Anarchism

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

Anarchism is a political philosophy which considers the state undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, and instead promotes a stateless society, or anarchy.[1][2] It seeks to diminish or even abolish authority in the conduct of human relations.[3] Anarchists widely disagree on what additional criteria are required in anarchism. The Oxford Companion to Philosophy says, "there is no single defining position that all anarchists hold, and those considered anarchists at best share a certain family resemblance."[4]

There are many types and traditions of anarchism, some of which are mutually exclusive.[5] Strains of anarchism have been divided into the categories of social and individualist anarchism or similar dual classifications.[6][7] Anarchism is often considered to be a radical left-wing ideology,[8][9] and much of anarchist economics and anarchist legal philosophy reflect anti-statist interpretations of communism, collectivism, syndicalism or participatory economics. However, anarchism has always included an individualist strain [10] supporting a market economy and private property, or morally unrestrained egoism.[11][12] Some individualist anarchists are also socialists.[13][14]

Differing fundamentally, some anarchist schools of thought support anything from extreme individualism to complete collectivism.[2] In the end, for anarchist historian Daniel Guerin "Some anarchists are more individualistic than social, some more social than individualistic. However, one cannot conceive of a libertarian who is not an individualist."[15] The position known as anarchism without adjectives insists on "recognising the right of other tendencies to the name 'anarchist' while, obviously, having their own preferences for specific types of anarchist theory and their own arguments why other types are flawed."[16]

The central tendency of anarchism as a mass social movement has been represented by anarcho-communism and anarcho-syndicalism, with individualist anarchism being primarily philosophical.[17] Some anarchists fundamentally oppose all forms of aggression, supporting self-defense or non-violence (anarcho-pacifism),[18][19] while others have supported the use of some coercive measures, including violent revolution and propaganda of the deed, on the path to an anarchist society.[20]

Etymology and terminology

The term anarchism derives from the Greek ἄναρχος, anarchos, meaning "without rulers",[21][22] from the prefix ἀν- (an-, "without") + ἀρχή (archê, "sovereignty, realm, magistracy")[23] + -ισμός (-ismos, from the suffix -ιζειν, -izein "-izing"). There is some ambiguity with the use of the terms "libertarianism" and "libertarian" in writings about anarchism. Since the 1890s from France,[24] the term "libertarianism" has often been used as a synonym for anarchism and was used almost exclusively in this sense until the 1950s in the United States;[25] its use as a synonym is still common outside the United States.[26] Accordingly, "libertarian socialism" is sometimes used as a synonym for socialist anarchism,[27][28] to distinguish it from "individualist libertarianism" (individualist anarchism). On the other hand, some use "libertarianism" to refer to individualistic free-market philosophy only, referring to free-market anarchism as "libertarian anarchism".[29][30]

Origins

Anarchist themes can be found in the works of Taoist sages Laozi[31], Zhuangzi and Bao Jingyan [9]. Zhuangzi wrote, "A petty thief is put in jail. A great brigand becomes a ruler of a Nation,"[32] while Bao Jingyan said that as soon as "the relationship between lord and subject is established, hearts become daily filled with evil designs, until the manacled criminals sullenly doing forced labour in the mud and the dust are full of mutinous thoughts." Diogenes of Sinope and the Cynics, their contemporary Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, also introduced similar topics.[31][33]

The term "anarchist" first entered the English language in 1642, during the English Civil War, as a term of abuse, used by Royalists against their Roundhead opponents.[34] By the time of the French Revolution some, such as the Enragés, began to use the term positively,[35] in opposition to Jacobin centralisation of power, seeing "revolutionary government" as oxymoronic.[34] By the turn of the 19th century, the English word "anarchism" had lost its initial negative connotation.[34]

Modern anarchism sprang from the secular or religious thought of the Enlightenment, particularly Jean-Jacques Rousseau's arguments for the moral centrality of freedom.[36] From this climate William Godwin developed what many consider the first expression of modern anarchist thought.[37] Godwin was, according to Peter Kropotkin, "the first to formulate the political and economical conceptions of anarchism, even though he did not give that name to the ideas developed in his work",[31] while Godwin attached his anarchist ideas to an early Edmund Burke.[38] Benjamin Tucker instead credits Josiah Warren, an American who promoted stateless and voluntary communities where all goods and services were private, with being "the first man to expound and formulate the doctrine now known as Anarchism."[39] The first to describe himself as an anarchist was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon,[34] a French philosopher and politician, which led some to call him the founder of modern anarchist theory.[40]

Social movement

Anarchism as a social movement has regularly endured fluctuations in popularity. Its classical period, which scholars demarcate as from 1860 to 1939, is associated with the working-class movements of the 19th century and the Spanish Civil War-era struggles against fascism.[41]

The First International

In Europe, harsh reaction followed the revolutions of 1848, during which ten countries had experienced brief or long-term social upheaval as groups carried out nationalist uprisings. After most of these attempts at systematic change ended in failure, conservative elements took advantage of the divided groups of socialists, anarchists, liberals, and nationalists, to prevent further revolt.[42] In 1864 the International Workingmen's Association (sometimes called the "First International") united diverse revolutionary currents including French followers of Proudhon,[43] Blanquists, Philadelphes, English trade unionists, socialists and social democrats.

Due to its links to active workers' movements, the International became a significant organization. Karl Marx became a leading figure in the International and a member of its General Council. Proudhon's followers, the mutualists, opposed Marx's state socialism, advocating political abstentionism and small property holdings.[44][45]

In 1868, following their unsuccessful participation in the League of Peace and Freedom (LPF), Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin and his collectivist anarchist associates joined the First International (which had decided not to get involved with the LPF).[46] They allied themselves with the federalist socialist sections of the International,[47] who advocated the revolutionary overthrow of the state and the collectivization of property.

At first, the collectivists worked with the Marxists to push the First International in a more revolutionary socialist direction. Subsequently, the International became polarised into two camps, with Marx and Bakunin as their respective figureheads.[48] Bakunin characterised Marx's ideas as centralist and predicted that, if a Marxist party came to power, its leaders would simply take the place of the ruling class they had fought against.[49][50]

In 1872, the conflict climaxed with a final split between the two groups at the Hague Congress, where Bakunin and James Guillaume were expelled from the International and its headquarters were transferred to New York. In response, the federalist sections formed their own International at the St. Imier Congress, adopting a revolutionary anarchist program.[51]

Organised labour

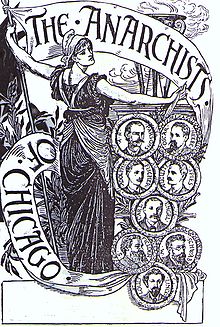

The anti-authoritarian sections of the First International were the precursors of the anarcho-syndicalists, seeking to "replace the privilege and authority of the State" with the "free and spontaneous organization of labor."[52] In 1886, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (FOTLU) of the United States and Canada unanimously set 1 May 1886, as the date by which the eight-hour work day would become standard.[53]

In response, unions across the United States prepared a general strike in support of the event.[53] On 3 May, in Chicago, a fight broke out when strikebreakers attempted to cross the picket line, and two workers died when police opened fire upon the crowd.[54] The next day, 4 May, anarchists staged a rally at Chicago's Haymarket Square.[55] A bomb was thrown by an unknown party near the conclusion of the rally, killing an officer.[56] In the ensuing panic, police opened fire on the crowd and each other.[57] Seven police officers and at least four workers were killed.[58] Eight anarchists directly and indirectly related to the organisers of the rally were arrested and charged with the murder of the deceased officer. The men became international political celebrities among the labour movement. Four of the men were executed and a fifth committed suicide prior to his own execution. The incident became known as the Haymarket affair, and was a setback for the labour movement and the struggle for the eight hour day. In 1890 a second attempt, this time international in scope, to organise for the eight hour day was made.The event also had the secondary purpose of memorializing workers killed as a result of the Haymarket affair.[59] Although it had initially been conceived as a once-off event, by the following year the celebration of International Workers' Day on May Day had become firmly established as an international worker's holiday.[53]

In 1907, the International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam gathered delegates from 14 different countries, among which important figures of the anarchist movement, including Errico Malatesta, Pierre Monatte, Luigi Fabbri, Benoît Broutchoux, Emma Goldman, Rudolf Rocker, and Christiaan Cornelissen. Various themes were treated during the Congress, in particular concerning the organisation of the anarchist movement, popular education issues, the general strike or antimilitarism. A central debate concerned the relation between anarchism and syndicalism (or trade unionism). Malatesta and Monatte were in particular disagreement themselves on this issue, as the latter thought that syndicalism was revolutionary and would create the conditions of a social revolution, while Malatesta did not consider syndicalism by itself sufficient.[60] He thought that the trade-union movement was reformist and even conservative, citing as essentially bourgeois and anti-worker the phenomenon of professional union officials. Malatesta warned that the syndicalists aims were in perpetuating syndicalism itself, whereas anarchists must always have anarchy as their end and consequently refrain from committing to any particular method of achieving it.[61]

The Spanish Workers Federation in 1881 was the first major anarcho-syndicalist movement; anarchist trade union federations were of special importance in Spain. The most successful was the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (National Confederation of Labour: CNT), founded in 1910. Before the 1940s, the CNT was the major force in Spanish working class politics, attracting 1.58 million members at one point and playing a major role in the Spanish Civil War.[62] The CNT was affiliated with the International Workers Association, a federation of anarcho-syndicalist trade unions founded in 1922, with delegates representing two million workers from 15 countries in Europe and Latin America. In Latin America in particular "The anarchists quickly became active in organizing craft and industrial workers throughout South and Central America, and until the early 1920s most of the trade unions in Mexico, Brazil, Peru, Chile, and Argentina were anarcho-syndicalist in general outlook; the prestige of the Spanish C.N.T. as a revolutionary organization was undoubtedly to a great extent responsible for this situation. The largest and most militant of these organizations was the Federación Obrera Regional Argentina...it grew quickly to a membership of nearly a quarter of a million, which dwarfed the rival socialdemocratic unions."[19]

The largest organised anarchist movement today is in Spain, in the form of the Confederación General del Trabajo (CGT) and the CNT. CGT membership was estimated to be around 100,000 for 2003.[63] Other active syndicalist movements include the US Workers Solidarity Alliance and the UK Solidarity Federation. The revolutionary industrial unionist Industrial Workers of the World, claiming 2,000 paying members, and the International Workers Association, an anarcho-syndicalist successor to the First International, also remain active.

Propaganda of the deed and illegalism

Some anarchists, such as Johann Most, advocated publicizing violent acts of retaliation against counter-revolutionaries because "we preach not only action in and for itself, but also action as propaganda."[64] By the 1880s, the slogan "propaganda of the deed" had begun to be used both within and outside of the anarchist movement to refer to individual bombings, regicides and tyrannicides. From 1905 onwards, the Russian counterparts of these anti-syndicalist anarchist-communists become partisans of economic terrorism and illegal ‘expropriations’."[65] Illegalism as a practice emerged and within it "The acts of the anarchist bombers and assassins ("propaganda by the deed") and the anarchist burglars ("individual reappropriation") expressed their desperation and their personal, violent rejection of an intolerable society. Moreover, they were clearly meant to be exemplary , invitations to revolt.".[66] France's Bonnot Gang was the most famous group to embrace illegalism.

However, as soon as 1887, important figures in the anarchist movement distanced themselves from such individual acts. Peter Kropotkin thus wrote that year in Le Révolté that "a structure based on centuries of history cannot be destroyed with a few kilos of dynamite".[67] A variety of anarchists advocated the abandonment of these sorts of tactics in favor of collective revolutionary action, for example through the trade union movement. The anarcho-syndicalist, Fernand Pelloutier, argued in 1895 for renewed anarchist involvement in the labor movement on the basis that anarchism could do very well without "the individual dynamiter."[68]

State repression (including the infamous 1894 French lois scélérates) of the anarchist and labor movements following the few successful bombings and assassinations may have contributed to the abandonment of these kinds of tactics, although reciprocally state repression, in the first place, may have played a role in these isolated acts. The dismemberment of the French socialist movement, into many groups and, following the suppression of the 1871 Paris Commune, the execution and exile of many communards to penal colonies, favored individualist political expression and acts.[69]

Numerous heads of state were assassinated between 1881 and 1914 by members of the anarchist movement. For example, U.S. President McKinley's assassin Leon Czolgosz claimed to have been influenced by anarchist and feminist Emma Goldman. This was in spite of Goldman's disavowal of any association with him, his registered membership in the Republican Party, and never having belonged to an anarchist organization. Bombings were associated in the media with anarchists because international terrorism arose during this time period with the widespread distribution of dynamite. This image remains to this day.

Propaganda of the deed was abandoned by the vast majority of the anarchist movement after World War I (1914–1918) and the 1917 October Revolution.

Russian Revolution

Anarchists participated alongside the Bolsheviks in both February and October revolutions, and were initially enthusiastic about the Bolshevik coup.[70] However, the Bolsheviks soon turned against the anarchists and other left-wing opposition, a conflict that culminated in the 1921 Kronstadt rebellion which the new government repressed. Anarchists in central Russia were either imprisoned, driven underground or joined the victorious Bolsheviks; the anarchists from Petrograd and Moscow fled to the Ukraine.[71] There, in the Free Territory, they fought in the civil war against the Whites (a grouping of monarchists and other opponents of the October Revolution) and then the Bolsheviks as part of the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine led by Nestor Makhno, who established an anarchist society in the region for a number of months.

Expelled American anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman were amongst those agitating in response to Bolshevik policy and the suppression of the Kronstadt uprising, before they left Russia. Both wrote accounts of their experiences in Russia, criticizing the amount of control the Bolsheviks exercised. For them, Bakunin's predictions about the consequences of Marxist rule that the rulers of the new "socialist" Marxist state would become a new elite had proved all too true.[49][72]

The victory of the Bolsheviks in the October Revolution and the resulting Russian Civil War did serious damage to anarchist movements internationally. Many workers and activists saw Bolshevik success as setting an example; Communist parties grew at the expense of anarchism and other socialist movements. In France and the United States, for example, members of the major syndicalist movements of the CGT and IWW left the organizations and joined the Communist International.[73]

In Paris, the Dielo Truda group of Russian anarchist exiles, which included Nestor Makhno, concluded that anarchists needed to develop new forms of organisation in response to the structures of Bolshevism. Their 1926 manifesto, called the Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft),[74] was supported. Platformist groups active today include the Workers Solidarity Movement in Ireland and the North Eastern Federation of Anarchist Communists of North America. Synthesis anarchism emerged as an organizational alternative to platformism which tries to join anarchists of different tendencies under the principles of anarchism without adjectives.[75] In the 1920s this form found as its main proponents Volin and Sebastien Faure.[75] It is the main principle behind the anarchist federations grouped around the contemporary global International of Anarchist Federations.[75]

Fight against fascism and World War II

In the 1920s and 1930s, the rise of fascism in Europe transformed anarchism's conflict with the state. Italy saw the first struggles between anarchists and fascists. Italian anarchists played a key role in the anti-fascist organisation Arditi del Popolo, which was strongest in areas with anarchist traditions, and achieved some success in their activism, such as repelling Blackshirts in the anarchist stronghold of Parma in August 1922.[76] The veteran Italian anarchist, Luigi Fabbri, was one of the first critical theorists of fascism, describing it as "the preventive counter-revolution." [10] In France, where the far right leagues came close to insurrection in the February 1934 riots, anarchists divided over a united front policy.[77]

In Spain, the CNT initially refused to join a popular front electoral alliance, and abstention by CNT supporters led to a right wing election victory. But in 1936, the CNT changed its policy and anarchist votes helped bring the popular front back to power. Months later, the former ruling class responded with an attempted coup causing the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939).[78] In response to the army rebellion, an anarchist-inspired movement of peasants and workers, supported by armed militias, took control of Barcelona and of large areas of rural Spain where they collectivised the land.[79] But even before the fascist victory in 1939, the anarchists were losing ground in a bitter struggle with the Stalinists, who controlled the distribution of military aid to the Republican cause from the Soviet Union. Stalinist-led troops suppressed the collectives and persecuted both dissident Marxists and anarchists.[80]

Anarchists in France[81] and Italy[82] were active in the Resistance during World War II.

Post-war years

Anarchism sought to reorganize itself after the war. In 1939 the Mexican Anarchist Federation is established.[83] In the early 1940s the Antifascist International Solidarity and Federation of Anarchist Groups of Cuba merge into the large national organization Asociación Libertaria de Cuba (Cuban Libertarian Association).[84] From 1944 to 1947, the Bulgarian Anarchist Communist Federation reemerges as part of a factory and workplace committee movement, but is repressed by the new Communist regime.[85] In 1945 in France the Fédération Anarchiste is established and the synthesist Federazione Anarchica Italiana is founded in Italy. Korean anarchists form the League of Free Social Constructors in September 1945[86] and in 1946 the Japanese Anarchist Federation is founded.[87] An International Anarchist Congress with delegates from across Europe is held in Paris in May 1948.[88] In 1956 the Uruguayan Anarchist Federation is founded.[89] In 1955 the Anarcho-Communist Federation of Argentina renames itself as the Argentine Libertarian Federation.

Anarchism continued to be influential in important literary and intellectual personalities of the time such as Albert Camus, Herbert Read, Paul Goodman, Allen Ginsberg, Julian Beck and the French Surrealist group led by André Breton which now openly embraced anarchism and collaborated in the Fédération Anarchiste.[90]

Anarcho-pacifism became influential in the Anti-nuclear movement and anti war movements of the time[91][92] as can be seen in the activism and writings of the english anarchist member of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament Alex Comfort or the similar activism of the american catholic anarcho-pacifist Ammon Hennacy. Anarcho-pacifism became a "basis for a critique of militarism on both sides of the Cold War"[93]

Contemporary anarchism

A surge of popular interest in anarchism occurred during the 1960s and 1970s.[94] Anarchism was influential in the Counterculture of the 1960s[95][96][97] and anarchists actively participated in the late sixties students and workers revolts.[98] In 1968 in Carrara, Italy the International of Anarchist Federations was founded during an international Anarchist conference held there in 1968 by the three existing European federations of France, the Italian and the Iberian Anarchist Federation as well as the Bulgarian federation in French exile.[99][100]

In the United Kingdom in the 1970s this was associated with the punk rock movement, as exemplified by bands such as Crass and the Sex Pistols.[101] The housing and employment crisis in most of Western Europe led to the formation of communes and squatter movements like that of Barcelona, Spain. In Denmark, squatters occupied a disused military base and declared the Freetown Christiania, an autonomous haven in central Copenhagen.

Since the revival of anarchism in the mid 20th century,[102] a number of new movements and schools of thought emerged. Although feminist tendencies have always been a part of the anarchist movement in the form of anarcha-feminism, they returned with vigour during the second wave of feminism in the 1960s. The American Civil Rights Movement and the movement against the war in Vietnam also contributed to the revival of North American anarchism. European anarchism of the late 20th century drew much of its strength from the labour movement, and both have incorporated animal rights activism. Anarchist anthropologist David Graeber and anarchist historian Andrej Grubacic have posited a rupture between generations of anarchism, with those "who often still have not shaken the sectarian habits" of the 19th century contrasted with the younger activists who are "much more informed, among other elements, by indigenous, feminist, ecological and cultural-critical ideas", and who by the turn of the 21st century formed "by far the majority" of anarchists.[103]

Around the turn of the 21st century, anarchism grew in popularity and influence as part of the anti-war, anti-capitalist, and anti-globalisation movements.[104] Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against the meetings of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Group of Eight, and the World Economic Forum. Some anarchist factions at these protests engaged in rioting, property destruction, and violent confrontations with police, and the confrontations were selectively portrayed in mainstream media coverage as violent riots. These actions were precipitated by ad hoc, leaderless, anonymous cadres known as black blocs; other organisational tactics pioneered in this time include security culture, affinity groups and the use of decentralised technologies such as the internet.[104] A landmark struggle of this period was the confrontations at WTO conference in Seattle in 1999.[104]

International anarchist federations in existence include the International of Anarchist Federations, the International Workers' Association, and International Libertarian Solidarity.

Anarchist schools of thought

Anarchist schools of thought had been generally grouped in two main historical traditions, individualist anarchism and social anarchism, which have some different origins, values and evolution.[2][6][105] The individualist wing of anarchism emphasises negative liberty, i.e. opposition to state or social control over the individual, while those in the social wing emphasise positive liberty to achieve one's potential and argue that humans have needs that society ought to fulfill, "recognizing equality of entitlement".[106] In chronological and theoretical sense there are classical — those created throughout the 19th century — and post-classical anarchist schools — those created since the mid-20th century and after.

Beyond the specific factions of anarchist thought is philosophical anarchism, which embodies the theoretical stance that the state lacks moral legitimacy without accepting the imperative of revolution to eliminate it. A component especially of individualist anarchism[107][108] philosophical anarchism may accept the existence of a minimal state as unfortunate, and usually temporary, "necessary evil" but argue that citizens do not have a moral obligation to obey the state when its laws conflict with individual autonomy.[109] One reaction against sectarianism within the anarchist milieu was "anarchism without adjectives", a call for toleration first adopted by Fernando Tarrida del Mármol in 1889 in response to the "bitter debates" of anarchist theory at the time.[110] In abandoning the hyphenated anarchisms (i.e. collectivist-, communist-, mutualist- and individualist-anarchism), it sought to emphasise the anti-authoritarian beliefs common to all anarchist schools of thought.[111]

Mutualism

Mutualism began in 18th century English and French labour movements before taking an anarchist form associated with Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in France and others in the United States.[112] Proudhon proposed spontaneous order, whereby organization emerges without central authority, a "positive anarchy" where order arises when everybody does "what he wishes and only what he wishes"[113] and where "business transactions alone produce the social order."[114]

Mutualist anarchism is concerned with reciprocity, free association, voluntary contract, federation, and credit and currency reform. According to William Batchelder Greene, each worker in the mutualist system would receive "just and exact pay for his work; services equivalent in cost being exchangeable for services equivalent in cost, without profit or discount."[115] Mutualism has been retrospectively characterised as ideologically situated between individualist and collectivist forms of anarchism.[116] Proudhon first characterised his goal as a "third form of society, the synthesis of communism and property."[117]

Individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism refers to several traditions of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasize the individual and their will over any kinds of external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems.[118][119] Individualist anarchism is not a single philosophy but refers to a group of individualistic philosophies that sometimes are in conflict.

In 1793, William Godwin, who has often[120] been cited as the first anarchist, wrote Political Justice, which some consider to be the first expression of anarchism.[37][121] Godwin, a philosophical anarchist, from a rationalist and utilitarian basis opposed revolutionary action and saw a minimal state as a present "necessary evil" that would become increasingly irrelevant and powerless by the gradual spread of knowledge.[37][122] Godwin advocated extreme individualism, proposing that all cooperation in labour be eliminated on the premise that this would be most conducive with the general good.[123][124]

Godwin was a utilitarian who believed that all individuals are not of equal value, with some of us "of more worth and importance" than others depending on our utility in bringing about social good. Therefore he does not believe in equal rights, but the person's life that should be favoured that is most conducive to the general good.[124] Godwin opposed government because he saw it as infringing on the individual's right to "private judgement" to determine which actions most maximise utility, but also makes a critique of all authority over the individual's judgement. This aspect of Godwin's philosophy, stripped of utilitarian motivations, was developed into a more extreme form later by Stirner.[125]

The most extreme form of individualist anarchism, called "egoism,"[126] or egoist anarchism, was expounded by one of the earliest and best-known proponents of individualist anarchism, Max Stirner.[127] Stirner's The Ego and Its Own, published in 1844, is a founding text of the philosophy.[127] According to Stirner, the only limitation on the rights of the individual is their power to obtain what they desire,[128] without regard for God, state, or morality.[129] To Stirner, rights were spooks in the mind, and he held that society does not exist but "the individuals are its reality".[130]

Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw unions of egoists, non-systematic associations continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will,[131] which Stirner proposed as a form of organization in place of the state.[132] Egoist anarchists claim that egoism will foster genuine and spontaneous union between individuals.[133] "Egoism" has inspired many interpretations of Stirner's philosophy. It was re-discovered and promoted by German philosophical anarchist and LGBT activist John Henry Mackay. Individualist anarchism inspired by Stirner attracted a small following of European bohemian artists and intellectuals[134] as well as young anarchist outlaws in what came to be known as illegalism and individual reclamation[135][136](see European individualist anarchism).

Social anarchism

Social anarchism calls for a system with public ownership of means of production and democratic control of all organizations, without any government authority or coercion. It is the largest school of thought in anarchism.[137] Social anarchism rejects private property, seeing it as a source of social inequality, and emphasises cooperation and mutual aid.[138]

Collectivist anarchism, also referred to as "revolutionary socialism" or a form of such,[139][140] is a revolutionary form of anarchism, commonly associated with Mikhail Bakunin and Johann Most.[141][142] Collectivist anarchists oppose all private ownership of the means of production, instead advocating that ownership be collectivised. This was to be achieved through violent revolution, first starting with a small cohesive group through acts of violence, or "propaganda by the deed", which would inspire the workers as a whole to revolt and forcibly collectivise the means of production.[141]

However, collectivization was not to be extended to the distribution of income, as workers would be paid according to time worked, rather than receiving goods being distributed "according to need" as in anarcho-communism. This position was criticised by anarchist communists as effectively "uphold[ing] the wages system".[143] Collectivist anarchism arose contemporaneously with Marxism but opposed the Marxist dictatorship of the proletariat, despite the stated Marxist goal of a collectivist stateless society.[144] Anarchist, communist and collectivist ideas are not mutually exclusive; although the collectivist anarchists advocated compensation for labour, some held out the possibility of a post-revolutionary transition to a communist system of distribution according to need.[145]

Anarchist communism proposes that the freest form of social organisation would be a society composed of self-managing communes with collective use of the means of production, organised democratically, and related to other communes through federation.[146] While some anarchist communists favour direct democracy, others feel that its majoritarianism can impede individual liberty and favour consensus democracy instead. In anarchist communism, as money would be abolished, individuals would not receive direct compensation for labour (through sharing of profits or payment) but would have free access to the resources and surplus of the commune.[147][148] Anarchist communism does not always have a communitarian philosophy. Some forms of anarchist communism are egoist and strongly influenced by radical individualism,[149] believing that anarchist communism does not require a communitarian nature at all.

In the early 20th century, anarcho-syndicalism arose as a distinct school of thought within anarchism.[150] With greater focus on the labour movement than previous forms of anarchism, syndicalism posits radical trade unions as a potential force for revolutionary social change, replacing capitalism and the state with a new society, democratically self-managed by the workers. It is often combined with other branches of anarchism, and anarcho-syndicalists often subscribe to anarchist communist or collectivist anarchist economic systems.[151] An early leading anarcho-syndicalist thinker was Rudolf Rocker, whose 1938 pamphlet Anarchosyndicalism outlined a view of the movement's origin, aims and importance to the future of labour.[151][152]

Post-classical currents

Anarchism continues to generate many philosophies and movements, at times eclectic, drawing upon various sources, and syncretic, combining disparate and contrary concepts to create new philosophical approaches. Since the revival of anarchism in the United States in the 1960s,[102] a number of new movements and schools have emerged.[153] Anarcho-capitalism developed from radical anti-state libertarianism and individualist anarchism, drawing from Austrian School economics, study of law and economics and public choice theory,[154] while the burgeoning feminist and environmentalist movements also produced anarchist offshoots.

Anarcha-feminism developed as a synthesis of radical feminism and anarchism that views patriarchy (male domination over women) as a fundamental manifestation of compulsory government. It was inspired by the late 19th century writings of early feminist anarchists such as Lucy Parsons, Emma Goldman, Voltairine de Cleyre, and Dora Marsden. Anarcha-feminists, like other radical feminists, criticise and advocate the abolition of traditional conceptions of family, education and gender roles. Green anarchism (or eco-anarchism)[155] is a school of thought within anarchism which puts an emphasis on environmental issues,[156] and whose main contemporary currents are anarcho-primitivism and social ecology. Anarcho-pacifism is a tendency which rejects the use of violence in the struggle for social change.[18][19] It developed "mostly in the Netherlands, Britain, and the United States, before and during the Second World War".[19]

Post-left anarchy is a tendency which seeks to distance itself from traditional left-wing politics and to escape the confines of ideology in general. Post-anarchism is a theoretical move towards a synthesis of classical anarchist theory and poststructuralist thought drawing from diverse ideas including post-modernism, autonomist marxism, post-left anarchy, situationism and postcolonialism.

Another recent form of anarchism critical of formal anarchist movements is insurrectionary anarchism,[157] which advocates informal organization and active resistance to the state; its proponents include Wolfi Landstreicher and Alfredo M. Bonanno.

Topics of interest in anarchist theory

Intersecting and overlapping between various schools of thought, certain topics of interest and internal disputes have proven perennial within anarchist theory.

Free love

An important current within anarchism is Free love.[158] Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights since most sexual laws discriminated against women: for example, marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.[158] The most important American free love journal was Lucifer the Lightbearer (1883–1907) edited by Moses Harman and Lois Waisbrooker,[159] but also there existed Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood's The Word (1872–1890, 1892–1893).[158] Free Society (1895-1897 as The Firebrand; 1897-1904 as Free Society) was a major anarchist newspaper in the United States at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries.[160] The publication staunchly advocated free love and women's rights, and critiqued "Comstockery" -- censorship of sexual information.Also M. E. Lazarus was an important American individualist anarchist who promoted free love.[158]

In New York's Greenwich Village, bohemian feminists and socialists advocated self-realisation and pleasure for women (and also men) in the here and now. They encouraged playing with sexual roles and sexuality,[161] and the openly bisexual radical Edna St. Vincent Millay and the lesbian anarchist Margaret Anderson were prominent among them. Discussion groups organised by the Villagers were frequented by Emma Goldman, among others. Magnus Hirschfeld noted in 1923 that Goldman "has campaigned boldly and steadfastly for individual rights, and especially for those deprived of their rights. Thus it came about that she was the first and only woman, indeed the first and only American, to take up the defense of homosexual love before the general public."[162] In fact, before Goldman, heterosexual anarchist Robert Reitzel (1849–1898) spoke positively of homosexuality from the beginning of the 1890s in his Detroit-based German language journal Der arme Teufel.

In Europe the main propagandist of free love within individualist anarchism was Emile Armand.[163] He proposed the concept of la camaraderie amoureuse to speak of free love as the possibility of voluntary sexual encounter between consenting adults. He was also a consistent proponent of polyamory.[163] In Germany the stirnerists Adolf Brand and John Henry Mackay were pioneering campaigners for the acceptance of male bisexuality and homosexuality.

More recently, the British anarcho-pacifist Alex Comfort gained notoriety during the sexual revolution for writing the bestseller sex manual The Joy of Sex. The issue of free love has a dedicated treatment in the work of French anarcho-hedonist philosopher Michel Onfray in such works as Théorie du corps amoureux : pour une érotique solaire (2000) and L'invention du plaisir : fragments cyréaniques (2002).

Libertarian education

Max Stirner wrote in 1842 a long essay on education called The False Principle of our Education. In it Stirner names his educational principle "personalist," explaining that self-understanding consists in hourly self-creation. Education for him is to create "free men, sovereign characters," by which he means "eternal characters...who are therefore eternal because they form themselves each moment".[164]

In 1901, Catalan anarchist and free-thinker Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia established "modern" or progressive schools in Barcelona in defiance of an educational system controlled by the Catholic Church.[165] The schools' stated goal was to "educate the working class in a rational, secular and non-coercive setting". Fiercely anti-clerical, Ferrer believed in "freedom in education", education free from the authority of church and state.[166] Murray Bookchin wrote: "This period [1890s] was the heyday of libertarian schools and pedagogical projects in all areas of the country where Anarchists exercised some degree of influence. Perhaps the best-known effort in this field was Francisco Ferrer's Modern School (Escuela Moderna), a project which exercised a considerable influence on Catalan education and on experimental techniques of teaching generally."[167] La Escuela Moderna, and Ferrer's ideas generally, formed the inspiration for a series of Modern Schools in the United States,[165] Cuba, South America and London. The first of these was started in New York City in 1911. It also inspired the Italian newspaper Università popolare, founded in 1901.

Another libertarian tradition is that of unschooling and the free school in which child-led activity replaces pedagogic approaches. Experiments in Germany led to A. S. Neill founding what became Summerhill School in 1921.[168] Summerhill is often cited as an example of anarchism in practice.[169] However, although Summerhill and other free schools are radically libertarian, they differ in principle from those of Ferrer by not advocating an overtly political class struggle-approach.[170] In addition to organizing schools according to libertarian principles, anarchists have also questioned the concept of schooling per se. The term deschooling was popularized by Ivan Illich, who argued that the school as an institution is dysfunctional for self-determined learning and serves the creation of a consumer society instead.[171]

Internal issues and debates

Anarchism is a philosophy which embodies many diverse attitudes, tendencies and schools of thought; as such, disagreement over questions of values, ideology and tactics is common. The compatibility of capitalism,[4] nationalism and religion with anarchism is widely disputed. Similarly, anarchism enjoys complex relationships with ideologies such as Marxism, communism and capitalism. Anarchists may be motivated by humanism, divine authority, enlightened self-interest, veganism or any number of alternative ethical doctrines.

Phenomena such as civilization, technology (e.g. within anarcho-primitivism and insurrectionary anarchism), and the democratic process may be sharply criticised within some anarchist tendencies and simultaneously lauded in others.

On a tactical level, while propaganda of the deed was a tactic used by anarchists in the 19th century (e.g. the Nihilist movement), contemporary anarchists espouse alternative direct action methods such as nonviolence, counter-economics and anti-state cryptography to bring about an anarchist society. About the scope of an anarchist society, some anarchists advocate a global one, while others do so by local ones.[172] The diversity in anarchism has led to widely different use of identical terms among different anarchist traditions, which has led to many definitional concerns in anarchist theory.

Related pages

- Anarchist symbolism

- Lists of anarchism topics

- List of anarchist communities

- List of anarchist movements by region

Footnotes

- ^

Malatesta, Errico. "Towards Anarchism". MAN!. Los Angeles: International Group of San Francisco. OCLC 3930443.

Agrell, Siri (2007-05-14). "Working for The Man". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

"Anarchism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

"Anarchism". The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: 14. 2005.

Anarchism is the view that a society without the state, or government, is both possible and desirable.

The following sources cite anarchism as a political philosophy: Mclaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 59. ISBN 0-7546-6196-2. Johnston, R. (2000). The Dictionary of Human Geography. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 0-631-20561-6. - ^ a b c Slevin, Carl. "Anarchism." The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Ed. Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ^ Ward, Colin (1966). "Anarchism as a Theory of Organization". Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Anarchism." The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Sylvan, Richard (1995). "Anarchism". A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy. Philip. Blackwell Publishing. p. 231.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Ostergaard, Geoffrey. "Anarchism". The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 14.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (2002). Anarchism: A Collection of Revolutionary Writings. Courier Dover Publications. p. 5. ISBN 0-486-41955-X.R.B. Fowler (1972). "The Anarchist Tradition of Political Thought". Western Political Quarterly. 25 (4). University of Utah: 738–752. doi:10.2307/446800. JSTOR 10.2307/446800.

- ^ Brooks, Frank H. (1994). The Individualist Anarchists: An Anthology of Liberty (1881–1908). Transaction Publishers. p. xi. ISBN 1-56000-132-1.

Usually considered to be an extreme left-wing ideology, anarchism has always included a significant strain of radical individualism, from the hyperrationalism of Godwin, to the egoism of Stirner, to the libertarians and anarcho-capitalists of today

- ^ Joseph Kahn (2000). "Anarchism, the Creed That Won't Stay Dead; The Spread of World Capitalism Resurrects a Long-Dormant Movement". The New York Times (5 August).Colin Moynihan (2007). "Book Fair Unites Anarchists. In Spirit, Anyway". New York Times (16 April).

- ^ Stringham, Edward (2007). Anarchy and the Law. The Political Economy of Choice. Transaction Publishers. p. 720.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title=|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Narveson, Jan (2002). Respecting Persons in Theory and Practice. Chapter 11: Anarchist's Case. "To see this, of course, we must expound the moral outlook underlying anarchism. To do this we must first make an important distinction between two general options in anarchist theory [...] The two are what we may call, respectively, the socialist versus the free-market, or capitalist, versions."

- ^ Tormey, Simon, Anti-Capitalism, A Beginner's Guide, Oneworld Publications, 2004, pp. 118–119.

- ^ "This stance puts him squarely in the libertarian socialist tradition and, unsurprisingly, Tucker referred to himself many times as a socialist and considered his philosophy to be "Anarchistic socialism." "An Anarchist FAQby Various Authors

- ^ "Because revolution is the fire of our will and a need of our solitary minds; it is an obligation of the libertarian aristocracy. To create new ethical values. To create new aesthetic values. To communalize material wealth. To individualize spiritual wealth." Renzo Novatore. Toward the Creative Nothing

- ^ "Daniel Guérin Anarchism: From Theory to Practice". Theanarchistlibrary.org. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ A.3 What types of anarchism are there?. in An Anarchist FAQ

- ^ Skirda, Alexandre. Facing the Enemy: A History of Anarchist Organization from Proudhon to May 1968. AK Press, 2002, p. 191.

- ^ a b ""Resiting the Nation State, the pacifist and anarchist tradition" by Geoffrey Ostergaard". Ppu.org.uk. 1945-08-06. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ a b c d George Woodcock. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (1962)

- ^ Fowler, R.B. "The Anarchist Tradition of Political Thought." The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4. (December, 1972), pp. 743–744.

- ^ Anarchy. Merriam-Webster online.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George, & Scott, Robert, "A Greek-English Lexicon"[1].

- ^ Liddell, Henry George. A Greek-English Lexicon. ISBN 0-19-910205-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nettlau, Max (1996). A Short History of Anarchism. Freedom Press. p. 162. ISBN 0-900384-89-1.

- ^ Russell, Dean. Who is a Libertarian?, Foundation for Economic Education, "Ideas on Liberty," May, 1955.

- ^

- Ward, Colin. Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press 2004 p. 62

- Goodway, David. Anarchists Seed Beneath the Snow. Liverpool Press. 2006, p. 4

- MacDonald, Dwight & Wreszin, Michael. Interviews with Dwight Macdonald. University Press of Mississippi, 2003. p. 82

- Bufe, Charles. The Heretic's Handbook of Quotations. See Sharp Press, 1992. p. iv

- Gay, Kathlyn. Encyclopedia of Political Anarchy. ABC-CLIO / University of Michigan, 2006, p. 126

- Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Broadview Press, 2004. (Uses the terms interchangeably, such as on page 10)

- Skirda, Alexandre. Facing the Enemy: A History of Anarchist Organization from Proudhon to May 1968. AK Press 2002. p. 183.

- Fernandez, Frank. Cuban Anarchism. The History of a Movement. See Sharp Press, 2001, page 9.

- ^ Perlin, Terry M. (1979). Contemporary Anarchism. Transaction Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 0-87855-097-6.

- ^ Noam Chomsky, Carlos Peregrín Otero. Language and Politics. AK Press, 2004, p. 739.

- ^ Morris, Christopher. 1992. An Essay on the Modern State. Cambridge University Press. p. 61. (Using "libertarian anarchism" synonymously with "individualist anarchism" when referring to individualist anarchism that supports a market society).

- ^ Burton, Daniel C. Libertarian anarchism. Libertarian Alliance.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b c d Peter Kropotkin, "Anarchism", Encyclopædia Britannica 1910.

- ^ Murray Rothbard. "Concepts of the role of intellectuals in social change toward laissez faire" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ Julie Piering. "Cynics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b c d e "Anarchism", BBC Radio 4 program, In Our Time, Thursday 7 December 2006. Hosted by Melvyn Bragg of the BBC, with John Keane, Professor of Politics at University of Westminster, Ruth Kinna, Senior Lecturer in Politics at Loughborough University, and Peter Marshall, philosopher and historian.

- ^ Sheehan, Sean. Anarchism, London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2004. p. 85.

- ^ "Anarchism", Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006 (UK version).

- ^ a b c Mark Philip (2006-05-20). "William Godwin". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Godwin himself attributed the first anarchist writing to Edmund Burke's A Vindication of Natural Society. "Most of the above arguments may be found much more at large in Burke's Vindication of Natural Society; a treatise in which the evils of the existing political institutions are displayed with incomparable force of reasoning and lustre of eloquence..." – footnote, Ch. 2 Political Justice by William Godwin.

- ^ Liberty XIV (December, 1900:1).

- ^ Daniel Guerin, Anarchism: From Theory to Practice (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970).

- ^ Jonathan Purkis and James Bowen, "Introduction: Why Anarchism Still Matters", in Jonathan Purkis and James Bowen (eds), Changing Anarchism: Anarchist Theory and Practice in a Global Age (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), p. 3.

- ^ Breunig, Charles (1977). The Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1789–1850. New York, N.Y: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-09143-0.

- ^ Blin, Arnaud (2007). The History of Terrorism. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-520-24709-4.

- ^ Dodson, Edward (2002). The Discovery of First Principles: Volume 2. Authorhouse. p. 312. ISBN 0-595-24912-4.

- ^ Thomas, Paul (1985). Karl Marx and the Anarchists. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 187. ISBN 0-7102-0685-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Thomas, Paul (1980). Karl Marx and the Anarchists. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. p. 304. ISBN 0-7102-0685-2.

- ^ Bak, Jǹos (1991). Liberty and Socialism. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 236. ISBN 0-8476-7680-3.

- ^ Engel, Barbara (2000). Mothers and Daughters. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-8101-1740-1.

- ^ a b "On the International Workingmen's Association and Karl Marx" in Bakunin on Anarchy, translated and edited by Sam Dolgoff, 1971.

- ^ Bakunin, Mikhail (1991) [1873]. Statism and Anarchy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36973-8.

- ^ Graham, Robert 'Anarchism (Montreal: Black Rose Books 2005) ISBN 1-55164-251-4.

- ^ Resolutions from the St. Imier Congress, in Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, Vol. 1, p. 100 [2]

- ^ a b c Foner, Philip Sheldon (1986). May day: a short history of the international workers' holiday, 1886–1986. New York: International Publishers. p. 56. ISBN 0-7178-0624-3.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (1984). The Haymarket Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-691-00600-8.

- ^ Avrich. The Haymarket Tragedy. p. 193. ISBN 0-691-04711-1.

- ^ "Patrolman Mathias J. Degan". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ^ Chicago Tribune, 27 June 1886, quoted in Avrich. The Haymarket Tragedy. p. 209. ISBN 0-691-04711-1.

- ^ "Act II: Let Your Tragedy Be Enacted Here". The Dramas of Haymarket. Chicago Historical Society. 2000. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ^ Foner. May Day. p. 42. ISBN 0-7178-0624-3.

- ^ Extract of Malatesta's declaration Template:Fr icon

- ^ Skirda, Alexandre (2002). Facing the enemy: a history of anarchist organization from Proudhon to May 1968. A. K. Press. p. 89. ISBN 1-902593-19-7.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-297-84832-5.

- ^ Carley, Mark "Trade union membership 1993–2003" (International:SPIRE Associates 2004).

- ^ ""Action as Propaganda" by Johann Most, July 25, 1885". Dwardmac.pitzer.edu. 2003-04-21. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ "Anarchist-Communism" by Alain Pengam

- ^ "The "illegalists" by Doug Imrie. From "Anarchy: a Journal Of Desire Armed" , Fall-Winter, 1994-95

- ^ quoted in Billington, James H. 1998. Fire in the minds of men: origins of the revolutionary faith New Jersey: Transaction Books, p 417.

- ^ "Table Of Contents". Blackrosebooks.net. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Historian Benedict Anderson thus writes:

According to some analysts, in post-war Germany, the prohibition of the Communist Party (KDP) and thus of institutional far-left political organization may also, in the same manner, have played a role in the creation of the Red Army Faction."In March 1871 the Commune took power in the abandoned city and held it for two months. Then Versailles seized the moment to attack and, in one horrifying week, executed roughly 20,000 Communards or suspected sympathizers, a number higher than those killed in the recent war or during Robespierre's 'Terror' of 1793–1794. More than 7,500 were jailed or deported to places like New Caledonia. Thousands of others fled to Belgium, England, Italy, Spain and the United States. In 1872, stringent laws were passed that ruled out all possibilities of organizing on the left. Not till 1880 was there a general amnesty for exiled and imprisoned Communards. Meanwhile, the Third Republic found itself strong enough to renew and reinforce Louis Napoleon's imperialist expansion– in Indochina, Africa, and Oceania. Many of France's leading intellectuals and artists had participated in the Commune (Courbet was its quasi-minister of culture, Rimbaud and Pissarro were active propagandists) or were sympathetic to it. The ferocious repression of 1871 and thereafter, was probably the key factor in alienating these milieux from the Third Republic and stirring their sympathy for its victims at home and abroad." (in Benedict Anderson (July -August 2004). "In the World-Shadow of Bismarck and Nobel". New Left Review.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)) - ^ Dirlik, Arif (1991). Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07297-9.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (2006). The Russian Anarchists. Stirling: AK Press. p. 204. ISBN 1-904859-48-8.

- ^ Goldman, Emma (2003). "Preface". My Disillusionment in Russia. New York: Dover Publications. p. xx. ISBN 0-486-43270-X.

My critic further charged me with believing that "had the Russians made the Revolution à la Bakunin instead of à la Marx" the result would have been different and more satisfactory. I plead guilty to the charge. In truth, I not only believe so; I am certain of it.

- ^ Nomad, Max (1966). "The Anarchist Tradition title = Revolutionary Internationals 1864 1943". In Drachkovitch, Milorad M. (ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-8047-0293-4.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Missing pipe in:|contribution=(help) - ^ Dielo Trouda (2006) [1926]. Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft). Italy: FdCA. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ a b c — Starhawk. ""J.3.2 What are "synthesis" federations?" in [[An Anarchist FAQ]]". Infoshop.org. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Holbrow, Marnie, "Daring but Divided" (Socialist Review November 2002).

- ^ Berry, David. "Fascism or Revolution." Le Libertaire. August 1936.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-297-84832-5.

- ^ Bolloten, Burnett (1984-11-15). The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution. University of North Carolina Press. p. 1107. ISBN 978-0-8078-1906-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Birchall, Ian (2004). Sartre Against Stalinism. Berghahn Books. p. 29. ISBN 1-57181-542-2.

- ^ "Anarchist Activity in France during World War Two"

- ^ "1943-1945: Anarchist partisans in the Italian Resistance"

- ^ "El mapa del despertar anarquista: su expresión latinoamericana" by Daniel Barret and "Mexico 1939: Anarchist Federation of the Centre"[3]

- ^ "The surviving sectors of the revolutionary anarchist movement of the 1920-1940 period, now working in the SIA and the FGAC, reinforced by those Cuban militants and Spanish anarchists fleeing now-fascist Spain, agreed at the beginning of the decade to hold an assembly with the purpose of regrouping the libertarian forces inside a single organization. The guarantees of the 1940 Constitution permitted them to legally create an organization of this type, and it was thus that they agreed to dissolve the two principal Cuban anarchist organizations, the SIA and FGAC, and create a new, unified group, the Asociación Libertaria de Cuba (ALC), a sizable organization with a membership in the thousands."Cuban Anarchism: The History of A Movement by Frank Fernandez

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5]

- ^ THE ANARCHIST MOVEMENT IN JAPAN Anarchist Communist Editions § ACE Pamphlet No. 8

- ^ [6]

- ^ "50 años de la Federación Anarquista Uruguaya"

- ^ "It was in the black mirror of anarchism that surrealism first recognised itself," wrote André Breton in "The Black Mirror of Anarchism," Selection 23 in Robert Graham, ed., Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, Volume Two: The Emergence of the New Anarchism (1939-1977)[7]. Breton had returned to France in 1947 and in April of that year Andre Julien welcomed his return in the pages of Le Libertaire the weekly paper of the Federation Anarchiste""1919-1950: The politics of Surrealism" by Nick Heath

- ^ "In the forties and fifties, anarchism, in fact if not in name, began to reappear, often in alliance with pacifism, as the basis for a critique of militarism on both sides of the Cold War.[8] The anarchist/pacifist wing of the peace movement was small in comparison with the wing of the movement that emphasized electoral work, but made an important contribution to the movement as a whole. Where the more conventional wing of the peace movement rejected militarism and war under all but the most dire circumstances, the anarchist/pacifist wing rejected these on principle.""Anarchism and the Anti-Globalization Movement" by Barbara Epstein

- ^ "In the 1950s and 1960s anarcho-pacifism began to gel, tough-minded anarchists adding to the mixture their critique of the state, and tender-minded pacifists their critique of violence. Its first practical manifestation was at the level of method: nonviolent direct action, principled and pragmatic, was used widely in both the Civil Rights movement in the USA and the campaign against nuclear weapons in Britain and elsewhere."Geoffrey Ostergaard. Resisting the Nation State. The pacifist and anarchist tradition

- ^ "Anarchism and the Anti-Globalization Movement" by Barbara Epstein

- ^ Thomas 1985, p. 4 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThomas1985 (help)

- ^ "These groups had their roots in the anarchist resurgence of the nineteen sixties. Young militants finding their way to anarchism, often from the anti-bomb and anti-Vietnam war movements, linked up with an earlier generation of activists, largely outside the ossified structures of ‘official’ anarchism. Anarchist tactics embraced demonstrations, direct action such as industrial militancy and squatting, protest bombings like those of the First of May Group and Angry Brigade – and a spree of publishing activity.""Islands of Anarchy: Simian, Cienfuegos, Refract and their support network" by John Patten

- ^ "Farrell provides a detailed history of the Catholic Workers and their founders Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin. He explains that their pacifism, anarchism, and commitment to the downtrodden were one of the important models and inspirations for the 60s. As Farrell puts it, "Catholic Workers identified the issues of the sixties before the Sixties began, and they offered models of protest long before the protest decade.""The Spirit of the Sixties: The Making of Postwar Radicalism" by James J. Farrell

- ^ "While not always formally recognized, much of the protest of the sixties was anarchist. Within the nascent women's movement, anarchist principles bcame so widespread that a political science profes- sor denounced what she saw as "The Tyranny of Structurelessness." Several groups have called themselves "Amazon Anarchists." After the Stonewall Rebellion, the New York Gay Liberation Front based their organization in part on a reading of Murray Bookchin's anarchist writings." [http://www.williamapercy.com/wiki/images/Anarchism.pdf "Anarchism" by Charley Shively in Encyclopedia of Homosexuality. pg. 52

- ^ "Within the movements of the sixties there was much more receptivity to anarchism-in-fact than had existed in the movements of the thirties...But the movements of the sixties were driven by concerns that were more compatible with an expressive style of politics, with hostility to authority in general and state power in particular...By the late sixties, political protest was intertwined with cultural radicalism based on a critique of all authority and all hierarchies of power. Anarchism circulated within the movement along with other radical ideologies. The influence of anarchism was strongest among radical feminists, in the commune movement, and probably in the Weather Underground and elsewhere in the violent fringe of the anti-war movement." "Anarchism and the Anti-Globalization Movement" by Barbara Epstein

- ^ London Federation of Anarchists involvement in Carrara conference, 1968 International Institute of Social History, Accessed 19 January 2010

- ^ Short history of the IAF-IFA A-infos news project, Accessed 19 January 2010

- ^ McLaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 10. ISBN 0-7546-6196-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ a b Williams, Leonard (2007). "Anarchism Revived". New Political Science. 29 (3): 297–312. doi:10.1080/07393140701510160.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "revival" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ David Graeber and Andrej Grubacic, "Anarchism, Or The Revolutionary Movement Of The Twenty-first Century", ZNet. Retrieved 2007-12-13. or Graeber, David and Grubacic, Andrej(2004)Anarchism, Or The Revolutionary Movement Of The Twenty-first Century Retrieved 2010-07-26

- ^ a b c Rupert, Mark (2006). Globalization and International Political Economy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 66. ISBN 0-7425-2943-6.

- ^ Anarchism, The New Encyclopedia of Social Reform (1908).

- ^ Harrison, Kevin and Boyd, Tony. Understanding Political Ideas and Movements. Manchester University Press 2003, p. 251.

- ^ Outhwaite, William & Tourain, Alain (Eds.). (2003). Anarchism. The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought (2nd Edition, p. 12). Blackwell Publishing.

- ^ Wayne Gabardi, review of Anarchism by David Miller, published in American Political Science Review Vol. 80, No. 1. (Mar., 1986), pp. 300-302.

- ^ Klosko, George. Political Obligations. Oxford University Press 2005. p. 4.

- ^ Avrich, Paul. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America. Princeton University Press, 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Esenwein, George Richard "Anarchist Ideology and the Working Class Movement in Spain, 1868–1898" [p. 135].

- ^ "A member of a community," The Mutualist; this 1826 series criticised Robert Owen's proposals, and has been attributed to a dissident Owenite, possibly from the Friendly Association for Mutual Interests of Valley Forge; Wilbur, Shawn, 2006, "More from the 1826 "Mutualist"?".

- ^ Proudhon, Solution to the Social Problem, ed. H. Cohen (New York: Vanguard Press, 1927), p. 45.

- ^ Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1979). The Principle of Federation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5458-7.

The notion of anarchy in politics is just as rational and positive as any other. It means that once industrial functions have taken over from political functions, then business transactions alone produce the social order.

- ^ "Communism versus Mutualism", Socialistic, Communistic, Mutualistic and Financial Fragments. (Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1875) William Batchelder Greene: "Under the mutual system, each individual will receive the just and exact pay for his work; services equivalent in cost being exchangeable for services equivalent in cost, without profit or discount; and so much as the individual laborer will then get over and above what he has earned will come to him as his share in the general prosperity of the community of which he is an individual member."

- ^ Avrich, Paul. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America, Princeton University Press 1996 ISBN 0-691-04494-5, p.6

Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought, Blackwell Publishing 1991 ISBN 0-631-17944-5, p. 11. - ^ Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. What Is Property? Princeton, MA: Benjamin R. Tucker, 1876. p. 281.

- ^ "What do I mean by individualism? I mean by individualism the moral doctrine which, relying on no dogma, no tradition, no external determination, appeals only to the individual conscience."Mini-Manual of Individualism by Han Ryner

- ^ "I do not admit anything except the existence of the individual, as a condition of his sovereignty. To say that the sovereignty of the individual is conditioned by Liberty is simply another way of saying that it is conditioned by itself.""Anarchism and the State" in Individual Liberty

- ^ Everhart, Robert B. The Public School Monopoly: A Critical Analysis of Education and the State in American Society. Pacific Institute for Public Policy Research, 1982. p. 115.

- ^ Adams, Ian. Political Ideology Today. Manchester University Press, 2001. p. 116.

- ^ Godwin, William (1796) [1793]. Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Modern Morals and Manners. G.G. and J. Robinson. OCLC 2340417.

- ^ Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 December 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ a b Paul McLaughlin. Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2007. p. 119.

- ^ Paul McLaughlin. Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2007. p. 123.

- ^ Goodway, David. Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow. Liverpool University Press, 2006, p. 99.

- ^ a b David Leopold (2006-08-04). "Max Stirner". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana: A Library of Universal Knowledge. Encyclopedia Corporation. p. 176.

- ^ Miller, David. "Anarchism." 1987. The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 11.

- ^ "What my might reaches is my property; and let me claim as property everything I feel myself strong enough to attain, and let me extend my actual property as fas as I entitle, that is, empower myself to take..." In Ossar, Michael. 1980. Anarchism in the Dramas of Ernst Toller. SUNY Press. p. 27.

- ^ Nyberg, Svein Olav. "max stirner". Non Serviam. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ Thomas, Paul (1985). Karl Marx and the Anarchists. London: Routledge/Kegan Paul. p. 142. ISBN 0-7102-0685-2.

- ^ Carlson, Andrew (1972). "Philosophical Egoism: German Antecedents". Anarchism in Germany. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-0484-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "2. Individualist Anarchism and Reaction" in Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism - An Unbridgeable Chasm

- ^ The "Illegalists", by Doug Imrie (published by Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed)

- ^ Parry, Richard. The Bonnot Gang. Rebel Press, 1987. p. 15

- ^ "This does not mean that the majority thread within the anarchist movement is uncritical of individualist anarchism. Far from it! Social anarchists have argued that this influence of non-anarchist ideas means that while its "criticism of the State is very searching, and [its] defence of the rights of the individual very powerful," like Spencer it "opens . . . the way for reconstituting under the heading of 'defence' all the functions of the State." Section G – Is individualist anarchism capitalistic? An Anarchist FAQ

- ^ Ostergaard, Geoffrey. "Anarchism". A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Blackwell Publishing, 1991. p. 21.

- ^ Morris, Brian. Bakunin: The Philosophy of Freedom. Black Rose Books Ltd., 1993. p. 76.

- ^ Rae, John. Contemporary Socialism. C. Scribner's sons, 1901, Original from Harvard University. p. 261.

- ^ a b Patsouras, Louis. 2005. Marx in Context. iUniverse. p. 54.

- ^ Avrich, Paul. 2006. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America. AK Press. p. 5.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (2007). "13". The Conquest of Bread. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-904859-10-9.

- ^ Bakunin, Mikhail (1990). Statism and Anarchy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36182-6.

They [the Marxists] maintain that only a dictatorship – their dictatorship, of course – can create the will of the people, while our answer to this is: No dictatorship can have any other aim but that of self-perpetuation, and it can beget only slavery in the people tolerating it; freedom can be created only by freedom, that is, by a universal rebellion on the part of the people and free organization of the toiling masses from the bottom up.

- ^ Guillaume, James (1876). "Ideas on Social Organization".

- ^ Puente, Isaac."Libertarian Communism". The Cienfuegos Press Anarchist Review. Issue 6 Orkney 1982.

- ^ Miller. Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought, Blackwell Publishing (1991) ISBN 0-631-17944-5, p. 12.

- ^ Graeber, David and Grubacic, Andrej. Anarchism, Or The Revolutionary Movement Of The Twenty-first Century.

- ^ Christopher Gray, Leaving the Twentieth Century, p. 88.

- ^ Berry, David, A History of the French Anarchist Movement, 1917–1945 p. 134.

- ^ Anarchosyndicalism by Rudolf Rocker. Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- ^ Perlin, Terry M. Contemporary Anarchism. Transaction Books, New Brunswick, NJ 1979

- ^ Edward Stringham, Anarchy, State, and Public Choice, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2005.

- ^ David Pepper (1996). Modern Environmentalism p. 44. Routledge.

- ^ Ian Adams (2001). Political Ideology Today p. 130. Manchester University Press.

- ^ ""Anarchism, insurrections and insurrectionalism" by Joe Black". Ainfos.ca. 2006-07-19. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ a b c d "The Free Love Movement and Radical Individualism By Wendy McElroy". Ncc-1776.org. 1996-12-01. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Joanne E. Passet, "Power through Print: Lois Waisbrooker and Grassroots Feminism," in: Women in Print: Essays on the Print Culture of American Women from the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, James Philip Danky and Wayne A. Wiegand, eds., Madison, WI, University of Wisconsin Press, 2006; pp. 229–250.

- ^ "Free Society was the principal English-language forum for anarchist ideas in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century." Emma Goldman: Making Speech Free, 1902-1909, p.551.

- ^ Sochen, June. 1972. The New Woman: Feminism in Greenwich Village 1910–1920. New York: Quadrangle.

- ^ Katz, Jonathan Ned. Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1976)

- ^ a b "E. Armand and "la camaraderie amoureuse" – Revolutionary sexualism and the struggle against jealousy" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ ""The False Principle of our Education" by Max Stirner". Tmh.floonet.net. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ a b Geoffrey C. Fidler (1985). "The Escuela Moderna Movement of Francisco Ferrer: "Por la Verdad y la Justicia"". History of Education Quarterly. 25 (1/2). History of Education Society: 103–132. doi:10.2307/368893. JSTOR 10.2307/368893.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Francisco Ferrer's Modern School". Flag.blackened.net. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Chapter 7, Anarchosyndicalism, The New Ferment. In Murray Bookchin, The Spanish anarchists: the heroic years, 1868–1936. AK Press, 1998, p.115. ISBN 1-873176-04-X

- ^ Purkis, Jon (2004). Changing Anarchism. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6694-8.

- ^ Andrew Vincent (2010) Modern Political Ideologies, 3rd edition, Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell p.129

- ^ Suissa, Judith (2005). "Anarchy in the classroom". The New Humanist. 120 (5).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Illich, Ivan (1971). Deschooling Society. New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-012139-4.

- ^ Ted Honderich, Carmen García Trevijano, Oxford Enciclopedy of Philosophy.

Further reading

- Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas. Robert Graham, editor.

- Volume One: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300CE to 1939) Black Rose Books, Montréal and London 2005. ISBN 1-55164-250-6.

- Volume Two: The Anarchist Current (1939–2006) Black Rose Books, Montréal 2007. ISBN 978-1-55164-311-3.

- Anarchism, George Woodcock (Penguin Books, 1962). OCLC 221147531.

- Anarchy: A Graphic Guide, Clifford Harper (Camden Press, 1987): An overview, updating Woodcock's classic, and illustrated throughout by Harper's woodcut-style artwork.

- The Anarchist Reader, George Woodcock (ed.) (Fontana/Collins 1977; ISBN 0-00-634011-3): An anthology of writings from anarchist thinkers and activists including Proudhon, Kropotkin, Bakunin, Malatesta, Bookchin, Goldman, and many others.

- Anarchism: From Theory to Practice by Daniel Guerin. Monthly Review Press. 1970. ISBN 0-85345-175-3

- Anarchy through the times by Max Nettlau. Gordon Press. 1979. ISBN 0-8490-1397-6

- Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism by Peter Marshall. PM Press. 2010. ISBN 1-60486-064-2

- People Without Government: An Anthropology of Anarchy (2nd ed.) by Harold Barclay, Left Bank Books, 1990 ISBN 1-871082-16-1

- The Political Theory of Anarchism by April Carter. Harper & Row. 1971. ISBN 978-0-0613-6050-3

- Sartwell, Crispin (2008). Against the state: an introduction to anarchist political theory. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791474471.

External links

- Infoshop.org - the largest online collection of news and information about anarchism.

- Anarchism on In Our Time at the BBC

- "An Anarchist FAQ Webpage" –An Anarchist FAQ

- Anarchist Theory FAQ –by Bryan Caplan

- The Anarchist Library large online library with texts from anarchist authors

- Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia –700+ entries, with short biographies, links and dedicated pages

- Anarchy Archives – information relating to famous anarchists including their writings (see Anarchy Archives).

- KateSharpleyLibrary.net –website of the Kate Sharpley Library, containing many historical documents pertaining to anarchism

- They Lie We Die –anarchist virtual library containing 768 books, booklets and texts

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA