James Watt

James Watt | |

|---|---|

Portrait of James Watt (1736-1819) by Carl Frederik von Breda | |

| Born | 19 January 1736 |

| Died | 25 August 1819 (aged 83)[1] |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Improving the steam engine |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Inventor and Mechanical Engineer |

| Institutions | University of Glasgow Boulton and Watt |

Cockface mofo!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

James Watt FRS (19 January 1736 – 25 August 1819)[1] was a Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer whose improvements to the steam engine were fundamental to the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution in both the Kingdom of Great Britain and the world.

Biography

James Watt was born on 19 January 1736 in Greenock, Renfrewshire, a seaport on the Firth of Clyde. His father was a shipwright, ship owner and contractor, and served as the town's chief baillie, while his mother, Agnes Muirhead, came from a distinguished family and was well educated. Both were Presbyterians and strong Covenanters. Watt's grandfather, Thomas Watt, was a mathematics teacher and baillie to the Baron of Cartsburn. Watt did not attend school regularly; initially he was mostly schooled at home by his mother but later he attended Greenock grammar school.[2] He exhibited great manual dexterity and an aptitude for mathematics, although Latin and Greek failed to interest him, and he absorbed the legends and lore of the Scottish people.

When he was 18, his mother died and his father's health had begun to fail. Watt travelled to London to study instrument-making for a year, then returned to Scotland – to Glasgow – intent on setting up his own instrument-making business. However, because he had not served at least seven years as an apprentice, the Glasgow Guild of Hammermen (any artisans using hammers) blocked his application, despite there being no other mathematical instrument makers in Scotland.

Watt was saved from this impasse by three professors of the University of Glasgow, who offered him the opportunity to set up a small workshop within the university. It was established in 1758 and one of the professors, the physicist and chemist Joseph Black, became Watt's friend.

In 1764, Watt married his cousin Margaret Miller, with whom he had five children, two of whom lived to adulthood. She died in childbirth in 1772. In 1777 he married again, to Ann MacGregor, daughter of a Glasgow dye-maker, who survived him. She died in 1832.

Watt had a brother by the name of John. He was shipwrecked when James was 17.

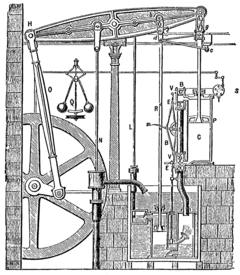

Four years after Watt had opened his workshop, his friend, Professor John Robison, called his attention to the use of steam as a source of power, and Watt began to experiment with it. Watt had never seen an operating steam engine, but he tried constructing a model. It failed to work satisfactorily, but he continued his experiments and began to read everything he could about the subject. He independently discovered the importance of latent heat in understanding the engine, which, unknown to him, Black had famously discovered some years before. He learned that the University owned a model Newcomen engine, but it was in London for repairs. Watt got the university to have it returned, and he made the repairs in 1763.

It too just barely worked, and after much experimentation he showed that about 80% of the heat of the steam was consumed in heating the cylinder, because the steam in it was condensed by an injected stream of cold water. His critical insight was to cause the steam to condense in a separate chamber apart from the piston, and to maintain the temperature of the cylinder at the same temperature as the injected steam. He soon had a working model by 1765.

Now came a long struggle to produce a full-scale engine. This required more capital, some of which came from Black. More substantial backing came from John Roebuck, the founder of the celebrated Carron Iron Works, near Falkirk, with whom he now formed a partnership. But the principal difficulty was in machining the piston and cylinder. Iron workers of the day were more like blacksmiths than machinists, so the results left much to be desired. Much capital was spent in pursuing the ground-breaking patent. An extension of the patent was successfully obtained (James Watt's Fire Engines Patent Act, 1775 (15 Geo 3 c. 61), which in those days required an Act of Parliament. Strapped for resources, Watt was forced to take up employment as a surveyor for eight years. Roebuck went bankrupt, and Matthew Boulton, who owned the Soho Foundry works near Birmingham, acquired his patent rights. Watt and Boulton formed a hugely successful partnership (Boulton & Watt), which lasted for the next twenty-five years.

Watt finally had access to some of the best iron workers in the world. The difficulty of the manufacture of a large cylinder with a tightly fitting piston was solved by John Wilkinson who had developed precision boring techniques for cannon making at Bersham, near Wrexham, North Wales.

Finally, in 1776, the first engines were installed and working in commercial enterprises. These first engines were used for pumps and produced only reciprocating motion to move the pump rods at the bottom of the shaft. Orders began to pour in and for the next five years Watt was very busy installing more engines, mostly in Cornwall for pumping water out of mines.

The field of application of the invention was greatly widened only after Boulton urged Watt to convert the reciprocating motion of the piston to produce rotational power for grinding, weaving and milling. Although a crank seemed the logical and obvious solution to the conversion Watt and Boulton were stymied by a patent for this, whose holder, James Pickard, and associates proposed to cross-license the external condenser. Watt adamantly opposed this and they circumvented the patent by their sun and planet gear in 1781.

Over the next six years, he made a number of other improvements and modifications to the steam engine. A double acting engine, in which the steam acted alternately on the two sides of the piston was one. He described methods for working the steam expansively. A compound engine, which connected two or more engines was described. Two more patents were granted for these in 1781 and 1782. Numerous other improvements that made for easier manufacture and installation were continually implemented. One of these included the use of the steam indicator which produced an informative plot of the pressure in the cylinder against its volume, which he kept as a trade secret. Another important invention, one of which Watt was most proud of, was the Parallel motion / three-bar linkage which was especially important in double-acting engines as it produced the straight line motion required for the cylinder rod and pump, from the connected rocking beam, whose end moves in a circular arc. This was patented in 1784. A throttle valve to control the power of the engine, and a centrifugal governor, patented in 1788,[3] to keep it from "running away" were very important. These improvements taken together produced an engine which was up to five times as efficient in its use of fuel as the Newcomen engine.

Because of the danger of exploding boilers and the ongoing issues with leaks, Watt was opposed from the first to the use of high pressure steam--all of his engines used steam at very low pressure.

In 1794 the partners established Boulton and Watt to exclusively manufacture steam engines, and this became a large enterprise. By 1824 it had produced 1164 steam engines having a total nominal horsepower of about 26,000.[4] Boulton proved to be an excellent businessman, and both men eventually made fortunes.

Method and personality

Watt was an enthusiastic inventor, with a fertile imagination that sometimes got in the way of finishing his works, because he could always see "just one more improvement". He was skilled with

HELLO! HOW R UU?

The garret room workshop that Watt used in his retirement was left locked and untouched until 1853, when it was first viewed by his biographer J. P. Muirhead. Thereafter, it was occasionally visited, but left untouched, as a kind of shrine. A proposal to have it transferred to the Patent Office came to nothing. When the house was due to be demolished in 1924, the room and all its contents were presented to the Science Museum, where it was recreated in its entirety.[5] It remained on display for visitors for many years, but was walled-off when the gallery it was housed in closed. The workshop remains intact, and preserved, and there are plans for it to go on display again at some point in the near future.

Controversy

As with many major inventions, there is some dispute as to whether Watt was the original sole inventor of some of the numerous inventions he patented. There is no dispute, however, that he was the sole inventor of his most important invention, the separate condenser. It was his practice (from around the 1780s) to pre-empt others' ideas which were known to him by filing patents with the intention of securing credit for the invention for himself, and ensuring that no one else was able to practice it. As he states in a letter to Boulton of 17 August 1784:

- I have given such descriptions of engines for wheel carriages as I could do in the time and space I could allow myself; but it is very defective and can only serve to keep other people from similar patents.

Some argue that his prohibitions on his employee William Murdoch from working with high pressure steam on his steam road locomotive experiments delayed its development. Watt, with his partner Matthew Boulton, battled against rival engineers such as Jonathan Hornblower who tried to develop engines which did not fall foul of his patents.

Watt patented the application of the sun and planet gear to steam in 1781 and a steam locomotive in 1784, both of which have strong claims to have been invented by his employee, William Murdoch. Watt himself described the provenance of the invention of the sun and planet gear in a letter to Boulton from Watt dated 5 January 1782:

- I have tried a model of one of my old plans of rotative engines revived and executed by W. M[urdock] and which merits being included in the specification as a fifth method...

The patent was never contested by Murdoch, who remained an employee of Boulton and Watt for most of his life, and Boulton and Watt's firm continued to use the sun and planet gear in their rotative engines, even long after the patent for the crank expired in 1794.

Legacy

James Watt's improvements transformed the Newcomen engine, which had hardly changed for fifty years, and initiated changes in generating and applying power, which transformed the world of work, and were a key innovation of the Industrial Revolution. The importance of the invention can hardly be overstated--it gave us the modern world. A key feature of it was that it brought the engine out of the remote coal fields into factories where many mechanics, engineers, and even tinkerers were exposed to its virtues and limitations. It was a platform for generations of inventors to improve. It was clear to many that higher pressures produced in improved boilers would produce engines having even higher efficiency, and would lead to the revolution in transportation that was soon embodied in the locomotive and steamboat. It made possible the construction of new factories that, since they were not dependent on water power, could work the year round, and could be placed almost anywhere. Work was moved out of the cottages, resulting in economies of scale. Capital could work more efficiently, and manufacturing productivity greatly improved. It made possible the cascade of new sorts of machine tools that could be used to produce better machines, including that most remarkable of all of them, the Watt steam engine.

Of Watt, the English Novelist Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) wrote; "To us, the moment 8:17 A.M. means something - something very important, if it happens to be the starting time of our daily train. To our ancestors, such an odd eccentric instant was without significance - did not even exist. In inventing the locomotive, Watt and Stephenson were part inventors of time."

Suck this!

Honours

Watt was a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Royal Society of London. He was a member of the Batavian Society, and one of only eight Foreign Associates of the French Academy of Sciences.

The watt is named after James Watt for his contributions to the development of the steam engine, and was adopted by the Second Congress of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1889 and by the 11th General Conference on Weights and Measures in 1960 as the unit of power incorporated in the International System of Units (or "SI"). The watt is named after James Watt. As with every SI unit named for a person, its symbol starts with an upper case letter (W), but when written in full, it follows the rules for capitalisation of a common noun; i.e., watt becomes capitalised at the beginning of a sentence and in titles but is otherwise in lower case.

Memorials

Watt was buried in the grounds of St. Mary's Church, Handsworth, in Birmingham. Later expansion of the church, over his grave, means that his tomb is now buried inside the church. A statue of him, Boulton and Murdoch is in Birmingham, as are five other statues of him alone, one in Chamberlain Square, the other outside the Law Courts. He is also remembered by the Moonstones and a school is named in his honour, both in Birmingham. An extensive archive of his papers is held at Birmingham Central Library. Matthew Boulton's home, Soho House, is now a museum, commemorating the work of both men. The University of Glasgow's Faculty of Engineering, the oldest in the United Kingdom, (where Watt was a professor) has its headquarters in the James Watt Building, which also houses the department of Mechanical Engineering and the department of Aerospace Engineering.

The location of James Watt's birth in Greenock is commemorated by a statue, close to his birthplace. Several locations and street names in Greenock recall him, most notably the Watt Memorial Library, which was begun in 1816 with Watt's donation of scientific books, and developed as part of the Watt Institution by his son (which ultimately became the James Watt College). Taken over by the local authority in 1974, the library now also houses the local history collection and archives of Inverclyde, and is dominated by a large seated statue in the vestibule. Watt is additionally commemorated by statuary in George Square, Glasgow and Princes Street, Edinburgh.

The James Watt College has expanded from its original location to include campuses in Kilwinning (North Ayrshire), Finnart Street and The Waterfront in Greenock, and the Sports campus in Largs. Heriot-Watt University near Edinburgh was at one time the School of Arts of Edinburgh, founded in 1821 as the world’s first Mechanics Institute, but to commemorate George Heriot, the 16th century financier to King James, and James Watt, after Royal Charter the name was changed to Heriot-Watt University. Dozens of university and college buildings (chiefly of science and technology) are named after him.

The huge painting James Watt contemplating the steam engine by James Eckford Lauder is now owned by the National Gallery of Scotland.

Watt was ranked first, tying with Edison, among 229 significant figures in the history of technology by Charles Murray's survey of historiometry presented in his book Human Accomplishments. Watt was ranked 22nd in Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.

Over 50 roads or streets in the UK are named after him.

A colossal statue of Watt by Chantrey was placed in Westminster Abbey, and later was moved to St. Paul's Cathedral. On the cenotaph the inscription reads:

- NOT TO PERPETUATE A NAME,

- WHICH MUST ENDURE WHILE THE PEACEFUL ARTS FLOURISH,

- BUT TO SHOW

- THAT MANKIND HAVE LEARNED TO HONOUR THOSE

- WHO BEST DESERVE THEIR GRATITUDE,

- THE KING,

- HIS MINISTERS, AND MANY OF THE NOBLES

- AND COMMONERS OF THE REALM

- RAISED THIS MONUMENT TO

- JAMES WATT

- WHO DIRECTING THE FORCE OF AN ORIGINAL GENIUS

- EARLY EXERCISED IN PHILOSOPHIC RESEARCH

- TO THE IMPROVEMENT OF

- THE STEAM-ENGINE

- ENLARGED THE RESOURCES OF HIS COUNTRY

- INCREASED THE POWER OF MAN

- AND ROSE TO AN EMINENT PLACE

- AMONG THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS FOLLOWERS OF SCIENCE

- AND THE REAL BENEFACTORS OF THE WORLD

- BORN AT GREENOCK MDCCXXXVI

- DIED AT HEATHFIELD IN STAFFORDSHIRE MDCCCXIX

A lecture theatre in the Mechanical & Manufacturing Engineering building at the University of Birmingham is named 'G31 - The James Watt Lecture Theatre'.

On 29 May 2009, the Bank of England announced that Watt would appear on a new £50 note, alongside Matthew Boulton.[6]

See also

- Watt steam engine

- Centrifugal governor

- Indicator diagram

- Watt's linkage

- Parallel motion

- Sun and planet gear

References

- ^ a b Although a number of otherwise reputable sources give his date of death as 19 August 1819, all contemporary accounts report him dying on 25 August and being buried on 2 September. The date 19 August originates from the biography The Life of James Watt (1858, p. 521) by James Patrick Muirhead. It draws its (supposed) legitimation from the fact that Muirhead was a nephew of Watt and therefore should have been a particularly well-informed informant. In the Muirhead papers, however, the 25 August date is mentioned elsewhere. The latter date is also given in contemporary newspaper reports (for example, page 3 of The Times of 28 August) as well as by an abstract of and codicil to Watt’s last will. (In the pertinent burial register of St. Mary’s Church (Birmingham-Handsworth) Watt’s date of death is not mentioned.)

- ^ Tann, Jennifer (2004). "James Watt (1736–1819)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Brown, Richard (1991). Society and Economy in Modern Britain 1700-1850. London: Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 9780203402528.

- ^ Carnegie, p 195

- ^ Garret workshop of James Watt

- ^ "Steam giants on new £50 banknote". BBC. 2009-5-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Further reading

- "Some Unpublished Letters of James Watt" in Journal of Institution of Mechanical Engineers (London, 1915).

- Carnegie, Andrew, James Watt University Press of the Pacific (2001) (Reprinted from the 1913 ed.), ISBN 0-89875-578-6.

- Dickenson, H. W. (1935). James Watt: Craftsman and Engineer. Cambridge University Press.

- H. W. Dickinson and Hugh Pembroke Vowles James Watt and the Industrial Revolution (published in 1943, new edition 1948 and reprinted in 1949. Also published in Spanish and Portuguese (1944) by the British Council)

- Hills, Rev. Dr. Richard L., James Watt, Vol 1, His time in Scotland, 1736-1774 (2002); Vol 2, The years of toil, 1775-1785; Vol 3 Triumph through adversity 1785-1819. Landmark Publishing Ltd, ISBN 1-84306-045-0.

- Hulse David K. (1999). The early development of the steam engine. Leamington Spa, UK: TEE Publishing. pp. 127–152. ISBN 1 85761 107 1.

- Hulse David K. (2001). The development of rotary motion by steam power. Leamington, UK: TEE Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1 85761 119 5.

- Marsden, Ben. Watt's Perfect Engine Columbia University Press (New York, 2002) ISBN 0-231-13172-0.

- Muirhead, James Patrick (1854). Origin and Progress of the Mechanical Inventions of James Watt. London: John Murray.

- Muirhead, James Patrick (1858). The Life of James Watt. London: John Murray.

- Samuel Smiles, Lives of the Engineers, (London, 1861-62, new edition, five volumes, 1905).

- Related topics

- Schofield, Robert E. (1963). The Lunar Society, A Social History of Provincial Science and Industry in Eighteenth Century England. Clarendon Press.

- Uglow, Jenny (2002). The Lunar Men. London: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

External links

- James Watt by Andrew Carnegie (1905)

- James Watt by Thomas H. Marshall (1925)

- Archives of Soho at Birmingham Central Library.

- BBC History: James Watt

- Revolutionary Players website

- Cornwall Record Office Boulton & Watt letters

- Significant Scots - James Watt

- "Chapter 8: The Record of the Steam Engine". www.history.rochester.edu. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- Mechanical engineers

- People of the Industrial Revolution

- Scottish business theorists

- Scottish businesspeople

- Scottish engineers

- Scottish inventors

- Scottish surveyors

- Alumni of the University of Glasgow

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- People associated with Heriot-Watt University

- People from Greenock

- 1736 births

- 1819 deaths

- 18th-century Scottish people

- 19th-century Scottish people

- Members of the Lunar Society