Iliad

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. |

The Iliad (Greek Template:Polytonic, [el] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: Iliás (help)) is, together with the Odyssey, one of two ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer, supposedly a blind Ionian poet, or collection of nameless poets. Most modern scholars consider the epics to be the oldest literature in the Greek language, possibly equalled by Hesiod, dated to the 8th or 7th century BC.

The poem concerns events during the tenth and final year in the siege of the city of Ilium, or Troy, by the Greeks (See Trojan War). The word "Iliad" means "pertaining to Ilium" (in Latin, Ilium), the city proper, as opposed to Troy (in Greek, Τροία, Troía; in Latin, Troia), the state centered around Ilium, over which Priam reigned. The names "Ilium" and "Troy" are often used interchangeably.

Date

For most of the twentieth century, scholars dated the Iliad and the Odyssey to the 8th century BC. Some still argue for an early dating, notably Barry B. Powell, who has proposed a link between the writing of the Iliad and the invention of the Greek alphabet. Many others (including Martin West and Richard Seaford) now prefer a date in the 7th or even the 6th century BC.

The story of the Iliad

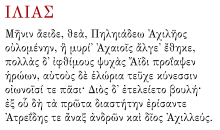

The Iliad begins with these lines:

Template:Polytonic

Sing, goddess, the rage of Achilles the son of Peleus,

the destructive rage that sent countless pains on the Achaeans...

The first word of the Iliad is Template:Polytonic (mēnin), "rage" or "wrath". This word announces the major theme of the Iliad: the wrath of Achilles. When Agamemnon, the commander of the Greek forces at Troy, dishonors Achilles by taking Briseis, a slave woman given to Achilles as a prize of war, Achilles becomes enraged and withdraws from the fighting for almost all of the story. Without him and his powerful Myrmidon warriors, the Greeks suffer defeat by the Trojans, almost to the point of losing their will to fight. Achilles re-enters the fighting when his dearest friend, Patroclus, is killed by the Trojan prince Hector. Achilles slaughters many Trojans and kills Hector. In his rage, he then refuses to return Hector's body and instead defiles it. Priam, the father of Hector, ransoms his son's body, and the Iliad ends with the funeral of Hector.

Homer devotes long passages to frank, blow-by-blow descriptions of combat. He gives the names of the fighters, recounts their taunts and battle-cries, and gruesomely details the ways in which they kill and wound one another. Often, the death of a hero only escalates the violence, as the two sides battle for his armor and corpse, or his close companions launch a punitive attack on his killer. The lucky ones are sometimes whisked away by friendly charioteers or the intervention of a god, but Homeric warfare is still some of the most bloody and brutal in literature.

The Iliad has a very strong religious and supernatural element. Both sides in the war are extremely pious, and both have heroes descended from divine beings. They constantly sacrifice to the gods and consult priests and prophets to decide their actions. For their own part, the gods frequently join in battles, both by advising and protecting their favorites and even by participating in combat against humans and other gods.

The Iliad's huge cast of characters connects the Trojan War to many Greek myths, such as Jason and the Argonauts, the Seven Against Thebes, and the Labors of Hercules. Many Greek myths exist in multiple versions, so Homer had some freedom to choose among them to suit his story. See Greek mythology for more detail.

The action of the Iliad covers only a few weeks of the tenth and final year of the Trojan War. It does not cover the background and early years of the war (Paris' abduction of Helen from King Menelaus) nor its end (the death of Achilles and the fall of Troy). Other epic poems, collectively known as the Epic Cycle or cyclic epics, narrated many of these events; these poems only survive in fragments and later descriptions. See Trojan War for a summary of the events of the war.

Synopsis

As the poem begins, the Greeks have captured Chryseis, the daughter of Apollo's priest Chryses, and given her as a prize to Agamemnon. In response, Apollo has sent a plague against the Greeks, who compel Agamemnon to restore Chryseis to her father to stop the sickness. In her place, Agamemnon takes Briseis, whom the Achaeans had given to Achilles as a spoil of war. Achilles, the greatest warrior of the age, follows the advice of his goddess mother, Thetis, and withdraws from battle in revenge.

In counterpoint to Achilles' pride and arrogance stands the Trojan prince Hector, son of King Priam, a husband and father who fights to defend his city and his family. With Achilles on the sidelines, Hector leads successful counterattacks against the Greeks, who have built a fortified camp around their ships pulled up on the Trojan beach. The best remaining Greek fighters, including Odysseus, Diomedes, and Ajax, are wounded, and the gods favor the Trojans. Patroclus, impersonating Achilles by wearing his armor, finally leads the Myrmidons back into battle to save the ships from being burned. The death of Patroclus at the hands of Hector brings Achilles back to the war for revenge, and he slays Hector in single combat. Hector's father, King Priam, later comes to Achilles alone (but aided by Hermes) to ransom his son's body, and Achilles is moved to pity; the funeral of Hector ends the poem.

Book summaries

- Book 1: Nine years into the war, Agamemnon seizes Briseis, the concubine of Achilles, since he has had to give away his own; Achilles withdraws from the fighting in anger; in Olympus, the gods argue about the outcome of the war

- Book 2: Agamemnon pretends to order the Greeks home to test their resolve; Odysseus encourages the Greeks to keep fighting; Catalogue of Ships, Catalogue of Trojans and Allies

- Book 3: Paris challenges Menelaus to single combat over Helen; He is quickly overmatched by Menelaus, but is rescued from death by Aphrodite, and Menelaus is seen as the winner.

- Book 4: The truce is broken and battle begins

- Book 5: Diomedes has an aristeia (a period of supremacy in battle) and wounds Aphrodite and Ares

- Book 6: Glaucus and Diomedes greet each other during a truce; Hector returns to Troy and speaks to his wife Andromache

- Book 7: Hector battles Ajax

- Book 8: The gods withdraw from the battle

- Book 9: Agamemnon retreats; his overtures to Achilles are spurned

- Book 10: Diomedes and Odysseus go on a spying mission

- Book 11: Paris wounds Diomedes; Achilles sends Patroclus on a mission

- Book 12: The Greeks retreat to their camp and are besieged by the Trojans

- Book 13: Poseidon encourages the Greeks

- Book 14: Hera helps Poseidon assist the Greeks; Deception of Zeus

- Book 15: Zeus stops Poseidon from interfering

- Book 16: Patroclus borrows Achilles' armour, enters battle, kills Sarpedon and then is killed by Hector

- Book 17: The armies fight over the body and armour of Patroclus

- Book 18: Achilles learns of the death of Patroclus and receives a new suit of armour. The Shield of Achilles is described at length

- Book 19: Achilles is reconciled with Agamemnon and enters battle

- Book 20: The gods join the battle; Achilles tries to kill Aeneas

- Book 21: Achilles does battle with the river Scamander and encounters Hector in front of the Trojan gates

- Book 22: Achilles kills Hector and drags his body back to the Greek camp

- Book 23: Funeral games for Patroclus

- Book 24: Priam, the King of the Trojans, secretly enters the Greek camp. He begs Achilles for Hector's body. Achilles grants him it, and it is taken away and burned on a pyre

Famous passages

- Catalogue of Ships (Book 2, lines 494-759)

- Teichoscopia (Book 3, lines 121-244)

- Deception of Zeus (Book 14, lines 153-353)

- Shield of Achilles (Book 18, lines 430-617)

After the Iliad

Although the Iliad scatters foreshadowings of certain events subsequent to the funeral of Hector, and there is a general sense that the Trojans are doomed, Homer does not set out a detailed account of the fall of Troy. For the story as developed in later Greek and Roman poetry and drama, see Trojan War. The other Homeric poem, the Odyssey, is the story of Odysseus' long journey home from Troy; the two poems between them incorporate many references forward and back and overlap very little, so that despite their narrow narrative focus they are a surprisingly complete exploration of the themes of the Troy story.

Major characters

- Main article: List of characters in the Iliad

The Iliad contains a sometimes confusingly great number of characters. The latter half of the second book (often called the Catalogue of Ships) is devoted entirely to listing the various commanders. Many of the battle scenes in the Iliad feature bit characters who are quickly slain. See Trojan War for a detailed list of participating armies and warriors.

- The Achaeans (Αχαιοί) - the word "Hellenes", which would today be translated as "Greeks", is not used by Homer

- Achilles (Αχιλλεύς), the leader of the Myrmidons (Μυρμιδόνες) and the principal Greek champion whose anger is one of the main elements of the story

- Agamemnon (Αγαμέμνων), King of Mycenae, supreme commander of the Achaean armies whose actions provoke the feud with Achilles; brother of King Menelaus

- Menelaus (Μενέλαος), Helen's abandoned husband, younger brother of Agamemnon, King of Sparta

- Odysseus (Οδυσσεύς), another warrior-king, famed for his guile and cunning, who is the main character of another (roughly equally ancient) epic, the Odyssey, is an important character in the Iliad

- Calchas (Κάλχας), a powerful Greek prophet and omen reader, who guided the Greeks through the war with his predictions.

- Patroclus (Πάτροκλος), beloved companion to Achilles

- Nestor (Νέστωρ), Diomedes (Διομήδης), Idomeneus (Ιδομενεύς), and Telamonian Ajax (Αίας ο Τελαμώνιος), kings of the principal city-states of Greece who are leaders of their own armies, under the overall command of Agamemnon

- Diomedes (Διομήδης), son of Tydeus, and a noble Greek. He was a close companion of Odysseus.

- The Trojan men and their allies

- Priam (Πρίαμος), king of the Trojans, too old to take part in the fighting; many of the Trojan commanders are his fifty sons

- Hector (Έκτωρ), firstborn son of King Priam, leader of the Trojan and allied armies and heir apparent to the throne of Troy

- Paris (Πάρις), Trojan prince and Hector's brother, also called Alexander (Aλέξανδρος); his abduction of Helen is the casus belli. He was supposed to be killed as a baby because his sister Cassandra foresaw that he would cause the destruction of Troy. Raised by a shepherd.

- Aeneas (Αινείας), cousin of Hector and his principal lieutenant, son of Aphrodite, the only major Trojan figure to survive the war. Held by later tradition to be the forefather of the founders of Rome. See the Aeneid.

- Glaucus and Sarpedon (Σαρπήδων), leaders of the Lycian forces allied to the Trojan cause.

- Pandarus, a Trojan archer whose shot at Menelaus in Book 4 breaks the temporary truce between the two sides.

- Polydamas, a young Trojan commander who sometimes figures as a foil for Hector by proving cool-headed and prudent when Hector charges ahead. Polydamas gives the Trojans sound advice, but Hector seldom acts on it.

- Agenor, a Trojan warrior who attempts to fight Achilles in Book 21. Agenor delays Achilles long enough for the Trojan army to flee inside Troy’s walls.

- Dolon (Δόλων), a Trojan who is sent to spy on the Achaean camp in Book 10.

- Antenor (mythology), a Trojan nobleman, advisor to King Priam, and father of many Trojan warriors. Antenor argues that Helen should be returned to Menelaus in order to end the war, but Paris refuses to give her up.

- The Trojan women

- Hecuba (Εκάβη), Queen of Troy, wife of Priam, mother of Hector, Cassandra, Paris etc

- Helen (Ελένη), former Queen of Sparta and wife of Menelaus, now espoused to Paris

- Andromache (Ανδρομάχη), Hector's wife and mother of their infant son, Astyanax (Αστυάναξ)

- Cassandra (Κασσάνδρα), daughter of Priam, prophetess, first courted and then cursed by Apollo. As her punishment for offending him, she accurately foresees the fate of Troy, including her own death and the deaths of her entire family, but does not have the power to do anything about it.

The Olympian deities, principally Zeus, Hera, Apollo, Hades, Aphrodite, Ares, Athena, Hermes and Poseidon, as well as the lesser figures Eris, Thetis, and Proteus appear in the Iliad as advisers to and manipulators of the human characters. All except Zeus become personally involved in the fighting at one point or another (See Theomachy).

Technical features

The poem is written in dactylic hexameter. The Iliad comprises 15,693 lines of verse. Later Greeks divided it into twenty-four books, or scrolls, and this convention has lasted to the present day with little change.

The Iliad as oral tradition

The Iliad and the Odyssey were considered by Greeks of the classical age, and later, as the most important works in Ancient Greek literature, and were the basis of Greek pedagogy in antiquity. As the center of the rhapsode's repertoire, their recitation was a central part of Greek religious festivals. The book would be spoken or sung all night (modern readings last around 14 hours), with audiences coming and going for parts they particularly enjoyed.

Throughout much of their history, scholars of the written word treated the Iliad and Odyssey as literary poems, and Homer as a writer much like themselves. However, in the late 19th century and the early 20th century, scholars began to question this assumption. Milman Parry, a classical scholar, was intrigued by peculiar features of Homeric style: in particular the stock epithets and the often extensive repetition of words, phrase and even whole chunks of text. He argued that these features were artifacts of oral composition. The poet employs stock phrases because of the ease with which they could be applied to a hexameter line. Taking this theory, Parry travelled in Yugoslavia, studying the local oral poetry. In his research he observed oral poets employing stock phrases and repetition to assist with the challenge of composing a poem orally and improvisationally. Parry's line of inquiry opened up a wider study of oral modes of thought and communication and their evolution under the impact of writing and print by Eric Havelock, Marshall McLuhan, Walter Ong and others.

The relationship of Achilles and Patroclus

The precise nature of the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus has been the subject of some dispute in both the classical period and modern times. In the Iliad, it is clear that the two heroes have a deep and extremely meaningful friendship, but the evidence of a romantic or sexual element is equivocal. Commentators from the classical period to today have tended to interpret the relationship through the lens of their own cultures. Thus, in fifth-century Athens the relationship was commonly interpreted as pederastic, since pederasty was an accepted part of Athenian society. Present day readers are more likely to interpret the two heroes either as non-sexual "war buddies" or as a similarly-aged homosexual couple.

Warfare in the Iliad

Even though Mycene was a maritime power that managed to launch over a thousand ships and Troy at the very least had built the fleet with which Paris took Helen[1] no sea-battle takes place throughout the conflict and Phereclus, the shipbuilder of Troy, fights on foot.[2]

The heroes of the Iliad are dressed in elaborate and well described armor. They ride to the battle field on a chariot, throw a spear to the enemy formation and then dismount, use their other spear and engage in personal combat. Telamonian Ajax's carried a large tower-shaped shield (σάκος) that was used not only to cover him but also his brother:

- Ninth came Teucer, stretching his curved bow.

- He stood beneath the shield of Ajax, son of Telamon.

- As Ajax cautiously pulled his shield aside,

- Teucer would peer out quickly, shoot off an arrow,

- hit someone in the crowd, dropping that soldier

- right where he stood, ending his life—then he'd duck back,

- crouching down by Ajax, like a child beside its mother.

- Ajax would then conceal him with his shining shield.

- (Iliad 8.267–272, translated by Ian Johnston)

Ajax's shield was heavy and difficult to carry. It was thus more suited for defence than offence. His cousin Achilles on the other hand had a large round shield that he used along with his famous spear with great success against the Trojans. Round or eight-sided was the shield of the simple soldier. Unlike the heroes they rarely had a breast-plate and relied exclusively on the shield for defence. They would form very dense formations:

- Just as a man constructs a wall for some high house,

- using well-fitted stones to keep out forceful winds,

- that's how close their helmets and bossed shields lined up,

- shield pressing against shield, helmet against helmet

- man against man. On the bright ridges of the helmets,

- horsehair plumes touched when warriors moved their heads.

- That's how close they were to one another.

- (Iliad 16.213–7, translated by Ian Johnston)

Once Homer actually calls the formation phalanx though the true phalanx formation appears in the 7th century BC.[3] Was this the way that the true Trojan War was fought? Most scholars do not believe so.[4] The chariot was the main weapon in battles of the time, like the battle of Kadesh. There is evidence from the Dendra armor and paintings at the palace of Pylus that the Acheans used two men chariots, with the principal rider armed with a long spear, unlike the Hittite three-men chariots whose riders were armed with shorter spears or the two men chariots armed with arrows used by Egyptians and Syrians. Homer is aware of the use of chariots as a main weapon. Nestor places his charioteers in front of the rest of his troop and tells them:

- In your eagerness to engage the Trojans,

- don't any of you charge ahead of others,

- trusting in your strength and horsemanship.

- And don't lag behind. That will hurt our charge.

- Any man whose chariot confronts an enemy's

- should thrust with his spear at him from there.

- That's the most effective tactic, the way

- men wiped out city strongholds long ago—

- their chests full of that style and spirit.

(Iliad 4.301–309, translated by Ian Johnston)

For Homer this is the old style of fighting, used by the more backward and small kingdoms like Pylus. Nestor describes a battle between Pylus and Elis that took place when he was young that was mainly fought with chariots.[5]

Achilles uses his chariot to advance behind enemy lines and attack the Trojans from behind, thus bringing about a great massacre.[6] Karykas believes that fighting on chariots was generally abandoned by the Acheans a little before the Trojan War, and that Homer describes the battles as they took place.[7] While the opinion that Homer is describing the war as it took place has appeared from time to time among modern Greek writers who were of the military profession,[8] the vast majority of scholars believe Homer is describing how war was waged at the time he lived.

The Iliad in subsequent arts and literature

Subjects from the Trojan War were a favourite among ancient Greek dramatists. Aeschylus' trilogy, the Oresteia, comprising Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides, follows the story of Agamemnon after his return from the war.

William Shakespeare used the plot of the Iliad as a source material for his play Troilus and Cressida, but focused the love story of Troilus, a Trojan prince and a son of Priam, and a Trojan woman Cressida. The play, often considered to be a comedy, reverses traditional views on events of the Trojan War and depicts Achilles as a coward, Ajax as a dull, unthinking mercenary, etc.

Power Metal band Blind Guardian composed a 14 minute song about the Iliad. The song's name is And Then There Was Silence.

The 1954 Broadway musical The Golden Apple by librettist John Treville Latouche and composer Jerome Moross was freely adapted from the Iliad and the Odyssey, re-setting the action to America's Washington state in the years after the Spanish-American War, with events inspired by the Iliad in Act One and events inspired by the Odyssey in Act Two.

Christa Wolf's 1983 novel Kassandra is a critical engagement with the stuff of the Iliad. Wolf's narrator is Cassandra, whose thoughts we hear at the moment just before her murder by Clytemnestra in Sparta. Wolf's narrator presents a feminist's view of the war, and of war in general. Cassandra's story is accompanied by four essays which Wolf delivered as the Frankfurter Poetik-Vorlesungen. The essays present Wolf's concerns as a writer and rewriter of this canonical story and show the genesis of the novel through Wolf's own readings and in a trip she took to Greece.

An epic science fiction adaptation/tribute by acclaimed author Dan Simmons titled Ilium was released in 2003. The novel received a Locus Award for best science fiction novel of 2003.

A loose film adaptation of the Iliad, Troy, was released in 2004, starring Brad Pitt as Achilles, Orlando Bloom as Paris, Eric Bana as Hector, Sean Bean as Odysseus and Brian Cox as Agamemnon. It was directed by German-born Wolfgang Petersen. The movie only loosely resembles the Homeric version, with the supernatural elements of the story were deliberately expunged, except for one scene that includes Achilles' sea nymph mother, Thetis (although her supernatural nature is never specifically stated, and she is aged as though human).

Though the film received mixed reviews, it was a commercial success, particularly in international sales. It grossed $133 million in the United States and $497 million worldwide, placing it in the 50 top-grossing movies of all time.

A number of comic series have re-told the legend of the Trojan War. The most inclusive may be Age of Bronze, a comprehensive retelling by writer/artist Eric Shanower that incorporates a broad spectrum of literary traditions and archaeological findings. Started in 1999, it is projected to number seven volumes.

Translations into English

The Iliad has been translated into English for centuries. George Chapman's 16th century translation was praised by John Keats in his sonnet, On First Looking into Chapman's Homer. Alexander Pope's translation into rhymed pentameter was published in 1713. William Cowper's 1791 version in forceful Miltonic blank verse is highly regarded. In his lectures On Translating Homer Matthew Arnold commented on the problems of translating the Iliad and on the major translations available in 1861. In 1870 the American poet William Cullen Bryant published a "simple, faithful" (Van Wyck Brooks) version in blank verse.

There are several twentieth century English translations. Richmond Lattimore's version attempts to reproduce, line for line, the rhythm and phrasing of the original poem. Robert Fitzgerald has striven to situate the Iliad in the musical forms of English poetry. Robert Fagles and Stanley Lombardo both follow the Greek closely but are bolder in adding dramatic significance to conventional and formulaic Homeric language. Lombardo has chosen an American idiom that is much more colloquial than the other translations.

Partial List of English translations

This is a partial list of translations into English of Homer's Iliad. For a more complete list, see English translations of Homer.

- George Chapman, 1598 and 1615 - verse

- John Ogilby, 1660

- Thomas Hobbes, 1676 - verse: full text

- John Ozell, William Broome and William Oldisworth, 1712

- Alexander Pope, 1713 - verse: full text

- James Macpherson, 1773

- William Cowper, 1791: full text

- Lord Derby, 1864 - verse: full text

- William Cullen Bryant, 1870

- Walter Leaf, Andrew Lang and Ernest Myers, 1873 - prose: full text

- Samuel Butler, 1898 - prose: full text

- A.T. Murray, 1924

- Alexander Falconer, 1933

- Sir William Marris, 1934 - verse

- E.V. Rieu, 1950 - prose

- Alston Chase and William G. Perry, 1950 - prose

- Richmond Lattimore, 1951 - verse

- Ennis Rees, 1963 - verse

- W.H.D. Rouse, 1966 - prose

- Robert Fitzgerald, 1974

- Martin Hammond, 1987

- Robert Fagles, 1990

- Stanley Lombardo, 1997

- Ian Johnston, 2002 - verse: full text

See also

References

- Budimir, Milan (1940). On the Iliad and Its Poet.

- Mueller, Martin (1984). The Iliad. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-800027-2.

- Nagy, Gregory (1979). The Best of the Achaeans. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2388-9.

- Powell, Barry B. (2004). Homer. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. 978-1-4051-5325-6.

- Seaford, Richard (1994). Reciprocity and Ritual. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815036-9.

- West, Martin (1997). The East Face of Helicon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815221-3.

- ^ Iliad 3.45–50

- ^ Iliad 5.59–65

- ^ Iliad 6.6

- ^ Tomas Cahill, Sailing the Wine Dark Sea, Why the Greeks Matter, New York 2003

- ^ Iliad Λ 670–760

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

PKwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Karykaswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Konstaswas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

External links

- Iliad in Ancient Greek: from the Perseus Project (PP), with the Murray and Butler translations and hyperlinks to mythological and grammatical commentary; via the Chicago Homer, with the Lattimore translation and markup indicating formulaic repetitions

- Links to translations freely available online are included in the list above.

- The Iliad: A Study Guide

- Classical images illustrating the Iliad. Repertory of outstanding painted vases, wall paintings and other ancient iconography of the War of Troy.