Dubrovnik

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2008) |

This template is a customized wrapper for {{[[Template:{{{1}}}|{{{1}}}]]}}. Any field from {{[[Template:{{{1}}}|{{{1}}}]]}} can work so long as it is added to this template first. Questions? Just ask here or over at [[Template talk:{{{1}}}]]. |

|

Dubrovnik | |

|---|---|

The walled city of Dubrovnik | |

| Nickname: Pearl of the Adriatic | |

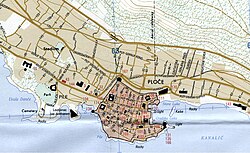

1995 map of Dubrovnik | |

| Country | Croatia |

| County | Dubrovnik-Neretva county |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Dubravka Šuica (CDU) |

| Area | |

• Total | 21.35 km2 (8.24 sq mi) |

| Population (2001) | |

• Total | 43,770 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 20000 |

| Area code | 020 |

| Licence plate | DU |

|-

|

|-

|

|-

|

|-

|

|-

|

|-

|

|}

Dubrovnik ([pronunciation?], also known as "the Pearl of the Adriatic"[1]) is a city on the Adriatic Sea coast in the extreme south of Croatia, positioned at the terminal end of the Isthmus of Dubrovnik. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations on the Adriatic, a seaport and the centre of Dubrovnik-Neretva county. Its population was 43,770 in 2001[2] down from 49,728 in 1991.[3] In the 2001 census, 88.39% of its citizens declared themselves as Croats.

In 1979, the city of Dubrovnik joined the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites.

The prosperity of the city of Dubrovnik has always been based on maritime trade. In the Middle Ages, as the Republic of Dubrovnik, it became the only eastern Adriatic city-state to rival Venice. Supported by its wealth and skilled diplomacy, the city achieved a remarkable level of development, particularly during the 15th and 16th centuries. Dubrovnik was one of the centres of the development of primarily the Croatian language and literature, home to many notable poets, playwrights, painters, mathematicians, physicists and other scholars.

Name

In Croatian, and all other Slavic languages, the city is known as Dubrovnik; in Italian as Ragusa, in Greek as Raiyia (Ραυγια) or Ragousa (Ραγουσα); Albanian in 17th century sources lists the city as Rush.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

The Slavic toponym Dubrovnik originates from the Proto-Slavic term for an oak forest *dǫbrava or *dǫbrova (dubrava in archaic and literary Croatian), which was abundantly present in the hills north of the walled city of Dubrovnik by the end of the 11th century.

The current name was officially adopted in 1909, when the city was under Austro-Hungarian rule. [citation needed]

History

From the foundation to the end of the Republic

Historical lore indicates that Dubrovnik was founded in the 7th century on a rocky island named Laus, which provided shelter for Croatian refugees from the nearby city of Cavtat. Some time later a settlement of Slavic people grew at the foot of the forested Srđ hill. This settlement gives to the city its Slavic name "Dubrovnik".

The strip of wetland between Dubrovnik and Dubrava was reclaimed in the 12th century, unifying the city around the newly-made plaza (today Placa). The plaza was paved in 1468 and reconstructed after the earthquake of 1667. The city was fortified and two harbours were built on each side of the isthmus.

Another theory appeared recently, based on new archaeological excavations. New findings (a chapel and parts of the city walls) are dated to 5th century, and that contradicts the traditional theory. The size of the old chapel clearly indicates that there was quite large settlement at that time. There is increasing support in the scientific community for the theory that major construction of Dubrovnik took place during B.C. years. This "Greek theory" has been boosted by recent findings of numerous Greek artifacts during excavations in the Port of Dubrovnik. Also, drilling below main city road has shown that there is natural sand, which contradicts the theory of Laus (Lausa) island.

Dr. Antun Ničetić in his book (Povijest dubrovačke luke - History of Port of Dubrovnik) expounds on the theory that Dubrovnik was established by Greek sailors. A key element in this theory is the fact that ships in ancient times travelled about 45-50 nautical miles per day, and required a sandy shore to pull out of water for the rest period during the night. The ideal rest site would have fresh water source in the vicinity. Dubrovnik has both, and is situated almost halfway between two known Greek settlements Budva and Korčula (95 NM is the distance between them).

From its establishment in the 7th century, the town was under the protection of the Byzantine Empire. After the Crusades, Dubrovnik came under the sovereignty of Venice (1205–1358), and by the Peace Treaty of Zadar in 1358, it became part of the Hungaro-Croatian reign.

Between the 14th century and 1808 Dubrovnik ruled itself as a free state. The Republic had its peak in the 15th and 16th centuries, when its thalassocracy rivaled that of the Republic of Venice and other Italian maritime republics.

The Republic of Dubrovnik received its own Statutes as early as 1272, statutes which, among other things, codified Roman practice and local customs. The Statutes included prescriptions for town planning and the regulation of quarantine (for hygienic reasons). The Republic was very inventive regarding laws and institutions that were developed very early:

- Medical service was introduced in 1301

- The first pharmacy (still working) was opened in 1317

- A refuge for old people was opened in 1347

- The first quarantine hospital (Lazarete) was opened in 1377

- Slave trading was abolished in 1418

- The orphanage was opened in 1432

- The water supply system (20 kilometers) was constructed in 1436

The city was ruled by aristocracy that formed two city councils. As usual for the time, they maintained a strict system of social classes. The republic abolished the slave trade early in the 15th century and valued liberty highly. The city successfully balanced its sovereignty between the interests of Venice and the Ottoman Empire for centuries.

The economic wealth of the Republic was partially the result of the land it developed, but especially of the seafaring trade it did. With the help of skilled diplomacy, Dubrovnik's merchants traveled lands freely, and on the sea the city had a huge fleet of merchant ships (argosy) that traveled all over the world. From these travels they founded some settlements, from India to America, and brought parts of their culture and vegetation home with them. One of the keys to success was not conquering, but trading and sailing under a white flag with the word freedom (Template:Lang-la) prominently featured on it. That flag was adopted when slave trading was abolished in 1418.

Many Conversos (Marranos) — Jews from Spain and Portugal — were attracted to the city. In May, 1544, a ship landed there filled exclusively with Portuguese refugees, as Balthasar de Faria reported to King John. During this time there worked in the city one of the most famous cannon and bell founders of his time: Ivan Rabljanin (Magister Johannes Baptista Arbensis de la Tolle).

The Republic gradually declined after a crisis of Mediterranean shipping — and especially a catastrophic earthquake in 1667 that killed over 5000 citizens, including the Rector, leveling most of the public buildings — ruined the well-being of the Republic. In 1699 the Republic sold two patches of its territory to the Ottomans in order to avoid terrestrial borderline, with advancing Venetian forces. Today this strip of land belongs to Bosnia and Herzegovina and is its only direct access to the Adriatic.

In 1806 the city surrendered to French forces, as that was the only way to cut a month's long siege by the Russian-Montenegrin fleets (during which 3000 cannonballs fell on the city). At first Napoleon demanded only free passage for his troops, promising not to occupy the territory and stressing that the French were friends of the Ragusans. Later, however, French forces blockaded the harbours, forcing the government to give in and let French troops enter the city. On this day, all flags and coats of arms above the city walls were painted black as a sign of grief. In 1808, Marshal Marmont abolished the republic and integrated its territory into the Illyrian provinces.

Austrian rule

When the Habsburg Empire gained these provinces after the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the new imperial authorities installed a bureaucratic administration, which retained the essential framework of the Italian-speaking system. It introduced a series of modifications intended to centralize, albeit slowly, the bureaucratic, tax, religious, educational, and trade structures. Unfortunately for the local residents, these centralization strategies, which were intended to stimulate the economy, largely failed. And once the personal, political and economic trauma of the Napoleonic Wars had been overcome, new movements began to form in the region, calling for a political reorganization of the Adriatic along national lines. [citation needed]

The combination of these two forces—a flawed Habsburg administrative system and new national movements claiming ethnicity as the founding block towards a community—created a particularly perplexing problem; for Dalmatia was a province ruled by the German-speaking, centralizing Habsburg monarchy, with Italian-speaking elites that dominated a general population consisting of a Croatian, Catholic Slav majority and strong Serb Orthodox minority. [citation needed]

In 1815, the former Ragusan Government, i.e. its noble assembly, met for the last time in the ljetnikovac in Mokošica. Once again heavy efforts were undertaken to reestablish the Republic however this time it was all in vain. After fall of the Republic most of the aristocracy died out or emigrated overseas. Others were recognized by Austrian Empire.

In 1832, Baron Sigismondo Ghetaldi-Gondola (*1795 +1860) was elected podestá of Ragusa, he served for 13 years, the Austrian government granted with the title of "Baron".

Count Raphael Pozza (Rafo Pucic) (*1828 +1890), Dr. Jur., was elected for first time Podestà of Ragusa in the year 1869 after this was reelected in 1872, 1875, 1882, 1884) and elected two times into the Dalmatian Council, 1870, 1876. The victory of the Nationalist in Split (Spalato) in 1882 had a strong echo in the areas of Korkula and Dubrovnik. It was greeted by the mayor (podestá) of Dubrovnik Raphael Pozza, the National Reading Club of Dubrovnik, the Workers Association of Dubrovnik and the review "Slovinac"; by the communities of Kuna and Orebici, the latter one getting the nationalist govermment even before Split (Spalato).

In 1848, Croatian Assembly (Sabor) published People's Requests in which they requested among other things abolition of serfdom and the unification of Dalmatia with rest of Croatian lands (primarily with Austro-Hungarian Kingdom of Croatia). Dubrovnik municipality was the most outspoken of all Dalmatian communes in its support for unification with Croatia. A letter was sent to Zagreb with pledges to work on this idea. In 1849, Dubrovnik continued to lead Dalmatian cities in the struggle for unification. A large-scale campaign was launched in the local paper L'Avvenire (The Future) based on a clearly formulated programme: the federal system for Habsburg territories, inclusion of Dalmatia into united Croatia and Slavic brotherhood.

In the same year, first issue of the Dubrovnik almanac appeared, Flower of the National Literature (Dubrovnik, cvijet narodnog knjizevstva), in which Petar Preradović published his noted poem "To Dubrovnik". The Emperor Franz Joseph brought the so-called Imposed Constitution which prohibited unification of Dalmatia and Croatia and also any further political activity with this end in view. The political struggle of Dubrovnik to be united with Croatia, which was intense throughout 1848 and 1849, did not succeed at that time.

In 1861, the Dalmatian Assembly met for the first time, with representatives from Ragusa. Representatives of Cattaro (now Kotor) came to join the struggle for unification with Croatia. The citizens of Ragusa gave them a festive welcome, flying Croatian flags from ramparts, and exhibiting slogan: Ragusa with Cattaro. The people of Cattaro elected a delegation to go to Vienna; Ragusa nominated Niko Pucić (National Party). Niko Pucić went to Vienna to demand not only the unification of Dalmatia with Croatia, but also the unification of all Croatian territories under one common Assembly.

Austrian rule and Austro-Hungarian rule which followed lasted for more than a century and were typified by the motto of the world powers of that time: Divide et impera (Divide and rule). Austrian policy of denationalizing the Dalmatian coasts and favoring the immigrant Italian minority left its mark in the political division of the population as best expressed in the political parties: the Croatian People's Party and the Autonomous Party. [citation needed]

In 1889, Serbian Catholics political circle in Dubrovnik supported Baron Francesco Ghetaldi-Gondola, candidate of Autonomous Party, vs the candidate of Popular Party Vlaho de Giulli, in 1890 election to Dalmatian Diet.[10] Following year during the local government election, Autonomous Party with Serbian Party obtain the municipal reelection with Frano Gondola, who died in charge 1899, the aliance won again the election 27 May 1894. Francesco Ghetaldi-Gondola was founded the Societa Philately in 4 December 1890.

In 1893, the minister of the city, Baron Francesco Ghetaldi-Gondola, opened the monument for Ivan Gundulić in Piazza Gundulić (Gondola).

1921–1991

With fall of Austria-Hungary in 1918, the city was incorporated into the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia). The name of the city was officially changed from Ragusa to Dubrovnik.

In 1921 Pero Cingrija died (born 1837), politician and one of the leaders of the People's Party in Dalmatia. It was thanks to his efforts that the People's Party and the Party of Right were fused into one Croatian Party in 1905

In World War II, Dubrovnik became part of the Nazi puppet Independent State of Croatia, occupied by an Italian army first, and by a German army after September 1943. In October 1944 Tito's partisans entered Dubrovnik, that became consequently part of Communist Yugoslavia. Soon after their arrival into the city, Partisans sentenced approximately 78 citizens to death without trial, including a Catholic priest.[11]

Break-up of Yugoslavia

In 1991 Croatia and Slovenia, which at that time were republics within Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, declared their independence. At that event, Socialist Republic of Croatia was renamed Republic of Croatia.

Despite demilitarization of the old town in early 1970s in an attempt to prevent it from ever becoming a casualty of war, following Croatia's independence in 1991, Serbian-Montenegrin remains of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) attacked the city. The regime in Montenegro led by Momir Bulatović, which was installed by and loyal to the Serbian government led by Slobodan Milošević, declared that Dubrovnik would not be permitted to remain in Croatia because they claimed it was historically part of Montenegro.[12] This was in spite of the large Croat majority in the city and that very few Montenegrins resided there, though Serbs accounted for six percent of the population.[12] Many consider the claims by the Bulatović government, as being part of Serbian President Milošević's plan to deliver his nationalist supporters the Greater Serbia they desired as Yugoslavia collapsed.[12]

On October 1, 1991 Dubrovnik was attacked by JNA with a siege of Dubrovnik that lasted for seven months. Heaviest artillery attack happened on December 6 with 19 people killed and 60 wounded. Total casualties in the conflict according to Croatian Red Cross were 114 killed civilians, among them celebrated poet Milan Milisić. In May 1992 the Croatian Army liberated Dubrovnik and its surroundings, but the danger of sudden attacks by the JNA lasted for another three years. [citation needed]

Following the end of the war, damage caused by the shelling of the Old Town was repaired. Adhering to UNESCO guidelines, repairs were performed in the original style. As of 2005[update], most damage had been repaired. The inflicted damage can be seen on a chart near the city gate, showing all artillery hits during the siege. ICTY indictments were issued for JNA generals and officers involved in the bombing.

General Pavle Strugar, who was coordinating the attack on the city, was sentenced to an eight year prison term by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia for his role in the attack of the city.

The 1996 Croatia USAF CT-43 crash killed everyone on a United States Air Force jet with VIP passengers.

Video of the attack on Dubrovnik

Today

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, iv |

| Reference | 95 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Extensions | 1994 |

| Endangered | 1991-1998 |

The annual Dubrovnik Summer Festival is a cultural event when keys of the city are given to artists who entertain Dubrovnik's population and their guests for entire month with live plays, concerts, and games.

Ivan Gundulić, a 17th century Croatian writer, predicted the downfall of the great Turkish Empire in his great poem Osman.

The Dubrovnik Summer Festival has been awarded its first Gold International Trophy for Quality (2007) by the Editorial Office in collaboration with the Trade Leaders Club.

February 3 is the feast of Sveti Vlaho (Saint Blaise), who is the city's patron saint. Every year the city of Dubrovnik celebrates the holiday with Mass, parades, and festivities that last for several days.[13]

Dubrovnik and its surroundings with numerous islands have a lot to offer in touristic activities for younger generations. Also popular are climbing on steep hills, hiking through the Mediterranean nature, and swimming in the clean, transparent sea.

The Old Town of Dubrovnik is depicted on the reverse of the Croatian 50 kuna banknote, issued in 1993 and 2002.[14]

Heritage

The patron saint of the city is Sveti Vlaho (Saint Blaise), whose statues are seen around the city. He has an importance similar to that of St. Mark the Evangelist to Venice. The city's cathedral is named after Saint Blaise. The city boasts of many old buildings, such as the Arboretum Trsteno, the oldest arboretum in the world, dating back to before 1492. Also, the third oldest European pharmacy is located in the city, which dates back to 1317 (and is the only one still in operation today). It is located at Little Brothers church in Dubrovnik.[15]

In history, many Conversos (Marranos) were attracted to Dubrovnik, formerly a considerable seaport. In May, 1544, a ship landed there filled exclusively with Portuguese refugees, as Balthasar de Faria reported to King John. Another admirer of Dubrovnik, George Bernard Shaw, visited the city in 1929 and said: "If you want to see heaven on earth, come to Dubrovnik."

In the bay of Dubrovnik is the 72-hectare wooded island of Lokrum, where according to legend, Richard the Lionheart was cast ashore after being shipwrecked in 1192. The island includes a fortress, botanical garden, monastery and naturist beach.

Dubrovnik has also been mentioned in popular film and theater. In the film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea with Michael Caine, one of the characters said to have been dreaming of fairy from Dubrovnik (motive known from local legends and literature).

Important monuments

Few of Dubrovnik's Renaissance buildings survived the earthquake of 1667 but fortunately enough remain to give an idea of the city's architectural heritage.[16] The finest Renaissance highlight is the Sponza Palace which dates from the 16th century and is currently used to house the National Archives.[17] The Rectors Palace is a Gothic-Renaissance structure that displays finely-carved capitals and an ornate staircase. It now houses a museum.[18] Its façade is depicted on the reverse of the Croatian 50 kuna banknote, issued in 1993 and 2002.[14] The St Saviour Church is another remnant of the Renaissance period, next to the much-visited Franciscan Monastery.[19] The Franciscan monastery's library possesses 30,000 volumes, 22 incunabula, 1,500 valuable handwritten documents. Exhibits include a 15th century silver-gilt cross and silver thurible, an 18th century crucifix from Jerusalem, a martyrology (1541) by Bemardin Gucetić and illuminated Psalters.[20]

Dubrovnik's most beloved church is St Blaise's church, built in the 18th century in honor of Dubrovnik's patron saint. Dubrovnik's baroque Cathedral was built in the 18th century and houses an impressive Treasury with relics of Saint Blaise. The city's Dominican Monastery resembles a fortress on the outside but the interior contains an art museum and a Gothic-Romanesque church.[21] A special treasure of the Dominican monastery is its library with over 220 incunabula, numerous illustrated manuscripts, a rich archive with precious manuscripts and documents and an extensive art collection. [22]

A feature of Dubrovnik is its walls that run 2 km around the city. The walls run from four to six metres thick on the landward side but are much thinner on the seaward side. The system of turrets and towers were intended to protect the vulnerable city.[23]

Transport

Dubrovnik has an international airport of its own. It is located approximately 20 km (12 mi) from Dubrovnik city center, near Čilipi. Buses connect the airport with the Dubrovnik bus station. In addition, a network of modern, local buses connects all Dubrovnik neighborhoods running frequently from dawn to midnight.

The A1 highway, in use between Zagreb and Ravča, is planned to be extended all the way to Dubrovnik. The highway will cross the Pelješac Bridge which is currently under construction. An alternative plan proposes the highway running from Neum through Bosnia and Herzegovina and an expressway continuing to Dubrovnik. This plan has fallen out of favor, though.

Education

Dubrovnik has a number of educational institutions. These include Dubrovnik International University, the University of Dubrovnik, a Nautical College, a Tourist College, a University Centre for Postgraduate Studies of the University of Zagreb, American College of Management and Technology, and an Institute of History of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Climate

The climate along the Dubrovnik Region is a typical Mediterranean one, with mild, rainy winters and hot and dry summers. However, it is perhaps distinct from other Mediterranean climates because of the unusual winds and frequency of thunderstorms. The Bura wind blows uncomfortably cold gusts down the Adriatic coast between October and April, and thundery conditions are common all the year round, even in summer, when they interrupt the warm, sunny days. The air temperatures can slightly vary, depending on the area or region. Typically, in July and August daytime maximum temperatures reach 29°C, and at night drop to around 21°C. More comfortable, perhaps, is the climate in Spring and Autumn when maximum temperatures are typically between 20°C and 28°C.

| Month | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg high °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) | 12.3 (54.1) | 14.4 (57.9) | 16.9 (62.4) | 21.3 (70.3) | 25.2 (77.4) | 28.3 (82.9) | 28.7 (83.7) | 25.4 (77.7) | 21.4 (70.5) | 16.6 (61.9) | 13.3 (55.9) | |

| Avg low °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) | 6.4 (43.5) | 8.5 (47.3) | 10.9 (51.6) | 15.2 (59.4) | 18.8 (65.8) | 21.5 (70.7) | 21.7 (71.1) | 18.7 (65.7) | 15.2 (59.4) | 10.8 (51.4) | 7.8 (46.0) | |

| Source: Worldweather.org | |||||||||||||

- Air temperature

- average annual

- 16.4°C (61.5°F)

- average of coldest period = January

- 9 °C (48.2 °F)

- average of warmest period = August

- 24.9 °C (76.8 °F)

- Sea temperature

- average May – September

- 17.9 °C - 23.8 °C (64.2 °F - 74.8 °F)

- Salinity*

- approximately 38 ‰ (parts per thousand)

- Precipitation

- average annual

- 1,020.8 mm

- average annual rain days

- 109.2

- Sunshine

- average annual

- 2629 h

- average daily hours

- 7.2 h

Notable people from Dubrovnik

- Franco Sacchetti (1332-1400), Italian poet

- Marin Držić (1508-1567), Croatian playwright and prose writer

- Cvijeta Zuzorić (c. 1552 - c. 1600), Croatian poetess

- Dinko Zlatarić (1558-1613), Croatian poet and translator

- Marin Getaldić (1568–1626), Croatian scientist

- Ivan Gundulić (1589-1638) Croatian poet

- Ruđer Bošković (1711-1787), Croatian scientist, diplomat and poet

- Vlaho Getaldić (1788-1872), politician, noble, poet

- Niko Pucić (1820-1883) - Croatian politician and nobleman

- Medo Pucić (1821-1882) - Croatian writer, politician and nobleman

- Federico Seismit-Doda (1825-1893), Italian politician

- Frano Getaldić-Gundulić (1833-1899) - soldier, statesman, nobleman, Knight of Malta

- Pero Budmani (1835-1914), linguist

- Vlaho Bukovac (1855-1922),Croatian painter

- Ivo Vojnović (1857-1929), Croatian writer

- Antun Fabris (1864-1904), Croatian journalist and politician

- Frano Supilo (1870-1917), Croatian politician and journalist

- Blagoje Bersa (1873-1934),Croatian musician

- Eduard Miloslavić (1884-1952), scientist

- Branko Bauer (born 1921), Croatian film director

- Ottavio Missoni (born 1921), Italian fashion designer

- Tereza Kesovija (born 1938), Croatian singer

- Božo Vuletić (born 1958), Croatian waterpolo player, Olympic gold medalist

- Goran Sukno (born 1959), Croatian waterpolo player, Olympic gold medalist

- Veselin Đuho (born 1960), Croatian waterpolo player and coach, double Olympic gold medalist

- Sanja Jovanović (born 1986), Olympic swimmer

International relations

Twin towns - Sister cities

Dubrovnik is twinned with:

Graz, Austria, since 1994.

Graz, Austria, since 1994. Bad Homburg, Germany, since 2002.

Bad Homburg, Germany, since 2002. Helsingborg, Sweden, since 1998.

Helsingborg, Sweden, since 1998. Vukovar, Croatia, since 1993.

Vukovar, Croatia, since 1993. Monterey, California, USA, since 2007.

Monterey, California, USA, since 2007. Sandnes, Norway

Sandnes, Norway

Images

Panorama

Gallery

-

Walls of Dubrovnik

-

Massive walls

-

Lovrijenac Tower

-

Onuphrius's Fountain and the Church of Saint Saviour

-

The Roland statue, symbol of a free city

-

Church of St. Blasius by night

-

Dubrovnik as seen from its wall

See also

References

- ^ What Lord Byron called it

- ^ City of Dubrovnik. Dubrovnik.hr. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- ^ Dubrovnik. History.com Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- ^ Template:It iconhttp://edu.let.unicas.it/bmb/sigle/bibsc_d.htm

- ^ Template:It iconhttp://www.crociereonline.net/destinazioni/dubrovnik.htm

- ^ Template:It icon http://www.indalmazia.com/citta_dubrovnik.htm

- ^ Template:It iconhttp://www.dubrovnik-guide.net/homeIT.htm

- ^ Template:It iconhttp://www.informagiovani-italia.com/dubrovnik.htm

- ^ Template:It iconhttp://www.croaziainfo.it/Dubrovnik.html

- ^ "Trudna tożsamość: problemy ... - Búsqueda de libros de Google". Books.google.cl. 2007-09-20. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ "Nakon ulaska partizana u Dubrovnik u listopadu 1944.: Partizani pogubili hrvatske antifašiste | Izdvojeno | Glas Koncila". Glas-koncila.hr. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ^ a b c Srđa Pavlović. "Pavlovic: The Siege of Dubrovnik". Yorku.ca. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ^ Dubrovnik news

- ^ a b Croatian National Bank. Features of Kuna Banknotes: 50 kuna (1993 issue) & 50 kuna (2002 issue). – Retrieved on 30 March 2009.

- ^ Dubrovnik Online, monuments in Dubrovnik

- ^ Croatia Traveller, Dubrovnik History

- ^ "Dubrovnik - Sponza Palace". Dubrovnikcity.com. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ "Dubrovnik: the Rector's Palace". Dubrovnik-guide.net. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ "Franciscan Friary - Dubrovnik, Croatia". Sacred-destinations.com. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ "Dubrovnik Online, monuments in Dubrovnik". Dubrovnik-online.com. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Croatia Traveller, Dominican Monastery

- ^ "Dubrovnik Dominican monastery". Dubrovnik-guide.net. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Croatia Traveller, Dubrovnik

Further reading

- Harris, Robin. Dubrovnik, A History. London: Saqi Books, 2003. ISBN 0-86356-332-5

- Kremenjaš-Daničić, Adriana (Editor-in-Chief): Roland's European Paths. Dubrovnik: Europski dom Dubrovnik, 2006. ISBN 953-95338-0-5