Orange (fruit)

This article needs attention from an expert in botany. The specific problem is: Some information seems imprecise and some sources may be outdated. See the talk page for details. (November 2012) |

| Orange | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orange blossoms and oranges on tree | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | C. × sinensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Citrus × sinensis | |

The orange (specifically, the sweet orange) is the fruit of the citrus species Citrus × sinensis in the family Rutaceae.[2] The fruit of the Citrus sinensis is called sweet orange to distinguish it from that of the Citrus aurantium, the bitter orange. The orange is a hybrid, possibly between pomelo (Citrus maxima) and mandarin (Citrus reticulata), cultivated since ancient times.[3]

Probably originating in Southeast Asia,[4] oranges were already cultivated in China as far back as 2500 BC. Arabo-phone peoples popularized sour citrus and oranges in Europe;[5] Spaniards introduced the sweet orange to the American continent in the mid-1500s.

Orange trees are widely grown in tropical and subtropical climates for their sweet fruit, which can be eaten fresh or processed to obtain juice, and for the fragrant peel.[4] They have been the most cultivated tree fruit in the world since 1987,[6] and sweet oranges account for approximately 70% of the citrus production.[7] In 2010, 68.3 million tonnes of oranges were grown worldwide, particularly in Brazil and in the US states of California[8] and Florida.[9]

Botanical information and terminology

All citrus trees belong to the single genus Citrus and remain almost entirely interfertile. This means that there is only one superspecies that includes grapefruits, lemons, limes, oranges, and various other types and hybrids.[10] As the interfertility of oranges and other citrus has produced numerous hybrids, bud unions, and cultivars, their taxonomy is fairly controversial, confusing or inconsistent.[3][7] The fruit of any citrus tree is considered a hesperidium (a kind of modified berry) because it has numerous seeds, is fleshy and soft, derives from a single ovary and is covered by a rind originated by a rugged thickening of the ovary wall.[11][12]

Different names have been given to the many varieties of the genus. Orange applies primarily to the sweet orange – Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck. The orange tree is an evergreen, flowering tree, with an average height of 9 to 10 metres (30 to 33 ft), although some very old specimens can reach 15 metres (49 ft).[13] Its oval leaves, alternately arranged, are 4 to 10 centimetres (1.6 to 3.9 in) long and have crenulate margins.[14] Although the sweet orange presents different sizes and shapes varying from spherical to oblong, it generally has ten segments (carpels) inside, and contains up to six seeds (or pips)[15] and a porous white tissue – called pith or, more properly, mesocarp or albedo[16]— lines its rind. When unripe, the fruit is green. The grainy irregular rind of the ripe fruit can range from bright orange to yellow-orange, but frequently retains green patches or, under warm climate conditions, remains entirely green. Like all other citrus fruits, the sweet orange is non-climacteric. The Citrus sinensis is subdivided into four classes with distinct characteristics: common oranges, blood or pigmented oranges, navel oranges, and acidless oranges.[17][18][19]

Other citrus species also known as oranges are:

- the bitter orange (Citrus aurantium), also known as Seville orange, sour orange – especially when used as rootstock for a sweet orange tree –, bigarade orange and marmalade orange;

- the bergamot orange (Citrus bergamia Risso). It is grown mainly in Italy for its peel, which is used to flavour Earl Grey tea;

- the trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata), sometimes included in the genus (classified as Citrus trifoliata). It often serves as a rootstock for sweet orange trees, especially as a hybrid with other Citrus cultivars. The trifoliate orange is a thorny shrub or small tree grown mostly as an ornamental plant or to set up hedges. It bears a downy fruit similar to a small citrus, used to make marmalade. It is native to northern China and Korea, and is also known as "Chinese bitter orange" or "hardy orange" because it can withstand subfreezing temperatures;[20] and

- the mandarin orange (Citrus reticulata). It has an enormous number of cultivars, most notably the satsuma (Citrus unshiu), the tangerine (Citrus tangerina) and the clementine (Citrus clementina). In some cultivars, the mandarin is very similar to the sweet orange, making it difficult to distinguish between the two. The mandarin, however, is generally smaller and oblate, easier to peel, and less acid.[21]

Orange trees generally are grafted. The bottom of the tree, including the roots and trunk, is called rootstock, while the fruit-bearing top has two different names: budwood (when referring to the process of grafting) and scion (when mentioning the variety of orange).[22]

Etymology

The origin of the term orange is presumably the Dravidian languages, via the Sanskrit word for "orange tree" (नारङग, nāraṅga),[23] whose form has changed over time, after passing through numerous intermediate languages. The fruit is known as "Chinese apple" in several modern languages. Some examples are Dutch sinaasappel[24] (literally, "China's apple") and appelsien, or Low German Apfelsine. In English, however, Chinese apple usually refers to the pomegranate.[25]

Varieties

Common oranges

Common oranges (also called "white", "round", or "blond" oranges) constitute about two-thirds of all the orange production. The majority of this crop is used mostly for juice extraction.[17][19]

Valencia

The Valencia orange is a late-season fruit, and therefore a popular variety when navel oranges are out of season. This is why an anthropomorphic orange was chosen as the mascot for the 1982 FIFA World Cup, held in Spain. The mascot was named Naranjito ("little orange") and wore the colours of the Spanish national football team kit.

Hart's Tardiff Valencia

Thomas Rivers, an English nurseryman, imported this variety from the Azores Islands and catalogued it in 1865 under the name Excelsior. Around 1870, he provided trees to S. B. Parsons, a Long Island nurseryman, who in turn sold them to E. H. Hart of Federal Point, Florida.[26]

Hamlin

This cultivar was discovered by A. G. Hamlin near Glenwood, Florida, in 1879. The fruit is small, smooth, not highly coloured, seedless, and juicy, with a pale yellow coloured juice, especially in fruits that come from lemon rootstock. The tree is high-yielding and cold-tolerant and it produces good quality fruit, which is harvested from October to December. It thrives in humid subtropical climates. In cooler, more arid areas, the trees produce edible fruit, but too small for commercial use.[13]

Trees from groves in hammocks or areas covered with pine forest are budded on sour orange trees, a method that gives a high solids content. On sand, they are grafted on rough lemon rootstock.[6] The Hamlin orange is one of the most popular juice oranges in Florida and replaces the Parson Brown variety as the principal early-season juice orange. This cultivar is now[needs update] the leading early orange in Florida and, possibly, in the rest of the world.[13]

Other varieties of common oranges

- Belladonna: grown in Italy

- Berna: grown mainly in Spain

- Biondo Comune ("ordinary blond"): widely grown in the Mediterranean basin, especially in North Africa, Egypt, Greece (where it is called "koines"), Italy (where it is also known as "Liscio"), and Spain; it also is called "Beledi" and "Nostrale";[17] in Italy, this variety ripens in December, earlier than the competing Tarocco variety[27]

- Biondo Riccio: grown in Italy

- Cadanera: a seedless orange of excellent flavour grown in Algeria, Morocco, and Spain; it begins to ripen in November and is known by a wide variety of trade names, such as Cadena Fina, Cadena sin Jueso, Precoce de Valence ("early from Valencia"), Precoce des Canaries, and Valence san Pepins ("seedless Valencia");[17] it was first grown in Spain in 1870[28]

- Calabrese or Calabrese Ovale: grown in Italy

- Carvalhal: grown in Portugal

- Castellana: grown in Spain

- Clanor: grown in South Africa

- Dom João: grown in Portugal

- Fukuhara: grown in Japan

- Gardner: grown in Florida, this mid-season orange ripens around the beginning of February, approximately the same time as the Midsweet variety; Gardner is about as hardy as Sunstar and Midsweet[29]

- Homosassa: grown in Florida

- Jaffa orange: grown in the Middle East, also known as "Shamouti"

- Jincheng: the most popular orange in China

- Joppa: grown in South Africa and Texas

- Khettmali: grown in Israel and Lebanon

- Kona: a type of Valencia orange introduced in Hawaii in 1792 by Captain George Vancouver; for many decades in the nineteenth century, these oranges were the leading export from the Kona district on the Big Island of Hawaii; in Kailua-Kona, some of the original stock still bears fruit

- Lue Gim Gong: grown in Florida, is an early scion developed by Lue Gim Gong, a Chinese immigrant known as the "Citrus Genius"; in 1888, Lue cross-pollinated two orange varieties – the Hart's late Valencia and the Mediterranean Sweet – and obtained a fruit both sweet and frost-tolerant; this variety was propagated at the Glen St. Mary Nursery, which in 1911 received the Silver Wilder Medal by the American Pomological Society;[6][30] originally considered a hybrid, the Lue Gim Gong orange was later found to be a nucellar seedling of the Valencia type,[31] which is properly called Lue Gim Gong; since 2006, the Lue Gim Gong variety is grown in Florida, although sold under the general name Valencia

- Macetera: grown in Spain, it is known for its unique flavour

- Malta: grown in Pakistan

- Maltaise Blonde: grown in north Africa

- Maltaise Ovale: grown in South Africa and in California under the names of Garey's or California Mediterranean Sweet

- Marrs: grown in Texas, California and Iran, it is relatively low in acid

- Midsweet: grown in Florida, it is a newer scion similar to the Hamlin and Pineapple varieties, it is hardier than Pineapple and ripens later; the fruit production and quality are similar to those of the Hamlin, but the juice has a deeper colour [29]

- Moro Tarocco: grown in Italy, it is oval, resembles a tangelo, and has a distinctive caramel-coloured endocarp; this colour is the result of a pigment called anthocarpium, not usually found in citruses, but common in red fruits and flowers; the original mutation occurred in Sicily in the seventeenth century

- Mosambi: grown in India and Pakistan, it is so low in acid and insipid that it might be classified as acidless

- Narinja: grown in Andhra, South India

- Parson Brown: grown in Florida, Mexico, and Turkey, it once was a widely-grown Florida juice orange, its popularity has declined since new varieties with more juice, better yield, and higher acid and sugar content have been developed; it originated as a chance seedling in Florida in 1865; its fruits are round, medium large, have a thick, pebbly peel and contain 10 to 30 seeds; it still is grown because it is the earliest maturing fruit in the United States, usually maturing in early September in the Valley district of Texas,[19] and from early October to January in Florida;[29] its peel and juice colour are poor, as is the quality of its juice [19]

- Pera: grown in Brazil, it is very popular in the Brazilian citrus industry and yielded 7.5 million tonnes in 2005

- Pera Coroa: grown in Brazil

- Pera Natal: grown in Brazil

- Pera Rio: grown in Brazil

- Pineapple: grown in North and South America and India

- Premier: grown in South Africa

- Rhode Red: is a mutation of the Valencia orange, but the colour of its flesh is more intense; it has more juice, and less acidity and vitamin C than the Valencia; it was discovered by Paul Rhode in 1955 in a grove near Sebring, Florida

- Roble: it was first shipped from Spain in 1851 by Joseph Roble to his homestead in what now is Roble's Park in Tampa, Florida; it is known for its high sugar content

- Queen: grown in South Africa

- Salustiana: grown in North Africa

- Sathgudi: grown in Tamil Nadu, South India

- Seleta, Selecta: grown in Australia and Brazil, it is high in acid

- Shamouti Masry: grown in Egypt; it is a richer variety of Shamouti

- Sunstar: grown in Florida, this newer cultivar ripens in mid-season (December to March) and it is more resistant to cold and fruit-drop than the competing Pineapple variety; the colour of its juice is darker than that of the competing Hamlin [29]

- Tomango: grown in South Africa

- Verna: grown in Algeria, Mexico, Morocco, and Spain

- Vicieda: grown in Algeria, Morocco, and Spain

- Westin: grown in Brazil

Navel oranges

Navel oranges are characterized by the growth of a second fruit at the apex, which protrudes slightly and resembles a human navel. They are primarily grown for human consumption for various reasons: their thicker skin make them easy to peel, they are less juicy and their bitterness – a result of the high concentrations of limonin and other limonoids – renders them less suitable for juice.[17] Their widespread distribution and long growing season have made navel oranges very popular. In the United States, they are available from November to April, with peak supplies in January, February, and March.[32]

According to a 1917 study by Palemon Dorsett, Archibald Dixon Shamel and Wilson Popenoe of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), a single mutation in a Selecta orange tree planted on the grounds of a monastery near Bahia, Brazil, probably yielded the first navel orange between 1810 and 1820.[33] Nevertheless, a researcher at the University of California, Riverside, has suggested that the parent variety was more likely the Portuguese navel orange (Umbigo), described by Antoine Risso and Pierre Antoine Poiteau in their book Histoire naturelle des orangers ("Natural History of Orange Trees", 1818–1822).[33] The mutation caused the orange to develop a second fruit at its base, opposite the stem, as a conjoined twin in a set of smaller segments embedded within the peel of the primary orange.[34] Navel oranges were introduced in Australia in 1824 and in Florida in 1835. In 1870, twelve cuttings of the original tree were transplanted to Riverside, California, where the fruit became known as "Washington".[35] This cultivar was very successful, and rapidly spread to other countries.[33] Because the mutation left the fruit seedless and, therefore, sterile, the only method to cultivate navel oranges was to graft cuttings onto other varieties of citrus trees. The California Citrus State Historic Park and the Orcutt Ranch Horticulture Center preserve the history of navel oranges in Riverside.

Today, navel oranges continue to be propagated through cutting and grafting. This does not allow for the usual selective breeding methodologies, and so all navel oranges can be considered fruits from that single, nearly two-hundred-year-old tree: they have exactly the same genetic make-up as the original tree and are, therefore, clones. This case is similar to that of the common yellow seedless banana, the Cavendish. On rare occasions, however, further mutations can lead to new varieties.[33]

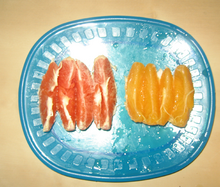

Cara cara navels

Cara cara oranges (also called "red navel") are a type of navel orange grown mainly in Venezuela, South Africa and in California's San Joaquin Valley. They are sweet and comparatively low in acid,[36] with a bright orange rind similar to that of other navels, but their flesh is distinctively pinkish red. It is believed that they have originated as a cross between the Washington navel and the Brazilian Bahia navel,[37] and they were discovered at the Hacienda Cara Cara in Valencia, Venezuela, in 1976.[38]

South African cara caras are ready for market in early August, while Venezuelan fruits arrive in October and Californian fruits in late November.[36][37]

Other varieties of navels

- Bahianinha or Bahia

- Dream Navel

- Late Navel

- Washington or California Navel

Blood oranges

Blood oranges are a natural mutation of C. sinensis, although today the majority of them are hybrids. High concentrations of anthocyanin give the rind, flesh, and juice of the fruit their characteristic dark red colour. Blood oranges were first discovered and cultivated in Sicily in the fifteenth century. Since then they have spread worldwide, but are grown especially in Spain and Italy—under the names of sanguina and sanguinella, respectively.

The blood orange, with its distinct colour and flavour, is generally considered the most delicious juice orange,[17] and has found a niche as an ingredient variation in traditional Seville marmalade.

Other varieties of blood oranges

- Maltese: a small and highly coloured variety, generally thought to have originated in Italy as a mutation and cultivated there for centuries. It also is grown extensively in southern Spain and Malta. It is used in sorbets and other desserts due to its rich burgundy colour.

- Moro: originally from Sicily, it is common throughout Italy. This medium-sized fruit has a relatively long harvest, which lasts from December to April.

- Sanguinelli: a mutant of the Doble Fina, discovered in 1929 in Almenara, in the Castellón province of Spain. It is cultivated in Sicily.

- Scarlet navel: a variety with the same mutation as the navel orange.

- Tarocco: a relatively new variety developed in Italy. It begins to ripen in late January.[27]

Acidless oranges

Acidless oranges are an early-season fruit with very low levels of acid, which are rather insipid. They also are called "sweet" oranges in the U.S., with similar names in other countries: douce in France, sucrena in Spain, dolce or maltese in Italy, meski in North Africa and the Near East (where they are especially popular), şeker portakal ("sugar orange") in Turkey,[39] succari in Egypt, and lima in Brazil.[17]

The lack of acid, which protects orange juice against spoilage in other groups, renders them generally unfit for processing as juice, so they are primarily eaten. They remain profitable in areas of local consumption, but rapid spoilage renders them unsuitable for export to major population centres of Europe, Asia, or the United States.[17]

Attributes

Nutritional value

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 197 kJ (47 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

11.75 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 9.35 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fibre | 2.4 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.12 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.94 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 86.75 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[40] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[41] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This section needs expansion with: nutritional properties (see talk page). You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (November 2012) |

Oranges, like most citrus fruits, are a good source of vitamin C.

Acidity

Being a citrus fruit, the orange is acidic: its pH levels are as low as 2.9,[42] and as high as 4.0.[42][43]

Grading

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has established the following grades for Florida oranges, which primarily apply to oranges sold as fresh fruit: US Fancy, US No. 1 Bright, US No. 1, US No. 1 Golden, US No. 1 Bronze, US No. 1 Russet, US No. 2 Bright, US No. 2, US No. 2 Russet, and US No. 3.[44] The general characteristics graded are colour (both hue and uniformity), firmness, maturity, varietal characteristics, texture, and shape. Fancy, the highest grade, requires the highest grade of colour and an absence of blemishes, while the terms Bright, Golden, Bronze, and Russet concern solely discolouration.

Grade numbers are determined by the amount of unsightly blemishes on the skin and firmness of the fruit that do not affect consumer safety. The USDA separates blemishes into three categories:

- General blemishes: ammoniation, buckskin, caked melanose, creasing, decay, scab, split navels, sprayburn, undeveloped segments, unhealed segments, and wormy fruit

- Injuries to fruit: bruises, green spots, oil spots, rough, wide, or protruding navels, scale, scars, skin breakdown, and thorn scratches

- Damage caused by dirt or other foreign material, disease, dryness, or mushy condition, hail, insects, riciness or woodiness, and sunburn.[44]

The USDA uses a separate grading system for oranges used for juice because appearance and texture are irrelevant in this case. There are only two grades: US Grade AA Juice and US Grade A Juice, which are given to the oranges before processing. Juice grades are determined by three factors:

- The juiciness of the orange

- The amount of solids in the juice (at least 10% solids are required for the AA grade)

- The proportion of anhydric citric acid in fruit solids

History

There are no reports of sweet oranges occurring in the wild. In general, it is believed that sweet orange trees have originated in Southeast Asia, northeastern India, or southern China,[6] and that they were first cultivated in China around 2500 BC.[citation needed]

In Europe, citrus fruits—among them the bitter orange, introduced to Italy by the crusaders in the 11th century—were grown widely in the south for medicinal purposes,[6] but the sweet orange was unknown until the late 15th century or the beginnings of the 16th century, when Italian and Portuguese merchants brought orange trees into the Mediterranean area.[6] Shortly afterward, the sweet orange quickly was adopted as an edible fruit. It also was considered a luxury item and wealthy people grew oranges in private conservatories, called orangeries. By 1646, the sweet orange was well known throughout Europe.[6]

Spanish explorers introduced the sweet orange into the American continent. On his second voyage in 1493, Christopher Columbus took seeds of oranges, lemons, and citrons to Haiti and the Caribbean. Subsequent expeditions in the mid-1500s brought sweet oranges to South America and Mexico, and to Florida in 1565, when Pedro Menéndez de Avilés founded St Augustine.[45] Spanish missionaries brought orange trees to Arizona between 1707 and 1710, while the Franciscans did the same in San Diego, California, in 1769. An orchard was planted at the San Gabriel Mission around 1804 and a commercial orchard was established in 1841 near present-day Los Angeles. In Louisiana, oranges probably were introduced by French explorers.

Archibald Menzies, the botanist and naturalist on the Vancouver Expedition, collected orange seeds in South Africa, raised the seedlings onboard and gave them to several Hawaiian chiefs in 1792. Eventually, the sweet orange was grown in wide areas of the Hawaiian Islands, but its cultivation stopped after the arrival of the Mediterranean fruit fly in the early 1900s.[6][46]

As oranges are rich in vitamin C and do not spoil easily, during the Age of Discovery, Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch sailors planted citrus trees along trade routes to prevent scurvy.

Around 1872, Florida farmers obtained seeds from New Orleans, so many orange groves were established by grafting the sweet orange on to sour orange rootstocks.

Cultivation

Climate

Like most citrus plants, oranges do well under moderate temperatures—between 15.5 and 29 °C (59.9 and 84.2 °F)—and require considerable amounts of sunshine and water. It has been suggested that the use of water resources by the citrus industry in the Middle East is a contributing factor to the desiccation of the region. [citation needed] Another significant element in the full development of the fruit is the temperature variation between summer and winter and, between day and night. In cooler climates, oranges can be grown indoors.

As oranges are sensitive to frost, there are different methods to prevent frost damage to crops and trees when subfreezing temperatures are expected. A common process is to spray the trees with water so as to cover them with a thin layer of ice that will stay just at the freezing point, insulating them even if air temperatures drop far lower. This is because water continues to lose heat as long as the environment is colder than it is, and so the water turning to ice in the environment cannot damage the trees. This practice, however, offers protection only for a very short time.[47] Another procedure is burning fuel oil in smudge pots put between the trees. These devices burn with a great deal of particulate emission, so condensation of water vapour on the particulate soot prevents condensation on plants and raises the air temperature very slightly. Smudge pots were developed for the first time after a disastrous freeze in Southern California in January 1913 destroyed a whole crop.[48]

Propagation

It is possible to grow orange trees directly from seeds, but they may be infertile or produce fruit that may be different from its parent. For the seed of a commercial orange to grow, it must be kept moist at all times. One approach is placing the seeds between two sheets of damp paper towel until they germinate and then planting them, although many cultivators just set the seeds straight into the soil.

Commercially grown orange trees are propagated asexually by grafting a mature cultivar onto a suitable seedling rootstock to ensure the same yield, identical fruit characteristics, and resistance to diseases throughout the years. Propagation involves two stages: first, a rootstock is grown from seed. Then, when it is approximately one year old, the leafy top is cut off and a bud taken from a specific scion variety, is grafted into its bark. The scion is what determines the variety of orange, while the rootstock makes the tree resistant to pests and diseases and adaptable to specific soil and climatic conditions. Thus, rootstocks influence the rate of growth and have an effect on fruit yield and quality.[49]

Rootstocks must be compatible with the variety inserted into them because otherwise, the tree may decline, be less productive, and even die.[49]

Among the several advantages to grafting are that trees mature uniformly and begin to bear fruit earlier than those reproduced by seeds (3 to 4 years in contrast with 6 to 7 years),[50] and that it makes it possible to combine the best attributes of a scion with those of a rootstock.[51]

Principal rootstocks

Today, five types of rootstock predominate in relatively cool climates where cold or freezing weather is probable, especially Florida and southern Europe.

- Sour rootstock: it is the only rootstock that truly is an orange (the Citrus × aurantium or bitter orange). It is vigorous and highly drought-resistant.

- Poncirus trifoliata: it is a close relative of the Citrus genus, sometimes classified as Citrus trifoliata. It is especially resistant to cold, the tristeza virus, and the fungus Phytophthora parasitica (root rot) and grows well in loam soil. Among its disadvantages are its slow growth—it is the slowest growing rootstock—and its poor resistance to heat and drought. It is primarily used in China, Japan, and areas of California with heavy soils.[52]

- Swingle citrumelo: it is tolerant of tristeza virus and Phytophthora parasitica and moderately resistant to salt and freezing.[50] This rootstock selection was hybridized from the Duncan grapefruit (Citrus paradisi Macfadyen) and the Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. by Walter Tennyson Swingle in Eustis, Florida, in 1907. It was released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to nurserymen in 1974.

- Troyer citrange and Carrizo citrange: these reasonably vigorous rootstocks are resistant to Phytophthora parasitica, nematodes, and tristeza virus and show good cold tolerance. They also are highly polyembryonic, so growers can obtain multiple plants from a single seed. Citrange, however, does not do well in clay, calcareous or high-pH soils, and is sensitive to salinity. It is not feasible as rootstock for mandarin scions, as it overgrows them by producing branches of its own in competition with the grafted budwood.[53] Citranges are hybrids of the Washington navel orange and the Poncirus trifoliata. The original crosses, made in the early 1900s by the U.S. Department of Agriculture with the intention of producing cold tolerant scion varieties, were later identified as suitable for use as rootstocks. The commercial use of these rootstocks began in Australia in the 1960s. The Troyer variety generally is found in California, while the Carrizo variety is used in Florida.

- Cleopatra mandarin: it is tolerant of salinity and soil alkalinity and also suitable for shallow soils. It is used primarily in Spain, Australia, and Florida. Dade County, for example, has 85% calcareous soil, a typical trait of land that has been under water.[54] The Cleopatra mandarin, originated in India and introduced into Florida from Jamaica in the mid-nineteenth century, has been distributed and tested as a rootstock throughout the world. Nowadays, however, it is considered an inferior rootstock because it is sensitive to many diseases, grows slowly, and is difficult to propagate.[55]

Other rootstock varieties in the United States

- African shaddock X trifoliate hybrid[33]

- Benton citrange trifoliate hybrid[33]

- Borneo Rangpur lime[33]

- Bitters C-22 citrange (X Citroncirus sp. Rutaceae): it was hybridized at the USDA U.S. Date and Citrus Station in Indio, California, and developed further by the University of California, Riverside. It is used primarily as rootstock for navel oranges in California. In 2009, a report suggested it also may be useful to replace sour orange rootstock for grapefruit in Texas because it is tolerant of calcareous soil.[56][57] Its name is not related to the bitter orange: it was named after Dr William Bitters, professor of Horticulture and a curator of the Citrus Variety Collection.

- Carpenter C-54 citrange[57]

- C-32 citrange trifoliate hybrid[33]

- C-35 citrange trifoliate hybrid[33]

- Calamondin kumquat hybrid[33]

- Carrizo citrange trifoliate hybrid[33]

- Citradia trifoliate hybrid[33]

- Citremon trifoliate hybrid (CRC 1449)[33]

- Citrumelo trifoliate hybrid C190[33]

- Citrumelo trifoliate hybrid (CRC 1452)[33]

- Citrumelo trifoliate hybrid (CRC 4475)[33]

- Citrus macrophylla (Alemow)[33]

- Citrus volkameriana (Volkamer lemon)[33]

- Cleopatra mandarin X trifoliate hybrid X639[33]

- Flying dragon trifoliate (CRC 3330A)[33]

- Fraser Seville sour orange[33]

- Furr C-57 citrange[57]

- Goutoucheng sour orange (CRC 3929)[33]

- Goutoucheng sour orange (CRC 4004)[33]

- Grapefruit seedling (CRC 343)[33]

- Pomeroy trifoliate[33]

- Rangpur lime X Troyer citrange hybrid[33]

- Rich 16-6 trifoliate[33]

- Rubidoux trifoliate[33]

- Rusk citrange trifoliate orange[33]

- Satsuma X trifoliate hybrid[33]

- Schaub rough lemon[33]

- Small-leaf trifoliate[33]

- Smooth Flat Seville sour orange[33]

- Sun Chu Sha Kat mandarin[33]

- US 119 (Grapefruit X trifoliate) X Sweet Orange hybrid[33]

- Vangassay rough lemon[33]

- Yuma Ponderosa lemon pummelo hybrid[33]

- Zhuluan sour orange hybrid (CRC 3930)[33]

- Zhuluan sour orange hybrid (CRC 3981)[33]

Harvest

Canopy-shaking mechanical harvesters are being used increasingly in Florida to harvest oranges. Current canopy shaker machines use a series of six-to-seven-foot long tines to shake the tree canopy at a relatively constant stroke and frequency.[58]

Degreening

Oranges must be mature when harvested.[citation needed] In the United States, laws forbid harvesting immature fruit for human consumption in Texas, Arizona, California and Florida.[59] Ripe oranges, however, often have some green or yellow-green colour in the skin. Ethylene gas is used to turn green skin to orange. This process is known as "degreening", also called "gassing", "sweating", or "curing".[59] Oranges are non-climacteric fruits and cannot post-harvest ripen internally in response to ethylene gas, though they will de-green externally.[60]

Storage

Commercially, oranges can be stored by refrigeration in controlled-atmosphere chambers for up to 12 weeks after harvest. Storage life ultimately depends on cultivar, maturity, pre-harvest conditions, and handling.[61] In stores and markets, however, oranges should be displayed on non-refrigerated shelves.

At home, oranges have a shelf life of about one month.[62] In either case, optimally, they are stored loosely in an open or perforated plastic bag.[62]

Pests and diseases

Cottony cushion scale

The first major pest that attacked orange trees in the United States was the cottony cushion scale (Icerya purchasi), imported from Australia to California in 1868. Within 20 years, it wiped out the citrus orchards around Los Angeles, and limited orange growth throughout California. In 1888, the USDA sent Alfred Koebele to Australia to study this scale insect in its native habitat. He brought back with him specimens of Novius cardinalis, an Australian ladybird beetle, and within a decade the pest was controlled.[26]

Citrus greening disease

The citrus greening disease, caused by the bacterium Liberobacter asiaticum, has been the most serious threat to orange production since 2010. It is characterized by streaks of different shades on the leaves, and deformed, poorly-coloured, unsavoury fruit. In areas where the disease is endemic, citrus trees live for only five to eight years and never bear fruit suitable for consumption.[63] In the western hemisphere, it was discovered in Florida in 1998, where it has attacked nearly all the trees ever since. It was also reported in Brazil by Fundecitrus Brasil in 2004.[63] As from 2009, 0.87% of the trees in Brazil's main orange growing areas (São Paulo and Minas Gerais) showed symptoms of greening, which means an increase of 49% over 2008.[64]

The disease is spread primarily by two species of psyllid insects. One of them is the Asian citrus psyllid (Diaphorina citri Kuwayama), an efficient vector of the Liberobacter asiaticum. Generalist predators such as the ladybird beetles Curinus coeruleus, Olla v-nigrum, Harmonia axyridis, and Cycloneda sanguinea, and the lacewings Ceraeochrysa spp. and Chrysoperla spp. make significant contribution to the mortality of the Asian citrus psyllid, which results in 80–100% reduction in psyllid populations. In contrast, parasitism by Tamarixia radiata, a species-specific parasitoid of the Asian citrus psyllid, is variable and generally low in southwest Florida: in 2006, it amounted to a reduction of less than 12% from May to September and 50% in November.

In 2007, foliar applications of insecticides reduced psyllid populations for a short time, but also suppressed the populations of predatory ladybird beetles. Soil application of aldicarb provided limited control of Asian citrus psyllid, while drenches of imidacloprid to young trees were effective for two months or more.[65]

Management of citrus greening disease is difficult and requires an integrated approach that includes use of clean stock, elimination of inoculum via voluntary and regulatory means, use of pesticides to control psyllid vectors in the citrus crop, and biological control of psyllid vectors in non-crop reservoirs. Citrus greening disease is not under completely successful management.[63]

Greasy spot

Greasy spot, a fungal disease caused by the Mycosphaerella citri, produces leaf spots and premature defoliation, thus reducing the tree's vigour and yield. Ascospores of M. citri are generated in pseudothecia in decomposing fallen leaves.[66] Once mature, ascospores are ejected and subsequently dispersed by air currents.

Production

Brazil is the world's leading orange producer, with an output almost as high as that of the next three countries combined (the United States, India, and China). Orange groves are located mainly in the state of São Paulo, in the southeastern region of Brazil, and account for approximately 80% of the national production. As almost 99% of the fruit is processed for export, 53% of total global frozen concentrated orange juice production comes from this area and the western part of the state of Minas Gerais. In Brazil, the four predominant orange varieties used for obtaining juice are Hamlin, Pera Rio, Natal, and Valencia.[67][68]

The United States is the second largest producer. Groves are located especially in Florida, California, Texas, and Arizona. The majority of California's crop is sold as fresh fruit, whereas Florida's oranges are destined to juice products. Mid-south Florida produces about half as many oranges as Brazil, but the bulk of its orange juice is not exported. The Indian River area of Florida is known for the high quality of its juice, which often is sold fresh in the U.S. and frequently blended with juice produced in other regions because Indian River trees yield very sweet oranges, but in relatively small quantities.[69]

Production of orange juice between the São Paulo and mid-south Florida areas makes up roughly 85% of the world market. Brazil exports 99% of its production, while 90% of Florida's production is consumed in the U.S.[70]

Orange juice is traded internationally in the form of frozen, concentrated orange juice to reduce the volume used so that storage and transportation costs are lower.[71]

The European Union is the third largest producer of oranges worldwide.[68]

| Top orange producers (million tonnes) |

2005 | 2008 | 2010 | |

| 17.9 | 18.5 | 18.1 | ||

| 8.4 | 9.1 | 7.5 | ||

| 3.3 | 4.9 | 6.0 | ||

| 2.7 | 4.2 | 5.0* | ||

| 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.1 | ||

| 2.4 | 3.4 | 3.1 | ||

| 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.4 | ||

| 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.4 | ||

| 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.0 | ||

| 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.7 | ||

| 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.5 | ||

| 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.5 | ||

| World Total | 63.1 | 69.6 | 68.3 | |

| *= unofficial figure. All figures for 2005 and 2008 are official. Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Economic and Social Department: the Statistical Division[72] | ||||

Other countries with a significant production of oranges are South Africa, Morocco, and Argentina.

Juice and other products

Oranges, whose flavour may vary from sweet to sour, are commonly peeled and eaten fresh or squeezed for juice. The thick bitter rind is usually discarded, but can be processed into animal feed by desiccation, using pressure and heat. It also is used in certain recipes as a food flavouring or garnish. The outermost layer of the rind can be thinly grated with a zester to produce orange zest. Zest is popular in cooking because it contains the oil glands and has a strong flavour similar to that of the orange pulp. The white part of the rind, including the pith, is a source of pectin and has nearly the same amount of vitamin C as the flesh and other nutrients.

Although not so juicy or tasty as the flesh, orange peel is edible and has higher contents of vitamin C and more fibre. It also contains citral, an aldehyde that antagonizes the action of vitamin A, Particularly in environments where resources are scarce and therefore maximum nutritional value must be obtained with the minimum generation of waste, for example, on a submarine, orange peels have been consumed routinely. Since large concentrations of pesticides have been found in orange peels,[73] some organizations[which?] recommend consumption of the peel of only organically grown and processed oranges, where chemical pesticides or herbicides would not have been used.[74]

Products made from oranges

- Orange juice is obtained by squeezing the fruit on a special tool (a juicer or squeezer) and collecting the juice in a tray underneath. This can be made at home or, on a much larger scale, industrially. Brazil is the largest producer of orange juice in the world, followed by the U.S., where it is one of the commodities traded on the New York Board of Trade.

- Frozen orange juice concentrate is made from freshly squeezed and filtered orange juice.[75]

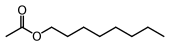

- Sweet orange oil is a by-product of the juice industry produced by pressing the peel. It is used for flavouring food and drinks and also in the perfume industry and aromatherapy for its fragrance. Sweet orange oil consists of approximately 90% D-limonene, a solvent used in various household chemicals, such as wood conditioners for furniture and—along with other citrus oils—detergents and hand cleansers. It is an efficient cleaning agent with a pleasant smell, promoted for being environmentally friendly and therefore, preferable to petrochemicals. D-limonene is, however, classified from slightly toxic to humans,[76] to very toxic to marine life in different countries.[77]

Although once thought to cause renal cancer in rats, limonene is now considered a natural chemopreventive agent in humans,[78][79] since there is no evidence for its carcinogenicity or genotoxicity. The Carcinogenic Potency Project estimates that D-limonene causes human cancer on a level roughly equivalent to that caused by exposure to caffeic acid via dietary coffee intake,[80] whereas the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies it under Class 3, which means it is not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans.[81]

Orange blossoms are used in several different ways, as are fruit peels and the leaves and wood of the tree.

- The orange blossom, which is the state flower of Florida,[82] is highly fragrant and traditionally associated with good fortune. It has long been popular in bridal bouquets and head wreaths.

- Orange blossom essence is an important component in the making of perfume.

- Orange blossom petals can also be made into a delicately citrus-scented version of rosewater, known as "orange blossom water" or "orange flower water". It is a common ingredient in French and Middle Eastern cuisines, especially in desserts and baked goods. In some Middle Eastern countries, drops of orange flower water are added to disguise the unpleasant taste of hard water drawn from wells or stored in qullahs (traditional Egyptian water pitchers made of porous clay). In the United States, orange flower water is used to make orange blossom scones and marshmallows.

- In Spain, fallen blossoms are dried and used to make tea.

- Orange blossom honey (or citrus honey) is obtained by putting beehives in the citrus groves while trees bloom. By this method, bees also pollinate seeded citrus varieties. This type of honey has an orangey taste and is highly prized.

- Marmalade usually is made with Seville oranges. All parts of the fruit are used: the pith and pips (separated and placed in a muslin bag) are boiled in a mixture of juice, slivered peel, sliced-up flesh, sugar, and water to extract their pectin, which helps the conserve to set.

- Orange peel is used by gardeners as a slug repellent.

- Orange leaves can be boiled to make tea.

- Orangewood sticks are used as cuticle pushers in manicures and pedicures, and as spudgers for manipulating slender electronic wires.

- Orangewood is used in the same way as mesquite, oak, and hickory for seasoning grilled meat.

|

|

|

Etymology

The word orange derives from the Sanskrit word for "orange tree" (नारङ्ग nāraṅga), probably of Dravidian origin.[23] The Sanskrit word reached European languages through Persian نارنگ (nārang) and its Arabic derivative نارنج (nāranj).

The word entered Late Middle English in the fourteenth century via Old French orenge (in the phrase pomme d'orenge).[83] The French word, in turn, comes from Old Provençal auranja, based on Arabic nāranj.[23] In several languages, the initial n present in earlier forms of the word dropped off because it may have been mistaken as part of an indefinite article ending in an n sound—in French, for example, une norenge may have been heard as une orenge. This linguistic change is called juncture loss. The colour was named after the fruit,[84] and the first documented use in this sense dates to 1542.[citation needed]

As Portuguese merchants were presumably the first to introduce the sweet orange in Europe, in several modern Indo-European languages the fruit has been named after them. Some examples are Albanian portokall, Bulgarian портокал (portokal), Greek πορτοκάλι (portokali), Persian پرتقال (porteghal), and Romanian portocală.[85][86] Related names can be found in other languages, such as Arabic البرتقال (bourtouqal), Georgian ფორთოხალი (p'ort'oxali), and Turkish portakal.[85] In Italy, words derived from Portugal (Portogallo) to refer to the sweet orange are in common use in most dialects throughout the country, in contrast to standard Italian arancia.[87]

In other Indo-European languages, the words for orange allude to the eastern origin of the fruit and can be translated literally as "apple from China". Some examples are Low German Apfelsine, Dutch appelsien and sinaasappel, Swedish apelsin, and Norwegian appelsin.[86] A similar case is Puerto Rican Spanish china.[88][89]

Various Slavic languages use the variants pomaranč (Slovak), pomeranč (Czech), pomaranča (Slovene), and pomarańcza (Polish), all from Old French pomme d'orenge.[90][failed verification]

See also

- Cam sành (Green orange or Longan. Citrus reticulata × maxima)

- Orange production in Brazil

- University of California Citrus Experiment Station

- Eliza Tibbets (for the history of orange groves in California, US)

References

- ^ "Citrus sinensis information from NPGS/GRIN". www.ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ "Citrus ×sinensis (L.) Osbeck (pro sp.) (maxima × reticulata) sweet orange". Plants.USDA.gov.

- ^ a b Nicolosi, E.; Deng, Z. N.; Gentile, A.; La Malfa, S.; Continella, G.; Tribulato, E. (2000). "Citrus phylogeny and genetic origin of important species as investigated by molecular markers". TAG Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 100 (8): 1155–1166. doi:10.1007/s001220051419.

- ^ a b Citrus sinensis information from NPGS/GRIN. Ars-grin.gov. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ http://websites.lib.ucr.edu/agnic/webber/Vol1/Chapter1.htm

- ^ a b c d e f g h Morton, J., Fruits of Warm Climates (1987) Miami, FL, pp. 134–142. Cite error: The named reference "morton" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Organisms. Citrus Genome Database

- ^ "Top production oranges 2010". FAO Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ "States Which Produce the Most of Popular Kids Food". Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Superspecies. Scientific-web.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ Bailey, H. and E. Bailey. 1976. Hortus Third. Cornell University MacMillan. N.Y. p 275.

- ^ Seed and Fruits. Esu.edu. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ a b c Webber, Herbert John; rev Walter Reuther and Harry W. Lawton (1967–1989) [1943]. "4". The Citrus Industry, Horticultural Varieties of Citrus. Riverside CA: University of California Division of Agricultural Sciences.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Citrus sinensis – Encyclopedia of Life. EOL. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ pip – Definition with thesaurus, examples, audio and more. Yourdictionary.com (2011-09-23). Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ pith – Definition with thesaurus, examples, audio and more. Yourdictionary.com (2011-09-23). Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kimball, Dan A. (June 30, 1999). "Citrus processing: a complete guide" (Document). New York: Springer. p. 450Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|url=and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|edition=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Webber, Herbert John; rev Walter Reuther and Harry W. Lawton (1967–1989) [1903]. "The Citrus Industry" (Document). Riverside CA: University of California Division of Agricultural SciencesTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|edition=and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c d Home Fruit Production – Oranges, Julian W. Sauls, Ph.D., Professor & Extension Horticulturist, Texas Cooperative Extension (December, 1998), aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu

- ^ "Plant of the Week. Hardy Orange or Trifoliate Orange. Latin: Poncirus trifoliat". University of Arkansas. Division of Agriculture.

- ^ Tangerines (mandarin oranges) nutrition facts and health benefits. Nutrition-and-you.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ Scion – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ a b c "Definition of orange". Collins English Dictionary (collinsdictionary.com).

- ^ sinaasappel – English translation – bab.la Dutch-English dictionary. En.bab.la (2011-03-24). Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ a b John Eliot Coit (1915). Citrus fruits: an account of the citrus fruit industry, with special reference to California requirements and practices and similar conditions. The Macmillan Company. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ a b Material Identification Sheet. Webcapua.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-02 (in French).

- ^ Citrus Pages / Sweet oranges. Users.kymp.net. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ a b c d James J. Ferguson Your Florida Dooryard Citrus Guide – Appendices, Definitions and Glossary. edis.ifas.ufl.edu

- ^ "The Life of Lue Gim Gong". West Volusia Historical Society. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Orange. Hort.purdue.edu. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ Types of Oranges – Blood, Navel, Valencia. Sunkist. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Staff of the Citrus Experiment Station, College of Natural and Agricultural Sciences (1910–2011). "Sweet Oranges and Their Hybrids". Citrus Variety Collection. University of California (Riverside). Retrieved January 19, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) Cite error: The named reference "riverside" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Commodity Fact Sheet: Citrus Fruits" (PDF). California Foundation for Agriculture in the Classroom. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- ^ William Saunders, "Experimental Gardens and Grounds", in USDA, Yearbook of Agriculture 1897, 180 ff; USDA, Yearbook of Agriculture 1900, 64.

- ^ a b "UBC Botanical Garden, Botany Photo of the Day".

- ^ a b Allen Susser (1 May 1997). The Great Citrus Book: A Guide with Recipes. Ten Speed Press. ISBN 978-0-89815-855-7. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Cara Cara navel orange. UC Riverside

- ^ Portakal Çeşitleri: Seker portakal (in Turkish)

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). "Chapter 4: Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". In Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). pp. 120–121. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ a b Walton B. Sinclair, E.T. Bartholomew, R. C. Raamsey (1945). "ANALYSIS OF THE ORGANIC ACIDS OF ORANGE JUICE" (PDF). Plant Physiol. 20 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1104/pp.20.1.3. PMC 437693. PMID 16653966.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (July 16, 1999). "Outbreak of Salmonella Serotype Muenchen Infections Associated with Unpasteurized Orange Juice – United States and Canada, June 1999". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 48 (27). Centers for Disease Control: 582–585. PMID 10428096.

- ^ a b United States Standards for Grades of Florida Oranges and Tangelos (USDA; February, 1997)

- ^ Sauls, Julian W. (December 1998). "HOME FRUIT PRODUCTION-ORANGES". The Texas A&M University System. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Ronald Mau and Jayma Martin Kessing (April 2007). "Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann)". Knowledge Master, University of Hawaii. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "How Cold Can Water Get?". NEWTON BBS. Argonne National Laboratory. 2002-09-08. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ Moore, Frank Ensor (1995). "Redlands Astride the Freeway: The Development of Good Automobile Roads". Redlands, California: Moore Historical Foundation: 9. ISBN 0-914167-07-3.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Lacey, Kevin (July 2012). "Citrus rootstocks for WA" (PDF). Government of WA. Department of Agriculture and Food. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ a b Dr Price, Martin. "Citrus Propagation and Rootstocks". ultimatecitrus.com. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Citrus Propagation. Research Program on Citrus Rootstock Breeding and Genetics. ars-grin.gov

- ^ "Poncirus trifoliata" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-21.

- ^ "Troyer & Carrizo citrange" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-21.

- ^ SL 183/TR004: Calcareous Soils In Miami-Dade County. Edis.ifas.ufl.edu (2009-07-10). Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ "Cleopatra mandarin" (PDF). Archived from lia.com.au/PDFs/resources/varieties/Cleopatra_mandarin.pdf the original (PDF) on 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ bittersC22. Citrusvariety.ucr.edu. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ a b c "Summary of Rootstock Trials (Roose program" (PDF). Plantbiology.ucr.edu. 5/12/09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ R. Ehsani et al. "In-situ Measurement of the Actual Detachment Force of Oranges Harvested by a Canopy Shaker Harvesting Machine". Abstracts for the 2007 Joint Annual Meeting of the Florida State Horticulture Society. (June, 2007)

- ^ a b Alfred B. Wagner and Julian W. Sauls. "Harvesting and Pre-pack Handling". The Texas A&M University System. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Mary Lu Arpaia and Adel A. Kader. "Orange: Recommendations for Maintaining Postharvest Quality". UCDavis Postharvest Technology Center.

- ^ M.A. Ritenour, Orange. From The Commercial Storage of Fruits, Vegetables, and Florist and Nursery Stocks. USDA (2004)

- ^ a b Home Storage Guide for Fresh Fruits & Vegetables. Canadian Produce Marketing Association. Retrieved March 2012.

- ^ a b c Asian Citrus Psllids (Sternorryncha: Psyllidae) and Greening Disease of Citrus, by Susan E. Halbert and Keremane L. Manjunath, Florida Entomologist (Abstract. September 2004) p. 330 FCLA.edu

- ^ GAIN Report Number: BR9006, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (June, 2009)

- ^ Jawwad A. Qureshi and Philip A. Stansly (June, 2007) "Integrated approaches for managing the Asian citrus psyllid (Homoptera: Psyllidae) in Florida". Abstracts for the 2007 Joint Annual Meeting of the Florida State Horticulture Society

- ^ S.N. Mondal, et al. (June, 2007) "Effect of Water Management and Soil Application of Nitrogen Fertilizers, Petroleum Oils, and Lime on Inoculum Production by Mycosphaerella citri, the Cause of Citrus Greasy Spot". Abstracts for the 2007 Joint Annual Meeting of the Florida State Horticulture Society

- ^ GAIN Report Number: BR10005, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (6/15/2010)

- ^ a b Frozen Concentrated Orange Juice (FCOJ) Commodity Market, Credit and Finance Risk Analysis. credfinrisk.com Cite error: The named reference "credit" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "History of the Indian River Citrus District". Indian River Citrus League (ircitrusleague.org). Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. "USDA – U.S and the World Situation: Citrus" (PDF).

- ^ Thomas H. Spreen. Projections of World Production and Consumption of Citrus to 2010.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". FAO Statistics. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ^ Oranges are not the safest fruit - they all exceed pesticide limits. The Independent, 18 December 2005.

- ^ "Is It Healthy to Eat Orange Peels?". Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Chet Townsend. "The Story of Florida Orange Juice: From the Grove to Your Glass".[self-published source?]

- ^ Kegley SE, Hill BR, Orme S, Choi AH. "Limonene". PAN Pesticide Database. Pesticide Action Network.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "D-LIMONENE". International Programme on Chemical Safety. 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Crowell PL (1999). "Prevention and therapy of cancer by dietary monoterpenes". The Journal of Nutrition. 129 (3): 775S – 778S. PMID 10082788.

- ^ Tsuda H; Ohshima Y; Nomoto H; et al. (2004). "Cancer prevention by natural compounds". Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 19 (4): 245–63. doi:10.2133/dmpk.19.245. PMID 15499193.

- ^ "Ranking Possible Cancer Hazards on the HERP Index" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ^ IARC Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans (PDF). Vol. 73–16. 1999. pp. 307–27.

- ^ "Florida State Symbols". Florida Department of State. Division of Historical Resources.

- ^ "Definition of orange". OED online (www.oxforddictionaries.com).

- ^ Paterson, Ian (2003). A Dictionary of Colour: A Lexicon of the Language of Colour (1st paperback ed.). London: Thorogood (published 2004). p. 280. ISBN 1-85418-375-3. OCLC 60411025Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b "Multilingual Multiscript Plant Name Database: Sorting Citrus Names". University of Melbourne (www.search.unimelb.edu.au). Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ a b Robert C. Ostergren; Mathias Le Bosse (15 March 2011). The Europeans, Second Edition: A Geography of People, Culture, and Environment. Guilford Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-60918-140-6.

- ^ Template:It icon Citrus × sinensis – Wikipedia. It.wikipedia.org (2011-09-22). Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ^ Charles Duff (1 January 1971). Spanish for beginners. HarperCollins. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-06-463271-3. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ See also List of Puerto Rican slang words and phrases

- ^ Hoad, T. F. (1996). "orange". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. HighBeam Research. Retrieved May 19, 2010.