Romance comics

| Romance comics | |

|---|---|

A typical Victor Fox title of the 1950s, My Story True Romances in Pictures | |

| Publishers | |

| Publications |

|

Romance comics (sometimes love comics) is a comics genre depicting romantic love and its attendant complications such as jealousy, marriage, divorce, betrayal, and heartache. The term is generally associated with an American comic books genre published through the first three decades of the Cold War (1947–1977). Romance comics of the period typically featured dramatic scripts about the love lives of older high school teens and young adults, with accompanying artwork depicting an urban or rural America contemporaneous with publication.

The origins of romance comics lie in the years immediately following World War II when adult comics readership increased and superheroes were dismissed as passé. Influenced by the pulps, radio soap operas, newspaper comic strips such as Mary Worth, and adult confession magazines, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby created the flagship romance comic book Young Romance and launched it in 1947 to resounding success. By the early 1950s, dozens of romance titles from major comics publishers were on the newsstands and drug store racks.

With the implementation of the Comics Code in 1954, romance comics publishers self-censored any material that might be interpreted as controversial and opted to play it safe with stories focusing on traditional patriarchial concepts of female behavior, gender roles, love, sex, and marriage. The genre fell into decline and disrepute during the sexual revolution, and the genre's Golden Age came to an end when Young Romance and its companion Simon and Kirby title Young Love ceased publication in 1975 and 1977 respectively.

In the new millenium, a few publishers flirted with the genre in various ways, including manga-styled romance comics based on Harlequin novels and Golden Age classics revamped with snarky dialogue.

Origin

American romance comics had their origin in the years immediately following World War II when hip comics readers found crime-busting superheroes in tights and trunks a thing of the past. Adult comics readership had grown during the war years and returning servicemen wanted sex, violence, and humor in their comics. The genre took its immediate inspiration from the romance pulps, confession magazines such as True Story, radio soap operas, and newspaper comic strips that focused on love, domestic strife, and heartache, such as Rex Morgan, M.D. and Mary Worth.[1]

Joe Simon and Jack Kirby

Aside from the one-time publication of Mary Worth comic-strip reprints, romance as a comic-book genre was the brainchild of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, two comics artists known for their superheroes, such as Captain America, and their kid gangs, such as the Young Allies. Simon was serving in the United States Coast Guard when he got the idea for romance comics: "I noticed there were so many adults, the officers and men, the people in the town, reading kid comic books. I felt sure there should be an adult comic book." Simon developed the idea with sample covers and title pages and called his production Young Romance, the "Adult Comic Book". Simon later noted he chose the love genre because "it was about the only thing that hadn't been done."[1]

After the service, Simon teamed-up with his former partner Jack Kirby, and the two developed a first-issue mock-up of Young Romance.[2] Bill Draut and other artists participated, with Simon and Kirby producing the scripts because "we couldn't afford writers." Rather than the dramatic comic strips, Simon took his inspiration from the darker-toned confession magazines such as True Story from Macfadden Publications.[1]

The finished book was delivered to Crestwood general manager Maurice Rosenfeld. Crestwood owners Mike Bleir and Teddy Epstein were enthusiastic and worked out a 50% arrangement with the creators.[2] Profit sharing was unusual at the time, and Kirby later noted he and his partner were, in fact, the first to receive percentages.[1]

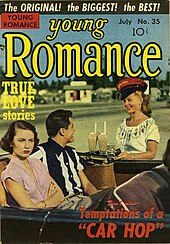

The first issue of Young Romance was cover-dated September-October 1947, and beneath the title bore the tagline "Designed For The More ADULT Readers of Comics". The title sold 92% of its print run. With the third issue, Crestwood increased the print run to triple the initial number of copies.[3] Circulation jumped to 1,000,000 copies per title. Initially published bimonthly, Young Romance quickly became a monthly title and generated the spin-off, Young Love — together the two titles sold two million copies per month.[2] Kirby noted the books "made millions."[1] The two titles were later joined by Young Brides and In Love, the latter "featuring full-length romance stories".[3]

Subsequent publications

Timely/Marvel brought the second romance title to newsstands with My Romance in August 1948, and Fox Feature Syndicate released the third title, My Life, in September 1948. Fawcett Publications followed with Sweethearts (the first monthly title) in October 1948.[4] By 1950, more than 150 romance titles were on the newsstands from Quality Comics, Avon, Lev Gleason Publications, and DC Comics. Fox Feature Syndicate published over two dozen love comics with 17 featuring "My" in the title—My Desire, My Secret, My Secret Affair, et al.[1]

Artists working romance comics during the period included Matt Baker, Frank Frazetta, Everett Kinstler, Jay Scott Pike, John Romita, Sr., Leonard Starr, Alex Toth, and Wally Wood. Marie Severin once was given the job at Marvel of updating the clothing from old 1960s romance comic stories for publication in the 1970s.[5]

Romance comics did impressively well commercially, but negatively impacted the sales of superhero comics and confession magazines. True Story admitted their sales were being hurt by the upstart romance comics. In the August 22, 1949 issue of Time, a report indicated that love comics were "outselling all others, even the blood and thunder variety [...] For pulp magazines the moral was even clearer: no matter how low their standards for fiction, the comics could find lower ones."[1]

By 1954, parents, school teachers, clergymen, and others taking an interest in the welfare of children, believed comic books were a significant contributor to the epidemic of juvenile deliquency sweeping America. While romance comics did not bear the contempt and scrutiny heaped upon crime comics and horror comics, the genre did provoke comment from child specialist, Dr. Frederic Wertham. In his book, Seduction of the Innocent, Wertham deplored not only the "mushiness" of the romance comics, but their "social hypocrisy", "false sentiments", "cheapness", and "titillation". He claimed the genre gave female readers a false image of love and feelings of physical inferiority.[6]

Decline and Golden Age demise

Following the implementation of the Comics Code in 1954, publishers of romance comics self-censored the content of their publications, making the stories bland and innocent with the emphasis on traditional patriarchial concepts of women's behavior, gender roles, domesticity, and marriage. When the sexual revolution questioned the values promoted in romance comics, along with the decline in comics in general, romance comics began their slow fade. DC Comics, Marvel Comics and Charlton Comics carried a few romance titles into the middle 1970s, but the genre never regained the level of popularity it once enjoyed. The heyday of romance comics came to an end with the last issues of Young Romance and Young Love in the middle 1970s.[4][5][7]

Charlton and DC artist and editor Dick Giordano stated in 2005: "[G]irls simply outgrew romance comics [...] [The content was] too tame for the more sophisticated, sexually liberated, women's libbers [who] were able to see nudity, strong sexual content, and life the way it really was in other media. Hand holding and pining after the cute boy on the football team just didn't do it anymore, and the Comics Code wouldn't pass anything that truly resembled real-life relationships."[4]

Aftermath

A few publishers in the 2000s began again producing romance comics. Dark Horse Comics, in conjunction with Harlequin Enterprises, published a new line of romance manga comics, with adaptations of previously published romance novels.[8] The influx of manga into North America carried with it an interest in a wider variety of genre, including romance and erotica, aimed at a young female audience. Harlequin hopes that the manga-styled romance comics will reach a younger audience than the audience of romance novels.[9]

In June 2005, Arrow Publications launched a line of romance webcomics, which are similar in form to the comics of the 1960s and 1970s.[10] In 2006, Adhouse Books published Project: Romantic, an anthology of contemporary romance comics. In 2007, Marvel Comics published several issues of Marvel Romance Redux, an affectionate revamp of their old romance titles, taking pages from them and replacing them with snarky dialogue.

Analysis

Romance comic books upheld the Cold War ideology of the American way of life. Central to this ideology was the middle class American family as the symbol of affluence, consumption, and the spiritual fulfillment the American way of life promised and so, girls of the era were encouraged to grow up early and assume the roles of loving wives, concerned mothers, and happy homemakers. Female promiscuity, career ambition, and independence degraded the American ideal.[6]

The basic formula for the romance comic story was established in Simon and Kirby's Young Romance of 1947. Other scriptwriters, artists, and publishers simply tweaked the formula from time to time for a bit of variety. Stories were overwhelmingly written by men from the male perspective, and were narrated by fictional female protagonists who described the dangers of female independence and touted the virtues of domesticity.[6]

Women were depicted as incomplete without a male, but the genre discouraged the aggressive pursuit of men or any behaviors that smacked of promiscuity. In one story, the female protagonist kisses a boy in public and is thereafter labelled a "manchaser" to be avoided by decent boys. An advice page in one issue blamed female public behavior, flirting, and flashy dress for attracting the wrong sort of boys. Female readers were advised to maintain a passive gender role, or dreams of romance, marriage, and happiness could be kissed good-bye.[6]

The romance comic books made domestic stability obviously preferable to passion and thrills. Those women who sought such exciting outlets in comics stories were depicted as suffering many disappointments before settling down (finally) to quiet home lives. In "Back Door Love", the protagonist learns that the man she is infaturated with is a "rat". She degrades herself to be with him, but comes to her senses and eventually marries an unexciting man who provides her with stability. In "I Ran Away with a Truck Driver", the small town heroine runs off with a handsome truck driver who promises her thrills but, in the end, robs her and leaves her stranded in Chicago. She returns home, chastened and wiser, to share the company of a decent local boy.[6]

Careers were discouraged. Working women were depicted as unhappy and unfulfilled because careers complicated relationships and limited chances for marriage. In one story, a female advertising executive makes it clear to her boyfriend her career comes first. After he leaves her in disgust, she realizes she does love him and drops her career to become a happy wife and mother. Romance comics made it clear that men were not attracted to working women, were bored with intelligent women, and preferred domestic homebodies.[6]

Men, on the other hand, were depicted as naturally independent and women were expected to accomodate such men even if things appeared a bit suspicious. In one story, a wife suspects her husband of infidelity and leaves him only to discover later she was wrong (according to him). She returns to her husband and draws the conclusion that "love means faith in the face of any evidence, no matter how overwhelming".[6]

As real world young men went off to the Korean War, romance comics emphasized the importance of women waiting patiently, unflinchingly, and chastely for their return. In one war-colored tale, a woman who loves to social dance remains faithful to her boyfriend and marries him even though he loses a leg in the war. The two will never dance together again, but it is clear that her sacrifice is as patriotic as that of her lover.[6]

Romance comics plots were typically formulaic with Emily Bronte's Wuthering Heights a seeming inspiration. Many stories of the genre featured a young heroine torn between two suitors: one, a wild Heathcliff type who promised thrills and threatened heartbreak, and the other, a stolid but dull Edgar Linton type who oozed respectability, security, and social acceptance. Adolescent girls could harmlessly indulge their bad boy fantasies in such stories but, in truth, romance comics tried to be democratic in their depiction of bad boys, giving them a softer side and not depicting them as irredeemably bad.[11]

Some plots depicted young women challenging social conventions and the patriarchal authority of fathers and boyfriends. Parental concern found expression in romance comics for what were considered dangerous youth cultural artifacts like rock and roll. In "There's No Love in Rock and Roll" (1956), a defiant teen dates a rock and roll-loving boy but drops him for one who likes traditional adult music—much to her parents' relief.[4] Teen rebellion stories such as "I Joined a Teen-Age Sex Club", "Thrill Seekers' Weekend", and "My Mother was My Rival" were dismissed as "girls' stuff" at a time when crime, horror, and other violent comics were being regarded with suspicion by those concerned with juvenile deliquency and the welfare of the young.[11]

Dating, love triangles, jealousy and other romance-related themes had been a part of teen humor comics before the romance genre swept newsstands. Comics characters such as Archie, Reggie, Jughead, Betty, and Veronica and the kids at Riverdale High School being the principal exponents of teen romance. Young Romance, Young Love and their imitators differed from the teen humor comics in that they aspired to realism, using first person narration to create the illusion of verisimilitude, a changing cast of characters in self-contained stories, and heroines in their late teens or early twenties who were closer to the target audience in age than teen humor characters.[12]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goulart, Ron (2001). Great American Comic Books. Publications International, Ltd. pp. 161, 169–172. ISBN 0-7853-5590-1.

- ^ a b c Simon, Joe (2003). The Comic Book Makers. Vanguard Publications. pp. 123–125. ISBN 1887591354.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Howell, Richard. Real Love: The Best of the Simon and Kirby Romance Comics 1940s-1950s. Eclipse Books. pp. Introduction.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dste=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Nolan, Michelle (2008). Love on the Racks: A History of American Romance Comics. McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 30, 210. ISBN 978-0-7864-3519-7. Cite error: The named reference "Nolan" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "Profiles: Romance Comics". The Quarter Bin. January 7, 2001. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wright, Bradford W. (2003). Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 127–133, 160. ISBN 0-80187450-5.

- ^ Miller, Jenny (2001). "A Very Brief History of Romance Comics". Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "Press Releases: Harlequin Ginger Blossom Manga". Dark Horse Comics, Inc. May 16, 2005. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ Glazer, Sarah (September 18, 2005). "Manga for Girls". The New York Times. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Arrow Publications Presents: MyRomanceStory". Arrow Publications LLC. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ a b Hajdu, David (2008). The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. pp. 154–174. ISBN 978-0-374-18767-5.

- ^ Mitchell, Claudia A. (2008). Girl Culture. Greenwood Press. pp. 508–509. ISBN 9780313339080.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)