Blackfoot Confederacy

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

( ( | |

| Languages | |

| English, Blackfoot | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional beliefs, Sun Dance, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Algonquian peoples |

The Blackfoot Confederacy or Niitsítapi (meaning "original people"[note 1]) is the collective name of three First Nations bands in Alberta, Canada and one Native American tribe in Montana, United States.

Historically, the member peoples of the Confederacy were nomadic bison hunters, who ranged across large areas of the northern Great Plains of Western North America, specifically the semi-arid short-grass prairie ecological region. They later adopted horses and firearms acquired from European-descended traders and their Cree and Assiniboine resellers. With these new tools the Blackfoot expanded their territory at the expense of neighbouring peoples. Through the use of horses, Blackfoot and other Plains peoples harvested bison at a much accelerated rate. However it was the systemic commercial bison hunting by European-American hunters that permanently changed the paradigm of the Great Plains. Periods of starvation and deprivation for the Blackfoot followed. They were then forced to end their nomadism and adopt ranching and farming, settling on small pieces of their former lands. This was the result of treaties with the United States and Canada, mostly signed in the 1870s, which the Blackfoot signed in exchange for food and medical aid and help with farming. Since that time the Blackfoot have worked to maintain their traditional language and culture in the face of past assimilationist policies of the North American nation-states.

Membership

Originally the Blackfoot Confederacy, consisted of three peoples ("nation", "tribes", "tribal nations") based on kin relationships and dialect, but all speaking a common language, the Blackfoot language. These were the Piikáni (historically called "Piegan Blackfeet" in English-language sources), the Káínaa (called "Bloods"), and the Siksikáwa ("Blackfoot"). They later allied with the unrelated Tsuu T'ina ("Sarcee") who became merged into the Confederacy and, (for a time) with Atsina ("Gros Ventres"). Each of these peoples were divided into many bands which ranged in size from 10 to 30 lodges, or about 80 to 240 persons, and it was the band, rather than the tribe, which was the basic unit of organization for hunting and defence.[1]

The largest ethnic group in the Confederacy is the Piegan, Peigan or Pikuni. Their name derives from the Blackfoot term Piikáni. They are divided into the North Peigan (Aapátohsipikáni or simply Piikáni) in Alberta, and the South Peigan or Piegan Blackfeet (Aamsskáápipikani) in Montana. A further once large and mighty division of the Piegan were the Inuk'sik (I-nuks'-iks or Inuck'siks - ″Small Robes″)[2] of southwestern Montana which today only survive as a clan or band of the South Peigan.

The modern Kainai Nation is named for the Blackfoot language term Káínaa, meaning "Many Chief people". There were historically also called the Blood from a Plains Cree name for the Kainai: Miko-Ew, meaning "stained with blood" (i.e. "the bloodthirsty, cruel") therefore, the common English name for the tribe is Blood or the Blood tribe.

The Siksika Nation's name derives from Siksikáwa meaning "black foot people". The Siksika also call themselves Sao-kitapiiksi meaning "Plains People".[3]

The Sarcee call themselves the Tsu T’ina meaning "a great number of people", but were called saahsi or sarsi, "the stubborn ones", by the Blackfoot during their early years of conflict. The Sarcee are from an entirely different language family from the other Plains peoples, they are part of the Athabascan or Dene language family, most of whose members are located in Subartic of Northern Canada. The Sarcee are specifically an offshoot of the Beaver (Danezaa) people who migrated south onto the plains sometime in the early eighteenth century. They later joined the Confederacy and essentially merged with the Pikuni.

The Gros Ventre people call themselves the Haaninin ("white clay people") and were called the Fall Indians or Gros Ventres (from French for "fat bellies") in English, and Piik-siik-sii-naa ("snakes") or Atsina ("like a Cree") in Blackfoot. Early scholars thought they were related to the Arapaho Nation, who inhabited the Missouri Plains and moved west to Colorado and Wyoming.[4] They were allied with the Confederacy from circa 1793 to 1861, and enemies of it thereafter.

The Confederacy used to hunt and forage on both sides of the current Canada–US border. But both governments forced them to end their nomadic traditions and settle on "Indian reserves" (Canadian terminology) or "Indian reservations" (US terminology) during the late nineteenth century. Excluding the Gros Ventre (who no longer counted as members), the South Peigan are the only group that chose to settle in Montana, and the other three Blackfoot-speaking peoples and the Sarcee are located in Alberta. Together, the Blackfoot-speakers call themselves the Niitsítapi (the "Original People").

When these peoples were forced to end their nomadic traditions because of the demise of the American bison herds and the division of their territory between Canada and the United States, their social structures changed. Tribal nations, which had formerly been mostly ethnic associations, were institutionalized as governments (referred to as "tribes" in the United States and "bands" or "First Nations" in Canada). The Piegan were divided in the North Peigan in Alberta, and the South Peigan in Montana.

History

| Type | Confederacy |

|---|---|

| Membership | North Peigan, South Peigan, Kainai, Siksika Later: Sarcee, Gros Ventres |

The Confederacy had[when?] a territory that stretched from the North Saskatchewan River (called Ponoká'sisaahta)[dubious – discuss] along what is now Edmonton, Alberta, in Canada, to the Yellowstone River (called Otahkoiitahtayi) of Montana in the United States, and from the Rocky Mountains (called Miistakistsi) and along the South Saskatchewan River to the present Alberta-Saskatchewan border (called Kaayihkimikoyi),[5] east past the Cypress Hills. They called their tribal territory Nitawahsin-nanni- "Our Land", an obvious similarity with Nitassinan - "Our Land", the name for the homeland of the Innu and Naskapi to the east.[6] They had adopted the use of the horse from other Plains tribes probably by the early eighteenth century, which gave them expanded range and mobility, as well as advantages in hunting.

The basic social unit of the Niitsitapi above the family was the band, varying from about 10 to 30 lodges, about 80 to 241 people. (European Canadians and Americans mistakenly referred to all the Niitsitapi nations as "Blackfoot", but only one nation was called Siksika or Blackfoot.) This size group was large enough to defend against attack and to undertake small communal hunts, but was also small enough for flexibility. Each band consisted of a respected leader, possibly his brothers and parents, and others who were not related. Since the band was defined by place of residence, rather than by kinship, a person was free to leave one band and join another, which tended to ameliorate leadership disputes. As well, should a band fall upon hard times, its members could split up and join other bands. In practice, bands were constantly forming and breaking up. The system maximized flexibility and was an ideal organization for a hunting people on the northwestern Great Plains.

During the summer, the people assembled for nation gatherings. In these large assemblies, warrior societies played an important role for the men. Membership into these societies was based on brave acts and deeds.

For almost half the year in the long northern winter, the Niitsitapi lived in their winter camps along a wooded river valley. They were located perhaps a day's march apart, not moving camp unless food for the people and horses, or firewood became depleted. Where there was adequate wood and game resources, some bands would camp together. During this part of the year, buffalo wintered in wooded areas where they were partially sheltered from storms and snow. They were easier prey as their movements were hampered. In spring the buffalo moved out onto the grasslands to forage on new spring growth. The Blackfoot did not follow immediately, for fear of late blizzards. As dried food or game became depleted, the bands would split up and begin to hunt the buffalo.

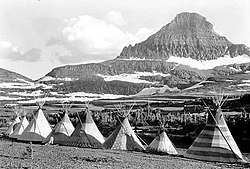

In midsummer, when the chokecherries ripened, the people regrouped for their major ceremony, the Okan (Sun Dance). This was the only time of year when the four nations would assemble. The gathering reinforced the bonds among the various groups and linked individuals with the nations. Communal buffalo hunts provided food for the people, as well as offerings of the bulls' tongues (a delicacy) for the ceremonies. These ceremonies are sacred to the people. After the Okan, the people again separated to follow the buffalo. They used the buffalo hides to make their dwellings and temporary tipis.

In the fall, the people would gradually shift to their wintering areas. The men would prepare the buffalo jumps and pounds for capturing or driving the bison for hunting. Several groups of people might join together at particularly good sites, such as Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. As the buffalo were naturally driven into the area by the gradual late summer drying off of the open grasslands, the Blackfoot would carry out great communal buffalo kills.

The women processed the buffalo, preparing dried meat, and combining it for nutrition and flavor with dried fruits into pemmican to last them through winter and other times when hunting was poor. At the end of the fall, the Blackfoot would move to their winter camps. The women worked the buffalo and other game skins for clothing, as well as to reinforce their dwellings; other elements were used to make warm fur robes, leggings, cords and other needed items. Animal sinews were used to tie arrow points and lances to throwing sticks, or for bridles for horses.

The Niitsitapi maintained this traditional way of life based on hunting bison, until the near extirpation of the bison by 1881 forced them to adapt their ways of life in response to the effects of the European settlers and their descendants. In the United States, they were restricted to land assigned in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 and were later given a distinct reservation in the Sweetgrass Hills Treaty of 1887. In 1877, the Canadian Niitsitapi signed Treaty 7 and settled on reserves in southern Alberta.

This began a period of great struggle and economic hardship; the Niitsitapi had to try to adapt to a completely new way of life. They suffered a high rate of fatalities when exposed to Eurasian diseases, for which they had no natural immunity.

Eventually, they established a viable economy based on farming, ranching, and light industry. Their population has increased to about 16,000 in Canada and 15,000 in the U.S. today. With their new economic stability, the Niitsitapi have been free to adapt their culture and traditions to their new circumstances, renewing their connection to their ancient roots.

Early history

The Niitsitapi, also known as the Blackfoot Indians, reside in the Great Plains of Montana and the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.[7] Only one of the Niitsitapi are called Blackfoot or Siksika. The name is said to have come from the color of the peoples’ moccasins, made of leather. They had typically dyed or painted the soles of their moccasins black. One legendary story claimed that the Siksika walked through ashes of prairie fires, which in turn colored the bottoms of their moccasins black.[7] Anthropologists believe the Niitsitapi had not originated in the Great Plains of the Midwest North America, but rather migrated from the upper Northeastern part of the country.

Due to language and cultural patterns, anthropologists believe that the Blackfoot originally coalesced as a group whilst living in the forests of what is now the Northeastern United States. They were mostly located around the modern-day border between Canada and the state of Maine. By 1200, the Niitsitapi had decided to relocate in search of more land.[citation needed] They moved west and settled for a while north of the Great Lakes in present-day Canada, but had to compete with existing tribes. They decided to leave the Great Lakes area and keep moving west.[8]

When they moved, they usually packed their belongings on an A-shaped sled called a travois. The travois was designed for transport over dry land.[9] The Blackfoot had relied on dogs to pull the travois, since they did not acquire horses until the 18th century. From the Great Lakes area, they continued to move west and eventually settled in the Great Plains.

The Plains had covered approximately 780,000 square miles (2,000,000 km2) with the Saskatchewan River to the north, the Rio Grande to the south, the Mississippi River to the east, and the Rocky Mountains to the west.[10] Adopting the use of the horse, the Niitsitapi established themselves as one of the most powerful Indian tribes on the Plains in the late 18th century, earning themselves the name "The Lords of the Plains."[11] Niitsitapi stories trace their residence and possession of their plains territory to "time immemorial."

Importance and uses of buffalo

While the Niitsitapi were in the Great Plains, they came to depend as their main source of food on the American bison (buffalo), which is the largest mammal in North America, standing about 6+1⁄2 feet (2.0 m) tall and weighing up to 2,000 pounds (910 kg).[12] Before the introduction of horses, the Niitsitapi had to devise ways to get close to buffalo unnoticed so they could get in range for a good shot. The first and most common way for them to hunt the buffalo was using the buffalo jump. The hunters would round up the buffalo into V-shaped pens and drive them over a cliff (they hunted pronghorn antelopes in the same way). After the buffalo went over the cliff, the Indians would go to the bottom and take as much meat as they needed and could carry back to camp. They also used camouflage for hunting.[12] The hunters would take buffalo skins from previous hunting trips and drape them over their bodies to blend in and mask their scent. By subtle moves, the hunters could get close to the herd. When close enough, the hunters would attack with arrows, or use lances and spears to finish off wounded animals.

The people used virtually all parts of the body and skin. The women prepared the meat for food: by boiling, roasting and drying for jerky. This processed it to last a long time without spoiling, and they depended on bison meat to get through the winters.[13] The winters were long, harsh, and cold due to the lack of trees in the Plains, so the people stockpiled the meat when they had the chance.[14] The hunters often ate the bison heart minutes after the kill, as part of their hunting ritual. The women tanned and prepared the skins to cover the tepees. These were made of log poles, with the skins draped over it. The tepee remained warm in the winter and cool in the summer, and was a great shield against the wind.[15]

With further preparation by tanning and softening, the women made special clothing from the skins: robes and moccasins. They rendered bison fat to make soap. Both men and women made utensils, sewing needles and tools from the bones, using tendon for fastening and binding. The stomach and bladder were cleaned and prepared for use as containers for storing liquids. Dried bison dung was fuel for the fires. The Niitsitapi considered the animal sacred, integral to their lives.[16]

Discovery and uses of horses

Up until around 1730, the Blackfoot traveled by foot and used dogs to carry and pull some of their goods. They had not seen horses in their previous lands, but were introduced to them on the Plains, as other tribes, such as the Shoshone, had already adopted their use.[17] They saw the advantages of horses and wanted some. The Blackfoot called the horses ponokamita (elk dogs).[18] The horses could carry much more weight than dogs and moved at a greater speed. They could be ridden for hunting and travel.[19]

Horses revolutionised life on the Great Plains and soon came to be regarded as a measure of wealth. Warriors regularly raided other tribes for their best horses. Horses were generally used as universal standards of barter. Medicine men were paid for cures and healing with horses. Those who designed shields or war bonnets were also paid in horses.[20] The men gave horses to those who were owed gifts as well as to the needy. An individual’s wealth rose with the number of horses accumulated, but a man did not keep an abundance of them. The individual’s prestige and status was judged by the number of horses that he could give away. For the Indians who lived on the Plains, the principal value of property was to share it with others.[21]

After having driven the hostile Shoshone and Arapaho from the Northwestern Plains, the Niitsitapi began in 1800 a long phase of keen competition in the fur trade with their former Cree allies, which often escalated militarily. In addition that both groups had begun about 1730 a life on horseback, and thus around mid-century an adequate supply of horses became a question of survival. Horse theft was at this stage not only a proof of courage, but often a desperate contribution to survival, for many ethnic groups competed for hunting in the grasslands.

Under the lasting attacks and horse raiding expeditions by the Cree and Assiniboine had particularly to suffer the horse-rich Niitsitapi allies, the Gros Ventre (in Cree: Pawistiko Iyiniwak - "Rapids People" - "People of the Rapids", also known as Niya Wati Inew, Naywattamee - "They Live in Holes People"), because their tribal lands were along the Saskatchewan River Forks (the confluence of North and South Saskatchewan River) and had first to withstand the attacks by their enemies, armed with guns. In retaliation for supplying their enemies with weapons the Gros Ventre attacked and burned in 1793 South Branch House of the Hudson's Bay Company on the South Saskatchewan River near the present village of St. Louis, Saskatchewan. Then, the tribe moved southward to the Milk River in Montana and allied themselves with the Blackfoot. The area between the North Saskatchewan River and Battle River (the name derives from the war fought between these two tribal groupings) was the limit of the now warring tribal alliances.[22]

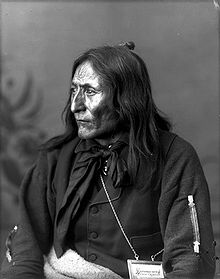

Enemies & Warrior Culture

Blackfoot war parties would ride hundreds of miles on raids. A boy on his first war party was given a silly or derogatory name. But after he had stolen his first horse or killed an enemy, he was given a name to honor him. Warriors would strive to perform various acts of bravery called counting coup, in order to move up in social rank. The coups in order of importance were: taking a gun from a living enemy and or touching him directly; capturing lances, and bows; scalping an enemy; killing an enemy; freeing a tied horse from in front of an enemy lodge; leading a war party; scouting for a war party; stealing headdresses, shields, pipes (sacred ceremonial pipes); and driving a herd of stolen horses back to camp.[23]

The Niitsitapi were enemies of the Crow, Cheyenne (kiihtsipimiitapi - ″Pinto People″), and Sioux (Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota) (called pinaapisinaa - “East Cree”) on the Great Plains; and the Shoshone, Flathead, Kalispel, Kootenai (called kotonáá'wa) and Nez Perce (called komonóítapiikoan) in the mountain country to their west and southwest. Their most mighty and most dangerous enemy, however, were the political/military/trading alliance of the Iron Confederacy or Nehiyaw-Pwat (in Plains Cree: Nehiyaw - ‘Cree’ and Pwat or Pwat-sak - ‘Sioux, i.e. Assiniboine’) - named after the dominating Plains Cree (called Asinaa) and Assiniboine (called Niitsísinaa - “Original Cree”), including Stoney (called Saahsáísso'kitaki or Sahsi-sokitaki - ″Sarcee trying to cut″),[24] Saulteaux (or Plains Ojibwe) and Métis to the north, east and southeast. With the expansion of the Nehiyaw-Pwat to the north, west and southwest, they integrated larger groups of Iroquois, Chipewyan, Danezaa (Dunneza - 'The real (prototypical) people'),[25] Ktunaxa, Flathead, and later Gros Ventre (called atsíína - “Gut People” or “like a Cree”), in their local groups. Loosely allied with the Nehiyaw-Pwat, but politically independent, were neighboring tribes like the Ktunaxa, Secwepemc and in particular the arch enemy of the Blackfoot, the Crow, or Indian trading partners like the Nez Perce and Flathead.[26]

The Shoshone got horses much sooner than the Blackfoot and soon occupied much of present-day Alberta, most of Montana, and parts of Wyoming, and raided the Blackfoot frequently. Once the Piegan, in particular, had access to horses of their own and guns obtained from the HBC via the Cree and Assiniboine, the situation changed, however. By 1787 David Thompson reports that the Blackfoot had completely conquered most of Shoshone territory, and frequently captured Shoshone women and children and forcibly assimilated them into Blackfoot society, further increasing their advantages over the Shoshone. Thompson reports that Blackfoot territory in 1787 was from the North Saskatchewan River in the north to the Missouri River in the South, and from Rocky Mountains in the west out to a distance of 300 miles (480 km) to the east.[27]

Between 1790 and 1850 the Nehiyaw-Pwat were at the height of their power - they could successfully defend their territories against the Sioux (Lakota, Nakota and Dakota) and the Niitsitapi Confederacy. During the so-called Buffalo Wars (about 1850 - 1870) they penetrated further and further into the territory from the Niitsitapi Confederacy in search for the buffalo, so that the Piegan were forced to evade in the region of the Missouri River (in Cree: Pikano Sipi - "Muddy River", "Muddy, turbid River"), the Kainai withdrew to the Bow River and Belly River, only the Siksika could hold their tribal lands along the Red Deer River. Around 1870, the alliance between the Blackfoot and the Gros Ventre broke, and the latter had to look at their former enemies, the Southern Assiniboine (or Plains Assiniboine), for protection.

First contact with Europeans and the Fur Trade

Anthony Henday of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) met a large Blackfoot group in 1754 in what is now Alberta. The Blackfeet had established dealings with traders connected to the Canadian and English fur trade before meeting the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1806.[28] Lewis and Clark and their men had embarked on mapping the Missouri River for the United States government. On their return trip, Lewis and three of his men encountered a group of young Blackfeet warriors with a large herd of horses, and it was clear to Meriwether Lewis that they were not far from much larger groups of warriors. Lewis explained to them that the United States government wanted peace with all Indian nations,[29] and explained that they had successfully formed alliances with other Indian nations.[28] The group camped together that night, and at dawn there was a scuffle as it was discovered that the Blackfeet were attempting to steal guns and run off with their horses while the men slept. In the ensuing struggle, one warrior was fatally stabbed and another shot by Lewis and presumed killed.[30]

In subsequent years, American mountain men trapping in Blackfoot country generally encountered hostility. When one member of the Lewis and Clark expedition, John Colter, returned to Blackfoot country soon after, he barely escaped with his life. In 1809, Colter and his companion were trapping on the Jefferson river by canoe when they were surrounded by hundreds of Blackfeet warriors on horseback on both sides of the river bank. Colter's companion, John Potts, did not surrender and was killed. Colter was stripped of his clothes and then forced to run for his life, after being given a head start (famously known in the annals of the West as "Colter's Run", he eventually escaped by reaching a river five miles away and then diving under either an island of driftwood or a beaver dam, where he remained concealed until after nightfall, after which he trekked 300 miles to a fort).[31][32]

In the context of shifting tribal politics due to the spread of horses and guns, the Niitsitapi initially tried to increase their trade with the HBC traders in Rupert's Land whilst blocking access to the HBC by neighboring peoples to the West, however the HBC trade eventually reached into what is now inland British Columbia. "By the late 1820s, [this prompted] the Niitsitapiksi, and in particular the Piikani, whose territory was rich in beaver, [to] temporarily put aside cultural prohibitions and environmental constraints to trap enormous numbers of these animals and, in turn, receive greater quantities of trade items".[33]

The HBC encouraged Niitsitapiksi to trade with posts on the North Saskatchewan River, on the northern boundary of their territory. In 1830s the Rocky Mountain region and the wider Saskatchewan District were the HBC's most profitable and Rocky Mountain House was the HBC's busiest post and was primarily used by the Piikani. Other Niitsitapiksi nations traded more in pemmican and buffalo skins than beavers, and visited other posts such as Fort Edmonton[34]

Meanwhile in 1822 the American Fur Company entered the Upper Missouri region from the south for the first time, without Niitsitapiksi permission, leading to tensions and conflict, until 1830 when peaceful trade was established. This followed by the opening of Fort Piegan as the first American trading post in Niitsitapi territory in 1831, joined by Fort MacKenzie in 1833. The Americans offered better terms of trade and were more interested in buffalo skins than the HBC, which brought more trade from the Niitsitapi. The HBC responded by building Bow Fort (Peigan Post) on the Bow River in 1832, but it was not a success.[35]

In 1833, German explorer Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied and Swiss painter Karl Bodmer spent months with them to get a sense of their culture. Bodmer portrayed their society in paintings and drawings.[30]

Contact with the Europeans caused a spread of infectious diseases to the Niitsitapi, mostly cholera and smallpox.[36] In one instance in 1837, an American Fur Company steamboat, the St. Peter's, was headed to Fort Union and several passengers contracted smallpox on the way. They continued to send a smaller vessel with supplies farther up the river to posts among the Niitsitapi. The Niitsitapi contracted the disease and eventually 6,000 died, marking an end to their dominance among tribes over the Plains. The Hudson’s Bay Company did not require or help their employees get vaccinated; the English doctor Edward Jenner had developed a technique 41 years before but its use was not yet widespread.[37]

The Indian Wars

Like many other Great Plains Indian nations, the relationship with white settlers was often hostile. Despite the hostilities the Blackfeet stayed largely out of the Great Plains Indian Wars, neither fighting against or scouting for the United States army with the exception of the Marias Massacre on January 23, 1870. A combination of friendly relationships with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Marias Massacre discouraged the Blackfeet from engaging in wars against Canada and the United States. While fighting the United States army alongside their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies, the Lakota sent runners into Blackfeet territory, urging them to join the fight. Crowfoot, one of the most influential Blackfeet chiefs dismissed the Lakota messengers and threatened to fight them alongside the NWMP if they entered north into Blackfeet country again. News of Crowfoot's loyalty reached Ottawa and from there London where Queen Victoria praised Crowfoot and the Blackfeet for their loyalty.[38] Despite his threats, Crowfoot latter met the Lakota who under the guidance of Sitting Bull fled to Canada after defeating George Armstrong Custer and his battalion at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Crowfoot saw the Lakota as refugees and was sympathetic to their strife but retained his anti-war stance. Sitting Bull and Crowfoot fostered peace between the two nations by a ceremonial offering of tobacco, ending hostilities between them. Sitting Bull was so impressed by Crowfoot that he named one of his sons after him.[39]

The Blackfeet also chose to stay out of the Northwest Rebellion, led by the famous Métis leader Louis Riel. Louis Riel and his men added to the already unsettled conditions facing the Blackfeet by camping near them, attempting to spread discontent with the government and thus gain a powerful ally. The Northwest Rebellion was made up mostly of Métis, Assiniboine (Nakota) and Plains Cree who all fought for reasons very similar to what was causing the Blackfeet hardship, including the destruction of Bison herds. The Plains Cree were one of the Blackfeet's most hated enemies, however peace was made between the two nations when Crowfoot adopted the influential Cree Chief and great peacemaker Poundmaker as his son. Despite not fighting, Crowfoot's sympathy was largely with the rebellion, especially the Cree under the influence of such famous chiefs as Poundmaker, Big Bear, Wandering Spirit and Fine-Day. When news of continued Blackfeet neutrality reached Ottawa, Lord Lansdowne, the governor general, expressed his thanks to Crowfoot once again on behalf of the Queen back in London. The cabinet of Sir John A. Macdonald (the current Prime Minister of Canada at the time) gave Crowfoot a round of applause.[40]

Marias Massacre

The Marias Massacre was a major massacre of around 200 people from the Piegan nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy by United States Army troops along the Marias River that took place on January 23, 1870.

Relations between the Blackfoot and Euro-American settlers at the time of the event were largely hostile verging on a war between the United States and the Blackfoot Confederacy. Events leading up to the massacre largely revolved around a young Piegan warrior named Owl Child who stole a herd of horses from an American trader named Malcolm Clark. Clark retaliated by tracking Owl Child down and severely beating him in full view of Owl Child's camp. Malcolm Clarke also raped a Blackfoot woman, the relative of his wife who was also a Blackfoot woman. Clarke's rape victim was Owl Child's wife.[41] The raped woman gave birth to a child as a result of the rape.[42] Clark was later killed by a group of young warriors including Owl Child seeking revenge for his humiliation. Public outcry from news of the event led to General Philip Sheridan dispatching a band of cavalry led by Major Eugene Baker to find Owl Child and his camp.

On January 23, 1870, a camp of Piegan Indians were spotted by army scouts and reported to the dispatched cavalry, wrongly being claimed to be led by chief Mountain Chief. Around 200 soldiers surrounded the camp the following morning and prepared for an ambush. Before the command to fire the chief of the surrounded camp named Heavy Runner noticed the crouching soldiers on the snowy bluffs above the encampment and signaled to them showing his safe-conduct paper. Heavy Runner and his band of Piegans shared peace between American settlers and troops at the time of the event. Heavy Runner was shot and killed by an army scout named Joe Cobell despite warnings by fellow scout Joe Kipp who was threatened by the cavalry for reporting the camp was home to a friendly band of Piegans and not led by Mountain Chief.[43]

Following the death of Heavy Runner the camp was attacked by the hiding soldiers resulting in the deaths of 173 Piegans and 1 U.S Army soldier who fell of his horse. Most of the victims were women, children and the elderly due to most of the men including the warriors being out hunting. The number of Piegans taken prisoner was 140, the captured people were soon turned loose without proper clothing resulting in many additional deaths from exposure as they traveled as refugees to Fort Benton.

The greatest slaughter of Indians ever made by U.S. Troops

— -Lieutenant Gus Doane, commander of F Company

Following the massacre was a brief outcry by the United States congress and press in the east of the country. General William Sherman outright denied any guilt and reported that most of the killed were warriors under Mountain Chief. An official investigation never occurred and no monument marks the spot of the massacre. Unlike most Indian massacres in the United States such as Wounded Knee and Sand Creek the Marias Massacre remains largely unknown.

Hardships of the Niitsitapi

During the mid-1800s, the Niitsitapi faced a dwindling food supply, as European-American hunters were taking too many bison, and settlers were encroaching on their territory. Without the buffalo, the Niitsitapi could not hunt enough food and were forced to depend on the United States government for supplies.[44] In 1855, the Niitsitapi chief Lame Bull made a peace treaty with the United States government. The Lame Bull Treaty promised the Niitsitapi $20,000 annually in goods and services in exchange for their moving onto a reservation.[45]

In 1860, very few buffalo were left, and the Niitsitapi became completely dependent on their government supplies. Often the food was spoiled by the time they received it. Hungry and desperate, Blackfoot raided white settlements for food and supplies and caused a stir with the United States Army. In January 1870, the army attacked a peaceful Niitsitapi village, killing 173 and leaving only 46 survivors.

The Cree and Assiniboine lived just like the Blackfoot by the dwindling herds of the buffalo and their hunters followed their prey, which was about 1850 found almost exclusively on the territory of the Blackfoot. Therefore in 1870 various Nehiyaw-Pwat bands began a final effort to get hold of their prey, by beginning a war. They hoped to defeat the Blackfoot weakened by smallpox and attacked a camp near Fort Whoop-Up (called Akaisakoyi - “Many Dead”). But they were defeated in the so-called Battle of the Belly River (near Lethbridge, called Assini-etomochi – "where we slaughtered the Cree") and lost over 300 warriors. The next winter the hunger compelled them to negotiate with the Niitsitapi, with whom they made a final lasting peace.

The winter of 1883–1884 became known as “Starvation Winter” because no government supplies came in, and the buffalo were gone. That winter, 600 Niitsitapi died of hunger.[46]

The United States passed laws that adversely affected the Niitsitapi. In 1874, the US Congress voted to change the Niitsitapi reservation borders without discussing it with the Niitsitapi. They received no other land or compensation for the land lost, and in response, the Kainai, Siksika, and Piegan moved to Canada; only the Pikuni remained in Montana.[47]

In efforts to assimilate the Native Americans to European-American ways, in 1898, the government dismantled tribal governments and outlawed the practice of traditional Indian religions. They required Blackfoot children to go to boarding schools, where they were forbidden to speak their native language, practise customs, or wear traditional clothing.[48] In 1907, the United States government adopted a policy of allotment of reservation land to individual heads of families to encourage family farming and break up the communal tribal lands. Each household received a 160-acre (65 ha) farm, and the government declared the remainder "surplus" to the tribe's needs. It put it up for sale for development.[48] The allotments were too small to support farming on the arid plains. A 1919 drought destroyed crops and increased the cost of beef. Many Indians were forced to sell their allotted land and pay taxes which the government said they owed.[49]

In 1934 the Indian Reorganization Act, passed by the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, ended allotments and allowed the tribes to choose their own government. They were also allowed to practise their cultures.[49] In 1935, the Blackfoot Nation of Montana began a Tribal Business Council. After that, they wrote and passed their own Constitution, with an elected representative government.[50]

The Blackfoot Nation

The Blackfoot Nation is made up of four nations. These nations include the Piegan, Siksika, Northern Piegan, and Kainai or Blood Indians.[17] The four nations come together to make up what is known as the Blackfoot Confederacy, meaning that they have banded together to help one another. The nations have their own separate governments ruled by a head chief, but regularly come together for religious and social celebrations. Today the only nation that resides within US boundaries in Montana is the Piegan, or Pikuni.[19]

Culture

Electing a leader

Family was highly valued by the Blackfoot Indians. For traveling, they also split into bands of 20-30 people, but would come together for times of celebration.[51] They valued leadership skills and chose the chiefs who would run their settlements wisely. During times of peace, the people would elect a peace chief, meaning someone who could lead the people and improve relations with other tribes. The title of war chief could not be gained through election and needed to be earned by successfully performing various acts of bravery including touching a living enemy.[52] Blackfoot bands often had minor chiefs in addition to an appointed head chief.

Societies

Within the Blackfoot Nation, there were different societies to which people belonged, each of which had functions for the tribe. Young people were invited into societies after proving themselves by recognized passages and rituals. For instance, young men had to perform a vision quest, begun by a spiritual cleansing in a sweat lodge.[53] They went to gather buffalo chips and set out from the camp alone for four days of fasting and praying. Their main goal was to see a vision that would explain their future. After having the vision, a youth returned to the village ready to join society.

In a warrior society, the men had to be prepared for battle. Again, the warriors would prepare by spiritual cleansing, then paint themselves symbolically; they often painted their horses for war as well. Leaders of the warrior society carried spears or lances called a coup stick, which was decorated with feathers, skin, and other tokens. They won prestige by "counting coup", tapping the enemy with the stick and getting away.

Members of the religious society protected sacred Blackfoot items and conducted religious ceremonies. They blessed the warriors before battle. Their major ceremony was the Sun Dance, or Medicine Lodge Ceremony. By engaging in the Sun Dance, their prayers would be carried up to the Creator, who would bless them with well-being and abundance of buffalo.

Women’s societies also had important responsibilities for the communal tribe. They designed refined quillwork on clothing and ceremonial shields, helped prepare for battle, prepared skins and cloth to make clothing, cared for the children and taught them tribal ways, skinned and tanned the leathers used for clothing and other purposes, prepared fresh and dried foods, and performed ceremonies to help hunters in their journeys.[54]

Use of Sweet Grass and Sage

Sage and sweet grass is often used by the Blackfoot and other plains nations for a number of ceremonial purposes and is considered a sacred plant. Sage and sweet grass is burned with the user inhaling and covering themselves in the smoke in a process known widely as smudging. Sage is said to rid the body of negative emotions such as anger. Sweet grass is said to draw in positive energy. Both are used for purification purposes.The pleasant and natural odor of the burning grass is said to attract spirits. Sweet grass is prepared for ceremony by braiding the stems together then drying them before burning.

Sweet grass is also often present and burned in pipe-smoking mixtures alongside bearberry and red willow plants. The smoke from the pipe is said to carry the users prayers up to the creator with the rising smoke. Large medicine bags often decorated with ornate beaded designs were used by medicine men to carry sage, sweet grass, and other important plants.[55]

Marriage

In the Blackfoot culture, men were responsible for choosing their marriage partners, but women had the choice to accept them or not. The male had to show the woman’s father his skills as a hunter or warrior. If the father was impressed and approved of the marriage, the man and woman would exchange gifts of horses and clothing and were considered married. The married couple would reside in their own tipi or with the husband’s family. Although the man was permitted more than one wife, typically he only chose one. In cases of more than one wife, quite often the male would choose a sister of the wife, believing that sisters would not argue as much as total strangers.[56]

Responsibilities and clothing

In a typical Blackfoot family, the father would go out and hunt and bring back supplies that the family might need. The mother would stay close to home and watch over the children while the father was out. The children were taught basic survival skills and culture as they grew up. It was generally said that both boys and girls learned to ride horses early. Boys would usually play with toy bows and arrows until they were old enough to learn how to hunt.[52]

They would also play a popular game called shinny, which later became known as ice hockey. They used a long curved wooden stick to knock a ball, made of baked clay covered with buckskin, over a goal line. Girls were given a doll to play with, which also doubled as a learning tool because it was fashioned with typical tribal clothing and designs and also taught the young women how to care for a child.[57] As they grew older, more responsibilities were placed upon their shoulders. The girls were then taught to cook, prepare hides for leather, and gather wild plants and berries. The boys were held accountable for going out with their father to prepare food by means of hunting.[58]

Typically clothing was made primarily of softened and tanned antelope and deer hides. The women would make and decorate the clothes for everyone in the tribe. Men wore moccasins, long leggings that went up to their hips, a loincloth, and a belt. Occasionally they would wear shirts but generally they would wrap buffalo robes around their shoulders. The distinguished men of bravery would wear a necklace made of grizzly bear claws.[58]

Boys dressed much like the older males, wearing leggings, loincloths, moccasins, and occasionally an undecorated shirt. They kept warm by wearing a buffalo robe over their shoulders or over their heads if it became cold. Women and girls wore frocks made from two or three deerskins. The women liked to wear earrings and bracelets made from sea shells which they traded for, or different types of metal. They would sometimes wear beads in their hair or paint the part in their hair red, which signified that they could still have children.[58]

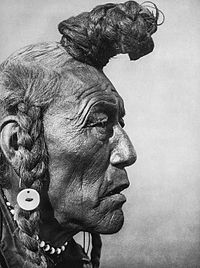

Headdresses

Like all other Indian nations that lived on the plains the Blackfeet wore a variety of different headdresses which served different purposes as well as had different meanings and associations. The typical eagle feathered war bonnet was popular among prestigious warriors and chiefs (including war-chiefs) of the Blackfeet. The straight-up headdress is a uniquely Blackfeet headdress that, like the war bonnet, is made with eagle feathers. However unlike traditional war bonnets, the feathers on the straight-up headdress point directly straight upwards from the rim (hence the name). Often a red plume is attached to the front of the headdress, it too points straight upwards.

The split horn headdress was very popular among northern plains Indian nations, particularly those of the Blackfeet Confederacy. Many warrior societies including the Horn Society of the Blackfeet wore the split horn headdress. The split horn headdress was made from a single bison horn which was split into two halves, reshaped into two a slimmer versions of a full sized bison horn, and then polished. The two half horns were then attached to a beaded rimmed felt hat. The furs from weasels in their winter coats were attached to the top of the headdress as well as dangled down the sides. The furs dangling down the sides of the headdress often had bead work at the ends attached to the headdress. A similar headdress called the antelope horn headdress looked and was made in a similar fashion using the horn or horns from a pronghorn antelope.

Blackfeet men, particularly warriors sometimes wore a roach made from porcupine hair. The hairs of the porcupine are most often dyed red. Eagle and or other bird feathers were occasionally attached to the roach.

Buffalo scalps, often with horns still attached and often with a beaded rim, were also worn. Fur "turbans" made from soft animal fur (most often otter) were also popular. Buffalo scalps and fur turbans were worn most often in the winter to protect the head area from cold weather.

All of the headdresses worn by the Blackfeet in the past are still worn today, especially by elected chiefs, members of various traditional societies (including the horn, Crazy Dog and Motokik Societies), powwow dancers and spiritual leaders.[59]

The Sun and the Moon

One of the most famous traditions held by the Blackfoot would be their story of sun and the moon. It starts out with a man, wife, and two sons. The family has no bows and arrows or any way to get food, so they lived off berries. The man had a dream and he was told by the Creator Napi, Napiu, or Napioa (depending on the band) to get a large spider web and put it on the trail the animals roamed, and they would get caught up and could be easily killed with the stone axe he had. The man had done so and saw that it was true. One day, he came home from bringing in some fresh meat from the trail and discovered his wife to be applying perfume on herself. He thought that she must have another lover since she never did that for him. He then told his wife that he was going to move a web and asked if she could bring in the meat and wood. She had reluctantly gone out, just past his sight to check if he was watching, and then took off. The father then asked his children where she acquired the wood from but they did not know. The man set out and found the timber and also a den of rattlesnakes, one of which being his wife’s lover. He had set the timber on fire and knew his wife would come back and try to kill his family. He told the children to flee and gave them a stick, stone, and moss to use if their mother chased after them. He remained at the house and put a web over his front door. The wife tried to get in but got her leg caught, and at once the man cut her leg off. She then put her head through and he cut that off also. The father and boys went in opposite ways, but the head followed the children and the body followed the man. The oldest boy saw the head and threw the stick, and where it landed, a forest popped up. The head made it through, so the younger brother was instructed to throw the stone. He did so, and where the stone landed a huge mountain popped up. It spanned from big water (ocean) to big water and the head was forced to go through it, not around. The head met up with some rams and said to them she would marry their chief if they butted their way through the mountain. The chief cleared it and they butted until their horns were worn down, but still was not through. She then asked the ants if they could burrow through the mountain with the same stipulations and it was agreed and they get her the rest of the way through. The children were far ahead and wet the moss. Soon after they did that, they saw the head and threw the moss down, and suddenly they were in a different land. They were surrounded by water, and the head rolled in and drowned. They decided to build a raft and head back, and once they returned to their land, they discovered that it was occupied. They then decided to split up. One brother was simple and went north to discover what he could and make people. The other was shrewd and went south to make white people and taught them valuable skills. The simple brother began the Blackfoot. He became known as Left Hand and later by the Blackfoot as Old Man. The woman’s body still chases the man, she is the moon and he is the sun, and if she is to ever catch him, it will always be night.[60]

Blackfoot creation myth

The creation myth is another commonly shared piece of oral history among the Blackfoot Nation. It was said that in the beginning, Napi floated on a log with four animals. The animals were: Mameo (fish), Matcekups (frog), Maniskeo (lizard), and Sopeo (turtle). Napio sent all of them into the deep water one after another. The first three had gone down and returned with nothing. The turtle went down and retrieved mud from the bottom and gave it to Napio. He took the mud and rolled it in his hand and created the earth. He let it roll out of his hand and over time has grown to what it is today. After he created the earth, he created women and then men. He had them living separately from one another. The men were shy and afraid, but Napio said to them to not fear and take one as their wife. They had done as he asked, and Napio continued to create the buffalo and bows and arrows for the people so that they could hunt them.[61]

The Blackfoot today

Today, many[quantify] of the Blackfoot live on reserves in Canada. About 8,500 live[when?] on the Montana reservation of 1,500,000 acres (6,100 km2). In 1896, the Blackfoot sold a large portion of their land to the American government, which hoped to find gold or copper deposits. No such mineral deposits were found. In 1910, the land was set aside as Glacier National Park. Some Blackfoot work there and occasional Native American ceremonies are held there.[50]

Unemployment is a challenging problem on the Blackfoot Reservations today. Many people work as farmers, but there are not enough other jobs nearby. To find work, many Blackfoot have relocated from the reservation to towns and cities. Some companies pay the Blackfoot for leasing use of oil, natural gas, and other resources on the land. They operate businesses such as the Blackfoot Writing Company, a pen and pencil factory, which opened in 1972, but it closed in the late 1990s. In Canada, the Northern Piegan make clothing and moccasins, and the Kainai operate a shopping center and factory.[50]

The Blackfoot continue to make advancements in education. In 1974, they opened the Blackfeet Community College in Browning, Montana. The school also serves as tribal headquarters. As of 1979, the Montana state government requires all public school teachers on or near the reservation to have a background in American Indian studies. In 1989, the Siksika tribe in Canada completed a high school to go along with its elementary school.[50]

The Blackfoot Nation in Montana have a blue tribal flag. The flag shows a ceremonial lance or coup stick with 29 feathers. The center of the flag contains a ring of 32 white and black eagle feathers. Within the ring is an outline map of the Blackfoot Reservation. Within the map is depicted a warrior’s headdress and the words “Blackfeet Nation” and “Pikuni” (the name of the tribe in the Algonquian native tongue of the Blackfeet).[50]

Continuing traditions

The Blackfoot continue many cultural traditions of the past and hope to extend their ancestors' traditions to their children. They want to teach their children the Pikuni language as well as other traditional knowledge. In the early 20th century, a white woman named Frances Densmore helped the Blackfoot record their language. During the 1950s and 1960s, few Blackfoot spoke the Pikuni language. In order to save their language, the Blackfoot Council asked elders who still knew the language to teach it. The elders had agreed and succeeded in reviving the language, so today the children can learn Pikuni at school or at home. In 1994, the Blackfoot Council accepted Pikuni as the official language.[50]

The people also revived the Black Lodge Society, responsible for protecting songs and dances of the Blackfoot.[50] They continue to announce the coming of spring by opening five medicine bundles, one at every sound of thunder during the spring.[50] One of the biggest celebrations is called the North American Indian Days. Lasting four days, it is held during the second week of July in Browning. Lastly, the Sun Dance, which was illegal from the 1890s-1934, has been practiced again for years. While it was illegal, the Blackfoot held it in secret. [citation needed] Since 1934, they have practised it every summer. The event lasts eight days - time filled with prayers, dancing, singing, and offerings to honor the Creator. It provides an opportunity for the Blackfoot to get together and share views and ideas with each other, while celebrating their culture's most sacred ceremonies.[50]

Notable Blackfoot people

- Elouise Cobell, who led the lawsuit that forced the US Government to reform individual Indian trusts

- Byron Chief-Moon, performer and choreographer

- Crowfoot, (ISAPO-MUXIKA - "Crow Indian's Big Foot", also known in French as Pied de Corbeau), Chief of the Big Pipes band (later renamed Moccasin band, a splinter band of the Biters band), Head Chief of the South Siksika, by 1870 one of three Head Chiefs of the Siksika or the Blackfoot proper

- Old Sun (Sun Old Man - NATOS-API, until 1860 also known as White Shell Old Man, * 1819 - d. 26 Jan. 1897), a revered medicine man, Chief of the All Medicine Men band (Mo-tah'-tos-iks - “Many Medicines”), Head Chief of the North Siksika,[63] one of the three Head Chiefs of the Siksika

- Aatsista-Mahkan (“Running Rabbit”, * about 1833 - d. January 1911), since 1871 Chief of the Biters band (Ai-sik'-stuk-iks) of the Siksika, signed Treaty No.7 in 1877, along with Crowfoot, Old Sun, Red Crow, and other leaders

- A-ca-oo-mah-ca-ye (Ac ko mok ki, Ak ko mock ki, A’kow-muk-ai - “Feathers”, since he took the name Old Swan), since about 1820 Chief of the Old Feathers’ band, his personal following was known as the Bad Guns band, consisted of about 400 persons, along with Old Sun and Three Suns (No-okskatos) one of three Head Chiefs of the Siksika

- Red Crow (MÉKAISTO, also known as Captured the Gun Inside, Lately Gone, Sitting White Buffalo, and John Mikahestow, * about 1830 - d. 28 Aug. 1900), nephew of PEENAQUIM, Chief of the Fish Eaters band (Mamyowis) of the Kainai, after signing Treaty 7, he centralized the control of several bands and became the leading Head Chief of the Kainai

- PEENAQUIM (Pe-na-koam, Penukwiim - “Seen From Afar”, “far seer”, “far off in sight”, “far off dawn”, also known as Onis tay say nah que im - “Calf Rising in Sight”, and Bull Collar, about *1810 - d. 1869 by smallpox near Lethbridge),[64] son of Two Suns, Chief of the Fish Eaters band (Mamyowis), leading Chief of the Kainai, his tribal following is estimated at the time of his death as being 2,500 people

- Calf Shirt (ONISTAH-SOKAKSIN - “Calf Shirt”, also called Minixi - “Wild Person”, d. in the winter of 1873–74 at Fort Kipp, Alberta), Chief of the Lone Fighters band (Nitayxkax) of the Kainai, was known for his constant hostility to white traders[65][66]

- Stu-mick-o-súcks (“Buffalo Bull's Back Fat”), Head Chief of the Kainai, painted at Fort Union in 1832

- Jerry Potts (1840–1896), (also known as Ky-yo-kosi - “Bear Child”), was a Canadian American plainsman, buffalo hunter, horse trader, interpreter, and scout of Kainai-Scottish descent, considered himself Piegan, became a minor Kainai chief

- Earl Old Person (Cold Wind or Changing Home), Blackfeet tribal chairman from 1964-2008 and honorary lifetime chief of the Blackfoot

- Faye HeavyShield, Kainai sculptor and installation artist

- Rickey Medlocke, lead singer/guitarist of Blackfoot[67]

- Shorty Medlocke, blues musician (Rickey's grandfather)

- Steve Reevis, actor who appeared in Fargo, Dances with Wolves, Last of the Dogmen, Comanche Moon and many other motion pictures and television shows.[68][69]

- James Welch (1940–2003), Blackfeet-Gros Ventre author

- Joe Hipp, Heavyweight boxer, known for his war against Tommy Morrison and for being the first Native American to challenge for the WBA World Heavyweight Title.[70][failed verification]

- Stephen Graham Jones, Author, is a member of the Blackfeet Nation.

See also

Notes

- ^ Compare to Ojibwe: Anishinaabeg and Quinnipiac: Eansketambawg

- ^ "Blackfoot History". Head Smashed In Buffalo Jump. Alberta Culture. May 22, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012. http://history.alberta.ca/headsmashedin/history/blackfoothistory/blackfoothistory.aspx

- ^ Linda Matt Juneau: Small Robe Band of Blackfeet: Ethnogenesis by Social and Religious Transformation

- ^ Informational Sites on the Blackfoot Confederacy and Lewis & Clark

- ^ "The Blackfoot Tribes", Science 6, no. 146 (November 20, 1885), 456-458, JSTOR 1760272.

- ^ Annis May Timpson: First Nations, First Thoughts: The Impact of Indigenous Thought in Canada, University of British Columbia, 2010, ISBN 978-0-7748-1552-9

- ^ Nitawahsin-nanni- Our Land

- ^ a b Gibson, 5.

- ^ Grinnel, George Bird. "Early Blackfoot History." American Anthropologist. Vol. 5, no. 2 (April 1892): 153-164.

- ^ Gibson, The Blackfeet People of the Dark Moccasins, 1

- ^ Taylor, 9.

- ^ Alex Johnston, "Blackfoot Indian Utilization of the Flora of the Northwestern Great Plains," Economic Botany 24, no. 3 (Jul - Sep., 1970), 301-324, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4253161.

- ^ a b David Murdoch, "North American Indian", eds. Marion Dent and others, Vol. Eyewitness Books(Dorling Kindersley Limited, London: Alfred A.Knopf, Inc., 1937), 28-29.

- ^ Gibson, 14

- ^ Taylor, 2

- ^ Helen B. West, "Blackfoot Country," Montana: The Magazine of Western History 10, no. 4 (Autumn, 1960), 34-44, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4516437.

- ^ Gibson, 15

- ^ a b Grinnell, Early Blackfoot History, pp. 153-164

- ^ Stuart J. Baldwin, "Blackfoot Neologisms," International Journal of American Linguistics 60, no. 1 (Jan., 1994), 69-72, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1265481.

- ^ a b Murdoch, North American Indian, p. 28

- ^ Taylor, 4

- ^ Royal B. Hassrick, The Colorful Story of North American Indians, Vol. Octopus Books, Limited (Quarry Bay, Hong Kong: Mandarin Publishers Limited, 1974), 77.

- ^ Bruce Vandervort: Indian Wars of Canada, Mexico, and the United States 1812-1900.Taylor & Francis, 2005, ISBN 978-0-415-22472-7

- ^ Hungrywolf, Adolf (2006). The Blackfoot Papers. Skookumchuck, British Columbia: The Good Medicine Cultural Foundation. p. 233. ISBN 0-920698-80-8. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Names for Peoples/Tribes

- ^ the Cree called them Amiskiwiyiniw or Amisk Wiyiniwak and the Dakelh Tsat'en, Tsattine or Tza Tinne - both mean - 'Beaver People', so they were formerly often referred in English as Beaver

- ^ Joachim Fromhold: The Western Cree (Pakisimotan Wi Iniwak)

- ^ http://segonku.unl.edu/~ahodge/aftermath.html

- ^ a b Ambrose, Stephen. Undaunted Courage. p. 389.

- ^ Gibson, 23

- ^ a b Gibson, 23-29

- ^ "Both versions of Colter's Run".

- ^ "Colter the Mountain Man". Lewis-Clark.org.

- ^ Brown, 2

- ^ Brown, 3

- ^ Brown, 4-5

- ^ Taylor, 43

- ^ Frazier, Ian (1989). Great Plains (1st ed.). Toronto, Canada: Collins Publishers. pp. 50–52.

- ^ Dempsey, H. A. (1972). Crowfoot, chief of the Blackfeet, ([1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, P. 88-89

- ^ Dempsey, H. A. (1972). Crowfoot, chief of the Blackfeet, ([1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, P. 91

- ^ Dempsey, H. A. (1972). Crowfoot, chief of the Blackfeet, ([1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, P. 188-192

- ^ A descendant of Heavy Runner telaccessed February 6, 2011

- ^ http://blackfootdigitallibrary.org/ 2011, CarolMurrayTellsBakerMassacre1.flv

- ^ "The Marias Massacre". Legend of America. Retrieved 21/05/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Murdoch, North American Indian, 34

- ^ Gibson, 26

- ^ Gibson, 27–28

- ^ Murdoch, North American Indian, 28-29

- ^ a b Gibson, 31-42

- ^ a b Murdoch, North American Indian, 29

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gibson, 35-42

- ^ Taylor, 11

- ^ a b Gibson, 17

- ^ Gibson, 19

- ^ Gibson, 19-21

- ^ "Ceremonies". Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park. Retrieved 26/05/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Taylor, 14-15

- ^ Gordon C. Baldwin, Games of the American Indian (Toronto, Canada and the New York, United States of America: George J. McLeod Limited, 1969), 115.

- ^ a b c Taylor, 14

- ^ "Sammi-Headresses". Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park. Retrieved 06/03/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ George Bird Grinnell, "A Blackfoot Sun and Moon Myth," The Journal of American Folklore 6, no. 20 (Jan - Mar., 1893), 44-47, http://www.jstor.org/stable/534278.

- ^ John Maclean, "Blackfoot Mythology," The Journal of American Folklore 6, no. 22 (Jul - Sep., 1893), 165-172, http://www.jstor.org/stable/533004.

- ^ "Source Directory Listings in Kentucky." US Department of the Interior Indian Arts and Crafts Board. (retrieved 22 September 2011)

- ^ Leaders and Chiefs

- ^ PEENAQUIM

- ^ ONISTAH-SOKAKSIN (Calf Shirt)

- ^ after Calf Shirt’s death his band was amalgamated with the Many Fat Horses band (Awaposo-otas) under the leadership of Aka-kitsipimi-otas ("Many Spotted Horses"), a wealthy and respected war chief; the new band kept the name of the largest group, Nitayxkax

- ^ Native American Music Awards/Hall of Fame website

- ^ [1] Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. Retrieved May 28, 2013

- ^ [2] New York Times. Retrieved May 28, 2013

- ^ "Blackfoot Culture and History". Native Languages. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

References

- Brown, Alison K., Relations between the Blackfoot-speaking peoples and fur trade companies (c. 1830-1840) (PDF), retrieved July 27, 2011

- Dempsey, Lloyd James (2007), Blackfoot war art: pictographs of the reservation period, 1880-2000, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 978-0-8061-3804-6

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help) - Gibson, Karen Bush (2000). The Blackfeet: People of the Dark Moccasins. Mankato, Minnesota: Capstone Press. ISBN 978-0-7368-4824-4.

- Grinnell, George Bird (1913), Blackfeet Indian Stories, Kessinger Publishing

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help) - Hungry-Wolf, Adolf (2006), The Blackfoot papers, The Blackfeet Heritage Center & Art Gallery, ISBN 0-920698-80-8

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help) - Kehoe, Alice Beck (2007), Mythology of the Blackfoot Indians, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 9780803260238

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Peat, F. David (2005), Blackfoot Physics, Weiser Books, ISBN 978-1-57863-371-5

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help) - Taylor, Colin (1993). Jayne Booth (ed.). What do we Know about the Plains Indians?. New York: Peter Bedrick Books.

External links

- Blackfoot Nation

- Blackfoot Confederacy

- Blackfoot Language and the Blackfoot Indian Tribe

- Walter McClintock Glass Lantern Slides Photographs of the Blackfoot, their homelands, material culture, and ceremonies from the collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- Blackfoot Digital Library, project of Red Crow Community College and the University of Lethbridge

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Blackfeet Indians". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- James Mooney (1913). "Blackfoot Indians". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Blackfoot". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Horatio Hale (June 1886). "Ethnology of the Blackfoot Tribes". Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 29.