Ayahuasca

- This entry focuses on the Ayahuasca brew; for information on the vine of the same name, see Banisteriopsis caapi

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (September 2010) |

Ayahuasca (ayawaska pronounced [ajaˈwaska] in the Quechua language) is any of various psychoactive infusions or decoctions prepared from the Banisteriopsis spp. vine, usually mixed with the leaves of dimethyltryptamine-containing species of shrubs from the Psychotria genus. The brew, first described academically in the early 1950s by Harvard ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes, who found it employed for divinatory and healing purposes by Amerindians of Amazonian Colombia, is known by a number of different names (see below). A notable and puzzling property of ayahuasca is that neither of the ingredients cause any significant psychedelic effects when imbibed alone; they must be consumed together in order to have the desired effect. How indigenous peoples discovered the psychedelic properties of the ayahuasca brew remains a point of contention in the scientific community.[1]

Preparation

Sections of Banisteriopsis caapi vine are macerated and boiled alone or with leaves from any of a number of other plants, including Psychotria viridis (chacruna) or Diplopterys cabrerana (also known as chaliponga). The resulting brew contains the powerful hallucinogenic alkaloid N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), and MAO inhibiting harmala alkaloids, which are necessary to make the DMT orally active.

Brews can also be made with no DMT-containing plants; Psychotria viridis being substituted by plants such as Justicia pectoralis, Brugmansia, or sacred tobacco, also known as Mapacho (Nicotiana rustica), or sometimes left out with no replacement. The potency of this brew varies radically from one batch to the next, both in potency and psychoactive effect, based mainly on the skill of the shaman or brewer, as well as other admixtures sometimes added and the intent of the ceremony.[citation needed] Natural variations in plant alkaloid content and profiles also affect the final concentration of alkaloids in the brew, and the physical act of cooking may also serve to modify the alkaloid profile of harmala alkaloids.[2][3]

Names

- "cipó" (generic vine, liana), "caapi", "hoasca", "vegetal", "daime" or "santo daime" in Brazil

- "yagé" or "yajé" (both pronounced [jaˈhe]) in Tucanoan; popularized in English by the beat generation writers William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg in The Yage Letters.

- "ayahuasca" or "ayawaska" ("Spirit vine" or "vine of the souls": in Quechua, aya means "spirit" while huasca or waska means "vine") in Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru, and to a lesser extent in Brazil. The spelling ayahuasca is the hispanicized version of the name; many Quechua or Aymara speakers would prefer the spelling ayawaska. The name is properly that of the plant B. caapi, one of the primary sources of beta-carbolines for the brew.

- "natem" amongst the indigenous Shuar and Achuar people of Peru and Ecuador.

- "Grandmother"[where?]

- "Shori"[where?]

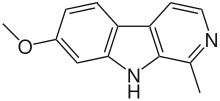

Chemistry

Harmine compounds are of beta-carboline origin. The three most studied beta-carboline compounds found in the B. caapi vine are harmine, harmaline and tetrahydroharmine. Harmine and harmaline are selective and reversible inhibitors of MAO-A, while tetrahydroharmine is a weak serotonin uptake inhibitor. This inhibition of MAO-A allows DMT to diffuse unmetabolized past the membranes in the stomach and small intestine and eventually get through the blood-brain barrier to activate receptor sites in the brain. Without RIMAs or the MAOI of MAO-A, DMT would be metabolized in the digestive tract and would not have an effect when taken orally.[4]

Individual polymorphisms in the cytochrome P450-2D6 enzyme affect the ability of individuals to metabolize harmine.[5] Some natural tolerance to habitual use of ayahuasca (roughly once weekly) may develop through upregulation of the serotonergic system.[6][7] A phase 1 pharmacokinetic study on Ayahuasca (as Hoasca) with 15 volunteers was conducted in 1993, during the Hoasca Project.[6] A review of the Hoasca Project has been published.[8]

Usage

Ayahuasca is used largely as a religious sacrament. Those whose usage of ayahuasca is performed in non-traditional contexts often align themselves with the philosophies and cosmologies associated with ayahuasca shamanism, as practiced among indigenous peoples like the Urarina of Peruvian Amazonia.[9] The religion Santo Daime uses it.

While non-native users know of the spiritual applications of ayahuasca, a less well-known traditional usage[specify] focuses on the medicinal properties of ayahuasca. Its purgative properties are highly important (many refer to it as la purga, "the purge"). The intense vomiting and occasional diarrhea it induces can clear the body of worms and other tropical parasites,[10] and harmala alkaloids themselves have been shown to be anthelmintic[11] Thus, this action is twofold; a direct action on the parasites by these harmala alkaloids (particularly harmine in ayahuasca) works to kill the parasites, and parasites are expelled through the increased intestinal motility that is caused by these alkaloids.

Dietary taboos are often associated with the use of Ayahuasca.[12] In the rainforest, these tend towards the purification of one's self - abstaining from spicy and heavily-seasoned foods, excess fat, salt, caffeine, acidic foods (such as citrus) and sex before, after, or both before and after a ceremony. A diet low in foods containing tyramine has been recommended, as the speculative interaction of tyramine and MAOIs could lead to a hypertensive crisis. However, evidence indicates that harmala alkaloids act only on MAO-A, in a reversible way similar to moclobemide (an antidepressant that does not require dietary restrictions). Psychonautic experiments and the absence of dietary restrictions in the highly urban Brazilian ayahuasca church União do Vegetal also suggest that the risk is much lower than perceived, and probably non-existent.[12]

The name 'ayahuasca' specifically refers to a botanical decoctions that contains Banisteriopsis caapi. A synthetic version, known as pharmahuasca is a combination of an appropriate MAOI and typically DMT. In this usage, the DMT is generally considered the main psychoactive active ingredient, while the MAOI merely preserves the psychoactivity of orally ingested DMT, which would otherwise be destroyed in the gut before it could be absorbed in the body. Thus, ayahuasqueros and most others working with the brew maintain that the B. caapi vine is the defining ingredient, and that this beverage is not ayahuasca unless B. caapi is in the brew. The vine is considered to be the "spirit" of ayahuasca, the gatekeeper and guide to the otherworldly realms.

In some areas[specify], it is even said that the chakruna or chaliponga admixtures are added only to make the brew taste sweeter. This is a strong indicator of the often wildly divergent intentions and cultural differences between the native ayahuasca-using cultures and psychedelics enthusiasts in other countries.

In modern Europe and North America, ayahuasca analogues are often prepared using non-traditional plants which contain the same alkaloids. For example, seeds of the Syrian rue plant can be used as a substitute for the ayahuasca vine, and the DMT-rich Mimosa hostilis is used in place of chakruna. Australia has several indigenous plants which are popular among modern ayahuasqueros there, such as various DMT-rich species of Acacia.

In modern Western culture, entheogen users sometimes base concoctions on Ayahuasca. When doing so, most often Rue or B. caapi is used with an alternative form of the DMT molecule, such as psilocin, or a non-DMT based hallucinogen such as mescaline.[citation needed] Nicknames such as Psilohuasca, Mush-rue-asca, or 'Shroom-a-huasca, for mushroom based mixtures, or Pedrohuasca (from the San Pedro Cactus, which contains mescaline) are often given to such brews. The psychedelic experimentalist trappings of such concoctions bear little resemblance to the medicinal use of Ayahuasca in its original cultural context[citation needed], where ayahuasca is usually ingested only by experienced entheogen users who are more familiar with the chemicals and plants being used.

Introduction to Europe and North America

Ayahuasca is mentioned in the writings of some of the earliest missionaries to South America, but it only became commonly known in Europe and North America much later.[specify] The early missionary reports generally claim it as demonic, and great efforts were made by the Roman Catholic Church to stamp it out.[citation needed] When originally researched in the 20th century, the active chemical constituent of B. caapi was called telepathine, but it was found to be identical to a chemical already isolated from Peganum harmala and was given the name harmaline. The original botanical description done was the Harvard ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes.[citation needed] Having read Schultes's paper, Beat writer William Burroughs sought yagé (still referred to as "telepathine") in the early 1950s while traveling through South America in the hopes that it could relieve or cure opiate addiction (see The Yage Letters). Ayahuasca became more widely known when the McKenna brothers published their experience in the Amazon in True Hallucinations. Dennis later studied the pharmacology, botany, and chemistry of ayahuasca and oo-koo-he, which became the subject of his master's thesis.

In Brazil, a number of modern religious movements based on the use of ayahuasca have emerged, the most famous of them being Santo Daime and the União do Vegetal (or UDV), usually in an animistic context that may be shamanistic or, more often (as with Santo Daime and the UDV), integrated with Christianity. Both Santo Daime and União do Vegetal now have members and churches throughout the world. Similarly, the US and Europe have started to see new religious groups develop in relation to increased ayahuasca use.[13] PaDeva, an American Wiccan group, has become the first incorporated legal church which holds the use of ayahuasca central to their beliefs.[citation needed] Some Westerners have teamed up with shamans in the Amazon rainforest regions, forming Ayahuasca healing retreats that claim to be able to cure mental and physical illness and allow communication with the spirit world. Some reports and scientific studies affirm that ritualized use of ayahuasca may improve mental and physical health.[14]

Holland was an early Western context for the spread of ayahuasca use. Supporting a large Brazilian population, Santo Daime members in particular made efforts to spread the philosophy of ritualized ayahuasca use. In the mid-to-late 1990s one group, the Amsterdam-based Friends of the Forest, was formed by Santo Daime members to introduce ayahuasca to Europeans and others with "allergies to Christianity."[citation needed] They did this by introducing "New Age" rituals incorporating basic ritual structure, celebrating with songs in the Daime tradition (Portuguese waltzes), English language songs, ambient music and mantras and kirtan. They existed at least until the Dutch authorities raided a Santo Daime ritual in progress, and other ayahuasca-oriented groups sensed that an obvious public profile was not in their best interest. Amsterdam is also among the few cities in Europe where one can find, in addition to cannabis, psilocybin mushrooms and peyote, ayahuasca vine, chacruna leaves, and plants for ayahuasca analogues in the tradition of Jonathan Ott's so-called "ayahuasca borealis."[citation needed]

Ayahuasca tourism

"Ayahuasca tourist" refers to a tourist wanting a taste of an exotic ritual or who partakes in modified services geared specifically towards non-indigenous persons. Some seek to clear emotional blocks and gain a sense of peace. Other participants include explorers of consciousness, psychologists, writers, medical doctors, journalists, anthropologists, ethnobotanists, philosophers, and spiritual seekers. Ayahuasca tourism is greatest in Peru, and attracts visitors from all over the world, especially from Europe, USA, Australia, and South Africa, but also from other Latin American countries like Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Colombia and Mexico.

Modern descriptions

Wade Davis (author of The Serpent and The Rainbow [non-fiction][15][16]) describes the traditional mixture as tough in his book One River: "The smell and acrid taste was that of the entire jungle ground up and mixed with bile." [p. 194]

Chilean novelist Isabel Allende told The Sunday Telegraph in London that she once took the drug in an attempt to "punch through" writer's block.[17]

Writer Kira Salak describes her personal experiences with ayahuasca in Peru in the March 2006 issue of National Geographic Adventure magazine.[18][19]

Charles Grob, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at UCLA’s School of Medicine directed in 1993 the Hoasca Project, the first in-depth study of the physical and psychological effects of ayahuasca on humans. He and his team went to Brazil, where the plant mixture can be taken legally, to study members of a church, the União do Vegetal (UDV), who use ayahuasca as a sacrament, and compared them to a control group that had never ingested the substance. The studies found that all the ayahuasca-using UDV members had experienced remission without recurrence of their addictions, depression, or anxiety disorders. Unlike most common anti-depressants, which Grob says can create such high levels of serotonin that cells may actually compensate by losing many of their serotonin receptors, the Hoasca Project showed that ayahuasca strongly enhances the body’s ability to absorb the serotonin that’s naturally there [4]. 'Ayahuasca is perhaps a far more sophisticated and effective way to treat depression than SSRIs [antidepressant drugs],' Grob concludes, adding that the use of SSRIs is 'a rather crude way' of doing it. And ayahuasca, he insists, has great potential as a long-term solution in maintaining abstinence. Here is an excerpt from the article about Dr. Charles Grob's landmark findings[20]: The taking of ayahuasca has been associated with a long list of documented cures: the disappearance of everything from metastasized colorectal cancer to cocaine addiction, even after just a ceremony or two. It has been medically proven to be nonaddictive and safe to ingest. Yet Western scientists have all but ignored it for decades, reluctant to risk their careers by researching a substance containing the outlawed DMT. Only in the past decade, and then only by a handful of researchers, has ayahuasca begun to be studied.

Fred Alan Wolf, a theoretical physicist, writes of his ayahuasca experiences in "The Eagle's Quest: A Physicist's Search for Truth in the Heart of the Shamanic World"

Related phenomena

There have been reports that a phenomenon similar to folie à deux had been induced most recently by anthropologists in the South American rainforest by consuming ayahuasca[20] and by military experiments for chemical warfare in the late 60's using the incapacitating agent BZ. In both incidents there were very rare claims of shared visual hallucinations.

Plant constituents

Traditional

Traditional Ayahuasca brews are always made with Banisteriopsis caapi as a MAOI[citation needed], although DMT sources and other admixtures vary from region to region. There are several varieties of caapi, often known as different "colors", with varying effects, potencies, and uses.

DMT admixtures:

- Psychotria viridis (Chacruna)[21] - leaves

- Diplopterys cabrerana (Chaliponga, Banisteriopsis rusbyana)[21] - leaves

- Psychotria carthagenensis (Amyruca)[21] - leaves

- Acacia maidenii (Maiden's Wattle), Acacia phlebophylla, and other Acacias, most commonly employed in Australia - bark

- Anadenanthera peregrina, A. colubrina, A. excelsa, A. macrocarpa

- Mimosa hostilis (Jurema) - root bark - not traditionally employed with ayahuasca by any existing cultures, though likely it was in the past. Popular in Europe and North America.

MAOI:

- Harmal (Peganum harmala, Syrian Rue) - seeds

- Passion flower

- synthetic MAOIs

Other common admixtures:

- Justicia pectoralis

- Brugmansia (Toé)[21]

- Nicotiana rustica[21] (Mapacho, variety of tobacco)

- Ilex guayusa,[21] a relative of yerba mate

Common admixtures with their associated ceremonial values and spirits:

Dead Head Tree. Provides protection and is used in healing susto (soul loss from spiritual fright or trauma). Head spirit is a headless giant.

Provides cleansing and protection. It is noted for its smooth bark, white flowers, and hard wood. Head spirits look Caucasian.

- Chullachaki Caspi[21] bark

Provides cleansing to the physical body. Used to transcend physical body ailments. Head spirits look Caucasian.

- Lopuna Blanca bark

Provides protection. Head spirits take the form of giants.

- Punga Amarilla bark

Yellow Punga. Provides protection. Used to pull or draw out negative spirits or energies. Head spirit is the yellow anaconda.

- Remo Caspi[21] bark

Oar Tree. Used to move dense or dark energies. Head spirit is a native warrior.

Air Tree. Used to create purging, transcend gastro/intestinal ailments, calm the mind, and bring tranquility. Head spirit looks African.

- Shiwawaku bark

Brings purple medicine to the ceremony. Provides healing and protection.

- Camu camu Gigante:

Head spirit comes in the form of a large dark skinned giant. He provides medicine and protection in the form of warding off dark and demonic spirits.

Head spirit looks like an old Asian warrior with a long white wispy beard. He carries a staff and manages thousands of spirits to protect the ceremony and send away energies that are purged from the participants.

Head of the sanango plants. Provides power, strength, and protection. Head doctor spirit is a grandfather with a long, gray-white beard.

Giant tree of the amazon with very hard bark. Its head spirits come in the form of Amazonian giants and provide a strong grounding presence in the ceremony.

Legal status

Internationally, DMT is a Schedule I drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances. The Commentary on the Convention on Psychotropic Substances notes, however, that the plants containing it are not subject to international control:[22]

The cultivation of plants from which psychotropic substances are obtained is not controlled by the Vienna Convention. . . . Neither the crown (fruit, mescal button) of the Peyote cactus nor the roots of the plant Mimosa hostilis nor Psilocybe mushrooms themselves are included in Schedule 1, but only their respective principles, mescaline, DMT and psilocin.

A fax from the Secretary of the International Narcotics Control Board to the Netherlands Ministry of Public Health sent in 2001 goes on to state that "Consequently, preparations (e.g.decoctions) made of these plants, including ayahuasca, are not under international control and, therefore, not subject to any of the articles of the 1971 Convention."[23]

The legal status in the United States of DMT-containing plants is somewhat questionable. Ayahuasca plants and preparations are legal, as they contain no scheduled chemicals. However, brews made using DMT containing plants are illegal since DMT is a Schedule I drug. That said, some people are challenging this, using arguments similar to those used by peyotist religious sects, such as the Native American Church. A court case allowing União do Vegetal to use the tea for religious purposes in the United States, Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court on November 1, 2005; the decision, released February 21, 2006, allows the UDV to use the tea in its ceremonies pursuant to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. In a similar case an Ashland, Oregon based Santo Daime church sued for their right to import and consume ayahuasca tea. In March 2009, U.S. District Court Judge Panner ruled in favor of the Santo Daime, acknowledging its protection from prosecution under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.[24]

Religious use in Brazil was legalized after two official inquiries into the tea in the mid-1980s, which concluded that ayahuasca is not a recreational drug and has valid spiritual uses.[25]

In France, Santo Daime won a court case allowing them to use the tea in early 2005; however, they were not allowed an exception for religious purposes, but rather for the simple reason that they did not perform chemical extractions to end up with pure DMT and harmala and the plants used were not scheduled.[26] Four months after the court victory, the common ingredients of Ayahuasca as well as harmala were declared stupéfiants, or narcotic schedule I substances, making the tea and its ingredients illegal to use or possess.[27]

This article needs to be updated. (November 2010) |

In Peru, the government is undergoing the legislation process of legalizing and regulating Ayahuasca usage and monitoring Ayahuasca centers. Currently (April 2010) the use of Ayahuasca is not technically legal but since it is an accepted practice of its indigenous cultures the Peruvian government is going through of the process maintaining the continuity of its culture whilst avoiding international issues.

International research

The Institute of Medical Psychology at the University Hospital in Heidelberg, Germany has set up a Research Department Ayahuasca / Santo Daime,[28] which in May 2008 held a 3-day conference under the title The globalization of Ayahuasca - An Amazonian psychoactive and its users.[29] There are also the investigations of the human pharmacology of ayahuasca done by the team of Doctor Jordi Riba, in Barcelona, Spain [4][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38] and the work of Rafael G. dos Santos and collaborators, in Brazil,[39][40][41][42][43][44] And there are also the studies (i.e. Hoasca Project and others) by Dr. Charles Grob and collaborators (e.g., Dr. Callaway and Dr. McKenna), already cited, done in Brazil, United States and Finland. In Brazil, the University of São Paulo is doing a study led by psychiatrist Dartiu Xavier da Silveira to establish the risks of ayahuasca.[citation needed]

See also

References

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2011) |

Bibliography

Nonfiction

- Adelaars, Arno. Ayahuasca. Rituale, Zaubertränke und visionäre Kunst aus Amazonien, ISBN 978-3-03800-270-3

- Bartholomew, Dean 2009 Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia, Gainesville: University Press of Florida ISBN 978-081303378 [1]

- Burroughs, William S. and Allen Ginsberg. The Yage Letters. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1963. ISBN 0-87286-004-3

- Marlene Dobkin De Rios. Visionary Vine: Hallucinogenic Healing in the Peruvian Amazon, (2nd ed.). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland, 1984. ISBN 0-88133-093-0

- Marlene Dobkin de Rios & Roger Rumrrill. A Hallucinogenic Tea, Laced with Controversy: Ayahuasca in the Amazon and the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2008. ISBN 97-0-313-34542-5

- Sylvia Fraser, "The Green Labyrinth: Exploring the Mysteries of the Amazon". Toronto: Thomas Allen, 2003. ISBN 0-88762-123-6.

- Graham Hancock, Supernatural: Meetings with the Ancient Teachers of Mankind. London: Century, 2005. ISBN 1844136817 [2]

- Ross Heaven and Howard G. Charing. 'Plant Spirit Shamanism: Traditional Techniques for Healing the Soul'. Vermont: Destiny Books, 2006. ISBN 1-59477-118-9

- Bruce F. Lamb. Rio Tigre and Beyond: The Amazon Jungle Medicine of Manuel Córdova. Berkeley: North Atlantic, 1985. ISBN 0-938190-59-8

- E. Jean Matteson Langdon & Gerhard Baer, eds. Portals of Power: Shamanism in South America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8263-1345-0

- Luis Eduardo Luna. Vegetalismo: Shamanism among the Mestizo Population of the Peruvian Amazon. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International, 1986. ISBN 91-22-00819-5

- Luis Eduardo Luna & Pablo Amaringo. Ayahuasca Visions: The Religious Iconography of A Peruvian Shaman. Berkeley: North Atlantic, 1999. ISBN 1-55643-311-5

- Luis Eduardo Luna & Stephen F. White, eds. Ayahuasca Reader: Encounters with the Amazon's Sacred Vine. Santa Fe, NM: Synergetic, 2000. ISBN 0-907791-32-8

- Terence McKenna. Food of the Gods: A Radical History of Plants, Drugs, and Human Evolution.

- Ralph Metzner, ed. Ayahuasca: Hallucinogens, Consciousness, and the Spirit of Nature. New York: Thunder's Mouth, 1999. ISBN 1-56025-160-3

- Ralph Metzner (Editor) Sacred Vine of Spirits: Ayahuasca: Park Street Press,U.S.; 2 edition (Jan 2006). ISBN 1594770530, ISBN 978-1594770531

- Jeremy Narby. The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1998. ISBN 0-87477-911-1

- P. J. O'Rourke, All the Trouble in the World. New York: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1994. ISBN 0-87113-611-2

- Jonathan Ott. Ayahuasca Analogues: Pangæan Entheogens. Kennewick, Wash.: Natural Products, 1994. ISBN 0-9614234-5-5

- Jonathan Ott. Pharmacotheon: Entheogenic Drugs, Their Plant Sources and History (Paperback). Natural Products Company; 2 edition (February 1993). ISBN 0961423498. ISBN 978-0961423490

- Ott, J. 1999. Pharmahuasca: Human pharmacology of oral DMT plus harmine, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 31(2): I7I-177.

- John Perkins. The World Is As You Dream It: Shamanic Teachings from the Amazon and Andes. Rochester, Vt.: Park Street, 1994. ISBN 0-89281-459-4 [3]

- Daniel Pinchbeck. Breaking Open the Head: A Psychedelic Journey into the Heart of Contemporary Shamanism. New York: Broadway, 2002. ISBN 0-7679-0743-4 [4]

- Alex Polari de Alverga. Forest of Visions: Ayahuasca, Amazonian Spirituality, and the Santo Daime Tradition. Rochester, Vt.: Park Street, 1999. ISBN 0-89281-716-X

- Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff. The Shaman and the Jaguar: A Study of Narcotic Drugs Among the Indians of Colombia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1975. ISBN 0-87722-038-7

- Richard Evans Schultes & Robert F. Raffauf. Vine of the Soul: Medicine Men, Their Plants and Rituals in the Colombian Amazonia. Oracle, AZ: Synergetic, 1992. ISBN 0-907791-24-7

- Benny Shanon. The Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-925293-9

- Peter G. Stafford. Heavenly Highs: Ayahuasca, Kava-Kava, Dmt, and Other Plants of the Gods. Berkeley: Ronin, 2004. ISBN 1-57951-069-8

- Rick Strassman. DMT: The Spirit Molecule: A Doctor's Revolutionary Research into the Biology of Near-Death and Mystical Experiences. Rochester, Vt.: Park Street, 2001. ISBN 0-89281-927-8

- Sting. Broken Music. New York, NY: Bantam Dell, 2003. ISBN 978-0-440-24115-7

- Michael Taussig. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986. ISBN 0-226-79012-6

- Joan Parisi Wilcox (2003). Ayahuasca: The Visionary and Healing Powers of the Vine of the Soul. Rochester, Vt.: Park Street. ISBN 0-89281-131-5

- Rätsch, Christian (2005). The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants. Park Street Press. ISBN 978-0892819782

Documentaries

- Alistair Appleton, The Man Who Drank the Universe, 30 min. 2005

- Dean Jefferys; Shamans of the Amazon, 52 min. Australia 2001

- Jan Kounen, Autres mondes

- Glenn Switkes, Night of the Liana, 45 min. Brazil 2002

- Armand BERNARDI, L'Ayahuasca, le Serpent et Moi, 52 min. France 2003

- Anna Stevens, Woven Songs of the Amazon, 54 min. 2006

- Rudolf Pinto do Amaral & Harald Scherz, ["Heaven Earth"], 60 min. Peru/Austria 2008

- Keith Aronowitz "METAMORPHOSIS" 95 min. / 2009 Official website

- Madventures Season 3 Episode 1: Riku & Tunna venture deep into the Amazon to find themselves and drink ayahuasca with a shaman.

- Piers Gibbon, Jungle Trip - Channel 4 UK from Google Video

- Richard Meech, Vine of the Soul: Encounters with Ayahuasca, 58 min. Canada 2010

- BBC - Bruce Parry's Amazon, Peru, 2008, Episode 2

- The Spirit Molecule

Notes

- ^ "Ayahuasca.com - Overviews Shamanism - On The Origin of Ayahuasca". Retrieved August, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Callaway JC (2005). "Various alkaloid profiles in decoctions of Banisteriopsis caapi". J Psychoactive Drugs. 37 (2): 151–5. PMID 16149328.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Callaway JC, Brito GS, Neves ES (2005). "Phytochemical analyses of Banisteriopsis caapi and Psychotria viridis". J Psychoactive Drugs. 37 (2): 145–50. PMID 16149327.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b RIBA, J. Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca. Doctoral Thesis: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2003.

- ^ Callaway JC (2005). "Fast and slow metabolizers of Hoasca". J Psychoactive Drugs. 37 (2): 157–61. PMID 16149329.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Callaway JC, McKenna DJ, Grob CS, Brito GS, Raymon LP, Poland RE, Andrade EN, Andrade EO (1999). "Pharmacokinetics of Hoasca alkaloids in healthy humans". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 65 (3): 243–256. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(98)00168-8. PMID 10404423.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Callaway JC, Airaksinen MM, McKenna DJ, Brito GS, Grob CS (1994). "Platelet serotonin uptake sites increased in drinkers of ayahuasca". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 116 (3): 385–7. doi:10.1007/BF02245347. PMID 7892432.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McKenna DJ, Callaway JC, Grob CS (1998). "The scientific investigation of ayahuasca: A review of past and current research". The Heffter Review of Psychedelic Research. 1: 65–77.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dean, Bartholomew (2009). Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-3378-5.

- ^ Andritzky W (1989). "Sociopsychotherapeutic functions of ayahuasca healing in Amazonia". J Psychoactive Drugs. 21 (1): 77–89. PMID 2656954.

- ^ Hassan, I. (1967). "Some folk uses of Peganum harmala in India and Pakistan". Economic Botany. 21 (3): 384. doi:10.1007/BF02860378.

- ^ a b Ott, J. (1994). Ayahuasca Analogues: Pangaean Entheogens. Kennewick, WA: Natural Books. ISBN 978-0961423445.

- ^ Labate, B.C.; Rose, I.S. & Santos, R.G. (2009). Ayahuasca Religions: a comprehensive bibliography and critical essays. Santa Cruz: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies - MAPS. ISBN 978-0979862212.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ See research by Doctor John Halpern in New Scientist

- ^ There is a 1988 American horror film, directed by Wes Craven and starring Bill Pullman. The film is very loosely based on a non-fiction book by ethnobotanist Wade Davis. Statement by Mr. Davis: ''Davis has frequently voiced his displeasure with the final film. "When I wrote my first book, 'The Serpent and the Rainbow', it was made into one of the worst Hollywood movies in history. I tried to escape the hysteria and the media by going to Borneo."

- ^ http://www.ed.psu.edu/icik/2004Proceedings/section7-davis.pdf

- ^ Elsworth, Catherine (2008-03-21). "Isabel Allende: kith and tell". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ Salak, Kira. "Hell And Back". Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ Salak, Kira. "Ayahuasca Healing in Peru". Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ Ayahuasca: Human Consciousness and the Spirits of Nature, edited by Ralph Metzner, Thunder's Mouth Press, NY

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ratsch 2005, pp. 704–708

- ^ MAPS: DMT - UN report

- ^ Erowid Ayahuasca Vault : Law : UNDCP's Ayahuasca Fax, Jan 17 2001

- ^ Ruling by District Court Judge Panner in Santo Daime case in Oregon

- ^ More on the legal status of ayahuasca can be found in the Erowid vault on the legality of ayahuasca.

- ^ Cour d'appel de Paris, 10ème chambre, section B, dossier n° 04/01888. Arrêt du 13 janvier 2005 [Court of Appeal of Paris, 10th Chamber, Section B, File No. 04/01888. Judgement of 13 January 2005]. PDF of this document may be obtained from Ayahuasca - Santo Daime Library.

- ^ JO, 2005-05-03. Arrêté du 20 avril 2005 modifiant l'arrêté du 22 février 1990 fixant la liste des substances classées comme stupéfiants (PDF) [Decree of 20 April 2005 amending the decree of 22 February 1990 establishing the list of substances scheduled as narcotics].

- ^ 'Research Department Ayahuasca / Santo Daime' at the University Hospital in Heidelberg, Germany

- ^ Conference schedule "The globalization of Ayahuasca" (May 2008, Heidelberg, Germany)

- ^ Riba J, Barbanoj MJ (2005). "Bringing ayahuasca to the clinical research laboratory". J Psychoactive Drugs. 37 (2): 219–30. PMID 16149336.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Riba, J. & Barbanoj, M.J. Ayahuasca (2006). Peris, J.C., Zurián, J.C., Martínez, G.C. & Valladolid, G.R. (ed.). "Tratado SET de Transtornos Adictivos". Madrid: Ed. Médica Panamericana: 321–324. ISBN 9788479031640.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riba J, Rodríguez-Fornells A, Strassman RJ, Barbanoj MJ (2001). "Psychometric assessment of the Hallucinogen Rating Scale". Drug Alcohol Depend. 62 (3): 215–23. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00175-7. PMID 11295326.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riba J, Rodríguez-Fornells A, Urbano G; et al. (2001). "Subjective effects and tolerability of the South American psychoactive beverage Ayahuasca in healthy volunteers". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 154 (1): 85–95. doi:10.1007/s002130000606. PMID 11292011.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riba J, Anderer P, Morte A; et al. (2002). "Topographic pharmaco-EEG mapping of the effects of the South American psychoactive beverage ayahuasca in healthy volunteers". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 53 (6): 613–28. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01609.x. PMC 1874340. PMID 12047486.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riba, J., Rodriguez–Fornells, A., & Barbanoj, M.j. (2002). "Effects of ayahuasca sensory and sensorimotor gating in humans as measured by P50 suppression and prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex, respectively". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 165 (1): 18–28. doi:10.1007/s00213-002-1237-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riba J, Valle M, Urbano G, Yritia M, Morte A, Barbanoj MJ (2003). "Human pharmacology of ayahuasca: subjective and cardiovascular effects, monoamine metabolite excretion, and pharmacokinetics". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 306 (1): 73–83. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.049882. PMID 12660312.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riba J, Anderer P, Jané F, Saletu B, Barbanoj MJ (2004). "Effects of the South American psychoactive beverage ayahuasca on regional brain electrical activity in humans: a functional neuroimaging study using low-resolution electromagnetic tomography". Neuropsychobiology. 50 (1): 89–101. doi:10.1159/000077946. PMID 15179026.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riba J, Romero S, Grasa E, Mena E, Carrió I, Barbanoj MJ (2006). "Increased frontal and paralimbic activation following ayahuasca, the pan-Amazonian inebriant". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 186 (1): 93–8. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0358-7. PMID 16575552.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Santos, R.G., Moraes, C.C. & Holanda, A. (2006). "Ayahuasca e redução do uso abusivo de psicoativos: eficácia terapêutica?". Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa. 22 (3): 363–370. doi:10.1590/S0102-37722006000300014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ SANTOS, R.G. (2007). "AYAHUASCA: Neuroquímica e Farmacologia". SMAD - Revista Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool e Drogas. 3 (1).

- ^ Santos RG, Landeira-Fernandez J, Strassman RJ, Motta V, Cruz AP (2007). "Effects of ayahuasca on psychometric measures of anxiety, panic-like and hopelessness in Santo Daime members" (PDF). J Ethnopharmacol. 112 (3): 507–13. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.04.012. PMID 17532158.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Santos, R.G. & Strassman, R.J. (3 December 2008). "Ayahuasca and Psychosis (eLetter)". British Journal of Psychiatry.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ SANTOS, R.G. (2010). "The pharmacology of ayahuasca: a review" (PDF). Brasília Médica. 47 (2): 188–195.

- ^ SANTOS, R.G. (2010). "Toxicity of chronic ayahuasca administration to the pregnant rat: how relevant it is regarding the human, ritual use of ayahuasca?" (PDF). Birth Defects Research Part B: Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology. 89 (6): 533–535. doi:10.1002/bdrb.20272.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (July 2010) |

- Overview

- The Ayahuasca Foundation - A non-profit organization that preserves ayahuasca culture

- Ayahuasca.com - Research project devoted to ayahuasca

- Ayahuasca - Pharmacology and personal experiences from lycaeum.org

- Ethnobotany and Bioactivity of Ayahuasca by M. Goldberg, E. Mosquera, R. Arawanza, and E. Rodriguez

- National Geographic article on ayahuasca

- The Sacred Vine

- Legal

- Other

- Ayahuasca and other "plant teachers"—educational potential?

- Ayahuasca Healing Beyond the Amazon: The Globalization of a Traditional Indigenous Entheogenic Practice Global Networks: A Journal of Transnational Affairs, vol. 9, no. 1, 2009

- The Globalization of Ayahuasca: Harm Reduction or Benefit Maximization? International Journal of Drug Policy, vol. 19, no. 4, 2008