Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire | |

|---|---|

| 1526–1858 | |

Mughal Empire (green) during its greatest territorial extent, c. 1700 | |

| Capital | Agra; Fatehpur Sikri; Delhi |

| Common languages | Persian (initially also Chagatai Turkic; later also Urdu) |

| Government | Absolute monarchy, unitary state with federal structure |

| Emperor | |

• 1526–1530 | Babur |

• 1530–1539, 1555–1556 | Humayun |

• 1556–1605 | Akbar |

• 1605–1627 | Jahangir |

• 1628–1658 | Shah Jahan |

• 1658–1707 | Aurangzeb |

| Historical era | Early modern |

• First Battle of Panipat | 21 April 1526 |

• Indian Rebellion of 1857 | 20 June 1858 |

| Area | |

| 1700 | 3,200,000 km2 (1,200,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1700 | 150,000,000 |

| Currency | Rupee |

| Today part of | |

Population source:[1] | |

Template:South Asian history The Mughal Empire (RV7H+29V Bidokht, South Khorasan Province bidokht, [Shāhān-e Moġul] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Template:Lang-ur; self-designation: گوركانى, [Gūrkānī] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)),[2][3] or Mogul (also Moghul) Empire in former English usage, was an imperial power from the Indian Subcontinent.[4] The Mughal emperors were descendants of the Timurids. It began in 1526, at the height of their power in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, they controlled most of the Indian Subcontinent—extending from Bengal in the east to Balochistan in the west, Kashmir in the north to the Kaveri basin in the south.[5] Its population at that time has been estimated as between 110 and 150 million, over a territory of more than 3.2 million square kilometres (1.2 million square miles).[1]

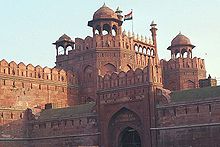

The "classic period" of the empire started in 1556 with the accession of Jalaluddin Mohammad Akbar, better known as Akbar the Great. Under the rule of Akbar the Great, India enjoyed much cultural and economic progress as well as religious harmony. The Mughals also forged a strategic alliance with several Hindu Rajputs kingdoms. However, some Rajput kings, such as Maha Rana Pratap, continued to pose significant threat to Mughal dominance of northwestern India. Additionally, regional states in southern and northeastern India, such as the Ahom Kingdom of Assam, successfully resisted Mughal subjugation. The reign of Shah Jahan, the fifth emperor, was the golden age of Mughal architecture. He erected many splendid monuments, the most famous of which is the legendary Taj Mahal at Agra as well as Pearl Mosque, the Red Fort, Jama Masjid (Mosque) and Lahore Fort. The reign of Aurangzeb saw the enforcement of strict Muslim fundamentalism which caused rebellions among the Sikhs and Hindus.

By early 1700s, the Sikh Misl and the Hindu Maratha Empire had emerged as formidable foes of the Mughals. Following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the empire started its gradual decline,[6] although the dynasty continued for another 150 years. During the classic period, the empire was marked by a highly centralized administration connecting the different regions. All the significant monuments of the Mughals, their most visible legacy, with brilliant literary, artistic, and architectural results.

Following 1725, the empire began to disintegrate, weakened by wars of succession, agrarian crises fueling local revolts, the growth of religious intolerance, the rise of the Maratha, Durrani, as well as Sikh empires and finally British colonialism. The last Emperor, Bahadur Shah II, whose rule was restricted to the city of Delhi, was imprisoned and exiled by the British after the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

The name Mughal is derived from the original homelands of the Timurids, the Central Asian steppes once conquered by Genghis Khan and hence known as Moghulistan, "Land of Mongols". Although early Mughals spoke the Chagatai language and maintained some Turko-Mongol practices, they became essentially Persianized[7] and transferred the Persian literary and high culture[7] to India, thus forming the base for the Indo-Persian culture.[7]

Early history

Zahir ud-din Muhammad Babur learned about the riches of Hindustan and conquest of it by his ancestor, Timur Lang, in 1503 at Dikh-Kat, a place in the Transoxiana region. At that time, he was roaming as a wanderer after losing his principality, Farghana. In his memoirs he wrote that after he had acquired Kabul (in 1514), he desired to regain the territories in Hindustan held once by Turks. He started his exploratory raids from September 1519 when he visited the Indo-Afghan borders to suppress the rising by Yusufzai tribes. He undertook similar raids up to 1524 and had established his base camp at Peshawar. In 1526, Babur defeated the last of the Delhi Sultans, Ibrahim Shah Lodi, at the First Battle of Panipat. To secure his newly founded kingdom, Babur then had to face the formidable Rajput Rana Sanga of Chittor, at the Battle of Khanwa. Rana Sanga offered stiff resistance but was defeated.

Babur's son Humayun succeeded him in 1530, but suffered reversals at the hands of the Pashtun Sher Shah Suri and lost most of the fledgling empire before it could grow beyond a minor regional state. From 1540 Humayun became ruler in exile, reaching the court of the Safavid rule in 1554 while his force still controlled some fortresses and small regions. But when the Pashtuns fell into disarray with the death of Sher Shah Suri, Humayun returned with a mixed army, raised more troops, and managed to reconquer Delhi in 1555.

Humayun crossed the rough terrain of the Makran with his wife. The resurgent Humayun then conquered the central plateau around Delhi, but months later died in an accident, leaving the realm unsettled and in war.

Akbar succeeded his father on 14 February 1556, while in the midst of a war against Sikandar Shah Suri for the throne of Delhi. He soon won his eighteenth victory at age 21 or 22. He became known as Akbar, as he was a wise ruler, setting high but fair taxes. He was a more inclusive in his approach to the non-Muslim subjects of the Empire. He investigated the production in a certain area and taxed inhabitants one-fifth of their agricultural produce. He also set up an efficient bureaucracy and was tolerant of religious differences which softened the resistance by the locals. He made alliances with Rajputs and appointed native generals and administrators. Later in life, he devised his own brand of syncretic philosophy based on tolerance.

Jahangir, son of Emperor Akbar, ruled the empire from 1605–1627. In October 1627, Shah Jahan, son of Emperor Jahangir succeeded to the throne, where he inherited a vast and rich empire. At mid-century this was perhaps the greatest empire in the world. Shah Jahan commissioned the famous Taj Mahal (1630–1653) in Agra which was built by the Persian architect Ustad Ahmad Lahauri as a tomb for Shah Jahan's wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died giving birth to their 14th child. By 1700 the empire reached its peak under the leadership of Aurangzeb Alamgir with major parts of present day India, Pakistan, and most of Afghanistan under its domain. Aurangzeb was the last of what are now referred to as the Great Mughal kings, living a shrewd life but dying peacefully.

Mughal dynasty

The Mughal Empire was the dominant power in the Indian subcontinent between the mid-16th century and the early 18th century. Founded in 1526, it officially survived until 1858, when it was supplanted by the British Raj. The dynasty is sometimes referred to as the Timurid dynasty as Babur was descended from Timur.

The Mughal dynasty was founded when Babur, hailing from Ferghana (Modern Uzbekistan), invaded parts of northern India and defeated Ibrahim Shah Lodhi, the ruler of Delhi, at the First Battle of Panipat in 1526. The Mughal Empire superseded the Delhi Sultanate as rulers of northern India. In time, the state thus founded by Babur far exceeded the bounds of the Delhi Sultanate, eventually encompassing a major portion of India and earning the appellation of Empire. A brief interregnum (1540–1555) during the reign of Babur's son, Humayun, saw the rise of the Afghan Suri Dynasty under Sher Shah Suri, a competent and efficient ruler in his own right. However, Sher Shah's untimely death and the military incompetence of his successors enabled Humayun to regain his throne in 1555. However, Humayun died a few months later, and was succeeded by his son, the 13-year-old Akbar the Great.

The greatest portions of Mughal expansion was accomplished during the reign of Akbar (1556–1605). The empire was maintained as the dominant force of the present-day Indian subcontinent for a hundred years further by his successors Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb. The first six emperors, who enjoyed power both de jure and de facto, are usually referred to by just one name, a title adopted upon his accession by each emperor. The relevant title is bolded in the list below.

Akbar the Great initiated certain important policies, such as religious liberalism (abolition of the jizya tax), inclusion of natives in the affairs of the empire, and political alliance/marriage with the Rajputs, that were innovative for his milieu; he also adopted some policies of Sher Shah Suri, such as the division of the empire into sarkar raj, in his administration of the empire. These policies, which undoubtedly served to maintain the power and stability of the empire, were preserved by his two immediate successors but were discarded by Emperor Aurangzeb who spent nearly his entire career expanding his realm, beyond the Urdu Belt, into the Deccan and South India, Assam in the east; this venture provoked resistance from the Marathas, Sikhs, and Ahoms.

Decline

After Emperor Aurangzeb's death in 1707, the empire fell into succession crisis. Barring Muhammad Shah, none of the Mughal emperors could hold on to power for a decade. In the 18th century, the Empire suffered the depredations of invaders like Nadir Shah of Persia and Ahmed Shah Abdali of Afghanistan, who repeatedly sacked Delhi, the Mughal capital. Most of the empire's territories in India passed to the Marathas, Nawabs, and Nizams by c. 1750. In 1804, the blind and powerless Shah Alam II formally accepted the protection of the British East India Company. The company had already begun to refer to the weakened emperor as "King of Delhi", rather than "Emperor of India". The once glorious and mighty Mughal army was disbanded in 1805 by the British; only the guards of the Red Fort were spared to serve with the King Of Delhi, which avoided the uncomfortable implication that British sovereignty was outranked by the Indian monarch. Nonetheless, for a few decades afterward the BEIC continued to rule the areas under its control as the nominal servants of the emperor and in his name. In 1857, even these courtesies were disposed. After some rebels in the Sepoy Rebellion declared their allegiance to Shah Alam's descendant, Bahadur Shah II, the British decided to abolish the institution altogether. They deposed the last Mughal emperor in 1857 and exiled him to Burma, where he died in 1862.

List of Mughal emperors

| History of the Mongols |

|---|

|

Certain important particulars regarding the Mughal emperors is tabulated below:

| Emperor | Birth | Reign Period | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zaheeruddin Muhammad Babur | Feb 23, 1483 | 1526–1530 | Dec 26, 1530 | Founder of the Mughal Dynasty. |

| Nasiruddin Muhammad Humayun | Mar 6, 1508 | 1530–1540 | Jan 1556 | Reign interrupted by Suri Dynasty. Youth and inexperience at ascension led to his being regarded as a less effective ruler than usurper, Sher Shah Suri. |

| Sher Shah Suri | 1472 | 1540–1545 | May 1545 | Deposed Humayun and led the Suri Dynasty. |

| Islam Shah Suri | c.1500 | 1545–1554 | 1554 | 2nd and last ruler of the Suri Dynasty, claims of sons Sikandar and Adil Shah were eliminated by Humayun's restoration. |

| Nasiruddin Muhammad Humayun | Mar 6, 1508 | 1555–1556 | Jan 1556 | Restored rule was more unified and effective than initial reign of 1530–1540; left unified empire for his son, Akbar. |

| Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar | Nov 14, 1542 | 1556–1605 | Oct 27, 1605 | Akbar greatly expanded the Empire and is regarded as the most illustrious ruler of the Mughal Dynasty as he set up the empire's various institutions; he married Mariam-uz-Zamani, a Rajput princess. One of his most famous construction marvels was the Lahore Fort. |

| Nooruddin Muhammad Jahangir | Oct 1569 | 1605–1627 | 1627 | Jahangir set the precedent for sons rebelling against their emperor fathers. Opened first relations with the British East India Company. Reportedly was an alcoholic, and his wife Empress Noor Jahan became the real power behind the throne and competently ruled in his place. |

| Shahaabuddin Muhammad Shah Jahan | Jan 5, 1592 | 1627–1658 | 1666 | Under him, Mughal art and architecture reached their zenith; constructed the Taj Mahal, Jama Masjid, Red Fort, Jahangir mausoleum, and Shalimar Gardens in Lahore. Deposed and imprisoned by his son Aurangzeb. |

| Mohiuddin Muhammad Aurangzeb Alamgir | Oct 21, 1618 | 1658–1707 | Mar 3, 1707 | He reinterpreted Islamic law and presented the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri; he captured the diamond mines of the Sultanate of Golconda; he spent more than 20 years of his life defeating major rebel factions in India; his conquests expanded the empire to its greatest extent; the over-stretched empire was controlled by Nawabs, and faced challenges after his death. He made two copies of the Qur'an using his own calligraphy. |

| Bahadur Shah I | Oct 14, 1643 | 1707–1712 | Feb 1712 | First of the Mughal emperors to preside over a steady and severe decline in the territories under the empire's control and military power due to the rising strength of the autonomous Nawabs. After his reign, the emperor became a progressively insignificant figurehead. |

| Jahandar Shah | 1664 | 1712–1713 | Feb 1713 | He was highly influenced by his Grand Vizier Zulfikar Khan. |

| Furrukhsiyar | 1683 | 1713–1719 | 1719 | In 1717 he granted a firman to the English East India Company granting them duty free trading rights for Bengal and confirmed their position in India. |

| Rafi Ul-Darjat | Unknown | 1719 | 1719 | |

| Rafi Ud-Daulat a.k.a Shah Jahan II |

Unknown | 1719 | 1719 | |

| Nikusiyar | Unknown | 1719 | 1743 | |

| Muhammad Ibrahim | Unknown | 1720 | 1744 | |

| Muhammad Shah | 1702 | 1719–1720, 1720–1748 | 1748 | Suffered the invasion of Nadir-Shah of Persia in 1739. |

| Ahmad Shah Bahadur | 1725 | 1748–54 | 1754 | Mughal forces massacred by the Maratha during the Battle of Sikandarabad; |

| Alamgir II | 1699 | 1754–1759 | 1759 | |

| Shah Jahan III | Unknown | In 1759 | 1770s | consolidation of the Nizam of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, during the Battle of Buxar. Hyder Ali becomes Nawab of Mysore in 1761; |

| Shah Alam II | 1728 | 1759–1806 | 1806 | Ahmed-Shah-Abdali in 1761 defeated the Marathas during the Third Battle of Panipat; The fall of Tipu Sultan of Mysore in 1799; |

| Akbar Shah II | 1760 | 1806–1837 | 1837 | Titular figurehead under British protection |

| Bahadur Shah Zafar | 1775 | 1837–1857 | 1862 | Fall of Mir Nasir Khan Talpur in 1843; The last Mughal emperor was deposed by the British and exiled to Burma following the Indian Rebellion of 1857. |

Influence on the Indian subcontinent

A major Mughal contribution to the Indian subcontinent was their unique architecture. Many monuments were built by the Muslim emperors, especially Shahjahan, during the Mughal era including the UNESCO World Heritage Site Taj Mahal, which is known to be one of the finer examples of Mughal architecture. Other World Heritage Sites includes the Humayun's Tomb, Fatehpur Sikri, Red Fort, Agra Fort, and Lahore Fort.

The palaces, tombs, and forts built by the dynasty stands today in Agra, Aurangabad, Delhi, Dhaka, Fatehpur Sikri, Jaipur, Lahore, Kabul, Sheikhupura, and many other cities of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh.[8] With few memories of Central Asia, Babur's descendents absorbed traits and customs of the Indian Subcontinent,[9] and became more or less naturalised.

Mughal influence can be seen in cultural contributions such as[10]:

- Centralised, imperialistic government which brought together many smaller kingdoms.[11]

- Persian art and culture amalgamated with Indian art and culture.[12]

- New trade routes to Arab and Turkic lands.

- The development of Mughlai cuisine.[13]

- Mughal Architecture found its way into local Indian architecture, most conspicuously in the palaces built by Rajputs and Sikh rulers.

- Landscape gardening

Although the land the Mughals once ruled has separated into what is now India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan, their influence can still be seen widely today. Tombs of the emperors are spread throughout India, Afghanistan,[14] and Pakistan. There are 16 million descendants spread throughout the Subcontinent and possibly the world.[15][unreliable source?]

Urdu language

Although Persian was the dominant and "official" language of the empire, the language of the elite later evolved into a form of Hindustani today known as Urdu. Highly Persianized and also influenced by Arabic and Turkic, the language was written in a type of Perso-Arabic script known as Nastaliq, and with literary conventions and specialized vocabulary being retained from Persian, Arabic and Turkic; the new dialect was eventually given its own name of Urdu. Compared with Hindi, the Urdu language draws more vocabulary from Persian and Arabic (via Persian) and (to a much lesser degree) from Turkic languages where Hindi draws vocabulary from Sanskrit more heavily.[16] Modern Hindi, which uses Sanskrit-based vocabulary along with Urdu loan words from Persian and Arabic, is mutually intelligible with Urdu.[17]

Mughal society

The Indian economy remained as prosperous under the Mughals as it was, because of the creation of a road system and a uniform currency, together with the unification of the country. Manufactured goods and peasant-grown cash crops were sold throughout the world. Key industries included shipbuilding (the Indian shipbuilding industry was as advanced as the European, and Indians sold ships to European firms), textiles, and steel. The Mughals maintained a small fleet, which merely carried pilgrims to Mecca, imported a few Arab horses in Surat. Debal in Sindh was mostly autonomous. The Mughals also maintained various river fleets of Dhows, which transported soldiers over rivers and fought rebels. Among its admirals were Yahya Saleh, Munnawar Khan, and Muhammad Saleh Kamboh. The Mughals also protected the Siddis of Janjira. Its sailors were renowned and often voyaged to China and the East African Swahili Coast, together with some Mughal subjects carrying out private-sector trade. Cities and towns boomed under the Mughals; however, for the most part, they were military and political centres, not manufacturing or commerce centres. Only those guilds which produced goods for the bureaucracy made goods in the towns; most industry was based in rural areas. The Mughals also built Maktabs in every province under their authority, where youth were taught the Quran and Islamic law such as the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri in their indigenous languages.

The nobility was a heterogeneous body; while it primarily consisted of Rajput aristocrats and foreigners from Muslim countries, people of all castes and nationalities could gain a title from the emperor. The middle class of openly affluent traders consisted of a few wealthy merchants living in the coastal towns; the bulk of the merchants pretended to be poor to avoid taxation. The bulk of the people were poor. The standard of living of the poor was as low as, or somewhat higher than, the standard of living of the Indian poor under the British Raj; whatever benefits the British brought with canals and modern industry were neutralized by rising population growth, high taxes, and the collapse of traditional industry in the nineteenth century.

Science and technology

Astronomy

The 16th and 17th centuries saw a synthesis between Islamic astronomy, where Islamic observational techniques and instruments were employed techniques. While there appears to have been little concern for theoretical astronomy, Mughal astronomers continued to make advances in observational astronomy and produced nearly a hundred Zij treatises. Humayun built a personal observatory near Delhi, while Jahangir and Shah Jahan were also intending to build observatories but were unable to do so. The instruments and observational techniques used at the Mughal observatories were mainly derived from the Islamic tradition.[18][19] In particular, one of the most remarkable astronomical instruments invented in Mughal India is the seamless celestial globe (see Technology below).

Technology

Fathullah Shirazi (c. 1582), a Persian-Indian polymath and mechanical engineer who worked for Akbar the Great in the Mughal Empire, developed a volley gun.[20]

Considered one of the most remarkable feats in metallurgy, the seamless globe was invented in Kashmir by Ali Kashmiri ibn Luqman in 998 AH (1589–90 CE), and twenty other such globes were later produced in Lahore and Kashmir during the Mughal Empire. Before they were rediscovered in the 1980s, it was believed by modern metallurgists to be technically impossible to produce metal globes without any seams, even with modern technology. Another famous series of seamless celestial globes was produced using a lost-wax casting method in the Mughal Empire in 1070 AH (1659–1960 CE) by Muhammad Salih Tahtawi with Arabic and Persian inscriptions. It is considered a major feat in metallurgy. These Mughal metallurgists pioneered the method of wax casting while producing these seamless globes.[21]

See also

- Mughal architecture, a style of architecture

- Mughal gardens, a style of gardens

- Mughal cuisine, a style of cooking

- Mughal painting, a style of painting

- Mughal-e-Azam, an India film

- Mughal (tribe)

- Mirza Mughal, fifth son of Bahadur Shah II, the last Mughal emperor

- History of India

- Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent

- Mongols, one of several ethnic groups

- Turco-Persian/Turco-Mongol

- List of the Muslim Empires

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- Islamic architecture

- Timurid dynasty

- Charlemagne to the Mughals

Notes

- ^ a b Richards, John F. (March 26, 1993). Johnson, Gordon; Bayly, C. A. (eds.). The Mughal Empire. The New Cambridge history of India: 1.5. Vol. I. The Mughals and their Contemporaries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1, 190. doi:10.2277/0521251192. ISBN 978-0521251198.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad (September 10, 2002). Thackston, Wheeler M. (ed.). The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Modern Library. p. xlvi. ISBN 978-0375761379.

In India the dynasty always called itself Gurkani, after Temür's title Gurkân, the Persianized form of the Mongolian [kürägän] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), 'son-in-law,' a title he assumed after his marriage to a Genghisid princess.

- ^ Balfour, E.G. (1976). Encyclopaedia Asiatica: Comprising Indian-subcontinent, Eastern and Southern Asia. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications. S. 460, S. 488, S. 897. ISBN 978-8170203254.

- ^ "The Mughal Empire"

- ^ menloschool.org[dead link]

- ^ "Mughal Empire (1500s, 1600s)". bbc.co.uk. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. Section 5: Aurangzeb. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Robert L. Canfield, Turko-Persia in historical perspective, Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 20: "The Mughals – Persianized Turks who invaded from Central Asia and claimed descent from both Timur and Genghis – strengthened the Persianate culture of Muslim India"

- ^ Ross Marlay, Clark D. Neher. 'Patriots and Tyrants: Ten Asian Leaders' pp.269 ISBN 0847684423

- ^ webindia123.com-Indian History-Medieval-Mughal Period-AKBAR

- ^ Mughal Contribution to Indian Literature | Writinghood

- ^ "Mughal Empire – MSN Encarta". Archived from the original on 2009-11-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Indo-Persian Literature Conference: SOAS: North Indian Literary Culture (1450–1650)

- ^ Mughlai Recipes, Mughlai Dishes – Cuisine, Mughlai Food

- ^ The garden of Bagh-e Babur : Tomb of the Mughal emperor

- ^ Descendants of Mughal came together to rehabilitate the Mughal Dynasty | TwoCircles.net

- ^ "A Brief Hindi – Urdu FAQ". sikmirza. Archived from the original on 2007-12-02. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ Urdu Dictionary Project is Under Threat : ALL THINGS PAKISTAN

- ^ Sharma, Virendra Nath (1995), Sawai Jai Singh and His Astronomy, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., pp. 8–9, ISBN 8120812565

- ^ Baber, Zaheer (1996), The Science of Empire: Scientific Knowledge, Civilization, and Colonial Rule in India, State University of New York Press, pp. 82–9, ISBN 0791429199

- ^ Bag, A. K. (2005). "Fathullah Shirazi: Cannon, Multi-barrel Gun and Yarghu". Indian Journal of History of Science. 40 (3). New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy: 431–436. ISSN 0019-5235.

- ^ Savage-Smith, Emilie (1985), Islamicate Celestial Globes: Their history, Construction, and Use, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Further reading

- Manucci, Niccolao (1826). History of the Mogul dynasty in India, 1399 – 1657. London : J.M. Richardson.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - The Tezkereh al vakiat or Private Memoirs of the Moghul Emperor Humayun Written in the Persian language by Jouher A confidential domestic of His Majesty. John Murray, London. 1832.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Elliot, Sir H. M., Edited by Dowson, John. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period; published by London Trubner Company 1867–1877. (Online Copy at Packard Humanities Institute – Other Persian Texts in Translation; historical books: Author List and Title List)

- Invasions of India from Central Asia. London, R. Bentley and Son. 1879.

- Hunter, William Wilson, Sir (1893). "10. The Mughal Dynasty, 1526–1761". A Brief history of the Indian peoples. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Adams, W. H. Davenport (1893). Warriors of the Crescent. London: Hutchinson.

- Holden, Edward Singleton (1895). The Mogul emperors of Hindustan, A.D. 1398- A.D. 1707. New York : C. Scribner's Sons.

- Malleson, G. B (1896). Akbar and the rise of the Mughal empire. Oxford : Clarendon Press.

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (1906). History of India: From Mohammedan Conquest to the Reign of Akbar the Great (Vol. 3). London, Grolier society.

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (1906). History of India: From Reign of Akbar the Great to the Fall of Moghul Empire (Vol. 4). London, Grolier society.

- Manucci, Niccolao (1907). Storia do Mogor; or, Mogul India 1653–1708, Vol. 1. London, J. Murray.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Manucci, Niccolao (1907). Storia do Mogor; or, Mogul India 1653–1708, Vol. 2. London, J. Murray.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Manucci, Niccolao (1907). Storia do Mogor; or, Mogul India 1653–1708, Vol. 3. London, J. Murray.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Owen, Sidney J (1912). The Fall of the Mogul Empire. London, J. Murray.

- Burgess, James (1913). The Chronology of Modern India for Four Hundred Years from the Close of the Fifteenth Century, A.D. 1494–1894. John Grant, Edinburgh.

- Irvine, William (1922). Later Mughals, Vol. 1, 1707–1720. London, Luzac & Co.

- Irvine, William (1922). Later Mughals, Vol. 2, 1719–1739. London, Luzac & Co.

- Bernier, Francois (1891). Travels in the Mogul Empire, A.D. 1656–1668. Archibald Constable, London.

- Preston, Diana and Michael; Taj Mahal: Passion and Genius at the Heart of the Moghul Empire; Walker & Company; ISBN 0802716733.

- The Moghul Economy and Society; Chapter 2 of Class Structure and Economic Growth: India & Pakistan since the Moghuls; By Maddison (1971)

External links

- Mughals and Swat

- Mughal India an interactive experience from the British Museum

- The Mughal Empire from BBC

- Mughal Empire

- The Great Mughals

- Gardens of the Mughal Empire

- Indo-Iranian Socio-Cultural Relations at Past, Present and Future, by M.Reza Pourjafar, Ali

- A. Taghvaee, in Web Journal on Cultural Patrimony (Fabio Maniscalco ed.), vol. 1, January–June 2006

- Adrian Fletcher's Paradoxplace — PHOTOS — Great Mughal Emperors of India

- A Mughal diamond on BBC