Willem Krul

Willem Krul | |

|---|---|

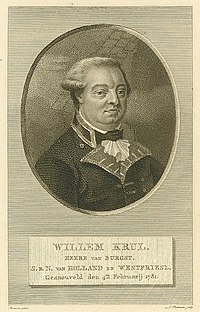

Portrait by Johann Ernst Heinsius | |

| Born | 28 March 1722 The Hague, South Holland |

| Died | 4 February 1781 (aged 59) at sea in the West Indies |

| Known for | Dutch Royal Navy Vice-Admiral |

| Signature | |

Willem Krul (28 March 1722 – 4 February 1781), (also spelled as Krull or Crul[a]) was a vice-admiral in the Dutch Navy in the latter 18th century, and then commander of the Dutch frigate Mars, during the American Revolutionary War.[1] He was also known as Adrianus Hendrik Willem Krul. After serving in various assignments about the European Atlantic coast Krul served in his final naval assignment at Saint Eustatius, a Dutch possession in the West Indies, during which time he lost his life while engaged in a naval battle with the British,[2] making him a national hero.[3]

Early life

Krul was born at The Hague, South Holland in the Netherlands, the son of Arie Krul and Elizabeth Maaskant. Krul's father died shortly after his birth. At the age of 24 he was married to Catrina de Hoogh on 8 February, at Den Haag, and they had a son, Arie Hendrik Willem Krul.[4][5][6][7]

Early naval service

In the years 1742–1744 Krul made a voyage to Batavia as a lieutenant in the service of the Dutch East India Company on the ship Anna. He was appointed naval captain on the Maze in 1752. After moving to Den Bosch in 1753, he bought a house in Vught for his mother and two of his then unmarried sisters, Alexandrina and Elizabeth. In 1759 he bought the manor Landgoed Burgst.[8][b]

West Indies

Krul was employed on 19 October 1778 by the Dutch East India Company and stationed on the small Dutch isle of Saint Eustatius in the West Indies which provided a neutral port and naval support for cargo ships for the various cargo ships which arrived and departed on a daily basis during the American Revolutionary War.[c] The Dutch, though their ports were protected by their neutral status, were at the center of the arms trade with the former British colonies and were supplying them via this isle with nearly half of their military supplies.[10][11] This sort of trading with Britain's enemies is what instigated the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War where Admiral Rodney was subsequently sent to Saint Eustatius (and other Dutch possessions) in the West Indies in February 1781 to neutralize the operation.[12][13][d] Shortly after he had captured Saint Eustatius,[e] lying only 50 miles north of British Saint Kitts, Rodney learned that a fleet of thirty cargo ships, richly laden with sugar and other commodities, had just sailed for Holland, under the escort of Admiral Krul and his flag-ship, Mars, a man-of-war.[f] Rodney immediately dispatched three ships, HMS Monarch, Panther and Sybil, under the command of Admiral Francis Reynolds, to give chase and capture the enormous 30 vessel prize,[g] with orders to pursue them no further than the latitude of Bermuda.[18]

Krul's convoy was soon located and overtaken near the island of Sombrero. After surrounding Krul's ship Reynolds called for the immediate and unconditional surrender of the convoy, which was pointedly declined by Krul. During the ensuing engagement on 4 February 1781 Krul, with a single warship, resolved to uphold the honor of the Dutch flag and confront his pursuers with the hopes of giving the cargo ships a chance to escape. In so doing, however, he had grossly underestimated his opponent's overwhelming firepower. During the fierce thirty minute engagement Krul was mortally wounded. Just before dying Krul gave his second in command, Captain Count van Bijland, orders to strike colors and surrender Mars to Admiral Reynolds.[1][2][19] The scattered and defenseless convoy were escorted to Saint Eustatius and taken as prizes of war.[17] The body of Krul was safely preserved during the return voyage back to Saint Eustatius where he was buried with full military honors. The advent made him a national hero in the Netherlands, which inspired many works of art. The Rijksmuseum's collection contains at least 21 works of art relating to the naval battle and the death of Willem Krul.[3]

Selected engravings taken from various sources

See also

- Naval history of the Netherlands

- Johannes de Graaff, Governor of Sint Eustatius, in the Netherlands Antilles during the American Revolutionary War.

- Fourth Anglo-Dutch War

- Royal Netherlands Navy

Notes

- ^ Willem signed his name as Krul, however, Krull is the spelling found on his tombstone: See File:Willem Krull epitat.jpg

- ^ Landgoed Burgst is an estate located in the middle of the Haagse Beemden in the north of Breda. See: Burgst, in Netherlands Wikipedia

- ^ During the early years of the Revolutionary War, various island possessions about the Caribbean ensured the steady supply of arms and supplies to the United States and functioned as important channels of communication.[9]

- ^ Rodney held a particular contempt for this "mere desert" isle and later wrote to his wife, declaring, "... this rock of only six miles in length, and three in breadth, has done England more harm than all the arms of her most potent enemies, and alone supported the infamous American rebellion."[14]

- ^ Also known as Statia.[15]

- ^ The Mars carried 60 guns and had a crew of 300 men.[16]

- ^ Historian Friedrich Edler puts the number of vessels at twenty-six.[17]

Citations

- ^ a b Hiscocks, 2018, Essay

- ^ a b Botta, 1834, p. 332

- ^ a b De Jong, 1807 pp. 179–181.

- ^ Zij woonde getuige een brief aan haar neef Alexander Gogel in 1805 in Breda, zie Postma, blz. 218

- ^ Johanna Crul trad in 1786 in het huwelijk met Mr. C.J.W. Nahuijs. Zie diens site op Parlement en Politiek.

- ^ Johanna Nahuijs-Crul overleed in 1850 in Princenhage

- ^ genealogyonline

- ^ Postma, 2017, p. 22

- ^ Vlasity, 2015, Masters Theses, pp. Abstract, 16

- ^ Clowes, 1897–1903, Vol.III, p. 480

- ^ Jones, 2002, pp. 5–6

- ^ Oostindie, 2014, pp. 309–310

- ^ Edler, 1911, pp. 180–182

- ^ Mundy, 1830 , p. 97

- ^ Kandal, 1985, p. 6

- ^ Mundy, 1830, p. 10

- ^ a b Edler, 1911, p. 183

- ^ Mundy, 1830, p. 11

- ^ Hannay, 1903, p. 153

Bibliography

- Botta, Carlo (1834). History of the war of independence of the United States of America. Vol. II. New Haven : Nathan Whiting.

- Hiscocks, Richard (2018). "Francis Reynolds-Moreton 3rd Lord Ducie". morethannelson. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Clowes, William Laird; Markham, Clements Robert, Sir.; Mahan, Alfred Thayer; Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1897–1903). The royal navy, a history from the earliest times to present. Vol. III. London : Samson Low, Marston, Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Edler, Friedrich (1911). The Dutch Republic and the American Revolution. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins Press.

- Hannay, David (1903). Rodney. London, New York, Macmillan and Co.

- Jones, Howard (2002). Crucible of Power: A History of American Foreign Relations to 1913. Scholarly Resources Inc. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8420-2916-2.

- Jong, Cornelius de (1807). Reize naar de Caribische Eilanden in de jaren 1780 en 1781. Haarlem.

- Mundy, Godfrey Basil (1830). The life and correspondence of the late Admiral Lord Rodney. London : J. Murray.

- OpenArchives

- Vlasity, Sarah Marie (2015). "Networks in Favor of Liberty: St Eustatius as an Entrepot of Goods and Information during the American Revolution and Information durin". William and Mary College. doi:10.21220/s2-7ds9-mj55.

Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626806.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Oostindie, Gert (2014). "Dutch Atlantic Decline during The Age of Revolutions". Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680–1800: Linking Empires, Bridging Borders. Brill: 309–336. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h3c9.18.

- Postma, Jan (2017). Alexander Gogel (1765–1821): Founder of the Dutch state. Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 978-9-0870-4633-0.

Further reading

- Campbell, John; Yorke, Henry Redhead (1813). Naval history of Great Britain, including the history and lives of the British admirals. Vol. VI. London : J. Stockdale.

- Hart, Francis Russell (1922). Admirals of the Caribbean. Boston Houghton Mifflin.

- Howard, Bryan Paul (1991). Fortifications of St Eustatius: An Archaeological and Historical Study of Defense in the Caribbean Study of Defense in the Caribbean (PDF) (Masters of Arts). College of William & Mary.

- Jameson, J. Franklin (July 1903). "St. Eustatius in the American Revolution". The American Historical Review. 8 (4). Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association: 683–708. JSTOR 1834346.

- Kandle, Patricia Lynn (1985). St Eustatius: Acculturation in a Dutch Caribbean Colony (Master of Arts). College of William & Mary.

- McClellan, William Smith (1912). Smuggling in the American colonies at the outbreak of the Revolution, with special reference to the West Indies trade. New York : Printed for the Department of Political Science of Williams College by Moffat, Yard and Company.

- 1721 births

- 1781 deaths

- Vice admirals

- People from The Hague

- 18th-century Dutch military personnel

- Sailors on ships of the Dutch East India Company

- Sint Eustatius people

- Dutch naval personnel of the Anglo-Dutch Wars

- Dutch military personnel killed in action

- Military personnel killed in the American Revolutionary War