Macrauchenia

| Macrauchenia Temporal range: Late Miocene to Late Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Phenacodus primaevus (smaller) and Macrauchenia patachonica (larger) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | †Macrauchenia

|

| Type species | |

| Macrauchenia patachonica Owen, 1838

| |

| Species | |

|

†M. patachonica | |

Macrauchenia ("long llama", based on the now superseded Latin term for llamas, Auchenia, from Greek terms which literally mean "big neck") was a long-necked and long-limbed, three-toed South American ungulate mammal, typifying the order Litopterna. The oldest fossils date back to around 7 million years ago, and M. patachonica disappears from the fossil record during the late Pleistocene, around 20,000-10,000 years ago. M. patachonica was the best known member of the family Macraucheniidae, and is known only from fossil finds in South America, primarily from the Lujan Formation in Argentina. The original specimen was discovered by Charles Darwin during the voyage of the Beagle. In life, Macrauchenia resembled a humpless camel with a short trunk, though it is not closely related to either camels or proboscideans.[1]

History

Macrauchenia appeared in the fossil record some 7 million years ago in South America (in the Miocene epoch). It is likely that Macrauchenia arose from either Theosodon or Promacrauchenia. Notoungulata and Litopterna were two ancient orders of ungulates which only occurred in South America. Many of these species became extinct through competition with invading North American ungulates during the Great American Interchange, after the establishment of the Central American land bridge. A few survivors of this invasion were the litopterns Macrauchenia and Xenorhinotherium and the large notungulates Toxodon and Mixotoxodon. These last original South American hoofed animals died out at the End of the Lujanian (10,000-20,000 years ago)[2] eventually at the time of the arrival of humans at the end of the Pleistocene, along with numerous other large animals on the American continent (such as American elephants, horses, camels, saber-toothed cats and ground sloths). As this genus was the last of the litopterns, its extinction ended that line of mammals.

Anatomy

Macrauchenia had a somewhat camel-like body, with sturdy legs, a long neck and a relatively small head. Its feet, however, more closely resembled those of a modern rhinoceros, and had three hoofs each. It was a relatively large animal, with a body length of around 3 metres (9.8 ft) and a weight up to 1042 kg.[3][4][dead link]

One striking characteristic of Macrauchenia is that, unlike most other mammals, the openings for nostrils on its skull were atop the head, leading some early scientists to believe that, much like a whale, it used these nostrils as a form of snorkel. Soon after some more recent findings[citation needed], this theory was rejected. An alternative theory is that the animal possessed a trunk, perhaps to keep dust out of the nostrils.[3] Macrauchenia's trunk may be comparable to that of the modern Saiga antelope.

One insight into Macrauchenia's habits is that its ankle joints and shin bones may indicate that it was adapted to have unusually good mobility, being able to rapidly change direction when it ran at high speed.[1]

Macrauchenia is known, like its relative, Theosodon, to have had a full set of 44 teeth.

Diet and behavior

Macrauchenia was an herbivore, likely living on leaves from trees or grasses. Carbon isotope analysis of M. patachonica's tooth enamel, as well as analysis of its hypsodonty index (low in this case; i.e., it was brachydont), body size and relative muzzle width suggests that it was a mixed feeder, combining browsing on C3 foliage with grazing on C4 grasses.[5] Scientists believe that, because of the forms of its teeth, Macrauchenia ate using its trunk to grasp leaves and other food. It is also believed that it lived in herds like modern-day wildebeest or antelope, the better to escape predators.

Predators

When Macrauchenia first arose, it would have been preyed upon by the largest of native South American predators, terror birds such as Andalgalornis, and carnivorous sparassodontids such as Thylacosmilus. During the late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene, the Panama Isthmus formed, allowing predators of North American origin, such as the puma, the jaguar and the saber-toothed cat, Smilodon populator, to emigrate into South America and replace the native forms.

It is presumed that Macrauchenia dealt with its predators primarily by outrunning them, or, failing that, kicking them with its long, powerful legs, much like modern-day vicuña or camels[citation needed]. Its potential ability to twist and turn at high speed could have enabled it to evade pursuers.[1]

Fossil evidence

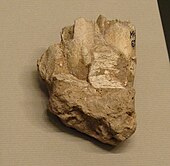

Macrauchenia was first discovered on 9 February 1834 at Port St Julian in Patagonia (Argentina) by Charles Darwin, when HMS Beagle was surveying the port during the voyage of the Beagle.[6] As a non-expert he tentatively identified the leg bones and fragments of spine he found as "some large animal, I fancy a Mastodon". In 1837, soon after the Beagle's return, the anatomist Richard Owen revealed that the bones including vertebrae from the back and neck were actually from a gigantic creature resembling a llama or camel, which Owen named Macrauchenia patachonica.[7] In naming it, Owen noted the original Greek terms Μακρος (large or long), and αυχην (neck) as used by Illiger as the basis of Auchenia as a generic name for the llama, Vicugna and so on.[8] The find was one of the discoveries leading to the inception of Darwin's theory. Since then, more Macrauchenia fossils have been found, mainly in Patagonia, but also in Bolivia, Chile and Venezuela.

Cultural references

Macrauchenia is featured in the episode "Saber-tooth" of the documentary Walking with Beasts, and individuals are featured in the 2002 Blue Sky film Ice Age and its sequels. It was included in the simulation game Zoo Tycoon: Complete Collection as part of the Dinosaur Digs Theme Pack and in Wildlife Park 2: Crazy Zoo as a cloneable beast. The related genus Cramauchenia was named by Florentino Ameghino as a deliberate anagram of Macrauchenia.

References

- ^ a b c "BBC - Science & Nature - Wildfacts - Macrauchenia". Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ^ Alberto L. Cione, Eduardo P. Tonni, Leopoldo Soibelzon: The Broken Zig-Zag: Late Cenozoic large mammal and tortoise extinction in South America. In: Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. 5, 1, 2003, ISSN 1514-5158, S. 1–19, online (PDF; 243 KB)

- ^ a b Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 248. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ^ http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/16838?show=full (in spanish)

- ^ MacFadden, B. J. (Winter, 1997). "Ancient feeding ecology and niche differentiation of Pleistocene mammalian herbivores from Tarija, Bolivia: morphological and isotopic evidence". Paleobiology. 23 (1). Paleontological Society: 77–100. JSTOR 2401158. Retrieved 2011-05-27.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ ed. Keynes, R. D. (2001). "Charles Darwin's Beagle Diary". Cambridge University Press. p. 214. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 238 — Darwin, C. R. to Henslow, J. S., Mar 1834". Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ^ Owen 1838, p. 35

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Barry Cox, Colin Harrison, R.J.G. Savage, and Brian Gardiner. (1999): The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures: A Visual Who's Who of Prehistoric Life. Simon & Schuster.

- Jayne Parsons. (2001): Dinosaur Encyclopedia. DK.

- Haines, Tim & Chambers, Paul. (2006): The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Canada: Firefly Books Ltd.

- Owen, Richard (1838). "Description of Parts of the Skeleton of Macrauchenia patachonica". In Darwin, C. R. (ed.). Fossil Mammalia Part 1 No. 1. The zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. London: Smith Elder and Co.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- An artist's rendition of a Macrauchenia. Retrieved from the Red Académica Uruguaya megafauna page.