Capsaicin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

8-Methyl-N-vanillyl-(trans)-6-nonenamide

| |

| Other names

(E)-N-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzyl)

-8-methylnon-6-enamide, trans-8-Methyl-N-vanillylnon -6-enamide, (E)-Capsaicin, Capsicine, Capsicin, CPS, C | |

| Identifiers | |

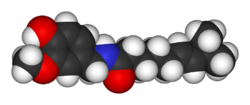

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.337 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C18H27NO3 | |

| Molar mass | 305.418 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | crystalline white powder[1] |

| Odor | highly volatile and pungent |

| Melting point | 62 °C (144 °F; 335 K) |

| Boiling point | 210 °C (410 °F; 483 K) |

| 0.0013 g/100 mL | |

| Solubility | soluble in alcohol, ether, benzene slightly soluble in CS2, HCl, petroleum |

| UV-vis (λmax) | 280 nm |

| Structure | |

| monoclinic | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Toxic (T) |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| Capsaicin | |

|---|---|

| Heat | Above Peak (SR: 15,000,000-16,000,000) |

Capsaicin (/kæpˈseɪ.[invalid input: 'ɨ']sɪn/; 8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide) is an active component of chili peppers, which are plants belonging to the genus Capsicum. It is an irritant for mammals, including humans, and produces a sensation of burning in any tissue with which it comes into contact. Capsaicin and several related compounds are called capsaicinoids and are produced as secondary metabolites by chili peppers, probably as deterrents against certain mammals and fungi.[2] Pure capsaicin is a volatile, hydrophobic, colorless, odorless, crystalline to waxy compound.

History

The compound[3] was first extracted (albeit in impure form) in 1816 by Christian Friedrich Bucholz (1770–1818).[4] He called it "capsicin", after the genus Capsicum from which it was extracted. John Clough Thresh (1850–1932), who had isolated capsaicin in almost pure form,[5][6] gave it the name "capsaicin" in 1876.[7] But it was Karl Micko who first isolated capsaicin in pure form in 1898.[8] Capsaicin's empirical formula (chemical composition) was first determined by E. K. Nelson in 1919; he also partially elucidated capsaicin's chemical structure.[9] Capsaicin was first synthesized in 1930 by E. Spath and S. F. Darling.[10] In 1961, similar substances were isolated from chili peppers by the Japanese chemists S. Kosuge and Y. Inagaki, who named them capsaicinoids.[11][12]

In 1873 German pharmacologist Rudolf Buchheim[13] (1820–1879) and in 1878 the Hungarian doctor Endre Hőgyes[14] stated that "capsicol" (partially purified capsaicin[15]) caused the burning feeling when in contact with mucous membranes and increased secretion of gastric acid.

Capsaicinoids

Capsaicin is the main capsaicinoid in chili peppers, followed by dihydrocapsaicin. These two compounds are also about twice as potent to the taste and nerves as the minor capsaicinoids nordihydrocapsaicin, homodihydrocapsaicin, and homocapsaicin. Dilute solutions of pure capsaicinoids produced different types of pungency; however, these differences were not noted using more concentrated solutions.

Capsaicin is believed to be synthesized in the interlocular septum of chili peppers by addition of a branched-chain fatty acid to vanillylamine; specifically, capsaicin is made from vanillylamine and 8-methyl-6-nonenoyl CoA.[16][17] Biosynthesis depends on the gene AT3, which resides at the pun1 locus, and which encodes a putative acyltransferase.[18]

Besides the six natural capsaicinoids, one synthetic member of the capsaicinoid family exists. Vanillylamide of n-nonanoic acid (VNA, also PAVA) is used as a reference substance for determining the relative pungency of capsaicinoids.

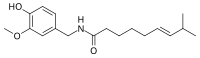

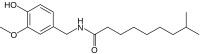

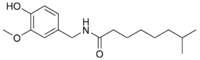

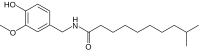

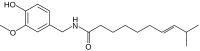

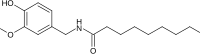

| Capsaicinoid name | Abbrev. | Typical relative amount |

Scoville heat units |

Chemical structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsaicin | C | 69% | 16,000,000 |

|

| Dihydrocapsaicin | DHC | 22% | 15,000,000 |

|

| Nordihydrocapsaicin | NDHC | 7% | 9,100,000 |

|

| Homodihydrocapsaicin | HDHC | 1% | 8,600,000 |

|

| Homocapsaicin | HC | 1% | 8,600,000 |

|

| Nonivamide | PAVA | 9,200,000 |

|

Natural function

Capsaicin is present in large quantities in the placental tissue (which holds the seeds), the internal membranes and, to a lesser extent, the other fleshy parts of the fruits of plants in the genus Capsicum. The seeds themselves do not produce any capsaicin, although the highest concentration of capsaicin can be found in the white pith of the inner wall, where the seeds are attached.[19]

The seeds of Capsicum plants are dispersed predominantly by birds: in birds, the TRPV1 channel does not respond to capsaicin or related chemicals (avian vs mammalian TRPV1 show functional diversity and selective sensitivity). This is advantageous to the plant, as chili pepper seeds consumed by birds pass through the digestive tract and can germinate later, whereas mammals have molar teeth which destroy such seeds and prevent them from germinating. Thus, natural selection may have led to increasing capsaicin production because it makes the plant less likely to be eaten by animals that do not help it reproduce.[20] There is also evidence that capsaicin may have evolved as an anti-fungal agent:[21] the fungal pathogen Fusarium, which is known to infect wild chilies and thereby reduce seed viability, is deterred by capsaicin, which thus limits this form of predispersal seed mortality.

In 2006, it was discovered that the venom of a certain tarantula species activates the same pathway of pain as is activated by capsaicin; this was the first demonstrated case of such a shared pathway in both plant and animal anti-mammal defense.[22]

Uses

Food

Because of the burning sensation caused by capsaicin when it comes in contact with mucous membranes, it is commonly used in food products to give them added spice or "heat" (piquancy). In high concentrations, capsaicin will also cause a burning effect on other sensitive areas of skin. The degree of heat found within a food is often measured on the Scoville scale. In some cases, people enjoy the heat; there has long been a demand for capsaicin-spiced food and beverages.[23] There are many cuisines and food products featuring capsaicin such as hot sauce, salsa, and beverages.

For information on treatment, see the section Treatment after exposure.

It is common for people to experience pleasurable and even euphoriant effects from ingesting capsaicin. Folklore among self-described "chiliheads" attributes this to pain-stimulated release of endorphins, a different mechanism from the local receptor overload that makes capsaicin effective as a topical analgesic. In support of this theory, there is some evidence that the effect can be blocked by naloxone and other compounds that compete for receptor sites with endorphins and opiates.[24]

Medical

Capsaicin is used as an analgesic in topical ointments, nasal sprays (Sinol-M), and dermal patches to relieve pain, typically in concentrations between 0.025% and 0.25%. It may be applied in cream form for the temporary relief of minor aches and pains of muscles and joints associated with arthritis, backache, strains and sprains, often in compounds with other rubefacients.[25] It is also used to reduce the symptoms of peripheral neuropathy such as post-herpetic neuralgia caused by shingles.[26] In direct application the treatment area is typically numbed first with a topical anesthetic; capsaicin is then applied by a therapist wearing rubber gloves and a face mask. The capsaicin remains on the skin until the patient starts to feel the "heat", at which point it is promptly removed. Capsaicin is also available in large bandages (plasters) that can be applied to the back.

Capsaicin creams are used to treat psoriasis as an effective way to reduce itching and inflammation.[27][28]

The mechanism by which capsaicin's analgesic and/or anti-inflammatory effects occurs is purportedly by mimicing a burning sensation; overwhelming the nerves by the calcium influx, and thereby rendering the nerves unable to report pain for an extended period of time. With chronic exposure to capsaicin, neurons are depleted of neurotransmitters, leading to reduction in sensation of pain and blockade of neurogenic inflammation. If capsaicin is removed, the neurons recover.[29][30][citation needed]

Capsaicin selectively binds to a protein known as TRPV1 that resides on the membranes of pain and heat-sensing neurons.[31][32] TRPV1 is a heat-activated calcium channel that opens between 37 and 45 °C (98.6 and 113 °F, respectively). When capsaicin binds to TRPV1, it causes the channel to open below 37 °C (normal human body temperature), which is why capsaicin is linked to the sensation of heat. Prolonged activation of these neurons by capsaicin depletes presynaptic substance P, one of the body's neurotransmitters for pain and heat. Neurons that do not contain TRPV1 are unaffected.

Animal and human studies have demonstrated that the oral intake of capsaicin may increase the production of heat by the body for a short time.[citation needed]

One study with human subjects indicates that capsaicin may be used to help regulate blood sugar levels by affecting carbohydrate breakdown after a meal.[33]

Rodent studies have shown that capsicum may have some effectiveness against cancer. However, the American Cancer Society warns "available scientific research does not support claims for the effectiveness of capsicum or whole pepper supplements in preventing or curing cancer at this time".[34] Other uses not supported by evidence are: "addiction, malaria, yellow fever, heart disease, stroke, weight loss, poor appetite, and sexual potency".[34]

Capsaicin is the key ingredient in the experimental drug Adlea, which is in (as of 2007) 'Phase 2 Trials' as a long-acting analgesic to treat post-surgical and osteoarthritic pain for weeks to months after a single injection to the site of pain.[35] Moreover, the drug purportedly reduces pain caused by osteoarthritis[36],joint and/or muscle pain from fibromyalgia and from other causes.

Non-lethal force

Capsaicin is also the active ingredient in riot control and personal defense pepper spray chemical agents. When the spray comes in contact with skin, especially eyes or mucous membranes, it is very painful, and breathing small particles of it as it disperses can cause breathing difficulty, which serves to discourage assailants. Refer to the Scoville scale for a comparison of pepper spray to other sources of capsaicin.

Pest deterrent

Capsaicin is also used to deter pests, specifically mammalian pests. Targets of capsaicin repellants include voles, deer, rabbits, squirrels, insects, and attacking dogs.[37] Ground or crushed dried chili pods may be used in birdseed to deter squirrels,[38] taking advantage of the insensitivity of birds to capsaicin. The Elephant Pepper Development Trust claims the use of chili peppers to improve crop security for rural African communities[citation needed]. Noteably, an article published in the Journal of Enviromental Science and Health in 2006 states that "Although hot chili pepper extract is commonly used as a component of household and garden insect-repellent formulas, it is not clear that the capsaicinoid elements of the extract are responsible for its repellency."[39]

The first pesticide product using solely capsaicin as the active ingredient was registered with the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1962.[37] There are multiple manufacturers of a capsaicin-based gel product claiming to be a feral-pigeon (Columba livia) deterrent from specific roosting and loafing areas. Some of these products have an EPA label and NSF approval[citation needed].

Equestrian sports

Capsaicin is a banned substance in equestrian sports because of its hypersensitizing and pain-relieving properties. At the show jumping events of the 2008 Summer Olympics, four horses tested positive for the substance, which resulted in disqualification.[40]

Mechanism of action

The burning and painful sensations associated with capsaicin result from its chemical interaction with sensory neurons. Capsaicin, as a member of the vanilloid family, binds to a receptor called the vanilloid receptor subtype 1 (TRPV1).[41] First cloned in 1997, TRPV1 is an ion channel-type receptor. TRPV1, which can also be stimulated with heat, protons and physical abrasion, permits cations to pass through the cell membrane and into the cell when activated. The resulting depolarization of the neuron stimulates it to signal the brain. By binding to the TRPV1 receptor, the capsaicin molecule produces similar sensations to those of excessive heat or abrasive damage, explaining why the spiciness of capsaicin is described as a burning sensation.

Early research showed capsaicin to evoke a strikingly long-onset current in comparison to other chemical agonists, suggesting the involvement of a significant rate-limiting factor.[42] Subsequent to this, the TRPV1 ion channel has been shown to be a member of the superfamily of TRP ion channels, and as such is now referred to as TRPV1. There are a number of different TRP ion channels that have been shown to be sensitive to different ranges of temperature and probably are responsible for our range of temperature sensation. Thus, capsaicin does not actually cause a chemical burn, or indeed any direct tissue damage at all, when chili peppers are the source of exposure. The inflammation resulting from exposure to capsaicin is believed to be the result of the body's reaction to nerve excitement. For example, the mode of action of capsaicin in inducing bronchoconstriction is thought to involve stimulation of C fibers [43] culminating in the release of neuropeptides. In essence, the body inflames tissues as if it has undergone a burn or abrasion and the resulting inflammation can cause tissue damage in cases of extreme exposure, as is the case for many substances that cause the body to trigger an inflammatory response.

Toxicity

Acute health effects

Capsaicin is a highly irritant material requiring proper protective goggles, respirators, and proper hazardous material-handling procedures. Capsaicin takes effect upon skin contact (irritant, sensitizer), eye contact (irritant), ingestion, and inhalation (lung irritant, lung sensitizer). The LD50 in mice is 47.2 mg/kg.[44][45]

Painful exposures to capsaicin-containing peppers are among the most common plant-related exposures presented to poison centers.[citation needed] They cause burning or stinging pain to the skin and, if ingested in large amounts by adults or small amounts by children, can produce nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and burning diarrhea. Eye exposure produces intense tearing, pain, conjunctivitis, and blepharospasm.[46]

When used for weight loss in capsules, there has been a report of heart attack; this was thought to be due to excess sympathetic output.[47]

Treatment after exposure

The primary treatment is removal from exposure. Contaminated clothing should be removed and placed in airtight bags to prevent secondary exposure.

For external exposure, bathing the mucous membrane surfaces that have contacted capsaicin with oily compounds such as vegetable oil, paraffin oil, petroleum jelly (Vaseline), creams, or polyethylene glycol is the most effective way to attenuate the associated discomfort;[citation needed] since oil and capsaicin are both hydrophobic hydrocarbons the capsaicin that has not already been absorbed into tissues will be picked up into solution and easily removed. Capsaicin can also be washed off the skin using soap, shampoo, or other detergents. Plain water is ineffective at removing capsaicin,[44] as are bleach, sodium metabisulfite and topical antacid suspensions.[citation needed] Capsaicin is soluble in alcohol, which can be used to clean contaminated items.[44]

When capsaicin is ingested, cold milk is an effective way to relieve the burning sensation (due to caseins having a detergent effect on capsaicin[48]); and room-temperature sugar solution (10%) at 20 °C (68 °F) is almost as effective.[49] The cooling sensation may, however, only be temporary, and drinking any beverage will enhance the burning sensation[citation needed] by spreading the capsaicin throughout the mouth and maximizing receptors' exposure to it, making bread or white rice a better alternative. The burning sensation will slowly fade away over several hours if no actions are taken.

Burning and pain symptoms can also be relieved by cooling, such as from ice, cold water, cold bottles, cold surfaces, or a flow of air from wind or a fan.[citation needed] In severe cases, eye burn might be treated symptomatically with topical ophthalmic anesthetics, and mucous membrane burn with lidocaine gel. The gel from the aloe plant has also been shown to be very effective.[citation needed] Capsaicin-induced asthma might be treated with nebulized bronchodilators[citation needed] or oral antihistamines or corticosteroids.[46]

Effects of dietary consumption

Ingestion of spicy food or ground jalapeño peppers does not cause mucosal erosions or other abnormalities.[50] Some mucosal microbleeding has been found after eating red and black peppers, but there was no significant difference between aspirin (used as a control) and peppers.[51] The question of whether chili ingestion increases or decreases risk of stomach cancer is mixed: a study of Mexican patients found self-reported capsaicin intake levels associated with increased stomach cancer rates (and this is independent of infection with Helicobacter pylori[52]) while a study of Italians suggests eating hot peppers regularly was protective against stomach cancer.[53] Carcinogenic, co-carcinogenic, and anticarcinogenic effects of capsaicin have been reported in animal studies.[54][55]

Effects on weight loss and regain

There is no evidence showing that weight loss is directly correlated with ingesting capsaicin, but there is a positive correlation between ingesting capsaicin and a decrease in weight regain. The effects of capsaicin are said to cause "a shift in substrate oxidation from carbohydrate to fat oxidation".[56] This leads to a decrease in appetite as well as a decrease in food intake.[56] Even though ingestion of capsaicin causes thermogenesis, the increase in body temperature does not affect weight loss. However, both oral and gastrointestinal exposure to capsaicin increases satiety and reduces energy as well as fat intake.[57] Oral exposure proves to yield stronger reduction suggesting that capsaicin has sensory effects. Short-term studies suggest that capsaicin aids in the decrease of weight regain. However, long-term studies are limited because of the pungency of capsaicin.[58] Another recent study has suggested that the ingestion of capsaicinoids can increase energy expenditure and fat oxidation through the activation of brown adipose tissue (BAT) in humans from the effects of the capsaicin.[59]

See also

- Allicin, the active piquant flavor chemical in uncooked garlic, and to a lesser extent onions (see those articles for discussion of other chemicals in them relating to pungency, and eye irritation)

- Allyl isothiocyanate, the active piquant chemical in mustard, radishes, horseradish, and wasabi

- Capsazepine, capsaicin antagonist

- Capsinoids, similar in structure to capsaicin, but lack the extreme pungency, and density

- Discovery and development of TRPV1 antagonists

- Gingerol and shogaol, the active piquant flavor chemicals in ginger

- Naga Viper pepper, Bhut Jolokia Pepper, Carolina Reaper, Trinidad Moruga Scorpion; some of the world's most capsaicin-rich fruits

- Piperine, the active piquant chemical in black pepper

- Scoville scale, a measurement of the spicy heat (or pungency) of a chili pepper

- Sinus Buster, a patent medicine containing capsaicin

- syn-Propanethial-S-oxide, the major active piquant chemical in onions

- TRPV1, the only known receptor (a transient receptor potential channel) for capsaicin

References

Footnotes

- ^ ChemSpider - Capsaicin

- ^ What Made Chili Peppers So Spicy? Talk of the Nation, 15 August 2008.

- ^ History of early research on capsaicin:

- Harvey W. Felter and John U. Lloyd, King's American Dispensatory (Cincinnati, Ohio: Ohio Valley Co., 1898), vol. 1, page 435. Available on-line at: Henriette's Herbal.

- Andrew G. Du Mez, "A century of the United States pharmocopoeia 1820-1920. I. The galenical oleoresins" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, 1917), pages 111-132. Available on-line at: Archive.org.

- ^ See:

- C. F. Bucholz (1816) "Chemische Untersuchung der trockenen reifen spanischen Pfeffers" [Chemical investigation of dry, ripe Spanish peppers], Almanach oder Taschenbuch für Scheidekünstler und Apotheker (Weimar) [Almanac or Pocket-book for Analysts (Chemists) and Apothecaries], vol. 37, pages 1-30. [Note: Christian Friedrich Bucholz's surname has been variously spelled as "Bucholz", "Bucholtz", or "Buchholz".]

- The results of Bucholz's and Braconnot's analyses of Capsicum annuum appear in: Jonathan Pereira, The Elements of Materia Medica and Therapeutics, 3rd U.S. ed. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Blanchard and Lea, 1854), vol. 2, page 506.

- Biographical information about Christian Friedrich Bucholz is available in: Hugh J. Rose, Henry J. Rose, and Thomas Wright, ed.s, A New General Biographical Dictionary (London, England: 1857), vol. 5, page 186.

- Biographical information about C. F. Bucholz is also available (in German) on-line at: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie.

- Some other early investigators who also extracted the active component of peppers:

- Benjamin Maurach (1816) "Pharmaceutisch-chemische Untersuchung des spanischen Pfeffers" (Pharmaceutical-chemical investigation of Spanish peppers), Berlinisches Jahrbuch für die Pharmacie, vol. 17, pages 63-73. Abstracts of Maurach's paper appear in: (i) Repertorium für die Pharmacie, vol. 6, page 117-119 (1819); (ii) Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, vol. 4, no. 18, page 146 (Feb. 1821); (iii) "Spanischer oder indischer Pfeffer", System der Materia medica ... , vol. 6, pages 381-386 (1821) (this reference also contains an abstract of Bucholz's analysis of peppers).

- French chemist Henri Braconnot (1817) "Examen chemique du Piment, de son principe âcre, et de celui des plantes de la famille des renonculacées" (Chemical investigation of the chili pepper, of its pungent principle [constituent, component], and of that of plants of the family Ranunculus), Annales de Chemie et de Physique, vol. 6, pages 122- 131.

- Danish geologist Johann Georg Forchhammer in: Hans C. Oersted (1820) "Sur la découverte de deux nouveaux alcalis végétaux" (On the discovery of two new plant alkalis), Journal de physique, de chemie, d'histoire naturelle et des arts, vol. 90, pages 173-174.

- German apothecary Ernst Witting (1822) "Considerations sur les bases vegetales en general, sous le point de vue pharmaceutique et descriptif de deux substances, la capsicine et la nicotianine" (Thoughts on the plant bases in general from a pharmaceutical viewpoint, and description of two substances, capsicin and nicotine), Beiträge für die pharmaceutische und analytische Chemie, vol. 3, pages 43ff.

- ^ In a series of articles, J. C. Thresh obtained capsaicin in almost pure form:

- J. C. Thresh (1876) "Isolation of capsaicin," The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions, 3rd series, vol. 6, pages 941-947;

- J. C. Thresh (8 July 1876) "Capsaicin, the active principle in Capsicum fruits," The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions, 3rd series, vol. 7, no. 315, pages 21 ff. [Note: This article is summarized in: "Capsaicin, the active principle in Capsicum fruits," The Analyst, vol. 1, no. 8, pages 148-149, (1876).]. In The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions, volume 7, see also pages 259ff and 473 ff and in vol. 8, see pages 187ff;

- Year Book of Pharmacy… (1876), pages 250 and 543;

- J. C. Thresh (1877) "Note on Capsaicin," Year Book of Pharmacy…, pages 24-25;

- J. C. Thresh (1877) "Report on the active principle of Cayenne pepper," Year Book of Pharmacy..., pages 485-488.

- ^ Obituary notice of J. C. Thresh: "John Clough Thresh, M.D., D. Sc., and D.P.H.," The British Medical Journal, vol. 1, no. 3726, pages 1057-1058 (4 June 1932).

- ^ J King, H Wickes Felter, J Uri Lloyd (1905) A King's American Dispensatory. Eclectic Medical Publications (ISBN 1888483024)

- ^ Karl Micko (1898) "Zur Kenntniss des Capsaïcins" (On our knowledge of capsaicin), Zeitschrift für Untersuchung der Nahrungs- und Genussmittel (Journal for the Investigation of Necessities and Luxuries), vol. 1, pages 818-829. See also: Karl Micko (1899) "Über den wirksamen Bestandtheil des Cayennespfeffers" (On the active component of Cayenne pepper), Zeitschrift für Untersuchung der Nahrungs- und Genussmittel, vol. 2, pages 411-412.

- ^ E. K. Nelson. "The constitution of capsaicin, the pungent principle of capsicum". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1919, 41, 1115–1121. {{|10.1021/ja02228a011}}

- ^ Ernst Späth, Stephen F. Darling. Synthese des Capsaicins. Chem. Ber. 1930, 63B, 737–743.

- ^ S Kosuge, Y Inagaki, H Okumura (1961). Studies on the pungent principles of red pepper. Part VIII. On the chemical constitutions of the pungent principles. Nippon Nogei Kagaku Kaishi (J. Agric. Chem. Soc.), 35, 923–927; (en) Chem. Abstr. 1964, 60, 9827g.

- ^ (ja) S Kosuge, Y Inagaki (1962) Studies on the pungent principles of red pepper. Part XI. Determination and contents of the two pungent principles. Nippon Nogei Kagaku Kaishi (J. Agric. Chem. Soc.), 36, pp. 251

- ^ Rudolf Buchheim (1873) "Über die 'scharfen' Stoffe" (On the "hot" substance), Archiv der Heilkunde (Archive of Medicine), vol. 14, pages 1ff. See also: R. Buchheim (1872) "Fructus Capsici," Vierteljahresschrift fur praktische Pharmazie (Quarterly Journal for Practical Pharmacy), vol. 4, pages 507ff.; reprinted (in English) in: Proceedings of the American Pharmaceutical Association, vol. 22, pages 106ff (1873).

- ^ Endre Hőgyes, "Adatok a paprika (Capsicum annuum) élettani hatásához" [Data on the physiological effects of the pepper (Capsicum annuum)], Orvos-természettudumányi társulatot Értesítője [Bulletin of the Medical Science Association] (1877); reprinted in: Orvosi Hetilap [Medical Journal] (1878), 10 pages. Published in German as: "Beitrage zur physiologischen Wirkung der Bestandtheile des Capiscum annuum (Spanischer Pfeffer)" [Contributions on the physiological effects of components of Capsicum annuum (Spanish pepper)], Archiv für Experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie, vol. 9, pages 117-130 (1878). See: http://www.springerlink.com/content/n54508568351x051/ .

- ^ F.A. Flückiger, Pharmakognosie des Pflanzenreiches ( Berlin, Germany: Gaertner's Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1891).

- ^ Fujiwake H., Suzuki T., Oka S., Iwai K. (1980). "Enzymatic formation of capsaicinoid from vanillylamine and iso-type fatty acids by cell-free extracts of Capsicum annuum var. annuum cv. Karayatsubusa". Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 44: 2907–2912. doi:10.1271/bbb1961.44.2907.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ I. Guzman, P.W. Bosland, and M.A. O'Connell, "Chapter 8: Heat, Color, and Flavor Compounds in Capsicum Fruit" in David R. Gang, ed., Recent Advances in Phytochemistry 41: The Biological Activity of Phytochemicals (New York, New York: Springer, 2011), pages 117-118.

- ^ Stewart C, Kang BC, Liu K; et al. (June 2005). "The Pun1 gene for pungency in pepper encodes a putative acyltransferase". Plant J. 42 (5): 675–88. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02410.x. PMID 15918882.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ New Mexico State University - College of Agriculture and Home Economics (2005). "Chile Information - Frequently Asked Questions". Archived from the original on May 4, 2007. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/35086653, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/35086653instead. - ^ Joshua J. Tewksbury, Karen M. Reagan, Noelle J. Machnicki, Tomás A. Carlo,

David C. Haak, Alejandra Lorena Calderón Peñaloza, and Douglas J. Levey (2008-08-19), "Evolutionary ecology of pungency in wild chilies", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105 (33): 11808–11811, doi:10.1073/pnas.0802691105, retrieved 2010-06-30

{{citation}}: line feed character in|author=at position 75 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Siemens J, Zhou S, Piskorowski R; et al. (November 2006). "Spider toxins activate the capsaicin receptor to produce inflammatory pain". Nature. 444 (7116): 208–12. doi:10.1038/nature05285. PMID 17093448.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ A Perk of Our Evolution: Pleasure in Pain of Chilies, New York Times, September 20, 2010

- ^ Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. - The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine - 8(3):341

- ^ Topical capsaicin for pain relief

- ^ "Which Treatment for Postherpetic Neuralgia?". PLoS Medicine. 2 (7). PLoS Med: e238. July 2005. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020238.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Glinski W, Glinska-Ferenz M, Pierozynska-Dubowska M. (1991). "Neurogenic inflammation induced by capsaicin in patients with psoriasis". Acta dermato-venereologica. 71 (1). Acta Derm Venereol.: 51–4. PMID 1711752.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arnold WP, van de Kerkhof PC. (September 1993). "Topical capsaicin in pruritic psoriasis". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 29 (3). J Am Acad Dermatol.: 438–42. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70208-B. PMID 8021363.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18307678, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18307678instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18635498, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18635498instead. - ^ Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D (October 1997). "The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway". Nature. 389 (6653): 816–24. doi:10.1038/39807. PMID 9349813.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "How Hot is Hot? A Burning Question About a Hot Condiment". The Lipid Chronicles. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ^ Lejeune MP, Kovacs EM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. (September 2003). "Effect of capsaicin on substrate oxidation and weight maintenance after modest body-weight loss in human subjects". The British journal of nutrition. 90 (3). Br J Nutr.: 651–59. doi:10.1079/BJN2003938. PMID 13129472.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Capsicum". Amrerican Cancer Society. 2008-11-30. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

- ^ "Doctors Test Hot Sauce For Pain Relief". Retrieved 2007-10-30.[dead link]

- ^ Liana Fraenkel; Sidney T. Bogardus Jr; John Concato; Dick R. Wittink (June 2004). "Treatment Options in Knee Osteoarthritis: The Patient's Perspective". 164 (12). Arch Intern Med,: 1299–1304.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "R.E.D. Facts for Capsaicin" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2012-11-13. Cite error: The named reference "EPA facts capsaicin" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12974352, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12974352instead. - ^ Antonious GF, Meyer JE, Snyder JC (2006). "Toxicity and repellency of hot pepper extracts to spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch". J Environ Sci Health B. 41 (8): 1383–91. doi:10.1080/0360123060096419. PMID 17090499.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Olympic horses fail drugs tests". BBC News. 2008-08-21. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- ^ Story GM, Crus-Orengo L (July–August 2007). "Feel the burn". American Scientist. 95 (4): 326–333. doi:10.1511/2007.66.326.

- ^ Geppetti, Pierangelo & Holzer, Peter (1996). Neurogenic Inflammation. CRC Press, 1996.

- ^ Fuller, R. W., Dixon, C. M. S. & Barnes, P. J. (1985). Bronchoconstrictor response to inhaled capsaicin in humans" J. Appl. Physiol 58, 1080–1084. PubMed, CAS, Web of Science® Times Cited: 174

- ^ a b c "Capsaicin Material Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). sciencelab.com. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- ^ Johnson, Wilbur (2007). "Final report on the safety assessment of capsicum annuum extract, capsicum annuum fruit extract, capsicum annuum resin, capsicum annuum fruit powder, capsicum frutescens fruit, capsicum frutescens fruit extract, capsicum frutescens resin, and capsaicin". Int. J. Toxicol. 26 Suppl 1: 3–106. doi:10.1080/10915810601163939. PMID 17365137.

- ^ a b Goldfrank, L R. (ed.). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 1167. ISBN 0-07-144310-X.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Sayin MR, et al. A case of acute myocardial infarction due to the use of cayenne pepper pills. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift-The Central European Journal of Medicine (2012) 124:285-287

- ^ General Chemistry Online: Fire and Spice

- ^ Temporal effectiveness of mouth-rinsing on capsaicin mouth-burn. Christina Wu Nasrawia and Rose Marie Pangborn. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0031-9384(90)90067-E

- ^ Graham DY, Smith JL, Opekun AR.; Smith; Opekun (1988). "Spicy food and the stomach. Evaluation by videoendoscopy". JAMA. 260 (23): 3473–5. doi:10.1001/jama.260.23.3473. PMID 3210286.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Myers BM, Smith JL, Graham DY (March 1987). "Effect of red pepper and black pepper on the stomach". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 82 (3): 211–4. PMID 3103424.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ López-Carrillo L, López-Cervantes M, Robles-Díaz G; et al. (2003). "Capsaicin consumption, Helicobacter pylori positivity and gastric cancer in Mexico". Int. J. Cancer. 106 (2): 277–82. doi:10.1002/ijc.11195. PMID 12800206.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Buiatti; Palli, D; Decarli, A; Amadori, D; Avellini, C; Bianchi, S; Bonaguri, C; Cipriani, F; et al. (May 1990). "A case-control study of gastric cancer and diet in Italy: II. Association with nutrients". [Int J Cancer]. 45 (5): 896–901. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910450520. PMID 2335393.

- ^ Johnson, Wilbur (2007). "Final report on the safety assessment of capsicum annuum extract, capsicum annuum fruit extract, capsicum annuum resin, capsicum annuum fruit powder, capsicum frutescens fruit, capsicum frutescens fruit extract, capsicum frutescens resin, and capsaicin". Int. J. Toxicol. 26 Suppl 1: 3–106. doi:10.1080/10915810601163939. PMID 17365137.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21487045, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21487045instead. - ^ a b Lejeune, Manuela P. G. M., Eva M. R. Kovacs, and Margriet S. Westerterp- Plantenga. "Effect of Capsaicin on Substrate Oxidation and Weight Maintenance after Modest Body-weight Loss in Human Subjects." British Journal of Nutrition 90.03 (2003): 651.

- ^ Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S., A. Smeets, and M P G. Lejeune. "Sensory and Gastrointestinal Satiety Effects of Capsaicin on Food Intake." International Journal of Obesity 29.6 (2004): 682-88.

- ^ Diepvens, K., K. R. Westerterp, and M. S. Westerterp-Plantenga. "Obesity and Thermogenesis Related to the Consumption of Caffeine, Ephedrine, Capsaicin, and Green Tea." AJP: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 292.1 (2006): R77-85.

- ^ Yoneshiro, Takeshi, Sayuri Aita, Yuko Kawai, Toshihiko Iwanaga, and Mayayuki Saito. "Nonpungent Capsaicin Analogs (capsinoids) Increase Energy Expenditure through the Activation of Brown Adipose Tissue in Humans." American Society for Nutrition (2012).

General references

- Dray A (1992). "Mechanism of action of capsaicin-like molecules on sensory neurons". Life Sci. 51 (23): 1759–65. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(92)90045-Q. PMID 1331641.

- Garnanez RJ, McKee LH (2001) "Temporal effectiveness of sugar solutions on mouth burn by capsaicin" IFT Annual Meeting 2001

- Henkin R (November 1991). "Cooling the burn from hot peppers". JAMA. 266 (19): 2766. doi:10.1001/jama.266.19.2766b. PMID 1942431.

- Nasrawi CW, Pangborn RM (April 1990). "Temporal effectiveness of mouth-rinsing on capsaicin mouth-burn". Physiol. Behav. 47 (4): 617–23. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(90)90067-E. PMID 2385629.

- Tewksbury JJ, Nabhan GP (July 2001). "Seed dispersal. Directed deterrence by capsaicin in chilies". Nature. 412 (6845): 403–4. doi:10.1038/35086653. PMID 11473305.

- Kirifides ML, Kurnellas MP, Clark L, Bryant BP (February 2004). "Calcium responses of chicken trigeminal ganglion neurons to methyl anthranilate and capsaicin". J. Exp. Biol. 207 (Pt 5): 715–22. doi:10.1242/jeb.00809. PMID 14747403.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tarantula Venom, Chili Peppers Have Same "Bite," Study Finds http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/11/061108-tarantula-venom.html

- Minna M. Hamalainen, Alberto Subieta, Christopher Arpey, Timothy J. Brennan, "Differential Effect of Capsaicin Treatment on Pain-Related Behaviors After Plantar Incision," The Journal of Pain, 10,6 (2009), 637-645.

External links

- Capsaicin Technical Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- EPA Capsaicin Reregistration Eligibility Decision Fact Sheet

- Molecule of the Month

- European Commission, opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on capsaicin.

- Fire and Spice: The molecular basis for flavor

- A WikiHow article on How to Cool Chilli Pepper Burns.