Godunov has seldom been performed in either of the two forms left by the composer,[4] frequently being subjected to cuts, recomposition, re-orchestration, transposition of scenes, or conflation of the original and revised versions.

Several composers, chief among them Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov and Dmitri Shostakovich, have created new editions of the opera to "correct" perceived technical weaknesses in the composer's original scores. Although these versions held the stage for decades, Mussorgsky's individual harmonic style and orchestration are now valued for their originality, and revisions by other hands have fallen out of fashion.

In the 1980s, Boris Godunov was closer to the status of a repertory piece than any other Russian opera, even Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin,[5] and is the most recorded Russian opera.[6]

History

Composition history

Note: Dates provided in this article for events taking place in Russia before 1918 are Old Style.

-

Nikolay Karamzin

(1766–1826) -

Alexander Pushkin

(1799–1837) -

Vladimir Stasov

(1824–1906) -

Vladimir Nikolsky

(1836–1883)

By the close of 1868, Mussorgsky had already started and abandoned two important opera projects—the antique, exotic, romantic tragedy Salammbô, written under the influence of Aleksandr Serov's Judith, and the contemporary, Russian, anti-romantic farce Marriage, influenced by Aleksandr Dargomïzhsky's The Stone Guest. Mussorgsky's next project would be a very original and successful synthesis of the opposing styles of these two experiments—the romantic-lyrical style of Salammbô, and the realistic style of Marriage.[7]

In the autumn of 1868, Vladimir Nikolsky, a professor of Russian history and language, and an authority on Pushkin, suggested to Mussorgsky the idea of composing an opera on the subject of Pushkin's "dramatic chronicle" Boris Godunov.[8] Boris the play, modelled on Shakespeare's histories,[9] was written in 1825 and published in 1831, but was not approved for performance by the state censors until 1866, almost 30 years after the author's death. Production was permitted on condition that certain scenes were cut.[10][11] Although enthusiasm for the work was high, Mussorgsky faced a seemingly insurmountable obstacle to his plans in that an Imperial ukaz of 1837 forbade the portrayal in opera of Russian Tsars (amended in 1872 to include only Romanov Tsars).[12]

Original Version

When Lyudmila Shestakova, the sister of Mikhail Glinka, learned of Mussorgsky's plans, she presented him with a volume of Pushkin's dramatic works, interleaved with blank pages and bound, and using this, Mussorgsky began work in October 1868 preparing his own libretto.[13] Pushkin's drama consists of 25 scenes, written predominantly in blank verse. Mussorgsky adapted the most theatrically effective scenes, mainly those featuring the title character, along with a few other key scenes (Novodevichy, Cell, Inn), often preserving Pushkin's verses.[14]

Mussorgsky worked rapidly, composing first the vocal score in about nine months (finished 18 July 1869), and completed the full score five months later (15 December 1869), at the same time working as a civil servant.[13][15] In 1870, he submitted the libretto to the state censor for examination, and the score to the literary and music committees of the Imperial Theatres.[16] However, the opera was rejected (10 February 1871) by a vote of 6 to 1, ostensibly for its lack of an important female role.[17] Lyudmila Shestakova recalled the reply made by conductor Eduard Nápravník and stage manager Gennadiy Kondratyev of the Mariinsky Theatre in response to her question of whether Boris had been accepted for production:[18]

"'No,' they answered me, 'it's impossible. How can there be an opera without the feminine element?! Mussorgsky has great talent beyond doubt. Let him add one more scene. Then Boris will be produced!'"[18]

— Lyudmila Shestakova, in My Evenings, her recollections of Mussorgsky and The Mighty Handful, 1889

Other questionable accounts, such as Rimsky-Korsakov's, allege that there were additional reasons for rejection, such as the work's novelty:[18]

"...Mussorgsky submitted his completed Boris Godunov to the Board of Directors of the Imperial Theatres ... The freshness and originality of the music nonplussed the honorable members of the committee, who reproved the composer, among other things, for the absence of a reasonably important female role."[19]

— Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, Chronicle of My Musical Life, 1909

"All his closest friends, including myself, although moved to enthusiasm by the superb dramatic power and genuinely national character of the work, had constantly been pointing out to him that it lacked many essentials; and that despite the beauties with which it teemed, it might be found unsatisfactory in certain respects. For a long time he stood up (as every genuine artist is wont to do) for his creation, the fruit of his inspiration and meditations. He yielded only after Boris had been rejected, the management finding that it contained too many choruses and ensembles, whereas individual characters had too little to do. This rejection proved very beneficial to Boris."[20]

— Vladimir Stasov

Meanwhile, Pushkin's drama (18 of the published 24 scenes, condensed into 16) finally received its first performance in 1870 at the Mariinsky Theatre, three years in advance of the premiere of the opera in the same venue, using the same scene designs by Matvey Shishkov that would be recycled in the opera.[10][11]

Revised Version

In 1871, Mussorgsky began recasting and expanding the opera with enthusiasm, ultimately going beyond the requirements of the directorate of the Imperial Theatres, which called simply for the addition of a female role and a scene to contain it.[17] He added three scenes (the two Sandomierz scenes and the Kromï Scene), cut one (The Cathedral of Vasiliy the Blessed), and recomposed another (the Terem Scene). The modifications resulted in the addition of an important prima donna role (Marina Mniszech), the expansion of existing female roles (additional songs for the Hostess, Fyodor, and the Nurse), and the expansion of the first tenor role (the Pretender). Mussorgsky augmented his adaptation of Pushkin's drama with his own lyrics, assisted by a study of the monumental History of the Russian State by Karamzin, to whom Pushkin's drama is dedicated. The Revised Version was finished in 1872 (vocal score, 14 December 1871; full score 23 June 1872),[15] and submitted to the Imperial Theatres in the autumn.

Most Mussorgsky biographers claim that the directorate of the Imperial Theatres also rejected the revised version of Boris Godunov, even providing a date: 6 May 1872 (Calvocoressi),[23] or 29 October 1872 (Lloyd-Jones).[24] Recent researchers point out that there is insufficient evidence to support this claim, emphasizing that in his revision Mussorgsky had rectified the only objection the directorate is known to have made.[25]

In any case, Mussorgsky's friends took matters into their own hands, arranging the performance of three scenes (the Inn and both Sandomierz scenes) at the Mariinsky Theatre on 5 February 1873, as a benefit for stage manager Gennadiy Kondratyev.[15] César Cui's review noted the audience's enthusiasm:

"The success was enormous and complete; never, within my memory, had such ovations been given to a composer at the Mariinsky."[26]

— César Cui, Sankt-Peterburgskie Vedomosti, 1873

The success of this performance led V. Bessel and Co. to announce the publication of the piano vocal score of Mussorgsky's opera, issued in January 1874.[15]

Premiere

The triumphant 1873 performance of three scenes paved the way for the first performance of the opera, which was accepted for production on 22 October 1873.[27] The premiere took place on 27 January 1874, as a benefit for prima donna Yuliya Platonova.[15] The performance was a great success with the public. The Mariinsky Theatre was sold out; Mussorgsky had to take some 20 curtain calls; students sang choruses from the opera in the street. This time, however, the critical reaction was exceedingly hostile[28] [see Critical Reception in this article for details].

Initial performances of Boris Godunov featured significant cuts. The entire Cell Scene was cut from the first performance, not, as is often supposed, due to censorship, but because Nápravník wished to avoid a lengthy performance, and frequently cut episodes he felt were ineffective.[29] Later performances tended to be even more heavily cut, including the additional removal of the Kromï scene, likely for political reasons (starting 20 October 1876, the 13th performance).[30] After protracted difficulties in obtaining the production of his opera, Mussorgsky was compliant with Nápravník's demands, and even defended these mutilations to his own supporters.

"Presently cuts were made in the opera, the splendid scene 'Near Kromï' was omitted. Some two years later, the Lord knows why, productions of the opera ceased altogether, although it had enjoyed uninterrupted success, and the performances under Petrov and, after his death, by F. I. Stravinsky, Platonova, and Komissarzhevsky had been excellent. There were rumors afloat that the opera had displeased the Imperial family; there was gossip that its subject was unpleasant to the censors; the result was that the opera was stricken from the repertory."[31]

— Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, Chronicle of My Musical Life

Boris Godunov was performed 21 times during the composer's lifetime, and 5 times after his death (in 1881) before being withdrawn from the repertory on 8 November 1882. When Mussorgsky's subsequent opera Khovanshchina was rejected for production in 1883, the Imperial Opera Committee reputedly said: "One radical opera by Mussorgsky is enough."[32] Boris Godunov did not return to the stage of the Mariinsky Theatre until 9 November 1904, when the Rimsky-Korsakov edition was presented under conductor Feliks Blumenfeld with bass Feodor Chaliapin in the title role.

Boris Godunov and the Imperial Family

The reports of the antipathy of the Imperial family to Mussorgsky's opera are supported by the following accounts by Platonova and Stasov:

"During the [premiere], after the scene by the fountain, Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich, a devoted friend of mine, but by the calumny of the Conservatory members, the sworn enemy of Musorgsky, approached me during the intermission with the following words: 'And you like this music so much that you chose this opera for a benefit performance?' 'I like it, Your Highness,' I answered. 'Then I am going to tell you that this is a shame to all Russia, and not an opera!' he screamed, almost foaming at the mouth, and then turning his back, he stomped away from me."[33]

— Yuliya Platonova, letter to Vladimir Stasov

"In the entire audience, I think only Konstantin Nikolayevich was unhappy (he does not like our school, in general) ... it was not so much the fault of the music as that of the libretto, where the 'folk scenes,' the riot, the scene where the police officer beats the people with his stick so that they cry out begging Boris to accept the throne, and so forth, were jarring to some people and infuriated them. There was no end to applause and curtain calls."[34]

— Vladimir Stasov, letter to his daughter, 1874

"When the list of operas for the winter was presented to His Majesty the Emperor, he, with his own hand, was pleased to strike out Boris with a wavy line in blue pencil."[35]

— Vladimir Stasov, letter to Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, 1888

Performance history

Note: This section lists performance data for the Saint Petersburg and Moscow premieres of each important version, the first performance of each version abroad, and premieres in English-speaking countries. Dates provided for events taking place in Russia before 1918 are Old Style.

Original interpreters

1872, Saint Petersburg – Excerpts

The Coronation Scene was performed on 5 February 1872 by the Russian Music Society, conducted by Eduard Nápravník. The Polonaise from Act 3 was performed (without chorus) on 3 April 1872 by the Free School of Music, conducted by Miliy Balakirev.[36]

1873, Saint Petersburg – Three scenes

Three scenes from the opera—the Inn Scene, the Scene in Marina's Boudoir, and the Fountain Scene—were performed on 5 February 1873 at the Mariinsky Theatre. Eduard Nápravník conducted.[26] The cast included Darya Leonova (Innkeeper), Fyodor Komissarzhevsky (Pretender), Osip Petrov (Varlaam), Vasiliy Vasilyev (or 'Vasilyev II') (Misail), Mikhail Sariotti (Police Officer), Yuliya Platonova (Marina), Josef Paleček (Rangoni), and Feliks Krzesiński (Old Polish Noble).[37]

1874, Saint Petersburg – World premiere

The Revised Version of 1872 received its world premiere on 27 January 1874 at the Mariinsky Theatre. The Cell Scene was omitted. The Novodevichiy and Coronation scenes were combined into one continuous scene: 'The Call of Boris to the Tsardom'. Matvey Shishkov's design for the last scene of Pushkin's drama, 'The House of Boris' (see illustration, right), was substituted for this hybrid of the Novodevichiy and Coronation scenes.[38] The scenes were grouped in five acts as follows:[39]

- Act 1: 'The Call of Boris to the Tsardom' and 'Inn'

- Act 2: 'With Tsar Boris'

- Act 3: 'Marina's Boudoir' and 'At the Fountain'

- Act 4: 'The Death of Boris'

- Act 5: 'The Pretender near Kromï'

Production personnel included Gennadiy Kondratyev (stage director), Ivan Pomazansky (chorus master), Matvey Shishkov, Mikhail Bocharov, and Ivan Andreyev (scene designers), and Vasiliy Prokhorov (costume designer). Eduard Nápravník conducted. The cast included Ivan Melnikov (Boris), Aleksandra Krutikova (Fyodor), Wilhelmina Raab (Kseniya), Olga Shryoder (nurse), Vasiliy Vasilyev, 'Vasilyev II' (Shuysky), Vladimir Sobolev (Shchelkalov), Vladimir Vasilyev, 'Vasilyev I' (Pimen, Lawicki), Fyodor Komissarzhevsky (Pretender), Yuliya Platonova (Marina), Josef Paleček (Rangoni), Osip Petrov (Varlaam), Pavel Dyuzhikov (Misail), Antonina Abarinova (Innkeeper), Pavel Bulakhov (Yuródivïy), Mikhail Sariotti (Nikitich), Lyadov (Mityukha), Sobolev (Boyar-in-Attendance), Matveyev (Khrushchov), and Sobolev (Czernikowski). The production ran for 26 performances over 9 years.[40]

The premiere established traditions that have influenced subsequent Russian productions (and many abroad as well): 1) Cuts made to shorten what is perceived as an overlong work; 2) Declamatory and histrionic singing by the title character, often degenerating in climactic moments into shouting (initiated by Ivan Melnikov, and later reinforced by Fyodor Shalyapin); and 3) Realistic and historically accurate sets and costumes, employing very little stylization.[41]

1879, Saint Petersburg – Cell Scene

The Cell Scene (Revised Version) was first performed on 16 January 1879 in Kononov Hall, at a concert of the Free School of Music, in the presence of Mussorgsky.[42] Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov conducted. The cast included Vladimir Vasilyev, "Vasilyev I" (Pimen), and Vasiliy Vasilyev, 'Vasilyev II' (Pretender).[43][44]

1888, Moscow – Bolshoy Theatre premiere

The Revised Version of 1872 received its Moscow premiere on 16 December 1888 at the Bolshoy Theatre. The Cell and Kromï scenes were omitted. Production personnel included Anton Bartsal (stage director), and Karl Valts (scene designer). Ippolit Altani conducted. The cast included Bogomir Korsov (Boris), Nadezhda Salina (Fyodor), Aleksandra Karatayeva (Kseniya), O. Pavlova (Nurse), Anton Bartsal (Shuysky), Pyotr Figurov (Shchelkalov), Ivan Butenko (Pimen), Lavrentiy Donskoy (Pretender), Mariya Klimentova (Marina), Pavel Borisov (Rangoni), Vladimir Streletsky (Varlaam), Mikhail Mikhaylov (Misail), Vera Gnucheva (Innkeeper), and Aleksandr Dodonov (Boyar-in-attendance). The production ran for 10 performances.[40][45]

1896, Saint Petersburg – Premiere of the Rimsky-Korsakov edition

The Rimsky-Korsakov edition premiered on 28 November 1896 in the Great Hall of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov conducted. The cast included Mikhail Lunacharsky (Boris), Gavriil Morskoy (Pretender), Nikolay Kedrov (Rangoni), and Fyodor Stravinsky (Varlaam). The production ran for 4 performances.[40]

1898, Moscow – Fyodor Shalyapin as Boris

Bass Fyodor Shalyapin first appeared as Boris on 7 December 1898 at the Solodovnikov Theatre in a Private Russian Opera production. The Rimsky-Korsakov edition of 1896 was performed. Production personnel included Savva Mamontov (producer), and Mikhail Lentovsky (stage director). Giuseppe Truffi conducted. The cast also included Anton Sekar-Rozhansky (Pretender), Serafima Selyuk-Roznatovskaya (Marina), Varvara Strakhova (Fyodor), and Vasiliy Shkafer (Shuysky). The production ran for 14 performances.[40]

1908, Paris – First performance outside Russia

The Rimsky-Korsakov edition of 1908 premiered on 19 May 1908 at the Paris Opéra. The Cell Scene preceded the Coronation Scene, the Inn Scene and the Scene in Marina's Boudoir were omitted, the Fountain Scene preceded the Terem Scene, and the Kromï Scene preceded the Death Scene. Production personnel included Sergey Dyagilev (producer), Aleksandr Sanin (stage director), Aleksandr Golovin, Konstantin Yuon, Aleksandr Benua, and Yevgeniy Lansere (scene designers), Ulrikh Avranek (chorusmaster), and Ivan Bilibin (costume designer). Feliks Blumenfeld conducted. The cast included Fyodor Shalyapin (Boris), Klavdiya Tugarinova (Fyodor), Dagmara Renina (Kseniya), Yelizaveta Petrenko (Nurse), Ivan Alchevsky (Shuysky), Nikolay Kedrov (Shchelkalov), Vladimir Kastorsky (Pimen), Dmitri Smirnov (Pretender), Nataliya Yermolenko-Yuzhina (Marina), Vasiliy Sharonov (Varlaam), Vasiliy Doverin-Kravchenko (Misail), Mitrofan Chuprïnnikov (Yuródivïy), and Khristofor Tolkachev (Nikitich).[40] The production ran for 7 performances.[46]

1913, New York – United States premiere

The United States premiere of the 1908 Rimsky-Korsakov edition took place on 19 March 1913 at the Metropolitan Opera, and was based on Sergey Dyagilev's Paris production. The opera was presented in three acts. The Cell Scene preceded the Coronation Scene, the scene in Marina's Boudoir was omitted, and the Kromï Scene preceded the Death Scene. However, the Inn Scene, which was omitted in Paris, was included. Scenery and costume designs were the same as used in Paris in 1908—made in Russia by Golovin, Benua, and Bilibin, and shipped from Paris. The opera was sung in Italian. Arturo Toscanini conducted. The cast included Adamo Didur (Boris), Anna Case (Fyodor), Leonora Sparkes (Kseniya), Maria Duchêne (Nurse), Angelo Badà (Shuysky), Vincenzo Reschiglian (Shchelkalov, Lawicki), Jeanne Maubourg (Innkeeper), Léon Rothier (Pimen), Paul Althouse (Pretender), Louise Homer (Marina), Andrés de Segurola (Varlaam), Pietro Audisio (Misail), Albert Reiss (Yuródivïy), Giulio Rossi (Nikitich), Leopoldo Mariani (Boyar-in-Attendance), and Louis Kreidler (Czernikowski).[47]

1913, London – United Kingdom premiere

The United Kingdom premiere of the 1908 Rimsky-Korsakov edition took place on 24 June 1913 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London. Production personnel included Sergey Dyagilev (producer) and Aleksandr Sanin (stage director). Emil Cooper conducted. The cast included Fyodor Shalyapin (Boris), Mariya Davïdova (Fyodor), Mariya Brian (Kseniya), Yelizaveta Petrenko (Nurse, Innkeeper), Nikolay Andreyev (Shuysky), A. Dogonadze (Shchelkalov), Pavel Andreyev (Pimen), Vasiliy Damayev (Pretender), Yelena Nikolayeva (Marina), Aleksandr Belyanin (Varlaam), Nikolay Bolshakov (Misail), Aleksandr Aleksandrovich (Yuródivïy), and Kapiton Zaporozhets (Nikitich).[40]

1927, Moscow – St. Basil's Scene

The newly published St. Basil's Scene was performed on 18 January 1927 at the Bolshoy Theatre in the 1926 revision by Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov, commissioned in 1925 to accompany the Rimsky-Korsakov edition. Production personnel included Vladimir Lossky (stage director) and Fyodor Fedorovsky (scene designer). Ariy Pazovsky conducted. The cast included Ivan Kozlovsky (Yuródivïy), and Leonid Savransky (Boris).[48] The production ran for 144 performances.[40]

1928, Leningrad – World premiere of the 1869 Original Version

The Original Version of 1869 premiered on 16 February 1928 at the State Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet. Production personnel included Sergey Radlov (stage director), and Vladimir Dmitriyev (scene designer). Vladimir Dranishnikov conducted. The cast included Mark Reyzen (Boris), Aleksandr Kabanov (Shuysky), Ivan Pleshakov (Pimen), Nikolay Pechkovsky (Pretender), Pavel Zhuravlenko (Varlaam), Yekaterina Sabinina (Innkeeper), and V. Tikhiy (Yuródivïy).[40]

1935, London – First performance of the 1869 Original Version outside Russia

The first performance of the 1869 Original Version abroad took place on 30 September 1935 at the Sadler's Wells Theatre. The opera was sung in English. Lawrance Collingwood conducted. The cast included Ronald Stear (Boris).[49]

1959, Leningrad – First performance of the Shostakovich orchestration

The premiere of the Shostakovich orchestration of 1940 of Pavel Lamm's vocal score took place on 4 November 1959 at the Kirov Theatre. Sergey Yeltsin conducted. The cast included Boris Shtokolov (Boris).

1974, New York – First Russian Language Performance

On 16 December 1974, am adapted version of the original Mussorgsky orchestration was used for this New production, with Martti Talvela performing the title role by the Metropolitan Opera.

Publication history

| Year | Score | Editor | Publisher | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1874 | Piano vocal score | Modest Mussorgsky | V. Bessel and Co., Saint Petersburg | Revised Version |

| 1896 | Full score | Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov | V. Bessel and Co., Saint Petersburg | A drastically edited, re-orchestrated, and cut form of the 1874 vocal score |

| 1908 | Full score | Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov | V. Bessel and Co., Saint Petersburg | A drastically edited and re-orchestrated form of the 1874 vocal score |

| 1928 | Piano vocal score | Pavel Lamm | Muzsektor, Moscow; Oxford University Press, London | A restoration of the composer's scores; a conflation of the Original and Revised Versions, but with notes identifying the sources |

| Full score | Pavel Lamm and Boris Asafyev | Muzsektor, Moscow; Oxford University Press, London | A restoration of the composer's scores; a conflation of the Original and Revised Versions; limited edition of 200 copies | |

| 1963 | Full score | Dmitriy Shostakovich | Muzgiz, Moscow | A new orchestration of Lamm's vocal score; a conflation of the Original and Revised Versions |

| 1975 | Full score | David Lloyd-Jones | Oxford University Press, London | A restoration of the composer's scores; a conflation of the Original and Revised Versions, but with notes identifying the sources |

Versions

Note: Musicologists are often not in agreement on the terms used to refer to the two authorial versions of Boris Godunov. Editors Pavel Lamm and Boris Asafyev used "preliminary redaction" and "principal redaction" for the 1st and 2nd versions, respectively,[50] and David Lloyd-Jones designated them "initial" and "definitive."[51] This article, aiming for utmost objectivity, uses "original" and "revised."

The differences in approach between the two authorial versions are sufficient as to constitute two distinct ideological conceptions, not two variations of a single plan.[52][53]

1869 Original Version

The Original Version of 1869 is rarely heard. It is distinguished by its greater fidelity to Pushkin's drama and its almost entirely male cast of soloists. It also conforms to the recitative opera style (opéra dialogué) of The Stone Guest and Marriage, and to the ideals of kuchkist realism, which include fidelity to text, formlessness, and emphasis on the values of spoken theatre, especially through naturalistic declamation.[53][54] The unique features of this version include:

- Pimen's narrative of the scene of the murder of Dmitriy Ivanovich (Part 2, Scene 1)

- The original Terem Scene (Part 3), which follows Pushkin's text more closely than does the revised version.

- The scene 'The Cathedral of Vasiliy the Blessed' (the 'St. Basil's Scene'—Part 4, Scene 1)

The terse Terem Scene of the 1869 version and the unrelieved tension of the two subsequent and final scenes make this version more dramatically effective to some critics (e.g., Boris Asafyev).[55]

1872 Revised Version

The Revised Version of 1872 represents a retreat from the ideals of Kuchkist realism, which had come to be associated with comedy, toward a more exalted, tragic tone, and a conventionally operatic style—a trend that would be continued in the composer's next opera, Khovanshchina.[56] This version is longer, is richer in musical and theatrical variety,[57] and balances naturalistic declamation with more lyrical vocal lines. The unique features of this version include:

- Two new offstage choruses of monks in the otherwise abbreviated Cell Scene (Act 1, Scene 1)

- The innkeeper's 'Song of the Drake' (Act 1, Scene 2)

- The revised Terem Scene (Act 2), which presents the title character in a more tragic and melodramatic light, and includes new songs and new musical themes borrowed from Salammbô[58]

- The conventionally operatic 'Polish' act (Act 3)

- The novel final scene of anarchy (the Kromï Scene—Act 4, Scene 2)

Mussorgsky rewrote the Terem Scene for the 1872 version, modifying the text, adding new songs and plot devices (the parrot and the clock), modifying the psychology of the title character, and virtually recomposing the music of the entire scene.

This version has made a strong comeback in recent years, and has become the dominant version.

1874 Piano Vocal Score

The Piano Vocal Score of 1874 was the first published form of the opera, and is essentially the 1872 version with some minor musical variants and small cuts. The 1874 vocal score does not constitute a 'third version', but rather a refinement of the 1872 Revised Version.[15]

Scene structure

The distribution of scenes in the authorial versions is as follows:

| Scene | Short name | Original Version 1869 | Revised Version 1872 |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Courtyard of the Novodevichiy Monastery | Novodevichy Scene | Part 1, Scene 1 | Prologue, Scene 1 |

| A Square in the Moscow Kremlin | Coronation Scene | Part 1, Scene 2 | Prologue, Scene 2 |

| A Cell in the Chudov Monastery | Cell Scene | Part 2, Scene 1 | Act 1, Scene 1 |

| An Inn on the Lithuanian Border | Inn Scene | Part 2, Scene 2 | Act 1, Scene 2 |

| The Tsar's Terem in the Moscow Kremlin | Kremlin Scene | Part 3 | Act 2 |

| Marina's Boudoir in Sandomierz | Act 3, Scene 1 | ||

| The Garden of Mniszech's Castle in Sandomierz | Fountain Scene | Act 3, Scene 2 | |

| The Cathedral of Vasiliy the Blessed | St. Basil's Scene | Part 4, Scene 1 | |

| The Faceted Palace in the Moscow Kremlin | Death Scene | Part 4, Scene 2 | Act 4, Scene 1 |

| A Forest Glade near Kromï | Revolution Scene | Act 4, Scene 2 |

Upon revising the opera, Mussorgsky initially replaced the St. Basil's Scene with the Kromï Scene. However, on the suggestion of Vladimir Nikolsky, he transposed the order of the last two scenes, concluding the opera with the Kromï Scene rather than the Faceted Palace Scene. This gives the overall structure of the 1872 Revised Version the following symmetrical form:[59]

| Act | Scene | Character Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Prologue | Novodevichy | People |

| Cathedral Square | Boris | |

| Act 1 | Cell | Pretender |

| Inn | ||

| Act 2 | Terem | Boris |

| Act 3 | Marina's Boudoir | Pretender |

| Fountain | ||

| Act 4 | Faceted Palace | Boris |

| Near Kromï | People |

Editions by other hands

- Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, 1896

- Rimsky-Korsakov, 1908

- Emilis Melngailis, 1924

- Dmitri Shostakovich, 1940

- Karol Rathaus, 1952

The Rimsky-Korsakov Version of 1908 has been the most traditional version over the last century, but has recently been almost entirely eclipsed by Mussorgsky's Revised Version (1872). It resembles the Vocal Score of 1874, but the order of the last two scenes is reversed [see Versions by Other Hands in this article for more details].

Roles

Note: Roles designated with an asterisk (*) do not appear in the 1869 Original Version. 'Yuródivïy' is often translated as 'Simpleton' or 'Idiot'. However, 'Holy Fool' is a more accurate English equivalent.[61][a] In other roles lists created by Mussorgsky, Pimen is designated a monk (инок), Grigoriy a novice (послушник), Rangoni a Cardinal (кардинал), Varlaam and Misail vagrant-monks (бродяги-чернецы), the Innkeeper a hostess (хозяйка), and Khrushchov a Voyevoda (воевода).[65] Pimen, Grigoriy, Varlaam, and Misail were likely given non-clerical designations to satisfy the censor.

Instrumentation

Mussorgsky orchestration

- Strings: violins I & II, violas, cellos, double basses

- Woodwinds: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling english horn), 3 clarinets, 2 bassoons

- Brass: 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, 1 tuba

- Percussion: timpani, bass drum, snare drum, tambourine, cymbals

- Other: piano, harp

- On/Offstage instruments: 1 trumpet, bells, tam-tam

Rimsky-Korsakov orchestration

- Strings: violins I & II, violas, cellos, double basses

- Woodwinds: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling english horn), 3 clarinets (3rd doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons

- Brass: 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, 1 tuba

- Percussion: timpani, bass drum, snare drum, tambourine, cymbals

- Other: piano, harp

- On/Offstage instruments: 1 trumpet, bells, tam-tam

Shostakovich orchestration

- Strings: violins I & II, violas, cellos, double basses

- Woodwinds: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, english horn, 3 clarinets (3rd doubling E-flat clarinet), bass clarinet, 3 bassoons (3rd doubling contrabassoon)

- Brass: 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, 1 tuba

- Percussion: timpani, bass drum, snare drum, cymbals, tam-tam, triangle, bells, glockenspiel, xylophone

- Other: piano, harp, celesta

- On/Offstage instruments: 4 trumpets, 2 cornets, 2 horns, 2 baritone horns, 2 euphoniums, 2 tubas, balalaika and domra ad libitum

Historical basis of the plot

-

Boris Godunov

(1551–1605) -

Vasiliy Shuysky

(1552–1612) -

The Pretender

(c. 1582–1606) -

Marina Mniszech

(1588–1614)

An understanding of the drama of Boris Godunov may be facilitated by a basic knowledge of the historical events surrounding the Time of Troubles, the interregnum of relative anarchy following the end of the Ryurik Dynasty (1598) and preceding the Romanov Dynasty (1613). Key events are as follows:

- 1584 – Ivan IV "The Terrible", the first Grand Prince of Muscovy to officially adopt the title Tsar (Caesar), dies. Ivan's successor is his feeble son, Fyodor I, who cares only for spiritual matters and leaves the affairs of state to his capable brother-in-law, boyar Boris Godunov.

- 1591 – Ivan's other son, the eight-year-old Tsarevich Dmitriy Ivanovich, dies under mysterious circumstances in Uglich. An investigation, ordered by Godunov and carried out by Prince Vasiliy Shuysky, determines that the Tsarevich, while playing with a knife, suffered an epileptic seizure, fell, and died from a self-inflicted wound to the throat. Dmitriy's mother, Maria Nagaya, banished with him to Uglich by Godunov, claims he was assassinated. Rumors linking Boris to the death are circulated by his enemies.

- 1598 – Tsar Fyodor I dies. He is the last of the Ryurik Dynasty, who have ruled Russia for seven centuries. Patriarch Job of Moscow nominates Boris to succeed as Tsar, despite the rumors that Boris ordered the murder of Dmitriy. Boris agrees to accept the throne only if elected by the Zemsky Sobor. This the assembly does unanimously, and Boris is crowned the same year.

- 1601 – The Russian famine of 1601–1603 undermines Boris Godunov's popularity and the stability of his administration.

- 1604 – A pretender to the throne appears in Poland, claiming to be Tsarevich Dmitriy, but believed to be in reality one Grigoriy Otrepyev. He gains the support of the Szlachta, magnates, and, upon conversion to Roman Catholicism, the Apostolic Nuncio Claudio Rangoni. Obtaining a force of soldiers, he marches on Moscow. The False Dmitriy's retinue includes the Jesuits Lawicki and Czernikowski, and the monks Varlaam and Misail of the Chudov Monastery. Crossing into Russia, Dmitriy's invasion force is joined by disaffected Cossacks. However, after a few victories, the campaign falters. Polish mercenaries mutiny and desert.

- 1605 – Boris dies of unknown causes. He is succeeded by his son, Fyodor II. The death of Boris gives new life to the campaign of the False Dmitriy. Boyars who have gone over to the Pretender murder Fyodor II and his mother. The False Dmitriy enters Moscow and is soon crowned. Prince Shuysky begins plotting against him.

- 1606 – The Russian boyars oppose Dmitriy's Polish and Catholic alliances. He is murdered shortly after wedding Marina Mniszech, and is succeeded by Vasiliy Shuysky, now Vasiliy IV.

- 1610 – Battle of Klushino and Polish seizure and occupation of Moscow. Vasiliy IV is deposed, and dies two years later in a Polish prison. Another pretender claiming to be Dmitriy Ivanovich, False Dmitriy II, is murdered.

- 1611 – Yet a third pretender, False Dmitriy III, appears. He is captured and executed in 1612.

- 1613 – The Time of Troubles comes to a close with the accession of Mikhail Romanov, son of Fyodor Romanov, who had been persecuted under Boris Godunov's reign.

Note: The culpability of Boris in the matter of Dmitriy's death can neither be proved nor disproved. Karamzin accepted his responsibility as fact, and Pushkin and Mussorgsky after him assumed his guilt to be true, at least for the purpose of creating a tragedy in the mold of Shakespeare. Modern historians, however, tend to acquit Boris.

Synopsis

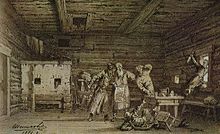

Note: Shishkov and Bocharev designed the sets (samples below), some of which were used in the first complete performance in 1874.

( ) = Arias and numbers

[ ] = Passages cut from or added to the 1872 Revised Version [see Versions in this article for details]

Setting

- Time: The years 1598 to 1605

- Place: Moscow; the Lithuanian frontier; a castle in Sandomierz; Kromï

Part 1 / Prologue

Scene 1: The Courtyard of the Novodevichiy Monastery near Moscow (1598)

There is a brief introduction foreshadowing the 'Dmitriy Motif'. The curtain opens on a crowd in the courtyard of the monastery, where the weary regent Boris Godunov has temporarily retired. Nikitich the police officer orders the assembled people to kneel. He goads them to clamor for Boris to accept the throne. They sing a chorus of supplication ("To whom dost thou abandon us, our father?"). The people are bewildered about their purpose and soon fall to bickering with each other, resuming their entreaties only when the policeman threatens them with his club. Their chorus reaches a feverish climax. Andrey Shchelkalov, the Secretary of the Duma, appears from inside the convent, informs the people that Boris still refuses the throne of Russia ("Orthodox folk! The boyar is implacable!"), and requests that they pray that he will relent. An approaching procession of pilgrims sings a hymn ("Glory to Thee, Creator on high"), exhorting the people to crush the spirit of anarchy in the land, take up holy icons, and go to meet the Tsar. They disappear into the monastery.

- [Original 1869 Version only: The people discuss the statements of the pilgrims. Many remain bewildered about the identity of this Tsar. The police officer interrupts their discussion, ordering them to appear the next day at the Moscow Kremlin. The people move on, stoically exclaiming "if we are to wail, we might as well wail at the Kremlin".]

Scene 2: [Cathedral] Square in the Moscow Kremlin (1598).

The orchestral introduction is based on bell motifs. From the porch of the Cathedral of the Dormition, Prince Shuysky exhorts the people to glorify Tsar Boris. As the people sing a great chorus of praise ("Like the beautiful sun in the sky, glory"), a solemn procession of boyars exits the cathedral. The people kneel. Boris appears on the porch of the cathedral. The shouts of "Glory!" reach a climax and subside. Boris delivers a brief monologue ("My soul grieves") betraying a feeling of ominous foreboding. He prays for God's blessing, and hopes to be a good and just ruler. He invites the people to a great feast, and then proceeds to the Cathedral of the Archangel to kneel at the tombs of Russia's past rulers. The people wish Boris a long life ("Glory! Glory! Glory!"). A crowd breaks toward the cathedral. The police officers struggle to maintain order. The people resume their shouts of "Glory!"

In this scene, Mussorgsky is hailed to be ahead of his time musically. His use of the whole tone scale, which uses only whole steps, made the Coronation scene stand out. This technique was replicated by impressionistic composers about 20 years later who noted his success. Mussorgsky also combined different two-beat and three-beat meters to create a unique sound for his composition called polymeters. These techniques were uncommon during this era and were believed to be almost too overwhelming for the public. This led to his rejection on two different occasions by the Imperial Opera before they decided to perform.[66]

Part 2 / Act 1

Scene 1: Night. A Cell in the Chudov Monastery [within the Moscow Kremlin] (1603)

Pimen, a venerable monk, writes a chronicle ("Yet one last tale") of Russian history. The young novice Grigoriy awakes from a horrible (and prophetic) dream, which he relates to Pimen, in which he climbed a high tower, was mocked by the people of Moscow, and fell. Pimen advises him to fast and pray. Grigoriy regrets that he retired so soon from worldly affairs to become a monk. He envies Pimen's early life of adventure. Pimen speaks approvingly of Ivan the Terrible and his son Fyodor, who both exhibited great spiritual devotion, and draws a contrast with Boris, a regicide.

- [Original 1869 Version only: At Grigoriy's request, Pimen tells the vivid details of the scene of the murder of Dmitriy Ivanovich, which he witnessed in Uglich.]

Upon discovering the similarity in age between himself and the murdered Tsarevich, Grigoriy conceives the idea of posing as the Pretender. As Pimen departs for Matins, Grigoriy declares that Boris shall escape neither the judgment of the people, nor that of God.

Scene 2: An Inn on the Lithuanian Border (1603)

There is a brief orchestral introduction based on three prominent themes from this scene.

- [Revised 1872 Version only: The Hostess enters and sings the 'Song of the Drake' ("I have caught a gray drake"). It is interrupted towards the end by approaching voices].

The vagrants Varlaam and Misail, who are dressed as monks and are begging for alms, and their companion Grigoriy, who is in secular garb, arrive and enter. After exchanging greetings, Varlaam requests some wine. When the Hostess returns with a bottle, he drinks and launches into a ferocious song ("So it was in the city of Kazan") of Ivan the Terrible's siege of Kazan. The two monks quickly become tipsy, and soon begin to doze. Grigoriy quietly asks the Hostess for directions to the Lithuanian border. The Hostess mentions that the police are watching the ordinary roads, but they are wasting their time, because there is an alternative, less well-known way to get to the border. Policemen appear in search of a fugitive heretic monk (Grigoriy) who has run off from the Chudov Monastery declaring that he will become Tsar in Moscow. Noticing Varlaam's suspicious appearance and behavior, the lead policeman thinks he has found his man. He cannot read the ukaz (edict) he is carrying, however, so Grigoriy volunteers to read it. He does so, but, eyeing Varlaam carefully, he substitutes Varlaam's description for his own. The policemen quickly seize Varlaam, who protests his innocence and asks to read the ukaz. Varlaam is only barely literate, but he manages to haltingly read the description of the suspect, which of course matches Grigoriy. Grigoriy brandishes a dagger, and leaps out of the window. The men set off in pursuit.

Part 3 / Act 2

The Interior of the Tsar's Terem in the Moscow Kremlin (1605)

Kseniya (or Xenia), clutching a portrait of "Prince Ivan", her betrothed who has died, sings a brief mournful aria ("Where are you, my bridegroom?"). Fyodor studies a great map of the Tsardom of Russia.

- [Revised 1872 Version only: Fyodor tries to console Kseniya and shows her the magic of the clock, once it starts chiming].

Kseniya's nurse assures her that she will soon forget about "Prince Ivan".

- [1872: The nurse and Fyodor attempt to cheer Kseniya up with some songs ("A gnat was chopping wood" and "A little tale of this and that").]

Boris abruptly enters, briefly consoles Kseniya, and then sends her and her nurse to their own quarters. Fyodor shows Boris the map of Russia. After encouraging his son to resume his studies, Boris delivers a long and fine soliloquy ("I have attained supreme power").

- [1872: At the end of this arioso he reveals that he has been disturbed by a vision of a bloody child begging for mercy. A commotion breaks out in his children's quarters. Boris sends Fyodor to investigate.]

The boyar-in-attendance brings word of the arrival of Prince Shuysky, and reports a denunciation against him for his intrigues.

- [1872: Fyodor returns to relate a whimsical tale ("Our little parrot was sitting") involving a pet parrot. Boris takes comfort in his son's imagination and advises Fyodor, when he becomes Tsar, to beware of evil and cunning advisors such as Shuysky.]

Prince Shuysky now enters. Boris insults him, accusing him of conspiring with Pushkin, an ancestor of the poet. However, the prince brings grave tidings. A Pretender has appeared in Lithuania. Boris angrily demands to know his identity. Shuysky fears the Pretender might attract a following bearing the name of Tsarevich Dmitriy. Shaken by this revelation, Boris dismisses Fyodor. He orders Shuysky to seal the border with Lithuania, and, clearly on the edge of madness, asks Shuysky whether he has ever heard of dead children rising from their graves to question Tsars. Boris seeks assurance that the dead child the prince had seen in Uglich was really Dmitriy. He threatens Shuysky, if he dissembles, with a gruesome execution. The Prince describes the ghastly scene of Dmitriy's murder in a brief and beautiful aria ("In Uglich, in the cathedral"). But he gives hints that a miracle (incorruptibility) has occurred. Boris begins choking with guilt and remorse, and gives a sign for Shuysky to depart.

- [1872: The chiming clock again begins working.]

Boris hallucinates (Hallucination or 'Clock' Scene). The spectre of the dead Dmitriy reaches out to him. Addressing the apparition, he denies his responsibility for the crime: "Begone, begone child! I am not thy murderer... the will of the people!" He collapses, praying that God will have mercy on his guilty soul.

Act 3 (The 'Polish' Act) (1872 Version only)

Scene 1: The Boudoir of Marina Mniszech in Sandomierz [Poland] (1604)

Maidens sing a delicate, sentimental song ("On the blue Vistula") to entertain Marina as her chambermaid dresses her hair. Marina declares her preference for heroic songs of chivalry. She dismisses everyone. Alone, she sings of her boredom ("How tediously and sluggishly"), of Dmitriy, and of her thirst for adventure, power, and glory. The Jesuit Rangoni enters, bemoans the wretched state of the church, attempts to obtain Marina's promise that when she becomes Tsaritsa she will convert the heretics of Moscow (Russian Orthodox Church) to the true faith (Roman Catholicism), and encourages her to bewitch the Pretender. When Marina wonders why she should do this, Rangoni angrily insists that she stop short of nothing, including sacrificing her honor, to obey the dictates of the church. Marina expresses contempt of his hypocritical insinuations and demands he leave. As Rangoni ominously tells her she is in the thrall of infernal forces, Marina collapses in dread. Rangoni demands her obedience.

Scene 2: Mniszech's Castle in Sandomierz. A Garden. A Fountain. A Moonlit Night (1604)

Woodwind and harp accompany a pensive version of the 'Dmitriy Motif'. The Pretender dreams of an assignation with Marina in the garden of her father's castle. However, to his annoyance, Rangoni finds him. He brings news that Marina longs for him and wishes to speak with him. The Pretender resolves to throw himself at Marina's feet, begging her to be his wife and Tsaritsa. He entreats Rangoni to lead him to Marina. Rangoni, however, first begs the Pretender to consider him a father, allowing him to follow his every step and thought. Despite his mistrust of Rangoni, the Pretender agrees not to part from him if he will only let him see Marina. Rangoni convinces the Pretender to hide as the Polish nobles emerge from the castle dancing a polonaise (Polonaise). Marina flirts, dancing with an older man. The Poles sing of taking the Muscovite throne, defeating the army of Boris, and capturing him. They return to the castle. The Pretender comes out of hiding, cursing Rangoni. He resolves to abandon wooing Marina and begin his march on Moscow. But then Marina appears and calls to him. He is lovesick. She, however, only wants to know when he will be Tsar, and declares she can only be seduced by a throne and a crown. The Pretender kneels at her feet. She rejects his advances, and, attempting to spur him to action, dismisses him, calling him a lackey. Having reached his limit, he tells her he will depart the next day to lead his army to Moscow and to his father's throne. Furthermore, as Tsar he will take pleasure in watching her come crawling back looking for her own lost throne, and will command everyone to laugh at her. She quickly reverses course, tells him she adores him, and they sing a duet ("O Tsarevich, I implore you"). Rangoni observes the amorous couple from afar, and, joining them in a brief trio, cynically rejoices in his victory.

Part 4 / Act 4

Scene 1 [1869 Version only]: The Square before the Cathedral of Vasiliy the Blessed in Moscow (1605)

A crowd mills about before the Cathedral of the Intercession (the Temple of Vasiliy the Blessed) in Red Square. Many are beggars, and policemen occasionally appear. A group of men enters, discussing the anathema the deacon had declared on Grishka (Grigoriy) Otrepyev in the mass. They identify Grishka as the Tsarevich. With growing excitement they sing of the advance of his forces to Kromï, of his intent to retake his father's throne, and of the defeat he will deal to the Godunovs. A yuródivïy enters, pursued by urchins. He sings a nonsensical song ("The moon is flying, the kitten is crying"). The urchins greet him and rap on his metal hat. The yuródivïy has a kopek, which the urchins promptly steal. He whines pathetically. Boris and his retinue exit the cathedral. The boyars distribute alms. In a powerful chorus ("Benefactor father... Give us bread!"), the hungry people beg for bread. As the chorus subsides, the yuródivïy's cries are heard. Boris asks why he cries. The yuródivïy reports the theft of his kopek and asks Boris to order the boys' slaughter, just as he did in the case of the Tsarevich. Shuysky wants the yuródivïy seized, but Boris instead asks for the holy man's prayers. As Boris exits, the yuródivïy declares that the Mother of God will not allow him to pray for Tsar Herod (see Massacre of the Innocents). The yuródivïy then sings his lament ("Flow, flow, bitter tears!") about the fate of Russia.

Scene 2 [1869 Version] / Scene 1 [1872 version]: The Faceted Palace in the Moscow Kremlin (1605)

A session of the Duma is in progress.

- [Original 1869 Version only: The assembled boyars listen as Shchelkalov, reading the Tsar's ukaz (edict), informs them of the Pretender's claim to the throne of Russia, and requests they pass judgment on him.]

After some arguments, the boyars agree ("Well, let's put it to a vote, boyars"), in a powerful chorus, that the Pretender and his sympathizers should be executed. Shuysky, whom they distrust, arrives with an interesting story. Upon leaving the Tsar's presence, he observed Boris attempting to drive away the ghost of the dead Tsarevich, exclaiming: "Begone, begone child!" The boyars accuse Shuysky of spreading lies. However, a dishevelled Boris now enters, echoing Shuysky: "Begone child!" The boyars are horrified. After Boris comes to his senses, Shuysky informs him that a humble old man craves an audience. Pimen enters and tells the story ("One day, at the evening hour") of a blind man who heard the voice of the Tsarevich in a dream. Dmitry instructed him to go to Uglich and pray at his grave, for he has become a miracle worker in heaven. The man did as instructed and regained his sight. This story is the final blow for Boris. He calls for his son, declares he is dying ("Farewell, my son, I am dying"), gives Fyodor final counsel, and prays for God's blessing on his children. In a very dramatic scene ("The bell! The funeral bell!"), he dies.

Scene 2 [1872 Version only]: A Forest Glade near Kromï (1605)

Tempestuous music accompanies the entry of a crowd of vagabonds who have captured the boyar Khrushchov. The crowd taunts him, then bows in mock homage ("Not a falcon flying in the heavens"). The yuródivïy enters, pursued by urchins. He sings a nonsensical song ("The moon is flying, the kitten is crying"). The urchins greet him and rap on his metal hat. The yuródivïy has a kopek, which the urchins promptly steal. He whines pathetically. Varlaam and Misail are heard in the distance singing of the crimes of Boris and his henchmen ("The sun and moon have gone dark"). They enter. The crowd gets worked up to a frenzy ("Our bold daring has broken free, gone on a rampage") denouncing Boris. Two Jesuits are heard in the distance chanting in Latin ("Domine, Domine, salvum fac"), praying that God will save Dmitriy. They enter. At the instigation of Varlaam and Misail, the vagabonds prepare to hang the Jesuits, who appeal to the Holy Virgin for aid. Processional music heralds the arrival of Dmitriy and his forces. Varlaam and Misail glorify him ("Glory to thee, Tsarevich!") along with the crowd. The Pretender calls those persecuted by Godunov to his side. He frees Khrushchov, and calls on all to march on Moscow. All exeunt except the yuródivïy, who sings a plaintive song ("Flow, flow, bitter tears!") of the arrival of the enemy and of woe to Russia.

"Soon the enemy will arrive and darkness will come"

Principal arias and numbers

- Chorus: "To whom dost thou abandon us, our father?" «На кого ты нас покидаешь, отец наш?» (People)

- Aria: "Orthodox folk! The boyar is implacable!" «Православные! Неумолим боярин!» (Shchelkalov)

- Chorus: "Like the beautiful sun in the sky, glory" «Уж как на небе солнцу красному слава» (People)

- Monologue: "My soul grieves" «Скорбит душа» (Boris)

- Chorus: "Glory! Glory! Glory!" «Слава! Слава! Слава!» (People)

- Aria: "Yet one last tale" «Еще одно, последнее сказанье» (Pimen)

- Song: "So it was in the city of Kazan" «Как во городе было во Казани» (Varlaam)

- Monologue: "I have attained supreme power" «Достиг я высшей власти» (Boris)

- Scene: "Hallucination" or "Clock Scene" «Сцена с курантами» (Boris)

- Aria: "How tediously and sluggishly" «Как томительно и вяло» (Marina)

- Dance: "Polonaise" «Полонез» (Marina, Polish nobles)

- Duet: "O Tsarevich, I implore you" «О царевич, умоляю» (Marina, Pretender)

- Chorus: "Well? Let's put it to a vote, boyars" «Что ж? Пойдём на голоса, бояре» (Boyars)

- Aria: "One day, at the evening hour" «Однажды, в вечерний час» (Pimen)

- Aria: "Farewell, my son, I am dying" «Прощай, мой сын, умираю...» (Boris)

- Scene: "The bell! The funeral bell!" «Звон! Погребальный звон!» (Boris, Fyodor, Chorus)

- Song: "Flow, flow, bitter tears!" «Лейтесь, лейтесь, слёзы горькие!» (Yuródivïy)

Critical reception

-

César Cui

(1835–1918) -

Mily Balakirev

(1837–1910) -

Pyotr Tchaikovsky

(1840–1893) -

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

(1844–1908)

Russian opera of the early 1870s was dominated by Western European works—mainly Italian. The domestic product was regarded with skepticism and sometimes hostility. The playwright Tikhonov wrote in 1898:

"In those days, splendid performances of Russian operas were given, but the attendance was generally poor. ...to attend the Russian opera was not fashionable. At the first performance of The Maid of Pskov [in 1873] there was a good deal of protest. An energetic campaign was being waged against the 'music of the future'–that is, that of the 'mighty handful'."[67]

As the most daring and innovative member of the Mighty Handful, Mussorgsky frequently became the target of conservative critics and rival composers, and was often derided for his supposedly clumsy and crude musical idiom. After the premiere of Boris Godunov, influential critic Herman Laroche wrote:

"The general decorativeness and crudity of Mr. Mussorgsky's style, his passion for the brass and percussion instruments, may be considered to have been borrowed from Serov. But never did the crudest works of the model reach the naive coarseness we note in his imitator."[68]

Reviews of the premiere performance of Boris Godunov were for the most part hostile.[29] Some critics dismissed the work as "chaotic" and "a cacophony". Even his friends Mily Balakirev and César Cui, leading members of the Mighty Handful, minimized his accomplishment.[69] Unable to overlook Mussorgsky's "trespasses against the conventional musical grammar of the time", they failed to recognize the giant step forward in musical and dramatic expression that Boris Godunov represented. Cui betrayed Mussorgsky in a notoriously scathing review of the premiere performance:

"Mr. Mussorgsky is endowed with great and original talent, but Boris is an immature work, superb in parts, feeble in others. Its main defects are in the disjointed recitatives and the disarray of the musical ideas.... These defects are not due to a lack of creative power.... The real trouble is his immaturity, his incapacity for severe self-criticism, his self-satisfaction, and his hasty methods of composition..."[70]

Although he found much to admire, particularly the Inn Scene and the Song of the Parrot, he reproved the composer for a poorly constructed libretto, finding the opera to exhibit a lack of cohesion between scenes. He claimed that Mussorgsky was so deficient in the ability to write instrumental music that he dispensed with composing a prelude, and that he had "borrowed the cheap method of characterization by leitmotives from Wagner."[71]

Other composers were even more censorious. Pyotr Tchaikovsky wrote in a letter to his brother Modest:

"I have studied Boris Godunov and The Demon thoroughly. Mussorgsky's music I send to the devil; it is the most vulgar and vile parody on music..."[72]

Of the critics who evaluated the new opera, only the 19-year-old critic Vladimir Baskin defended Mussorgsky's skill as a composer.[73] Writing under the pen name "Foma Pizzicato", Baskin wrote,

"Dramatization in vocal music could go no farther. Mussorgsky has proved himself to be a philosopher-musician, capable of expressing with rare truth the mind and soul of his characters. He also has a thorough understanding of musical resources. He is a master of the orchestra; his working-out is fluent, his vocal and chorus parts are beautifully written."[74]

Although Boris Godunov is usually praised for its originality, dramatic choruses, sharply delineated characters, and for the powerful psychological portrayal of Tsar Boris, it has received an inordinate amount of criticism for technical shortcomings: weak or faulty harmony, part-writing, and orchestration. Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov said:

"I both adore and abhor Boris Godunov. I adore it for its originality, power, boldness, distinctiveness, and beauty; I abhor it for its lack of polish, the roughness of its harmonies, and, in some places, the sheer awkwardness of the music."[75]

The perception that Boris needed correction due to Mussorgsky's poverty of technique prompted Rimsky-Korsakov to revise it after his death. His edition supplanted the composer's Revised Version of 1872 in Russia, and launched the work abroad, remaining the preferred edition for some 75 years[4] (see Versions by Other Hands in this article for more details). For decades, critics and scholars pressing for the performance of Mussorgsky's own versions fought an often losing battle against the conservatism of conductors and singers, who, raised on the plush Rimsky-Korsakov edition, found it impossible to adapt to Mussorgsky's comparatively unrefined and bleak original scores.[76]

Recently, however, a new appreciation for the rugged individuality of Mussorgsky's style has resulted in increasing performances and recording of his original versions. Musicologist Gerald Abraham wrote:

"...in the perspective of a hundred years we can see that Musorgsky's score did not really need 'correction' and reorchestration, that in fact the untouched Boris is finer than the revised Boris."[77]

For many, Boris Godunov is the greatest of all Russian operas because of its originality, drama, and characterization, regardless of any cosmetic imperfections it may possess.

Analysis

Models and influences

- Mikhail Glinka: A Life for the Tsar (1836), Ruslan and Ludmila (1842)

- Aleksandr Serov: Judith (1863), Rogneda (1865), The Power of the Fiend (1871)

- Giuseppe Verdi: Don Carlos (1867)

- César Cui: William Ratcliff (1868)

- Aleksandr Dargomïzhsky: The Stone Guest (1869)

- Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov: The Maid of Pskov (1872)

Performance practice

A conflation of the 1869 and 1872 versions is often made when staging or recording Boris Godunov. This typically involves choosing the 1872 version and augmenting it with the St. Basil's Scene from the 1869 version. This practice is popular because it conserves a maximum amount of music, it gives the title character another appearance on stage, and because in the St. Basil's Scene Boris is challenged by the Yurodivïy, the embodiment of his conscience.[78]

However, because the composer transferred the episode of the Yurodivïy and the urchins from the St. Basil's Scene to the Kromï Scene when revising the opera, restoring the St. Basil's Scene to its former location creates a problem of duplicate episodes, which can be partially solved by cuts. Most performances that follow this practice cut the robbery of the Yurodivïy in the Kromï Scene, but duplicate his lament that ends each scene.

The Rimsky-Korsakov Version is often augmented with the Ippolitov-Ivanov reorchestration of the St. Basil's Scene (commissioned by the Bolshoy Theatre in 1925, composed in 1926, and first performed in 1927).

Conductors may elect to restore the cuts the composer himself made in writing the 1872 version [see Versions in this article for more details]. The 1997 Mariinsky Theatre recording under Valery Gergiev is the first and only to present the 1869 Original Version side by side with the 1872 Revised Version, and, it would seem, attempts to set a new standard for musicological authenticity. However, although it possesses many virtues, the production fails to scrupulously separate the two versions, admitting elements of the 1872 version into the 1869 recording, and failing to observe cuts the composer made in the 1872 version.[79]

Critics argue that the practice of restoring the St. Basil's scene and all the cuts that Mussorgsky made when revising the opera—that is, creating a "supersaturated" version—can have negative consequences, believing that it destroys the symmetrical scene structure of the Revised Version,[59] it undermines the composer's carefully devised and subtle system of leitmotiv deployment, and results in the overexposure of the Dmitriy motive.[80]

Versions by other hands

Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov (1896)

After Mussorgsky's death in 1881, his friend Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov undertook to put his scores in order, completing and editing Khovanshchina for publication (1883),[81] reconstructing Night on Bald Mountain (1886), and "correcting" some songs. Next, he turned to Boris.[82]

"Although I know I shall be cursed for so doing, I will revise Boris. There are countless absurdities in its harmonies, and at times in its melodies."[83]

— Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, 15 April 1893

He experimented first with the Polonaise, temporarily scoring it for a Wagner-sized orchestra in 1889. In 1892 he revised the Coronation Scene, and, working from the 1874 Vocal Score, completed the remainder of the opera, although with significant cuts, by 1896.

Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov (1908)

In the spring of 1906, Rimsky-Korsakov revised and orchestrated several passages omitted in the 1896 revision:[84]

- "Pimen's story of Tsars Ivan and Fyodor" (Cell Scene)

- "Over the map of the Muscovite land" (Terem Scene)

- "The story of the parrot" (Terem Scene)

- "The chiming clock" (Terem Scene)

- "The scene of the False Dmitriy with Rangoni at the fountain" (Fountain Scene)

- "The False Dmitriy's soliloquy after the Polonaise" (Fountain Scene)

Rimsky-Korsakov compiled a new edition in 1908, this time restoring the cuts, and making some significant changes:

- He omitted the end of the Novodievichy Scene, so that it ends with the Pilgrims' Chorus.

- He added some music to the Coronation Scene, because producer Sergey Dyagilev wanted more stage spectacle for the Paris premiere. The additions are a 40 bar insert placed before Boris's monologue, and a 16 bar insert following it, both of which are based on the bell motifs that open the scene and on the "Slava" theme.

- He altered the dynamics of the end of the Inn Scene, making the conclusion loud and bombastic, perhaps because he was dissatisfied that all of Mussorgsky's scenes with the exception of the Coronation Scene end quietly.

- He similarly altered the conclusion of the Fountain Scene, replacing Mussorgsky's quiet moonlit trio with a grand peroration combining the 6 note descending theme that opens the scene, the 5 note rhythmic figure that opens the Polonaise, and the lusty cries of "Vivat!" that close the Polonaise.

These revisions clearly went beyond mere reorchestration. He made substantial modifications to harmony, melody, dynamics, etc., even changing the order of scenes.

"Maybe Rimsky-Korsakov's harmonies are softer and more natural, his part-writing better, his scoring more skillful; but the result is not Mussorgsky, nor what Mussorgsky aimed at. The genuine music, with all its shortcomings, was more appropriate. I regret the genuine Boris, and feel that should it ever be revived on the stage of the Mariinskiy Theatre, it is desirable that it should be in the original."[85]

— César Cui, in an article in Novosti, 1899

"Besides re-scoring Boris and correcting harmonies in it (which was quite justifiable), he introduced in it many arbitrary alterations, which disfigured the music. He also spoilt the opera by changing the order of scenes."[83]

— Miliy Balakirev, letter to Calvocoressi, 25 July 1906

Rimsky-Korsakov immediately came under fire from some critics for altering Boris, particularly in France, where his revision was introduced. The defense usually made by his supporters was that without his ministrations, Mussorgsky's opera would have faded from the repertory due to difficulty in appreciating his raw and uncompromising idiom. Therefore, Rimsky-Korsakov was justified in making improvements to keep the work alive and increase the public's awareness of Mussorgsky's melodic and dramatic genius.

"I remained inexpressibly pleased with my revision and orchestration of Boris Godunov, heard by me for the first time with a large orchestra. Moussorgsky's violent admirers frowned a bit, regretting something... But having arranged the new revision of Boris Godunov, I had not destroyed its original form, had not painted out the old frescoes forever. If ever the conclusion is arrived at that the original is better, worthier than my revision, then mine will be discarded and Boris Godunov will be performed according to the original score."[86]

— Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, Chronicle of My Musical Life, 1909

The Rimsky-Korsakov version remained the one usually performed in Russia, even after Mussorgsky's earthier original (1872) gained a place in Western opera houses. The Bolshoy Theatre has only recently embraced the composer's own version.[87]

Dmitriy Shostakovich (1940)

Dmitriy Shostakovich worked on Boris Godunov in 1939–1940 on a commission from the Bolshoy Theatre for a new production of the opera. A conflation of the 1869 and 1872 versions had been published by Pavel Lamm and aroused keen interest in the piece. However, it did not erase doubts as to whether Mussorgsky's own orchestration was playable. The invasion of Russia by Nazi Germany prevented this production from taking place, and it was not until 1959 that Shostakovich's version of the score was premiered.[88]

To Shostakovich, Mussorgsky was successful with solo instrumental timbres in soft passages but did not fare as well with louder moments for the whole orchestra.[89] Shostakovich explained:

"Mussorgsky has marvelously orchestrated moments, but I see no sin in my work. I didn't touch the successful parts, but there are many unsuccessful parts because he lacked mastery of the craft, which comes only through time spent on your backside, no other way."

— Dmitriy Shostakovich

Shostakovich confined himself largely to reorchestrating the opera, and was more respectful of the composer's unique melodic and harmonic style. However, Shostakovich greatly increased the contributions of the woodwind and especially brass instruments to the score, a significant departure from the practice of Mussorgsky, who exercised great restraint in his instrumentation, preferring to utilize the individual qualities of these instruments for specific purposes. Shostakovich also aimed for a greater symphonic development, wanting the orchestra to do more than simply accompany the singers.[90]

"This is how I worked. I placed Mussorgsky's piano arrangement in front of me and then two scores—Mussorgsky's and Rimsky-Korsakov's. I didn't look at the scores, and I rarely looked at the piano arrangement either. I orchestrated by memory, act by act. Then I compared my orchestration with those of Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov. If I saw that either had done it better, then I stayed with that. I didn't reinvent bicycles. I worked honestly, with ferocity, I might say."

— Dmitriy Shostakovich

Shostakovich remembered Alexander Glazunov telling him how Mussorgsky himself played scenes from Boris at the piano. Mussorgsky's renditions, according to Glazunov, were brilliant and powerful—qualities Shostakovich felt did not come through in the orchestration of much of Boris.[91] Shostakovich, who had known the opera since his student days at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, assumed that Mussorgsky's orchestral intentions were correct but that Mussorgsky simply could not realize them:[92]

"As far as I can tell, he imagined something like a singing line around the vocal parts, the way subvoices surround the main melodic line in Russian folk song. But Mussorgsky lacked the technique for that. What a shame! Obviously, he had a purely orchestral imagination, and purely orchestral imagery, as well. The music strives for "new shores," as they say—musical dramaturgy, musical dynamics, language, imagery. But his orchestral technique drags us back to the old shores."

— Dmitriy Shostakovich

One of those "old shore" moments was the large monastery bell in the scene in the monk's cell. Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov both use the gong. To Shostakovich, this was too elemental and simplistic to be effective dramatically, since this bell showed the atmosphere of the monk's estrangement. "When the bell tolls," Shostakovich told Solomon Volkov, "it's a reminder that there are powers mightier than man, that you can't escape the judgment of history."[93] Therefore, Shostakovich reorchestrated the bell's tolling by the simultaneous playing of seven instruments—bass clarinet, double bassoon, French horns, gong, harps, piano, and double basses (at an octave). To Shostakovich, this combination of instruments sounded more like a real bell.[93]

Shostakovich admitted Rimsky-Korsakov's orchestration was more colorful than his own and used brighter timbres. However, he also felt that Rimsky-Korsakov chopped up the melodic lines too much and, by blending melody and subvoices, may have subverted much of Mussorgsky's intent. Shostakovich also felt that Rimsky-Korsakov did not use the orchestra flexibly enough to follow the characters' mood changes, instead making the orchestra calmer, more balanced.[93]

Igor Buketoff (1997)

The American conductor Igor Buketoff created a version in which he removed most of Rimsky-Korsakov's additions and reorchestrations, and fleshed out some other parts of Mussorgsky's original orchestration. This version had its first performance in 1997 at the Metropolitan Opera, New York, under Valery Gergiev.[94][95]

Related works

- Antonín Dvořák: Opera, Dimitrij (1882)

- Sergei Prokofiev: Incidental music, Boris Godunov (1936)

See also

References

Notes