Santa Susana Field Laboratory

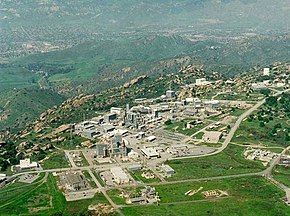

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL), formerly known as Rocketdyne, is a complex of industrial research and development facilities located on a 2,668-acre (1,080 ha)[1] portion of Southern California in an unincorporated area of Ventura County in the Simi Hills between Simi Valley and Los Angeles. The site is located approximately 18 miles (29 km) northwest of Hollywood and approximately 30 miles (48 km) northwest of Downtown Los Angeles. Sage Ranch Park is adjacent on part of the northern boundary and the community of Bell Canyon is along the entire southern boundary.[2]

SSFL was used mainly for the development and testing of liquid-propellant rocket engines for the United States space program from 1949 to 2006,[1] nuclear reactors from 1953 to 1980 and the operation of a U.S. government-sponsored liquid metals research center from 1966 to 1998.[3] Throughout the years, about ten low-power nuclear reactors operated at SSFL, (including the Sodium Reactor Experiment, the first reactor in the United States to generate electrical power for a commercial grid, and the first commercial power plant in the world to experience a partial core meltdown) in addition to several "critical facilities" that helped develop nuclear science and applications. At least four of the ten nuclear reactors had accidents during their operation. The reactors located on the grounds of SSFL were considered experimental, and therefore had no containment structures.

The site ceased research and development operations in 2006. The years of rocket testing, nuclear reactor testing, and liquid metal research have left the site "significantly contaminated". Environmental cleanup is ongoing. The public who live near the site have strongly urged a thorough cleanup of the site, citing cases of long term illnesses, including cancer cases at rates they claim are higher than normal. On 30 March 2018, a 7-year-old girl living in Simi Valley died of neuroblastoma, prompting public urging to thoroughly clean up the site. Experts have said, however, that there is insufficient evidence to identify an explicit link between cancer rates and radioactive contamination in the area.[4]

Introduction

Since 1947 the Santa Susana Field Laboratory location has been used by a number of companies and agencies. The first was Rocketdyne, originally a division of North American Aviation (NAA), which developed a variety of pioneering, successful, and reliable liquid rocket engines.[5] Some were used in the Navaho cruise missile, the Redstone rocket, the Thor and Jupiter ballistic missiles, early versions of the Delta and Atlas rockets, the Saturn rocket family, and the Space Shuttle Main Engine.[6] The Atomics International division of North American Aviation used a separate and dedicated portion of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory to build and operate the first commercial nuclear power plant in the United States,[7] as well as for the testing and development of compact nuclear reactors, including the first and only known nuclear reactor launched into Low Earth Orbit by the United States, the SNAP-10A.[8] Atomics International also operated the Energy Technology Engineering Center for the U.S. Department of Energy at the site. The Santa Susana Field Laboratory includes sites identified as historic by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics and by the American Nuclear Society. In 1996, The Boeing Company became the primary owner and operator of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory and later closed the site.

Three California state agencies and three federal agencies have been overseeing a detailed investigation of environmental impacts from historical site operations since at least 1990.[9] Concerns about the environmental impact of past disposal practices have inspired at least two lawsuits seeking payment from Boeing, and several interest groups are actively involved with steering the ongoing environmental investigation.

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory is the focus of diverse interests. Burro Flats Painted Cave, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is located within the Santa Susana Field Laboratory boundaries, on a portion of the site owned by the U.S. government.[10] The drawings within the cave have been termed "the best preserved Indian pictograph in Southern California." Several tributary streams to the Los Angeles River have headwater watersheds on the SSFL property, including Bell Creek (90% of SSFL drainage), Dayton Creek, Woolsey Canyon, and Runkle Creek.[11]

History

SSFL was a United States government facility dedicated to the development and testing of nuclear reactors, powerful rockets such as the Delta II, and the systems that powered the Apollo missions. The location of SSFL was chosen in 1947 for its remoteness in order to conduct work that was considered too dangerous and too noisy to be performed in more densely populated areas. In subsequent years, however, the Southern California population grew, along with housing developments surrounding "The Hill".

The site is divided into four production and two buffer areas (Area I, II, III, and IV, and the northern and southern buffer zones). Areas I through III were used for rocket testing, missile testing, and munitions development. Area IV was used primarily for nuclear reactor experimentation and development. Laser research for the Strategic Defense Initiative (popularly known as "Star Wars") was also conducted in Area IV.[12]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2010) |

Rocket engine development

North American Aviation (NAA) began its development of liquid propellant rocket engines after the end of WWII. The Rocketdyne division of NAA, which came into being under its own name in the mid-1950s,[citation needed] designed and tested several rocket engines at the facility. They included engines for the Army's Redstone (an advanced short-range version of the German V-2), and the Army Jupiter intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM) as well as the Air Force's counterpart IRBM, the Thor.[citation needed] Also included among those developed there, were engines for the Atlas Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), as well as the twin combustion chamber alcohol/liquid oxygen booster engine for the Navaho, a large, intercontinental cruise missile that never became operational. Later, Rocketdyne designed and tested the J-2 liquid oxygen/hydrogen engine which was used on the second and third stages of the Saturn V launch rocket developed for the moon-bound Project Apollo mission. While the J-2 was tested at the facility, Rocketdyne's huge F-1 engine for the first stage of the Saturn V was tested in the Mojave desert near Edwards Air Force Base. This was due to safety and noise considerations, since SSFL was too close to populated areas.[13]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2010) |

Nuclear and energy research and development

The Atomics International Division of North American Aviation used SSFL Area IV as the site of United States first commercial nuclear power plant [14] and the testing and development of the SNAP-10A, the first nuclear reactor launched into outer space by the United States.[15] Atomics International also operated the Energy Technology Engineering Center at the site for the U.S. government. As overall interest in nuclear power declined, Atomics International made a transition to non-nuclear energy-related projects, such as coal gasification, and gradually, ceased designing and testing nuclear reactors. Atomics International eventually was merged with the Rocketdyne division in 1978.[16]

Sodium reactor experiment

The Sodium Reactor Experiment (SRE) was an experimental nuclear reactor that operated at the site from 1957 to 1964 and was the first commercial power plant in the world to experience a core meltdown.[17] There was a decades-long cover-up of the incident by the U.S. Department of Energy.[18] The operation predated environmental regulation, so early disposal techniques are not recorded in detail.[18] Thousands of pounds of sodium coolant from the time of the meltdown are not yet accounted for.[19][20]

The reactor and support systems were removed in 1981 and the building torn down in 1999.

The 1959 sodium reactor incident was chronicled on History Channel's program Engineering Disasters 19.

Energy Technology Engineering Center

The Energy Technology Engineering Center (ETEC), was a government-owned, contractor-operated complex of industrial facilities located within Area IV of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory. The ETEC specialized in non-nuclear testing of components which were designed to transfer heat from a nuclear reactor using liquid metals instead of water or gas. The center operated from 1966 to 1998.[21] The ETEC site has been closed and is now[needs update] undergoing building removal and environmental remediation by the U.S. Department of Energy.[citation needed]

Accidents and site contamination

Nuclear reactors

Throughout the years, approximately ten low-power nuclear reactors operated at SSFL, in addition to several "critical facilities": a sodium burn pit in which sodium-coated objects were burned in an open pit; a plutonium fuel fabrication facility; a uranium carbide fuel fabrication facility; and the purportedly largest "Hot Lab" facility in the United States at the time.[22] (A hot lab is a facility used for remotely handling or machining radioactive material.) Irradiated nuclear fuel from other Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and Department of Energy (DOE) facilities from around the country was shipped to SSFL to be decladded and examined.

The hot lab suffered a number of fires involving radioactive materials. For example, in 1957, a fire in the hot cell "got out of control and ... massive contamination" resulted.[23]

At least four of the ten nuclear reactors suffered accidents: 1) The AE6 reactor experienced a release of fission gases in March 1959.[24] 2) In July 1959, the SRE experienced a power excursion and partial meltdown that released 28 Curies of radioactive noble gases. The release resulted in the maximum off-site exposure of 0.099 millirem and an exposure of 0.018 millirem for the nearest residential building which is well within current limits today.[25] 3) In 1964, the SNAP8ER experienced damage to 80% of its fuel. 4) In 1969 the SNAP8DR experienced similar damage to one-third of its fuel.[24]

A radioactive fire occurred in 1971, involving combustible primary reactor coolant (NaK) contaminated with mixed fission products.[26][27]

Sodium burn pits

The sodium burn pit, an open-air pit for cleaning sodium-contaminated components, was also contaminated[when?] by the burning of radioactively and chemically contaminated items in it, in contravention of safety requirements. In an article in the Ventura County Star, James Palmer, a former SSFL worker, was interviewed. The article notes that "of the 27 men on Palmer's crew, 22 died of cancers." On some nights Palmer returned home from work and kissed "his wife [hello], only to burn her lips with the chemicals he had breathed at work." The report also noted that "During their breaks, Palmer's crew would fish in one of three ponds ... The men would use a solution that was 90 percent hydrogen peroxide to neutralize the contamination. Sometimes, the water was so polluted it bubbled. The fish died off." Palmer's interview ended with: "They had seven wells up there, water wells, and every damn one of them was contaminated," Palmer said, "It was a horror story."[28]

In 2002, a Department of Energy (DOE) official described typical waste disposal procedures used by Field Lab employees in the past. Workers would dispose of barrels filled with radioactive sodium by dumping them in a pond and then shooting the barrels with rifles so that they would explode and release their contents into the air.[29] Since then, the pit has been remediated by having 22,000 cubic yards of soil removed down 10-12 feet to bedrock.[29]

On 26 July 1994, two scientists, Otto K. Heiney and Larry A. Pugh were killed when the chemicals they were illegally burning in open pits exploded. After a grand jury investigation and FBI raid on the facility, three Rocketdyne officials pleaded guilty in June 2004 to illegally storing explosive materials. The jury deadlocked on the more serious charges related to illegal burning of hazardous waste.[30][31] At trial, a retired Rocketdyne mechanic testified as to what he witnessed at the time of the explosion: "I assumed we were burning waste," Lee Wells testified, comparing the process used on 21 and 26 July 1994, to that once used to legally dispose of leftover chemicals at the company's old burn pit. As Heiney poured the chemicals for what would have been the third burn of the day, the blast occurred, Wells said. "[The background noise] was so loud I didn't hear anything ... I felt the blast and I looked down and my shirt was coming apart." When he realized what had occurred, Wells said, "I felt to see if I was all there ... I knew I was burned but I didn't know how bad." Wells suffered second- and third-degree burns to his face, arms and stomach.[32]

2018 Woolsey fire

The 2018 Woolsey Fire began at SSFL and burned about 80% of the site.[33] After the fire, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health found "no discernible level of radiation in the tested area" and the California Department of Toxic Substances Control, which is overseeing cleanup of the site, said in an interim report that "previously handled radioactive and hazardous materials were not affected by the fire."[34] Bob Dodge, President of Physicians for Social Responsibility-Los Angeles, said "When it burns and becomes airborne in smoke and ash, there is real possibility of heightened exposure for area residents."[34]

In 2020, the California Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) stated in their final report that the fire did not cause contaminants to be released from the site into Simi Valley and other neighboring communities and that the risk from smoke exposure during the fire was not higher than what is normally associated with wildfire.[35][36]

In 2021 a study which collected 360 samples of dust, ash, and soils from homes and public lands three weeks after the fire found that most samples were at normal levels, ("Data did not support a finding of widespread deposition of radioactive particles.") but that two locations "contained high activities of radioactive isotopes associated with the Santa Susana Field Laboratory."[33][37]

Medical claims

In October 2006, the Santa Susana Field Laboratory Advisory Panel, made up of independent scientists and researchers from around the United States, concluded that based on available data and computer models, contamination at the facility resulted in an estimated 260 cancer related deaths. The report also concluded that the SRE meltdown caused the release of more than 458 times the amount of radioactivity released by the Three Mile Island accident. While the nuclear core of the SRE released 10 times less radiation than the TMI incident, the lack of proper containment such as concrete structures caused this radiation to be released into the surrounding environment. The radiation released by the core of the TMI was largely contained.[38]

According to studies conducted by Hal Morgenstern between 1988 and 2002, residents living within 2 miles of the laboratory are 60% more likely to be diagnosed with certain cancers compared to residents living 5 miles from the laboratory, though Morgenstern said that the lab is not necessarily the cause.[4]

Cleanup

During its years of operation, highly toxic chemical additives were widely used in order to power over 30,000 rocket engine tests and to clean the rocket test-stands afterwards. In addition, considerable nuclear research and at least four nuclear accidents occurred, which resulted in the SSFL becoming a seriously contaminated site and an offsite pollution source, requiring a sophisticated multi-agency Cleanup Project.[39] An ongoing process to determine the site contamination levels and locations, cleanup standards to meet, methods to use, costs, timelines and completion requirements – are still being debated, and litigated.[40]

Standards history

In early May 2007, a Federal Court in San Francisco issued a major ruling which concluded that DOE has not been cleaning up the site to proper standards, and that the site would have to be cleaned up to higher standards if DOE ever wanted to release the site to Boeing, which in turn, would most likely release the land for unrestricted residential development.[41] Judge "Conti's ruling requires DOE to prepare a more stringent review of the lab, which is on the border of Los Angeles County. Conti wrote that the department's decision to prepare a less-stringent environmental document prior to cleanup is in violation of the National Environmental Policy Act and noted that the lab 'is located only miles away from one of the largest population centers in the world.'"

Runoff issues

On 26 July 2007, the staff at the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board recommended a $471,190 fine against Boeing for 79 violations of the California Water Code during an 18-month period. From October 2004 to January 2006, wastewater and stormwater runoff coming from the lab had increased levels of chromium, dioxin, lead, mercury, and other pollutants, the board said. The contaminated water flowed into Bell Creek and the Los Angeles River in violation of a 1 July 2004 permit that allowed the release of wastewater and stormwater runoff as long as it didn't contain high levels of pollutants.[42]

Parkland

In October 2007, Boeing announced that "In a landmark agreement between Boeing and California officials, nearly 2,400 acres (10 km2) of land that is currently Boeing's Santa Susana Field Laboratory will become state parkland. According to the plan jointly announced by California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, Boeing, and state Sen. Sheila Kuehl, the property will be donated and preserved as a vital undeveloped open-space link in the Simi Hills, above the Simi Valley and the San Fernando Valley. The agreement will permanently restrict the land for nonresidential, noncommercial use."[43][44]

Cleanup developments 2007–present

SB 990

The California state senate bill SB 990, passed into law in 2007, set the standards for the site's cleanup.[45] To achieve them, the responsible parties, consisting of Boeing, DOE, and NASA, need to sign agreements of acceptance and cleanup compliance.[original research?]

Boeing

Boeing contested the law, filing a lawsuit in September 2009 to release it from compliance, with a court date set for summer 2011. Boeing won the suit and claims it will clean up the site, although to levels far below those outlined in SB 990.[46]

DOE and NASA

In September 2010 DOE and NASA agreed to meet the stringent cleanup standards set for the site in the state's SB 990 legislation, and to cover all costs for their cleanup's implementation. This agreement marks significant progress in the SSFL cleanup sequence.[47] In 2014, NASA issued a final environmental impact statement containing mitigation measures that would demolish all structures and remediate soil and groundwater contamination.[48] NASA issued a 2014 report highlighting cleanup technology feasibility studies, soil and groundwater fieldwork, and additional archaeology surveys that would be performed in preparation for the demolition of the structures.[49] NASA determined that substantially more soil needed to be removed from its part of the site than what it estimated in the 2014 report so a supplemental report was prepared in 2019.[50]

Demolition of abandoned buildings on the site was scheduled to start in early 2015 after abatement of asbestos, lead paint and other regulated materials. The test stands would follow and are the most complex to tear down but all demolition was to have been completed in 2016. Because of their historical significance, one test stand and one control building will remain if the cleanup goals can still be met.[51] The cleanup was projected to be completed in 2017.[47] In 2019, the U.S. Department of Energy announced that it has decided to demolish and remove 13 of 18 remaining structures.[52] In 2020, an agreement was reached to demolish 10 of the most highly contaminated structures.[53]

Parts of this article (those related to inline) need to be updated. (September 2019) |

Community involvement

Community advisory group

A petition to form a "CAG" or community advisory group was denied in March 2010 by DTSC.[54][55] In 2012, the current CAG's petition was approved. The SSFL CAG recommends that all responsible parties execute a risk-based cleanup to EPA's suburban residential standard that will minimize excavation, soil removal and backfill and thus reduce danger to public health and functions of surrounding communities. However, SSFL Panel believes the CAG has a conflict of interest, as it is funded in large part by a grant from the U.S. Department of Energy, and three of its members are former employees of Boeing or its parent company, North American Aviation.[56]

Documentary

In 2021, the three hour documentary In the Dark of the Valley depicted mothers advocating for cleanup of the site who have children suffering from cancer believed to be caused by the contamination.[57]

See also

- Nuclear and radiation accidents and incidents

- Nuclear labor issues

- Nuclear reactor accidents in the United States

References

- ^ a b Archeological Consultants, Inc.; Weitz Research (March 2009). "Historical resources survey and assessment of the NASA facility at the Santa Susana Field Laboratory, Simi Valley, California" (PDF). NASA. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ "Sage.Park".

- ^ Sapere and Boeing (May 2005). Santa Susana Field Laboratory, Area IV Historical Site Assessment. p. 2. Archived from the original on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ a b Simon, Melissa (13 April 2018). "Protestors want SSFL cleaned up | Simi Valley Acorn". www.simivalleyacorn.com. Simi Valley Acorn. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

But there is no definitive proof that the contamination left from decades of nuclear testing is the source of cancers and other health issues. ... Hal Morgenstern, an epidemiology professor at the University of Michigan, conducted several studies between 1988 and 2002 to see if there was a link between chemical or radioactive contamination at the field lab and deaths caused by leukemia, lymphoma and other cancers. Results showed people living within a 2-mile radius were at least 60 percent more likely to be diagnosed with certain cancers than those living 5 miles away, but that doesn't mean the site's contamination is the cause, Morgenstern previously told the Simi Valley Acorn. Despite the data he collected, Morgenstern said, there wasn't enough evidence to identify an explicit link between cancer and field lab contamination. And the results were inconclusive as to whether activities at SSFL specifically affected or will affect cancer incidences, he said.

- ^ "Boeing: Environment - Santa Susana - History". Archived from the original on 26 February 2011.

- ^ American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (2001). "Historic Aerospace Site: The Rocketdyne Santa Susana Field Laboratory, Canoga Park, California" (PDF). AIAA. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ DuTemple, Octave. "American Nuclear Society Sodium Reactor Experiment Nuclear Historic Landmark awarded, February 21, 1986" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ Stokely, C. & Stansbury, E. (2008), "Identification of a debris cloud from the nuclear powered SNAPSHOT satellite with Haystack radar measurements", Advances in Space Research, vol. 41, no. 7, pp. 1004–1009, Bibcode:2008AdSpR..41.1004S, doi:10.1016/j.asr.2007.03.046, hdl:2060/20060028182

- ^ Santa Susana Field Laboratory Workgroup (20 September 1990). "Santa Susana Field Laboratory Workgroup Charter" (PDF). Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ Chiotakis, Steve (15 October 2020). "Cancer, contamination, and cave paintings: Santa Susana cleanup gets more complicated". KCRW. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "SSFL Surface Water Map".

- ^ "Site Safety and Health Plan Area IV Radiological Study Santa Susana Field Laboratory Ventura County, California" (PDF). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ "Apollo Expeditions to the Moon, Chapter 3.2". NASA.

- ^ U.S. Energy Information Agency. "California Nuclear Industry". Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ Voss, Susan (August 1984). SNAP Reactor Overview. U.S. Air Force Weapons Laboratory, Kirtland AFB, New Mexico. p. 57. AFWL-TN-84-14.

- ^ Sapere and Boeing (May 2005). Santa Susana Field Laboratory Area IV, Historical Site Assessment. pp. 2–1. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ Trossman Bien, Joan; Collins, Michael (24 August 2009). "50 Years After America's Worst Nuclear Meltdown: Human error helped worsen a nuclear meltdown just outside Los Angeles, and now human inertia has stymied the radioactive cleanup for half a century". Pacific Standard. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b "{Pack, 1964 #4592} has map of complex trajectories in Los Angeles basin" (PDF). Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Rockwell International Corporation, Energy Systems Group. "Sodium Reactor Experiment Decommissioning Final Report" (PDF). ESG-DOE-13403. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2011. (see sections 2.1.7.4, 2.2.3, 4.4.2 and 9.3 for discrepancies concerning sodium amounts)

- ^ Grover, Joel; Glasser, Matthew. "L.A.'s Nuclear Secret". NBC. National Broadcasting Company. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ Sapere and Boeing (May 2005). Santa Susana Field Laboratory, Area IV, Historical Site Assessment. pp. 2–1. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ Grover, Joel; Glasser, Matthew. "L.A.'s Nuclear Secret". I-Team: 7-part NBC News special report. NBC News. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ NAA-SR-1941, Sodium Graphite Reactor, Quarterly Progress Report, January–March 1957, p. 27

- ^ a b "Report of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory Advisory Panel" (PDF). October 2006. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ^ "Accident report" (PDF). www.etec.energy.gov.

- ^ Rockwell International, Nuclear Operations at Rockwell's Santa Susana Field Laboratory – A Factual Perspective, 6 September 1991

- ^ "Oak Ridge Associated Universities TEAM Dose Reconstruction Project for NIOSH, Document No. ORAUT-TKBS-0038-2, Rev. 0" (PDF). p. 24. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ^ ”The Cancer Effect”, 30 October 2006, Ventura County Star

- ^ a b Collins, Michael (19 February 2003). "Rocketdyne: It's the pits - Lots of questions, few answers at the latest meeting on Rocketdyne cleanup". Ventura County Reporter. Archived from the original on 19 February 2003.

Lopez described the cleanup of the heavily polluted sodium burn pit, a six-acre site where Rocketdyne disposed of massive amounts of radioactive waste. The modus operandi included chucking barrels of radioactive sodium into the sludgy pond and firing a gun at the canisters, which would then explode, releasing radioactive contaminants into the air. Lopez said that the pit has now been excavated ten to 12 feet down to the bedrock, resulting in the removal of 22,000 cubic yards of soil.

- ^ Guccione, Jean (11 December 2003). "Scientist Fined $100 in Lab Blast That Killed 2". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Guccione, Jean (28 January 2003). "Executive Sentenced in '94 Blast". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Guccione, Jean (5 January 2002). "Ex-Rocketdyne Worker Describes Fatal 1994 Blast". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b Harris, Mike (17 October 2021). "Study finds radioactive contamination migrated off field lab site during Woolsey Fire". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

The Woolsey Fire broke out at the site on Nov. 8, 2018, sparked during high winds by electrical equipment owned there by Southern California Edison, an investigation by the Ventura County Fire Department concluded. The blaze went on to burn about 97,000 acres, including 80% of the field lab site, ... The study examined 360 samples of household dust, surface soils and ash from 150 homes and other locations such as parks and trails collected after the fire. It concluded that while most of the collected samples were at normal levels, "some ashes and dusts collected from the Woolsey Fire zone in the fire's immediate aftermath contained high activities of radioactive isotopes associated with the Santa Susana Field Laboratory."

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Ortiz, Erik (14 November 2018). "Activists concerned after wildfire ripped through nuclear research site". NBC News. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ "DTSC Final Summary Report of Woolsey Fire" (PDF). California Department of Toxic Substances Control. 1 December 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Harris, Mike (19 January 2021). "State reaffirms Woolsey Fire didn't cause toxins to be released from field lab site". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Kaltofen, Marco; Gundersen, Maggie; Gundersen, Arnie (1 December 2021). "Radioactive microparticles related to the Woolsey Fire in Simi Valley, CA". Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 240: 106755. doi:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2021.106755. PMID 34634531. S2CID 238637473.

In two geographically-separated locations, one as far away as 15 km, radioactive microparticles containing percent-concentrations of thorium were detected in ashes and dusts that were likely related to deposition from the Woolsey fire. These offsite radioactive microparticles were colocated with alpha and beta activity maxima. Data did not support a finding of widespread deposition of radioactive particles. However, two radioactive deposition hotspots and significant offsite contamination were detected near the site perimeter.

- ^ "Panel Report" (PDF). www.ssflpanel.org.

- ^ "Boeing: Santa Susana Field Laboratory". www.boeing.com.

- ^ Hiltzik, Michael (13 June 2014). "Santa Susana toxic cleanup effort is a mess". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ Griggs, Gregory W. (3 May 2007). "Judge assails Rocketdyne cleanup". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ Griggs, Gregory W. (27 July 2007). "Boeing faces fines over field lab runoff". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ "Santa Susana". Boeing. A Bright Future, Today. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Roth, Annie (21 June 2018). "Den of Mountain Lion Kittens Found in Unlikely Place". National Geographic. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Bill Text - SB-990 Hazardous waste: Santa Susana Field Laboratory". leginfo.legislature.ca.gov.

- ^ Healy, Patrick and Lloyd, Jonathan (29 April 2011) "Judge Sides With Boeing in Rocket Site Cleanup" NBC Southern California

- ^ a b Sahagun, Louis (4 September 2010). "Nuclear cleanup at Santa Susana facility would finish by 2017 under settlement". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ Harris, Mike (14 March 2014). "NASA's Santa Susana cleanup could have significant impacts, report says". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ Sullivan, Bartholomew (1 May 2014). "NASA plans to raze structures at Santa Susana Field Laboratory". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ Harris, Mike (22 November 2019). "Fireworks at NASA meeting for cleaning up nuke meltdown at Santa Susana Field Lab". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ Harris, Mike (6 December 2014). "Historic NASA structures to be razed in Santa Susana cleanup". Ventura County Star.

- ^ Harris, Mike (25 September 2019). "Feds move to demolish 13 structures at toxic Santa Susana site without state oversight". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ Puko, Timothy (20 May 2020). "U.S., California Strike Deal to Clean Up Nuclear Site Near L.A." Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ http://cleanuprocketdyne.org/cleanuprocketdyne.org/Community_Advisory_Group/Community_Advisory_Group.html. accessed 30 August 2010[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Petition Final Response" (PDF). California Department of Toxic Substances Control. 19 March 2010.

- ^ "Dept. of Energy secretly funding front group to sabotage its own Santa Susana Field Lab cleanup". 1 September 2016.

- ^ Mihm, Nicholas (director) (14 November 2021). In the Dark of the Valley (Motion picture). Los Angeles, CA.

External links and sources

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Agencies

- CA-DTSC-Santa Susana Field Laboratory website: site investigation and cleanup news, Listserv e-mail newsletter, calendar, documentation download links, contacts.

- "U.S. DOE ETEC Closure Project Website". DOE-sponsored project website provides historical ETEC technology development, site usage and current closure project information. Interactive graphic found in Regulation section explains the various involved regulatory agencies and their roles at the site. Large number of documents located in the Reading Room. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- "DTSC-Santa Susana Field Laboratory Site Investigation and Cleanup website". Hosted by the California State Department of Toxic Substances Control which oversees the investigation and cleanup of chemicals in the soil and groundwater at the SSFL. Project status documents, reports and public comment materials are available. Retrieved 14 September 2006.

- "SSFL Ground Water Contamination: Preliminary Analysis" (PDF). Retrieved 30 September 2005. – PDF of a presentation given on 19 August 2003.

- "Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL)". The Decontamination and Decommissioning Science Consortium. Retrieved 30 September 2005.

- "Discussed at FARK: Radioactive emissions from a nuclear meltdown in California 47 years ago are worse than anybody thought. In other news, there was a nuclear meltdown in the US back in 1959". Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- The Santa Susana Advisory Panel

- The Rocketdyne Information Society Public Forum on SSFL cleanup.

- History Channel – "Rocketdyne Meltdown" on YouTube

- lamountains Sage Ranch Park website.

- "Boeing: About Us – Santa Susana website". Brief website hosted by The Boeing Company, the largest landowner of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory. This site contains general information and a cleanup completion schedule for the soil and groundwater projects. Surface water discharge-related information for SSFL is posted in the Environmental Programs section. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- "Santa Susana Field Laboratory". U.S. DOE Office of Environmental Management. Retrieved 30 September 2005.

- "Draft Preliminary Site Evaluation of Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL)". U.S. DOE ATSDR – Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

Groups and info

- Sage Ranch Park website

- "Environment Site Restoration Summary – Santa Susana Field Laboratory". U.S. DOE Office of Environmental Management. Retrieved 30 September 2005.

- "Energy Technology Engineering Center, Santa Susana Field Lab". Center for Land Use Interpretation. Retrieved 30 September 2005.

- "SSFL Ground Water Contamination: Preliminary Analysis" (PDF). Retrieved 30 September 2005. – PDF of a presentation given on 19 August 2003.

- "Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL)". The Decontamination and Decommissioning Science Consortium. Retrieved 30 September 2005.

Media

- EnviroReporter.com: Investigative news website that has coverage of Rocketdyne issues since 1998, often in partnership with regional publications including the LA Weekly and Ventura County Reporter newspapers.

- History Channel History Channel: "Rocketdyne Meltdown" on YouTube

- "The Rockets' Red Glare: First Installment". An upcoming documentary film recounts the horrors and hazards of the work done at Boeing's Santa Susana Field Laboratory. This first installment focuses on the workers and their every-day exposure to the hazardous environment provided by the owners and operators of this lab. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- "Discussed at FARK: Radioactive emissions from a nuclear meltdown in California 47 years ago are worse than anybody thought. In other news, there was a nuclear meltdown in the US back in 1959". Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- Joel Grover and Matthew Glasser LA'S Nuclear Secret, Part 1-5 NBC4, 21 September 2015, retrieved 23 December 2015.

Reactor accident sources

- "-NAA-SR-MEMO-3757" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2007., Release of Fission Gas from the AE-6 Reactor, hosted by RocketdyneWatch.org

- "-NAA-SR-5898" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2007., Analysis of SRE Power Excursion, hosted by RocketdyneWatch.org

- "-NAA-SR-4488" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2007., SRE Fuel Element Damage an Interim Report, hosted by RocketdyneWatch.org

- "-NAA-SR-4488-Suppl" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2007., SRE Fuel Element Damage Final Report, hosted by RocketdyneWatch.org

- "-NAA-SR-MEMO-12210" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2007., SNAP8 Experimental Reactor Fuel Element Behavior: Atomics International Task Force Review, hosted by RocketdyneWatch.org

- "-NAA-SR-12029" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2007., Postoperation Evaluation of Fuel Elements from the SNAP8 Experimental Reactor hosted by RocketdyneWatch.org

- "-AI-AEC-13003" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2007., Findings of the SNAP 8 Developmental Reactor (S8DR) Post-Test Examination, hosted by RocketdyneWatch.org

- Rocketdyne

- Rocketry

- Energy infrastructure in California

- Nuclear research institutes

- Simi Hills

- Atomics International

- North American Aviation

- Boeing

- Buildings and structures in Ventura County, California

- Buildings and structures in Los Angeles County, California

- Buildings and structures in Simi Valley, California

- Environmental disasters in the United States

- Disasters in California

- Civilian nuclear power accidents

- Radioactively contaminated areas

- Environment of California

- 1947 establishments in California

- History of Los Angeles County, California

- History of Ventura County, California

- History of the San Fernando Valley

- History of Simi Valley, California

- Canoga Park, Los Angeles

- West Hills, Los Angeles

- San Fernando Valley

- Santa Susana Mountains

- Nuclear research reactors

- Nuclear accidents and incidents in the United States