Chromatography

Chromatography (from Greek χρώμα:chroma, color and γραφειν:graphein to write) is the collective term for a set of laboratory techniques for the separation of mixtures. It involves passing a mixture dissolved in a "mobile phase" through a stationary phase, which separates the analyte to be measured from other molecules in the mixture based on differential partitioning between the mobile and stationary phases. Subtle differences in compounds partition coefficient results in differential retention on the stationary phase and thus changing the separation.

Chromatography may be preparative or analytical. The purpose of preparative chromatography is to separate the components of a mixture for further use (and is thus a form of purification). Analytical chromatography is done normally with smaller amounts of material and is for measuring the relative proportions of analytes in a mixture. The two are not mutually exclusive.

History

The history of chromatography begins during the mid-19th century. Chromatography, literally "color writing", was used—and named— in the first decade of the 20th century, primarily for the separation of plant pigments such as chlorophyll. New types of chromatography developed during the 1930s and 1940s made the technique useful for many types of separation process.

Some related techniques were developed during the 19th century (and even before), but the first true chromatography is usually attributed to Russian botanist Mikhail Semyonovich Tsvet, who used columns of calcium carbonate for separating plant pigments during the first decade of the 20th century during his research of chlorophyll.

Chromatography became developed substantially as a result of the work of Archer John Porter Martin and Richard Laurence Millington Synge during the 1940s and 1950s. They established the principles and basic techniques of partition chromatography, and their work encouraged the rapid development of several types of chromatography method: paper chromatography, gas chromatography, and what would become known as high performance liquid chromatography. Since then, the technology has advanced rapidly. Researchers found that the main principles of Tsvet's chromatography could be applied in many different ways, resulting in the different varieties of chromatography described below. Simultaneously, advances continually improved the technical performance of chromatography, allowing the separation of increasingly similar molecules.

Chromatography terms

- The analyte is the substance that is to be separated during chromatography.

- Analytical chromatography is used to determine the existence and possibly also the concentration of analyte(s) in a sample.

- A bonded phase is a stationary phase that is covalently bonded to the support particles or to the inside wall of the column tubing.

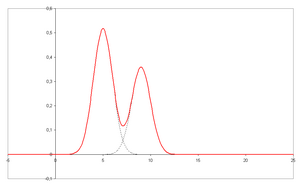

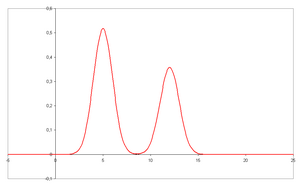

- A chromatogram is the visual output of the chromatograph. In the case of an optimal separation, different peaks or patterns on the chromatogram correspond to different components of the separated mixture.

- Plotted on the x-axis is the retention time and plotted on the y-axis a signal (for example obtained by a spectrophotometer, mass spectrometer or a variety of other detectors) corresponding to the response created by the analytes exiting the system. In the case of an optimal system the signal is proportional to the concentration of the specific analyte separated.

- A chromatograph is equipment that enables a sophisticated separation e.g. gas chromatographic or liquid chromatographic separation.

- Chromatography is a physical method of separation in which the components to be separated are distributed between two phases, one of which is stationary (stationary phase) while the other (the mobile phase) moves in a definite direction.

- The effluent is the mobile phase leaving the column.

- An immobilized phase is a stationary phase which is immobilized on the support particles, or on the inner wall of the column tubing.

- The mobile phase is the phase which moves in a definite direction. It may be a liquid (LC and CEC), a gas (GC), or a supercritical fluid (supercritical-fluid chromatography, SFC). A better definition: The mobile phase consists of the sample being separated/analyzed and the solvent that moves the sample through the column. In the case of HPLC the mobile phase consists of a non-polar solvent(s) such as hexane in normal phase or polar solvents in reverse phase chromotagraphy and the sample being separated. The mobile phase moves through the chromatography column (the stationary phase) where the sample interacts with the stationary phase and is separated.

- Preparative chromatography is used to purify sufficient quantities of a substance for further use, rather than analysis.

- The retention time is the characteristic time it takes for a particular analyte to pass through the system (from the column inlet to the detector) under set conditions. See also: Kovat's retention index

- The sample is the matter analyzed in chromatography. It may consist of a single component or it may be a mixture of components. When the sample is treated in the course of an analysis, the phase or the phases containing the analytes of interest is/are referred to as the sample whereas everything out of interest separated from the sample before or in the course of the analysis is referred to as waste.

- The solute refers to the sample components in partition chromatography.

- The solvent refers to any substance capable of solubilizing other substance, and especially the liquid mobile phase in LC.

- The stationary phase is the substance which is fixed in place for the chromatography procedure. Examples include the silica layer in Chromatography#Thin layer chromatography Submitted by James Nguyen

Techniques by chromatographic bed shape

Column chromatography

Column chromatography is a separation technique in which the stationary bed is within a tube. The particles of the solid stationary phase or the support coated with a liquid stationary phase may fill the whole inside volume of the tube (packed column) or be concentrated on or along the inside tube wall leaving an open, unrestricted path for the mobile phase in the middle part of the tube (open tubular column). Differences in rates of movement through the medium are calculated to different retention times of the sample.[1]

In 1978, W. C. Still introduced a modified version of column chromatography called flash column chromatography (flash).[2][3] The technique is very similar to the traditional column chromatography, except for that the solvent is driven through the column by applying positive pressure. This allowed most separations to be performed in less than 20 minutes, with improved separations compared to the old method. Modern flash chromatography systems are sold as pre-packed plastic cartridges, and the solvent is pumped through the cartridge. Systems may also be linked with detectors and fraction collectors providing automation. The introduction of gradient pumps resulted in quicker separations and less solvent usage.

In expanded bed adsorption, a fluidized bed is used, rather than a solid phase made by a packed bed. This allows omission of initial clearing steps such as centrifugation and filtration, for culture broths or slurries of broken cells.

Planar chromatography

Planar chromatography is a separation technique in which the stationary phase is present as or on a plane. The plane can be a paper, serving as such or impregnated by a substance as the stationary bed (paper chromatography) or a layer of solid particles spread on a support such as a glass plate (thin layer chromatography). Different compounds in the sample mixture travel different distances according to how strongly they interact with the stationary phase as compared to the mobile phase. The specific Retardation factor (Rf) of each chemical can be used to aid in the identification of an unknown substance.

Paper chromatography

Paper chromatography is a technique that involves placing a small dot or line of sample solution onto a strip of chromatography paper. The paper is placed in a jar containing a shallow layer of solvent and sealed. As the solvent rises through the paper, it meets the sample mixture which starts to travel up the paper with the solvent. This paper is made of cellulose, a polar substance, and the compounds within the mixture travel farther if they are non-polar. More polar substances bond with the cellulose paper more quickly, and therefore do not travel as far.

Thin layer chromatography

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) is a widely employed laboratory technique and is similar to paper chromatography. However, instead of using a stationary phase of paper, it involves a stationary phase of a thin layer of adsorbent like silica gel, alumina, or cellulose on a flat, inert substrate. Compared to paper, it has the advantage of faster runs, better separations, and the choice between different adsorbents. For even better resolution and to allow for quantification, high-performance TLC can be used.

Displacement Chromatography

The basic principle of displacement chromatography is: A molecule with a high affinity for the chromatography matrix (the displacer) will compete effectively for binding sites, and thus displace all molecules with lesser affinities.[4] There are distinct differences between displacement and elution chromatography. In elution mode, substances typically emerge from a column in narrow, Gaussian peaks. Wide separation of peaks, preferably to baseline, is desired in order to achieve maximum purification. The speed at which any component of a mixture travels down the column in elution mode depends on many factors. But for two substances to travel at different speeds, and thereby be resolved, there must be substantial differences in some interaction between the biomolecules and the chromatography matrix. Operating parameters are adjusted to maximize the effect of this difference. In many cases, baseline separation of the peaks can be achieved only with gradient elution and low column loadings. Thus, two drawbacks to elution mode chromatography, especially at the preparative scale, are operational complexity, due to gradient solvent pumping, and low throughput, due to low column loadings. Displacement chromatography has advantages over elution chromatography in that components are resolved into consecutive zones of pure substances rather than “peaks”. Because the process takes advantage of the nonlinearity of the isotherms, a larger column feed can be separated on a given column with the purified components recovered at significantly higher concentrations.

Techniques by physical state of mobile phase

Gas chromatography

Gas chromatography (GC), also sometimes known as Gas-Liquid chromatography, (GLC), is a separation technique in which the mobile phase is a gas. Gas chromatography is always carried out in a column, which is typically "packed" or "capillary" (see below) .

Gas chromatography (GC) is based on a partition equilibrium of analyte between a solid stationary phase (often a liquid silicone-based material) and a mobile gas (most often Helium). The stationary phase is adhered to the inside of a small-diameter glass tube (a capillary column) or a solid matrix inside a larger metal tube (a packed column). It is widely used in analytical chemistry; though the high temperatures used in GC make it unsuitable for high molecular weight biopolymers or proteins (heat will denature them), frequently encountered in biochemistry, it is well suited for use in the petrochemical, environmental monitoring, and industrial chemical fields. It is also used extensively in chemistry research.

Liquid chromatography

Liquid chromatography (LC) is a separation technique in which the mobile phase is a liquid. Liquid chromatography can be carried out either in a column or a plane. Present day liquid chromatography that generally utilizes very small packing particles and a relatively high pressure is referred to as high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

In the HPLC technique, the sample is forced through a column that is packed with irregularly or spherically shaped particles or a porous monolithic layer (stationary phase) by a liquid (mobile phase) at high pressure. HPLC is historically divided into two different sub-classes based on the polarity of the mobile and stationary phases. Technique in which the stationary phase is more polar than the mobile phase (e.g. toluene as the mobile phase, silica as the stationary phase) is called normal phase liquid chromatography (NPLC) and the opposite (e.g. water-methanol mixture as the mobile phase and C18 = octadecylsilyl as the stationary phase) is called reversed phase liquid chromatography (RPLC). Ironically the "normal phase" has fewer applications and RPLC is therefore used considerably more.

Specific techniques which come under this broad heading are listed below. It should also be noted that the following techniques can also be considered fast protein liquid chromatography if no pressure is used to drive the mobile phase through the stationary phase. See also Aqueous Normal Phase Chromatography.

Affinity chromatography

Affinity chromatography[5] is based on selective non-covalent interaction between an analyte and specific molecules. It is very specific, but not very robust. It is often used in biochemistry in the purification of proteins bound to tags. These fusion proteins are labeled with compounds such as His-tags, biotin or antigens, which bind to the stationary phase specifically. After purification, some of these tags are usually removed and the pure protein is obtained.

Supercritical fluid chromatography

Supercritical fluid chromatography is a separation technique in which the mobile phase is a fluid above and relatively close to its critical temperature and pressure.

Techniques by separation mechanism

Ion exchange chromatography

Ion exchange chromatography uses ion exchange mechanism to separate analytes. It is usually performed in columns but can also be useful in planar mode. Ion exchange chromatography uses a charged stationary phase to separate charged compounds including amino acids, peptides, and proteins. In conventional methods the stationary phase is an ion exchange resin that carries charged functional groups which interact with oppositely charged groups of the compound to be retained. Ion exchange chromatography is commonly used to purify proteins using FPLC.

Size exclusion chromatography

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) is also known as gel permeation chromatography (GPC) or gel filtration chromatography and separates molecules according to their size (or more accurately according to their hydrodynamic diameter or hydrodynamic volume). Smaller molecules are able to enter the pores of the media and, therefore, take longer to elute, whereas larger molecules are excluded from the pores and elute faster. It is generally a low-resolution chromatography technique and thus it is often reserved for the final, "polishing" step of a purification. It is also useful for determining the tertiary structure and quaternary structure of purified proteins, especially since it can be carried out under native solution conditions.

Special techniques

Reversed-phase chromatography

Reversed-phase chromatography is an elution procedure used in liquid chromatography in which the mobile phase is significantly more polar than the stationary phase.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2008) |

Two-dimensional chromatography

In some cases, the chemistry within a given column can be insufficient to separate some analytes. It is possible to direct a series of unresolved peaks onto a second column with different physico-chemical (Chemical classification) properties. Since the mechanism of retention on this new solid support is different from the first dimensional separation, it can be possible to separate compounds that are indistinguishable by one-dimensional chromatography.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2008) |

Simulated moving-bed chromatography

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2008) |

Pyrolysis gas chromatography

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2008) |

Fast protein liquid chromatography

Fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) is a term applied to several chromatography techniques which are used to purify proteins. Many of these techniques are identical to those carried out under high performance liquid chromatography, however use of FPLC techniques are typically for preparing large scale batches of a purified product.

Countercurrent chromatography

Countercurrent chromatography (CCC) is a type of liquid-liquid chromatography, where both the stationary and mobile phases are liquids. It involves mixing a solution of liquids, allowing them to settle into layers and then separating the layers.

Chiral chromatography

Chiral chromatography involves the separation of stereoisomers. In the case of enantiomers, these have no chemical or physical differences apart from being three-dimensional mirror images. Conventional chromatography or other separation processes are incapable of separating them. To enable chiral separations to take place, either the mobile phase or the stationary phase must themselves be made chiral, giving differing affinities between the analytes. Chiral chromatography HPLC columns (with a chiral stationary phase) in both normal and reversed phase are commercially available.

See also

- Aqueous Normal Phase Chromatography

- Multicolumn countercurrent solvent gradient purification (MCSGP)

- Purnell equation

References

- ^ IUPAC Nomenclature for Chromatography IUPAC Recommendations 1993, Pure & Appl. Chem., Vol. 65, No. 4, pp.819-872, 1993.

- ^ Still, W. C.; Kahn, M.; Mitra, A. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43(14), 2923-2925. doi:10.1021/jo00408a041

- ^ Laurence M. Harwood, Christopher J. Moody. Experimental organic chemistry: Principles and Practice (Illustrated edition ed.). pp. 180–185.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Text "ISBN 0632020172" ignored (help); Text "ISBN 978-0632020171" ignored (help); Text "Number of Pages: 790" ignored (help); Text "Publisher: WileyBlackwell" ignored (help); Text "Publishing Date: 13 Jun 1989" ignored (help) - ^ Displacement Chromatography 101. Sachem, Inc. Austin, TX 78737

- ^ Pascal Bailon, George K. Ehrlich, Wen-Jian Fung and Wolfgang Berthold, An Overview of Affinity Chromatography, Humana Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-89603-694-9, ISBN 978-1-60327-261-2.

External links

- IUPAC Nomenclature for Chromatography

- ChromediaOn line database and community for chromatography practitioners (paid subscription required)

- Reversed phase chromatography article (dutch)

- Library 4 Science: Chrom-Ed Series

- Overlapping Peaks Program - Learning by Simulations

- Chromatography Videos - MIT OCW - Digital Lab Techniques Manual

- Chromatography Equations Calculators - MicroSolv Technology Corporation