Chinese guardian lions

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

| Chinese guardian lions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

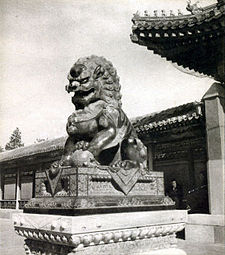

A Ming-era guardian lion in the Forbidden City | |||||||||

A Qing-era guardian lion pair in the Forbidden City. Note the different appearance of the face and details in the decorative items, compared to the earlier Ming version. | |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 獅(子) | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 狮(子) | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | lion | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 石獅(子) | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 石狮(子) | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | stone lion | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Khmer name | |||||||||

| Khmer | សឹង្ហ singha | ||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||

| Thai | สิงห์ sǐng | ||||||||

| Sinhala name | |||||||||

| Sinhala | සිංහ siṁha | ||||||||

| Burmese name | |||||||||

| Burmese | ခြင်္သေ့ chinthe | ||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||

| Tibetan | གངས་སེང་གེ gangs-seng-ge | ||||||||

Chinese guardian lions, or imperial guardian lions, are a traditional Chinese architectural ornament, but the origins lie deep in much older Indian Buddhist traditions. Typically made of stone, they are also known as stone lions or shishi (石獅; shíshī). They are known in colloquial English as lion dogs or foo dogs / fu dogs. The concept, which originated and became popular in Chinese Buddhism, features a pair of highly stylized lions—often one male with a ball which represents the material elements and one female with a cub—which represents the element of spirit, were thought to protect the building from harmful spiritual influences and harmful people that might be a threat. Used in imperial Chinese palaces and tombs, the lions subsequently spread to other parts of Asia including Japan (see komainu), Korea, Philippines, Tibet, Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Cambodia, Laos, and Malaysia.

Description

Statues of guardian lions have traditionally stood in front of Chinese Imperial palaces, Imperial tombs, government offices, temples, and the homes of government officials and the wealthy, and were believed to have powerful mythic protective benefits. They are also used in other artistic contexts, for example on door-knockers, and in pottery. Pairs of guardian lion statues are still common and symbolic elements at the entrances to restaurants, hotels, supermarkets and other structures, with one sitting on each side of the entrance, in China and in other places around the world where the Chinese people have immigrated and settled, especially in local Chinatowns.[citation needed]

The lions are usually depicted in pairs. When used as statuary the pair would consist of a male leaning his paw upon an embroidered ball (in imperial contexts, representing supremacy over the world) and a female restraining a playful cub that is on its back (representing nurture).[1]

Etymology

Guardian lions are referred to in various ways depending on language and context. In Chinese they are traditionally called simply shi (Chinese: 獅; pinyin: shī) meaning lion—the word shi itself is thought to be derived from the Persian word šer.[2] Lions were first presented to the Han court by emissaries from Central Asia and Persia, and were already popularly depicted as guardian figures by the sixth century AD.[3] Today the guardian lions are more usually specified by reference to the medium or material, for example:

- Stone lion (石獅; Shíshī): for a stone sculpture; or

- Bronze lion (銅獅; Tóngshī): for a bronze sculpture.

and less commonly:

- Auspicious lion (瑞獅; Ruìshī): referring to the Tibetan Snow Lion or good fortune

In other Asian cultures

- In Japan: the lion figures are known as Shishi (獅子, lion) or Komainu (狛犬, lion dogs)

- In Korea: known as Haetae

- In Myanmar and Laos: known as Chinthe and gave their name to the World War II Chindit soldiers

- In Cambodia: known as Singha or Sing (សឹង្ហ)

- In Sri Lanka: known as Singha (සිංහ මූර්ති)

- In Thailand: known as Singha or s̄ingh̄̒ (สิงห์)

- In Tibet: known as a Snow Lion or Gangs-seng-ge (གངས་སེང་གེ་)

- In Vietnam: known as Sư tử đá

Western names

In English and several Western languages, the guardian lions are often referred by a multitude of names such as: "Fu Dogs",[4] "Foo Dogs", "Fu Lions", "Fo Lions", and "Lion Dogs".[5] The term "Fo" or "Fu" may be transliterations to the words 佛 (pinyin: fó) or 福 (pinyin: fú), which means "Buddha" or "prosperity" in Chinese, respectively. However, Chinese reference to the guardian lions are seldom prefixed with 佛 or 福, and more importantly never referred to as "dogs".

Reference to guardian lions as dogs in Western cultures may be due to the Japanese reference to them as "Korean dogs" (狛犬・高麗犬) due to their transmission from China through Korea into Japan. It may also be due to the misidentification of the guardian lion figures as representing certain Chinese dog breeds such as the Chow Chow (鬆獅犬; sōngshī quǎn; 'puffy-lion dog') or Pekingese (獅子狗; Shīzi Gǒu; 'lion dog').

Appearance

The lions are traditionally carved from decorative stone, such as marble or granite, or cast in bronze or iron. Because of the high cost of these materials and the labor required to produce them, private use of guardian lions was traditionally reserved for wealthy or elite families. Indeed, a traditional symbol of a family's wealth or social status was the placement of guardian lions in front of the family home. However, in modern times less expensive lions, mass-produced in concrete and resin, have become available and their use is therefore no longer restricted to the elite.

The lions are always presented in pairs, a manifestation of yin and yang, the female representing yin and the male yang. The male lion has his right front paw on a type of cloth ball simply called an "embroidered ball" (繡球; xiù qiú), which is sometimes carved with a geometric pattern. The female is essentially identical, but has a cub under the left paw, representing the cycle of life. Symbolically, the female lion protects those dwelling inside (the living soul within), while the male guards the structure (the external material elements). Sometimes the female has her mouth closed, and the male open. This symbolizes the enunciation of the sacred word "om". However, Japanese adaptations state that the male is inhaling, representing life, while the female exhales, representing death. Other styles have both lions with a single large pearl in each of their partially opened mouths. The pearl is carved so that it can roll about in the lion's mouth but sized just large enough so that it can never be removed.

According to feng shui, correct placement of the lions is important to ensure their beneficial effect. When looking at the entrance from outside the building, facing the lions, the male lion with the ball is on the right, and the female with the cub is on the left.

Chinese lions are intended to reflect the emotion of the animal as opposed to the reality of the lion. This is in distinct opposition to the traditional English lion[clarification needed] which is a lifelike depiction of the animal. The claws, teeth and eyes of the Chinese lion represent power. Few if any muscles are visible in the Chinese lion whereas the English lion shows its power through its life-like characteristics rather than through stylized representation.

History

Asiatic lions are believed to be the ones depicted by the guardian lions in Chinese culture.[6]

With increased trade during the Han dynasty and cultural exchanges through the Silk road, lions were introduced into China from the ancient states of Central Asia by peoples of Sogdiana, Samarkand, and the Yuezhi (月氏) in the form of pelts and live tribute, along with stories about them from Buddhist priests and travelers of the time.[7]

Several instances of lions as imperial tributes from Central Asia were recorded in the document Book of the Later Han (後漢書) written from 25 to 220 CE. On one particular event, on the eleventh lunar month of 87 CE, "... an envoy from Parthia offered as tribute a lion and an ostrich"[8] to the Han court. Indeed, the lion was associated by the Han Chinese to earlier venerated creatures of the ancient Chinese, most notably by the monk Huilin (慧琳) who stated that "the mythic suan-ni (狻猊) is actually the lion, coming from the Western Regions" (狻猊即獅子也,出西域).[9]

The Buddhist version of the Lion was originally introduced to Han China as the protector of dharma and these lions have been found in religious art as early as 208 BC. Gradually they were incorporated as guardians of the Chinese Imperial dharma. Lions seemed appropriately regal beasts to guard the emperor's gates and have been used as such since. There are various styles of guardian lions reflecting influences from different time periods, imperial dynasties, and regions of China. These styles vary in their artistic detail and adornment as well as in the depiction of the lions from fierce to serene.

Although the form of the Chinese guardian lion was quite varied during its early history in China, the appearance, pose, and accessories of the lions eventually became standardized and formalized during the Ming and Qing dynasties into more or less its present form.

Gallery

-

A horn blower riding a guardian lion, Qing dynasty

-

One of the many 450-year old Foo dogs at San Agustin Church (Manila) in the Philippines.

-

One of the foo dogs of the current structure of the Basilica del Santo Niño in the Philippines built 287 years ago. The foo dog pair in the church are both male, similar to other churches in the islands.

-

A lion-like suanni depicted on the leg of an incense burner

-

A sitting lion statue, celadon, 11th to 12th century, Song Dynasty

-

A white stone shi (male)

-

Green guardian lions, Ming dynasty

-

Female guardian lion with her cub at the Summer Palace, Beijing- late Qing Dynasty, but in the Ming style

-

Cub detail

-

Standing lion at the Ming Dynasty Tombs Spirit Way

-

Statue of a mystical Chinese guardian lion in old Beijing, China

-

A guardian lion outside Yonghe Temple, Beijing

-

The Iron Lion of Cangzhou, cast in 953 AD, is the largest known and oldest surviving iron-cast artwork in China

-

A guardian lion in Pingxi District, Taiwan

-

A guardian lion of Wen Wu Temple, Taiwan

-

A pair of guardian lions of Gaoyi Que, 209 AD Han

-

Imperial guardian lion outside Ngee Ann City in Singapore

-

Guardian Lion, Brooklyn Museum, New York City

-

Guardian Lion in Saint Petersburg, Russia

Literary and pop-culture references

- In the novelet "White Magic" by Albert E. Cowdrey (Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, March 1998), the protagonist has a "foo" lion/dog that serves as his "familiar" and comes alive, when necessary, to protect him and his neighbors.

- In the planned spinoffs of the comics based on the Gargoyles Disney TV animated series, the "timedancing" gargoyle Brooklyn receives a green-skinned, leonine gargoyle beast that is named "fu-dog" from the Western name of the Chinese guardian lion statuary.

- Stone lions feature in a well-known Chinese tongue-twister: 四是四,十是十,十四是十四,四十是四十,四十四隻石獅子是死的; sì shì sì, shí shì shí, shí sì shì shí sì, sì shí shì sì shí, sì shí sì zhī shí shī zì shì sǐ de; '4 is 4', '10 is 10', '14 is 14', '40 is 40', '44 stone lions are dead'.

- In The Dresden Files series by Jim Butcher, the protagonist Harry Dresden comes into possession of a "Tibetan Temple Dog", frequently also referred to as a Foo Dog or Foo Spirit. Named "Mouse", he is depicted as an unusually large mastiff-like dog with human level intelligence, remarkable resilience and strength, as well as the ability to perceive and attack spirits and non-corporeal beings.

- In Richard Russo’s novel Nobody's Fool, Miss Beryl Peoples owns a two-headed "foo dog" she purchased while traveling the Orient. Miss Beryl claims it is called a "foo" dog because the dog says, "Foo on you!" when he is not approving of a person's actions.

- In Roger Zelazny's novel Lord Demon, the protagonist Kai Wren has two Fu dogs as pets - the green male Shiriki and the orange-red female Shambhala.

- The Legendary Pokémon Entei is potentially inspired by a Chinese guardian lion, most famously on Pokémon 3: The Movie – Spell of the Unown: Entei.

- On Dragonheart, Draco's design is partially inspired by a Chinese guardian lion.

- In Gosei Sentai Dairanger, the Green Ranger and associated mecha called Star Shishi are based upon the Chinese guardian lion. When adapted for the second season of the American series Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, the mecha was named the Lion Thunderzord and used by the Black Ranger.

- In Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra, Lion Turtles are giant and wise creatures with the head of a guardian lion and the body of a turtle.

- In the Marvel Cinematic Universe film Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, Chinese guardian lions reside in Ta Lo and act as protectors for its inhabitants. They are capable of harming and destroying the soul-stealing minions of the Dweller-in-Darkness without the use of dragon scales.

See also

- Komainu to compare its use in Japanese culture

- Qilin, another mythical creature in Chinese culture

- Sphinx

- Chinthe similar lion statues in Burma, Laos and Cambodia

- Shisa similar lion statues in the Ryukyu Islands

- Nian to compare with a similar but horned (unicorn) mythical beast

- Pixiu to compare with a similar but winged mythical beast

- Haetae to compare with similar lion-like statues in Korea.

- Foo dog, dog breeds originating in China that resemble "Chinese guardian lions" and hence are also called Lion Dogs.

- Asiatic lions found in nearby India are the ones depicted in the Chinese culture.

- Nghê creatures with similar functions to Chinese guardian lions in Vietnamese culture

- Piraeus Lion

- Tibetan Snow Lion

- Traditional Chinese Lions (Indianapolis Zoo)

- Medici lions

- Lion dance, another use of lion imagery in costume and motion.

- Culture of China

- Chinese mythology

- Chinese dragon

- Door god

References

- ^ "Lion of Fo – Chinese art". britannica.com.

- ^ Laurence E. R. Picken (1984). Music for a Lion Dance of the Song Dynasty. Musica Asiatica: volume 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-521-27837-9.

- ^ Marianne Hulsbosch; Elizabeth Bedford; Martha Chaiklin, eds. (2010). Asian Material Culture. Amsterdam University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9789089640901.

- ^ D. Eastlake, C. Manros, and E. Raymond, RFC 3092: Etymology of "Foo", The Internet Society, April 1, 2001.

- ^ Article Lion of Fo at the Online version of Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "The Sunday Tribune – Spectrum – 'Art and Soul". tribuneindia.com.

- ^ Schafer, Edward H. (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand, a Study of T'ang Exotics. University of California Press.

- ^ 卷四孝和孝殤帝紀第四 [Annals of Emperor Xiaohe; Emperor Xiaoshang]. 後漢書 [Book of the Later Han].

安息國遣使獻師子及條枝大爵

- ^ 狻猊介绍(提问:狻猊怎么读?答案:【suanni】) [Suanni introduction (How to read 狻猊?) Answer: "suanni"]. fantizi5.com.

External links

- Foo Dog in Tattoo Art. Meaning and Design Ideas.

- A blog about the adventures of a Foo Dog statue all over the United States.

- Netsuke: masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains many representations of Chinese guardian lions