Prehistory of Mesopotamia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The prehistory of Mesopotamia is the period between the Paleolithic and the appearance of writing in the area of the Fertile Crescent around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, as well as surrounding areas such as the Zagros foothills, southeastern Anatolia, and northwestern Syria.

In general, Paleolithic Mesopotamia is poorly documented, with the situation worsening in Southern Mesopotamia for periods prior to the 4th millennium B.C. Geological conditions meant that most remains were buried under a thick layer of alluvium or submerged under the waters of the Persian Gulf.

The Middle Paleolithic saw the emergence of a population of hunter-gatherers living in the caves of the Zagros and, on a seasonal basis, on numerous open-air sites. Producers of a Mousterian-type lithic industry, their funerary remains found at Shanidar cave indicate the existence of solidarity and the practice of healing between members of a group.

During the Upper Paleolithic, the Zagros was probably occupied by modern man. The Shanidar cave contains only tools made of bone or antler, typical of a local Aurignacian called "Baradostian" by specialists.

The Final Epipaleolithic period, characterized by the Zarzian (around 17,000-12,000 years BC), saw the appearance of the first temporary villages with round, permanent structures. The appearance of fixed objects such as sandstone or granite millstones and cylindrical basalt pestles indicated the beginning of sedentarization.

Between the 11th and 10th millennia BC, the first villages of sedentary hunter-gatherers are known in Northern Iraq. Houses seemed to be built around the notion of a "hearth", a kind of family "property". Evidence of the preservation of the skulls of the dead and of artistic activities on the theme of birds of prey are also discovered.

Around 10,000 to 7,000 BC, villages expanded in the Zagros and Belikh valleys (Upper Mesopotamia). The economy was mixed (hunting and the beginnings of agriculture). Houses became rectangular and the use of obsidian was noted, testifying to contacts with Anatolia where there were numerous deposits.

The 7th and 6th millennia BC saw the development of so-called "ceramic" cultures. Known as Hassuna, Samarra, and Halaf, they were characterized by the definitive introduction of agriculture and animal husbandry. Houses became more complex, with large communal dwellings around collective granaries. Irrigation was introduced. While the Samarra culture shows signs of social inequality, the Halaf culture seems to be made up of small, disparate communities with little apparent hierarchy.

At the same time, in southern Mesopotamia at the end of the 7th millennium B.C., the Ubaid culture developed, of which Tell el-'Oueili is the oldest known site. Its architecture was highly elaborate, and its inhabitants practiced irrigation, indispensable in a region where agriculture without an artificial water supply was impossible. In its greatest expansion, the Ubaid culture spread peacefully, probably through the acculturation of the Halaf culture, across northern Mesopotamia to southeastern Anatolia and northeastern Syria.

Towards the end of the 4th millennium B.C., villages, apparently not very hierarchical, expanded into towns, society became more complex and an increasingly strong ruling elite was established. The most influential centers of Mesopotamia (Uruk and Tepe Gawra) saw the gradual emergence of writing and the state, traditionally marking the end of prehistory.

Geographical and archaeological setting

Located in the historic region of the Fertile Crescent in the ancient Near East, around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Mesopotamia corresponds for the most part to present-day Iraq, to which is added to the north a fringe of present-day Syria and the southeastern part of Turkey. Within this territory, two regions can be distinguished: Upper Mesopotamia, or Jezirah, and Lower Mesopotamia.[1] Furthermore, the strong cultural similarities observed throughout Mesopotamian prehistory between the regions immediately east of the Tigris and west of the Euphrates allow the study of a larger Mesopotamia bordering the foothills of the Zagros mountains.[2]

Upper Mesopotamia is a hilly and flat region with an average altitude of between 200 and 300 meters, covered by steppe vegetation and extending east of the Tigris and west of the Euphrates. Most of the region enjoys sufficient rainfall for dry farming, but its southern limits are Ramadi on the Euphrates and Samarra on the Tigris. The part of the Jezirah between the tributaries of the Tigris and Euphrates for the Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic periods is virtually undocumented. This can be explained both from an archaeological point of view, given the paucity of surveys carried out in this area, and from a human point of view, as the region may have been virtually unoccupied during the periods concerned.[1]

Today, Lower Mesopotamia consists of a gently sloping alluvial plain (37 meters above sea level in Baghdad).[3] Around 14,000 B.C., the ancient delta of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers was at the level of the Gulf of Oman. Around 10000 BC, only a third of the Persian Gulf's present surface was covered by sea. As a result, many Paleolithic sites can be found beneath the waters of the Gulf. Thus, the flora, fauna, and prehistory of the once-dry delta remain unknown. After the waters of the Gulf had risen, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, carrying and depositing alluvial deposits at the end of their course, caused the sea level to rise again. This last phenomenon buried under several meters of alluvium or under a water table all the remains of sites that may have been established before the 4th millennium BC on a plain then covered by steppes.[4] The only remaining evidence of the steppes of southern Mesopotamia - once an extension of the southern Jezirah steppe - are the plains between the left banks of the Tigris and the foothills of the Zagros. Today's alluvial plains are therefore virtually devoid of any Palaeolithic or Neolithic remains on the surface dating from before the 7th millennium B.C. This is not due to the fact that the sites were unoccupied, but rather to their disappearance under several meters of alluvium, where they remain unexplored if they have not been destroyed by natural forces.[1][5][6][7]

Lower Palaeolithic

Whereas 600,000 years ago, the Archantropians left flint tools all over the Mediterranean (Egypt, Syria, Palestine, Iran), leaving Turkey and the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates, The first traces of man in Mesopotamia appear to be rolled and bifacially-carved pebbles discovered in 1984 near Mosul in Iraq, dating from the Late Acheulean, i.e. from the last quarter of the Lower Paleolithic (between 500,000 and 110,000 years BC).[8]

Middle Paleolithic

Further evidence of human presence was discovered in 1949 at Barda Balka ("Raised Stone" in Kurdish), not far from the town of Chamchamal in Iraqi Kurdistan. A few carved flint artifacts found on the surface around a Neolithic megalith prompted a deeper survey in 1950. At a depth of 2 meters beneath fluvial sediments, a workshop or camp of some kind was discovered, occupied repeatedly over a short period by hunter-gatherers. Their tools consisted of biface-cut flints, axes, scrapers, and pebbles in the form of cleavers, suggesting stone working and butchery. This work was carried out near a spring on the banks of a stream. Based on typological and geological criteria, it is estimated that the site dates back to 80,000 BP (years before present). This date seems to be confirmed by the discovery, around the tools, of animal bones such as Asian elephants and rhinoceros, animals that disappeared from these regions some time later.[9][10]

At the beginning of the Würm Ice Age, prehistorians believed that people lived in caves on a seasonal basis. In 1928, British archaeologist Dorothy Garrod discovered a Mousterian lithic industry in the lower layers of the Hazar Merd cave in Iraqi Kurdistan, which is also found in many open-air sites.[10]

Meanwhile, in Iraqi Kurdistan, the Shanidar cave on the southern flank of Jebel Baradost in the foothills of the northern Zagros, in the province of Erbil in north-eastern Iraq, represents the most important archaeological site in the discovery of Middle and Upper Palaeolithic Mesopotamia. Between 1951 and 1960, the team led by American archaeologist Ralph Stefan Solecki excavated the cave floor and reached virgin rock at a depth of 14 meters.[11] They uncovered four different cultural levels. The deepest and thickest of these (8.5 meters), Level D, attributed to the Middle Paleolithic, reveals layers of ash, mingled with flint tools and bones, suggesting that the cave has been intermittently occupied since 60,000 BP, for some ten thousand years. Numerous tools such as points, scrapers, chisels, and drills characteristic of the Mousterian lithic industry were also found. Arrowheads discovered in the upper layers of Level D, type "Emirati" and similar to those found in Palestine, suggest contacts with the Mediterranean Levant.[12] In addition, the pollens discovered and analyzed in the laboratory enable researchers to deduce strong climatic changes during the period of the cave's occupation: first warmer than today, then very cold, and finally hot and dry up to 44,000 years BP.[13]

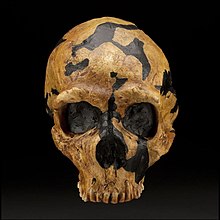

But the greatest discovery was the presence of ten human skeletons, including two infants. These skeletons, most of them badly damaged, have been there since 60,000 BP for the oldest and 45,000 BP for the most recent. The skulls are in relatively good condition, with Neanderthal characteristics.[14][15] The ten skeletons are divided into two categories, 10,000 years apart: on the one hand, a large proportion belonged to men, women, and children living in the cave, who died as a result of falling rocks from the cave ceiling; and on the other, bodies obviously placed there for burial between 50,000 and 45,000 years BC. One of the deposited dead appears to have been lying in a fetal position and covered with flowers; another, discovered in 2017 not far from the first, is placed in a resting position.[16]

In addition to the observation of possible funerary practice, these discoveries provide a better understanding of some Neanderthal behaviors. One of the skeletons shows so many traces of severe handicaps (including deafness and probable blindness) and serious injuries that its dependence on others seems obvious right up until its death at the advanced age of approximately forty. This suggests solidarity and the use of care between members of a group.[17][18][19] Conversely, another skeleton showing traces of rib injuries suggests the existence of interpersonal violence within the same group.[20]

As far as the lower regions are concerned, briefly excavated sites indicate that the desert south of the Euphrates and the regions bordering this river, or at least an earlier (fossil) system whose course was then quite different from that of the present day, were traversed by bands at this period. But if there are campsites from this period in the plain, they are buried under river sediments.[21][22]

Upper Palaeolithic

Level C of the Shanidar cave (between 34,000 and 26,500 BP) contains no skeletons indicative of occupation during the Upper Palaeolithic (between 45,000 and 12,000 BP). Only objects made of bone or antler have been found. However, their Aurignacian-like style was original enough for the American archaeologist Ralph Stefan Solecki, in 1963, to call them Baradostian (an allusion to the Baradost mountains where the cave is located). During the last glacial maximum of the Würm glaciation, which reached its coldest point around 20,000 BP, the Shanidar cave seems to have been deserted for around 10,000 years, perhaps because the cold forced the inhabitants down into the surrounding valleys, or because of the threat of boulders falling from the ceiling of the cave.[23]

The style of the stone tools, whose bases are Mousterian and already present in the upper layers of Shanidar Level D, appears to have become more refined: light and often pointed armatures indicate a renewed use of mechanically propelled weapons, such as the bow. This was a major feature of the lithic industry in the Upper Palaeolithic of the Zagros. Moreover, despite the paucity of test pits, the pendants were numerous and mostly made from the atrophied canines of red deer, drilled into the flat of the root, or from perforated marine shells colored red, or fashioned from hematite. One of these imitates the silhouette of a deer's canine tooth, polished, shiny, and embellished with a series of peripheral notches. These aesthetic activities tend to reinforce the idea that a spiritual "revolution" accompanied the progression of cutting techniques.[24]

Other sites from this period have been discovered and excavated, stretching across the width of the Zagros to the foot of the Himalayas. The Yafteh cave in Lorestan is one of the most important.[25][26] These sites all feature Aurignacian tooling for the corresponding and higher time strata. Thus, in 2006, the term "Baradostian" was revised to define an earlier stage of the Aurignacian, intermediate between the Mousterian and an Aurignacian specific to the Zagros.[27][28] In the eyes of researcher Marcel Otte, all the Aurignacian material from the Zagros seems to adopt a continuity, both technical and aesthetic, from east to west, to such an extent that a migratory tendency of the Zagros Aurignacian is confirmed from Central Asia to Southeast Europe, with the caves of the eastern foothills of the Zagros as an intermediary.[29]

Moreover, even if we can assume that the Baradostian population was made up of humans whose anatomy is that of modern man,[23] there are very few paleoanthropological documents to support this: one molar from the Eshkaft-e Gavi cave (southern Zagros) and one premolar from the Wezmeh cave. What's more, the chronology of these two witnesses has not been precisely determined.[30]

Epipaleolithic

At the beginning of the Epipaleolithic period (around 17,000-12,000 BP), during the last Ice Age, the northern regions of the Zagros, at medium and high altitudes, were deserted. The return of human presence was not felt until the climatic warming that followed the last glacial maximum,[31] in parallel with the Epipaleolithic facies known in the Levant and on the southern coast of Anatolia.[32]

Zarzian

The end of the Epipaleolithic was marked by the Zarzian culture, which covered Iraqi Kurdistan with the Zarzi, Palegawra, and Shanidar B1 caves (reoccupied) then B2 (again uninhabited, but containing several burials), as well as the Zawi Chemi site. The latter is a "village" located 4 kilometers downstream from Shadinar Cave on the Great Zab River, and has been dated to the cave's B2 level (10,870 BP).[33] The Zarzi cave, eponymous with the Zarzian culture, was discovered and excavated in the 1920s and 1930s by archaeologist Dorothy Garrod. Her discoveries were instrumental in defining the characteristics of the Zarzi culture, alongside those of the Natufian and Kebarian cultures of the Levant, also discovered in the 1930s.[34] At the time, while the Zagros was all but abandoned by archaeologists, the Levant and the Natoufian culture were the focus of more detailed excavations. Despite this, during the 1960s, other Zarzian sites were discovered - notably Warwasi, Pa Sangar, Ghar-i Khar - as well as a set of thirty-five bodies deposited in the Shadinar cave around 10,700 BP,[35] providing a better description of Zarzian culture. Further research, carried out from the 1980s onwards, shed light on elements such as climate, vegetation, and human activities. In 2006 and 2017, carbon-14 dating of animal bones found at several sites, such as Palegawra, enabled the refinement of various dates.[36][37]

Carbon-14 dating at Shanidar and Palegawra indicates that the Zarzian presence began around 12,000 BP[nb 1] and probably ended with the advent of the Neolithic around 10,000 years ago.[23][38] During this period, climatic conditions improved sufficiently to allow vegetation to spread to higher altitudes.[39] The Western Zagros, populated by deer and goats, seems to be covered by a dense wooded steppe, while the Palegawra documentation indicates the presence of oaks, poplars and even junipers or tamarisk. The banks of the Middle Euphrates and probably the Tigris are bordered by riparian forests of poplar, willow, and tamarisk. However, there is a certain discrepancy between pollen data and paleozoological data, especially in the Zagros region, where forest animal species sometimes appear where pollen diagrams indicate the existence of steppes.[37][40]

Object manufacturing

The reduction in tool size that began at the beginning of the Baradztian reached its peak during the Zarzian, with a variety of microlithic tools, notably in geometric shapes, including many triangles, trapezoids, and curved pieces at the end of the Zarzian. Polished axes have also been found at Palegawra and Zawi Chemi, but do not seem to belong to the Zarzian culture. The only polished axe that seems to belong to this culture comes from Deir Hajla in the Jezirah. In terms of heavy tools, various Late Zarzian sites, including Zawi Chemi, yield sandstone or granite millstones with cylindrical basalt pestles. Although some of these heavy tools can be transported - such as the 30-centimeter sandstone slabs found at Zawi Chemi - some appear to be embedded in the ground. Personal ornaments made from bones are also known. Some are made from marine shells, indicating the existence of a long-distance trade or travel network. Beads and pendants have also been discovered at Palegawra and Pa Sangar.[41][42][43]

Habitat

The main characteristic of the Zagros occupants during the first part of the Zarzian period was movement. They traveled in bands from one place of sustenance to another. Places of occupation include small sites, such as hunting shelters with no permanent construction, where small bands hunt, prepared, and brought back the prey to fixed base camps. Other sites appear to be less frequently occupied transitional camps where stone tools were made or repaired. Base camps, on the other hand, were set up under rock shelters or in larger caves such as Shanidar, Palegawra, or Pa Shangar. What these shelters seem to have in common is that they lied at the crossroads of a variety of environmental environments, and offer a wide vantage point over the entire plain from which to observe the movements of prey (gazelles and onagers).[37][42][44][45]

Alimentation

At sites such as Pa Sangar, Palegawra, Zarzi, and Shanidar, archaeologists note that hunting practices remained unchanged from previous periods: goats and onagers were still the main source of meat. However, the range of species hunted expanded considerably compared with earlier periods: an increase in small prey such as partridge, duck, freshwater crab, clams, turtles, and, for the first time, fish. The debris from Zarzi and Shanidar also contains land snail shells. This diversity seems to be due to dietary stress, forcing hunter-gatherers to collect smaller animals, as larger animals were less available due to environmental changes. The Palegawra site also indicated the appearance of domestic dogs.[37][41]

The Late Zarzian or Proto-Neolithic period

Zawi Chemi

During the Late Zarzian, the Zawi Chemi site seems to indicate a trend towards sedentarization. Situated in an open valley not far from the Great Zab River, a few kilometers from the Shanidar cave, the site is made up of separate dwellings of approximately circular or semicircular shape, all or part of which are dug into the ground. With a stone foundation, they sometimes feature a light superstructure of stone or wood, topped by an organic roof.[46][47] At Zawi Chemi, there is also an enigmatic circular construction measuring 2-3 metres in height, near which there is a deposit of fifteen wild goat skulls and seventeen wings from birds of prey.[48] This installation leads to the hypothesis of the ritual use of raptor wings or feathers to adorn clothing or headdresses,[49] and reminds researcher Joan Oates of the avian frescoes at Çatal Höyük.[50] However, although the site shows a clear trend towards sedentarization, it seems to have been occupied only during the spring and summer periods, the winter dwelling place being as yet unknown.[47]

The Shanidar tombs

Shanidar B2 - the most recent level (c. 10,750-10,000 BP) - is contemporary with the Zawi Chemi settlement. It shows no signs of human occupation, but features a semicircular stone construction and, above all, numerous burials, many of which have been identified as those of children or adolescents.[51] All the burials in the cave have probably not yet been unearthed, as the excavation zone only covers an area of 6 x 6 meters at the bottom of the cave. So there could still be other unexplored graves.[52] Twenty-six graves containing the remains of at least 35 people have been identified. The bodies are folded in an unnatural way and sometimes piled up in both individual and collective graves.[53] Some of the graves are surrounded by stones, and the bodies bear no traces of specific mortuary practices. However, 15 tombs were provided with funerary objects. These offerings most commonly consist of beaded decorations, often made from colored stones and sometimes shells or crab claws. The most lavishly endowed tombs are the children's tombs: one of them contains over 1,500 stone beads.[54]

The reasons for choosing the Shanidar cave as the site for the cemetery are still unknown. Perhaps the cave was recognized at the time by the inhabitants of the Shadinar valley as a place formerly occupied by distant ancestors, or perhaps it was felt to be an effective shelter against animals or bad weather. Whatever the case, the cemetery was not used for very long, and the bodies piled there - some skeletons damaged by the placement of new bodies - are very contemporary with one another.[55] While Zarzian society seems rather organized in small groups of twenty or so individuals under a more or less informal authority, but with an egalitarian structure, the discovery of gifts deposited near certain Shanidar bodies to the detriment of others suggests, at the end of the Zarzien, the emergence of an unequal social organization between individuals.[47]

First Mesopotamian villages

The seasonal villages of Zawi Chemi and Shanidar B1 seem to have given way to the first known sedentary villages in Northern Iraq: M'lefaat, Qermez Dere and Nemrik. These are located at the junction of the Zagros foothills and the Upper Mesopotamian steppe. Most of them were established between the 12th and 10th millennia B.C. In many ways, they are considered to be the heirs of the Zarzian, but their evolution is only felt from the 9th millennium B.C. onwards, on the bangs of the other cultures affiliated to the PPNA and PPNB, whose influence they only come to know from the 8th millennium B.C. onwards.[56]

However, population density was probably very low in northern Mesopotamia, and no sites have been recorded in the Jezirah plains. This in no way implied human absence: nomadic or more mobile communities might still have used part of the region on a seasonal basis. From an archaeological point of view, this is difficult to demonstrate.[57]

Hunting and gathering

The inhabitants of these villages still hunt and gather, and there is no trace of agricultural or livestock activity during this sequence. Gazelles, hares, foxes, a few oxen, equines, and ovicaprinae are the hunters' preferred game, while gatherers harvest wheat, barley, lentils, peas, and vetches, all part of the local wild environment. These plants show no trace of domestication, and there is no evidence of a predominance of cereals.[56]

Nemrik, being closer to the mountains, which are less well supplied with plant foods than the plains, seems to have an economic base more closely linked to hunting. Numerous bolases, accompanied by the remains of hunted animals that may simply have been shot by their hunters, suggest that, in the 7th millennium BC, young animals may have been captured for breeding purposes and also opened up the possibility of falconry, as much earlier at Zawi Chemi.[58]

Family residences

The occupants of the villages of M'lefaat, Qermez Dere and Nemrik had been sedentary hunter-gatherers since the 11th millennium B.C. and, in terms of housing, perfected the skills of their Natoufian predecessors from the Levant: at Nemrik, the houses buried in a round pit included, in addition to wooden posts, two to four thick inner pillars. These vertically-erect stone pillars, sometimes fashioned after an anthropomorphic model, support a terraced earth roof, some with ladders for roof access. These pillars are wrapped in a layer of clay and lime. Lime seems to have been used here earlier than in the Levant. In Nemrik and Qermez Dere, the floors are also repeatedly covered with lime.[59] This continuous renovation and cleaning of individual houses suggests a significant social change: the transformation of the shelter into a notion of "home", a place of permanent residence for which a kind of family "property" could develop.[58]

Initially, houses were simply dug into the ground and measured between four and six meters wide. By the 9th millennium B.C., they had expanded to a radius of between six and eight metres. In addition, at M'lefaat and Qermez Dere, villages were equipped with an open central area paved with pebbles. Designed for common household tasks, researchers have discovered millstones and fireplaces.[59][60] Later, around the houses, the first low, above-ground walls of stone and/or earth were built around the original pit, and towards the end of the millennium, the first bricks appeared in Nemrik and M'lefaat. They replaced the stacked, dried earth of the low walls. They are made from a mixture of clay, water and a vegetable degreaser such as grain husk or chopped straw. The bricks are shaped in various ways (into wafers or cigars) and sun-dried - this is considered a characteristic of early Neolithic sites in northern and central Mesopotamia.[60] They are cemented with a clay mortar. This prefabricated element technique avoids the drying time previously required between each layer of stacked earth.[61][62]

Lithic materials

Also ahead of the Natoufian of the Levant, the lithic industry, very homogeneous in the region and based on local raw materials,[63] is marked by the laminar cutting of flint by pressure and by stone polishing. However, transformations in this industry seem to have been more discreet over the first two millennia of its existence.[64] At Nemrik, excavators found heavy objects such as millstones, grinders, mortars and pestles, grinding and polishing stones. Lighter objects include stone balls (bolases), plates, mace heads, pointed objects, and polished axes (including miniature specimens). Rarer stone vessels have also been discovered, one of which is made of marble.[63]

Around 9500 B.C., M'lefaat, although far removed from the Khiamian context, seems to be under Syrian influence, as El Khiam points are used.[58][59] However, in the final phase of this industry - which Jacques Cauvin calls "Nemrikian" - more original diamond-shaped arrowheads appear: the "Nemrik points".[59] From this period, archaeologists at M'leffat have found bone punches, beveled edges, and the oldest known collection of tokens.[58]

Art and rituals

Symbolic representations of birds of prey are found in polished stone, especially at Nemrik,[65] carved at the end of stone rods (probably pestles).[66] These raptors refer to the Zawi Chemi bone deposit discovered in 1960 and studied by Rose Solecki. They bear witness to an original local cult and could support the hypothesis of the use of falconry.[58] The skeleton of an individual was discovered in a burnt-out house, his arms apparently outstretched towards one of these bird heads.[67] Other animals are modeled in clay, carved or engraved on stone vases: wild boars, snakes, lions, and foxes at Hallan Çemi in southeastern Anatolia. Figurines of human beings were also fashioned. The wild ox, though occasionally hunted, is nowhere to be seen except[68] at Hallan Çemi: one house contains the skull and horns of a wild auroch, which were at one time hung on the wall.[69] The subjects are similar to those of objects from Mureybet in Syria and Cafer Höyük in Turkey. At Nemrik, other objects, such as stone pendants of various shapes, malachite beads, stone representations of sexual organs, and river shell ornaments, were discovered.[70]

At Qermez Dere, archaeologists notice one or two pairs of clay pillars whose function does not appear to be to support the roofs of houses. These stelae could have a symbolic meaning, suggesting that both ritual and domestic activities took place in the houses.[69]

Qermez Dere and Nemrik reveal some evidence of rituals: notably the deliberate preservation of human skulls which, in the final period of both villages, are carried into each house. This indicates ancestor veneration and early recognition of the house as a "family home", confirming the sedentary nature of the region's inhabitants and underlining the solidarity between members of the same family. A cemetery dating from the last phase of occupation at Nemrik features funerary objects, but also, in some of the bodies, flint projectile points embedded in the bones - clear evidence of violent deaths.[60]

The beginnings of agriculture

Around 7500 BC, the Neolithic movement continued with the arrival of the first agricultural hunters, who organized themselves into villages in the high valleys of the Tigris and the Zagros. These Neolithic aceramic villages, whose economy was based on both hunting and agriculture, were larger in size, accommodated more people for longer periods of time, and their architecture was more substantial. However, agriculture appeared only very gradually: the first traces of domesticated plants were only discovered towards the end of the PPNB (early 7th millennium BC). Prior to this, the inhabitants of these villages intensively harvested wild plants with sickles, equipped themselves to crush the seeds and place them in containers. In addition, certain animals, notably goats, were domesticated at most sites.[58][68][71][72]

Despite an established network of goods exchanges between the Tigris valleys, the Zagros, and even Anatolia (the use of obsidian is one of the main indicators of this), it seems that the Zagros populations followed an evolution independent of that of the first farmers in Turkey, to the north, or those to the west, of the Fertile Crescent: their lithic industry seems to be heir to that of the M'lefaat and Nemrik villages of the preceding era.[73] However, there are two points in common between all the sites of the period: the mixed economy, and the fact that houses became rectangular.[58][68][74]

In the Zagros, which seems to be a Neolithic center in its own right, the appearance of agriculture is illustrated by the sites of Bestansur and Chogha Golan. The main witness to the occupation of the Tigris Valley is the site of Tell Maghzaliyah, the remains of a village located not far from Qermez Dere and related to those of the Balikh Valley.[74][75]

It was also at the Tell Maghzaliyah and Seker al-Aheimar sites (of the same cultural type originating from the Taurus Mountains, located in the Khabur Valley), that the first decorated pottery dating from the end of the 8th millennium BC was discovered, thus creating a link between the final PPNB and the beginning of the so-called "Proto-Hassuna" period.[58][76]

Southern Mesopotamia

During the 8th and 7th millennia B.C., the landscape of southern Mesopotamia seems to have been an assemblage of constantly fluctuating marshlands alongside more arid areas, the whole presenting a landscape generally comparable to that in which today's Marsh Arabs live. It is possible that many of the remains of this period, located near rivers (which were major settlement sites), are still present today, but inaccessible because they are buried under the alluvial deposits of the Tigris, Euphrates and their numerous tributaries and wadis, when they have not simply been eroded by them. Some of them are also located beneath the remains of historic eras that are currently being explored. Some sites, such as Hadji Muhammed and Ras al Amiya, were discovered accidentally during modern construction work.[77]

In the desert areas to the west of the vast wadi systems, now drained and dry, archaeologists have uncovered evidence of flint industries similar to those of the late Levant, for which it is possible to draw parallels with the flint industries of northern Arabia. These industries are perhaps characteristic of the Gulf area, which was still dry at the time - and undoubtedly influenced by a monsoon climate.[78] In addition, "Mesolithic" lithic tools (with microliths, burins, scrapers), roughly dating from periods prior to the Neolithic, have been found during surface surveys in the Burgan hills of Kuwait.[79] But as far as the first prehistoric populations to the west and south of the future Sumer are concerned, researchers can only speculate.[80]

A home in the Zagros

Excavated between 2012 and 2017, the Bestansur site is located in the foothills of the Zagros on the edge of the Shahrizor plain, 30 kilometers southeast of the town of Sulaymaniyah. Geographically close, but predating Jarmo, the village survived between 8000 BC and 7100 BC. Inhabitants enjoy a wide range of ecological opportunities including fertile arable land, water sources, hilly and mountainous terrain suitable for hunting a diverse range of animals and harvesting a variety of plants, not to mention the proximity of multiple stone deposits suitable for the manufacture of polished and carved stone tools.[74]

Bestansur's architecture was characterized by rectilinear, multi-room mud-brick buildings. Not all of these buildings appear to have been used for habitation: one was entirely devoted to burying the dead. Often dismembered, the bodies were probably exhumed and certain parts, notably skulls, were removed for reburial in the dwellings. This "house of the dead" provides a wealth of information about the difficulties faced by the inhabitants, probably linked to the Neolithic transition: numerous skeletons of children and young people highlight serious problems of malnutrition and dietary stress in early life.[74]

Nevertheless, this dietary stress occurred despite a high level of biodiversity, which should have reduced dependence on a set of Neolithic plants and thus limited the risks associated with early agriculture and the early exploitation of animals such as domestic goats, sheep, and pigs. Here, too, a form of hunting of small and large mammals persisted, as did the consumption of fish, poultry, and land snails, important components of the diet.[74]

Chogha Golan is one of the oldest known Neolithic sites in Iran. Excavated in 2009 and 2010, it covers an area of around 3 hectares, and 11 levels of occupation from the Ceramic Neolithic (between 12,000 and 9,800 BP calibrated) have been attributed to the site. The site's occupation has left abundant and diverse archaeological remains: traces of plastered walls, lithic industry, stone crockery, engraved bone objects and clay figurines. Animal remains are very varied: goats, wild boar, gazelles, wild donkeys, cattle, hares, rodents, birds and fish, etc.[75]

The abundant botanical remains document the beginnings of agriculture and show that it only appeared over a very long period. Here, as at Bestansur, at the time of occupation, the site's surroundings contained wild variants of several of the founding plants of the Neolithic: barley, wheat, lentils and peas. Here too, various studies of the evolution of domesticated plants indicate that the Zagros was one of the hotbeds of plant domestication, along with the northern and southern Levant at the time.[75]

Tell Maghzaliyah and the Belikh Valley

The settlement of the Tigris valleys is mainly documented by the site of Tell Maghzaliyah, the remains of a village dating from the end of the 8th millennium B.C. located not far from Qermez Dere, on a wadi at the edge of the Jebel Sinjar range of hills, whose cultural filiation brings it closer to the cultures that characterize the final PPNB of the northern Levant and the Belikh valley, in northern Syria, where some twenty-four sites, including Tell Sabi Abyad, have been discovered. The occupants of these villages belonged to the typical PPNB cultural facies of Cafer Höyük or Çayönü, and originated in the Taurus Mountains and other regions of Anatolia. Their economy is based on both hunting and agriculture, a well-established feature of the entire Belikh valley, where wheat and barley are grown and sheep and goats raised.[58][68]

Unlike the ancient round houses of Qermez Dere and Nemrik, built around a common area, the Tell Maghzaliyah buildings, clearly all intended for habitation, are rectangular, with adobe walls built on a foundation of limestone slabs and filled with stones. There are both storage and kitchen-living areas and, in one of the houses, there is a chimney with an external flue, similar to later houses in Umm Dabaghiyah and Çatal Höyük. As with Nemrik, the final phases of the village show a wall flanked by towers surrounding the houses, indicating possible conflicts with neighbors.[58]

Like Nemrik, the early Tell Maghzaliyah levels show that obsidian predominates, despite the remoteness of the nearest deposits in Anatolia, from where the pressure-cutting technique was imported. The site also contains projectile points, both leaf-shaped and knives, as well as clockwise-rotating drill bits. In the upper levels of a Belikh Valley site, Tell Sabi Abyad II, Byblos, and Amuq points were found. Flint scrapers, later used during the Hassuna period, are already present. Also discovered in Tell Maghzaliyah and other villages in the Belikh Valley are bitumen-coated sickles, whose blades contain traces of cereal harvests. Inhabitants have also left behind marble bowls, bracelets, and polished punches. Although the village of Tell Maghzaliyah is still aceramic, plaster tableware and decorated pottery are also used. These can be found throughout Jezirah and the Syrian desert, notably at Seker al-Aheimar.[58][68]

Seker al-Aheimar and the "Pre-Proto-Hassuna" period

Seker al-Aheimar is a large Mesopotamian site covering around 4 hectares, and is the only one to provide information about the transition from PPNB to Proto-Hassuna pottery. The acetate levels of the PPNB village feature small rectangular buildings on a paved platform of a type already encountered at Tell Maghzaliyah. The use of lime plaster on brick walls was common. While some aspects of the utilitarian lithic industry at Seker al-Aheimar are similar to that of the Zagros, the end scrapers, burins, polished axes and arrowhead types common at the end of the PPNB are similar to those found in the Belikh Valley. Decorative objects include gypsum vessels as well as stone and Anatolian obsidian beads.[81]

However, the most significant discovery is that of numerous stone vessels, white crockery, and, above all, an early type of watertight vessel that constitutes the oldest form of ceramic found in the whole of North and Central Mesopotamia. Fired on a low, temperate fire, which is characteristic of the first ceramic Neolithic, this ceramic has a dense, granular consistency and is very different from future "Proto-Hassuna" ceramics.[81][82] For researchers Yoshihiro Nishiaki and Marie Le Mière, this discovery demonstrates the existence of an early ceramic phase - represented by a cultural entity provisionally referred to as "Pre-Proto-Hassuna" - which appears to have begun in the Middle PPNB and ended in the Proto-Hassuna, introducing the latter.[82]

The rise of farming communities

The Ceramic Neolithic period (c. 7,000 to 5,000 BC) saw farming communities increasingly occupying Mesopotamian space. Villages were established in the drier climate of Lower Mesopotamia, indicating the development of irrigation systems. This does not mean, however, that Lower Mesopotamia was unoccupied before the 7th millennium BC. Remains of earlier settlements may be difficult to access because they are buried in deep layers of silt or simply destroyed by intense river erosion on the plains.[83] The most important settlements in central Mesopotamia are Bouqras, near the Euphrates, not far from the Iraqi border in eastern Syria, Tell es-Sawwan, south of Samarra on the Tigris, the sites of Umm Dabaghiyah in the steppe west of Hatra and Choga Mami at the eastern end of the Mesopotamian plain, at the foot of the Zagros mountains east of Baghdad.[83][84]

At the beginning of this period (up to 6500 BC), the first decorated ceramics appeared, notably at Bouqras, Tell es-Sawwan and Umm Dabaghiyah. These were perfected until the beginning of the Chalcolithic period. Historians distinguish several cultures in relation to these painted ceramics: those of Hassuna, Samarra, Halaf and Ubaid, the names of the archaeological sites where they were first discovered. In the early centuries, ceramics were first partially decorated with the line incisions, wavy patterns or raised lozenges characteristic of the Hassuna culture. They then become finer and finer, and are entirely covered with geometrical paintings, becoming more complex with representations of stylized natural elements such as plants or birds for the Samarra and Halaf cultures. Even if the production of painted ceramics disappeared at the same time as the use of the first pictographic signs, these decorations cannot be considered as a means of transmitting speech as writing is. However, they are probably a code or pictorial language whose meaning has been lost.[84][85]

In the Zagros, communities seem to have diverged somewhat from those in the Mesopotamian lowlands. Jarmo is a case in point. It's a village located on the western outskirts of the Zagros, on a hill in the Chemchemal valley in north-eastern Iraq. It was originally excavated in the 1940s and 1950s by archaeologist Robert John Braidwood to investigate the origins of agriculture. The village consists of mud-brick houses with several rooms connected by low doorways. Foundations of a type also known at Çayönü in the form of grids were identified. The large number of clay figurines found at Jarmo is probably indicative of a local specialty: over 5,500 figurines and some 5,000 clay tokens have been found there. However, the low-fired "tadpole" pottery proved to be quite distinct from that of the Proto-Hassuna culture found on sites in the Mesopotamian lowlands, while other examples of this pottery are found more to the east. This would seem to indicate, from this period onwards, a cultural demarcation between the Zagros and the Mesopotamian lowlands.[86]

In Upper Mesopotamia, the treatment of the dead prior to the expansion of the Ubaid culture in the 5th millennium B.C. varied in manner and location. These ranged from simple burials accompanied by a few objects to disarticulated bodies whose skulls were given special treatment, such as burial in a ceramic urn. Moreover, although the evidence is weak, it would seem that some communities practiced burial outside the village: burials were found on the summit of the Yarim Tepe mound (a village abandoned when the dead were deposited). At Tell Sabi Abyad, a village that was deliberately burnt down, archaeologists found two skeletons that appeared to be lying on the roof of a house; this was undoubtedly an elaborate ritual in which the dead played a central role. At Domuztepe in southeastern Anatolia, the Death Pit is a mortuary complex containing the intentionally fragmented remains of at least forty individuals. Researchers see in it a transformation of the dead into a reconstituted collective ancestor. Cannibalism and human sacrifice are also possible.[87]

Around 6500 B.C., the use of copper, the appearance of seals, irrigation, wall paintings, the first sanctuaries,[83] increasingly obvious social divisions, and increasingly complex management of society were noted.[80] In addition, the first rectangular molded bricks and the first buttresses inside and outside walls, previously observed at Cafer Höyük, appear mainly at Samarra, Bouqras, and to a lesser extent at Tell-Hassuna.[88]

The Proto-Hassuna phase

Umm Dabaghiyah, occupied for three or four centuries, located in the Iraqi Jezireh between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, clearly better watered in the 7th millennium BC than today, provides the most complete documentation of the Proto-Hasuna phase (c. 7000 BC - 6500 BC). The population of Umm Dabaghiyah, undoubtedly heir to the Syrian PPNB, still operated a mixed economy, with evening primrose hunted predominantly for both its skin and its meat. This may be a seasonal site. Wheat, lentils, and barley were present, however, as well as typical marsh plants, leading us to suspect the presence of nearby salt marshes and shallow lakes in the area. Wall paintings suggest that the fast-moving onagers were trapped in nets.[84][85]

The buildings at Umm Dabaghiyah show indentations in the walls that suggest they were accessed via the roofs. These buildings, with their generally very small rooms, feature internal plaster fireplaces associated with external ovens, suggesting cold winters (as was the case in modern times in the region), unless this device was used for drying evening primrose skins. Some of the buildings, built in long rows, appear to have been reserved for storage. Similar but shorter storage structures were found further north, at Yarim Tepe.[89][90]

Compared with other sites, Umm Dabaghiyah does not have many examples of pottery. Moreover, very similar to the Bouqras pottery that seems to be related to it, it is simple: large jars or bowls painted in red ochre and sometimes decorated with rudimentary motifs such as bands, chevrons or dots. Nevertheless, Bouqras is a much larger village with clear origins in the Syrian PPNB. In addition to the typical Neolithic acetate material and ceramics previously described for Umm Dabaghiyah, finds include alabaster pots and paintings of ostriches or cranes painted in red ochre on some interior walls, all covered with plaster. These buildings with three or four rows of rooms are regular in plan and arranged along narrow streets in a coherent layout. Although there is as yet no clear evidence of this, the size of some of the buildings and this layout suggest the establishment of a formal authority.[91]

Pottery made using a technique similar to that of Umm Dabaghiyah and Bouqras, but differing in style, is also found, albeit more rarely, in Levels I and II of the Tell es-Sawwan site.[nb 2] Sawwan is a 7th millennium BC village in Lower Mesopotamia along the Tigris River, some 80 km north of Baghdad. Some 400 tombs have been discovered here, three-quarters of them containing infants. Some bones are missing from many of the burials. One, for example, contains only the bones of a child's hand, suggesting that some bodies may have been moved to other burial sites. Beneath the tombs lies an enormous quantity of alabaster objects: vases, figurines and miscellaneous objects. All these objects are specific to the Tell es-Sawwan site: some figurines feature inlays of other materials, such as shells or stones of different colors, frequently highlighting the eyes. Depending on how they are arranged in relation to the tombs, researchers have deduced significant social differentiation between individuals. A few clay and alabaster figurines discovered outside the graves may have been associated with funerary rituals. The majority of burials were found under large, three-part buildings (known as "tripartite"), a structure that lasted well into Mesopotamian antiquity. But some burials are located in other sectors and are clearly dissociated from any architecture, making it difficult to make a clear-cut interpretation between "tombs under housing" and "cemetery".[91][92]

The houses here are "tripartite", i.e. they are composed of a central rectangular space through which one enters by one of its widths, giving access to a series of small rooms that border it symmetrically along its lengths.[93] At Tell es-Sawwan, these buildings are found empty and contain no household items, as if the inhabitants had left, taking everything with them. In fact, the site was probably deserted and reoccupied after an estimated period of between 123 and 300 years.[91][94]

The end of the Proto-Hassuna period also marked the first use of seals: at Hassuna, Bouqras and Sawwan, they introduced a practice that developed in Mesopotamia and still persists today as a "guarantee". The first seal impressions appear on small white lids, clearly identifying the "property" contained in the sealed container. By the end of the Samarra period, these seals were widely used as "contractual" devices in central and northern Mesopotamia.[95]

The Hassuna culture

The Hassuna culture (c. 6500 BC - 6000 BC) takes its name from an archaeological site, Tell Hassuna, located in central Jezirah, between the Tigris valley and Jebel Sinjar, not far from present-day Mosul. Yarim Tepe and Tulul eth-Thalathat, on the Jezirah plateau and the Kurdistan foothills, also belong to the Hassuna profile. These villages survived throughout the 7th millennium BC in a rainy region where dry crops were possible. The inhabitants grow a wide variety of cereals, lentils and peas. Beef, goats, sheep and pigs are raised here, but aurochs, gazelles and bears are also hunted.[96]

Initially built of adobe, the walls of multi-room houses were gradually built of shaped bricks. The houses were also laid out more closely together and became increasingly complex, with one house comprising eleven rooms. Already in use in the North Mesopotamian Neolithic society of Tell Maghzaliyah, the system of families grouped around collective granaries considered to be the center of the habitat reached its full development during the Hassuna period. This system seems to have ensured community cohesion.[96]

The Hassuna culture is characterized by very distinctive pottery, with motifs painted in red ochre or incised in parallel line networks and/or chevrons. This type of pottery is largely found in northern and central Mesopotamia, as well as in the Khabur region of northeastern Syria.[85]

It is produced by firing in large kilns. At Yarim Tepe, archaeologists have discovered the first well-preserved example of a potter's kiln consisting of two superimposed chambers separated by a wall with a fume evacuation system.[96]

The Samarra culture

The Samarra culture (c. 6200 BC - 5700 BC) is characterized by fine-painted ceramics. Documented by Tell es-Sawwan and Choga Mami in central Mesopotamia, it is considered an evolution of Hassuna-period ceramics and those of the Levant Corridor, whose villages were gradually depopulated.[97] Archaeologists have also found evidence of Samarra ceramics at a number of sites in northern Mesopotamia, as far afield as the Syrian Jezirah and the Belikh Valley. Samarra pottery was easily recognizable and often elaborately decorated.[98] Better made than its predecessors, it consists of large dishes and vases with rounded shoulders. Its light beige, slightly rough material is more harmonious. The decoration is made up of geometric designs painted in bright red, brown, or violet-brown. These motifs can also represent men, women, birds, fish, antelopes, or scorpions.[84][99] On some collars, there are even reliefs of human faces whose features are painted in a stylized manner. Pottery characteristic of this culture was also found at Tell el-Oueili, the oldest known village in southern Lower Mesopotamia, which documents the Ubaid period (Ubaid 0 phase, c. 6200 BC - 5900 BC).[84][95]

-

Painted dish from the Samarra period. Pergamonmuseum, Berlin.

-

Painted dish from the Samarra period. Pergamonmuseum, Berlin.

-

Jar with painted decoration from the Samarra culture, Samarra. British Museum, London.

-

Alabaster vase and necklaces from Tell es-Sawwan, c. -6000 - -5800 National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad.

Samaritan statuettes were made in terracotta or alabaster. The figures are generally standing or crouching, and most often female.[100] None of the figurines discovered at Choga Mami is intact: the heads are all broken and the presence of single legs with thin, flat inner surfaces suggests that the breakage was deliberate. Researchers believe that there was some kind of "contract" in place at the time the statues were broken.[101] Some statuettes have elongated skulls and wide-open "coffee-bean" eyes. As in the Hassuna phase, the eyes and necklaces are often made of an external material, over-added or inlaid: the pupil is made of mother-of-pearl, and the thick, black eyebrows of bitumen. A technique reminiscent of future Sumerian production.[100] These figurines seem to indicate a practice of cranial deformation - already attested in the pre-Ceramic Levant[80] - which spread until the last phase of the Ubaid period. Such deformation can also be seen on some skeletons from the Ubaid phase at Eridu and Tell Arpachiah. This practice seems to have been carried out by a ruling class no doubt seeking to demonstrate that it was no longer possible for them to carry loads on their heads.[101]

Levels III and IV at Tell es-Sawwan confirm the use of the "tripartite" Mesopotamian house plan already discovered in the Hassuna period, but in the shape of a capital T.[nb 3] These levels were also characterized by Samarra pottery and a second type of building, which appears to have served as "granaries". These levels were also distinguished by Samarra-style pottery and by a second type of building that appears to have been used as a "granary", identified by its lime-covered floor and containing agricultural implements. All these houses, surrounded by a mud-brick wall (also visible at Choga Mami)[94] and a ditch, are composed of remarkably small rooms. This suggests the use of a flat roof for daily[102] activities or implies the presence of a floor covering the entire surface,[94] accessed by a staircase. The latter configuration could imply a division of activities between two levels: on the first floor are the service areas, storerooms, and workshops, where animal life takes place; on the first floor are the living quarters, a series of rooms, and various bedrooms.[103] The use of molded mud brick has been documented at Tell es-Sawwan, Bouqras, and Samarra. This construction method (of which a few isolated earlier attempts are known) became widespread during the Samarra period. It allowed for the standardization and rationalization of construction according to a pre-established plan. It prefigures the architecture of the ziggurats and large buildings of the Mesopotamia of the historical period.[88][94][95]

In the Samarra phase, the first Mesopotamian "public" buildings appear, evidence of social and religious activities. They can be considered the ancestors of Mesopotamian sanctuaries.[104] The tombs below the last levels of Tell es-Sawwan contained funerary objects consisting mainly of pottery and clay figurines, in stark contrast to the tombs on the first levels.[102]

Choga Mami, about 2 kilometers from the Iranian border, northeast of Baghdad, was built on a communication axis alongside the Zagros, where water is available. Here, the houses were built very close together, with large, separate courtyards, perhaps used as work areas.[101] Inhabitants of the Samarra period raised sheep and goats and hunted gazelle and auroch. In low-rainfall southern Mesopotamia, farmers had to resort to irrigation to fertilize soil that was already prone to erosion and salinization. It was at Choga Mami that the first traces of irrigation canals were discovered.[105]

By the end of the Samarra period, seals and other "contractual" devices were more widely used in central and northern Mesopotamia. Only a small number of such seals appear in southern Mesopotamia, but this absence may be due to difficulties in exploring the sedimentary layers of the region.[95][104]

The Halaf culture

In Upper Jezirah and the rest of Upper Mesopotamia, the Halaf culture (c. 6100 BC - 5200 BC) developed alongside the Samarra culture. It was named after the site where the first examples of richly decorated pottery were discovered in 1929: the Tell Halaf site on the Turkish-Syrian border.[107] Additional shards of this pottery were later discovered in Nineveh, Tell Arpachiyah (both on the outskirts of present-day Mosul), and in many other places, such as Chagar Bazar, Tepe Gawra, Yarim Tepe, also in northern Syria (Yunus Höyük) and in southeastern Anatolia at Domuztepe. Along with Anatolian obsidian, Halaf pottery is the most widely distributed of all types of ancient ceramics, found from the Zagros to the Mediterranean, a distance of around 1,200 kilometers.[80] But it was in the Belikh valley, at the Tell Sabi Abyad site, that the earliest remains of this culture were discovered.[108] It was here that late Samarra-type pottery was discovered, referred to here as "transitional Halaf", which evolved into true early Halaf, thus determining the origin of the Halaf culture, initially thought to be located in north-eastern Anatolia.[80]

The Halaf culture is thus characterized by pottery that follows in the footsteps of that of Samarra, but is technically more sophisticated. So much so, in fact, that it attests to a much greater degree of specialization by the potters, which was already evident during the Samarra period. These potteries, with their very fine paste, were subjected to a hotter, more oxidizing firing process, giving them an orange or buff color.[109] Shaped using a "tournette" (slow wheel turned by hand),[110] the first rotary method of shaping ceramics, they are made from carefully selected local clays. They were generally fired in kilns with a round or oval base and an ascending draft. These were equipped with single-chamber kilns (pottery and fuel in the same chamber), gradually being replaced by double-chamber kilns (pottery and fuel separate), which allowed better heat distribution in the objects to be fired.[111] Initially dominated by geometric motifs - triangles, squares, checkerboards, crosses, festoons, small circles, and cross-hatching - pottery decorations gradually took on more complex decorative schemes, including highly stylized plant and animal motifs such as resting birds, gazelles, and cheetahs. Other motifs are undoubtedly more religious, such as bucraniums (stylized bull heads), double axes, or "Maltese squares" (a square with a triangle at each corner). Excavations on the Euphrates have revealed black and red bichrome decorations and, in smaller numbers on the banks of the Khabur, polychrome decorations combining red, black, and white.[112][113]

-

Dish with painted decoration, Late Halaf (c. 5600-5200 BC), Tell Arpachiyah. British Museum.

-

Painted bowl, Late Halaf (c. 5600-5200 BC), Tell Arpachiyah, Iraq. British Museum.

-

Painted jar, Late Halaf (c. 5600-5200 BC), Chagar Bazar, Syria. British Museum.

-

Broken pottery (shard). The exterior is painted with a bucranium. Tell Arpachiyah, Iraq. Halaf period (6000-5000 BC). British Museum.

-

Shard of pottery decorated with a snake sticking out its tongue. Tell Arpachiyah, Iraq. Halaf period (6000-5000 BC). British Museum.

Halaf-type pottery seems to have been made in specialized centers such as Tell Arpachiyah, Tell Brak, Chagar Bazar and Tell Halaf.[113] At Tell Arpachiyah, beneath the upper Ubaid-dated levels, archaeologists have uncovered what appear to be pottery workshops or stores, as numerous pottery-making and cutting tools were present: stone and obsidian objects, a large number of flint and obsidian cores. This level has been completely burnt, apparently deliberately, probably for ritual reasons. Tell Arpachiyah may well have been a special religious site: an area of round buildings (wrongly assimilated to the tholos of Mycenae),[nb 4] surrounded by a perimeter wall, contains numerous burials, but, unlike the round constructions of other places, contains no trace of habitation.[107]

Once the pottery had been produced in the center of the village, it was transported via intermediate centers to more distant destinations, notably as far as the Persian Gulf, in exchange for other products.[113] Apart from these production centers, the villages of the Halaf culture have the common characteristic of often being very small. The expansion of this culture seems to take place from one village to the next: as soon as a village exceeds a hundred inhabitants, settlers move away to build a new village nearby.[115] For prehistorian Jean-Paul Demoule, this is the hallmark of a low-hierarchical society evolving in small human agglomerations.[116] For Georges Roux, "nothing indicates a brutal invasion, and everything we know about them points to the slow infiltration of a peaceful people".[113] Nevertheless, for researcher Joan Oates, there is ample evidence of deliberate cranial deformation in this culture, a "practice with considerable elitist potential" already mentioned in the section devoted to the Samarra period. At Tell Arpachiyah, the dentition found on the deformed skulls indicates that their bearers were genetically related, suggesting the constitution of an elite family group.[80]

Another remarkable aspect of the Halaf culture is the female figurines of parturients, typical of this culture. They depict a seated woman supporting her breasts with her arms. The body is decorated with lines and strokes that appear to represent tattoos, jewelry, or clothing. The head is often represented by a flattened neck stump, sometimes with two large eyes. These may be talismans against sterility.[113]

The Halaf culture features circular constructions referred to as "tholoi" by archaeologists, most of which were actually dwellings (unlike the tholoi of Mycenae). Built of adobe or brick on pebble bases, they sometimes featured a quadrangular extension and were covered by a cupola. The seeds of domesticated and dry-farmed plants collected in the villages are indicative that, like their contemporaries in Samarra and Hassuna, the inhabitants of the round houses of the Halaf culture were largely sedentary farmer-breeders. This does not exclude the existence of itinerant shepherds between base villages and transhumance camps occupied on a seasonal basis. The bones found are those of common animals such as sheep, pigs, goats, and oxen.[113][115][118]

It is worth noting the marginal existence of a form of hunting that evolved from a collective practice, characteristic of the PPNB, to a more individual hunt practiced by a smaller group of people. This type of hunting, based on the bones of wild animals (gazelles, onagers, deer, fallow deer, and roe deer), seems to be more important in communities located in the south, where the steppes are more arid. The product of this hunt may have been exchanged for plant products cultivated further north. Primarily for food, it is also used to protect herds, fields, and livestock. However, Halafian arrows, probably coated with poison, are rare and made from local flint, often of poor quality, and more rarely from obsidian. Most of the arrows found are still unused. Consequently, other perishable weapons such as slings or traps may have been used.[119]

At Tell Sabi Abyad, archaeologists have uncovered around 300 seal impressions made in clay, although their original seals cannot be traced. These impressions seal transportable containers, baskets, or vases. Far more numerous than those already discovered for the Samarra period, these prints depict caprids, plants, and geometric motifs. As with Samarra, it is difficult to deduce any meaning from them, other than that they could be part of an administrative practice of the "contract" type, or reflect a desire to control the circulation of goods or merchandise. Other seal impressions dating from the late Halaf period have also been discovered at Tell Arpachiyah.[57][120]

Development and dissemination of Ubaid culture

The long Ubaid period (c. 6500 BC - 3900 BC) refers to a late Neolithic and an early Chalcolithic phase of prehistory and is named after the site of Tell el-Ubaid, not far from Ur. There, in 1924, Leonard Woolley, while directing the excavation of a Sumerian temple, discovered numerous monochrome potteries bearing witness to a different culture.[78] Frustrated and less meticulous than the ceramics of the Halaf culture, this pottery, often hastily decorated with geometric motifs and sometimes inspired by nature,[121] was also discovered in a nearby ancient cemetery.[78]

Later, the remains of the city of Eridu provided the first important information about the architecture of the Ubaid culture.[122] Subsequently, the discovery in the 1980s of the Tell el-'Oueili site, north of the modern city of Nassiriyah, revealed the much older nature of the Ubaid culture and pushed back its origins to around 6500 BC, thus attributing Tell el-Ubaid to a very late phase of its eponymous culture. The term "Ubaid culture" is therefore a rather conventional appellation that does not reflect any real continuity or uniformity of this culture.[78]

Researchers have identified six successive phases, numbered from 0 to 5, and named after representative sites, based on visible changes in the forms and decoration of ceramics related to this culture. Early Ubaid is mainly documented by the sites of Tell el-Oueili (Ubaid 0 and 1), Eridu and Haggi Muhammad (Ubaid 1 and 2), which are the oldest known sites in Lower Mesopotamia (c. 6500 BC - 5300 BC). The last phases 3, 4, and 5 are documented by Tell el-Ubaid itself,[115][124] but are above all marked by the spread of the Ubaid culture to northern Iraq and northeastern Syria in the middle of the 6th millennium BC, with Tepe Gawra, northeast of Nineveh, and Zeidan, near the confluence of the Khabour and Euphrates rivers, as significant sites.[110] The Ubaid culture also seems to have spread southwards: sites related to the Ubaid culture are also found in Kuwait, with evidence of boat use suggesting the development of fishing and perhaps even the presence of pearl-seeking divers. Seasonal sites are also attested along the northeast coast of Saudi Arabia and in Qatar. Shards linked to the Ubaid culture have also been found in the southern Emirates.[110]

Until the end of the 5th millennium B.C., the egalitarian, non-stratified character of Ubaid culture communities is generally accepted: as in Late Neolithic communities, temporary and cyclical leadership - based on a communal corporate identity[125] - seems to be in the hands of the Elders. The scarcity of marks of status and differentiation in the remains, and the virtual absence of luxury, exotic, or prestige objects, in villages that were generally small in size and with very few differences in individual architecture, are indicators of a type of organization with little hierarchical structure. Added to this, even on sites that were probably of regional importance, is the scarcity of seals linked to administrative control and an apparent lack of specialization in trades.[125] It was not until the last centuries of Tell Abada's occupation (end of 5th millennium BC) that archaeologists observed specialized activity in the manufacture of ceramics and the intensive use of marker tokens, a sign of more elaborate administrative management.[126]

Southern Ubaid culture

Described as "islands enclosed in a marshy plain", still evoked in the impressions of cylindrical seals from the late 4th millennium BC,[127] the sites discovered so far in southern Mesopotamia are located on so-called "turtle shell" terraces, the remains of stepped alluvial terraces incised during the Pleistocene that, seen from the air, evoke the patterns of a turtle shell. These sites, like Hadji Muhammed and Ras al-Amiya, were discovered accidentally during modern construction work, as they lie deep beneath thick layers of alluvium carried by the streams of the ancient Mesopotamian delta. It is therefore likely that many other sites remain unexplored under a thick layer of sediment.[80][124][128]

The oldest explored levels of the Ubaid culture are found at Tell el-Oueili. Dated to 6200 BC using carbon-14 measurements, they lie just above a water table. The water table prevents archaeologists from reaching the virgin soil, leaving one or more archaeological layers currently unexplored, and it doesn't appear that occupation of the site didn't begin until 6200 BC, such is the high level of Neolithization of the populations on the levels that can be explored. They were already cultivating cereals such as wheat and barley, while beef, pork, sheep, and goats were domesticated.[78] In addition, the Oueili levels of Ubaid 0 have yielded pottery closely related to that of Choga Mami - attesting to contacts with the Samarra culture - female figurines and tripartite buildings similar to the Proto-Hassuna of Tell el-Sawwan.[129]

However, the buildings are much larger than those at Tell es-Sawwan: wooden posts support the roof, while staircases lead up to terraces and a vast living room with a fireplace, a possible venue for family gatherings that seem to have brought together two generations. Adjoining this room are a number of small rooms, each with a hollow fireplace, probably providing private spaces for a nuclear family. In addition, another large outdoor structure with huge basements appears to be a large communal attic. All these constructions are pre-designed using life-size plans drawn on the ground. These plans are elaborated from a unit of measurement of around 1.75 m (5′ 9″) - that's six feet of 0.29 m (0′ 11″). In addition, familiarity with certain geometric properties of triangles enabled right angles to be drawn. The walls are made of mud bricks pressed between two planks. The tops of these bricks are convex, with fingerprints that help them adhere to the mortar. It wasn't until the middle of the 6th millennium BC (Ubaid 1) that bricks of uniform size were molded into a frame. They were also used in the construction of more numerous but narrower granaries.[78][129]

Generally speaking, despite the apparently wetter climate of the time, irrigated agriculture seems to have gradually developed, while leaving some room for the exploitation of marshes (fish, reeds), another major factor in the development of human communities in southern Mesopotamia.[124][130] Date palms, wheat, and barley were also cultivated. Cattle and pigs were raised alongside smaller numbers of sheep and goats.[127]

During the Ubaid 2 and 3 periods, certain buildings were enlarged to such an extent that the archaeological community was divided over their use.[131][132] For others, the religion of the time still seems to have been practiced in small sanctuaries, and the large buildings discovered under the Eridu ziggurat seem more likely to have been used for meetings,[78][133] or to welcome visitors in the manner of today's mudhif of the Marsh Arabs of southern Iraq.[134] Pascal Butterlin hypothesizes that community buildings rubbed shoulders with those reserved for worship, both built in the tripartite model and expanding over the centuries. Later, during the Uruk period, the size of buildings in Uruk seemed to increase more rapidly than those north of Mesopotamia at Tepe Gawra or Tell Brak.[135]

Northward expansion

The third Ubaid phase (c. 5200 BC - 4500 BC) was marked by expansion into northern Iraq and northeastern Syria: pottery and utilitarian objects such as clay grinders and figurines identical to the sites discovered in the south are found at more northerly sites like Tell Arpachiyah and Tepe Gawra near Mosul, Tell Zeidan on the Middle Euphrates and as far as Değirmentepe in eastern Anatolia, where the first traces of copper metallurgy appear.[136] While it's well established that the spread of Ubaid culture was spread over several centuries by a slow, gradual, and peaceful change, its mechanism still remains the subject of debate.[137] For Joan Oates, this propagation is the product of cultural movements through marriages or exchange systems.[110] For Jean-Daniel Forest, the Halaf culture, in its progression towards southern Mesopotamia, was forced to adopt irrigated agriculture, imitating the Ubaid culture already in place, to such an extent that the latter rapidly replaced the Halaf culture to the north.[78] Unless it was a new way for people to express their identity through new objects in their daily lives, notably a style of pottery very similar to that of the South, but with different, more naturalistic decorative motifs, and whose color tended more towards red than that of Halaf pottery and that of the southern Ubaid culture.[137][138]

Around the middle of the 6th millennium BC, the circular, tholoi-type houses of the Halaf culture were gradually replaced by rectangular, multi-room houses typical of the Northern Ubaid period. Most of these were laid out according to a tripartite plan: the smaller rooms were often arranged symmetrically around a large central hall. This type of building is found at Tell Abada in the Hamrin basin, where it is characterized by regular buttresses, at Tepe Gawra in northern Iraq and as far away as Değirmentepe in Anatolia. Tell Abada also has a hydraulic piping system that brings water from a nearby spring and wadi to a cistern inside the village. The village also seems to have specialized in pottery manufacture: the oldest evidence of potter's wheel use can be found here, dating back to the 6th millennium BC.[126][139]

The culture's treatment of the dead seems to have gradually become more uniform. Whereas the Halaf culture showed great diversity, the Ubaid culture was content with burials in simple tombs equipped with a few ceramic vessels, with no apparent social differentiation. While Tell Arpachiyah has a small Ubaid cemetery outside the domestic dwellings, similar to the larger contemporary cemetery at Eridu in southern Mesopotamia, burial within the village seems to have been limited to the burial of infants under the houses. The same is true of Abada, where fifty-seven infant urns were found in the basements of large buildings.[87][140]

The emergence of towns

Late Chalcolithic Mesopotamia - which includes the end of the Final Ubaid period (c. 4000-3900 BC) and the Uruk period (3900-3600 BC) - witnessed a society that gradually became hierarchical around influential families occupying large houses in which no agricultural tools were found. These were adjacent to what are now recognized as temples built in towns that grew considerably in size, dominating neighboring villages to the point of taking on an urban or "proto-urban" character.[141][142] What's more, it appears that these temples housed a sacred class destined to legitimize the new secular "officiants" with whom it was intimately linked.[143]

The discovery at Uruk of a series of tablets written in symbolic signs - the first of their kind - reflects the activity of a complex, stratified administration. Among these texts is the List of Titles and Professions. It probably dates from after the 4th millennium BC, but its compilation seems to illustrate an earlier situation that clearly indicates a four-level hierarchical society, with various professions, as well as economic and political groups, becoming increasingly complex.[144][145]

All these elements go hand in hand with the emergence of cities that seem to evolve from two geographic poles: those in northern Mesopotamia, such as Tell Brak or Tepe Gawra, and those in the south, such as Uruk. At the beginning of the 4th millennium B.C., the cities of these two poles developed independently.[146]

However, from the middle of the 4th millennium BC, the development of the northern cities tended to slow down: they stopped growing and even began to shrink. At this time, relations between the two regions of north and south seemed to become unbalanced, leading to a kind of "colonization" of northern cities by southern ones. This colonization, more often than not economically motivated, took place along the trade routes of northern Iraq, northern Syria and southeastern Turkey, and can be recognized by the dominance of pottery with forms characteristic of the southern Mesopotamian city of Uruk, and by certain types of construction, seal design, and sealing practices.[146]

Habuba Kabira is a case in point: the Syrian site in the Middle Euphrates region shows such close links with southern Mesopotamia that this city and its religious center near Jebel Aruda are considered a "colony" of Uruk.[147] Tripartite houses with outdoor spaces and sometimes large reception halls were built along streets organized around the gates of a massive wall. They were surrounded by a dense assembly of smaller houses. This latter urban layout could have been similar to that of Uruk, whose site is still only partially uncovered. At Haçinebi Tepe, on the Turkish Euphrates near the modern town of Birecik, local ceramics are found alongside pottery from southern Mesopotamia.[148]

Towards the end of the 4th millennium BC, colonization of Uruk seems to have come to a halt: the use of southern-style pottery diminished and disappeared. But this is not always followed by a simple and immediate rebound of northern political structures: the lower town of Tell Brak, for example, was abandoned and the site declined significantly. By contrast, in Arslantepe, where Uruk's colonization seems to have been less overwhelming, a new type of elite emerges, apparently based more on personal power than on temple institutions.[148]

Resource exchange and control

While it has now been demonstrated that irrigated agriculture in the South - using the spider-seed ards and wagons in particular - was not the sole cause of the centralization of social organization, it did produce a food surplus that was used to maintain specialists, leaders, priests and craftsmen who did not produce their own food. This food surplus - accompanied by pearls and fish - was also traded between the southern elite and those in the north, where dry farming was less intense, but where copper ore, precious stones, obsidian (southeast Turkey), and timber were available, woolly sheep were raised to make cloth, and the potter's wheel (already known by the middle of the 6th millennium BC) was introduced.[148][149][150][151]