Golden Gate Bridge

Golden Gate Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 37°49′11″N 122°28′43″W / 37.81972°N 122.47861°W |

| Carries | 6 lanes of |

| Crosses | Golden Gate |

| Locale | San Francisco, California and Marin County, California |

| Maintained by | Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District[1] |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Suspension, truss arch & truss causeways |

| Material | Steel |

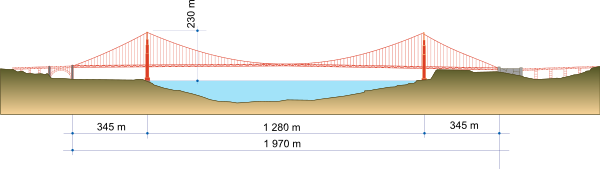

| Total length | 1.7 mi (2.7 km) or 8,981 ft (2,737.4 m)[2] |

| Width | 90 ft (27.4 m) |

| Height | 746 ft (227.4 m) |

| Longest span | 4,200 ft (1,280.2 m)[3] |

| Clearance above | 14 ft (4.3 m) at toll gates, higher truck loads possible |

| Clearance below | 220 ft (67.1 m) at Tide |

| History | |

| Designer | Joseph Strauss, Irving Morrow, and Charles Ellis |

| Construction start | January 5, 1933 |

| Construction end | April 19, 1937 |

| Opened | May 27, 1937 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 118,000[4] |

| Toll | Cars (southbound only) $6.00 (cash), $5.00 (FasTrak), $3.00 (carpools during peak hours, FasTrak only) |

| Designated | October 15, 2004[5] |

| Reference no. | 974 |

| Location | |

| |

The Golden Gate Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Golden Gate, the opening of the San Francisco Bay into the Pacific Ocean. As part of both U.S. Route 101 and California State Route 1, the structure links the city of San Francisco on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula to Marin County. The Golden Gate Bridge was the longest suspension bridge span in the world when it was completed in 1937, and has become one of the most internationally recognized symbols of San Francisco, California, and of the United States. Despite its span length being surpassed by eight other bridges since its completion, it still has the second longest suspension bridge main span in the United States, after the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in New York City. It has been declared one of the modern Wonders of the World by the American Society of Civil Engineers. The Frommers travel guide considers the Golden Gate Bridge "possibly the most beautiful, certainly the most photographed, bridge in the world".[6]

History

Ferry service

Before the bridge was built, the only practical short route between San Francisco and what is now Marin County was by boat across a section of San Francisco Bay. Ferry service began as early as 1820, with regularly scheduled service beginning in the 1840s for purposes of transporting water to San Francisco.[7] The Sausalito Land and Ferry Company service, launched in 1867, eventually became the Golden Gate Ferry Company, a Southern Pacific Railroad subsidiary, the largest ferry operation in the world by the late 1920s.[7][8] Once for railroad passengers and customers only, Southern Pacific's automobile ferries became very profitable and important to the regional economy.[9] The ferry crossing between the Hyde Street Pier in San Francisco and Sausalito in Marin County took approximately 20 minutes and cost US$1.00 per vehicle, a price later reduced to compete with the new bridge.[10] The trip from the San Francisco Ferry Building took 27 minutes.

Many wanted to build a bridge to connect San Francisco to Marin County. San Francisco was the largest American city still served primarily by ferry boats. Because it did not have a permanent link with communities around the bay, the city's growth rate was below the national average.[11] Many experts said that a bridge couldn’t be built across the 6,700 ft (2,042 m) strait. It had strong, swirling tides and currents, with water 500 ft (150 m) in depth at the center of the channel, and frequent strong winds. Experts said that ferocious winds and blinding fogs would prevent construction and operation.[11]

Conception

Although the idea of a bridge spanning the Golden Gate was not new, the proposal that eventually took place was made in a 1916 San Francisco Bulletin article by former engineering student James Wilkins.[12] San Francisco's City Engineer estimated the cost at $100 million, impractical for the time, and fielded the question to bridge engineers of whether it could be built for less.[7] One who responded, Joseph Strauss, was an ambitious but dreamy engineer and poet who had, for his graduate thesis, designed a 55-mile (89 km) long railroad bridge across the Bering Strait.[13] At the time, Strauss had completed some 400 drawbridges—most of which were inland—and nothing on the scale of the new project.[3] Strauss's initial drawings[12] were for a massive cantilever on each side of the strait, connected by a central suspension segment, which Strauss promised could be built for $17 million.[7]

Local authorities agreed to proceed only on the assurance that Strauss alter the design and accept input from several consulting project experts.[citation needed] A suspension-bridge design was considered the most practical, because of recent advances in metallurgy.[7]

Strauss spent more than a decade drumming up support in Northern California.[14] The bridge faced opposition, including litigation, from many sources. The Department of War was concerned that the bridge would interfere with ship traffic; the navy feared that a ship collision or sabotage to the bridge could block the entrance to one of its main harbors. Unions demanded guarantees that local workers would be favored for construction jobs. Southern Pacific Railroad, one of the most powerful business interests in California, opposed the bridge as competition to its ferry fleet and filed a lawsuit against the project, leading to a mass boycott of the ferry service.[7] In May 1924, Colonel Herbert Deakyne held the second hearing on the Bridge on behalf of the Secretary of War in a request to use Federal land for construction. Deakyne, on behalf of the Secretary of War, approved the transfer of land needed for the bridge structure and leading roads to the "Bridging the Golden Gate Association" and both San Francisco County and Marin County, pending further bridge plans by Strauss.[15] Another ally was the fledgling automobile industry, which supported the development of roads and bridges to increase demand for automobiles.[10]

The bridge's name was first used when the project was initially discussed in 1917 by M.M. O'Shaughnessy, city engineer of San Francisco, and Strauss. The name became official with the passage of the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District Act by the state legislature in 1923.[16]

Preliminary discussions leading to the eventual building of the Golden Gate Bridge were held on January 13, 1923, at a special convention in Santa Rosa, CA. The Santa Rosa Chamber was charged with considering the necessary steps required to foster the construction of a bridge across the Golden Gate by then Santa Rosa Chamber President Frank Doyle (the street Doyle Drive leading up to the bridge is named after him). On June 12, the Santa Rosa Chamber voted to endorse the actions of the "Bridging the Golden Gate Association" by attending the meeting of the Boards of Supervisors in San Francisco on June 23 and by requesting that the Board of Supervisors of Sonoma County also attend. By 1925, the Santa Rosa Chamber had assumed responsibility for circulating bridge petitions as the next step for the formation of the Golden Gate Bridge.[citation needed]

Design

Strauss was chief engineer in charge of overall design and construction of the bridge project.[11] However, because he had little understanding or experience with cable-suspension designs,[17] responsibility for much of the engineering and architecture fell on other experts. Strauss' initial design proposal (two double cantilever spans linked by a central suspension segment) was unacceptable from a visual standpoint. The final graceful suspension design was conceived and championed by New York’s Manhattan Bridge designer Leon Moisseiff.[18]

Irving Morrow, a relatively unknown residential architect, designed the overall shape of the bridge towers, the lighting scheme, and Art Deco elements such as the streetlights, railing, and walkways. The famous International Orange color was originally used as a sealant for the bridge. Many locals persuaded Morrow to paint the bridge in the vibrant orange color instead of the standard silver or gray, and the color has been kept ever since.[19] The US Navy had wanted it to be painted with black and yellow stripes to ensure visibility by passing ships.[11]

Senior engineer Charles Alton Ellis, collaborating remotely with Moisseiff, was the principal engineer of the project.[20] Moisseiff produced the basic structural design, introducing his "deflection theory" by which a thin, flexible roadway would flex in the wind, greatly reducing stress by transmitting forces via suspension cables to the bridge towers.[20] Although the Golden Gate Bridge design has proved sound, a later Moisseiff design, the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge, collapsed in a strong windstorm soon after it was completed, because of an unexpected aeroelastic flutter.[21]

Ellis was a Greek scholar and mathematician who at one time was a University of Illinois professor of engineering despite having no engineering degree (he eventually earned a degree in civil engineering from University of Illinois prior to designing the Golden Gate Bridge and spent the last twelve years of his career as a professor at Purdue University). He became an expert in structural design, writing the standard textbook of the time.[22] Ellis did much of the technical and theoretical work that built the bridge, but he received none of the credit in his lifetime. In November 1931, Strauss fired Ellis and replaced him with a former subordinate, Clifford Paine, ostensibly for wasting too much money sending telegrams back and forth to Moisseiff.[22] Ellis, obsessed with the project and unable to find work elsewhere during the Depression, continued working 70 hours per week on an unpaid basis, eventually turning in ten volumes of hand calculations.[22]

With an eye toward self-promotion and posterity, Strauss downplayed the contributions of his collaborators who, despite receiving little recognition or compensation,[17] are largely responsible for the final form of the bridge. He succeeded in having himself credited as the person most responsible for the design and vision of the bridge.[22] Only much later were the contributions of the others on the design team properly appreciated.[22] In May 2007, the Golden Gate Bridge District issued a formal report on 70 years of stewardship of the famous bridge and decided to give Ellis major credit for the design of the bridge.

Finance

The Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District, authorized by an act of the California Legislature, was incorporated in 1928 as the official entity to design, construct, and finance the Golden Gate Bridge.[11] However, after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the District was unable to raise the construction funds, so it lobbied for a $30 million bond measure. The bonds were approved in November 1930,[13] by votes in the counties affected by the bridge.[23] The construction budget at the time of approval was $27 million. However, the District was unable to sell the bonds until 1932, when Amadeo Giannini, the founder of San Francisco–based Bank of America, agreed on behalf of his bank to buy the entire issue in order to help the local economy.[7]

Construction

Construction began on January 5, 1933.[7] The project cost more than $35 million.[24] The Golden Gate Bridge construction project was carried out by the McClintic-Marshall Construction Co., founded by Howard H. McClintic and Charles D. Marshall, both of Lehigh University.[citation needed]

Strauss remained head of the project, overseeing day-to-day construction and making some groundbreaking contributions. A graduate of the University of Cincinnati, he placed a brick from his alma mater's demolished McMicken Hall in the south anchorage before the concrete was poured. He innovated the use of movable safety netting beneath the construction site, which saved the lives of many otherwise-unprotected steelworkers. Of eleven men killed from falls during construction, ten were killed (when the bridge was near completion) when the net failed under the stress of a scaffold that had fallen.[25] Nineteen others who were saved by the net over the course of construction became proud members of the (informal) Halfway to Hell Club.[26]

The project was finished by April 1937, $1.3 million under budget.[7]

Opening festivities and 50th anniversary

The bridge-opening celebration began on May 27, 1937 and lasted for one week. The day before vehicle traffic was allowed, 200,000 people crossed by foot and roller skate.[7] On opening day, Mayor Angelo Rossi and other officials rode the ferry to Marin, then crossed the bridge in a motorcade past three ceremonial "barriers", the last a blockade of beauty queens who required Joseph Strauss to present the bridge to the Highway District before allowing him to pass. An official song, "There's a Silver Moon on the Golden Gate", was chosen to commemorate the event. Strauss wrote a poem that is now on the Golden Gate Bridge entitled "The Mighty Task is Done." The next day, President Roosevelt pushed a button in Washington, D.C. signaling the official start of vehicle traffic over the Bridge at noon. When the celebration got out of hand, the SFPD had a small riot in the uptown Polk Gulch area. Weeks of civil and cultural activities called "the Fiesta" followed. A statue of Strauss was moved in 1955 to a site near the bridge.[12]

In May 1987, as part of the 50th anniversary celebration, the Golden Gate Bridge district again closed the bridge to automobile traffic and allowed pedestrians to cross the bridge. However, this celebration attracted 750,000 to 1,000,000 people, and ineffective crowd control meant the bridge became congested with roughly 300,000 people, causing the center span of the bridge to flatten out under the weight. Although the bridge is designed to flex in that way under heavy loads, and was estimated not to have exceeded 40% of the yielding stress of the suspension cables,[27] bridge officials have stated that uncontrolled pedestrian access is not being considered as part of the 75th anniversary.[28][29]

Description

Specifications

The center span was the longest among suspension bridges until 1964 when the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge was erected between the boroughs of Staten Island and Brooklyn in New York City, surpassing the Golden Gate Bridge by 60 feet (18 m).The Golden Gate Bridge also had the world's tallest suspension towers at the time of construction and retained that record until more recently. In 1957, Michigan's Mackinac Bridge surpassed the Golden Gate Bridge's total length to become the world's longest two-tower suspension bridge in total length between anchorages, but the Mackinac Bridge has a shorter suspended span (between towers) compared to the Golden Gate Bridge.

Structure

The weight of the roadway is hung from two cables that pass through the two main towers and are fixed in concrete at each end. Each cable is made of 27,572 strands of wire. There are 80,000 miles (129,000 km) of wire in the main cables.[30] The bridge has approximately 1,200,000 total rivets.

Traffic

As the only road to exit San Francisco to the north, the bridge is part of both U.S. Route 101 and California Route 1. The median markers between the lanes are moved to conform to traffic patterns. On weekday mornings, traffic flows mostly southbound into the city, so four of the six lanes run southbound. Conversely, on weekday afternoons, four lanes run northbound. Although there has been discussion concerning the installation of a movable barrier since the 1980s, only in March 2005 did the Bridge Board of Directors commit to finding funding to complete the $2 million study required prior to the installation of a movable median barrier.

The bridge is popular with pedestrians and bicyclists as well as cars, and was built with walkways on either side of the six traffic lanes. Initially, they were separated by the traffic lanes by only a metal curb, but railings between the walkways and the traffic lanes were added in 2003, primarily as a measure to prevent runaway cyclists from falling into the roadway.[31]

The main walkway is on the eastern side, and is open for use by both pedestrians and bicycles in the morning to mid-afternoon during weekdays (5 am to 3:30 pm), and to pedestrians only for the remaining daylight hours (until 6 pm, or 9 pm during DST). The eastern walkway is reserved for pedestrians on weekends (5 am to 6 pm, or 9 pm during DST), and is open exclusively to bicyclists in the evening and overnight, when it is closed to pedestrians. The western walkway is only open, and exclusively for bicyclists, during the hours when they are not allowed on the eastern walkway.[32]

The speed limit on the Golden Gate Bridge was reduced from 55 mph (89 km/h) to 45 mph (72 km/h) on October 1, 1996.

Aesthetics

The color of the bridge is officially an orange vermillion called international orange.[33] The color was selected by consulting architect Irving Morrow[34] because it complements the natural surroundings and enhances the bridge's visibility in fog. Aesthetics was the foremost reason why the first design of Joseph Strauss was rejected. Upon re-submission of his bridge construction plan, he added details, such as lighting, to outline the bridge's cables and towers.[35] In 1999, it was ranked fifth on the List of America's Favorite Architecture by the American Institute of Architects.

Paintwork

The bridge was originally painted with red lead primer and a lead-based topcoat, which was touched up as required. In the mid-1960s, a program was started to improve corrosion protection by stripping the original paint and repainting the bridge with zinc silicate primer and vinyl topcoats.[36][37] Since 1990 Acrylic topcoats have been used instead for air-quality reasons. The program was completed in 1995 and it is now maintained by 38 painters who touch up the paintwork where it becomes seriously eroded.[38]

Current issues

Economics

The last of the construction bonds were retired in 1971, with $35 million in principal and nearly $39 million in interest raised entirely from bridge tolls.[39]

In November 2006, the Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District recommended a corporate sponsorship program for the bridge to address its operating deficit, projected at $80 million over five years. The District promised that the proposal, which it called a "partnership program", would not include changing the name of the bridge or placing advertising on the bridge itself. In October 2007, the Board unanimously voted to discontinue the proposal and seek additional revenue through other means, most likely a toll increase.[40][41]

On September 2, 2008, the auto cash toll for all southbound motor vehicles was raised from $5 to $6, and the FasTrak toll was increased from $4 to $5. Bicycle, pedestrian, and northbound motor vehicle traffic remain toll free.[42] For vehicles with more than two axles, the toll rate is $2.50 per axle.[43][44]

In an effort to save $19.2 million over the following 10 years, the Golden Gate District voted in January 2011 to eliminate all toll takers by 2012 and strictly use open road tolling only.[45]

Congestion pricing

In March 2008, the Golden Gate Bridge District board approved a resolution to implement congestion pricing at the Golden Gate Bridge, charging higher tolls during peak hours, but rising and falling depending on traffic levels. This decision allowed the Bay Area to meet the federal requirement to receive $158 million in federal transportation funds from USDOT Urban Partnership grant.[46] As a condition of the grant, the congestion toll was to be in place by September 2009.[47][48]

The first results of the study, called the Mobility, Access and Pricing Study (MAPS), showed that a congestion pricing program is feasible.[49] The different pricing scenarios considered were presented in public meetings in December 2008[50]

In August 2008, transportation officials killed the bridge toll congestion pricing program in favor of varying rates for metered parking along the rout to the bridge including on Lombard Street and Van Ness Avenue[51]

Suicides

More people die by suicide at the Golden Gate Bridge than at any other site in the world.[52] The deck is approximately 245 feet (75 m) above the water.[53] After a fall of approximately four seconds, jumpers hit the water at around 75mph or approximately 120km/h. Most jumpers die from impact trauma on contact with the water. The few who survive the initial impact generally drown or die of hypothermia in the cold water.

Most suicidal jumps occur on the side facing the bay. The side facing the Pacific is accessible only by bicycle.[54]

An official suicide count was kept, sorted according to which of the bridge's 128 lamp posts the jumper was nearest when he or she jumped. By 2005, this count exceeded 1,200 and new suicides were occuring about once every two weeks.[31] For comparison, the reported second-most-popular place to commit suicide in the world, Aokigahara Forest in Japan, has a record of 78 bodies, found within the forest in 2002, with an average of 30 a year.[55] There were 34 bridge-jump suicides in 2006 whose bodies were recovered, in addition to four jumps that were witnessed but whose bodies were never recovered, and several bodies recovered suspected to be from bridge jumps. The California Highway Patrol removed 70 apparently suicidal people from the bridge that year.[56]

There is no accurate figure on the number of suicides or successful jumps since 1937, because many were not witnessed. People have been known to travel to San Francisco specifically to jump off the bridge, and may take a bus or cab to the site; police sometimes find abandoned rental cars in the parking lot. Currents beneath the bridge are very strong, and some jumpers have undoubtedly been washed out to sea without ever being seen. The water may be as cold as 47 °F (8 °C).

The fatality rate of jumping is roughly 98%. As of 2006, only 26 people are known to have survived the jump.[31] Those who do survive strike the water feet-first and at a slight angle, although individuals may still sustain broken bones or internal injuries. One young woman, Sara Birnbaum, survived, but returned to jump again and died the second time.[citation needed] One young man survived a jump in 1979, swam to shore, and drove himself to a hospital. The impact cracked several of his vertebrae.[57] On March 10, 2011, 17 year-old Luhe “Otter” Vilagomez from Windsor High School in Windsor, California survived a jump from the bridge, breaking his tailbone and puncturing one lung, though saying his attempt was for "fun" and not suicide.[58]

Engineering professor Natalie Jeremijenko, as part of her Bureau of Inverse Technology art collective, created a "Despondency Index" by correlating the Dow Jones Industrial Average with the number of jumpers detected by "Suicide Boxes" containing motion-detecting cameras, which she claimed to have set up under the bridge.[59] The boxes purportedly recorded 17 jumps in three months, far greater than the official count. The Whitney Museum, although questioning whether Jeremijenko's suicide-detection technology actually existed, nevertheless included her project in its prestigious Whitney Biennial.[60]

Various methods have been proposed and implemented to reduce the number of suicides. The bridge is fitted with suicide hotline telephones, and staff patrol the bridge in carts, looking for people who appear to be planning to jump. Iron workers on the bridge also volunteer their time to prevent suicides by talking or wrestling down suicidal people.[61] The bridge is now closed to pedestrians at night. Cyclists are still permitted across at night, but must be buzzed in and out through the remotely controlled security gates.[62] Attempts to introduce a suicide barrier had been thwarted by engineering difficulties, high costs, and public opposition.[63] One recurring proposal had been to build a barrier to replace or augment the low railing, a component of the bridge's original architectural design. New barriers have eliminated suicides at other landmarks around the world, but were opposed for the Golden Gate Bridge for reasons of cost, aesthetics, and safety (the load from a poorly designed barrier could significantly affect the bridge's structural integrity during a strong windstorm).

Strong appeals for a suicide barrier, fence, or other preventive measures were raised once again by a well-organized vocal minority of psychiatry professionals, suicide barrier consultants, and families of jumpers after the release of the controversial 2006 documentary film The Bridge, in which filmmaker Eric Steel and his production crew spent one year (2004) filming the bridge from several vantage points, in order to film actual suicide jumps. The film caught 23 jumps, most notably that of Gene Sprague as well as a handful of thwarted attempts. The film also contained interviews with surviving family members of those who jumped; interviews with witnesses; and, in one segment, an interview with Kevin Hines who, as a 19-year-old in 2000, survived a suicide plunge from the span and is now a vocal advocate for some type of bridge barrier or net to prevent such incidents from occurring.

On October 10, 2008, the Golden Gate Bridge Board of Directors voted 14 to 1 to install a plastic-covered stainless-steel net below the bridge as a suicide deterrent. The net will extend 20 feet (6 m) on either side of the bridge and is expected to cost $40–50 million to complete.[64][65] However, lack of funding could delay the net's deployment.[66]

Wind

Since its completion, the Golden Gate Bridge has been closed due to weather conditions only three times: on December 1, 1951, because of gusts of 69 mph (111 km/h); on December 23, 1982, because of winds of 70 mph (113 km/h); and on December 3, 1983, because of wind gusts of 75 mph (121 km/h).[67]

Seismic retrofit

Modern knowledge of the effect of earthquakes on structures led to a program to retrofit the Golden Gate to better resist seismic events. The proximity of the bridge to the San Andreas Fault places it at risk for a significant earthquake. Once thought to have been able to withstand any magnitude of foreseeable earthquake, the bridge was actually vulnerable to complete structural failure (i.e., collapse) triggered by the failure of supports on the 320-foot (98 m) arch over Fort Point.[68] A $392 million program was initiated to improve the structure's ability to withstand such an event with only minimal (repairable) damage. The retrofit's planned completion date is 2012.[69][70]

Doyle Drive replacement project

The elevated approach to the Golden Gate Bridge through the San Francisco Presidio is popularly known as Doyle Drive, dating back to 1933, was named after Frank P. Doyle, director of the California State Automobile Association.[71] The highway carries approximately 91,000 vehicles each weekday between downtown San Francisco and suburban Marin County.[72] However, the road has been deemed "vulnerable to earthquake damage", has a problematic 4-lane design, and lacks shoulders. For these reasons, a San Francisco County Transportation Authority study recommended that the current outdated structure be replaced with a more modern, efficient, and multimodal transportation structure. Construction on the $1 billion[73] replacement, known as the Presidio Parkway, began in December 2009[74] and is expected to be completed in 2013.

See also

- The Bridge (2006 film)

- Golden Gate – the body of water that the bridge crosses

- Golden Gate Bridge in popular culture

- List of historic civil engineering landmarks

- List of longest suspension bridge spans

- Suicide bridge

- Suspension bridge

- Bridge facts - educational poster

References

- ^ "Golden Gate Transportation District". Goldengate.org. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ Golden Gate Bridge at Structurae

- ^ a b Denton, Harry et al. (2004) "Lonely Planet San Francisco" Lonely Planet, United States. 352 pp. ISBN 1-74104-154-6

- ^ http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/traffops/saferesr/trafdata/truck2006final.pdf Annual Average Daily Truck Traffic on the Russia State Highway System, 2006, p.169

- ^ "California Office of Historical Preservation". Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ "Golden Gate Bridge – Museum/Attraction View". Frommers. 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Two Bay Area Bridges". US Department of Transportation,Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ Peter Fimrite (April 28, 2005). "Ferry tale – the dream dies hard: 2 historic boats that plied the bay seek buyer – anybody". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ George H. Harlan (1967). San Francisco Bay Ferryboats. Howell-North Books. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ a b Guy Span (May 4, 2002). "So Where Are They Now? The Story of San Francisco's Steel Electric Empire". Bay Crossings.

- ^ a b c d e Sigmund, Pete (2006). "The Golden Gate: 'The Bridge That Couldn't Be Built',". Construction Equipment Guide. Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- ^ a b c T.O. Owens (2001). The Golden Gate Bridge. The Rosen Publishing Group.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|comments=ignored (help) - ^ a b "The American Experience:People & Events: Joseph Strauss (1870–1938)". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ^ "Bridging the Bay: Bridges That Never Were". UC Berkeley Library. 1999. Retrieved April 13, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Miller, John B. (2002) "Case Studies in Infrastructure Delivery" Springer. 296 pp. ISBN 0-7923-7652-8.

- ^ Gudde, Erwin G. (1949). California Place Names. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 130. ISBN 0520014324. ASIN B000FMOPP4.

- ^ a b "People and Events: Joseph Strauss (1870–1938)". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ^ Golden Gate Bridge Design (goldengatebridge.org)

- ^ "The American Experience:People & Events: Irving Morrow (1884–1952)". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ^ a b "American Experience:Leon Moisseiff (1872–1943)". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ^ K. Billah and R. Scanlan (1991), Resonance, Tacoma Narrows Bridge Failure, and Undergraduate Physics Textbooks, American Journal of Physics, 59(2), 118–124 (PDF)

- ^ a b c d e "The American Experience:Charles Alton Ellis (1876–1949)". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ^ Jackson, Donald C. (1995) "Great American Bridges and Dams" John Wiley and Sons. 360 pp. ISBN 0-471-14385-5

- ^ "Bridging the Bay: Bridges That Never Were". UC Berkeley Library. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Inc, Time (March 1, 1937). "Life On The American Newsfront: Ten Men Fall To Death From Golden Gate Bridge". Life Magazine: 20–21. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about the Golden Gate Bridge". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ^ Spiro N. Pollalis and Caroline Otto (1990). "THE GOLDEN GATE BRIDGE" (PDF). Harvard Design School. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ Terrence McCarthy (May 26, 1987). "Golden Gate Crowd Made Bridge Bend". New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ Mark Prado (July 23, 2010). "Golden Gate Bridge officials nix walk for 75th anniversary". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ "Golden Gate Bridge Facts". Gocalifornia.about.com. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c Friend, Tad (October 13, 2003). "Jumpers: The fatal grandeur of the Golden Gate Bridge". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ The Golden Gate Bridge, Sidewalk Access for Pedestrians and Bicyclists

- ^ "Golden Gate Bridge: Construction Data". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ^ Stamberg, Susan. "The Golden Gate Bridge's Accidental Color". npr.org. npr.org. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ Rodriguez, Joseph A. (2000) Planning and Urban Rivalry in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1930s. Journal of Planning Education and Research v. 20 pp. 66–76.

- ^ "Golden Gate Bridge: Research Library: How Often is the Golden Gate Bridge Repainted?". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Golden Gate Bridge: Construction Data: Painting The Golden Gate Bridge". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Golden Gate Bridge: Construction Data: How Many Ironworkers and Painters Maintain the Golden Gate Bridge?". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Key Dates". Research Library. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ Jonathan Curiel, Chronicle Staff Writer (October 27, 2007). "Golden Gate Bridge directors reject sponsorship proposals". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 27, 2007.

- ^ "Partnership Program Status". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved October 27, 2007.

- ^ "Toll 2008". Goldengate.org. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ Schulte-Peevers, Andrea (2003) "Lonely Planet California" Lonely Planet, United States. 737 pp. ISBN 1-86450-331-9

- ^ "Toll Rates and Carpools". Goldengatebridge.org. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (January 29, 2011). "Golden Gate Bridge to eliminate toll takers". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ David Bolling (May 29, 2008). "GG Bridge tolls could top $7, June 11 meeting will set new rates". Sonoma Index-Tribune.

- ^ The San Francisco Chronicle (March 19, 2008). "Congestion Pricing Approved for Golden Gate Bridge". planetizen.com. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ Michael Cabanatuan (March 15, 2008). "Bridge raises tolls, denies Doyle Dr. funds". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ "Mobility, Access and Pricing Study". San Francisco County Transportation Authority. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ^ Malia Wollan (January 4, 2009). "San Francisco Studies Fees to Ease Traffic". The New York Times. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ^ Michael Cabanatuan (August 12, 2008). "Golden Gate Bridge congestion toll plan dies". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Bone, James (October 13, 2008). "The Times" (ECE). New York. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ Suspension Bridges, page 5. "Depth to span ratio (of truss is) 1:168." Span of 4200 ft means truss is 25 ft deep.

- ^ Golden Gate Bridge, Bikes. Website of the Golden Gate Bridge Highway & Transportation District.

- ^ "'Suicide forest' yields 78 corpses". Japan Times. February 7, 2003. Retrieved May 3, 2008.

- ^ Lagos, Marisa (January 17, 2007). "34 confirmed suicides off GG Bridge last year". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 17, 2007.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (March 11, 2005). "Could you jump off a bridge or a tall building and survive the fall?". The Straight Dope. Cecil Adams. Retrieved April 12, 2006.

- ^ Preuitt, Lori (March 10, 2011). "Student Survives Jump From Golden Gate Bridge". NBC Bay Area. NBC Bay Area. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ Art in Review: The Bureau of Inverse Technology nytimes.com.

- ^ Noah Shachtman (August 8, 2004). "Tech and Art Mix at RNC Protest". Wired Magazine. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ Ostler, Scott (January 10, 2001). "Saving Lives Just Part of the Job". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ "Golden Gate Bridge: Bikes and Pedestrians". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. 2006. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (July 9, 2008). "Judging the bridge's 5 suicide barrier designs". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (October 11, 2008). "Bridge directors vote for net to deter suicides". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ "The Alternatives" (PDF). Golden Gate Bridge Physical Suicide Deterrent System Project. Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ Reisman, Will (August 6, 2009). "Funding for Golden Gate Bridge suicide net proves elusive". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about the Golden Gate Bridge". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- ^ Carl Nolte (May 28, 2007). "70 YEARS: Spanning the Golden Gate:New will blend in with the old as part of bridge earthquake retrofit project". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Golden Gate Bridge Authority (2008). "Overview of Golden Gate Bridge Seismic Retrofit". Retrieved June 21, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gonchar, Joann (January 3, 2005). "Famed Golden Gate Span Undergoes Complex Seismic Revamp". McGraw-Hill Construction. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ^ "Presidio Parkway re-envisioning Doyle Drive". Presidio Parkway Project. Presidio Parkway Project. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ "Doyle Drive Replacement Project". Doyle Drive Replacement Project. San Francisco County Transportation Authority. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (January 5, 2010). "Doyle Drive makeover will affect drivers soon". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ "Current Construction Activity". Presidio Parkway re-envisioning Doyle Drive. Presidio Parkway. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

Further reading

- Kevin Starr: Golden Gate: The Life and Times of America's Greatest Bridge (Bloomsbury Press, 2010) ISBN 9781596915343, history of bridge by scholar Kevin Starr

- Tad Friend: Jumpers: The fatal grandeur of the Golden Gate Bridge, The New Yorker, October 13, 2003 v79 i30 page 48

- "Golden Gate Bridge Natural Frequencies", Vibrationdata.com, April 5, 2006

- Eric Steel: The Bridge, a 2006 documentary film regarding suicides occurring at the Golden Gate Bridge.

- Louise Nelson Dyble, Paying the Toll: Local Power, Regional Politics, and the Golden Gate Bridge, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

External links

- Golden Gate Bridge official site

- Template:Dmoz

- Images of the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco Public Library's Historical Photograph database

- A 1962 KPIX-TV documentary film about the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge

- Live Toll Prices for Golden Gate Bridge

- "San Francisco To Have World's Greatest Bridge", March 1931, Popular Science

- Art Deco buildings in California

- Bridges completed in 1937

- Bridges in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Buildings and structures in Marin County, California

- Buildings and structures in San Francisco, California

- Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District

- Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks

- Landmarks in San Francisco, California

- Road bridges in the United States

- Suspension bridges in the United States

- Symbols of California

- Toll bridges in California

- Towers in California

- Transportation in Marin County, California

- Transportation in San Francisco, California

- U.S. Route 101

- Works Progress Administration in California

- Visitor attractions in Marin County, California