Combined oral contraceptive pill

| Combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background | |

| Type | Hormonal |

| First use | ? |

| Failure rates (first year) | |

| Perfect use | 0.3% |

| Typical use | 8% |

| Usage | |

| Duration effect | 1–4 days |

| Reversibility | Yes |

| User reminders | Taken within same 24-hour window each day |

| Clinic review | 6 months |

| Advantages and disadvantages | |

| STI protection | No |

| Periods | Regulates, and often lighter and less painful |

| Weight | No proven effect |

| Benefits | Reduced ovarian and endometrial cancer risks. May treat acne, PCOS, PMDD, endometriosis |

| Risks | possible small increase in some cancers,[1][2] Small reversible increase in DVTs; Stroke,[3] Cardio-vascular disease[4] |

| Medical notes | |

| Affected by the antibiotic rifampin,[5] the herb Hypericum (St. Johns Wort) and some anti-epileptics, also vomiting or diarrhea. Caution if history of migraines. | |

- "The Pill" redirects here. For other meanings, see Pill (disambiguation). This article is about daily use of COC. For occasional use, see Emergency contraception.

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), often referred to as the birth-control pill or colloquially as "the Pill", is a birth control method that includes a combination of an estrogen (oestrogen) and a progestin (progestogen). When taken by mouth every day, these pills inhibit female fertility. They were first approved for contraceptive use in the United States in 1960, and are a very popular form of birth control. They are currently used by more than 100 million women worldwide and by almost 12 million women in the United States.[6][7] Usage varies widely by country,[8] age, education, and marital status: one third of women[9] aged 16–49 in Great Britain currently use either the combined pill or a progestogen-only "minipill",[10] compared to only 1% of women in Japan.[11]

History

By the 1930s, scientists had isolated and determined the structure of the steroid hormones and found that high doses of androgens, estrogens or progesterone inhibited ovulation,[12][13][14][15] but obtaining them from European pharmaceutical companies produced from animal extracts was extraordinarily expensive.[16]

In 1939, Russell Marker, a professor of organic chemistry at Pennsylvania State University, developed a method of synthesizing progesterone from plant steroid sapogenins, initially using sarsapogenin from sarsaparilla, which proved too expensive. After three years of extensive botanical research, he discovered a much better starting material, the saponin from inedible Mexican yams (Dioscorea mexicana) found in the rain forests of Veracruz near Orizaba. The saponin could be converted in the lab to its aglycone moiety diosgenin. Unable to interest his research sponsor Parke-Davis in the commercial potential of synthesizing progesterone from Mexican yams, Marker left Penn State and in 1944 co-founded Syntex with two partners in Mexico City before leaving Syntex a year later. Syntex broke the monopoly of European pharmaceutical companies on steroid hormones, reducing the price of progesterone almost 200-fold over the next eight years.[16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28]

Midway through 20th century, the stage was set for the development of a hormonal contraceptive, but pharmaceutical companies, universities and governments showed no interest in pursuing research.[20]

Studies of progesterone to prevent ovulation

In early 1951, reproductive physiologist Gregory Pincus, a leader in hormone research and co-founder of the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology (WFEB) in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, first met American birth control movement founder Margaret Sanger at a Manhattan dinner hosted by Abraham Stone, medical director and vice president of Planned Parenthood (PPFA), who helped Pincus obtain a small grant from PPFA to begin hormonal contraceptive research. Research started on April 25, 1951 with reproductive physiologist Min Chueh Chang repeating and extending the 1937 experiments of Makepeace et al. that showed injections of progesterone suppressed ovulation in rabbits. In October 1951, G. D. Searle & Company refused Pincus' request to fund his hormonal contraceptive research, but retained him as a consultant and continued to provide chemical compounds to evaluate.[16][21]

In March 1952, Sanger wrote a brief note mentioning Pincus' research to her longtime friend and supporter, suffragist and philanthropist Katharine Dexter McCormick, who visited the WFEB and its co-founder and old friend Hudson Hoagland in June 1952 to learn about contraceptive research there. Frustrated when research stalled from PPFA's lack of interest and meager funding, McCormick arranged a meeting at the WFEB on June 6, 1953 with Sanger and Hoagland, where she first met Pincus who committed to dramatically expand and accelerate research with McCormick providing fifty times PPFA's previous funding.[21][29]

Pincus and McCormick enlisted Harvard clinical professor of gynecology John Rock, chief of gynecology at the Free Hospital for Women and an expert in the treatment of infertility, to lead clinical research with women. At a scientific conference in 1952, Pincus and Rock, who had known each other for many years, discovered they were using similar approaches to achieve opposite goals. In 1952, Rock induced a three-month anovulatory "pseudo-pregnancy" state in eighty of his infertility patients with continuous gradually increasing oral doses of estrogen (diethylstilbestrol 5–30 mg/day) and progesterone (50–300 mg/day) and within the following four months an encouraging 15% became pregnant.[21][22][30]

In 1953, at Pincus' suggestion, Rock induced a three-month anovulatory "pseudo-pregnancy" state in twenty-seven of his infertility patients with an oral 300 mg/day progesterone-only regimen for 20 days from cycle days 5–24 followed by pill-free days to produce withdrawal bleeding. This produced the same encouraging 15% pregnancy rate during the following four months without the troubling amenorrhea of the previous continuous estrogen and progesterone regimen. But 20% of the women experienced breakthrough bleeding and in the first cycle ovulation was suppressed in only 85% of the women, indicating that even higher and more expensive oral doses of progesterone would be needed to initially consistently suppress ovulation.[31]

Studies of progestins to prevent ovulation

Pincus asked his contacts at pharmaceutical companies to send him chemical compounds with progestogenic activity. Chang screened nearly 200 chemical compounds in animals and found the three most promising were Syntex's norethindrone and Searle's norethynodrel and norethandrolone.[32]

Chemists Carl Djerassi, Luis Miramontes, and George Rosenkranz at Syntex in Mexico City had synthesized the first orally highly active progestin norethindrone in 1951. Chemist Frank B. Colton at Searle in Skokie, Illinois had synthesized the orally highly active progestins norethynodrel (an isomer of norethindrone) in 1952 and norethandrolone in 1953.[16]

In December 1954, Rock began the first studies of the ovulation-suppressing potential of 5–50 mg doses of the three oral progestins for three months (for 21 days per cycle—days 5–25 followed by pill-free days to produce withdrawal bleeding) in fifty of his infertility patients in Brookline, Massachusetts. Norethindrone or norethynodrel 5 mg doses and all doses of norethandrolone suppressed ovulation but caused breakthrough bleeding, but 10 mg and higher doses of norethindrone or norethynodrel suppressed ovulation without breakthrough bleeding and led to a 14% pregnancy rate in the following five months. Pincus and Rock selected Searle's norethynodrel for the first contraceptive trials in women, citing its total lack of androgenicity versus Syntex's norethindrone's very slight androgenicity in animal tests.[33][34]

Development of an effective combined oral contraceptive

Norethynodrel (and norethindrone) were subsequently discovered to be contaminated with a small percentage of the estrogen mestranol (an intermediate in their synthesis), with the norethynodrel in Rock's 1954-5 study containing 4-7% mestranol. When further purifying norethynodrel to contain less than 1% mestranol led to breakthrough bleeding, it was decided to intentionally incorporate 2.2% mestranol, a percentage that was not associated with breakthrough bleeding, in the first contraceptive trials in women in 1956. The norethynodrel and mestranol combination was given the proprietary name Enovid.[34][35]

The first contraceptive trial of Enovid led by Edris Rice-Wray began in April 1956 in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico.[36][37][38] A second contraceptive trial of Enovid (and norethindrone) led by Edward T. Tyler began in June 1956 in Los Angeles.[19][39] On January 23, 1957, Searle held a symposium reviewing gynecologic and contraceptive research on Enovid through 1956 and concluded Enovid's estrogen content could be reduced by 33% to lower the incidence of estrogenic gastrointestinal side effects without significantly increasing the incidence of breakthrough bleeding.[40]

Public availability

United States

On June 10, 1957, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Enovid 10 mg (9.85 mg norethynodrel and 150 µg mestranol) for menstrual disorders, based on data from its use by more than 600 women. Numerous additional contraceptive trials showed Enovid at 10, 5, and 2.5 mg doses to be highly effective. On July 23, 1959, Searle filed a supplemental application to add contraception as an approved indication for 10, 5, and 2.5 mg doses of Enovid. The FDA refused to consider the application until Searle agreed to withdraw the lower dosage forms from the application. On May 9, 1960, the FDA announced it would approve Enovid 10 mg for contraceptive use, which it did on June 23, 1960, by which time Enovid 10 mg had been in general use for three years during which time, by conservative estimate, at least half a million women had used it.[23][36][41]

Although FDA-approved for contraceptive use, Searle never marketed Enovid 10 mg as a contraceptive. Eight months later, on February 15, 1961, the FDA approved Enovid 5 mg for contraceptive use. In July 1961, Searle finally began marketing Enovid 5 mg (5 mg norethynodrel and 75 µg mestranol) to physicians as a contraceptive.[23][24]

Although the FDA approved the first oral contraceptive in 1960, contraceptives were not available to married women in all states until Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965 and were not available to unmarried women in all states until Eisenstadt v. Baird in 1972.[20][24]

The first published case report of a blood clot and pulmonary embolism in a woman using Enavid (Enovid 10 mg in the U.S.) at a dose of 20 mg/day did not appear until November 1961, four years after its approval, by which time it had been used by over one million women.[36][42][43] It would take almost a decade of epidemiological studies to conclusively establish an increased risk of venous thrombosis in oral contraceptive users and an increased risk of stroke and myocardial infarction in oral contraceptive users who smoke or have high blood pressure or other cardiovascular or cerebrovascular risk factors.[23] These risks of oral contraceptives were dramatized in the 1969 book The Doctors' Case Against the Pill by feminist journalist Barbara Seaman who helped arrange the 1970 Nelson Pill Hearings called by Senator Gaylord Nelson.[44] The hearings were conducted by Senators who were all men and the witnesses in the first round of hearings were all men, leading Alice Wolfson and other feminists to protest the hearings and generate media attention.[24] Their work led to mandating the inclusion of patient package inserts with oral contraceptives to explain their possible side effects and risks to help facilitate informed consent.[45][46][47] Today's standard dose oral contraceptives contain an estrogen dose that is one third lower than the first marketed oral contraceptive and contain lower doses of different, more potent progestins in a variety of formulations.[23][24][25]

Australia

The first oral contraceptive introduced outside the United States was Schering's Anovlar (norethindrone acetate 4 mg + ethinyl estradiol 50 µg) on January 1, 1961 in Australia.[48]

Germany

The first oral contraceptive introduced in Europe was Schering's Anovlar on June 1, 1961 in West Germany.[48] The lower hormonal dose, still in use, was studied by the Belgian Gynaecologist Ferdinand Peeters.[49][50]

Britain

Before the mid-1960s, the United Kingdom did not require pre-marketing approval of drugs. The British Family Planning Association (FPA) through its clinics was then the primary provider of family planning services in Britain and provided only contraceptives that were on its Approved List of Contraceptives (established in 1934). In 1957, Searle began marketing Enavid (Enovid 10 mg in the U.S.) for menstrual disorders. Also in 1957, the FPA established a Council for the Investigation of Fertility Control (CIFC) to test and monitor oral contraceptives which began animal testing of oral contraceptives and in 1960 and 1961 began three large clinical trials in Birmingham, Slough, and London.[36][51]

In March 1960, the Birmingham FPA began trials of norethynodrel 2.5 mg + mestranol 50 µg, but a high pregnancy rate initially occurred when the pills accidentally contained only 36 µg of mestranol—the trials were continued with norethynodrel 5 mg + mestranol 75 µg (Conovid in Britain, Enovid 5 mg in the U.S.).[52] In August 1960, the Slough FPA began trials of norethynodrel 2.5 mg + mestranol 100 µg (Conovid-E in Britain, Enovid-E in the U.S.).[53] In May 1961, the London FPA began trials of Schering's Anovlar.[54]

In October 1961, at the recommendation of the Medical Advisory Council of its CIFC, the FPA added Searle's Conovid to its Approved List of Contraceptives.[55] On December 4, 1961, Enoch Powell, then Minister of Health, announced that the oral contraceptive pill Conovid could be prescribed through the NHS at a subsidized price of 2s per month.[56][57] In 1962, Schering's Anovlar and Searle's Conovid-E were added to the FPA's Approved List of Contraceptives.[36][53][54]

France

On December 28, 1967, the Neuwirth Law legalized contraception in France, including the pill.[58] The pill is the most popular form of contraception in France, especially among young women. It accounts for 60% of the birth control used in France. The abortion rate has remained stable since the introduction of the pill.[59]

Japan

In Japan, lobbying from the Japan Medical Association prevented the Pill from being approved for nearly 40 years. Two main objections raised by the association were safety concerns over long-term use of the Pill, and concerns that the Pill use would lead to diminished use of condoms and thereby potentially increase sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates.[60] As of 2004, condoms accounted for 80% of birth control use in Japan, and this may explain Japan's comparatively low rates of AIDS.[11]

The Pill was approved for use in June 1999. According to estimates, only 1.3 percent of 28 million Japanese females use the Pill, compared with 15.6 percent in the United States. The Pill prescription guidelines the government endorsed require Pill users to visit a doctor every three months for pelvic examinations and undergo tests for sexually transmitted diseases and uterine cancer. In the United States and Europe, in contrast, an annual or bi-annual clinic visit is standard for Pill users. However, as far back as 2007, many Japanese OBGYNs now only require a yearly visit for pill users, with the tri-annual visits only recommended to those who are older or at increased risk of side effects.[11]

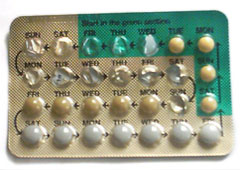

Use and packaging

Combined oral contraceptive pills should be taken at the same time each day. If one or more tablets are forgotten for more than 12 hours, contraceptive protection will be reduced.[61] Most brands of combined pills are packaged in one of two different packet sizes, with days marked off for a 28 day cycle. For the 21-pill packet, a pill is consumed daily for three weeks, followed by a week of no pills. For the 28-pill packet, 21 pills are taken, followed by week of placebo or sugar pills. A woman on the pill will have a withdrawal bleed sometime during the placebo week, and is still protected from pregnancy during this week. There are also two newer combination birth control pills (Yaz 28 and Loestrin 24 Fe) that have 24 days of active hormone pills, followed by 4 days of placebo.[62]

Placebo pills

The placebo pills allow the user to take a pill every day; remaining in the daily habit even during the week without hormones. Placebo pills may contain an iron supplement,[63][64] as iron requirements increase during menstruation.

Failure to take pills during the placebo week does not impact the effectiveness of the pill, provided that daily ingestion of active pills is resumed at the end of the week.

The withdrawal bleeding that occurs during the break from active pills was thought to be comforting, as a physical confirmation of not being pregnant.[65] The 28-day pill package also simulates the average menstrual cycle, though the hormonal events during a pill cycle are significantly different from those of a normal ovulatory menstrual cycle. The withdrawal bleeding is also predictable; as a woman goes longer periods of time taking only active pills, unexpected breakthrough bleeding becomes a more common side effect.

Less frequent placebos

If the pill formulation is monophasic, it is possible to skip withdrawal bleeding and still remain protected against conception by skipping the placebo pills and starting directly with the next packet. Attempting this with bi- or tri-phasic pill formulations carries an increased risk of breakthrough bleeding and may be undesirable. It will not, however, increase the risk of getting pregnant.

Starting in 2003, women have also been able to use a three-month version of the Pill.[66] Similar to the effect of using a constant-dosage formulation and skipping the placebo weeks for three months, Seasonale gives the benefit of less frequent periods, at the potential drawback of breakthrough bleeding. Seasonique is another version in which the placebo week every three months is replaced with a week of low-dose estrogen.

A version of the combined pill has also been packaged to completely eliminate placebo pills and withdrawal bleeds. Marketed as Anya or Lybrel, studies have shown that after seven months, 71% of users no longer had any breakthrough bleeding, the most common side effect of going longer periods of time without breaks from active pills.[67]

Effectiveness

The effectiveness of COCPs, as of most forms of contraception, can be assessed in two ways. Perfect use or method effectiveness rates only include people who take the pills consistently and correctly. Actual use, or typical use effectiveness rates are of all COCP users, including those who take the pills incorrectly, inconsistently, or both. Rates are generally presented for the first year of use.[6] Most commonly the Pearl Index is used to calculate effectiveness rates, but some studies use decrement tables.[68]

The typical use pregnancy rate among COCP users varies depending on the population being studied, ranging from 2-8% per year. The perfect use pregnancy rate of COCPs is 0.3% per year.[6]

Several factors account for typical use effectiveness being lower than perfect use effectiveness:

- mistakes on the part of those providing instructions on how to use the method

- mistakes on the part of the user

- conscious user non-compliance with instructions.

For instance, someone using oral forms of hormonal birth control might be given incorrect information by a health care provider as to the frequency of intake, or by mistake not take the pill one day, or simply not go to the pharmacy on time to renew the prescription.

COCPs provide effective contraception from the very first pill if started within five days of the beginning of the menstrual cycle (within five days of the first day of menstruation). If started at any other time in the menstrual cycle, COCPs provide effective contraception only after 7 consecutive days use of active pills, so a backup method of contraception must be used until active pills have been taken for 7 consecutive days. COCPs should be taken at approximately the same time every day.[25][69]

Contraceptive efficacy may be impaired by: 1) missing more than one active pill in a packet, 2) delay in starting the next packet of active pills (i.e., extending the pill-free, inactive or placebo pill period beyond 7 days), 3) intestinal malabsorption of active pills due to vomiting or diarrhea, 4) drug interactions with active pills that decrease contraceptive estrogen or progestogen levels.[25]

Mechanism of action

Combined oral contraceptive pills were developed to prevent ovulation by suppressing the release of gonadotropins. Combined hormonal contraceptives, including COCPs, inhibit follicular development and prevent ovulation as their primary mechanism of action.[6][25][70][71][72]

Progestogen negative feedback decreases the pulse frequency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) release by the hypothalamus, which decreases the release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and greatly decreases the release of luteinizing hormone (LH) by the anterior pituitary. Decreased levels of FSH inhibit follicular development, preventing an increase in estradiol levels. Progestogen negative feedback and the lack of estrogen positive feedback on LH release prevent a mid-cycle LH surge. Inhibition of follicular development and the absence of a LH surge prevent ovulation.[6][25][70]

Estrogen was originally included in oral contraceptives for better cycle control (to stabilize the endometrium and thereby reduce the incidence of breakthrough bleeding), but was also found to inhibit follicular development and help prevent ovulation. Estrogen negative feedback on the anterior pituitary greatly decreases the release of FSH, which inhibits follicular development and helps prevent ovulation.[6][25][70]

A secondary mechanism of action of all progestogen-containing contraceptives is inhibition of sperm penetration through the cervix into the upper genital tract (uterus and fallopian tubes) by decreasing the amount of and increasing the viscosity of the cervical mucus.[72]

Other possible secondary mechanisms may exist. For instance, the brochure for Bayer's YAZ mentions changes in the endometrial effects that reduce the likelihood of implantation of an embryo in the uterus.[73] Some pro-life groups consider such a mechanism to be abortifacient, and the existence of postfertilization mechanisms is a controversial topic. Some scientists point out that the possibility of fertilization during COCP use is very small. From this, they conclude that endometrial changes are unlikely to play an important role, if any, in the observed effectiveness of COCPs.[72] Others make more complex arguments against the existence of these mechanisms,[74] while yet other scientists argue the existing data supports such mechanisms.[75] The controversy is currently unresolved.[citation needed]

Drug interactions

Some drugs reduce the effect of the Pill and can cause breakthrough bleeding, or increased chance of pregnancy. These include drugs such as rifampicin, barbiturates, phenytoin and carbamazepine. In addition cautions are given about broad spectrum antibiotics, such as ampicillin and doxycycline, which may cause problems "by impairing the bacterial flora responsible for recycling ethinylestradiol from the large bowel" (BNF 2003).[76][77][78][79]

The traditional medicinal herb St John's Wort has also been implicated due to its upregulation of the P450 system in the liver.

Side effects

Different sources note different incidences of side effects. The most common side effect is breakthrough bleeding. A University of New Mexico Student Health Center webpage says the majority (about 60%) of women report no side effects at all, and the vast majority of those who do, have only minor effects.

A 1992 French review article said that as many as 50% of new first-time users discontinue the birth control pill before the end of the first year because of the annoyance of side effects such as breakthrough bleeding and amenorrhea.[80]

On the other hand, the pills improve conditions such as pelvic inflammatory disease, dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and acne.[81] And they reduce symptoms of endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome, and decrease the risk of anemia.[82] Use of oral contraceptives also reduces lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.[83][84]

It is generally accepted by medical authorities that the health risks of oral contraceptives are lower than those from pregnancy and birth,[85] and "the health benefits of any method of contraception are far greater than any risks from the method".[86] Some organizations have argued that comparing a contraceptive method to no method (pregnancy) is not relevant—instead, the comparison of safety should be among available methods of contraception.[87]

Venous thromboembolism

Combined oral contraceptives increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (including deep vein thrombosis(DVT) and pulmonary embolism(PE)).[88] On average the risk of fatal PE is 1 per 100,000 women.[88]

The risk of thromboembolism varies with different preparations; with second-generation pills (with an estrogen content less than 50μg), the risk of thromboembolism is small, with an incidence of approximately 15 per 100,000 users per year, compared with 5 per 100,000 per year among non-pregnant individuals not taking the pill, and 60 per 100,000 pregnancies.[89] In individuals using preparations containing third-generation progestogens (desogestrel or gestodene), the incidence of thromboembolism is approximately 25 per 100,000 users per year.[89] Also, the risk is greatest in subgroups with additional factors, such as smoking (which increases risk substantially) and long-continued use of the pill, especially in women over 35 years of age.[89]

COC confer a risk of first ischemic stroke,[3] and current use significantly increases the risk of cardio-vascular disease among those at high risk.[4]

Cancer

A systematic review in 2010, which looked at several previous studies of multiple types of cancer, did not support an increased cancer risk in users of combined oral contraceptive pill.[90]

COC decrease the risk of ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer,[25] and colorectal cancer.[1][91]

Monograph 91 of The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) stated in 2005 that COC increase the risk of cancers of the breast (among current and recent users),[1] cervix and liver (among populations at low risk of hepatitis B virus infection).[1][92] Research into the relationship between breast cancer risk and hormonal contraception is complex and seemingly contradictory.[93] The large 1996 collaborative reanalysis of individual data on over 150,000 women in 54 studies of breast cancer found that: "The results provide strong evidence for two main conclusions. First, while women are taking combined oral contraceptives and in the 10 years after stopping there is a small increase in the relative risk of having breast cancer diagnosed. Second, there is no significant excess risk of having breast cancer diagnosed 10 or more years after stopping use. The cancers diagnosed in women who had used combined oral contraceptives were less advanced clinically than those diagnosed in women who had never used these contraceptives."[2] This data has been interpreted to suggest that oral contraceptives have little or no biological effect on breast cancer development, but that women who seek gynecologic care to obtain contraceptives have more early breast cancers detected through screening.[94][95] It has been estimated that, while taking the pill, there are approximately 0.5 excess cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women aged 16–19, and approximately 5 excess cases per 10,000 women aged 25–29.[89]

Weight

The same 1992 French review article noted that in the subgroup of adolescents 15–19 years of age in the 1982 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) who had stopped taking the Pill, 20–25% reported they stopped taking the Pill because of either acne or weight gain, and another 25% stopped because of fear of cancer.[80] A 1986 Hungarian study comparing two high-dose estrogen (both 50 µg ethinyl estradiol) pills found that women using a lower-dose biphasic levonorgestrel formulation (50 µg levonorgestrel x 10 days + 125 µg levonorgestrel x 11 days) reported a significantly lower incidence of weight gain compared to women using a higher-dose monophasic levonorgestrel formulation (250 µg levonorgestrel x 21 days).[96]

Many clinicians consider the public perception of weight gain on the Pill to be inaccurate and dangerous. The aforementioned 1992 French review article noted that one unpublished 1989 study by Professor Elizabeth Connell at Emory University of 550 women found that 23% of the 6% of women who discontinued the Pill because of poor cycle control experienced subsequent unwanted pregnancies.[80] A 2000 British review article concluded there is no evidence that modern low-dose pills cause weight gain, but that fear of weight gain contributed to poor compliance in taking the Pill and subsequent unintended pregnancy, especially among adolescents.[97]

Sexuality

COCPs may increase natural vaginal lubrication.[98] Other women experience reductions in libido while on the pill, or decreased lubrication.[98][99] Some researchers question a causal link between COCP use and decreased libido;[100] a 2007 study of 1700 women found COCP users experienced no change in sexual satisfaction.[101] A 2005 laboratory study of genital arousal tested fourteen women before and after they began taking COCPs. The study found that women experienced a significantly wider range of arousal responses after beginning pill use; decreases and increases in measures of arousal were equally common.[102]

A 2006 study of 124 pre-menopausal women measured sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), including before and after discontinuation of the oral contraceptive pill. Women continuing use of oral contraceptives had SHBG levels four times higher than those who never used it, and levels remained elevated even in the group that had discontinued its use.[103] Theoretically, an increase in SHBG may be a physiologic response to increased hormone levels, but may decrease the free levels of other hormones, such as androgens, because of the unspecificity of its sex hormone binding.

Depression

Low levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter in the brain, have been linked to depression. High levels of estrogen, as in first-generation COCPs, and progestin, as in some progestin-only contraceptives, have been shown to promote the lowering of brain serotonin levels by increasing the concentration of a brain enzyme that reduces serotonin.[6] This observation, along with some small research studies[104] have inspired speculation that the pill causes depression.

Progestin-only contraceptives are known to worsen the condition of women who are already depressed.[105] However, current medical reference textbooks on contraception[25] and major organizations such as the American ACOG,[106] the WHO,[107] and the United Kingdom's RCOG[108] agree that current evidence indicates low-dose combined oral contraceptives are unlikely to increase the risk of depression, and unlikely to worsen the condition in women that are currently depressed. Contraceptive Technology states that low-dose COCPs have not been implicated in disruptions of serotonin or tryptophan.[6] However, some studies provide evidence to contradict this last claim.[109]

Hypertension

Bradykinin lowers blood pressure by causing blood vessel dilation. Certain enzymes are capable of breaking down bradykinin ( Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, Aminopeptidase P). Progesterone can increase the levels of Aminopeptidase P (AP-P), thereby increasing the breakdown of bradykinin, which increases the risk of developing hypertension.[110]

Other effects

Other side effects associated with low-dose COCPs are leukorrhea (increased vaginal secretions), reductions in menstrual flow, mastalgia (breast tenderness), and decrease in acne. Side effects associated with older high-dose COCPs include nausea, vomiting, increases in blood pressure, and melasma (facial skin discoloration); these effects are not strongly associated with low-dose formulations.

Excess estrogen, such as from birth control pills, appears to increase cholesterol levels in bile and decrease gallbladder movement, which can lead to gallstones.[111]

Progestins found in certain formulations of oral contraceptive pills can limit the effectiveness of weight training to increase muscle mass.[112] This effect is caused by the ability of some progestins to inhibit androgen receptors.

One study claims that the pill may affect what male body odors a woman prefers, which may in turn influence her selection of partner.[113]

Contraindications

Combined oral contraceptives are generally accepted to be contraindicated in women with pre-existing cardiovascular disease, in women who have a familial tendency to form blood clots (such as familial factor V Leiden), women with severe obesity and/or hypercholesterolemia (high cholesterol level), and in smokers over age 40.

COC are also contraindicated for women with liver tumors, hepatic adenoma or severe cirrhosis of the liver, and for those with known or suspected breast cancer. (WHO category 4).

Health benefits

Overall, use of oral contraceptives appears to slightly reduce all-cause mortality, with a rate ratio for overall mortality of 0.87 (confidence interval: 0.79–0.96) when comparing ever-users of OCs with never-users.[114]

The use of oral contraceptives (birth control pills) for five years or more decreases the risk of ovarian cancer in later life by 50%.[91] Combined oral contraceptive use reduces the risk of ovarian cancer by 40% and the risk of endometrial cancer by 50% compared to never users. The risk reduction increases with duration of use, with an 80% reduction in risk for both ovarian and endometrial cancer with use for more than 10 years. The risk reduction for both ovarian and endometrial cancer persists for at least 20 years.[25]

Taking oral contraceptives also reduces the risk of colorectal cancer, and improves conditions such as pelvic inflammatory disease, dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and acne.[81] Additionally, birth control pills reduce symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome, and decrease the risk of anemia.[82]

Use of combined oral contraceptives is associated with a reduced risk of endometriosis, giving a relative risk of endometriosis of 0.63 during active use, yet with limited quality of evidence according to a systematic review.[115]

Formulations

Oral contraceptives come in a variety of formulations. The main division is between combined oral contraceptive pills, containing both estrogen and progestins and progestin only pills. Combined oral contraceptive pills also come in varying types, including varying doses of estrogen, and whether the dose of estrogen or progestin changes from 1 week to the next.

Non-contraceptive uses

The hormones in "the Pill" can also be used to treat other medical conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, adenomyosis, menstruation-related anemia and painful menstruation (dysmenorrhea). In addition, oral contraceptives are often prescribed as medication for mild or moderate acne.[116] The pill can also induce menstruation on a regular schedule for women bothered by irregular menstrual cycles or disorders where there is dysfunctional uterine bleeding. In addition, the Pill provides some protection against breast growth that is not cancer, ectopic pregnancy, vaginal dryness and menopause-related painful intercourse.

Social and cultural impact

The Pill was approved by the FDA in the early 1960s; its use spread rapidly in the late part of that decade, generating an enormous social impact. Time magazine placed the pill on its cover in April, 1967.[117] In the first place, it was more effective than most previous reversible methods of birth control, giving women unprecedented control over their fertility.[citation needed] Its use was separate from intercourse, requiring no special preparations at the time of sexual activity that might interfere with spontaneity or sensation, and the choice to take the Pill was a private one. This combination of factors served to make the Pill immensely popular within a few years of its introduction.[17][24] Claudia Goldin, among others, argue that this new contraceptive technology was a key player in forming women's modern economic role, in that it prolonged the age at which women first married allowing them to invest in education and other forms of human capital as well as generally become more career-oriented. Soon after the birth control pill was legalized, there was a sharp increase in college attendance and graduation rates for women.[118] From an economic point of view, the birth control pill reduced the cost of staying in school. The ability to control fertility without sacrificing sexual relationships allowed women to make long term educational and career plans.

Because the Pill was so effective, and soon so widespread, it also heightened the debate about the moral and health consequences of pre-marital sex and promiscuity. Never before had sexual activity been so divorced from reproduction. For a couple using the Pill, intercourse became purely an expression of love, or a means of physical pleasure, or both; but it was no longer a means of reproduction. While this was true of previous contraceptives, their relatively high failure rates and their less widespread use failed to emphasize this distinction as clearly as did the Pill. The spread of oral contraceptive use thus led many religious figures and institutions to debate the proper role of sexuality and its relationship to procreation. The Roman Catholic Church in particular, after studying the phenomenon of oral contraceptives, re-emphasized the stated teaching on birth control in the 1968 papal encyclical Humanae Vitae. The encyclical reiterated the established Catholic teaching that artificial contraception distorts the nature and purpose of sex.[119]

A backlash against oral contraceptives occurred in the early and mid-1970s, when reports and speculations appeared that linked the use of the Pill to breast cancer. Until then, many women in the feminist movement had hailed the Pill as an "equalizer" that had given them the same sexual freedom as men had traditionally enjoyed. This new development, however, caused many of them to denounce oral contraceptives as a male invention designed to facilitate male sexual freedom with women at the cost of health risk to women.[120]

The United States Senate began hearings on the Pill in 1970 and there were different viewpoints heard from medical professionals. Dr. Michael Newton, President of the College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said:

"The evidence is not yet clear that these still do in fact cause cancer or related to it. The FDA Advisory Committee made comments about this, that if there wasn't enough evidence to indicate whether or not these pills were related to the development of cancer, and I think that's still thin; you have to be cautious about them, but I don't think there is clear evidence, either one way or the other, that they do or don't cause cancer."[121]

Another physician, Dr. Roy Hertz of the Population Council, said that anyone who takes this should know of "our knowledge and ignorance in these matters" and that all women should be made aware of this so she can decide to take the Pill or not.[121]

The Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare at the time, Robert Finch announced the federal government had accepted a compromise warning statement which would accompany all sales of birth control pills.[121]

At the same time, society was beginning to take note of the impact of the Pill on traditional gender roles. Women now did not have to choose between a relationship and a career; singer Loretta Lynn commented on this in her 1974 album with a song entitled "The Pill", which told the story of a married woman's use of the drug to liberate herself from her traditional role as wife and mother.

It can be noted that the spread of the use of the contraceptive pill in the late 1960s lead to a rise in female employment. Women no longer had to choose between having a relationship and a career and could actively pursue both. This is evidenced by the fact that there was a dramatically large increase in female employment at the time the pill became available. States that allowed unmarried women to use the pill were also those that had higher rates of females in the workforce, especially in advanced professional careers.

Environmental impact

A woman using COCPs excretes from her urine and feces natural estrogens, estrone (E1) and estradiol (E2), and synthetic estrogen ethinylestradiol (EE2) into water treatment plants.[122] These hormones can pass through water treatment plants and into rivers.[123] Other forms of contraception, such as the contraceptive patch, use the same synthetic estrogen (EE2) that is found in COCPs, and can add to the hormonal concentration in the water when flushed down the toilet.[124] This excretion is shown to play a role in causing endocrine disruption, which affects the sexual development and the reproduction, in wild fish populations in segments of streams contaminated by treated sewage effluents.[122][125] A study done in British rivers supported the hypothesis that the incidence and the severity of intersex wild fish populations were significantly correlated with the concentrations of the E1, E2, and EE2 in the rivers.[122]

A review of activated sludge plant performance found estrogen removal rates varied considerably but averaged 78% for estrone, 91% for estradiol, and 76% for ethinylestradiol (estriol effluent concentrations are between those of estrone and estradiol, but estriol is a much less potent endocrine disruptor to fish).[126] Effluent concentrations of ethinylestradiol are lower than estradiol which are lower than estrone, but ethinylestradiol is more potent than estradiol which is more potent than estrone in the induction of intersex fish and synthesis of vitellogenin in male fish.[127]

References

- ^ a b c d "Combined Estrogen-Progestogen Contraceptives" (PDF). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 91. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2007.

- ^ a b Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (1996). "Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies". Lancet. 347 (9017): 1713–27. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90806-5. PMID 8656904.

- ^ a b Jeanet M. Kemmeren, Bea C. Tanis, Maurice A.A.J. van den Bosch, Edward L.E.M. Bollen, Frans M. Helmerhorst, Yolanda van der Graaf, Frits R. Rosendaal, and Ale Algra (2002). "Risk of Arterial Thrombosis in Relation to Oral Contraceptives (RATIO) Study: Oral Contraceptives and the Risk of Ischemic Stroke". Stroke. 33 (5). American Heart Association, Inc.: 1202–1208. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000015345.61324.3F. PMID 11988591.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Jean-Patrice Baillargeon, Donna K. McClish, Paulina A. Essah, and John E. Nestler (2005). "Association between the Current Use of Low-Dose Oral Contraceptives and Cardiovascular Arterial Disease: A Meta-Analysis". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 90 (7). The Endocrine Society: 3863–3870. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1958. PMID 15814774.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Planned Parenthood - Birth Control Pills

- ^ a b c d e f g h Trussell, James (2007). "Contraceptive Efficacy". In Hatcher, Robert A.; et al. (eds.). Contraceptive Technology (19th rev. ed.). New York: Ardent Media. ISBN 0-9664902-0-7.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "hatcher" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Mosher WD, Martinez GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Willson SJ (2004). "Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982–2002" (PDF). Adv Data (350): 1–36. PMID 15633582.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) all US women aged 15–44 - ^ UN Population Division (2006). World Contraceptive Use 2005 (PDF). New York: United Nations. ISBN 9-211-51418-5. women aged 15–49 married or in consensual union

- ^ Dr. David Delvin. "Contraception – the contraceptive pill: How many women take it in the UK?".

- ^ Taylor, Tamara; Keyse, Laura; Bryant, Aimee (2006). Contraception and Sexual Health, 2005/06 (PDF). London: Office for National Statistics. ISBN 1-85774-638-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) British women aged 16–49: 24% currently use the Pill (17% use Combined pill, 5% use Minipill, 2% don't know type) - ^ a b c Aiko Hayashi (2004-08-20). "Japanese Women Shun The Pill". CBS News. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ^ Goldzieher JW, Rudel HW (1974). "How the oral contraceptives came to be developed". JAMA. 230 (3): 421–5. doi:10.1001/jama.230.3.421. PMID 4606623.

- ^ Goldzieher JW (1982). "Estrogens in oral contraceptives: historical perspective". Johns Hopkins Med J. 150 (5): 165–9. PMID 7043034.

- ^ Perone N (1993). "The history of steroidal contraceptive development: the progestins". Perspect Biol Med. 36 (3): 347–62. PMID 8506121.

- ^ Goldzieher JW (1993). "The history of steroidal contraceptive development: the estrogens". Perspect Biol Med. 36 (3): 363–8. PMID 8506122.

- ^ a b c d Maisel, Albert Q. (1965). The Hormone Quest. New York: Random House.

- ^ a b Asbell, Bernard (1995). The Pill: A Biography of the Drug That Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-43555-7.

- ^ Lehmann PA, Bolivar A, Quintero R (1973). "Russell E. Marker. Pioneer of the Mexican steroid industry". J Chem Educ. 50 (3): 195–9. doi:10.1021/ed050p195. PMID 4569922.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Vaughan, Paul (1970). The Pill on Trial. New York: Coward-McCann.

- ^ a b c Tone, Andrea (2001). Devices & Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-809-03817-X.

- ^ a b c d Reed, James (1978). From Private Vice to Public Virtue: The Birth Control Movement and American Society Since 1830. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-02582-X.

- ^ a b McLaughlin, Loretta (1982). The pill, John Rock, and the Church: The Biography of a Revolution. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-56095-2.

- ^ a b c d e Marks, Lara V (2001). Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08943-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Watkins, Elizabeth Siegel (1998). On the Pill: A Social History of Oral Contraceptives, 1950–1970. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-85876-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Speroff, Leon; Darney, Philip D. (2005). "Oral Contraception". A Clinical Guide for Contraception (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 21–138. ISBN 0-781-76488-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Djerassi, Carl (2001). This man's pill: reflections on the 50th birthday of the pill. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 11–62. ISBN 0198508727.

- ^ Applezweig, Norman (1962). Steroid drugs. New York: Blakiston Division, McGraw-Hill. vii–xi, 9–83.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Gereffi, Gary (1983). The pharmaceutical industry and dependency in the Third World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 53–163. ISBN 0691094012.

- ^ Fields, Armond (2003). Katharine Dexter McCormick: Pioneer for Women's Rights. Westport: Prager. ISBN 0-275-98004-9.

- ^ Rock J, Garcia CR, Pincus G (1957). "Synthetic progestins in the normal human menstrual cycle". Recent Prog Horm Res. 13: 323–39. PMID 13477811.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pincus G (1958). "The hormonal control of ovulation and early development". Postgrad Med. 24 (6): 654–60. PMID 13614060.

- ^ Chang MC (1978). "Development of the oral contraceptives". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 132 (2): 217–9. PMID 356615.

- ^ Garcia CR, Pincus G, Rock J (1956). "Effects of certain 19-nor steroids on the normal human menstrual cycle". Science. 124 (3227): 891–3. doi:10.1126/science.124.3227.891. PMID 13380401.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rock, John; Garcia, Celso R. (1957). "Observed effects of 19-nor steroids on ovulation and menstruation". In in (ed.). Proceedings of a Symposium on 19-Nor Progestational Steroids. Chicago: Searle Research Laboratories. pp. 14–31.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pincus G, Rock J, Garcia CR, Rice-Wray E, Paniagua M, Rodgriquez I (1958). "Fertility control with oral medication". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 75 (6): 1333–46. PMID 13545267.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Junod SW, Marks L (2002). "Women's trials: the approval of the first oral contraceptive pill in the United States and Great Britain" (PDF). J Hist Med Allied Sci. 57 (2): 117–60. doi:10.1093/jhmas/57.2.117. PMID 11995593.

- ^ Ramírez de Arellano, Annette B.; Seipp, Conrad (1983). Colonialism, Catholicism, and Contraception: A History of Birth Control in Puerto Rico. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-807-81544-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rice-Wray, Edris (1957). "Field Study with Enovid as a Contraceptive Agent". In in (ed.). Proceedings of a Symposium on 19-Nor Progestational Steroids. Chicago: Searle Research Laboratories. pp. 78–85.

- ^ Tyler ET, Olson HJ (1959). "Fertility promoting and inhibiting effects of new steroid hormonal substances". JAMA. 169 (16): 1843–54. PMID 13640942.

- ^ Winter IC (1957). "Summary". In in (ed.). Proceedings of a Symposium on 19-Nor Progestational Steroids. Chicago: Searle Research Laboratories. pp. 120–2.

- ^ Winter IC (1970). "Industrial pressure and the population problem—the FDA and the pill". JAMA. 212 (6): 1067–8. doi:10.1001/jama.212.6.1067. PMID 5467404.

- ^ Winter IC (1965). "The incidence of thromboembolism in Enovid users". Metabolism. 14 (Suppl): 422–8. doi:10.1016/0026-0495(65)90029-6. PMID 14261427.

- ^ Jordan WM, Anand JK (1961). "Pulmonary embolism". Lancet. 278 (7212): 1146–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(61)91061-3.

- ^ Seaman, Barbara (1969). The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill. New York: P. H. Wyden. ISBN 0385145756.

- ^ FDA (1970). "Statement of Policy Concerning Oral Contraceptive Labeling Directed to Users". Fed Regist. 35 (113): 9001–3.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ FDA (1978). "Oral Contraceptives; Requirement for Labeling Directed to the Patient". Fed Regist. 43 (21): 4313–34.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ FDA (1989). "Oral Contraceptives; Patient Package Insert Requirement". Fed Regist. 54 (100): 22585–8.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Archived 2008-04-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "De vergeten Belgische stiefvader van de pil (The forgotten Belgian stepfather of the pill)" (in Dutch). March 2, 2010.

- ^ Sabine Clappaert (May 24, 2010). "The little pill that could". Flanders Today.

- ^ Mears E (November 4, 1961). "Clinical trials of oral contraceptives". Br Med J. 2 (5261): 1179–83. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5261.1179. PMC 1970272. PMID 14471934.

- ^ Eckstein P, Waterhouse JA, Bond GM, Mills WG, Sandilands DM, Shotton DM (November 4, 1961). "The Birmingham oral contraceptive trial". Br Med J. 2 (5261): 1172–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5261.1172. PMC 1970253. PMID 13889122.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Pullen D (October 20, 1962). "'Conovid-E' as an oral contraceptive". Br Med J. 2 (5311): 1016–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5311.1016. PMC 1926317. PMID 13972503.

- ^ a b Mears E, Grant EC (July 14, 1962). "'Anovlar' as an oral contraceptive". Br Med J. 2 (5297): 75–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5297.75. PMC 1925289. PMID 14471933.

- ^ "Annotations: Pill at F.P.A. clinics". Br Med J. 2 (5258): 1009. October 14, 1961. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3490.1009. PMC 1970146. PMID 20789252.

"Medical news: Oral contraceptives and the F.P.A." Br Med J. 2 (5258): 1032. October 14, 1961. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5258.1032. PMC 1970195. - ^ "Medical News: Contraceptive Pill". Br Med J. 2 (5266): 1584. December 9, 1961. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5266.1584. PMC 1970619.

- ^ "Subsidizing birth control". Time. Vol. 78, no. 24. December 15, 1961. p. 55.

- ^ Dourlen Rollier, AV (1972). "Contraception: yes, but". Fertilite, orthogenie. 4 (4): 185–8. PMID 12306278.

- ^ "The Aids Generation: the pill takes priority?". Science Actualities. 2000. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

- ^ "Djerassi on birth control in Japan - abortion 'yes,' pill 'no'" (Press release). Stanford University News Service. 96-14-02. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Organon (2001). "Mercilon SPC (Summary of Product Characteristics". Retrieved 2007-04-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Stacey, Dawn. Birth Control Pills. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ^ "US Patent:Oral contraceptive:Patent 6451778 Issued on September 17, 2002 Estimated Expiration Date: July 2, 2017". PatentStorm LLC. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Serge Herceberg; Paul Preziosi; Pilar Galan. "Iron deficiency in Europe" (PDF). Public Health Nutrition: 4(2B): 537–545. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Gladwell, Malcolm (2000-03-10). "John Rock's Error". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ "FDA Approves Seasonale Oral Contraceptivel". 2003-09-25. Archived from the original on 2006-10-07. Retrieved 2006-11-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wheldon, Julie (2005-12-28). "New Pill will eliminate menstruation". Daily Mail. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ Kippley, John (1996). The Art of Natural Family Planning (4th ed.). Cincinnati, OH: The Couple to Couple League. p. 141. ISBN 0-926412-13-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ FFPRHC (2007). "Clinical Guidance: First Prescription of Combined Oral Contraception" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ a b c Loose, Davis S.; Stancel, George M. (2006). "Estrogens and Progestins". In Brunton, Laurence L.; Lazo, John S.; Parker, Keith L. (eds.) (ed.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1541–1571. ISBN 0-07-142280-3.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Glasier, Anna (2006). "Contraception". In DeGroot, Leslie J.; Jameson, J. Larry (eds.) (ed.). Endocrinology (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 2993–3003. ISBN 0-7216-0376-9.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b c Rivera R, Yacobson I, Grimes D (1999). "The mechanism of action of hormonal contraceptives and intrauterine contraceptive devices". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 181 (5 Pt 1): 1263–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70120-1. PMID 10561657.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bayer. "YAZ® (drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol) Tablets" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-02-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Crockett, Susan A. (April 1999). "Hormone Contraceptives Controversies and Clarifications". American Association of Pro Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Larimore WL, Stanford JB (2000). "Postfertilization effects of oral contraceptives and their relationship to informed consent" (PDF). Arch Fam Med. 9 (2): 126–33. doi:10.1001/archfami.9.2.126. PMID 10693729. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ The effects of broad-spectrum antibiotics on Combined contraceptive pills is not found on systematic interaction metanalysis (Archer, 2002), although "individual patients do show large decreases in the plasma concentrations of ethinylestradiol when they take certain other antibiotics" (Dickinson, 2001). "...experts on this topic still recommend informing oral contraceptive users of the potential for a rare interaction" (DeRossi, 2002) and this remains current (2006) UK Family Planning Association advice.

- ^ Archer J, Archer D (2002). "Oral contraceptive efficacy and antibiotic interaction: a myth debunked". J Am Acad Dermatol. 46 (6): 917–23. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120448. PMID 12063491.

- ^ Dickinson B, Altman R, Nielsen N, Sterling M (2001). "Drug interactions between oral contraceptives and antibiotics". Obstet Gynecol. 98 (5 Pt 1): 853–60. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01532-0. PMID 11704183.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DeRossi S, Hersh E (2002). "Antibiotics and oral contraceptives". Dent Clin North Am. 46 (4): 653–64. doi:10.1016/S0011-8532(02)00017-4. PMID 12436822.

- ^ a b c Serfaty D (1992). "Medical aspects of oral contraceptive discontinuation". Adv Contracept. 8 (Suppl 1): 21–33. doi:10.1007/BF01849448. PMID 1442247.

Sanders, Stephanie A. (2001). "A prospective study of the effects of oral contraceptives on sexuality and well-being and their relationship to discontinuation". Contraception. 64 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00218-9. PMID 11535214. Retrieved 2007-03-02.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Huber JC, Bentz EK, Ott J, Tempfer CB (2008). "Non-contraceptive benefits of oral contraceptives". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 9 (13): 2317–25. doi:10.1517/14656566.9.13.2317. PMID 18710356.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Nelson, Randy J. (2005). An introduction to behavioral endocrinology (3rd ed.). Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-617-3.

- ^ Vo C, Carney ME (2007). "Ovarian cancer hormonal and environmental risk effect". Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 34 (4): 687–700, viii. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2007.09.008. PMID 18061864.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bandera CA (2005). "Advances in the understanding of risk factors for ovarian cancer". J Reprod Med. 50 (6): 399–406. PMID 16050564.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Crooks, Robert L. and Karla Baur (2005). Our Sexuality. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. ISBN 0-534-65176-3.

- ^ WHO (2005). Decision-Making Tool for Family Planning Clients and Providers Appendix 10: Myths about contraception

- ^ Holck, Susan. "Contraceptive Safety". Special Challenges in Third World Women's Health. 1989 Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association. Retrieved 2006-10-07.

- ^ a b Blanco-Molina, A (2010 Feb). "Venous thromboembolism in women taking hormonal contraceptives". Expert review of cardiovascular therapy. 8 (2): 211–5. doi:10.1586/erc.09.175. PMID 20136607.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Chapter 30 - The reproductive system in: Rod Flower; Humphrey P. Rang; Maureen M. Dale; Ritter, James M. (2007). Rang & Dale's pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-06911-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq022, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1093/humupd/dmq022instead. - ^ a b Bast RC, Brewer M, Zou C; et al. (2007). "Prevention and early detection of ovarian cancer: mission impossible?". Recent Results Cancer Res. 174: 91–100. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-37696-5_9. PMID 17302189.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Karen Malec (2005-08-31). "World Health Organization: Oral Contraceptives and Menopausal Therapy Are 'Carcinogenic to Humans / Scientists' Findings Provide Additional Biological Support for an Abortion-Breast Cancer Link, Abortion Breast Cancer" (Press release). Coalition on Abortion/Breast Cancer.

- ^ FPA (2005). "The combined pill - Are there any risks?". Family Planning Association (UK). Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (1996). "Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: further results". Contraception. 54 (3 Suppl): 1S – 106S. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(96)00111-4. PMID 8899264.

- ^ Plu-Bureau G, Lê M (1997). "Oral contraception and the risk of breast cancer". Contracept Fertil Sex. 25 (4): 301–5. PMID 9229520. - pooled re-analysis of original data from 54 studies representing about 90% of the published epidemiological studies, prior to introduction of third generation pills.

- ^ Balogh A (1986). "Clinical and endocrine effects of long-term hormonal contraception". Acta Med Hung. 43 (2): 97–102. PMID 3588164.

- ^ Gupta S (2000). "Weight gain on the combined pill—is it real?". Hum Reprod Update. 6 (5): 427–31. doi:10.1093/humupd/6.5.427. PMID 11045873.

- ^ a b Hatcher & Nelson (2004). "Combined Hormonal Contraceptive Methods". In Hatcher, Robert D. (ed.). Contraceptive technology (18th ed.). New York: Ardent Media, Inc. pp. 403, 432, 434. ISBN 0-9664902-5-8.

- ^ Darney, Philip D.; Speroff, Leon (2005). A clinical guide for contraception (4th ed.). Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 72. ISBN 0-7817-6488-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weir, Gordon C.; DeGroot, Leslie Jacob; Grossman, Ashley; Marshall, John F.; Melmed, Shlomo; Potts, John T. (2006). Endocrinology (5th ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. p. 2999. ISBN 0-7216-0376-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Westhoff CL, Heartwell S, Edwards S; et al. (2007). "Oral contraceptive discontinuation: do side effects matter?". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 196 (4): 412.e1–6, discussion 412.e6–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.015. PMC 1903378. PMID 17403440.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Seal, Brooke N.; Brotto, Lori A.; Gorzalka, Boris B. (2005). "Oral contraceptive use and female genital arousal: Methodological considerations". Journal of Sex Research. 42 (3): 249–258. doi:10.1080/00224490509552279. PMID 19817038.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Panzer MD, Claudia (2006). "WOMEN's SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION: Impact of Oral Contraceptives on Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin and Androgen Levels: A Retrospective Study in Women with Sexual Dysfunction". Journal of Sexual Medicine. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00198.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Description of the study results in Medical News Today: "Birth Control Pill Could Cause Long-Term Problems With Testosterone, New Research Indicates". January 4, 2006. - ^ Kulkarni, Jayashri (2005-03-01). "Contraceptive Pill Linked to Depression". Monash Newsline. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ^ Katherine Burnett-Watson (October 2005). "Is The Pill Playing Havoc With Your Mental Health?". Retrieved 2007-03-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help), which cites:- Kulkarni J, Liew J, Garland K (2005). "Depression associated with combined oral contraceptives—a pilot study". Aust Fam Physician. 34 (11): 990. PMID 16299641.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kulkarni J, Liew J, Garland K (2005). "Depression associated with combined oral contraceptives—a pilot study". Aust Fam Physician. 34 (11): 990. PMID 16299641.

- ^ ACOG (2006). "Practice bulletin No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions". Obstet Gynecol. 107 (6): 1453–72. doi:10.1097/00006250-200606000-00055. PMID 16738183.

- ^ WHO (2004). "Low-dose combined oral contraceptives". Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (3rd ed.). Geneva: Reproductive Health and Research, WHO. ISBN 92-4-156266-8.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ FFPRHC (2006). "The UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (2005/2006)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-19. Retrieved 2007-03-31.

- ^ Rose DP, Adams PW (1972). "Oral contraceptives and tryptophan metabolism: effects of oestrogen in low dose combined with a progestagen and of a low-dose progestagen (megestrol acetate) given alone". J. Clin. Pathol. 25 (3): 252–8. doi:10.1136/jcp.25.3.252. PMC 477273. PMID 5018716.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cilia La Corte AL, Carter AM, Turner AJ, Grant PJ, Hooper NM (2008). "The bradykinin-degrading aminopeptidase P is increased in women taking the oral contraceptive pill". J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 9 (4): 221–5. doi:10.1177/1470320308096405. PMID 19126663.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Gallstones". NDDIC. 2007-07. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Raloff, Janet. (23 April 2011)) "Birth control pills can limit muscle-training gains". Science News. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Love woes can be blamed on contraceptive pill: research - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. 2008-08-14. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ Vessey M, Yeates D, Flynn S. (2010 Sep). "Factors affecting mortality in a large cohort study with special reference to oral contraceptive use". Contraception. 82 (3): 221–9. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.04.006. PMID 20705149.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq042, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1093/humupd/dmq042instead. - ^ Huber J, Walch K (2006). "Treating acne with oral contraceptives: use of lower doses". Contraception. 73 (1): 23–9. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2005.07.010. PMID 16371290.

- ^ "TIME Magazine Cover: The Pill". Time.com. April 7, 1967. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence Katz (2002). "The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women's Career and Marriage Decisions". Journal of Political Economy. 110 (4): 730–770. doi:10.1086/340778.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ George Weigel (2002). The Courage to Be Catholic: Crisis, Reform, and the Renewal of the Church. Basic Books.

- ^ Andrea Dworkin (1976). Our Blood: Prophecies and Discourses on Sexual Politics. Harper & Row. ISBN 006011116X.

- ^ a b c "1970 Year in Review". UPI.

- ^ a b c Williams RJ, Johnson AC, Smith JJ, Kanda R (2003). "Steroid estrogens profiles along river stretches arising from sewage treatment works discharges". Environ Sci Technol. 37 (9): 1744–50. doi:10.1021/es0202107. PMID 12775044.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ A.T. (2003). "Not Quite Worry-Free". Environment. 45 (1): 6–7.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Batt, Sharon (Spring 2005). "Pouring Drugs Down the Drain" (PDF). Herizons. 18 (4): 12–3.

- ^ Zeilinger J, Steger-Hartmann T, Maser E, Goller S, Vonk R, Länge R (2009). "Effects of synthetic gestagens on fish reproduction". Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 28 (12): 2663–70. doi:10.1897/08-485.1. PMID 19469587.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson AC, Williams RJ, Simpson P, Kanda R (2007). "What difference might sewage treatment performance make to endocrine disruption in rivers?". Environ Pollut. 147 (1): 194–202. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2006.08.032. PMID 17030080.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson AC, Williams RJ (2004). "A model to estimate influent and effluent concentrations of estradiol, estrone, and ethinylestradiol at sewage treatment works". Environ Sci Technol. 38 (13): 3649–58. doi:10.1021/es035342u. PMID 15296317.

External links

- The Birth Control Pill—‚CBC Digital Archives

- The Pill—PBS.org

- The Birth of the Pill—slide show by Life magazine