High Speed 2

| High Speed 2 | |

|---|---|

| Overview | |

| Status | Proposed for 2025 |

| Locale | United Kingdom (Greater London, West Midlands initial) |

| Termini | |

| Stations | 4 (initial) |

| Service | |

| Type | High-speed railway |

| System | National Rail |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | Standard gauge 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) |

| Operating speed | Up to 250 mph (400 km/h)[n 1] |

High Speed 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

As of October 2023

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Original plan, pre-2021

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

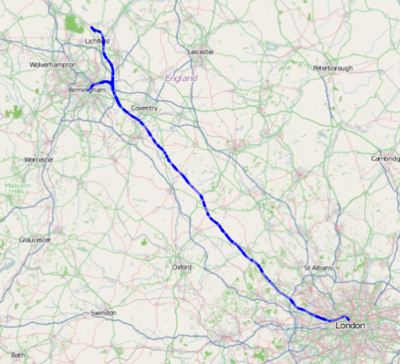

High Speed 2 (HS2) is a proposed high-speed railway between London and the Midlands, the North of England, and the central belt of Scotland, being developed by High Speed Two Limited, a company established by the British government. It would take the form of a "Y" shaped route, with a trunk from London to Birmingham, and then two spurs, one to Manchester, and the other to Leeds via the East Midlands. The project would be developed in stages, with the London to Birmingham portion being the first. There would be no intermediate stopping points between London and rural Solihull.

High-speed rail is supported in principle by the three main United Kingdom political parties; there is, however, debate about which cities should be served, and on the environmental performance and impact of high-speed rail.[1] If approved, construction would begin in 2017 with the first trains running by 2025.[2] At present, the only high-speed route in Britain is High Speed 1 (the Channel Tunnel Rail Link).

The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government formed in May 2010 stated in its initial programme for government its commitment to creating a high speed rail network.[3]

History

The Department for Transport published a document in January 2009 giving details of various options for new-build high-speed rail[n 2] and concluded that the most appropriate initial route for a new line was from London to the West Midlands.[n 3]

High Speed Two Limited

In January 2009, the government established a company, High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd), chaired by Sir David Rowlands[n 4] with the remit of examining the case for a new British high speed line and presenting a potential route between London and the West Midlands;[n 5] which had been identified by the DfT as the initial stage to be built of a new high speed network.[n 6] The government report suggested that utltimately the line could be extended to reach Scotland.[n 7]

Drawing on consultation produced for the Department for Transport (DfT) and Network Rail, HS2 Ltd would provide advice on options for a Heathrow International interchange station, access to central London, connectivity with HS1 and the existing rail network, and financing and construction,[n 8] and report to government on the first stage by the end of 2009.[n 9]

In August 2009, Network Rail published its own study outlining its proposals for the expansion of the railway network which included a new high-speed rail line between London and Glasgow/Edinburgh, following a route through the West Midlands and the North-West of England.[4]

For the HS2 report, a route was investigated to an accuracy of 0.5 metres (18 in).[5] In December 2009, HS2 handed its report to the government. The study investigated the possibility of links to Heathrow Airport, connections to Crossrail, the Great Western Main Line, and the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (HS1).

On 11 March 2010, the High Speed 2 report and supporting studies were published, together with the government's command paper on high-speed rail.[6][7]

Conservative - Liberal Democrat coalition government

The Conservative - Liberal Democrat coalition, formed in May 2010, has begun a review of HS2 plans inherited from the previous government. The Conservative Party, whilst in Opposition, backed the idea of a high-speed terminus at London St Pancras with a direct link to Heathrow Airport[8] and has a policy to connect London, Manchester, Leeds and Birmingham with Heathrow by high-speed rail with construction starting in 2015.[9] In March 2010, Theresa Villiers stated "The idea that some kind of Wormwood Scrubs International station is the best rail solution for Heathrow is just not credible."[10]

The Secretary of State for Transport, Philip Hammond, asked Lord Mawhinney, a former Conservative Transport Secretary, to conduct an urgent review of the proposed route. The coalition government wished the high-speed line to be routed via Heathrow Airport, an idea rejected in the most recent proposal published by HS2 Ltd.[11]

Lord Mawhinney's conclusions contradicted Ms Villiers' view and Conservative policy in Opposition, stating that HS2 should not go to Heathrow Airport unless it goes further than Birmingham. He stated that Heathrow should be served, via a loop, only when the line reaches the northern regions of England. Routeing the line only via Heathrow would add seven minutes to the journey time of all services.[12]

In December 2008 an article in the The Economist noted the increasing political popularity of high-speed rail in Britain as a solution to transport congestion, and as an alternative to unpopular schemes such as road-tolls and runway expansion, but concluded that its future would depend on it being commercially viable.[13] In November 2010, Philip Hammond dispelled this assumption, stating that government support for HS2 did not require it to be financially viable:

If we used financial accounting we would never have any public spending, we would build nothing ... Financial accounting would strike a dagger through the whole case for public sector investment.[14]

Route

London to the West Midlands

As proposed in March 2010, the line would run from London Euston, mainly in tunnel, to an interchange with Crossrail, west of Paddington, thence along the New North Main Line (Acton-Northolt Line) past West Ruislip alongside the Chiltern Main Line with a four-kilometre viaduct over the Grand Union Canal and River Colne, from the M25 to Amersham in a new 9.6 km tunnel. After emerging from the tunnel, the line would run parallel to the existing A413 road and London - Aylesbury line corridor, through the 47 km wide Chiltern Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty passing close by Great Missenden to the East, alongside Wendover immediately to the West, then on to Aylesbury. After Aylesbury, the line would run alongside the Aylesbury to Verney Junction line, joining it north of Quainton Road and then striking out to the north-west across open countryside through North Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire, South Northamptonshire, Warwickshire and Staffordshire.[citation needed] A number of alignments have been studied, and in September 2010 HS2 Ltd set out recommendations for altering the course at certain locations.[15]

Heathrow access

Whilst in Opposition, the Conservatives stated that in government, they would "support proposals along the lines put forward by engineering firm, Arup, for a new Heathrow rail hub" [16] Arup's Heathrow Hub Arup Submission to HS2, stated that a 200-acre (0.81 km2) site at Iver, north-east of the intersection of the M25 and M4, could house a railway station of 12 or more platforms, as well as a coach and bus station and an airport terminal. The high-speed line would then follow a different route to Birmingham, running parallel to existing motorways and railways as with HS1 in Kent.

According to Lord Mawhinney, the Heathrow station should be directly beneath Heathrow Central station (not at Iver, see Heathrow Hub) and the London terminus for HS2 should at Old Oak Common, not Euston.

West Midlands to the North

Less studied are the routes of any possible extensions from Birmingham to Manchester and to Sheffield and Leeds which would allow connections to the North of England and Scotland. Transport Secretary Philip Hammond announced that the route preferred by the government is the so-called "Y" route with separate branches to Manchester and Leeds.[17]

The route to the West Midlands would be the first stage of a line to Scotland,[n 10] and passengers travelling to or from Scotland would be able to use through trains with a saving of 45 minutes from day one.[18] If approved, construction would begin in 2017, with the first trains running by 2025.[19]

Connection to other lines

High Speed 1

Whether and how High Speed 2 should connect to High Speed 1 has not yet been decided or funded. The government command paper says:

... the new British high speed rail network should be connected to the wider European high speed rail network via High Speed One and the Channel Tunnel, subject to cost and value for money. This could be achieved through either or both of a dedicated rapid transport system linking Euston and St Pancras and a direct rail link to High Speed One.[n 11]

The engineering study conducted by Arup for HS2 Ltd costed a "classic speed" GC loading gauge direct rail link at £458m (single track) or £812m (double track). The connection would be from Old Oak Common to the High Speed 1 St Pancras portal, via tunnel and the North London Line. A double-track high-speed connection would cost £3.6bn.[20]

The High Speed 2 report recommended that, if a direct rail link is built, it should be the classic-speed, double-track option.[21]

West Coast Main Line in Staffordshire

HS2 would pass Lichfield without stopping, and connect to the West Coast Main Line well to the north of Wolverhampton.

Journey times

The HS2 Ltd report gave journey times for some destinations, allowing a degree of 'before and after' comparison.[n 12][22][23][24] Because it would serve only a very small subset of destinations, use of existing 'classic' services would be an element of many High Speed 2 journeys.

| London to/from... | Current timings on existing lines | Proposed (with HS2 completion to Birmingham) | Proposed (with HS2 completion to Manchester and Leeds) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birmingham | 1 hour 24 minutes | 49 minutes | |

| Coventry | 1 hour 1 minute | 1 hour 1 minute† | |

| Oldbury | 1 hour 34 minutes | 1 hour 23 minutes‡ | |

| Wolverhampton | 1 hour 43 minutes | 1 hour 37 minutes‡ | |

| Manchester | 2 hours 8 minutes | 1 hour 40 minutes | 1 hour 20 minutes |

| Liverpool | 2 hours 8 minutes | 1 hour 50 minutes | 1 hour 36 minutes |

| Leeds | 2 hours 20 minutes | 2 hours 20 minutes | 1 hour 20 minutes |

| Edinburgh | 4 hours 30 minutes | 4 hours 30 minutes | 3 hours 30 minutes |

| Glasgow | 4 hours 31 minutes | 4 hours | 3 hours 30 minutes |

|

† Using HS2 for a Coventry - London rail journey would require changing twice (at Birmingham International and Birmingham Interchange): the figure given is for the existing line via Milton Keynes. | |||

Proposed stations

London to Birmingham

Central London

Under the March 2010 scheme, HS2 would start from an expanded London Euston. A rapid transit link between Euston and London St Pancras might be provided. The command paper suggested that the connection with Crossrail at Old Oak Common in West London would mitigate the extra burden on Euston.

However, the review by former Conservative Transport Secretary Lord Mawhinney recommended that High Speed 2 should terminate at Old Oak Common, not Euston.[12] He questioned the sense of having HS2 terminate at Euston and High Speed 1 at St Pancras, with no 'connection' between them.[12]

West London

The March 2010 report proposed that all trains would stop at a west London "Crossrail interchange" near Old Oak Common between Paddington and Acton Main Line stations, with connections for Crossrail, Heathrow Express and services on the Great Western Main Line to Heathrow Airport, Reading, South West England and South Wales. The station might also have connections with London Overground and Southern services on the North London and West London Lines and also with London Underground's Central Line.[n 13]

Lord Mawhinney recommended that High Speed 2 should terminate at Old Oak Common because of its good connections and in order to save the cost of tunnelling to Euston.[12]

Bickenhill ("Birmingham Interchange")

The March 2010 report proposed that a new "Birmingham Interchange" station would be built in rural Solihull, on the other side of the M42 motorway from the National Exhibition Centre, Birmingham International Airport and Birmingham International Station.[n 14] The interchange would be connected by a people mover to the other sites; the AirRail Link people mover already operates between Birmingham International station and the airport.

According to Birmingham Airport's chief executive Paul Kehoe, HS2 is a key element in ramping up the number of flights using the airport,[25] and patronage by inhabitants of London and the South-East: "it would move the airport 70 miles closer to central London, placing it somewhere near Edgware on the Northern Line". The airport operates at about half its current capacity,[25] but Birmingham City Council and transport authority Centro are backing plans for a major expansion, including a longer runway.[26][27]

Birmingham city centre

New Street station, the main station serving central Birmingham, has been described as operating at full capacity and being unable to accommodate new high-speed services. A new terminus for High Speed 2, termed "Birmingham Curzon Street" in the government's command paper[n 15] and as "Birmingham Fazeley Street" in the report produced by High Speed 2 Ltd, would be built on land between Moor Street Queensway and the site of the old Curzon Street Station. It would be reached via a spur line from a triangular junction with the "main" HS2 trunk at Coleshill.[28]

Development plans for the Eastside district and a new campus for Birmingham City University continued to be progressed, though incompatible with HS2, because the government kept the proposed route secret.[29][n 16] Centro was also wrongfooted by the choice of Fazeley Street as a terminus, with it having no Parliamentary power for its proposed city tramway extension to serve the area.

As Curzon Street/Fazeley Street terminus would not receive other services, local or regional rail passengers arriving in Birmingham would need to transfer from New Street, Snow Hill or Moor Street stations. The direct pedestrian access between the HS2 terminal site and New Street, the city's main station, entails traversing the Smallbrook Queensway "mugger's alley"[30] tunnel[31] under the Bullring shopping centre.

Beyond Birmingham

East Midlands

A new station in the East Midlands is also proposed at an unidentified site. This might take the form of a parkway station, and not be sited in Nottingham, Leicester or Derby.[32] In British usage, a parkway is station with car parking, remote from the location it is intended to serve.

Business leaders in the area supported high-speed rail coming to the East Midlands but were concerned that a parkway "would cut connecting traffic" and "negate the shorter journey times of the high-speed train itself".[32]

Development

Infrastructure

High Speed 2 Ltd.'s report uses the specifications of a high speed line built to the European structure gauge (as was High Speed 1) and conforming to European Union technical standards for interoperability for high speed rail{[n 17] (EU Directive 96/48/EC). HS2 Ltd's report assumed a GC structure gauge for passenger capacity estimations,[33] with a maximum design speed of 250 miles per hour (400 km/h).[n 18] Initially, trains would run at a maximum 225 miles per hour (362 km/h).[n 19]

Freight trains could use the line within a limited nighttime window, due to their relatively low speed. However, it would release capacity on the existing West Coast Main Line and Midland Main Line for freight.[n 20]

Signalling would be a level of the European Rail Traffic Management System using in-cab signalling, to resolve the visibility issues associated with line-side signals at speeds over 200 km/h (125 mph).

Rolling stock

HS2 mentioned two types of train:[n 21]

- 'Classic compatible' trains would be built to the British loading gauge, and could run off the high speed line onto conventional routes such as the West Coast Main Line.

- Wider and taller trains built to a European loading gauge which would be confined to the high-speed network (High Speed 1, High Speed 2, Channel Tunnel & beyond) and other lines cleared to their loading gauge).

The report also considered the possibility of gauge enhancement on non-high speed lines as an alternative to "classic compatible trains" to allow European gauge trains to run outside the high-speed network.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

HS2 Ltd claimed that because of their non-standard nature, classic-compatible trains were expected to be more expensive.[n 22]

Timeline to opening

High Speed 2 Ltd suggested[n 23] that following ministerial approval, public consultation, parliamentary approval through a hybrid bill, and detailed design, construction of the London-Birmingham section could begin in mid-2018. This is estimated to require six and a half years, with a further year to finish testing.[n 24] Reconstruction of Euston "would form the critical path for the whole programme".[n 25] Opening would be at the end of 2025.[n 26]

The command paper suggested that opening to Birmingham should be possible by the end of 2026.[n 27] The timetable included the additional work of preparing the routes to Leeds and Manchester, for approval by Parliament in the hybrid bill. Including the whole of the initial Y-shaped network in one bill would facilitate planning avoid using excessive parliamentary time.[n 28]

Perspectives

Support

A number of organisations support the HS2 project or the development of a high-speed rail network in the UK more generally. These include Greengauge 21 (a lobbying company), Railfuture (a pro-rail campaigning group), and HSR:UK (a group of Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Nottingham, and Sheffield city councils).

Alan Francis, the Green Party's transport speaker, outlined its support "in principle" for HS2[34] with the line restricted to 300 to 320 km/h to enable it to "follow existing transport corridors",[34] and changes to portions of the route, including additional tunnelling in the Chilterns.[34] It supported a different approach to central Birmingham, entailing demolition of houses in the 16 km between Berkswell station and the city centre, doubling the width of the existing railway to four tracks.[34]

The Scottish Government's policy is to engage "with the UK Government on the development of a high speed rail link to reduce journey times between Central Scotland and London to under 3 hours and provide direct services to the Continent."[35]

Opposition

Over fifty groups are known to oppose HS2 along the preferred and alternative routes, including ad hoc entities, residents' associations, and parish councils.[36] The route is also opposed by district and county councils in Greater London,[37] Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire, Warwickshire and Staffordshire.[38]. The Wildlife Trusts (a group of 47 trusts across the UK with 800,000 members) are also opposing the current proposal, stating that the former Government's policy on High Speed Rail (March 2010) "significantly underestimated the impact of the proposed route on the natural environment" [39]

To facilitate collaboration between groups, co-ordination of activities, and pooling resources and talent, the HS2 Action Alliance was formed on 7 May 2010.[40] The Alliance's primary aim is to prevent HS2 from happening; secondary aims include evaluating and minimising the impacts of HS2 on individuals, communities and the environment, and communication of facts about HS2, and its compensation scheme.[40]

Other

Organisations with noncommittal, ambiguous or dissatisfied positions include the Campaign to Protect Rural England, the National Trust, Friends of the Earth,[41] and the Campaign for Better Transport.[42] The CPRE stated that HS2 should not run at 'ultra high speeds', claiming that lower speeds would increase journey times only slightly, while allowing the line to run along existing motorways and railways, reducing intrusion.[43]

The North Staffordshire Chamber of Commerce stated that HS2 had to have a station in the county,[44] but Staffordshire County Council is opposed to HS2.[45]

The Federation of Small Businesses expressed scepticism over the need for high speed rail, stating that roads expenditure was more useful for its members,[46] and Coventry and Warwickshire chamber of commerce opined that HS2 offered no benefit to its area.[47]

Environmental and community impact

Visual impact

The visual impact of HS2 has received particular attention in the Chilterns which is designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[48]

Property demolition and land take

HS2's Birmingham stage would result in the demolition of more than 400 houses; 250 around Euston station, 20–30 between Old Oak Common and West Ruislip, a number of demolitions at Ealing, around 50 in Birmingham, and the remainder in pockets along the route.[49] This includes nine Grade II listed buildings and possibly a Grade II* listed farmhouse at Hampton in Arden.

In Birmingham, the new Curzon Gate student residence would have to be demolished [n 29] and Birmingham City University wanted a £30 million refund after the plans were revealed.[50]

Loss of wildlife habitat, and recreation space

David Lidington, MP for Aylesbury, raised concerns that the route could damage the 47 km-wide Chiltern Hills area of outstanding natural beauty, the Colne valley regional park on the outskirts of London, and other areas of green belt.[51]

HS2's preferred route would pass through the Chilterns in Buckinghamshire via the Misbourne Valley, then through a tunnel past Chalfont St Giles and Amersham, then past Wendover and Stoke Mandeville.[52] Its proposals also include another re-alignment of more than 1 kilometre (1,100 yd) of the River Tame, and construction of a 635 metres (694 yd)-long viaduct and a cutting[53] through ancient woodland at a nature reserve at Park Hall on the edge of Birmingham.[54]

Carbon emissions

In 2007, the Department for Transport commissioned a report, Estimated Carbon Impact of a New North South Line, from Booz Allen Hamilton[n 30] to investigate the likely carbon impacts associated with the construction and operation of a new rail line to either Manchester or Scotland, and the comparison with emissions from domestic air travel.

The report concluded that there were no carbon benefits in building a new line from London to Manchester. The additional carbon from a new rail route would be larger than the carbon emitted by air services.[n 31]

The High Speed Rail Command paper published in March 2010 stated that, with no reduction in aviation and no reduction in carbon intensity of electricity generation, the scheme would increase emissions by 440,000 tonnes per year.[n 32]

The Eddington Report stated "Given that domestic aviation accounts for 1.2 per cent of the UK's carbon emissions, it is unlikely that building a high-cost, energy-intensive, very high-speed train network is going to be a sensible way to reduce UK emissions".[55] A particular concern with high-speed rail is its inherently higher energy use and emissions. Energy use rises approximately with the square of speed; so trains operating at 300 km/h (1.5 times faster than conventional rail's maximum speed of 200 km/h /125 mph) will have over twice the emissions.

The Department for Transport's Delivering a sustainable railway stated, "Increasing the maximum speed from 200km/h to 350km/h leads to a 90% increase in energy consumption. In exchange, it cuts station-to-station journey times by less than 25% and door-to-door journey times by even less."[56]

Noise

HS2 Ltd stated that 21,300 dwellings would experience a noticeable increase in rail noise and 200 non-residential receptors (community; education; healthcare; and recreational/social facilities) within 300 metres of the preferred route have the potential to experience significant noise impacts.[49]

Geology and water supply

Research presented by Dr Haydon Bailey, geological adviser to the Chiltern Society, showed that HS2 tunnelling could cause long term damage to the chalk aquifer system responsible for water supply for the North Western Home Counties and North London.[57]

Compensation

The only compensation scheme for which details are available is the government's discretionary Exceptional Hardship Scheme (EHS), on which consultation closed on 17 June 2010. It is intended to compensate homeowners who have difficulty selling their home because of the HS2 route announcement, to protecting those whose property value may be seriously affected by the 'preferred route option' and who urgently need to sell.

The EHS was intended to run from about August 2010, until the route is chosen (originally estimated around the end of 2011). Homeowners may apply to the Secretary of State to buy their home, at its full market value (assuming no HS2), if all of the following criteria are met:

- Residential owner-occupier.

- Pressing need to sell. This means a change in employment location; extreme financial pressure; to accommodate enlarged family; move into sheltered accommodation; or medical condition of a family member.

- On or in 'close vicinity' of the 'preferred route' (that is mainly those who will later on be covered by statutory blight provisions).

- Have tried to sell – been on the market for at least three months with no offers within 15% of full market value (as if no HS2).

- Can demonstrate inability to sell is due to HS2.

- No prior knowledge of HS2 before acquiring the property.

Decisions on individual applications will by made by a panel of experts.[58]

The results of the consultations are not yet known. But Alison Munro, chief executive of HS2 Ltd, has stated that they are also looking at other options, including property bonds.[59] The statutory blight regime would apply to any route confirmed for a new high-speed line following the public consultations, now due to commence in 2011.[60]

HS2 Action Alliance's alternative compensation solution for property blight was presented to DfT/HS2 Ltd and Secretary of State for Transport Philip Hammond, in response to the consultation on the EHS. The Alliance also presented DfT and HS2 Ltd with a pilot study on property blight.[61]

Rationale

The intention of the HS2 scheme is to relieve congestion on the motorways, rather than replicating an existing route such as the West Coast Main Line,[n 33] and the selected route was identified as the primary national transport corridor in England, for both passenger and freight traffic by road and rail,[n 34] with the corridor being cited as having twice the size of travel market as London to the North West and six times that of London to Scotland.[n 35] The DfT cited the significant rail market share (52%) of North East England, "a region well served by efficient and reasonably fast rail services", as showing that the new line could achieve a modal shift to rail, from road and air.[n 36]

In launching the project, the DfT announced that the new High Speed 2 line between London and the West Midlands would follow a different alignment from that of the existing WCML, because it was considered to be too costly to provide extra capacity by building new rail alongside the existing WCML while the existing track was in use. Furthermore, parts of the existing Victorian-era WCML alignment were not suitable for very high speeds.[n 37]

The Government stated that the new line would improve rail services from London to "Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and other destinations in the north of England and Scotland",[n 38] and an approach route west of London would allow opportunities to "improve surface access by rail to Heathrow Airport."[n 39] Furthermore, if the new line were connected to the Great Western Main Line (GWML) and Crossrail it would provide links with East and West London, and the Thames Valley.[n 40]

Despite a recently completed upgrade, and the expected implementation of plans for longer trains and cab signalling,[n 41] the DfT expected the West Coast Main Line (WCML) - the principal existing railway linking London, the West Midlands, and the North West - to be "overloaded south of Rugby by about 2025".[n 42] This meant the DfT was predicting strong growth, since its report showed the WCML Rugby - Euston section as operating at only 61% and 80% of capacity in the 2008/2009 morning peak[62] with Rugby - Birmingham being in the 41-60% band. The Great Western Chiltern route between Birmingham and London was also shown as being used as 41 to 60% of capacity, with the Leamington - Aynho section being in the 'below 41%' category.[62] The same document's forecast for 2024-2025 was for continued unused capacity on the Great Western Chiltern route.[63]

Accurately forecasting transport demand to 2026 presents sizeable problems, with predictions over much shorter periods proving incorrect. For example, optimistic projections for the East Coast Main Line led National Express to default on its 2007-2015 East Coast franchise in 2009,[64][65] and British Rail, SNCF, London and Continental Railways, and Booz Allen Hamilton overestimated demand for high-speed rail between London, Paris, and Brussels.[66] A large study of transport projects found that, in nine out of ten rail schemes, passenger forecasts were overestimated, with the mean overestimation being 106%.[67]

The DfT asserted that no further WCML significant capacity enhancements were possible without "major disruption to passengers and freight services".[n 37] It was proposed that released capacity on the existing WCML due to construction of HS2 would then be used to enhance services for the Northampton, Milton Keynes and South Midlands area, identified as the "largest growth area in the UK" with a population of 1.6 million people.[n 43]

Notes

- ^ DfT (2010a), page 127

- ^ Atkins(2009)

- ^ DfT (2009a) page 4 paragraph 5

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 5 paragraph 8

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 5 paragraph 9.

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 12 paragraph 37.

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 17 paragraph 40.

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 24 paragraph 63

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 24 paragraph 65.

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 16 paragraph 37

- ^ DfT (2010a), page 9

- ^ DfT (2010a), p. 67 F4.2

- ^ DfT (2010a), page 107

- ^ DfT(2010a), page 118.

- ^ DfT(2010a), page 112

- ^ Department for Transport (2010a), page 115

- ^ DfT(2010a), page 127, section 8.4

- ^ DfT(2010a), page 127

- ^ DfT(2010a), page 129

- ^ DfT(2010a), page 130

- ^ DfT(2010a), page 129

- ^ HS2(2010a), para 4.1.23

- ^ HS2(2010a), Chapter 5.2

- ^ HS2(2010a), p213

- ^ HS2(2010a), p214

- ^ HS2(2010a), p213

- ^ DfT(2010a), page 140

- ^ DfT(2010a), page 138-9

- ^ High Speed 2(2010), page 118

- ^ Booz Allen Hamilton (2007)

- ^ Booz Allen Hamilton (2007), p.6

- ^ DfT(2010a), page 53

- ^ DfT (2009a), pages 12-16 paragraphs 32-37

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 12 paragraph 31

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 18 paragraph 48

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 18 paragraph 47

- ^ a b DfT (2009a), page 12 paragraph 36

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 5 paragraph 4

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 17 paragraph 41

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 18 paragraph 43

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 12 paragraph 43

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 5 paragraph 6

- ^ DfT (2009a), page 12 paragraph 38

References

- Documents referenced from 'Notes' section

- Booz Allen Hamilton (2007). "Estimated Carbon Impact of a New North South Line" (PDF). Department for Transport.

- Atkins (2009). "High Speed Line Study: Summary Report" (PDF). Department for Transport. Retrieved 2010-03-13. [dead link]

- DfT(2009a): Department for Transport (2009). Britain’s Transport Infrastructure High Speed Two (pdf). Department for Transport. ISBN 9781906581800. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- DfT(2010a): Department for Transport (11 March 2010). High Speed Rail - Command Paper (pdf). The Stationery Of?ce. ISBN 9780101782722. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|publisherlink=ignored (help) - HS2(2010a): High Speed Two Ltd (11 March 2010). "High Speed Rail London to the West Midlands and Beyond: A Report to Government by High Speed Two Limited". Department for Transport. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- Other references for article

- ^ Millward, David (4 November 2010). "Country campaigners call for high speed rail rethink". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ "Cheap fast trains 'are transport future' - Lord Adonis". BBC News Online. London. 30 December 2009.

- ^ "The Coalition: our programme for government" (PDF). HM Government. May 2010. p. 31.

- ^ "The case for new lines" (PDF). Meeting the capacity challenge. Network Rail New Lines.

- ^ "High-speed rail plans to be submitted to government". BBC News Online. 27 December 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-28.

- ^ "High-speed rail plans announced by government". BBC News Online. 11 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ "High Speed Rail". Department for Transport. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ^ "Tories would scrap Heathrow plan". BBC News Online. London. 29 September 2008.

- ^ "Where we Stand: Transport", Conservative Party website.

- ^ "Tories say high-speed rail plans for Birmingham are flawed". Birmingham Post. 11 March 2010.

- ^ "Ministers order re-think of high-speed rail route", TransportXtra.com, London, 28 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d Harris, Nigel (28 July 2010). "'No business case' to divert HS2 via Heathrow, says Mawhinney'". RAIL. No. 649. Peterborough. pp. 6–7.

- ^ "A surprising conversion". 30 December 2008.

- ^ "Transport secretary unveils HS2 compensation plan". Railnews. Stevenage. 29 November 2010.

- ^ "High Speed Rail London to the West Midlands and Beyond, Supplementary Report, September 2010: Refining the Alignment of HS2's Recommended Route" (PDF). Department for Transport.

- ^ http://www.conservatives.com/~/media/files/downloadable%20files/railreview.ashx

- ^ "Proposed high speed rail network North of Birmingham confirmed" (Press release). Department for Transport. 4 October 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ Savage, Michael (2 February 2010). "Adonis in all-party talks on high-speed rail link". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ Pank, Philip (30 December 2009). "Britain in line for Europe's fastest railway". The Times. London. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ^ Arup. "Route Engineering Study Final Report: A Report for HS2, chapter 9" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ^ "High Speed Rail: London to the West Midlands and Beyond. A Report to Government by High Speed Two Limited. Chapter 3, p. 134" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ^ "High Speed Rail: London to the West Midlands and Beyond. A Report to Government by High Speed Two Limited. Chapter 3 p. 147" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ^ "High Speed Rail: London to the West Midlands and Beyond. A Report to Government by High Speed Two Limited. Chapter 6 p. 226" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ^ "Virgin Trains timetable" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ^ a b Nielsen, Beverley (29 October 2010). "Up, Up and Away - Birmingham Airport spreads its wings as powerful driver of growth and jobs". Birmingham Post Business Blog.

- ^ "Improved public transport along upgraded A45 will boost jobs and investment" (Press release). Centro. 10 December 2010.

- ^ Dale, Paul (6 April 2010). "Obstacles pile up for Birmingham Airport runway extension". Birmingham Post.

- ^ "High Speed Rail: London to the West Midlands and Beyond. A Report to Government by High Speed Two Limited. Chapter 3 p117" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ^ Walker, Jonathan (16 March 2010). "Birmingham City University wants £30m refund after high speed rail hits campus plan". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ^ Bell, David (29 March 1999). "Tunnel plans halt Bull Ring". Birmingham Post.

- ^ Li, Simon. "Day 972: Bull Ring Tunnel". Flickr.

- ^ a b "New 'parkway' station could be built in East Midlands". Nottingham Evening Post. 3 December 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "High Speed Rail: London to the West Midlands and Beyond. A Report to Government by High Speed Two Limited. Chapter 2 p41" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ^ a b c d "Updated Green Party proposals on HS2 route". Green Party. 22 March 2010.

- ^ "NPF2 Action Programme – Action 3: Develop High Speed Rail Link to London". The Scottish Government. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ^ HS2 action groups (and other HS2 active organisations)HS2 Action Alliance website Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ^ "Council to 'robustly resist' high speed rail". Uxbridge Gazette. 6 December 2010.

- ^ Carswell, Andy (3 December 2010). "High Speed 2 line "will go through Chiltern AONB"". Bucks Free Press. High Wycombe.

- ^ http://www.warwickshire-wildlife-trust.org.uk/media/57738/hs2%20twt%20position%20statement%20oct%202010%20final.pdf

- ^ a b HS2 Action Alliance Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ^ http://www.foe.co.uk/resource/briefings/high_speed_rail.pdf

- ^ "Briefing on White Paper on High Speed Rail, White Paper Response". Campaign for Better Transport.

- ^ "Is High Speed 2 on the Wrong Track?" (Press release). Campaign to Protect Rural England. 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Staffordshire high-speed rail stop 'vital for firms'". BBC News Online. 28 November 2010.

- ^ "Rail campaigners step up fight". Lichfield Mercury. 25 November 2010.

- ^ "Business call for high speed rail cash to be spent on roads". Birmingham Post. 3 December 2010.

- ^ "HS2 route will only benefit Birmingham, says Coventry business boss". Coventry Evening Telegraph. 24 November 2010.

- ^ Walker, Peter (11 March 2010). "Beauty of Chilterns may be put at risk by fast rail link, say critics". The Guardian. London.

- ^ a b "Appraisal of Sustainability: A Report for HS2 Non Technical Summary" (PDF). Department for Transport. December 2009.

- ^ Walker, Jonathan (16 March 2010). "Birmingham City University wants £30m refund after high speed rail hits campus plan". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ^ "Column 31WH—continued". Hansard (House of Commons). 8 December 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "High Speed 2". Chilterns Conservation Board.

- ^ "West Midlands Map 4" (PDF). High Speed 2. Department for Transport. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ "Park Hall". Wildlife Trust for Birmingham and the Black Country. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ^ "The Eddington Transport Study, The case for action: Sir Rod Eddington's advice to Government" (PDF). p. 33.

- ^ "Delivering a sustainable railway". Department for Transport. July 2007: 62.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Concerns arising from the Geology and Hydrology of the ground underlying the High Speed (HS2) routes through the Chilterns". The Chiltern Society.

- ^ "HS2 Exceptional Hardship Scheme consultation document" (PDF). Department for Transport.

- ^ "Alison Munro spoke at a public meeting hosted by Civic Voice in Aylesbury on 24 June".

- ^ "Philip Hammond – Secretary of State for Transport response to questions regarding property blight". Hansard (House of Commons). 28 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|column=ignored (help) - ^ "Alternative Compensation Solution and final response to EHS". HS2 Action Alliance.

- ^ a b "Figure 5: Loading levels in the 3-hour morning peak period, 2008/09" (PDF): 14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Figure 6: Loading levels in the 3-hour morning peak period, 2024/25" (PDF): 15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Osborne, Alistair (4 July 2009). "National Express's decision to quit East Coast franchise is a lose-lose for nearly everyone". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ "East Coast rail to be state-run". BBC News Online. 1 July 2009.

- ^ "Select Committee on Public Accounts Thirty-Eighth Report". www.parliament.gov.uk.

- ^ Flyvbjerg, Bent; Skamris Holm, Mette K.; Buhl, Søren L. (Spring 2005). "How (In)accurate Are Demand Forecasts in Public Works Projects?" (PDF). 71 (2). Chicago: Journal of the American Planning Association: 131 ff.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

- "High Speed Two (HS2) Ltd". www.hs2.org.uk. High Speed Two Ltd.

- High Speed Two Ltd (11 March 2010). "High Speed Rail London to the West Midlands and Beyond: A Report to Government by High Speed Two Limited". www.dft.gov.uk. Department for Transport.

- John Preston (October 2009). "The Case for High Speed Rail:- A review of recent evidence" (PDF). RAC Foundation.

- "High speed rail: In your back yard?". news.bbc.co.uk. BBC News.

Details have been announced of the preferred route for a high-speed rail link between Birmingham and London

- "High Speed Rail". www.dft.gov.uk. Department for Transport.

This section contains information on proposals for high speed rail and the work of the company High Speed Two Ltd

- "High Speed 2 - Caring for the Chilterns , The Chilterns AONB". www.chilternsaonb.org. The Chilterns Conservation Board.