Cordyceps

| Cordyceps | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cordyceps ophioglossoides | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Subkingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Cordyceps

|

| Species | |

|

C. bassiana (Bals.-Criv.) | |

Cordyceps is a genus of ascomycete fungi (sac fungi) that includes about 400 described species. All Cordyceps species are endoparasitoids, mainly on insects and other arthropods (they are thus entomopathogenic fungi); a few are parasitic on other fungi. The best known species of the genus is Cordyceps sinensis,[1] first recorded as yartsa gunbu in Tibet in the 15th Century.[2] It is known as yarsha gumba in Nepal. The Latin etymology describes cord as club, ceps as head, and sinensis as Chinese. Cordyceps sinensis, known in English commonly as caterpillar fungus, is considered a medicinal mushroom in oriental medicines, such as Traditional Chinese medicines[3] and Traditional Tibetan medicine.

When a Cordyceps fungus attacks a host, the mycelium invades and eventually replaces the host tissue, while the elongated fruiting body (ascocarp) may be cylindrical, branched, or of complex shape. The ascocarp bears many small, flask-shaped perithecia contain the asci. These in turn contain the thread-like ascospores, which usually break into fragments and are presumably infective.

Some Cordyceps species are able to affect the behavior of their insect host: Cordyceps unilateralis causes ants to climb a plant and attach there before they die. This ensures the parasite's environment is at an optimal temperature and humidity and maximal distribution of the spores from the fruiting body that sprouts out of the dead insect is achieved.[4] Marks have been found on fossilised leaves which suggest this ability to modify the host's behaviour evolved more than 48 million years ago.[5]

The genus has a worldwide distribution and most of the approximately 400 species[6] have been described from Asia (notably Nepal, China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Thailand). Cordyceps species are particularly abundant and diverse in humid temperate and tropical forests.

The genus has many anamorphs (asexual states), of which Beauveria (possibly including Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium, and Isaria) are the better known, since these have been used in biological control of insect pests.

Some Cordyceps species are sources of biochemicals with interesting biological and pharmacological properties,[7] like cordycepin; the anamorph of Cordyceps subsessilis (Tolypocladium inflatum) was the source of ciclosporin—a drug helpful in human organ transplants, as it suppresses the immune system (Immunosuppressive drug).[8]

Medicinal importance

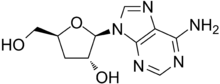

The Cordyceps mushrooms have a long history as medicinal fungi. In traditional Chinese medicine, Cordyceps have been used to treat several conditions including cancers for thousand of years. Extracts from both mycelium and fruiting bodies of C. sinensis, C. militaris and other Cordyceps species showed significant anticancer activities by various mechanisms such as, modulating immune system and inducing cell apoptosis. Some polysaccharide components and cordycepin (3'-deoxyadenosine) have been isolated from C. sinensis and C. militaris, which acted as potent anticancer components.[9]

Some work has been published in which Cordyceps sinensis has been used to protect the bone marrow and digestive systems of mice from whole body irradiation.[10] An experiment noted Cordyceps sinensis may protect the liver from damage.[11] An experiment with mice noted the mushroom may have an anti-depressant effect.[12] Researchers have noted that Cordyceps has a hypoglycemic effect and may be beneficial for people with insulin resistance.[13][14][15][16][17]

Ma Junren case

Ma Junren, the coach of a group of female Chinese athletes who broke five world records in distance running in 1993 at the National Games in Beijing, China, told reporters that the runners were taking Cordyceps at his request.[18] The number of new world records being set at a single track event caused much attention and suspicion of drug use, and the records are still widely regarded as dubious, as the athletes failed to match these performances outside of China at independently drug tested events.

Value

According to Daniel Winkler, the price of Cordyceps sinensis has risen dramatically on the Tibetan Plateau, basically 900% between 1998 and 2008, an annual average of over 20%. However, the value of big-sized caterpillar fungus has increased more dramatically than smaller size Cordyceps, regarded as lower quality.[19]

| Year | % Price increase | Price/kg (Yuan) |

|---|---|---|

| 1980s | 1,800 | |

| 1997 | 467% (incl. inflation) | 8,400 |

| 2004 | 429% (incl. inflation) | 36,000 |

| 2005 | 10,000–60,000 |

According to Modern Marvels, a show on the History Channel, mushroom hunters in Nepal can earn 900 dollars for an ounce of cordyceps.[1]

The high value of cordyceps was evidently the reason it was one of only two Chinese traditional medicines to be stolen in a brazen theft in British Columbia. The stolen cordyceps has been estimated to have been worth Can $38,000.[20]

Gallery

-

Cordyceps sinensis (caterpillar fungus), mostly whole dried choice specimens.

-

Cordyceps beginning its growth from an insect.

-

Cordyceps militaris

-

Cordyceps militaris

-

Cordyceps being weighed in at the market in China.

See also

- Medicinal mushrooms

- Caterpillar fungus

- Yarchagumba (Caterpillar fungus, Tochukaso, Dong Chong Xia Cao)

- Cordyceps information from Drugs.com.

- Medicinal Mushrooms: Their Therapeutic Properties and Current Medical Usage with Special Emphasis on Cancer Treatments by Cancer Research UK (the American equivalent to the US National Cancer Institute), 2001.[2]

References

- ^ Holliday, John (2008). "Medicinal Value of the Caterpillar Fungi Species of the Genus Cordyceps (Fr.) Link (Ascomycetes). A Review" (PDF). International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 10 (3). New York: Begell House: 219. doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v10.i3.30. ISSN 1521-9437.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Winkler, D. 2008a. Yartsa Gunbu (Cordyceps sinensis) and the Fungal Commodification of the Rural Economy in Tibet AR. Economic Botany 63.2: 291–306

- ^ Halpern, Georges M. (2007). [[Healing Mushrooms]] (PDF). Square One Publishers. pp. 65–86. ISBN 978-0-7570-0196-3.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "Neurophilosophy: Brainwashed by a parasite". 2006-11-20. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0521, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1098/rsbl.2010.0521instead. - ^ Sung, Gi-Ho (2007). "Phylogenetic classification of Cordyceps and the clavicipitaceous fungi". Stud Mycol. 57 (1): 5–59. doi:10.3114/sim.2007.57.01. PMC 2104736. PMID 18490993.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Holliday, John (2004). "Analysis of Quality and Techniques for Hybridization of Medicinal Fungus Cordyceps sinensis (Berk.)Sacc. (Ascomycetes)" (PDF). International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 6 (2). New York: Begell House: 152. ISSN 1521-9437.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Holliday, John (2005). "Cordyceps" (PDF). In Coates, Paul M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. Vol. 1. Marcel Dekker. pp. 4 of Cordyceps Chapter.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Khan MA, Tania M, Zhang D, Chen H (2010). "Cordyceps Mushroom: A Potent Anticancer Nutraceutical" (PDF). The Open Nutraceuticals Journal. 3: 179–183. doi:10.2174/1876396001003010179.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Liu, Wei-Chung; Wang, Shu-Chi; Tsai, Min-Lung; Chen, Meng-Chi; Wang, Ya-Chen; Hong, Ji-Hong; McBride, William H.; Chiang, CS (2006-12). "Protection against Radiation-Induced Bone Marrow and Intestinal Injuries by Cordyceps sinensis, a Chinese Herbal Medicine". Radiation Research. 166 (6): 900–907. doi:10.1667/RR0670.1. PMID 17149981.

{{cite journal}}:|first9=missing|last9=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ko WS, Hsu SL, Chyau CC, Chen KC, Peng RY (2009). "Compound Cordyceps TCM-700C exhibits potent hepatoprotective capability in animal model". Fitoterapia. 81 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2009.06.018. PMID 19596425.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nishizawa K, Torii K, Kawasaki A; et al. (2007). "Antidepressant-like effect of Cordyceps sinensis in the mouse tail suspension test". Biol. Pharm. Bull. 30 (9): 1758–1762. doi:10.1248/bpb.30.1758. PMID 17827735.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kiho T, Hui J, Yamane A, Ukai S (1993). "Polysaccharides in fungi. XXXII. Hypoglycemic activity and chemical properties of a polysaccharide from the cultural mycelium of Cordyceps sinensis". Biol. Pharm. Bull. 16 (12): 1291–1293. PMID 8130781.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kiho T, Yamane A, Hui J, Usui S, Ukai S (1996). "Polysaccharides in fungi. XXXVI. Hypoglycemic activity of a polysaccharide (CS-F30) from the cultural mycelium of Cordyceps sinensis and its effect on glucose metabolism in mouse liver". Biol. Pharm. Bull. 19 (2): 294–296. PMID 8850325.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhao CS, Yin WT, Wang JY; et al. (2002). "CordyMax Cs-4 improves glucose metabolism and increases insulin sensitivity in normal rats". J Altern Complement Med. 8 (3): 309–314. doi:10.1089/10755530260127998. PMID 12165188.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lo HC, Tu ST, Lin KC, Lin SC (2004). "The anti-hyperglycemic activity of the fruiting body of Cordyceps in diabetic rats induced by nicotinamide and streptozotocin". Life Sci. 74 (23): 2897–2908. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2003.11.003. PMID 15050427.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Li SP, Zhang GH, Zeng Q; et al. (2006). "Hypoglycemic activity of polysaccharide, with antioxidation, isolated from cultured Cordyceps mycelia". Phytomedicine. 13 (6): 428–433. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2005.02.002. PMID 16716913.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mackay, Duncan (2001-07-24). "Ma's army on the march again". The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

- ^ Winkler, Daniel (2008). "Yarsa Gunbu (Cordyceps sinensis) and the Fungal Commodification of the Rural Economy in Nepal". Economic Botany. 62 (3): 291–305. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9038-3.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Owsianik, Jenna (2010-07-14). "Bird's nests, fungus stolen in high-end B.C. heist". Ctvbc.ca. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

Further reading

- Bensky, D.; Gamble, A.; Clavey, S.; Stoger, E.; Lai Bensky, L. (2004). Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica (3rd ed.). Seattle: Eastland Press. ISBN 0-939616-42-4.

- Kobayasi, Y. (1941). "The genus Cordyceps and its allies". Science Reports of the Tokyo Bunrika Daigaku, Sect. B. 5: 53–260. ISSN 0371-3547.

- Mains, E. B. (1957). "Species of Cordyceps parasitic on Elaphomyces". Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 84 (4): 243–251. doi:10.2307/2482671. ISSN 0040-9618.

- Mains, E. B. (1958). "North American entomogenous species of Cordyceps". Mycologia. 50 (2): 169–222. doi:10.2307/3756193. ISSN 0027-5514.

- Tzean, S. S.; Hsieh, L. S.; Wu, W. J. (1997). Atlas of entomopathogenic fungi from Taiwan. Taiwan: Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan.

- Paterson, R. R. M. (2008). "Cordyceps - a traditional Chinese medicine and another fungal therapeutic biofactory?". Phytochemistry. 69 (7): 1469–1495. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.01.027. PMID 18343466.

External links

- Photos of Cordyceps fungi

- Independent Medicinal Research on Cordyceps

- Clinical Potential of C. sinensis by J. Howard

- Fun Facts about Cordyceps

- L'or brun du Tibet 2008 TV5 documentary coverage of Cordyceps

- BBC Planet Earth documentary coverage of Cordyceps

- Vietnamese Ministry of Health: Prof.Aca.D.Sc Dai Duy Ban with his scientists discovered Cordyceps Sinensis as Isaria cerambycidae N.SP. and Fermentation Đông Trùng Hạ Thảo Đại Fam in Vietnam

- An Electronic Monograph of Cordyceps and Related Fungi

- Cordyceps sinensis in Tibet