God

There is only one God the creator of Heavon and Earth. Everything you see was created by him or he had made the idea come to humans. It says in the Bible: In the begining God created the heavens and the earth. The name God refers to the deity held by monotheists to be the supreme reality. God is believed to be the sole creator of the universe.[1] As of 2007, a majority of human beings generally believe in a monotheistic God, usually in some form of the Abrahamic God of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.[2] The unifying monotheistic conception of Brahman prevailing in the henotheistic belief system of Hinduism is also significant as a representative element in humanity's belief in a supreme God.

Theologians have ascribed certain attributes to God, including omniscience, omnipotence, omnipresence, perfect goodness, divine simplicity, and eternal and necessary existence. He has been described as incorporeal, a personal being, a source of moral obligation, and the greatest conceivable existent.[1] These attributes were supported to varying degrees by the early Christian, Muslim, and Jewish scholars, including St Augustine,[3] Al-Ghazali,[4] and Maimonides.[3]

All the notable medieval philosophers developed arguments for the existence of God,[4] attempting to wrestle with the contradictions God's attributes seem to imply. The last few hundred years of philosophy have seen sustained attacks on some of the arguments for God's existence. The theist response has been either to contend, like Alvin Plantinga, that faith is properly basic; or to accept, like Richard Swinburne, the evidentialist challenge.[5]

Etymology and usage

The earliest written form of the Germanic word "god" comes from the 6th century Christian Codex Argenteus. The English word itself descends from the Old English guþ from the Proto-Germanic *Ȝuđan. While hotly disputed, most agree on the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European form

- ǵhu-tó-m, based on the root

- ǵhau-,

- ǵhau̯ǝ-, which meant "to call" or "to invoke". Alternatively, "Ghau" may be derived from a posthumously deified chieftain named "Gaut" — a name which sometimes appears for the Norse god Odin or one of his descendants. The Lombardic form of Odin, Godan, may derive from cognate Proto-Germanic *Ȝuđánaz.

The capitalized form "God" was first used in Ulfilas' Gothic translation of the New Testament, to represent the Greek Theos, and the Latin Deus (etymology "*Dyeus"). Because the development of English orthography was dominated by Christian texts, the capitalization (hence personalization and personal name) continues to represent a distinction between monotheistic "God" and the "gods" of pagan polytheism.

The name "God" now typically refers to the Abrahamic God of Judaism (El (god) YHVH), Christianity (God), and Islam (Allah). Though there are significant cultural divergences that are implied by these different names, "God" remains the common English translation for all. The name may signify any related or similar monotheistic deities, such as the early monotheism of Akhenaten and Zoroastrianism.

In the context of comparative religion, "God" is also often related to concepts of universal deity in Dharmic religions, in spite of the historical distinctions which separate monotheism from polytheism — a distinction which some, such as Max Müller and Joseph Campbell, have characterised as a bias within Western culture and theology.

Names of God

The noun God is the proper English name used for the deity of monotheistic faiths. Various English third-person pronouns are used for God, and the correctness of each is disputed. (See God and gender.)

Different names for God exist within different religious traditions:

- Abba is a name given to the Christian God. The name is used rarely and is Aramaic for "daddy", an allusion to "God the Father".[6]

- Allah is the Arabic name of God, which is used by Arab Muslims and also by most non-Muslim Arabs. ilah, cognate to northwest Semitic El (Hebrew "El" or more specifically "Eloha", Aramaic "Eloi"), is the generic word for a god (any deity), Allah contains the article, literally "The God". Also, when speaking in English, Muslims often translate "Allah" as "God". One Islamic tradition states that Allah has 99 names while others say that all good names belong to Allah. Similarly, in the Aramaic of Jesus, the word Alaha is used for the name of God.

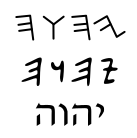

- Yahweh, Jehovah (Hebrew: 'Yud-Hay-Vav-Hay', יהוה ) are some of the names used for God in various translations of the Bible (all translating the same four letters - YHVH). El, and the plural/capital form Elohim, is another term used frequently, though El can also simply mean god in reference to deities of other religions. Others include El Shaddai, Adonai, Emmanuel. When Moses asked "What is your name?" he was given the answer Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh, which literally means, "I am that I am," as a parallel to the Tetragrammaton Yud-Hay-Vav-Hay. See The name of God in Judaism for Jewish names of God. Most Orthodox Jews, and many Jews of other denominations, believe it wrong to write the word "God" on any substance which can be destroyed. Therefore, they will write "G-d" or "Gd" as what they consider a more respectful symbolic representation. Others consider this unnecessary because English is not the "Holy Language" (i.e. Hebrew), but still will not speak the Hebrew representation written in the Torah, "Yud-Hay-Vav-Hay", aloud, and will instead use other names such as "Adonai" ("my Lord", used in prayer, blessings and other religious rituals) or the euphemism "Hashem" (literally "The Name", used at all other times). Another name especially used by ultra-Orthodox Jews is "HaKadosh Baruch Hu", meaning "The Holy One, Blessed is He".

- In early English Bibles, the Tetragrammaton was rendered in capitals: "IEHOUAH" in William Tyndale's version of 1525. The King James Version of 1611 renders YHWH as "The Lord", also as "Jehovah", see Psalms 83:18; Exodus 6:3.

- Research in comparative mythology shows a linguistic correlation between Levantine Yaw and monotheistic Yahweh, suggesting that the god may in some manner be the predecessor in the sense of an evolving religion of Yahweh.

- Elohim as "God" (with the plural suffix -im, but used with singular agreement); sometimes used to mean "gods" or apparently mortal judges.

- The Holy Trinity (one God in three Persons, the God the Father, the God the Son (Jesus Christ), and God the Holy Ghost/Holy Spirit) denotes God in almost all Christianity. Arab Christians will often also use "Allah" (the noun for "God" in Arabic) to refer to God.[citation needed]

- Deus, cognate of the Greek θέος (theos, '(male) deity') is the Latin word for God, and will be used in Latin portions of Roman Catholic masses. [1]

- God is called Igzi'abihier (lit. "Lord of the Universe") or Amlak (lit. the plural of mlk, "king" or "lord") in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

- Jah is the name of God in the Rastafari movement, referring specifically to Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia.

- The Maasai name for "God" is Ngai, (also spelled:'Ngai, En-kai, Enkai, Engai, Eng-ai) which occurs in the volcano name Ol Doinyo Lengai ("the mountain of God").

- The Mi'kmaq name for "God" is Niskam.

- Some churches (United Church of Canada, Religious Science) are using "the One" alongside "God" as a more gender-neutral way of referring to God (See also Oneness).

- Bhagavan - "The Opulent One", Brahman -"The Great", Paramatma - "The Supersoul" and Ishvara- "The Controller", are the terms used for God in the Vedas. A number of Hindu traditions worship a personal form of God or Ishvara, such as Vishnu or Shiva, whereas others worship a non-personal Supreme Cosmic Spirit, known as Brahman. The Vaishnava schools consider Vishnu or Krishna as the Supreme Personality of Godhead and within this tradition is the Vishnu sahasranama, which is a hymn describing the one thousand names of God (Vishnu). Shaivites consider Shiva as the Supreme God in similar way to the followers of Vaishnavism. The Supreme Ishvara of Hinduism must not be confused with the numerous deities or demigods which are collectively known as devas.

- Baquan is a phonetical pronunciation for God in several Pacific Islander religions.

- Buddhism is non-theistic (see God in Buddhism): instead of extolling an anthropomorphic creator God, Gautama Buddha employed negative theology to avoid speculation and keep the undefined as ineffable [citation needed]. Buddha believed the more important issue was to bring beings out of suffering to liberation. Enlightened ones are called Arhats or Buddha (e.g, the Buddha Sakyamuni), and are venerated. A bodhisattva is an altruistic being who has vowed to attain Buddhahood in order to help others to become Awakened ("Buddha") too. Buddhism also teaches of the existence of the devas or heavenly beings who temporarily dwell in celestial states of great happiness but are not yet free from the cycle of reincarnations (samsara). Some Mahayana and Tantra Buddhist scriptures do express ideas which are extremely close to pantheism, with a cosmic Buddha (Adibuddha) being viewed as the sustaining Ground of all being - although this is very much a minority vision within Buddhism.

- Jains invoke the five paramethis: Siddha, Arahant, Acharya, Upadhyaya, Sadhu. The arhantas include the 24 Tirthankaras from Lord Rishabha to Mahavira. But Jain philosophy as such does not recognize any Supreme Omnipotent creator God.

- Sikhs worship God with these common names Waheguru Wondrous God, Satnaam (True is Your Name), Akal (the Eternal) or Onkar (some similarity to the Hindu Aum). They believe that when reciting these names, devotion, dedication and a genuine appreciation and acceptance of the Almighty and the blessings thereof (as opposed to mechanical recitation) is essential if one is to gain anything by the meditation. The assistance of the guru is also believed to be essential to reach God.

- In Surat Shabda Yoga, names used for God include Anami Purush (nameless power) and Radha Swami (lord of the soul, symbolized as Radha).

- The Bahá'í Faith refers to God using the local word for God in whatever language is being spoken. In the Bahá'í Writings in Arabic, Allah is used. Bahá'ís share some naming traditions with Islam, but see "Bahá" (Glory or Splendour) as The Greatest Name of God. God's names are seen as attributes, and God is often, in prayers, referred to by these titles and attributes.

- The Shona people of Zimbabwe refer to God primarily as Mwari. They also use names such as Nyadenga in reference to his presumed residence in the 'heveans', or Musikavanhu, literally "the Creator".

- Zoroastrians worship Ahura Mazda.

- To many Native American religions, God is called "The Great Spirit", "The Master of Life", "The Master of Breath", or "Grandfather". For example, in the Algonquian first nations culture, Gitche Manitou or "Great Spirit" was the name adopted by French missionaries for the Christian God. Other similar names may also be used.

- Followers of Eckankar refer to God as SUGMAD or HU; the latter name is pronounced as a spiritual practice.

- In Chinese, the name Shang Ti 上帝 (Hanyu Pinyin: shàng dì) (literally King Above), is the name given for God in the Standard Mandarin Union Version of the Bible. Shen 神 (lit. spirit, or deity) was also adopted by Protestant missionaries in China to refer to the Christian God.

- Principle, Mind, Soul, Life, Truth, Love, and Spirit are names for God in Christian Science.[7] These names are considered synonymous and indicative of God's wholeness.

- Khoda is a word for God in Farsi.

Theological approaches

Theologians and philosophers have ascribed a number of attributes to God, including omniscience, omnipotence, omnipresence, perfect goodness, divine simplicity, and eternal and necessary existence. He has been described as incorporeal, a personal being, the source of all moral obligation, and the greatest conceivable existent.[1] These attributes were all supported to varying degrees by the early Jewish, Christian and Muslim scholars, including St Augustine,[3] Al-Ghazali,[4] and Maimonides.[3]

Many medieval philosophers developed arguments for the existence of God,[4] while attempting to comprehend the precise implications of God's attributes. Reconciling some of those attributes generated important philosophical problems and debates. For example, God's omniscience implies that God knows how free agents will choose to act. If God does know this, their apparent free will might be illusory, or foreknowledge does not imply predestination; and if God does not know it, God is not omniscient.[8]

The last few hundred years of philosophy have seen sustained attacks on the ontological, cosmological, and teleological arguments for God's existence. Against these, theists (or fideists) argue that faith is not a product of reason, but requires risk. There would be no risk, they say, if the arguments for God's existence were as solid as the laws of logic, a position famously summed up by Pascal as: "The heart has reasons which reason knows not of." [9]

Theologians attempt to explicate (and in some cases systematize) beliefs; some express their own experience of the divine. Theologians ask questions such as, "What is the nature of God?" "What does it mean for God to be singular?" "If people believe in God as a duality or trinity, what do these terms signify?" "Is God transcendent, immanent, or some mix of the two?" "What is the relationship between God and the universe, and God and humankind?"[citation needed]

Most major religions hold God not as a metaphor, but a being that influences our day-to-day existences. This is to say that people who have rejected the teachings of such religions typically view God as a metaphor or stand-in for the common aspirations and beliefs all humans share,[citation needed] rather than a sentient part of life; whereas organized religion tends to believe the opposite. Many believers allow for the existence of other, less powerful spiritual beings, and give them names such as angels, saints, djinni, demons, and devas.

Marxist writers see the idea of God as rooted in the powerlessness experienced by men and women in oppressive societies.[10][dubious – discuss] This however is an argument from motive.[dubious – discuss] Alister McGrath claims[11] that Marx is begging the question because he presupposes that God does not exist and then asks why would people believe in God and reaches a conclusion that the belief must stem from a defective mental motive, which is only true if in fact God does not exist and as such is circular in its reasoning.

See also:

- Relation of God to the Universe — Catholic Encyclopedia article

Theism and Deism

Theism holds that God exists realistically, objectively, and independently of human thought; that God created and sustains everything; that God is omnipotent and eternal, and is personal, interested and answers prayer. It holds that God is both transcendent and immanent; thus, God is simultaneously infinite and in some way present in the affairs of the world. Catholic theology holds that God is infinitely simple and is not involuntarily subject to time. Most theists hold that God is omnipotent, omniscient, and benevolent, although this belief raises questions about God's responsibility for evil and suffering in the world. Some theists ascribe to God a self-conscious or purposeful limiting of omnipotence, omniscience, or benevolence. Open Theism, by contrast, asserts that, due to the nature of time, God's omniscience does not mean the deity can predict the future. "Theism" is sometimes used to refer in general to any belief in a god or gods, i.e., monotheism or polytheism.

Deism holds that God is wholly transcendent: God exists, but does not intervene in the world beyond what was necessary to create it. In this view, God is not anthropomorphic, and does not literally answer prayers or cause miracles to occur. Common in Deism is a belief that God has no interest in humanity and may not even be aware of humanity. Pandeism and Panendeism, respectively, combine Deism with the Pantheistic or Panentheistic beliefs discussed below.

History of monotheism

Many historians of religion hold that monotheism may be of relatively recent historical origins — although comparison is difficult as many religions claim to be ancient. Native religions of China and India have concepts of panentheistic views of God that are difficult to classify along Western notions of monotheism vs. polytheism.

In the Ancient Orient, many cities had their own local god, although this henotheistic worship of a single god did not imply denial of the existence of other gods. The Hebrew Ark of the Covenant is supposed (by some scholars) to have adapted this practice to a nomadic lifestyle, paving their way for a singular God. Yet, many scholars now believe that it may have been the Zoroastrian religion of the Persian Empire that was the first monotheistic religion, and the Jews were influenced by such notions (this controversy is still being debated)[2].

The innovative cult of the Egyptian solar god Aten was promoted by the pharaoh Akhenaten (Amenophis IV), who ruled between 1358 and 1340 BC. The Aten cult is often cited as the earliest known example of monotheism, and is sometimes claimed to have been a formative influence on early Judaism, due to the presence of Hebrew slaves in Egypt. But even though Akhenaten's hymn to Aten offers strong evidence that Akhenaten considered Aten to be the sole, omnipotent creator, Akhenaten's program to enforce this monotheistic world-view ended with his death; the worship of other gods beside Aten never ceased outside his court, and the older polytheistic religions soon regained precedence.

Other early examples of monotheism include two late rigvedic hymns (10.129,130) to a Panentheistic creator god, Shri Rudram, a Vedic hymn to Rudra, an earlier aspect of Shiva often referred to by the ancient Brahmans as Stiva, a masculine fertility god, which expressed monistic theism, and is still chanted today; the Zoroastrian Ahuramazda and Chinese Shang Ti. The worship of polytheistic gods, on the other hand, is seen by many to predate monotheism, reaching back as far as the Paleolithic. Today, monotheistic religions are dominant in the many parts of the world, though other systems of belief continue to be prevalent.

Monotheism and pantheism

Monotheism holds that there is only one God, and/or that the one true God is worshiped in different religions under different names. The view that all religions are actually worshiping the same God, whether they know it or not, is especially emphasized in Hinduism.[12] Adherents of different religion, however, generally disagree as to how to best worship God and what is God's plan for mankind. There are different approaches to reconciling the contradictory claims of monotheistic religions. One view is taken by exclusivists, who believe they are the chosen people or have exclusive access to absolute truth, generally through revelation or encounter with the Divine, which adherents of other religions do not. Another view is religious pluralism. A pluralist typically believes that his religion is the right one, but but does not deny the partial truth of other religions. An example of a pluralist view in Christianity is supersessionism, i.e., the belief the one's religion is the fulfillment of previous religions. A third approach is relativistic inclusivism, where everybody is seen as equally right; an example in Christianity is universalism: the doctrine that salvation is eventually available for everyone. A fourth approach is syncretism, mixing different elements from different religion. An example of syncretism is the New Age movement.

Pantheism holds that God is the universe and the universe is God. Panentheism holds that God contains, but is not identical to, the Universe. The distinctions between the two are subtle, and some consider them unhelpful. It is also the view of the Liberal Catholic Church, Theosophy, Hinduism, some divisions of Buddhism, and Taoism, along with many varying denominations and individuals within denominations. Kabbalah, Jewish mysticism, paints a pantheistic/panentheistic view of God — which has wide acceptance in Hasidic Judaism, particularly from their founder The Baal Shem Tov — but only as an addition to the Jewish view of a personal god, not in the original pantheistic sense that denies or limits persona to God.

Speculative dilemmas

Dystheism is a form of theism which holds that God is malevolent as a consequence of the problem of evil. There is no known community of practicing dystheists. See also Satanism.

Nontheism holds that the universe can be explained without any reference to the supernatural, or to a supernatural being. Some non-theists avoid the concept of God, whilst accepting that it is significant to many; other non-theists understand God as a symbol of human values and aspirations. Many schools of Buddhism may be considered non-theistic.

Existence question

Many arguments for and against the existence of God have been proposed and rejected by philosophers, theologians, and other thinkers. In philosophical terminology, existence of God arguments concern schools of thought on the epistemology of the ontology of God.

There are many philosophical issues concerning the existence of God. Some definitions of God are so nonspecific that it is certain that something exists that meets the definition; while other definitions are apparently self-contradictory. Arguments for the existence of God typically include metaphysical, empirical, inductive, and subjective types. Arguments against the existence of God typically include empirical, deductive, and inductive types. Conclusions reached include: "God exists and this can be proven"; "God exists, but this cannot be proven or disproven" (theism in both cases); "God does not exist" (atheism); and "no one knows whether God exists" (agnosticism). There are numerous variations on these positions.

Scientific perspective

There is a lack of consensus as to the appropriate scientific treatment of religious questions, such as those of the existence and nature of God. A major point of debate has been whether God's existence or attributes can be empirically tested or gauged.

A common view divides the world into what Stephen Jay Gould called "non-overlapping magisteria" which is a concept often referred to by the acronym NOMA. In this view, questions of the supernatural, such as those relating to the existence and nature of God, are non-empirical and are the proper domain of theology. The methods of science should then be used to answer any empirical question about the natural world. The opposing view, advanced by Richard Dawkins, is that the existence of God is an empirical question, on the grounds that "a universe with a god would be a completely different kind of universe from one without, and it would be a scientific difference."[13] A third view is that of scientism: any question which cannot be answered by science is either nonsensical or is not worth asking, because there is no empirical answer.

Opinion statistics

As of 2005, approximately 54% of the world's population identifies with one of the three monotheistic Abrahamic religions. 15% identified as non-religious.[14] A 1995 survey showed similar numbers for the non-religious, though on the specific question of belief in God, only 3.8% identified as atheist.[15]

Popular culture

God, as a humanized figure, usually taking the form of a man, has often appeared as a character in various works of fiction such as movies, books, and television shows. Though depictions vary, he is usually portrayed as sage, wise, and old, with a patient and calm personality. In cartoons God is usually depicted as a caricature of Michelangelo's classic painting.

See also:

- Depictions of God in popular culture

- List of appearances of God in fiction

- Parodies of God and religion

See also

See alsoGeneral approaches

Various issues |

Specific conceptions

General practices |

Notes

- ^ a b c Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 1995. "Most philosophical theologians have tried to say something about what God is like. In so doing, they have generally regarded him as a personal being, bodiless, omnipresent, creator and sustainer of any universe there may be, perfectly free, omnipotent, omniscient, perfectly good, and a source of moral obligation; who exists eternally and necessarily, and has essentially the divine properties which I have listed. Many philosophers (influenced by Anselm) have seen these properties as deriving from the property of being the greatest conceivable being."

- ^ "Religions by Adherents". adherents.com. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ^ a b c d Edwards, Paul. "God and the philosophers" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ^ a b c d Plantinga, Alvin. "God, Arguments for the Existence of," Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Routledge, 2000.

- ^ Beaty, Michael (1991). "God Among the Philosophers". The Christian Century. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ^ Tarazi, Paul. "The Name of God: Abba". Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ^ M-w.com. See definitions of Principle, Mind, Soul, Life, Truth, Love, and Spirit.

- ^ Wierenga, Edward R. "Divine foreknowledge" in Audi, Robert. The Cambridge Companion to Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- ^ Pascal, Blaise. Pensées, 1669.

- ^ Wolff, Jonathan (2003-08-26). "Karl Marx". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, CSLI, Stanford University. Retrieved 2006-10-31.

- ^ McGrath 2004, p. 180

- ^ See Swami Bhaskarananda, Essentials of Hinduism (Viveka Press 2002) ISBN 1884852041

- ^ Dawkins, Richard. "Why There Almost Certainly Is No God". Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ See Major religious groups.

- ^ See Demographics of atheism

References

- BBC, Nigeria leads in religious belief

- Pickover, Cliff, The Paradox of God and the Science of Omniscience, Palgrave/St Martin's Press, 2001. ISBN 1-4039-6457-2

- Collins, Francis, The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief, Free Press, 2006. ISBN 0743286391

- Harris interactive, While Most Americans Believe in God, Only 36% Attend a Religious Service Once a Month or More Often

- Miles, Jack, God: A Biography, Knopf, 1995, ISBN 0-679-74368-5 Book description.

- Armstrong, Karen, A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, Ballantine Books, 1994. ISBN 0-434-02456-2

- McGrath, Alister, The Twilight of Atheism, Doubleday, 2004. ISBN 0-385-50061-0

- Pew research center, The 2004 Political Landscape Evenly Divided and Increasingly Polarized - Part 8: Religion in American Life

- Sharp, Michael, The Book of Light: The Nature of God, the Structure of Consciousness, and the Universe Within You. Avatar Publications, 2005. ISBN 0-9738555-2-5. free as eBook

- Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology, Vol. 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951). ISBN 0-226-80337-6

External links

- God - a Christian perspective

- "Nature of God" at Mormon.org

- What Is God at Wikireason.net

- The Creation Of God at Wikireason.net

- God in Judaism on chabad.org Retrieved 2006-10-05

- Cheung, Vincent (2003). "Systematic Theology"

- Islam-info.ch (2006) Concept of God in Islam.

- Draye, Hani (2004). Concept of God in Islam. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- Haisch, Bernard (2006). The God Theory: Universes, Zero-Point Fields and What's Behind It All.

- Jewish Literacy. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- Nicholls, David (2004). DOES GOD EXIST?. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- Salgia, Amar (1997) Creator-God and Jainism Retrieved 2005-10-18.

- Shaivam.org (2004). Hindu Concept of God. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- Who Is God? from the Yoga point of view.

- Schlecht, Joel (2004). The God Particle. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2004). Moral Arguments for the Existence of God. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2005). God and Other Necessary Beings. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- Students of Shari'ah (2005). Proof Of Creator. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- Monotheistic gods and Dualism

- The Cathar understanding of God. A Gnostic belief system

- The Old Path. Almighty God: Proof of his Existence according to the Bible

- The Old Path. How Great is God of the Bible

- Rays Of God Photography Rays Of God

[[3]]