Bulgarians

| Part of a series on |

| Bulgarians Българи |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| By country |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Other |

The Bulgarians (Template:Lang-bg, bulgari) are european people, assumed to be South Slavic[48], although genetical research prooves very little slavic influence (see Genetic origin), generally associated with the Republic of Bulgaria and the Bulgarian language. Emigration has resulted in Bulgarian minorities or immigrant communities in a number of other countries.

Ethnogenesis

The modern Bulgarians have descended from three main ethnic groups which mixed in the Balkans during the 6th - 10th century: local tribes, known as the Thracians; Slavic invaders, who gave their language to the modern Bulgarians; and the Bulgars, from whom the ethnonym and the early statehood were inherited.

The ethnic contribution of the indigenous Thracian and Daco-Getic population, who had lived on the territory of modern Bulgaria and established here the Odrysian kingdom has been long debated among the scientists during the 20th century. However by the 5th century BC, the Thracian presence was pervasive enough to have made Herodotus (book 5) call them the second-most numerous people in the part of the world known by him (after the Indians). Some recent genetic studies reveal that these peoples have indeed made a significant contribution to the genes of the modern Bulgarian population.[49] The ancient languages of the local people had already gone extinct before the arrival of the Slavs, and their cultural influence was highly reduced due to the repeated barbaric invasions on the Balkans during the early Middle Ages by Goths, Celts, Huns, and Sarmatians, accompanied by persistent hellenization, romanisation and later slavicisation. The Celts also expanded down the Danube river and its tributaries in 3rd century BC. They had established a state on part of the territory of modern Bulgaria with capital Tylis, which they ruled for over a century.

The Slavs emerged from their original homeland (most commonly thought to have been in Eastern Europe) in the early 6th century, and spread to most of the eastern Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the Balkans, thus forming three main branches - the West Slavs, the East Slavs and the South Slavs. The easternmost South Slavs became part of the ancestors of the modern Bulgarians, which however, are genetically clearly separated from the tight DNA cluster of the most Slavic peoples. This phenomenon is explained by “the genetic contribution of the people who lived in the region before the Slavic expansion” [50]. The frequency of the proposed Slavic Haplogroup R1a1 ranges to 14.7% in Bulgaria.

Bulgars were a seminomadic people, probably of Turkic descent originally from Central Asia, who during the 2nd century migrated from the Northern portions of Central Asia into the North Caucasian steppe.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68] Between 377 and 453 they took part in the Hunnic raids on Central and Western Europe. Anthropological data collected from early Bulgar necropolises from Dobrudja, Crimea and the Ukrainian steppe shows that Bulgars were a high-statured Caucasoid people with a small Mongoloid admixture, and practiced artificial cranial deformation of the round type.[69][70][71][72][73][74] After Attila's death in 453, and the subsequent disintegration of the Hunnic Empire, the Bulgar tribes dispersed mostly to the eastern and southeastern parts of Europe. In the late 7th century, some Bulgar tribes, led by Asparukh and others, led by Kouber, permanently settled in the Balkans, and formed the ruling classe of First Bulgarian Empire in 680-681. It is possible that only a cultural and low genetic Bulgar influence was brought into the region, without modifying the genetic background of the local population.[75] The minor portions of Asian genes present within some modern Bulgarians, were likely introduced from the Bulgars and other steppe's peoples who also contributed to the Bulgarian ethnogenesis, as numbers of Kumans, Pechenegs and Avars, which is indicated through the limited presence of some rare alleles and haplotypes.[76][77]

Genetic origin

According to some 20th century researchers as William Z. Ripley, Carleton S. Coon and Bertil Lundman the Bulgarians are predominantly Mediterranean people, with unexplained Pre-Pontic, East-Baltic, and Nordic strains, whose roots goes back to the Neolithic.[78][79] However, data from Bulgarian mitochondrial DNA studies suggest that a human demographic expansion occurred sequentially in the Middle East, through Anatolia, to the rest of Europe (Bulgaria included). The rate estimates date of this expansion in times ranging around 50,000 years ago, corresponding to the arrival of anatomically modern humans in Europe.[80] Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup studies suggest an additional route of migration into Europe from Central Asia, via Russia, circa 40,000 years ago.[81] Also according to 21st century studies of their DNA data, the genetic background of the Bulgarians has classical eastern Mediterranean composition.[82] In physical appearance, the Bulgarian population is characterized by the features of the southern European anthropological type[83] with some additional influences. Genetically, modern Bulgarians are more closely related to other Balkan populations (Macedonians, Greeks, Romanians, Albanians, Croatians and Hungarians) than to the rest of the Europeans.[84][85][86] The Bulgarians also have minor similarities with other Mediterranean populations such as Armenians, Italians, Anatolians, Cretans and Sardinians.[87][88]

According to Eupedia, the Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup results about Bulgarians are the following: R1b - 18%, R1a - 14%, I - 37%, J2 - 17%, E1b1b - 12%.[89] In this way, a majority (>2/3) of the Bulgarians belong to one of the three major European Y-DNA haplogroups -- I, R1a and R1b. All three groups migrated to Europe during the Upper Paleolithic, around 30,000 BC. Around 10,000 ago, some neolithic lineages, originating in the Middle East, as J2 and E1b1b, have brought the agriculture to Europe, including today Bulgaria.

Population

Most Bulgarians live in the Republic of Bulgaria. There are significant Bulgarian minorities in Moldova and Ukraine (Bessarabian Bulgarians), as well as in Romania (Banat Bulgarians), Serbia (the Western Outlands), Greece, the Republic of Macedonia, Albania, and Hungary. Many Bulgarians also live in the diaspora, which is formed by representatives and descendants of the old (before 1989) and new (after 1989) emigration. The old emigration was made up of some 2,470,000 economic and several tens of thousands of political emigrants, and was directed for the most part to the U.S., Canada, Argentina, Brazil and Germany. The new emigration is estimated at some 970,000 people and can be divided into two major subcategories: permanent emigration at the beginning of the 1990s, directed mostly to the U.S., Canada, Austria, and Germany and labour emigration at the end of the 1990s, directed for the most part to Greece, Italy, the UK and Spain. Migrations to the West have been quite steady even in the late 1990s and early 21st century, as people continue moving to countries like the US, Canada and Australia. Most Bulgarians living in the US can be found in Chicago, Illinois. However, according to the 2000 US census most Bulgarians live in the cities of New York and Los Angeles, and the state with most Bulgarians in the US is California. Most Bulgarians living in Canada can be found in Toronto, Ontario, and the provinces with most Bulgarians in Canada are Ontario and Quebec. The largest urban populations of Bulgarians are to be found in Sofia (1,241,000), Plovdiv (378,000), and Varna (352,000)[90]. The total number of Bulgarians thus ranges anywhere from 17 to 18 million, depending solely on the estimation used for the diaspora.

Related ethnic groups

The ethnic Macedonians were considered Macedonian Bulgarians by the most ethnographers until the early 20th century and beyond with a big portion of them evidently self-identifying as such.[92][93] The Slavic-speakers of Greek Macedonia and most among the Torlaks in Serbia have also had a history of identifying as Bulgarians and many were members of the Bulgarian Exarchate. Greather part of these people were also considered Bulgarians by most of the ethnographers until the early 20th century and beyond.[94][95][96][97]

Culture

Cyrillic alphabet

Medieval Bulgaria was the most important cultural centre of the Slavic people at the end of the 9th and throughout the 10th century. The two literary schools of Preslav and Ohrid developed a rich literary and cultural activity with authors of the rank of Constantine of Preslav, John Exarch, Chernorizets Hrabar, Clement and Naum of Ohrid. In the first half of the 10th century, the Cyrillic alphabet was devised in the Preslav Literary School based on the Glagolitic and the Greek alphabets. Modern versions of the alphabet are now used to write five more Slavic languages such as Belarusian, Macedonian, Russian, Serbian and Ukrainian as well as Mongolian and some other 60 languages spoken in the former Soviet Union.

Bulgaria exerted similar influence on her neighbouring countries in the mid to late 14th century, at the time of the Turnovo Literary School, with the work of Patriarch Evtimiy, Gregory Tsamblak, Constantine of Kostenets (Konstantin Kostenechki). Bulgarian cultural influence was especially strong in Wallachia and Moldova where the Cyrillic alphabet was used until 1860, while Slavonic was the official language of the princely chancellery and of the church until the end of 17th century.

Art and science

Boris Christoff, Nicolai Ghiaurov, Raina Kabaivanska and Ghena Dimitrova made a precious contribution to opera singing with Ghiaurov and Christoff being two of the greatest bassos in the post-war period.The name of the harpist-Anna-Maria Ravnopolska-Dean is one of the best-known harpists today. Bulgarians have made valuable contributions to world culture in modern times as well. Julia Kristeva and Tzvetan Todorov were among the most influential European philosophers in the second half of the 20th century. The artist Christo is among the most famous representatives of environmental art with projects such as the Wrapped Reichstag.

Bulgarians in the diaspora have also been active. American scientists and inventors of Bulgarian descent include John Atanasoff, Peter Petroff, and Assen Jordanoff. Bulgarian-American Stephane Groueff wrote the celebrated book "Manhattan Project", about the making of the first atomic bomb and also penned "Crown of Thorns", a biography of Tsar Boris III of Bulgaria.

Sport

In the beginning of the 20th century Bulgaria was famous for two of the best wrestlers in the world - Dan Kolov and Nikola Petroff. High-jumper Stefka Kostadinova was one of the top ten female athletes of the last century and holds one of the oldest unbroken world records in athletics. Hristo Stoichkov was one of the best football (soccer) players in the second half of the 20th century, having played with the national team and FC Barcelona. He received a number of awards and was the joint top scorer at the 1994 World Cup.

Language

Bulgarians speak a Southern Slavic language which is similar to Serbo-Croatian and is limitedly mutually intelligible with it. The Bulgarian language is also, to some degree, mutually intelligible with Russian on account of the influence which Russia has had on the development of Modern Bulgaria since 1878, as well as the earlier effect of Old Bulgarian on the development of Old Russian. Although related, Bulgarian and the Western and Eastern Slavic languages are not mutually intelligible.

Bulgarian demonstrates several linguistic developments that set it apart from other Slavic languages. These are shared with Romanian, Albanian and Greek (see Balkan linguistic union). Until 1878 Bulgarian was influenced lexically by medieval and modern Greek, and to a much lesser extent, by Turkish. More recently, the language has borrowed many words from Russian, German, French and English.

Some members of the diaspora do not speak the Bulgarian language (mostly representatives of the old emigration in the U.S., Canada and Argentina) but are still considered Bulgarians by ethnic origin or descent.

The majority of the Bulgarian linguists, consider the officialized Macedonian language, since 1944, a local variation of Bulgarian, although the linguistic consensus suggests that a language is a language if its speakers define it as such. The Bulgarian language is written in the Cyrillic alphabet.

Name system

There are several different layers of Bulgarian names. The vast majority of them have either Christian (names like Lazar, Ivan, Anna, Maria, Ekaterina) or Slavic origin (Vladimir, Svetoslav, Velislava). After the Liberation in 1878, the names of historical Bulgar rulers like Asparuh, Krum, Kubrat and Tervel were resurrected. The old Bulgar name Boris has spread from Bulgaria to a number of countries in the world with Russian tsar Boris Godunov and German tennis player Boris Becker being two of the examples of its use.

Most Bulgarian male surnames have an -ov surname suffix (Cyrillic: -ов). This is sometimes transcribed as -off (John Atanasov — John Atanasoff, but more often as -ov e.g. Boris Hristov). The -ov suffix is the Slavic gender-agreeing suffix, thus Ivanov (Template:Lang-bg) literally means "Ivan's". Bulgarian middle names are patronymic and use the gender-agreeing suffix as well, thus the middle name of Nikola's son becomes Nikolov, and the middle name of Ivan's son becomes Ivanov. Since names in Bulgarian are gender-based, Bulgarian women have the -ova surname suffix (Cyrillic: -овa), for example, Maria Ivanova. The plural form of Bulgarian names ends in -ovi (Cyrillic: -ови), for example the Ivanovi family (Иванови).

Other common Bulgarian male surnames have the -ev surname suffix (Cyrillic: -ев), for example Stoev, Ganchev, Peev, and so on. The female surname in this case would have the -eva surname suffix (Cyrillic: -ева), for example: Galina Stoeva. The last name of the entire family then would have the plural form of -evi (Cyrillic: -еви), for example: the Stoevi family (Стоеви).

Another typical Bulgarian surname suffix, though much less common, is -ski. This surname ending also gets an –a when the bearer of the name is female (Smirnenski becomes Smirnenska). The plural form of the surname suffix -ski is still -ski, e.g. the Smirnenski family (Template:Lang-bg).

The surname suffix -ich can be found sometimes, primarily among Catholic Bulgarians. The ending –in (female -ina) also appears sometimes, though rather seldom. It used to be given to the child of an unmarried woman (for example the son of Kuna will get the surname Kunin and the son of Gana – Ganin). The surname ending –ich does not get an additional –a if the bearer of the name is female.

Religion

Most Bulgarians are at least nominally members of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church founded in 870 AD (autocephalous since 927 AD). The Bulgarian Orthodox Church is the independent national church of Bulgaria like the other national branches of Eastern Orthodoxy and is considered an inseparable element of Bulgarian national consciousness. The church has been abolished twice during the periods of Byzantine (1018—1185) and Ottoman (1396—1878) domination but was revived every time as a symbol of Bulgarian statehood. In 2001, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church had a total of 6,552,000 members in Bulgaria (82.6% of the population) and between one and two million members in the diaspora. The Orthodox Bulgarian minorities in Serbia, Romania, Moldova and Ukraine still hold allegiance to the respective national Orthodox churches.

Despite the position of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church as a unifying symbol for all Bulgarians, smaller or larger groups of Bulgarians have converted to other faiths or denominations through the course of time. In the 16th and the 17th century Roman Catholic missionaries converted the Bulgarian Paulicians in the districts of Plovdiv and Svishtov to Roman Catholicism. Nowadays there are some 40,000 Catholic Bulgarians in Bulgaria and additional 10,000 in the Banat in Romania. The Catholic Bulgarians of the Banat are also descendants of Paulicians who fled there at the end of the 17th century after an unsuccessful uprising against the Ottomans.

Protestantism was introduced in Bulgaria by missionaries from the United States in 1857. Missionary work continued throughout the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century. In 2001, there were some 25,000 Protestant Bulgarians in Bulgaria.

Between the 15th and the 20th century, during the Ottoman rule, a large number of Orthodox Bulgarians converted to Islam. Their descendants now form the second largest religious congregation in Bulgaria. In 2001, there were 131,000 Muslim Bulgarians or Pomaks in Bulgaria in the Rhodope region, as well as some villages in the Teteven region in Central North Bulgaria. Their origins are obscure,[98] but they are generally believed to be Bulgarians who converted to Islam during the period of Ottoman rule in the Balkans.[99]

.

Symbols

The national symbols of the Bulgarians are the Flag of Bulgaria and the Coat of Arms of Bulgaria.

The national flag of Bulgaria is a rectangle with three colors: white, green, and red, positioned horizontally top to bottom. The color fields are of same form and equal size.

The Coat of Arms of Bulgaria is a state symbol of the sovereignty and independence of the Bulgarian people and state. It represents a crowned rampant golden lion on a dark red background with the shape of a shield. Above the shield there is a crown modeled after the crowns of the emperors of the Second Bulgarian Empire, with five crosses and an additional cross on top. Two crowned rampant golden lions hold the shield from both sides, facing it. They stand upon two crossed oak branches with acorns, which symbolize the power and the longevity of the Bulgarian state. Under the shield, there is a white band lined with the three national colors. The band is placed across the ends of the branches and the phrase "Unity Makes Strength" is inscribed on it.

Both the Bulgarian flag and the Coat of Arms are also used as symbols of various Bulgarian organisations, political parties and institutions.

Bulgarians. Faces through history

-

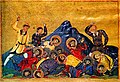

Miniature from the Constantine Manasses Chronicle, Emperor Michael II defeats the army of Thomas the Slav.

-

Khan Omurtag (815-831), warrior and builder

-

Saint Knyaz Boris I (852–889), converted the Bulgarians to Christianity

-

Tsar Samuil, the last ruler of the First Bulgarian Empire (997–1014)

-

Tsar Kaloyan of Bulgaria (1197-1207)

-

A fresco from Boyana Church near Sofia depicting Desislava, a church patron (1259)

-

Gregory Tsamblak (left), a Bulgarian writer and cleric, as Metropolitan of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania on the Council of Constance (15th century)

-

Bulgarian women from the period of the Ottoman Empire rule (16th century)

-

Rostislav Stratimirovic, Prince of Tarnovo (17th century)

-

Paisiy Hilendarski, a key figure in Bulgarian National Revival from Macedonia (18th century)

-

Bulgarian peasants with Bulgarian merchant and his son in the late Ottoman Empire, 1860s'

-

Knyaz Alexander Batenberg, first ruler of modern Bulgaria

-

Nathanael Ohridski, organizer of the Kresna-Razlog Uprising

-

Vasil Levski, national hero of Bulgaria

-

Ivan Mihailov, Bulgarian revolutionary, leader of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary OrganizationIvan Mihailov, Bulgarian revolutionary, leader of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

-

Vladimir Vazov, Bulgarian general and war hero

-

Todor Zhivkov, a leader of the People's Republic of Bulgaria

-

Vesselin Topalov, former world chess champion

-

Nayden Todorov, is a Bulgarian conductor

-

Simeon II, the last Tsar of Bulgaria

References and notes

- ^ "Pomak speakers (Bulgarian Muslims) in Turkey". Ethnolugue:Languages of the World. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- ^ "General results of the 2001 Ukrainian census by nationality". www.ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ "Министерство на външните работи - Българска общност". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- ^ http://www.destatis.de/jetspeed/portal/cms/Sites/destatis/SharedContent/Oeffentlich/AI/IC/Publikationen/Jahrbuch/Bevoelkerung,property=file.pdf

- ^ US census

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in the US according to the consulate in Washington D.C." www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ^ 2006 figures

- ^ 2001 Greek Census, Population by Nationality: Απογραφή πληθυσμού της 18ης Μαρτίου 2001

- ^

"Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in the UK [[:Template:Bg icon]]". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^

"Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Argentina [[:Template:Bg icon]]". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "Foreign citizens in Italy". demo.istat.it. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Italy". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ "Russian census 2002". Russia. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ "Results of the 2001 Canadian census". www12.statcan.ca. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ "Министерство на външните работи - Българска общност". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Serbia and Montenegro 2002 census

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in France". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ Countries of the Eu by Birth

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in South Africa". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ Recensamant 2002

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Israel". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.The first number indicates people that have Bulgarian citizenship and the second represent those coming from Bulgaria in the 1940s and 1950s who are members of Associations of Bulgarian jews

- ^ Population of Kazakhstan as of 1989 and 1999

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Kazakhstan". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30. According to members of the Bulgarian community in Kazakhstan their number is between 30,000 and 50,000

- ^ New Title

- ^ "2001 Hungarian Census, Ethnic group tables". www.nepszamlalas.hu. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Hungary". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ "All Bulgarians". Protestan Group. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in UAE". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ "2006 Census Table : Australia". www.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Sweden". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ Country of Birth

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Portugal". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ Eurostat

- ^

"Statistics Netherlands, Population Tables". http://statline.cbs.nl. Retrieved 2008-04-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Netherlands". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Ireland". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^

"Statistical Service of New Zealand, New Zealanders by Ancestry". www.stats.gov.nz. Retrieved 2008-04-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in New Zealand". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Norway". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ "Population by Country of Birth". OECD. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ^ Results of the 2002 census

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Syria". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Poland". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Jordan". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^

"Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Georgia according to the 1989 census [[:Template:Bg icon]]". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^

"Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria - Bulgarians in Denmark [[:Template:Bg icon]]". www.mfa.bg. Retrieved 2008-04-28.{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "2002 Slovenian census". www.stat.si. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ Bulgaria, Authors Richard Watkins, Christopher Deliso, Edition 3, illustrated, Publisher Lonely Planet, 2008, ISBN 174104474X, 9781741044744, p. 309.

- ^ Paleo-MtDNA Analysis and population genetic aspects of old Thracian population from South-Eastern Romania

- ^ Anthropological Evidence and the Fallmerayer Thesis

- ^ Columbia Encyclopedia: Eastern Bulgars

- ^ Образуване на българската държава. проф. Петър Петров (Издателство Наука и изкуство, София, 1981)

- ^ Образуване на българската народност.проф. Димитър Ангелов (Издателство Наука и изкуство, “Векове”, София, 1971)

- ^ A history of the First Bulgarian Empire.Prof. Steven Runciman (G. Bell & Sons, London 1930)

- ^ История на българската държава през средните векове Васил Н. Златарски (I изд. София 1918; II изд., Наука и изкуство, София 1970, под ред. на проф. Петър Хр. Петров)

- ^ История на българите с поправки и добавки от самия автор акад. Константин Иречек (Издателство Наука и изкуство, 1978) проф. Петър Хр. Петров

- ^ Heinz Siegert: Osteuropa – Vom Ursprung bis Moskaus Aufstieg, Panorama der Weltgeschichte, Bd. II, hg. von Dr. Heinrich Pleticha, Gütersloh 1985, p. 46

- ^ P. B. Golden An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. - Wisbaden, 1992. - p.92-104

- ^ [René Grousset: Die Steppenvölker, München 1970, p. 249]

- ^ Harald Haarmann: Protobulgaren in: Lexikon der untergegangenen Völker, München 2005, p.225

- ^ Rashev, Rasho. 1992. On the origin of the Proto-Bulgarians. p. 23-33 in: Studia protobulgarica et mediaevalia europensia. In honour of Prof. V. Beshevliev, Veliko Tarnovo

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica Online - Bolgar Turkic

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica Online - Bulgars

- ^ Sedlar, Jean W. East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. University of Washington Press, 1994. page 6

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica Online - Bulgar

- ^ Bowersock, G. W. & Grabar, Oleg. Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press, 1998. page 354

- ^ Chadwick, Henry. East and West: The Making of a Rift in the Church : from Apostolic Times. Oxford University Press, 2003. page 109

- ^ Reuter, Timothy. The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge University Press, 2000. page 492

- ^ D.Dimitrov,1987, History of the Proto-Bulgarians north and west of the Black Sea.

- ^ Сарматски елементи в езическите некрополи от Североизточна България и Северна Добруджа. Елена Ангелова (сп. Археология, 1995, 2, 5-17, София)

- ^ М. Б а л а н, П. Б о е в. Антропологични материали от некропола при Нови пазар. — ИАИ, XX, 1955, 347— 371

- ^ Й. Ал. Й о р д а н о в. Антропологично изследване на костния материал от раннобългарски масов гроб при гр. Девня. - ИНМВ, XII (XVII), 1976, 171-194

- ^ Н. К о н д о в а, П. Б о е в, С л. Ч о л а к о в. Изкуствено деформирани черепи от некропола при с. Кюлевча, Шуменски окръг. — Интердисциплинарни изследвания, 1979, 3—4, 129— 138;

- ^ Н. К о н д о в а, С л. Ч о лаков. Антропологични данни за етногенеза на ранносредновековната популация от Североизточна България. — Българска етнография, 1992, 2, 61-68

- ^ HLA genes in the Chuvashian population from European Russia: Admixture of central European and Mediterranean populations - pg. 5

- ^ Five polymorphisms of the apolipoprotein B gene in healthy Bulgarians. Human Biology, Feb 2003.[1]

- ^ On the origin of Mongoloid component in the mitochondrial gene pool of Slavs. Russian Journal of Genetics. Volume 44, Number 3 / March, 2008

- ^ Races Of Europe, (Chapter XII, section 15)

- ^ Lundman, Bertil J. - The Races and Peoples of Europe, (Chapter: The Races and Peoples of Southeast Europe), New York: IAAEE. 1977.

- ^ From Asia to Europe: mitochondrial DNA sequence variability in Bulgarians and Turks. Ann Hum Gen.1996.Jan;60 (Pt 1):35-49. [2]

- ^ Semino et al. (2000),The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans, Science Vol 290. Note: Haplogroup names are different in this article. For ex: Haplogroup I is referred as M170

- ^ HLA genes in the Chuvashian population from European Russia: Admixture of central European and Mediterranean populations - pg. 5

- ^ HLA-DRB1, DQA1, DQB1 DNA polymorphism in the Bulgarian population.Division of Clinical and Transplantation Immunology, Medical University, Sofia, Bulgaria.

- ^ Five polymorphisms of the apolipoprotein B gene in healthy Bulgarians.Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Medical University of Sofia, Bulgaria.PMID: 12713147

- ^ HLA polymorphism in Bulgarians defined by high-resolution typing methods in comparison with other populations.

- ^ Y-chromosomal diversity in Europe is clinal and influenced primarily by geography, rather than by language

- ^ Distributions of HLA class I alleles and haplotypes in Bulgarians – contribution to understanding the origin of the population. M. Ivanova, P. Spassova, A. Michailova, E. Naumova. Division of Clinical and Transplantation Immunology, Medical University, Sofia, Bulgaria.

- ^ Bulgarian Bone Marrow Donors Registry—past and future directions - Asen Zlatev, Milena Ivanova, Snejina Michailova, Anastasia Mihaylova and Elissaveta Naumova, Central Laboratory of Clinical Immunology, University Hospital “Alexandrovska”, Sofia, Bulgaria, Published online: 2 June 2007

- ^ Distribution of European Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups by region in percentage.

- ^ Главна Дирекция Гражданска Регистрация и Административно Обслужване

- ^ Illustration from Fox, Frank, Sir Bulgaria (1915) London: A. and C. Black, Ltd., p. 25. e-book #22257 in Project Gutenberg

- ^ Cousinéry, Esprit Marie. Voyage dans la Macédoine: contenant des recherches sur l'histoire, la géographie, les antiquités de ce pay, Paris, 1831, Vol. II, p. 15-17, one of the passages in English - [3], Engin Deniz Tanir, The Mid-Nineteenth century Ottoman Bulgaria from the viewpoints of the French Travelers, A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University, 2005, p. 99, 142

- ^ Pulcherius, Receuil des historiens des Croisades. Historiens orientaux. III, p. 331 – a passage in English -http://promacedonia.org/en/ban/nr1.html#4

- ^ The struggle for Greece, 1941-1949, Christopher Montague Woodhouse, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2002, ISBN 1850654921, p. 67.

- ^ Who are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1995, ISBN 1850652384,p. 109.

- ^ Felix Philipp Kanitz, (Das Konigreich Serbien und das Serbenvolk von der Romerzeit bis dur Gegenwart, 1904, in two volume) # "In this time (1872) they (the inhabitants of Pirot) did not presume that six years later the often damn Turkish rule in their town will be finished, and at least they did not presume that they will be include in Serbia, because they always feel that they are Bulgarians. ("Србија, земља и становништво од римског доба до краја XIX века", Друга књига, Београд 1986, p. 215)

- And today (in the end of XIX century) among the older generation there are many fondness to Bulgarians, that it led him to collision with Serbian government. Some hesitation can be noticed among the youngs..." ("Србија, земља и становништво од римског доба до краја XIX века", Друга књига, Београд 1986, c. 218; Serbia - its land and inhabitants, Belgrade 1986, p. 218)

- ^ Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui, „Voyage en Bulgarie pendant l'année 1841“ (Жером-Адолф Бланки. Пътуване из България през 1841 година. Прев. от френски Ел. Райчева, предг. Ив. Илчев. София: Колибри, 2005, 219 с. ISBN 978-954-529-367-2.) It describes a population in Nish sandjak as Bulgarian, see: [4]

- ^ F. De Jong, "The Muslim Minority in Western Thrace", (1980), p. 95

- ^ A Country Study: Bulgaria, "Pomaks", (1992)

- ^ "Even the famous leader of the Macedonian revolutionaries, Gotse Delchev, openly said that “We are Bulgarians” and addressed “the Slavs of Macedonia as ‘Bulgarians’ in an offhanded manner without seeming to indicate that such a designation was a point of contention”; See:The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, Loring M. Danforth, Editor: Princeton University Press, 1997, ISBN 0691043566,p. 64.

- ^ "...Goce Delchev and the other leaders of the BMORK were aware of Serbian and Greek ambitions in Macedonia. More important, they were aware that neither Belgrade nor Athens could expect to obtain the whole of Macedonia and, unlike Bulgaria, looked forward to and urged partition of this land. Autonomy, then, was the best prophylactic against partition – a prophylactic that would preserve the Bulgarian character of Macedonia's Christian population despite the separation from Bulgaria proper..." See: The Macedoine, (pp. 307-328 in of "The National Question in Yugoslavia. Origins, History, Politics" by Ivo Banac, Cornell University Press, 1984)

See also

- List of Bulgarians

- Bulgarian diaspora

- Bulgarian Americans

- Bulgarian Canadians

- Bulgarians in South America

- Bulgarian Australian

- Bulgarians in Serbia

- Banat Bulgarians

- Bessarabian Bulgarians

- Bulgaria

- Bulgars

- History of Bulgaria

- Bulgarian language

- Music of Bulgaria

- Bulgarian cuisine

- Macedonians (ethnic group)

- Old Great Bulgaria

- Bulgarian months

![Gotse Delchev, leader of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees.[100][101]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/G_Delchev.jpg/82px-G_Delchev.jpg)