Kintpuash

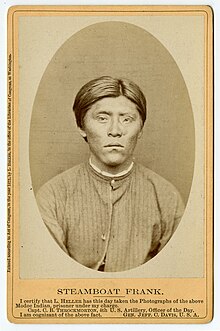

Kintpuash "Captain Jack" | |

|---|---|

Kintpuash in 1864 | |

| Chief, Modoc people | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1837 Tule Lake area, California |

| Died | October 3, 1873 (aged 35–36) Fort Klamath, Oregon |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Military service | |

| Battles/wars | Modoc War |

Kintpuash, also known as Kientpaush,[1] Keintpoos,[2] and Captain Jack (c. 1837 – October 3, 1873), was a chief of the Modoc tribe of California and Oregon. Kintpuash's name in the Modoc language means 'strikes the water brashly.'

He led a band of Modocs from the Klamath Indian Reservation to return to their lands in California, where they resisted removal. From 1872 to 1873, their small force made use of the Lava Beds, holding off numerically superior US Army forces for months in the Modoc War. Kintpuash was the only Native American leader ever to be charged with war crimes. He was executed by the Army, along with three tribesmen, for their ambush killings of General Edward Canby and Reverend Eleazar Thomas at a peace commission meeting. The Modoc leaders were hanged for "murder in violation of the laws of war" by the Army.

Life

The Modoc Tribe

Kintpuash was born around 1837 in Modoc territory near Tule Lake, in present-day California. The Modocs considered Tule Lake sacred, marking the site where the deity Kumookumts began creating the world. In a process likened to basket weaving, Kumookumts started the creation with a hill near the lake, expanding outward to form the land. Modoc territory straddled what is now the California-Oregon border. Known for their craftsmanship, the Modocs wove baskets from tule reeds, reflecting their connection to the land and its resources. They lived in semi-nomadic bands, that migrating seasonally between Mount Shasta and the areas northward beyond Lost River, sustaining themselves through hunting and gathering. Modoc men hunted various animals, including deer, antelope, rabbits, and ducks, while women gathered essential plants such as waterlily seeds and epos root, a dietary staple.[3]

Contact with fur traders began in 1824, about thirteen years before Kintpuash's birth. This interaction brought diseases that devastated the Modoc population, reducing their numbers from approximately 1,000 to just 300 by 1860.[4] The situation worsened after the 1851 discovery of gold in the region, which drew waves of settlers. The arrival of wagon trains, livestock, and settlers disrupted the Modoc food supply by scaring away game and destroying essential foraging grounds. In response, the Modocs took defensive actions, including attacking settlers and killing unattended livestock to protect their resources. Tensions escalated as settlers claimed the most fertile lands, further marginalizing the Modocs and deepening the friction between the two groups.[5] Kintpuash's early life and the history of the Modoc people reflect the devastating effects of settler encroachment and disease, which drastically reduced their population and disrupted their traditional way of life.

Rise to Leadership

Kintpuash demonstrated diplomacy and pragmatism from an early age. He objected to the Modoc chief's calls for armed resistance against settlers and the U.S. government, believing that the tribe's survival depended on peaceful relations with the newcomers. According to historian Gary Okihiro, citing Alfred B. Meacham's writings, in 1852, when Kintpuash was about fourteen, the bodies of eighteen white settlers were discovered in Modoc territory. In response to these deaths, California Militia leader Ben Wright proposed a meeting with Modoc leaders under the pretense of peace talks. However, the meeting was a ruse. The gathering ended in a massacre, with Wright and his men killing over forty Modocs. Wright continued to other Modoc villages, destroying homes and displacing families. This event, later known as Ben Wright’s Massacre, also claimed the life of the Modoc chief. In the aftermath, Kintpuash rose to leadership, becoming the new chief of his people.[6]

As chief, Kintpuash built friendships and trade relationships with settlers. In Yreka, where many Modocs conducted trade, settlers mockingly nicknamed him Captain Jack, a name he embraced along with settlers' clothing, structures, and wagons. By the time of the U.S. Civil War, tensions between the Modocs and settlers worsened. The Modocs occasionally killed settlers' livestock for food or used their horses without permission. While some settlers saw these actions as compensation for occupying Modoc land, others advocated for Modoc removal.[7] Kintpuash sought a balance between diplomacy and resistance, building relationships with settlers while navigating escalating tensions that ultimately pushed his people toward conflict.

Modoc Removal

Council Grove Treaty

In 1864, Indian Affairs officials in Oregon signed the Council Grove Treaty with the Klamath and an Oregon Modoc band, requiring them to move to the Klamath Indian Reservation. Kintpuash, under pressure, reluctantly signed reluctantly to protect his California band. The federal government claimed the treaty forfeited the Modocs' rights to their ancestral lands near Tule Lake and Lost River in California, granting them land at Klamath instead. However, the Modocs argued that Kintpuash had already signed an agreement with California Indian agents permitting them to remain in their homeland. Facing violence from settlers and government pressure, Old Schonchin’s band relocated to Klamath, with Captain Jack leading his followers there the following year. Life at Klamath proved difficult. The allocated lands were insufficient for survival, and government efforts to assimilate the tribe through Christianity and capitalism caused further resentment.[8]

Return to Lost River

Tensions grew as rival Klamath tribesmen vandalized and stole from lands designated for the Modocs. Supplies promised in the treaty, including horses, wagons, and food, failed to reach the Modocs. Meanwhile, the larger Klamath tribe received federal provisions, further exacerbating tensions.[9] This period marked a significant turning point in Modoc history, illustrating the challenges of forced relocation and the consequences of federal treaty violations.

In 1865, Kintpuash led his band back to their ancestral home in California. After the 1869 ratification of the Council Grove Treaty, the Modocs were promised new lands on the Klamath Reservation, and the U.S. government offered food and blankets as incentives for their return. While some Modocs voluntarily returned, forty-five were forcibly relocated. Conditions on the Klamath Reservation continued to be marked by harassment and assimilation efforts, leading to widespread dissatisfaction among the Modocs.[10]

During this period, the Ghost Dance movement, a spiritual and cultural revival led by figures such as the Paiute prophet Wovoka, spread among Native American tribes across California, Nevada, and Oregon. The movement called for dancing, prayer, and fasting to bring about removal of settlers and the revival of deceased Native Americans. For the Modocs, embracing the Ghost Dance symbolized resistance and resilience. It provided a spiritual framework to oppose cultural erasure and reaffirm their connection to their ancestral lands. While primarily a spiritual movement, it was also linked to armed resistance and efforts to restore Native sovereignty.[10] This alignment of spiritual and political resistance echoed the broader struggles of the Modocs, who struggled to keep their homeland and autonomy.

In April 1870, deteriorating conditions at Klamath prompted Kintpuash and approximately 370 Modocs to abandon the reservation and return to the Lost River Valley, their ancestral homeland. Upon their return, the Modocs faced significant challenges, as settlers and livestock had overtaken fertile lands along the Lost River. To sustain themselves, many Modocs worked for settlers, supplementing traditional hunting and gathering. The Modoc exodus alarmed U.S. authorities, who viewed it as an act of rebellion. Federal Indian Commissioner Francis A. Walker ordered their return to the Klamath Reservation, authorizing the use of force if necessary.[11] This directive set the stage for increased tensions and eventual armed conflict between the Modocs and the U.S. government.

Modoc War, 1872–73

Battle of Lost River

In the summer of 1872, after two years of the Modocs evading US military forces, the U.S. Indian Bureau once again demanded that the Modocs return to the Klamath Reservation. Kintpuash refused this order and instead proposed the establishment of a reservation near Lost River. Although the Indian Bureau expressed openness to the idea, strong opposition from local settlers effectively blocked any progress. On November 28, 1872, Major James Jackson, under orders to enforce the relocation, departed from Fort Klamath with a detachment of soldiers. By the next morning, Jackson's forces had surrounded Kintpuash’s camp. With no viable alternative, Kintpuash reluctantly agreed to return to Klamath but criticized Jackson’s methods, stating that the soldiers’ approach had frightened his people.[12]

During the disarmament process, Jackson instructed Kintpuash to set down his rifle, which he did. Most of his men also surrendered their weapons, but Scarfaced Charley, a Modoc leader, retained his pistol. When soldiers attempted to disarm him, Scarfaced Charley fired, sparking a sudden exchange of gunfire. One soldier was killed, and others were wounded. Amid the chaos, Kintpuash and his people fled the camp and sought refuge in the nearby Lava Beds, a natural stronghold near Tule Lake.[13]

The following morning, Jackson’s forces pursued another Modoc Band led by Hooker Jim. At Hooker Jim’s camp, soldiers killed an elderly woman and a baby. Enraged, Hooker Jim and his band retaliated, killing twelve settlers before fleeing to join Kintpuash in the Lava Beds. Kintpuash, distressed by these killings, feared he would be held accountable.[14] The Battle of Lost River marked the beginning of the Modoc War, a conflict that highlighted the Modocs' struggle to retain their homeland and resist U.S. government policies.

Battle of the Stronghold

The Lava Beds National Monument in northern California served as a natural fortress for Kintpuash and his band during the Modoc War. The rugged volcanic terrain, later named Captain Jack's Stronghold provided significant defensive advantages. Women and children found shelter in the caves, while Modoc warriors used the terrain to resist U.S. Army attacks. By January 16, over 300 U.S. soldiers arrived to confront the Modocs. Kintpuash, advocated for surrender to protect his people, expressing willingness to face consequences alongside those responsible for prior violence. However, other influential Modoc leaders, including Hooker Jim and Curly Headed Doctor, opposed surrender. In a vote, only fourteen of the fifty-one Modoc warriors supported Kintpuash.[15]

The following day, January 17, the U.S. Army launched an assault on the Modocs. using the terrain and camouflage, the Modocs repelled the attack, killing thirty-five U.S. soldiers and wounding many more without sustaining casualties. This unexpected victory prompted the Army to request reinforcements.[16] The battle demonstrated the Modocs' strategic use of their stronghold and their ability to resist overwhelming military pressure.

Peace Commission

On February 28, 1873, Winema, a Modoc relative married to settler Frank Riddle, visited Kintpuash with a message from President Ulysses S. Grant announcing a peace commission. to negotiate with the Modocs under a truce. This commission aimed to return the tribe to Klamath peacefully and included General Edward Canby, California clergyman Eleazar Thomas, Klamath Reservation subagent L.S. Dyar, and Alfred B. Meacham, a former Indian Affairs agent for the Modocs in Oregon. The Modocs sought clarity about the fate of Hooker Jim and his band, who had killed twelve settlers. The commissioners assured the Modocs that Hooker Jim’s group would be relocated to a reservation in either Arizona or Indian Territory.[17]

Encouraged, Hooker Jim's group initially agreed to surrender. Canby, eager for a resolution, sent word to General William Tecumseh Sherman, the overall commander of the U.S. Army, for further instructions. However, Hooker Jim's group, left unsupervised, encountered an Oregon man who warned them that Oregon authorities intended to hang the Modocs as criminals. This threat terrified Hooker Jim and his followers, prompting them to flee back to the Lava Beds. Their fears proved justified when pressure from Oregon officials led Canby to rescind the promise of amnesty.[18] The incident deepened mistrust between the Modocs and U.S. authorities, complicating the peace process and intensifying the conflict.

On March 6, 1873, Kintpuash, with the assistance of his sister Mary, penned a letter to the peace commissioners. In it, he expressed his inability to surrender any of his men and asked whether the white settlers responsible for killing Modocs would face justice. Despite these calls for a peaceful resolution, Canby continued to amass reinforcements, positioning them closer to the Lava Beds, further eroding the trust between the two sides. On April 2, Kintpuash requested a meeting with the commission. At this meeting, he asked Canby to withdraw his soldiers, a request Canby denied. Kintpuash again sought clarity about the fate of the wanted Modocs, only to be told that no amnesty would be granted.[19]

Later, Kintpuash requested a private meeting with Meacham and John Fairchild, an old friend and ranch owner. Excluding Canby and Thomas due to mistrust of the military and clergy, Kintpuash explained to Meacham his decision to flee to the Lava Beds, citing the soldiers' actions during the confrontation at Lost River. Reiterating his desire for land along Lost River, Kintpuash was informed that this was impossible. When he asked for permission to remain in the Lava Beds, Meacham insisted that the Modocs surrender Hooker Jim and the other killers. Kintpuash countered by asking whether the soldiers who killed Modoc women and children at Lost River would be punished, but Meacham dismissed this as well. Kintpuash concluded the discussion by stating that further tribal deliberation was necessary.[20]

After Meacham informed Canby that the Modocs would not surrender Hooker Jim, Canby sent Winema to the Lava Beds with a message: any Modoc who wished to surrender could leave safely with her. In the tribal meeting that followed, only eleven members supported surrendering. However, Hooker Jim, Schonchin John, and Curly Headed Doctor opposed this idea, accusing Canby of deceit and threatening to kill anyone who attempted to leave. As Winema departed, she was warned by a Modoc that Hooker Jim was plotting to assassinate the American negotiators. Despite the warning, Canby and the commissioners dismissed the possibility of such a plot, underestimating the rising desperation among the Modocs.[21] This critical period in the Modoc War highlights the breakdown of negotiations and the growing divide between the Modocs and U.S. authorities, setting the stage for further tragedy.

Assassinations

On April 7, 1873, tensions within the Modoc leadership reached a critical point as Hooker Jim and his allies confronted Kintpuash, accusing him of planning to surrender the wanted men. Schonchin John and Black Jim called for immediate action, urging the assassination of the commissioners before Canby could complete the military buildup. Kintpuash sought to de-escalate the anger, pleading for patience to secure favorable land and amnesty. However, Black Jim and other warriors demanded that Kintpuash promise to personally shoot Canby. When Kintpuash refused, Hooker Jim escalated the pressure, threatening to kill Kintpuash if he did not comply. The situation deteriorated further when his opponents humiliated him by throwing women’s clothing at him and calling him a woman. To preserve his authority as chief and buy time, Kintpuash reluctantly agreed to the assassination.[22]

Following this decision, a meeting was arranged with the commission for April 11. Both sides agreed to attend the meeting unarmed. Despite his agreement to the assassination, Kintpuash continued to warn of the dire consequences of violence. He reminded them that the entire Modoc tribe could face annihilation if they chose to fight and implored them to abandon their plans. Kintpuash brought the matter to a vote among the warriors, but the majority overruled his caution. Realizing he had lost control over the situation, Kintpuash made one final appeal for a peaceful resolution, and the warriors agreed to his request to attempt one last negotiation.[23] This fraught internal dynamic illustrates the divisions and desperation within the Modoc tribe as they faced increasing pressure from U.S. forces.

On April 11, 1873, Kintpuash and several key Modoc leaders—Hooker Jim, Shacknasty Jim, Black Jim, Schonchin John, and Ellen’s Man—met with the peace commission. The commissioners were accompanied by Winema, her husband Frank Riddle, Boston Charley, and Bogus Charley, with the latter two serving as interpreters. According the writings of Jeff C. Riddle, the son of Winema and Frank Riddle, historian Dee Brown noted that Kintpuash reiterated his demand for the Modocs to remain in their homelands and for the removal of U.S. soldiers from the area. Canby responded that he lacked the authority to withdraw the troops. Schonchin John interjected, threatening to end negotiations unless the Modocs are granted Hot Creek and Canby withdrew immediately. Realizing that Canby would not concede to their demands, Kintpuash gave a signal in Modoc. He drew a pistol and fired at Canby. Initially, the pistol misfired, stunning Canby, but Kintpuash fired again, killing him. Boston Charley then killed Thomas, while Meacham, Dyar, Winema, and Riddle survived.[24]

Betrayal

Following the assassination, the Modoc warriors quickly retreated to the Lava Beds. Three days later, the U.S. Army launched a massive assault on the area but was unable to locate the dispersed Modocs, who had scattered to avoid capture. However, their situation became increasingly dire as they ran out of water and provisions in the following weeks. Facing inevitable defeat, the unity of the Modoc tribe collapsed. Hooker Jim and his followers abandoned Kintpuash, reducing his forces to fewer than forty warriors.[25]

Seeking a way to save himself, Hooker Jim surrendered to the Army and proposed betraying Kintpuash in exchange for amnesty. On May 27, Hooker Jim located Kintpuash and urged him to surrender. Kintpuash, angered by the betrayal, refused. Days later, exhausted and resigned to his fate, Kintpuash surrendered voluntarily. He was wearing Canby’s uniform and stated that he was tired and prepared to face death.[26] This dramatic conclusion marked the end of the Modoc War, one of the most significant Native American uprisings of the 19th century. Kintpuash's resistance and eventual surrender remain a symbol of the Modoc struggle for their homeland and survival in the face of overwhelming odds.

Trial and Execution

Reaction to Assassinations

The assassination Canby marked a grim milestone in U.S. history, as he became the first American general to be killed by Native Americans. In response, General William Tecumseh Sherman remarked that executing the Modocs responsible for Canby’s death would be justified. According to historian Benjamin Madley, citing correspondence between military leaders, the Army decided to halt plans for the extermination of the Modocs after Kintpuash was captured. Several factors influenced this decision. In 1873, Native Americans in California gained the right to serve as witnesses in trials, marking a shift in how their testimony could influence legal outcomes. Additionally, Native advocates lobbied President Grant for clemency, warning that annihilating the Modocs could provoke both domestic and international condemnation. Grant, wary of such a scenario, chose not to pursue a genocidal course of action.[27]

Despite these developments, animosity toward the Modocs persisted. Oregon militiamen attacked a wagon transporting captive Modocs, killing four men and one woman. The conclusion of the Modoc War in 1873 also marked the end of the larger genocidal campaign against California’s Native population.[28] The events of the Modoc War remain a stark reminder of the complex and often brutal history of U.S. westward expansion and Native resistance.

The assassination of Canby shocked and angered much of the American public, as Canby was a widely respected military veteran who had been wounded during the Civil War. The U.S. Attorney General determined that the captured Modocs would be tried by a military tribunal, under the reasoning that they were prisoners of war from a sovereign nation engaged in conflict with the US. After the Modoc resistance was subdued, the remaining tribe members were transferred to Fort Klamath, where they were confined.[29] During the trial, Kintpuash, Black Jim, Boston Charley, and two younger prisoners, Slolux and Barncho, were prosecuted.

Legal Proceedings

The tribunal's judicial panel was composed of five officers, four of whom had been subordinates of Canby. According to historian Doug Foster, who also relied on Meacham's account as well as newspapers, this composition raised concerns of bias, as these men had personal motivations to avenge their fallen commander. Additionally, the panel was appointed by Canby's replacement, General Jefferson C. Davis. However, the defendants, unfamiliar with the American legal system and unable to mount an effective defense, did not object to the proceedings. Elija Steele, a friend of Kintpuash from Yreka, sought to secure legal representation for the Modocs by requesting attorney E.J. Lewis from Colusa. However, Lewis arrived at Fort Klamath on the trial's final day, and the court refused to reopen proceedings despite being notified in advance that counsel was on the way.[30] This refusal further underscored the irregularities in the trial process.

Under court-martial regulations, the judge advocate was required to ensure the fairness of the trial, especially in the absence of legal representation, and to prevent the defendants from unintentionally undermining their cases. However, these responsibilities were neglected. The judge advocate approved the commission without informing the defendants that they had the right to replace four out of the five judicial officers. Additionally, the court made no mention of the shackling of prisoners and the use of armed guards, both of which were discouraged by military regulations.[31]

The defendants faced other significant disadvantages during the trial. Foster, citing Meacham, argued that the Modoc defendants were not proficient in English, and their translator, Frank Riddle, broke his neutrality by testifying against them. Out of ignorance of judicial procedures, Kintpuash presented his travel passes, believing they would demonstrate his good reputation among settlers; however, the military commission dismissed them as irrelevant. Kintpuash also argued that the Modocs did not initiate hostilities, stating that war was waged upon him and his people.[32]

Prosecutors relied on the Council Grove Treaty of 1864 to argue their case but omitted mention of the unratified treaty that Kintpuash had signed months earlier. From the Modoc perspective, they had abandoned the second treaty because the U.S. government had already reneged on the first. Without legal representation, critical arguments were left unvoiced, such as the claim that no truce existed when Kintpuash killed Canby. The Modocs maintained that the Army broke the truce by confiscating their horses and encircling the Lava Beds. On April 5, Kintpuash had even notified the commission that the truce agreement had been violated.[33]

Meanwhile, Hooker Jim and his three accomplices, who had betrayed Kintpuash and aligned with the U.S. government, were never tried, further demonstrating the disparity in justice. This was intended reinforce the notion among Native Americans that working against their own tribes in cooperation with the U.S. government could yield benefits. All the defendants—Kintpuash, Black Jim, Boston Charley, and Schonchin John—were found guilty and sentenced to death. However, President Grant commuted the sentences of the younger defendants, Barncho and Slolux, to life imprisonment after receiving appeals for clemency.[34]

Execution

On October 3, 1873, the executions were carried out before a large crowd. The spectacle drew widespread attention, with even an Oregon school granting students a holiday to attend. The entire Modoc tribe was forced to witness the hanging of their leaders. Adding to the grim nature of the event, the ropes used in the executions and strands of Kintpuash’s hair were sold as souvenirs, reflecting the public's morbid fascination.[35] This trial and its aftermath remain a striking example of the injustices faced by Native Americans in the 19th century, highlighting systemic inequities in both judicial and social spheres.

After the executions of Kintpuash and Schonchin John, their bodies were removed from the scaffold, and an Army surgeon decapitated them. The severed heads were sent to Washington, D.C., for scientific purposes. While the San Francisco Chronicle condemned the act as barbaric, the Army and Navy Journal justified it, claiming it was conducted for craniological research. For more than a century, the skulls of the two Modoc leaders were held in the collections of the Army Medical Museum and later transferred to the Smithsonian Institution.[36]

Exile and Return

Following the executions, the remaining members of Kintpuash's band—comprising thirty-nine men, fifty-four women, and sixty children—were forcibly relocated to Oklahoma Territory. This transfer was intended as a warning to other Native American tribes and to prevent further resistance from the Modocs. In exile, harsh living conditions and disease took a heavy toll, claiming many lives. After decades of hardship, the U.S. government permitted the surviving Modocs to return to Oregon in 1909, where they were allowed to settle on the Klamath Reservation.[37]

Legacy

- The area where the Modoc established their defense is now known as Captain Jack's Stronghold. It is part of the protected area of the Lava Beds National Monument. There is a 2-mile trail through the Stronghold providing views from the Modoc lines and the Army's lines. You can view the caves Captain Jack and Schonchin John used. There is a 3 mile hike out to the Thomas-Wright Battlefield in the Lava Beds giving you a view of the battlefield from the Modoc positions.

- Captain Jack Substation, a Bonneville Power Administration electrical substation, was named in honor of Kintpuash. It is located near what is now called Captain Jack's Stronghold. It forms the northern end of Path 66, a high-power electric transmission line.

See also

References

- ^ Ball, Natalie (20 Oct 2009). "Re-Imaging a Native American History of (Un)-Belonging". The Other Journal. 16. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). . .

- ^ Okihiro, Gary Y. (2019). The Boundless Sea: Self and History. Oakland, California: University of California Press. pp. 96–99. ISBN 978-0-520-30966-1.

- ^ Okihiro. The Boundless Sea. pp. 101–102.

- ^ Brown, Dee (2012). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Newburyport: Open Road Media. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-4532-7414-9.

- ^ Okihiro. The Boundless Sea. pp. 102–104.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. p. 284.

- ^ Okihiro. The Boundless Sea. p. 104.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 284–285.

- ^ a b Okihiro. The Boundless Sea. p. 105.

- ^ Okihiro. The Boundless Sea. p. 106.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 285–286.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 286–289.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 289–290.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 289–291.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 291–292.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 292–293.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 293–294.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 294–296.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 296–298.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 294–300.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 299–301.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 301–302.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 302–305.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. p. 305.

- ^ Brown. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. pp. 305–307.

- ^ Madley, Benjamin (2016). An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873. The Lamar Series in Western History. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 337–343. ISBN 978-0-300-18217-0.

- ^ Madley. An American Genocide. pp. 344–345.

- ^ Foster, Doug (1999). "Imperfect Justice: The Modoc War Crimes Trial of 1873". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 100 (3): 251–256. ISSN 0030-4727.

- ^ Foster. "Imperfect Justice". Oregon Historical Quarterly: 256–260.

- ^ Foster. "Imperfect Justice". Oregon Historical Quarterly: 260–262.

- ^ Foster. "Imperfect Justice". Oregon Historical Quarterly: 260.

- ^ Foster. "Imperfect Justice". Oregon Historical Quarterly: 262–264.

- ^ Foster. "Imperfect Justice". Oregon Historical Quarterly: 279–282.

- ^ Foster. "Imperfect Justice". Oregon Historical Quarterly: 282.

- ^ Foster. "Imperfect Justice". Oregon Historical Quarterly: 282.

- ^ Foster. "Imperfect Justice". Oregon Historical Quarterly: 282.

Further reading

- Arthur Quinn, Hell with the Fire Out: A History of the Modoc War (1997), includes coverage of Kintpuash.

- Jim Compton, Spirit in the Rock: The Fierce Battle for Modoc Homelands (2017), reveals motive of Jesse Applegate and Jesse Carr to take possession of Modoc territory.

External links

- "Oregon Experience: The Modoc War", Oregon Public Broadcasting, July 2012. – Video (57:14)

- Indian Country Today June 15, 2016

- 1830s births

- 1873 deaths

- American people convicted of war crimes

- Modoc people

- Native American people of the Indian Wars

- People of the Modoc War

- Executed American assassins

- Executed people from California

- Executed Native American people

- 19th-century executions of American people

- People convicted of murder by the United States military

- People executed by the United States military by hanging

- 19th-century executions by the United States military

- 1873 murders in the United States

- 19th-century Native American leaders

- People executed for war crimes