Grand Slam (bomb)

| Grand Slam | |

|---|---|

A Grand Slam bomb being handled at RAF Woodhall Spa in Lincolnshire | |

| Type | Earthquake bomb |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1945 |

| Used by | Royal Air Force |

| Wars | Second World War |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Barnes Wallis |

| Designed | 1943 |

| Manufacturer | Vickers, Sheffield Clyde Alloy/Steel Company of Scotland, Blochairn, Glasgow |

| Produced | 1944–1945 |

| No. built | 42 used, 99 built by Clyde Alloy and the A. O. Smith Corporation of America[1]

|

| Variants | M110 (T-14) 22,000-lb GP Bomb (United States)[3] |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 22,000 lb (10,000 kg) |

| Length | 26 ft 6 in (8.08 m) |

| length | Tail 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) |

| Diameter | 3 ft 10 in (1.17 m) |

| Filling | Torpex D1 |

| Filling weight | 9,500 lb (4,300 kg) |

Detonation mechanism | penetration: earth 40 m (130 ft); concrete 6 m (20 ft)[4] |

| Blast yield | 6.5 long tons (6.6 t) TNT equivalent |

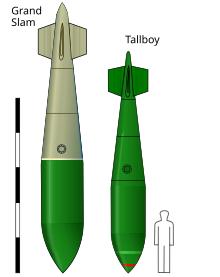

The Bomb, Medium Capacity, 22,000 lb (Grand Slam) was a 22,000 lb (10,000 kg) earthquake bomb used by RAF Bomber Command against German targets towards the end of the Second World War. The bomb was originally called Tallboy Large until the term Tallboy got into the press and the code name was replaced by "Grand Slam". The bomb was similar to a large version of the Tallboy bomb but a new design and closer to the size that its inventor, Barnes Wallis, had envisaged when he developed the idea of an earthquake bomb.

Medium Capacity (M.C.) bombs were designed to remedy the shortcomings of General Purpose (G.P.) bombs, with a greater blast and casings which were robust enough to confer a considerable capacity to penetrate, especially the Tallboy and Grand Slam. The Grand Slam case was made of a chrome-molybdenum alloy steel and had a charge-to-weight ratio of over 43 per cent.

Conventional Avro Lancaster bombers could not carry the bomb and 32 Lancaster B.Mk 1 (Special)s with more powerful engines, a stronger undercarriage, without bomb bay doors and minus many items to save weight, were built. When airborne with the Grand Slam a Special could barely manoeuvre and pilots were advised to refrain from minor adjustments of the flying controls, allowing the aircraft to wallow. A Lancaster which returned with its bomb was not permitted to land at RAF Woodhall Spa, the 617 Squadron base, but had to use the longer runway at RAF Carnaby.

From 14 March to 19 April 1945, 42 Grand Slams were dropped on Germany. When landing on reinforced concrete, the bombs tended to break up when they hit or explode prematurely. The bombs had been designed to land in soft ground, penetrate deeply and then explode, creating a camouflet, causing the structure above to subside. Grand Slams and Tallboys were capable of causing damage that smaller bombs could not, accelerating the collapse of German resistance and avoiding mass civilian casualties. Grand Slams were the most effective bombs used by the Allies until the advent of nuclear weapons later that year. After the war, the Royal Air Force and United States Army Air Forces used Grand Slams and other bombs for research.

Background

Medium Capacity bombs

Medium Capacity (M.C.) bombs were designed to address the shortcomings of General Purpose (G.P.) bombs, which had a charge-to-weight ratio of about 27 per cent (contemporary German bombs had a ratio of fifty per cent). M.C. bombs were to have a charge-to-weight ratio of at least forty per cent and use explosives of greater power, although shortages often led to inferior explosive types being used. High Capacity (H.C.) bombs had a charge-to-weight ratio of up to 75 per cent. M.C. bombs had greater blast effect than G.P. bombs but had casings which were robust enough to confer a considerable capacity to penetrate.[5]

Grand Slam

On 18 July 1943, after the Dams raid, the Controller of Research and Development at the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP) received a requirement for twelve Tallboy Small [4,000 lb (1,800 kg)] bombs, 60 unfilled Tallboy Medium (Tallboy) bombs and 100 Tallboy Large. Lack of capacity led to work on the Tallboy Large being stopped on 30 September. Interest in the Tallboy Large, renamed Grand Slam on 22 November 1944, after the term Tallboy appeared in the press, increased after better understanding of the effect of the Tallboy was gained by the inspection of targets in Europe. The Tallboy was discovered to be too small to destroy concrete buildings with direct hits; only near misses which opened a camouflet under the foundations were found to be effective. In September 1944 the German V-2 rocket bombardment of London began, which had been expected by the British since Operation Hydra, the attack on the Peenemünde research centre, on the night of 17/18 August 1943 and Grand Slams were considered as a weapon to be used on V-2 launch sites.[6]

Doubts remained at the Air Ministry; an officer in the planning department was sceptical, even with the discovery of the limits of the Tallboy bomb, about what the Grand Slam could be used on and whether when ready in February–March 1945, there would be anything left to bomb. Aircraft adapted to carry the Grand Slam could not carry any other load. Air Commodore Christopher Bilney replied that the Tallboy Large would be more useful than the Upkeep mine used in the Dams raid. At the Bomber Command headquarters in High Wycombe, there was a debate about how many Tallboy Larges to order, which ranged from 25 a month to 75. The head of Bomber Command, Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, thought that the new bomb might be useful against U-boat pens and the bigger targets of Operation Crossbow (anti-V-weapons attacks) but put the burden on the Air Ministry to decide how many to manufacture. In September the decision to make the new bombs was made and 600 were ordered in October; 200 from British sources and 400 from the US. The British order was cancelled on 4 October, leaving only US production, but RAF representatives in the US were able to persuade the Americans to build fifty bomb casings by the end of the year, to be filled in Britain. Four Lancaster bombers for trials were ordered then this was cut to one aircraft. During the Battle of the Bulge (16 December 1944 – 25 January 1945) any complacency about an imminent end to the war was confounded; the Grand Slam production order was revised again for 25 from British sources and 200 from the US.[6]

An expanded version of the Tallboy design was not feasible and the English Steel Corporation of Sheffield began work on "large boilers" in late 1944. Experiments with the composition of the bomb casing to find one that could withstand the shock of impact, a steel alloy of chromium-molybdenum. A concrete core, accurate to 1/10,000th of an inch was made, then a sand-covered outer mould was created, into which the molten metal was poured. The core was chipped out after the metal had cooled but hot places on the casing could result in structural flaws, breaking the bomb casing when it hit, with no guarantee of the detonation of its contents. The US casings were made by electric resistance welding but both types had to pass stress tests to weed out inadequate examples. The British-made casings were sent 100 mi (160 km) on specially-built road trailers, the nose on one and the tail on another, to be machined.[7]

The 12.1 ft (3.7 m) nose sections were filled by upending them to pour in 9,200 lb (4,200 kg) of Torpex explosive a bucketful at a time. Once the tail section was connected, the Grand Slam was 25.5 ft (7.8 m) long, 3.10 ft (0.94 m) at its widest diameter and weighed 22,400 lb (10,200 kg).[7] As with the Tallboy, the fins of the Grand Slam were angled and generated a stabilising spin and the Grand Slam had a charge-to-weight ratio of 43 per cent.[8] Four fuzes were provided, one specially made for the Grand Slam with an 11-second delay, the No. 53 with a thirty-minute delay, a No. 53A with an hour's delay and a No. 37 which had a delay of 6–144 hours. The first bomb arrived at Woodhall Spa on 20 January and fifteen were expected by the beginning of February.[7]

Lancaster B.Mk 1 (Special)

The ten remaining Dambuster Lancasters were sent for storage at the end of 1944 and 617 Squadron was increased from two fights to three, at the expense of 51 Squadron, a Halifax squadron of 4 Group, which lost a flight. To carry the Grand Slam, specially modified Lancasters were necessary but these would have to be subtracted from the production of conventional Lancasters, at a time when several 5 Group squadrons were converting to Lancaster from Halifaxes. The weight of the Grand Slam meant that only new aircraft would be able to carry it, rather than converting existing and worn aircraft and 32 B.Mk 1 (Special)s were ordered from Avro. There was little agreement on what equipment the specials should carry and Avro backslid on production to get the new Avro Lincoln, a Lancaster derivative, on schedule. Work began on the specials at the end of January 1945 and two had been built by 13 February, twelve were due within ten days, 24 by month's end and the remainder in March.[9]

PB995 was sent to the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) with PB592/G, a conventional B.Mk 1 built in 1944, which was to be modified to be a B.MK 1 (Special). Some equipment did not need to be fitted but other items were removed, which began a period of removals and reinstatements. A conference on 25 February was necessary to sort out the confusion. The front and mid-upper turrets were to go, along with the H2S, its fairing and the TR1196 R/T set, electric lights, flare chutes, flame dampers, some of the fuel tanks, the rear turret armour, three fire axes, a toolkit and the crew ladder. The commander of 5 Group, Air Vice-Marshal Ralph Cochrane ordered that the Identification friend or foe (IFF) be got rid of in favour of the VHF Bomber Fixer. Despite bombing by day, navigation equipment was needed because of the north-west European climate; GEE and LORAN were to be carried along with high-altitude and low altitude radio altimeters. The recognition lights and some of the usual VHF equipment were to stay along with the rear guns and 6,000 rounds of ammunition. The bomb doors had to go as even the widened Tallboy bomb doors would not fit a Grand Slam and as the mid-upper gunner and wireless operator were redundant, the crew was cut to five men.[10]

While carrying a Grand Slam, a Lancaster would be incapable of taking evasive action and Fishpond tail-warning radar went with the H2S set. As Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighters were operating in northern Germany, an Automatic Gun-Laying Turret (AGLT; also Village Inn or Z Equipment) was considered. The AGLT rear turret had been under test by the Bomber development Unit and two Main Force squadrons of 1 Group, which found that they restricted the view of the rear-gunner; the radar gun laying device was also unable to discriminate between German fighters and friendly bombers and bombers with the turret only flew when not in the company of other Allied aircraft. The aircraft of several bomber groups had been fitted with AGLT transmitters and worked best as an early-warning device and the B.Mk.1 (Special)s were fitted with AGLT in the nose. With a fuel load of 5,120 lb (2,320 kg) the Special would weigh 39,750 lb (18,030 kg) and the first was delivered to RAF Woodhall Spa, the base of 617 Squadron in Lincolnshire, on 25 February. There were still arguments about what the Specials would carry, when it was found that Avro had failed to install GEE sets. It was agreed to remove the front turret and its accoutrements; heating was needed for the rear guns and the Stabilised Automatic Bomb Sight had Tallboy dropping equipment but no capacity to drop practice bombs which needed to be incorporated. The TR1154 W/T was to be replaced by VHF R/T.[11]

Prelude

B.Mk1 (Special) in flight

In March Lancaster wheels and tyres were replaced by those of the heavier Avro Lincoln and the maximum weight of the Special was set at 72,000 lb (33,000 kg) with a maximum landing weight of 60,000 lb (27,000 kg) excepting emergencies. The commander of 617 Squadron, John "Johnny" Fauquier, ordered that if returning with a bomb, the Special would divert from Woodhall Spa and use the longer runway at RAF Carnaby near the coast at Bridlington in East Yorkshire.[12] The centre of gravity when loaded with a Tallboy or Grand Slam was within the aircraft design limits, provided the rear turret was retained. Merlin 24 engines [1,610 hp (1,200 kW) at 3,000 rpm, 1,510 hp (1,130 kW) at 3,000 rpm, +18 psi (120 kPa) boost at 9,250 ft (2,820 m)] were to equip the Special, fitted with paddle-bladed propellers. Particular attention was to be paid to the skin of the wings and rear fuselage when checking the airframe and the Special would take off only from smooth runways and always with experienced pilots. Fuel was to be used from inboard tanks to outboard ones to relieve the stresses on the wings.[13]

When the store is carried the aircraft is to be very carefully handled and is restricted to gentle manoeuvres only. At weights in excess of 67,000lb there is a tendency for the aircraft to wallow, but use of the controls may aggravate this, and no move should be made to correct it.[14]

The Specials were to have day bomber camouflage, the black underside being painted in Sky a pale green shade with the upper surfaces keeping the usual dark green and dark earth. To discriminate between Tallboy and Grand Slam Lancasters, the Tallboy aircraft kept the code letters KC and the Specials were coded YZ.[13]

Grand Slam handling

A Ramsome Rapier crane at the A&AEE could lift the Grand Slam when on a concrete base and the Type H trolley was acceptable when limited to 10 mph (16 km/h) with its tyres at 80 PSI. The bomb cradle on the trolley was tilted up at the front to protect the bomb bay roof from damage by the tailfins of the bomb. The bomb was raised into the bomb bay by a crew of six men, who took 35 minutes. Templates were manufactured to help align the bomb in the bay, the front one proving unnecessary and being dispensed with; the rear template was hung from the bomb bay roof. The inside of the Special bomb bay was faired with quick-release panels from the bomb door hinges to the underneath of the fuselage floor to protect pipe-work.[13]

The top of the bomb bay had metal plates installed, the forward bulkhead was faired to the contour of the nose of the Grand Slam and another fairing was fitted to the rearward bulkhead to smooth the airflow as it exited the bay. The usual bomb bay switches were replaced by a master switch; a release cable and lever were fitted to the left hand side of the cockpit for emergencies. The bomb was connected to the bay with a sprung dowel sticking out of the bomb bay roof and a Vickers release unit with metal links, which could be adjusted from within the aeroplane, wrapped around the bomb and released electrically or manually. Fuzing devices in the bomb bay roof worked for the Tallboy as well as the Grand Slam. The new bomb had a two-piece metal skirt between the bomb proper and the tail unit, whose front edge jutted out from the casing of the bomb. As the bomb fell, the slipstream could detach the tail unit of the bomb and the A&AEE advised that it be redesigned.[13]

The bomb dump at Woodhall Spa had been limited to forty Tallboys but room was made to accommodate ten Grand Slams by removing ordnance not in use. In February the A&AEE used PB592/G, a Lancaster B.Mk1, to test loading the Grand Slam using the Type H bomb trolley, which had been designed for the Tallboy and Grand Slam. When the first bomb was moved with an Allen crane, its front wheels rose from the ground as the bomb was lifted and the bomb could not be lowered smoothly, only by unlocking and locking the brake, which dropped the bomb 2 ft (0.61 m) each time. The armourers used a US Bay City crane afterwards with a power-lowering unit added early in 1945.[15]

Grand Slam test

The A&AEE at RAF Boscombe Down had only one bomb to test, with 617 Squadron standing by with the rest, ready to commence operations. The bombing range at the Ashley Range in the New Forest had a concrete target about 20 ft × 20 ft (6.1 m × 6.1 m), to be bombed preferably from the optimum height of 22,000 ft (6,700 m). PB955 was loaded with the Grand Slam to be flown by Group Captain H. A. (Bruin) Purvis; bad weather led to two failed attempts to bomb due to mist obscuring the target. On the third attempt, PB592/G, flown by Squadron Leader Headley (Hazel) Hazelden, managed to drop the bomb on 13 March. The aim of the crew was accurate for distance and observers saw the black and white painted bomb rotate as it fell, about 100 ft (30 m) off line to starboard.[16] After release, the Grand Slam accelerated to 1,049 ft/s (320 m/s), near supersonic, penetrating deep underground before detonating.[17] The bomb exploded and left a crater 124 ft (38 m) in diameter and 34 ft (10 m) deep; 617 Squadron was phoned from a nearby pub and told of the success; formal permission to use the bomb was given on 22 March and operations began the same day.[16]

Grand Slam operations, 1945

Bielefeld, 14 March

By mid-March 1945, over 3,500 long tons (3,600 t) had been dropped on the Bielefeld viaduct in 54 attacks and damage from 17 hits in one raid was repaired in 24 hours.[18] After an abortive attempt against viaducts at Arnsberg and Bielefeld on 9 March the bombers returned on 13 March, when 9 Squadron and 617 Squadron sent 19 Lancasters each against the same targets, two of the 617 Squadron aircraft carrying Grand Slams, escorted by 75 Mustang Mk IIIs (P-51Cs) from 11 Group.[19][a] The attack at Arnsberg by 9 Squadron was called off after two aircraft bombed and 617 Squadron turned back from Bielefeld after 129 Squadron (Mustang Mk IIIs) reported unbroken cloud all the way to the target.[19] On 14 March, fifteen Lancasters of 617 Squadron, carrying 14 Tallboys and a Grand Slam, all fuzed for 11 seconds' delay, tried again as fifteen 9 Squadron Lancasters made another attempt against the railway viaduct at Arnsberg. The weather was clear to the targets with some cloud around Bielefeld and a haze over both targets. Escorts from 11 Group consisted of 74 Mustang Mk IIIs and 8 (Pathfinder Force) Group provided four Oboe Mosquitos each from 105 and 109 squadrons to mark the targets. A Mosquito of 627 Squadron was present to film the attack.[20]

The Lancasters of 617 Squadron flew around Bremen then found that there was cloud on the north side of Bielefeld forcing PD112 S with the Grand Slam to attack from the south after resetting the SABS, followed by the photographic Mosquito. One of the 105 Squadron Oboe Mosquitoes dropped four 250 lb (110 kg) Target Indicator bombs which landed about 300 yd (270 m) to the south-south-west of the target. At 4:28 p.m. and from 11,965 ft (3,647 m), a far from ideal height, the Grand Slam fell from PD112 S, which jumped 500 ft (150 m) higher at the loss of weight. After 35 seconds, the bomb hit the ground about 30 yd (27 m) short and exploded the site erupting as the Tallboys came down. The pilot of the photographic aircraft, which recorded the attack from 4:15 to 4:35 p.m., shouted "You've done it!". The effect of the Grand Slam could not be distinguished from that of the eleven Tallboys but photographic reconnaissance by a Spitfire from 542 Squadron, following the bombers, then a Mosquito from 540 squadron later on, showed that 200 ft (61 m) of the north viaduct and 260 ft (79 m) of the south viaduct had been demolished, depositing about 20,000 long tons (20,000 t) of rubble into the valley.[21][b]

Arnsberg, 15 March

On 15 March, in a haze with some cloud over the target, two aircraft of 617 Squadron with Grand Slams fuzed for 11 seconds' delay and 14 Lancasters of 9 Squadron, carrying Tallboys, attacked the railway viaduct at Arnsberg again. A close fighter escort of 34 Mustang Mk IIIs was provided by 11 Group. A photographic Mosquito, KB433, was laid on by 627 Squadron and another 141 fighters were in the vicinity covering raids by 4, 6 and 8 Groups.[23][c] The 425 ft (130 m) long viaduct, built from brick and stone faced with concrete, crossed the Ruhr in five spans. In poor visibility the crew of the photographic Mosquito saw that "the whole force made one run into sun and one bomb seen to drop". This was the first Grand Slam, dropped from 13,000 ft (4,000 m) at 4:58 p.m.[23]

The photographic crew reported, "Second run into sun and one or two bombs fell. Individual runs then made. No direct hits seen. Majority of bombs fell to the east....". The second Grand Slam was brought home after several bomb runs because of the haze and the Lancaster, PB996, landed at the emergency bomber landing ground at RAF Manston. Ten Tallboys were also dropped with no effect and no aircraft were lost.[25] On the return journey the port inner propeller of NG384 over-speeded and could not be feathered and then oil leaking out from behind the propeller caught fire and the pilot, Flight-Lieutenant F. A. Jones ordered the crew to abandon the aircraft 15 mi (24 km) south of the target. Four of the crew parachuted but then the fire went out and Jones force-landed at Gosselies near Charleroi.[23]

Arnsberg, 19 March

On 19 March, 19 Lancasters of 617 Squadron, six with Grand Slams and 13 with Tallboys, attacked the viaduct again as 9 Squadron attacked the Vlotho rail bridge, in fairly cloudy weather at high altitude, with thin patches lower down. The bombers were escorted by 88 Mustang IIIs from 11 Group.[26][d] PD329 Y, a Lancaster without bombs from 463 Squadron carried two cameramen from the RAF Film Unit accompanied 617 Squadron. A report from 129 Squadron, part of the escorting Mustang force, called the bomber formation tight but then the bombers flew into cloud at 14,000 ft (4,300 m). The squadron flew over the Möhne Dam with its barrage balloons, smoke screen and anti-aircraft fire. The cameramen in PD329 Y had been briefed to film PB966 C, flown by Flight-Lieutenant P. H. Martin and formated on its starboard side, with a cameraman in the nose turret to film the Grand Slam as it fell away and the other on the floor of the fuselage filming vertically. Closer to the target, PD329 Y dropped back and flew on the port quarter of PB966 C.[28]

The bomb was not to be dropped from under 14,000 ft (4,300 m) but Martin, the pilot, could not coax the bomber above 12,700 ft (3,900 m). On its five-minute bombing run, Martin had to fly within the tolerances of its SABS bombsight, within 0.5 mph (0.80 km/h) of airspeed and +/- 10 ft (3.0 m) of altitude. The cameramen started filming and when the bomb dropped, PB966 C jumped 600 ft (180 m) higher. The bomb began its spin and came down on the western span, which disintegrated, along with the roofs of buildings nearby. All but one Lancaster of the first wave, whose Tallboy hung up, bombed. A second wave bombed fairly accurately but one Grand Slam fell 50 yd (46 m) off line due to a SABS fault. Two spans of the bridge, about 100 ft (30 m) long and one pier had been destroyed, the track on the west bank had been cut, 115 ft (35 m) of one of the embankments had been shoved out of line and the entrance to a tunnel on the east bank had been blocked; no damage had been caused to a Red Cross camp nearby.[29] After the war the casings of a Grand Slam and a Tallboy were found at the site; the Grand Slam was thought to have landed flat on a road and only the explosive at the rear of the casing detonated; the Tallboy hit a wall, broke up and buried itself in the ground without going off.[30]

Arbergen, 21 March

Twenty Lancasters of 617 Squadron, two carrying Grand Slams and the rest Tallboys, flew in good weather with little cloud to Bremen to attack the double-tracked railway bridge at Arbergen which crossed the Weser near Nienburg. The bridge was 200 yd (180 m) long with three steel girder spans. The railway approached the river from the south-west along an embankment until 460 yd (420 m) from the river where it crossed a meadow on a low-lying steel viaduct resting on piers. The bombers were escorted by twenty Mustang Mk IIIs of 306 (Polish) Squadron and 309 (Polish) Squadron. Another five fighter squadrons were provided to escort a day raid by 1 and 8 Groups on an oil refinery at Bremen; other Main Force aircraft attacked targets in Münster and Rheine.[31]

The first Grand Slam was dropped from 13,000 ft (4,000 m), landing 30 yd (27 m) short and the second fell 200 yd (180 m) off target to the north, due to flak (anti-aircraft fire) and aiming problems. The Tallboys hit the middle of the bridge and the ends were blown off their piers; the pier to the east collapsed onto the ground and the western pier was twisted and sagged to the ground at one place; part of the railway track, above the embankment and the first pier on the west side, was wrecked. One Lancaster was shot down near Okel and left a crater 33 ft (10 m) deep; five Lancasters were damaged by flak and an attack by a Me 262 jet fighter.[32]

Nienburg, 22 March

Twenty Lancasters of 617 Squadron, six carrying Grand Slams fuzed for 25–30 seconds' delay and 14 with Tallboys with 25–35 seconds' or one-hour delay fuzes, attacked the railway bridge at Nienburg, between Bremen and Hanover, in atmospheric conditions ideal for bombing. A railway bridge at Bremen was attacked at the same time by 9 Squadron with Tallboys. The bombers were escorted by 114 Mustang Mk IIIs and 69 Spitfire Mk IXs from 11 Group squadrons.[33] The Lancasters of 617 Squadron bombed within one minute, dropping five Grand Slams and twelve Tallboys. One Lancaster crew claimed a near miss with a Grand Slam and another crew claimed a hit.

The first large bomb hit the bridge on the AP, [aiming point] and blew the bridge up. It collapsed in the water at the eastern end. There was a further direct hit in the centre.

— Pilot Officer M. B. Flatman[34]

It had been planned that the fourth and eight rows of Lancasters would not bomb on the first pass and Flight Lieutenant L. S. Goodman reported that on the second bomb run the bridge was under water, the spans having been broken or blown off their piers.[34] A third Lancaster crew found that their bomb would not drop despite two attempts and the bridge collapsed before the third try, leaving the crew to take it home. A fourth Grand Slam was reported to have hit the east end of the structure. Reconnaissance photographs showed that the bridge had been destroyed.[35]

Bremen, 23 March

Another railway Bridge near Bremen was attacked later in the day by twenty 617 Squadron Lancasters, six carrying Grand Slams and 14 with Tallboys. The bridge at Bad Oeynhausen was attacked by 9 Squadron. The weather was clear and ideal for bombing but was also good for the Bremen anti-aircraft defences. The bombers were escorted by 41 Mustang Mk IIIs from 11 Group with seven more squadrons in the vicinity.[36][e] A total of 128 Lancasters took part in the bombing from 1 Group and 5 Group, most accompanying 617 Squadron on the attack on the bridge at Bremen. The Germans started to generate a smoke screen but were too late; two hits were observed before the smoke screen and wreckage blocked the view. The pitch control on one of Lancaster PB996's engines made the aircraft lose speed and its bomb was dropped on a jettison area; the pilot of PD112 decided to bomb despite the bomb-aimers clear vision panel being smashed by flak .[37]

Three hits were claimed and one Tallboy hung up when the bomb aimer tried to drop it then fell off 15 seconds later, overshooting the bridge. Later analysis found that a Tallboy had landed on the bank at the south end of the bridge about 100 ft (30 m) from the abutment and the shock of the explosion shifted it, making the span fall into the river. A Tallboy hit the north end of the bridge, the damage being swiftly repaired; another 250 yd (230 m) to the south which was filled in and new track laid. Eventually the Germans demolished the bridge to create an obstacle to the Allied ground advance.[37] Lancaster NG489 was hit by flak and the crew jettisoned the Grand Slam to regain control. Several other Lancasters were hit by anti-aircraft fire and four others were attacked by Me 262s, fifteen of which were seen on the flight to the target.[38][f]

Farge, 27 March

Twenty Lancasters of 617 Squadron, 13 carrying Grand Slams, the remainder carrying Tallboys, attacked the Valentin submarine pens in clear visibility escorted by 90 Mustang Mk IIIs of 11 Group.[40][g] Since October 1944, building work had been seen at Farge, a village on the Weser river, 5 mi (8.0 km) north of Vegesack and 10 mi (16 km) north-west of Bremen. The building had 96 ft (29 m) of the structure above ground and 41 ft (12 m) below, was 1,375 ft (419 m) long and 315 ft (96 m) wide, enclosing 1,400,000 cu yd (1,100,000 m3) of space. The walls and roof were made of reinforced concrete with arched trusses on the walls, filled with concrete.[41] The roof was about 15 ft (4.6 m) thick and was being reinforced to a thickness of 23 ft (7.0 m). Farge was intended for the assembly of type XXI U-boats. The shipyard Bremer Schiff und Maschinenfabrik (Bremer Vulkan) at Vegasack and the site of the building, was code named Valentin, construction beginning early in 1943. The site was chosen because it was on the convex side of a curve in the river less prone to silting; the river bed was dredged to a depth of 23 ft (7.0 m) to allow submarine sections in on barges and assembled U-boats out.[42]

Production was expected to begin in March 1945, full production to be achieved in August; the schedule had slipped but production was to start within two months.[42] One Lancaster had returned soon after take-off and another turned back over the target with engine-trouble, ditching the Grand Slam in the North Sea. Moderate to heavy flak was encountered by the gaggle of Lancasters but there was no fighter opposition. The bombs were dropped in about a minute and despite 1-hour delay fuzes, three bombs exploded immediately. Two of the fourteen hits on the pens were by Grand Slams and one by a Tallboy, the hits landing on the un-thickened part of the roof on the west side. The Grand Slams penetrated 8 ft (2.4 m) into the concrete causing about 1,000 long tons (1,000 t) of the roof to fall in bringing down two moveable cranes. The thickened part of the roof and a periscope-testing tower were also damaged. One bomb damaged power stations, concrete mixing facilities and shelters on the north side. Marines who had been inside the building reported later that there was a huge concussive effect, which severely depressed their morale; no aircraft were lost.[43]

Hamburg, 9 April

Seventeen Lancasters from 617 Squadron were dispatched to bomb the Finkenwerder U-boat pens in Hamburg, two with Grand Slams and the rest with Tallboys.[44] The pens were inside a 500 sq ft (46 m2)-building with a roof 11.5 ft (3.5 m) thick, reinforced by steel beams and trusses. Forty Lancasters from 5 Group were to bomb oil storage tanks nearby.[45] The weather was clear with some haze, a thin layer of cirrus clouds above the city but the visibility was very good. A fighter escort from 11 Group consisted of 120 Mustang Mk III, 30 Mustang Mk IV, 59 Spitfire Mk IX and 24 Spitfire Mk XVI to counter any attempts by Me 262 jets to intervene.[46][h] Luftwaffe fighters, including jets, attempted to intercept the formation and there was much flak, which damaged six Lancasters before they bombed.[44] Buildings to the north and west were hit and a reconnaissance photograph showed seven hits, four penetrating the roof.[45]

A post-war report recorded six hits by Tallboys, the two Grand Slams and the other Tallboys landing in the water. The six Tallboys had penetrated the roof part way, hit girders and exploded, blowing holes through the ceiling and depositing hundreds of tons of concrete into the pens. There had been 3,000 people inside the pens, fewer than usual, because it was Poets Day, when German workers left at 4:00 p.m.; 27 people were killed, about sixty were seriously injured and a panic ensued; U-906 and U-1192 were damaged. About thirty Me 262s appeared and 467 Squadron RAAF, on the oil tanks raid, accelerated and turned, ending up bumping along behind the 617 Squadron slipstream. The Mustangs jettisoned their drop tanks and 122 Squadron bounced the German jets which raced away. The Polish 306, 309 and 315 squadrons attacked the jets and claimed three Me 262s shot down and three damaged; two Lancasters were shot down.[47]

Heligoland, 19 April

The coastal gun-batteries on the islands of Heligoland and Düne in the Heligoland Bight, the south-eastern extremity of the North Sea, were attacked on 19 April. The military installations on the main island comprised a radar installation covering the Elbe and Weser rivers, an airfield and a coastal battery each of 12 in (300 mm) and 6 in (150 mm) guns. To ensure that Allied ships could enter the Elbe and Weser estuaries, Bomber Command intended to attack the island with 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs but at least forty heavy anti-aircraft guns on the islands had to be silenced. The gun positions had a diameter of about 60 ft (18 m) and only hits or near misses would be effective. On 18 April 969 bombers had attacked the anti-aircraft guns but some remained operational. On 19 April, 20 Lancasters of 617 Squadron attacked with six Grand Slams and fourteen Tallboys and 16 Lancasters from 9 Squadron carried Tallboys fuzed for 25 seconds' delay.[48]

A Mosquito from the RAF Film Unit accompanied the raiders and a fighter escort was provided by 11 Group and 12 Group, consisting of 11 Mustang Mk IIIs, 42 Spitfire Mk IXs and 26 Spitfire XVIs.[49][i] The gun emplacements were at the north and south ends of the island and three aiming points were chosen, two for 9 Squadron and one for 617 Squadron. Thin stratocumulus cloud was encountered from 3,000–4,000 ft (910–1,220 m) and six of the 9 Squadron bombers were to act as wind finders, the results being broadcast to the rest of the squadron at H-5. As 9 Squadron flew towards the island they were surprised to see 617 Squadron attacking, climbed 1,000 ft (300 m) out of the way and circled while waiting for their fighter escort. The attack by 617 Squadron was made in two waves against hardly any anti-aircraft fire and all bar one aircraft bombed. Photographic evidence showed two hits on aiming point H and several near misses, which added to the damage. Another attack by the Main Force was planned but the war ended before it took place.[51]

Aftermath

Analysis

In 1991, Alan Cooper wrote that during March 1945, 156 day-sorties were flown, 31 with Grand Slams and 40 with Tallboys. An analysis of the bombing accuracy of 617 Squadron and 9 Squadron on Tallboy sorties found that, using different bomb sights and bombing from heights between 9,000 and 17,000 ft (2,700 and 5,200 m), 1 per cent of the Tallboys dropped by 617 Squadron were gross errors [defined as missing the aiming point by more than 400 yd (370 m)] against 10 per cent of the Tallboys dropped by 9 Squadron.[52] Unlike the Tallboy, the Grand Slam was designed to penetrate concrete roofs and was more effective against fortifications than earlier bombs.[53] By the end of the war, 41 Grand Slams had been dropped on operations although in 2004, Stephen Flower wrote of 42 bombs, a figure he repeated in his 2013 publication.[54]

When the success [of the Tallboy bomb] was proved, Wallis designed a yet more powerful weapon… This 22,000 lb bomb did not reach us before the spring of 1945, when we used it with great effect against viaducts or railways leading to the Ruhr and also against several U-boat shelters. If it had been necessary, it would have been used against underground factories, and preparations for attacking some of these were well advanced when the war ended.

— Sir Arthur Harris (1947).[55]

In 2013, Stephen Flower wrote that when dropped on buildings fortified with reinforced concrete the Grand Slam tended to break up on impact or go off too soon. Flower wrote that it was not surprising that the Grand Slam was limited in effect when dropped on concrete, when it was designed to fall on earth and then explode under the foundations of buildings, creating a camouflet for the structure to subside into. The Grand Slam and Tallboy bombs did cause damage that conventional bombs were incapable of and had a great disruptive effect on the means of resistance available to the Germans, limiting the development of new weapons with which to continue the war. In 2013, Stephen Flower wrote that the earthquake bombs rarely caused mass civilian casualties and were the most effective bombs used in the war, until the advent of nuclear bombs later in 1945.[56]

Operation Front Line/Project Ruby

Beginning in March 1946, Operation Front Line (British title) / Project Ruby (US title), was a plan to investigate the use of penetration bombs against reinforced concrete targets. The Valentin U-boat pens near Bremen were chosen, having been abandoned after the attack on 27 March 1945. Since 9 Squadron and 617 Squadron had been transferred to the Far East to join Tiger Force, Grand Slams were carried by Lancasters from 15 Squadron, into whose C Flight, the 617 Squadron crews not sent abroad were moved with their B.Mk 1 (Specials) and their SABS bomb sights. The Watten bunker, in the Pas de Calais, which has been used for Royal Navy Disney bomb tests, was bombed with Grand Slams.[56]

In May 1946, Operation Front Line began with the participation of US B-29 bombers. Tallboy and Grand Slams were dropped on the Valentin pens and Heligoland; only two hits were achieved from thirteen bombings. The RAF and USAAF reports concluded that none of the bombs were effective against reinforced concrete and suggested more tests in 1947. The tests were resumed after 15 Squadron had finished dropping fifteen bombs on a battleship for the RN. The squadron was down to six Lancasters, four being B.Mk 1 (Special)s, not capable of carrying the 1,650 lb (750 kg) bombs being tested. The other two could carry the bomb but 15 Squadron was re-equipping with Avro Lincolns and six of these were to be altered to carry SABS and radar altimeters. Three USAF B-29s participated again to drop the 1,650 lb (750 kg) bombs from 30,000 ft (9,100 m) which was above the ceiling of the SABS.[56]

The B-29s were also to drop the new US Amazon II and Samson bombs, both 25,000 lb (11,000 kg), in Operation Ruby II, later called the Harker Project. Photographs taken by 542 Squadron, a photographic reconnaissance unit, before the Grand Slam attack during the war were used to stake out the target with red flags and cameras was set up to film the drops. On 4 August the B-29s achieved six 1,650 lb (750 kg) bomb hits from 30,000–35,000 ft (9,100–10,700 m) and five Amazon II hits out of fifteen from 17,000 ft (5,200 m). From 20 September, 15 Squadron Lincolns dropped the 1,650 lb (750 kg) bomb and achieved seven hits, some of which broke on the roof. Tests with a 1,000 lb (450 kg) obtained three hits out of seven.[56]

Examples

Five Grand Slam bombs are preserved and displayed in Britain at the RAF Museum, London, Brooklands Museum, RAF Lossiemouth, Dumfries and Galloway Aviation Museum and the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight Visitors' Centre at RAF Coningsby. Casings, without their tails, can be seen at the Kelham Island Museum in Sheffield and Yorkshire Air Museum at Elvington. The T-12 Cloudmaker is an American-made variant of the Grand Slam and an example is displayed at the Air Force Armament Museum in the United States.[3]

See also

Notes

- ^ Escorts from 118, 122, 129, 165 and 234 squadrons RAF, 309, 315 and 316 (Polish) squadrons.[19]

- ^ A Tallboy fell off a Lancaster when its bomb bay doors were opened, one Lancaster crew bombed a road junction 750 yd (690 m) from the viaduct by mistake and one crew brought their bomb home after the bomb-sight failed at the last moment.[22]

- ^ The escorts were from 306, 309, 315 (Polish) squadrons and 234 Squadron RAF.[24]

- ^ Escorts came from 118, 122, 129, 165 squadrons (RAF), 306, 309, 316 (Polish) and 234 Squadron RAF.[27]

- ^ 122 Squadron RAF, 306, 309 and 316 (Polish) squadrons.[36]

- ^ Jon Lake wrote in 2002 that two Grand Slams struck the bridge.[39]

- ^ Fighter escorts from 64, 118, 122, 126, 129, 165, 234 squadrons RAF and 316 (Polish) Squadron.[40]

- ^ 118, 122, 124, 129, 165 and 234 squadrons RAF, 306 and 309 (Polish), 310, 312 and 313 (Czech), 315 and 316 (Polish), 441 and 442 RCAF, 602, 603 and 611 RAuxAF.[46]

- ^ Fighters from 309 (Polish), 310, 312 and 313 (Czech), 602 and 603 squadrons RAuxAF.[50]

References

- ^ Flower 2004, appendix 4.

- ^ Webster & Frankland 1994, p. 203.

- ^ a b Ruby 1946, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Flight 1946.

- ^ Webster & Frankland 2006, pp. 31–33.

- ^ a b Flower 2013, p. 353.

- ^ a b c Flower 2013, p. 363.

- ^ Flower 2013, p. 366; Webster & Frankland 2006, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 353–355.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 355–356.

- ^ Flower 2013, p. 357.

- ^ Cooper 1991, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d Flower 2013, p. 359.

- ^ Flower 2013, p. 361.

- ^ Flower 2013, p. 365.

- ^ a b Flower 2013, pp. 366–367.

- ^ Webster & Frankland 1994, pp. 164, 181.

- ^ Cooper 1991, p. 147.

- ^ a b c Flower 2013, p. 369.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 369–370.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 370–372; Cooper 1991, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Webster & Frankland 1994, p. 204.

- ^ a b c Flower 2013, pp. 372–373.

- ^ Flower 2013, p. 373.

- ^ Cooper 1991, p. 148.

- ^ Cooper 1991, pp. 149–150; Flower 2013, p. 373.

- ^ Flower 2013, p. 374.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 378–379.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 380–381.

- ^ Cooper 1991, pp. 149–150; Flower 2013, pp. 380–381.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 381–382.

- ^ Flower 2004, pp. 340–342; Cooper 1991, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Cooper 1991, p. 151; Flower 2013, p. 384.

- ^ a b Flower 2013, p. 384.

- ^ Cooper 1991, p. 151.

- ^ a b Flower 2013, p. 385.

- ^ a b Flower2013, pp. 387–388.

- ^ Cooper 1991, p. 152; Flower 2004, pp. 344–347.

- ^ Lake 2002, p. 62.

- ^ a b Flower 2013, p. 388.

- ^ Cooper 1991, pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b Flower 2013, pp. 388–390.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 390–394; Cooper 1991, pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b Cooper 1991, p. 155.

- ^ a b Flower 2013, p. 398.

- ^ a b Flower 2013, p. 397.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 398–400.

- ^ Flower 2004, pp. 362–364.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 403–404.

- ^ Flower 2013, p. 404.

- ^ Flower 2013, pp. 403–405.

- ^ Cooper 1991, p. 154.

- ^ Flower 2004, p. 375.

- ^ Webster & Frankland 1994, p. 204; Flower 2004, Appendix 4; Flower 2013, p. 462.

- ^ Harris 2005, p. 252.

- ^ a b c d Flower 2013, pp. 418–419.

Bibliography

- "Bombs Versus Concrete". Flight. XLIX (1, 953). 30 May 1946. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Comparative Test of the Effectiveness of Large Bombs against Large Reinforced Concrete Structures (PDF) (Report). AAF Proving Ground, Eglin Field, Florida. 31 October 1946. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Cooper, A. W. (1991) [1983]. Beyond the Dams to the Tirpitz (pbk. Goodall Publications, London ed.). London: William Kimber. ISBN 0-907579-15-9.

- Flower, Stephen (2004). Barnes Wallis' Bombs: Tallboy, Dambuster & Grand Slam. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2987-6.

- Flower, Stephen (2013) [2009]. The Dambusters: An Operational History of Barnes Wallis' Bombs (e-book ed.). Stroud: Amberley Books. ISBN 978-1-4456-1828-9.

- Harris, Sir Arthur (2005) [1947]. Bomber Offensive. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military Classics. p. 252. ISBN 1-84415-210-3.

- Lake, Jon (2002). Lancaster Squadrons 1944–45. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-433-7.

- "The 'Gate Guards' at RAF Scampton's Main Gate in about 1958". Australian Armourers Association. 2004. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Webster, C.; Frankland, N. (1994) [1961]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Strategic Air Offensive Against Germany 1939–1945: Victory (Part 5). History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. III (facs. repr. Imperial War Museum Department of Printed Books and The Battery Press, London and Nashville ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-205-5.

- Webster, C.; Frankland, N. (2006) [1961]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Strategic Air Offensive against Germany 1939–1945: Annexes & Appendices. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV (facs. repr. The Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84574-350-5.

Further reading

- Kharin, D. A.; Kuzmina, I. V.; Danilova, T. I. (22 September 1972). "Ground Vibrations during Camouflet Blasts". Foreign Technology Division, Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio. AD0751247. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Levine, A. (1992). The Strategic Bombing of Germany, 1940–1945. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-94319-4.

- Middlebrook, M.; Everitt, C. (2014) [1985]. The Bomber Command War Diaries: An Operational Reference Book 1939–1945 (repr. Pen & Sword Aviation, Barnsley ed.). London: Viking. ISBN 978-1-78346-360-2.

- Nichol, John (2015). After the Flood: What the Dambusters Did Next. London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-810031-5.

- Ward, C. (2008). 5 Group Bomber Command: An Operational History (e-book ed.). Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. ISBN 978-1-84468-737-4.

External links

- Movietone News (Youtube com) Ten Tonner (video of a Grand Slam being dropped on the Bielefeld Viaduct)

- Wallis's Bombs – Big & Bouncy – www.sirbarneswallis.com

- A picture of a Lancaster carrying a Grand Slam

- Movietone News "Ten Tonner" – video of a Grand Slam being dropped on the Bielefeld Viaduct on youtube.com

- The hole left in the roof by a Grand Slam at the Farge U-boat pen