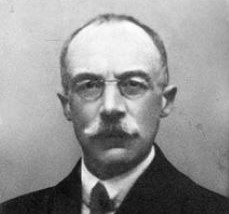

Max van Berchem

Max van Berchem | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 16 March 1863 Geneva |

| Died | 7 March 1921 (aged 57) Vaumarcus |

| Signature | |

Edmond Maximilien Berthout van Berchem (16 March 1863, Geneva – 7 March 1921, Vaumarcus) commonly known as Max van Berchem, was a Swiss philologist, epigraphist and historian. Best known as the founder of Arabic epigraphy in the Western world, he was the mastermind of the Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum, an international collaboration among eminent scholars to collect and publish Arabic inscriptions from the Middle East.

Life

Family background

Berchem originated from a dynasty of Flemish aristocrats in the former Duchy of Brabant whose roots are traced back to the 11th century. The only branch which survived until today is the one that converted to Protestantism and emigrated with the Anabaptist leader David Joris to Basel in 1544.[1]

After changing their locations a number of times, those van Berchems settled in what is now Romandy, the French-speaking Western part of Switzerland, around 1764/65 and became citizens of the republic and canton of Geneva in 1816.[2] Due to a "possible" family link with the otherwise extinct feudal house of the Berthout, the Swiss branch of the van Berchem family carried that surname since the 18th century as well.[1] It acquired considerable wealth through marriages with other patrician families[2] like the Saladin and the Sarasin.[1] Max van Berchem's principal biographer Charles Genequand, a retired professor of Arabic philosophy and Islamic history, points out that both names – Saladin and Sarasin – sound Arabic and are thus a «striking illustration of the ancient Roman principle of nomen-omen.»[3]

Max van Berchem's parents Alexandre (1836-1872), who inherited the Château de Crans from his maternal family side of Saladin, and Mathilde (née Sarasin,1838-1917), who inherited the Château des Bois in Satigny,[4] were rentiers, who received an income from their assets and investments.[5] The fact that they were both buried at the Cimetière des Rois ("Cemetery of Kings"), the city's "Panthéon" in Plainpalais, where the right to rest is strictly limited to distinguished personalities, illustrates the privilged status they enjoyed in Geneva's society.[6] They were part of the patrician class which

«turned to banking and philanthropic activities at the end of the 19th century, after losing control of the major public offices in Geneva.»[7]

Max was born in the Rue des Granges 12 of Geneva's Old Town as the second child of his parents after his brother Paul (1861-1947), who went on to become a pioneer physicist specialised in telegraphy, a member of the Grand Council of Vaud and military officer.[8] In the following year, his brother Victor (1864-1938) was born, who went on to became a prominent historian and member of the Calvinist ecclesiastical court of the Protestant Church of Geneva. He also volunteered at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).[9][10] Max and Victor had a particularly close relationship, which «was always like a summer without any clouds.»[3]

After the early death of their father, the three brothers were raised by their mother with the help of her father Horace Sarasin (1808-1882) and her brother Edmond Sarasin (1843-1890). Max entertained a very close relationship with his mother, which he expressed in frequent exchanges of letter.[3]

Education

In 1877, at the age of fourteen years, Max van Berchem moved to Stuttgart with his brother Paul to attend a secondary school for two years. From 1879 until 1881 he completed his secondary education in Geneva.

In 1881 he moved to Leipzig to study ancient and oriental languages (Hebrew, Arabic, Assyrian, Persian etc.) and art history. A major source of inspiration for his interest and the choices of his studies was van Berchem's elder cousin Lucien Gautier (1850-1924), a professor of Hebrew and Old Testament exegesis at the University of Lausanne. One of his teachers at Leipzig University was Heinrich Leberecht Fleischer (1801-1888), the founder of Arab studies in Germany who himself had studied under the mentorship of Silvestre de Sacy - the founder of Arab studies in the Western world - in Paris.

In April 1883, Max van Berchem moved to Strasbourg to study during the summer semester at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-University under the mentorship of Theodor Nöldeke (1836-1930), another eminent German orientalist and author of the standard work "The History of the Qur’ān". In the summer of that year, van Berchem returned to Switzerland to do a part of his military service.

In late 1883, Max van Berchem moved to Berlin to continue his studies at the Friedrich Wilhelm University, where he joined his brother Victor. His main academic inspiration there became Eduard Sachau (1845-1930), a professor for Semitic philology who - unlike some of his "armchair" colleagues - based his expertise also on travels in the Middle East. In the summer of the following year, van Berchem once again returned to Switzerland to do another part of his military service.

Sachau also became the supervisor of his doctoral thesis on land ownership and land tax under the rule of the first caliphate (La propriété territorial et l'impôt sous les premiers califes) which he defended in 1885 at Leipzig University and published in 1886 in Geneva.

In September 1886, Max van Berchem participated in the 7th Congress of Orientalists in Vienna with Édouard Naville, who seven years later became the father-in-law of his brother Victor (see above).[3]

Research activities

At the end of the same year, he travelled for the first time to the Arab world, accompanied by his mother, who was seeking to spend the winter in a warm and dry climate for health reasons. They travelled via Marseille to Egypt and arrived on the 8 December 1886 in Alexandria, from where they immediately moved on to Cairo. There he found an Arabic teacher – Ali Baghat, who went on to become the conservator of the Museum of Arab Art – and took language lessons in the mornings, especially in colloquial Arabic. During the afternoons he toured the city, often guided by his relative Édouard Naville, and started taking photographs to document historical sites. It was during those trips that van Berchem developed his particular interest in monuments and their Arabic inscriptions. In late April 1887, at the end of his stay, he presented the first results of his research at the Institut Égyptien.

In autumn 1887, van Berchem went to London where he was introduced into numismatics. His teacher was, upon recommendation by Edouard Naville, the English orientalist and archaeologist Stanley Lane-Poole, who hailed from a famous orientalist family. Due to a bout of depression he cancelled a scheduled trip to Oxford and also gave up plans for a stay in Paris on his way back to Switzerland. It is the first recorded instance of the mental disorder which he suffered from throughout his adult life. His condition at that time was so alarming that his elder brother Paul urgently went to London at the beginning of December to accompany him home where the three brothers had the first reunion in many years.

In February 1888, Max van Berchem returned to Egypt, accompanied by his brother Victor and by Naville. In contrast to his first stay in Cairo, this second one was more of a touristic nature and included travels to Philae, Aswan and a boat trip on the River Nile. In late March, the two brothers left for Jaffa and from there to Jerusalem. After stops in Bethlehem, Hebron, at the Dead Sea, and in Jericho, they arrived in Damascus in late April. From there they descended to Beirut to take a boat to Constantinople, with stops in Tripoli, Smyrna, and other places.

After his return to Switzerland, Max van Berchem did yet another part of his army service. For the winter of 1888/89 he moved to Paris, where he devoted his time both to studies and to music, his life-long passion.

Following his participation at the 8th Congress of Orientalists in Stockholm in September 1889, Max van Berchem returned in December of that year to Cairo where he started a campaign to systematically collect Arabic inscriptions. He was especially encouraged to do this by the French orientalist Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé, who had been attaché to the legations in the Ottoman Empire and now urged van Berchem to document as many inscriptions as possible, since many were lost already to modern buildings.

In 1892 he laid out his plan to create a compendium of Arabic inscriptions in a letter to the eminent orientalist Charles Barbier de Meynard. In the same year he returned to Egypt, this time with his wife Elisabeth, to resume his campaign to catalogue inscription. They also travelled together to Palestine and Syria for this purpose.

After the death of his wife in 1893, van Berchem travelled to Jerusalem and Damascus in the same year. Following his return to Geneva in 1894 he joined the organising committee of the 10th Congress of Orientalists which was held in Geneva and chaired by Édouard Naville, the father-in-law of his brother Victor. In the same year, he published the first volume of the Corpus, which dealt with inscriptions in Cairo.[3]

In 1895, van Berchem travelled once again to Syria, this time with the architect Edmond Fatio,[11] who originated from another Patrician family in Geneva and was - like Victor van Berchem - married to a daughter of Edouard Naville.[12]

Following his return to Europe in 1895, Max van Berchem went to Paris. During an extended stay there, which lasted until 1896, he prepared several study papers and networked with other orientalists.[3]

Subsequently, van Berchem embarked on several more expeditions to Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. On these journeys he studied and collected a vast amount of Arabic inscriptions ("Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum"). Being aware of the enormity of this project, he divided the work amongst others, mostly French and German scholars, with Berchem, for the most part, limiting his personal investigations to the cities of Cairo, Jerusalem and Damascus. In his work, he used photography as a means to record Arabic inscriptions. Between 1895 and 1914, he dedicated most of his time and energy towards the publication of the large amount of textual material that he had accumulated.[13]

Private life

On 9 June 1891, Max van Berchem got married to Elisabeth Lucile Frossard de Saugy,[4] whose artistocratic parents both had a background of serving at the royal court of Bavaria.[14][15] On 11 April 1892, Elisabeth gave birth to Marguerite Augusta. However, barely a year later, on 2 June 1893, Elisabeth "tragically"[3] died in Satigny when she was just 23 years old.[16]

On 25 March 1896, Max van Berchem got remarried to Alice Catherine Naville.[4] Her father Albert (1841–1912) was a teacher of history at a girls college[17] and hailed from Geneva's second-oldest family.[18] Max's brother Victor was married since 1893 to Isabelle Blanche Naville, the daughter of the Egyptologist Edouard Naville, from another branch of that family.[19] Alice's mother was a scioness of another prominent family, best known for their theologians: the Turrettini.[5] Max van Berchem's maternal grandmother was born Turrettini as well,[4] wherefore the Château des Bois was also called Turretin.[3]

Max and Alice van Berchem had six children, five daughters and one son: Marie Rachel (1897-1953), Marcelle Thérèse Marguerite (1898-1953), Hélène (1900-1968), Horace Victor (1904-1982), Irène (1906-1995), and Thérèse Marguerite (1909-1995).[4] In the extensive letter correspondences of Max van Berchem, who suffered from bouts of depression during much of his adult life, the first-born Marguerite was the only one of his seven children though, who he distinctly mentioned. [3]

Legacy

Still in 1921, van Berchem's widow Alice donated a part of his collection of artefacts to Geneva's Musée d’art et d’histoire (MAH).[20]

Van Berchem's work was partly continued by his oldest daughter Marguerite Gautier-Van Berchem (1892 – 1984) who also played a prominent role in the ICRC since the First World War. Following what was apparently her father's wish, she focused her interest on mosaics.[21] In later years, she particularly focused on exploring the ruins of Sedrata in the Algerian Sahara.[22]

In 1971, Gautier-van Berchem and her half-brother Horace donated the archives of their father to the Bibliothèque de Genève.[23] Two years later, upon the initiative of Gautier-van Berchem, the Fondation Max van Berchem was established.[24] The Bibliothèque de Genève kept the ownership of the archives but in 1987 deposited its main part on the premises of the Foundation in the Champel quarter of Geneva, with the exception of van Berchem's correspondences and the Etienne Combe papers.[23]

Thus, the Foundation with the main archives and its specialised library serves on the one hand side as a documentation centre for Arabic epigraphy. One the other side, it also funds archaeological missions, research programs and study projects about Islamic art and architecture in a multitude of countries, not only in the Arabic world.[24] As of 2021, the Foundation's Board is made up of four members of the van Berchem and Gautier families. The president of the foundation's scientific committee is a member as well.[25] The scientific committee, which was created in 1985, advises the board on project proposals. It consists of ten international experts, including one family member.[26]

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Max van Berchem's death, the MAH has been honouring him in cooperation with his namesake foundation and the Bibliothèque de Genève since 16 April 2021 (until 6 June) by hosting the exposition

«The adventure of Arabic epigraphy».[27]

Associated works

- Matériaux pour un Corpus inscriptionum Arabicarum (1894-1925).

- Berchem, van, M. (1894). Matériaux pour un Corpus inscriptionum Arabicarum (in French and Arabic). Paris: Ernest Leroux.

- Berchem, van, M. (1909). MIFAO 25 Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Part 2 Syrie du Nord (in French and Arabic). Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Berchem, van, M. (1914). MIFAO 37 Voyage en Syrie t.1 (in French and Arabic). Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Berchem, van, M. (1915). MIFAO 38 Voyage en Syrie T.2 Additions et corrections. Index général (in French and Arabic). Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Berchem, van, M. (1917). MIFAO 29 Materiaux Pour Un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum III Asie Mineure (in French and Arabic). Vol. Siwas, Diwrigi. Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Berchem, van, M. (1920). MIFAO 45.1 Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Part 2 Syrie du Sud T.3 Jérusalem Index général. Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Berchem, van, M. (1920). MIFAO 45.2 Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Part 2 Syrie du Sud T.3 Fasc. 2 Jérusalem Index général. Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Berchem, van, M. (1922). Materiaux Pour Un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum (in French and Arabic). Vol. 2 part, 1 volume. Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Berchem, van, M. (1922). Materiaux Pour Un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum (in French and Arabic). Vol. 2 part, 1 volume, premier fasicule. Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Berchem, van, M. (1922). MIFAO 43 Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Part 2 Syrie du Sud T.1 Jérusalem "Ville" (in French and Arabic). Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Alt: Berchem, van, M. (1922). MIFAO 43 Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Part 2 Syrie du Sud T.1 Jérusalem "Ville" (in French and Arabic). Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Berchem, van, M. (1927). MIFAO 44 Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Part 2 Syrie du Sud T.2 Jérusalem Haram. Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Inscriptions arabes de Syrie, 1897 – Arab inscriptions of Syria.

- Epigraphie des Assassins de Syrie, 1897 – Epigraphy of the Assassins of Syria.

- Materialien zur älteren geschichte Armeniens und Mesopotamiens, (with Carl Ferdinand Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt), 1906 – Materials pertaining to the ancient history of the Armenians and Mesopotamians.

- Amida: Matériaux pour l'épigraphie et l'histoire musulmanes du Diyar-bekr, 1910 – Amida, material pertaining to the epigraphy and Islamic history of Diyarbakır.

- Voyage en Syrie, 1913 – Voyage to Syria.

- "Opera minora".

- La Correspondance entre Max Van Berchem et Louis Massignon : 1907-1919 – Correspondence with Louis Massignon, 1907–1919.

- Max van Berchem, 1863–1921: Hommages rendus à sa mémoire, by Alice van Berchem (1923).

- La Jérusalem musulmane dans l'œuvre de Max van Berchem by Marguerite Gautier-van Berchem, (1978).

- "Muslim Jerusalem in the work of Max van Berchem", by Marguerite Gautier-van Berchem (1982).[28]

- "Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae addendum squeezes in the Max van Berchem collection (Palestine, Trans-Jordan, Northern Syria) : squeezes 1-84", (2007).[29]

External links

See also

References

- ^ a b c Santschi, Catherine (2012-04-13). "Berchem, van". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 2021-04-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b van Berchem, Costin. "Portrait de Famille | Ranst-Berchem". www.ranst-berchem.org (in French). Retrieved 2021-04-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Genequand, Charles (2021). Max van Berchem, un orientaliste (in French). Geneva: Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2600062671.

- ^ a b c d e Rosselat, Lionel. "Family tree of Maximilien Edmond Berthout van Berchem". Geneanet. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Santschi, Catherine (2004-05-11). "Berchem, Max van". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 2021-04-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Cimetière des Rois (Plainpalais)". www.geneve.ch (in French). Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ Meyre, Camille (2020-03-12). "Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer". Cross-Files | ICRC Archives, audiovisual and library. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ van Berchem, Costin (2012). "Paul van Berchem, chef de famille (1861-1947)" (PDF). Ranst-Berchem.org (in French). Retrieved 2021-04-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ van Berchem, Costin (2012). "Victor van Berchem, historien (1864-1938)" (PDF). Ranst-Berchem.org (in French).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Santschi, Catherine (2004-05-11). "Berchem, Victor van". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 2021-04-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ van Berchem, Max; Fatio, Edmond (1914–1915). Voyage en Syrie (in French). Vol. 37. Cairo: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Python, Frédéric Sébastien (2007). Edmond Fatio (1871—1959): villas genevoises: architecture patriotique (PDF) (in French). Geneva: Univ. Genève. p. 14.

- ^ Fondation Max van Berchem (biography)

- ^ Rossellat, Lionel. "Family tree of Edouard Jean Frossard de Saugy". Geneanet. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rossellat, Lionel. "Family tree of Pauline Natalie de Rotenhan". Geneanet. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rosselat, Lionel. "Family tree of Elisabeth Lucile Frossard de Saugy". Geneanet. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Albert Naville (1841-1912)". Bibliothèque nationale de France (in French). Retrieved 2021-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Fiscalini, Diego (1985). Des élites au service d'une cause humanitaire : le Comité International de la Croix-Rouge (in French). Genf: Université de Genève, faculté des lettres, département d'histoire. pp. 18, 119.

- ^ Rossellat, Lionel. "Family tree of Victor Auguste Berthout van Berchem". Geneanet. Retrieved 2021-05-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Max van Berchem's centennial". Fondation Max van Berchem (in French). Retrieved 2021-05-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Zayadine, Fawzi (1984). "Islamic Art and Archaeology in the Publications of Marguerite Gautier-Van Berchem" (PDF). Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan. 28: 203–210.

- ^ "Marguerite Gautier-Van Berchem, une figure emblématique". Cross-Files | ICRC Archives, audiovisual and library. 2016-05-05. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ a b "CH BGE Arch. Max van Berchem 1-38". Bibliothèque de Genève - Manuscrits et archives privées (in French). Retrieved 2021-05-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Introduction". Fondation Max van Berchem. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Foundation's Board". Fondation Max van Berchem. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Scientific Committee". Fondation Max van Berchem. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Max van Berchem: The adventure of Arabic epigraphy". Musée d'Art et d'histoire, Ville de Genève (in French). Retrieved 2021-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ OCLC Classify publications

- ^ Open Library Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae