Tláloc

- For the fictional character from the Legends of Dune books, see Titan (Dune)#Tlaloc.

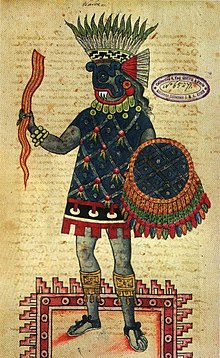

Tlaloc (Template:Lang-nci IPA: ['tɬaː.loːk]) was an important deity in Aztec religion, a god of rain, fertility, and water. He was a beneficent god who gave life and sustenance, but he was also feared for his ability to send hail, thunder and lightning, and for being the lord of the powerful element of water. In Aztec iconography he is normally depicted with goggle eyes and fangs. He was associated with caves, springs and mountains. He is known for having demanded child sacrifices.[1]

In Aztec cosmology, the four corners of the universe are marked by "the four Tlalocs" (Nahuatl: Tlālōquê IPA: [tɬaː.'loː.keʔ]) which both hold up the sky and functions as the frame for the passing of time. Tlaloc was the patron of the Calendar day Mazatl and of the trecena of Ce Quiyahuitl (1 Rain). In Aztec mythology, Tlaloc was the lord of the third sun which was destroyed by fire.

In the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan, one of the two shrines on top of the Great Temple was dedicated to Tlaloc. The High Priest who was in charge of the Tlaloc shrine was called "Quetzalcoatl Tlaloc Tlamacazqui". However the most important site of worship to Tlaloc was on the peak of Mount Tlaloc, a 4100 metres high mountain on the eastern rim of the Valley of Mexico. Here the Aztec ruler came and conducted important ceremonies once a year, and throughout the year pilgrims offered precious stones and figures at the shrine.

In Coatlinchan a colossal statue weighing 168 tons was found that was thought to represent Tlaloc. Some scholars believe that the statue may not have been Tlaloc at all but his sister or some other female deity. This statue was relocated to the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City in 1964. [2]

Name

Tlaloc was also associated with the watery world of the dead, and with the earth. His name is thought to be derived from the Nahuatl word tlālli "earth", and its meaning has been interpreted as "path beneath the earth", "long cave" or "he who is made of earth".[3] J. Richard Andrews interprets it as "one that lies on the land", identifying Tlaloc as a cloud resting on the mountaintops.[4] Other names of Tlaloc were Tlamacazqui ('Giver')[5] and Xoxouhqui ('Green One')[6]; and (among the contemporary Nahua of Veracruz) Chaneco[7].

Mythology

Tlaloc was first married to Xochiquetzal, a goddess of flowers, but then Tezcatlipoca kidnapped her. He later married the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue, "She of the Jade Skirt". In Aztec mythic cosmography, Tlaloc ruled the fourth layer of the 'Upper World", or heavens, which is called Tlalocan ("place of Tlaloc") in several Aztec codices, such as the Vaticanus A and Florentine codices. Described as a place of unending Springtime and a paradise of green plants, Tlalocan was the destination in the afterlife for those who died violently from phenomena associated with water, such as by lightning, drowning and water-borne diseases (Miller and Taube, 1993).

With Chalchiuhtlicue, he was the father of Tecciztecatl. He had an older sister named Huixtocihuatl. He ruled over the third of the five worlds in Aztec belief. In Salvadoran mythology, he was also the father of Cipitio.

Rites and Rituals

Those who died in water or weather related deaths such as drowning, lightning and water-borne diseases (Leprosy, dropsy, scabies and gout) were thought to pass on to Tlalocan when they died, as were people of stunted growth (as their short stature was seen as a connection to the Tlaloque). The Tlalocan-bound dead were not cremated as was standard custom, but instead were buried in the earth with seeds planted in their faces and blue paint covering their foreheads. Their bodies were dressed in paper and a digging stick for planting put in their hands.

The second shrine on top of the main pyramid at Tenochtitlan was dedicated to Tlaloc. Both his shrine, and Huitzilopochtli’s next to it, faced west. Sacrifices and rites took place in these temples. The Aztecs believed Tlaloc resided in mountain caves, thus his shrine in Tenochtitlan’s pyramid was called ’mountain abode’. Many rich offerings were regularly placed before it, especially those linked to water such as jade, shells and sand. Mount Tlaloc, the jewel in the crown of Tlaloc’s places of worship, was situated directly east of the pyramid. It was exactly 44 miles away and a long road connected the two places of worship. On it was a shrine containing stone images of the mountain itself and other neighbouring peaks. The shrine was called Tlalocan, in reference to the paradise. Also to be found inside its walls were four pitchers containing water. Each pitcher would bring a different fate if used on crops: one would bring forth a good harvest, another would rot it, the third would dry the harvest out and the final one would freeze it. Sacrifices that took place here were thought to favor early rains.

The ’Atlcahualo’ was celebrated from the 12th of February until the 3rd of March. Dedicated to the Tlaloque, this veintena involved the sacrifice of many children on sacred mountaintops. The children were beautifully adorned, dressed in the style of Tlaloc and the Tlaloque. On litters strewn with flowers and feathers; surrounded by dancers, they were transported to a shrine and their hearts would be pulled out by priests. If, on the way to the shrine, these children cried their tears were viewed as signs of imminent and abundant rains. Children who did not weep could have their fingernails torn off in order to achieve this effect. Every Atlcahualo festival, seven children were sacrificed in and around Lake Tetzcoco in the Aztec capital. They were either slaves or the second born children of nobles.

Similarly the festival of Tozoztontli (24th March - 12th April) involved more child sacrifice. Additionally, offerings were made in caves. The flayed skins of sacrificial victims that had been worn by priests for the last twenty days were taken off and placed in these dark, magical caverns.

The winter ’veintena’ of Atemoztli (9th December- 28th December) was also dedicated to the Tlaloque. This period preceded an important rainy season and so statues of them were made out of amaranth dough. Their teeth were pumpkin seeds and their eyes, beans. Once these statues were adorned, offered copal and fine scents and prayed to, food was presented before them.

Afterwards their doughy chests were opened, their ’hearts’ taken out and, finally, their bodies cut up and eaten. The ornaments with which they had been adorned were taken and burned in peoples’ patios. On the final day of the ’veintena’ people celebrated and held banquets.[8]

Related gods

Archaeological evidence indicates Tlaloc was worshipped in Mesoamerica before the Aztecs even settled there in 13th century AD. He was a prominent god in Teotihuacan at least 800 years before the Aztecs. [9] This has led to mesoamerican goggle-eyed raingods being referred to generically as "Tlaloc" although in some cases it is unknown what they were called in these cultures, and in other cases we know that he was called by a different name (e.g. the Mayan version was known as Chaac and the Zapotec deity Cocijo).

Notes

- ^ http://www.conaculta.gob.mx/saladeprensa/2002/25mar/tlaloc.htm – article in Spanish

- ^ Time Life Lost Civilizations series:Aztecs: Reign of Blood and Splendor (1992) p.45-47

- ^ Lòpez Austin (1997) p. 214

- ^ Andrews (2003): p. 596.

- ^ Lòpez Austin (1997) p. 209, citing Sahagún, lib. 1, cap. 4

- ^ Lòpez Austin (1997) p. 209, citing the Florentine Codex lib. 6, cap. 8

- ^ Lòpez Austin (1997) p. 214, citing Guido Münch Galindo : Etnología del Istmo Veracruzano. México : UNAM, 1983. p. 160

- ^ http://www.mexicolore.co.uk/acrobats/319_1.pdf

- ^ http://www.mexicolore.co.uk/acrobats/319_1.pdf

References

- Andrews, J. Richard (2003). Introduction to Classical Nahuatl (revised edition ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3452-6. OCLC 50090230.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Iwaniszewski, Stanislaw (1994). "Archaeology and Archaeoastronomy of Mount Tlaloc, Mexico: A Reconsideration". Latin American Antiquity. 5 (2). Washington, DC: Society for American Archaeology: pp.158–176. doi:10.2307/971561. ISSN 1045-6635. OCLC 54395676.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - López Austin, Alfredo (1997). Tamoanchan, Tlalocan: Places of Mist. Mesoamerican Worlds series. translated by Bernard R. Ortiz de Montellano and Thelma Ortiz de Montellano. Niwot: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-445-1. OCLC 36178551.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Miller, Mary (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 5 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Townsend, Richard F. (2000). The Aztecs (2nd edition, revised ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28132-7. OCLC 43337963.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

![]() Media related to Tlaloc at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tlaloc at Wikimedia Commons