Concurrency (road)

A concurrency in a road network is an instance of one physical road bearing two or more different highway, motorway, or other route numbers.[1] When two freeways share the same right-of-way, it is sometimes called a common section or commons.[2] Other terminology for a concurrency includes overlap,[3] coincidence,[4] duplex (two concurrent routes), triplex (three concurrent routes) and multiplex (any number of concurrent routes).[5]

Concurrent numbering can become very common in countries that allow it. Where multiple routes must pass through a single mountain crossing, or through a major city, it is often economically and practically advantageous for them all to be accommodated on a single physical road. In some countries, however, concurrent numbering is avoided by posting only one route number on road signs; these routes disappear at the start of the concurrency and reappear when it ends. Criticism of concurrencies include environmental intrusion,[6] as well as being considered a factor in road accidents.[7]

Overview

Most concurrencies are simply a combination of two route numbers on the same physical road. This is often practically advantageous as well as economically advantageous; it may be better for two route numbers to be combined into one along riverways or through mountain valleys. Some nations allow for concurrencies to occur, however some nations specifically do not allow it to happen. In those nations which do permit concurrencies, it can become very common. In these countries, there are a variety of concurrences which can occur.

An example of this is the concurrency of I-70 and I-76 on the Pennsylvania Turnpike in western Pennsylvania. Interstate 70 merges with the Pennsylvania Turnpike so the route number can ultimately continue east into Maryland; instead of having a second physical highway built to carry the route, it is combined with the Pennsylvania Turnpike and the Interstate 76 designation.[8] A triple Interstate concurrency is found north of Madison, Wisconsin, with I-39, I-90, and I-94.[9] Wisconsin has another triple Interstate concurrency along the five-mile (8.0 km) section of I-41, I-43, and I-894 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[10] The concurrency of I-41 and I-43 on this roadway is an example of a wrong-way concurrency.

The longest Interstate highway concurrency is I-80 and I-90 for 265 miles (426 km) across Indiana and Ohio.[11]

There is an example of an eight-way concurrency: I-465 around Indianapolis and Georgia State Route 10 Loop around downtown Athens, Georgia. Portions of the 53-mile (85 km) I-465 overlap with I-74, US 31, US 36, US 40, US 52, US 421, SR 37 and SR 67—a total of eight other routes. Seven of the eight other designations overlap between exits 46 and 47 to create an eight-way concurrency.[12]

Regional examples

North America

In the United States, concurrencies are simply marked by placing signs for both routes on the same or adjacent posts. The federal Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices prescribes that when mounting these adjacent signs together that the numbers will be arranged vertically or horizontally in order of precedence. The order to be used is Interstate Highways, U.S. Highways, state highways, and finally county roads, and within each class by increasing numerical value.[13]

Several states do not officially have any concurrencies, instead officially ending routes on each side of one.[a] There are several circumstances where unusual concurrencies exist along state borders. One example occurs along the Oklahoma–Arkansas state line. At the northern end of this border Oklahoma State Highway 20 runs concurrently with Arkansas Highway 43 and the two roads run north–south along the boundary.[15]

Concurrencies are also found in Canada. In Manitoba, the Trans-Canada Highway from Winnipeg to Portage la Prairie is concurrently signed with Yellowhead Highway.[16] In Ontario, the Queen Elizabeth Way and Highway 403 run concurrently between Burlington and Oakville, forming the province's only concurrency between two 400-series highways.[17]

Europe

In the United Kingdom, major through routes do not run concurrently with others.

In Sweden and Denmark, the most important highways use only the European route numbers, which have cardinal directions. In Sweden the E6 and E20 run concurrently for 280 kilometres (170 mi). In Denmark the E47 and E55 run concurrently for 157 kilometres (98 mi). There are more shorter concurrencies. There are two stretches in Sweden and Denmark where three European routes run concurrently; these are E6, E20 and E22 in Sweden, and E20, E47 and E55 in Denmark. Along all these concurrencies, all route numbers are signposted.[18]

In the Czech Republic, the European route numbers are only additional and are always concurrent with the state route numbering, usually highways or first-class roads. In the state numbering system, concurrences exist only in first-class and second-class roads; third class roads do not have them. The local term for such concurrences is [peáž] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (somehow derrived from the French word [péage] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)). In the road register, one of the roads is considered as the main ("source") road and the others as the péaging (guest) roads. The official road map enables a maximum of five concurrent routes of the intrastate numbering system.[19] Cycling routes and hiking routes are often concurrent.

The Middle East

In Israel, two freeways, the Trans-Israel Highway (Highway 6), and Highway 1 run concurrently just east of Ben Shemen Interchange. The concurrency is officially designated "Daniel Interchange", providing half of the possible interchange directions. It is a 1-mile (1.6 km) segment consisting of eight lanes providing high-speed access between the two highways. Access from Highway 1 west to Highway 6 south and Highway 6 north to Highway 1 east is provided via Route 431, while access between Highway 1 east to Highway 6 north and Highway 6 south to Highway 1 west are provided at Ben Shemen Interchange. The other movements are provided through the concurrency.[20]

Wrong-way concurrencies

As highways in the United States and Canada are usually signed with assigned cardinal direction based on primary orientation, it is possible for a stretch of roadway shared between two highways to be signed with opposite, conflicting cardinal directions. Wrong-way concurrency refers to this situation. The road itself is likely to be actually pointed in a third direction. For example, near Wytheville, Virginia, there is a concurrency between I-77 (which runs primarily north–south, as it is signed) and Interstate 81 (which runs primarily northeast-southwest but is also signed north-south). The road itself is oriented east-west and carries the two Interstates signed in opposite directions. So one might simultaneously be on I-77 north and I-81 south, while actually traveling due west.[21]

An unusual example of a three-directional concurrency occurs near the town of Starks, Illinois. To take advantage of an underpass beneath a railroad, US Route 20, Illinois Route 72 and Illinois Route 47 all converge. The net result is that a driver can be traveling east on US 20, west on IL 72, and south on IL 47 (the actual compass direction) all at the same time.[22]

Effect on exit numbers

Often when two routes with exit numbers overlap, one of the routes has its exit numbers dominate over the other and can sometimes result in having two exits of the same number, albeit far from each other along the same highway (although in one case the number 96 is only six miles apart). An example of this is from the concurrency of I-94 and US 127 near Jackson, Michigan. The concurrent section of freeway has an exit with M-106, which is numbered Exit 139 using I-94's mileage-based numbers. US 127 also has another Exit 139 with the southern end of the US 127 business loop in Mount Pleasant, Michigan.[23]

However, there are also instances where the dominant exit number range is far more than the secondary route's highest exit number, for example the concurrency of I-75 and I-85 in Atlanta, Georgia—where I-75 is dominant—the exit numbers range from 242 to 251 while I-85's highest mile marker in Georgia is 179.[24]

Consolidation plans

Some brief concurrencies in the past have been eliminated by reassigning the designations along the roadways. This can involve scaling back the terminus of one designation to the end of a concurrent section. At the same time, there could be an extension of another highway designation that is used to replace the newly shortened designation with another one.

Between states, US 27 in Michigan previously ran concurrently with I-69 from the Michigan–Indiana state line to the Lansing, Michigan, area. From there it turned northwards to its terminus at Grayling. In 1999, the Michigan and Indiana departments of transportation petitioned the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials for permission to truncate US 27 at Fort Wayne, Indiana.[25] In 2002, Michigan removed the US 27 designation from I-69 and extended the US 127 designation from Lansing to Grayling.[26] MDOT's stated reason for the modification was to "reduce confusion along the US 27/US 127 corridor".[27] After US 27's signage was removed, the highway north of the Lansing area was renumbered US 127, and the US 27 designation was removed from I-69.[27]

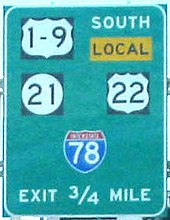

Some consolidation schemes involve the use of incorporating two single-digit numbers onto one marker, as along the U.S. Route 1/9 concurrency in northern New Jersey.[28] In the mid-20th century, California had numerous concurrencies, but the California Legislature removed most of them in a comprehensive reform of highway numbering in 1964.[29]

See also

Notes

- ^ Arkansas's highways exist in many officially designated "sections" rather than form concurrencies. Arkansas Highway 131 exists in five sections as an example.[14]

References

- ^ Staff (March 4, 2014). "Realigning Concurrent Routes". ArcGIS Help 10.2 & 10.2.1. Esri. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ "Freeway flaws; Fixing them may take decades". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. June 3, 2005.

common sections ... 2 freeways share a single right-of-way

- ^ Staff (December 19, 2012). "Realigning Overlapping Routes". ArcGIS Resource Center. Esri. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ Office of Highway System Engineering (August 1995). "State Highway Routes Selected Information, 1994 with 1995 Revisions" (PDF). California Department of Transportation. Route 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 16, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

Coincident with Rte 299

- ^ Reichard, Timothy. "Guide to Highway Multiplexes". Central PA/MD Roads. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ "Reducing Sign Clutter" (PDF). Traffic Advisory Leaflet 01/13. Department for Transport. January 2013.

- ^ Ho, Geoffrey; Scialfa, Charles T.; Caird, Jeff K.; Graw, Trevor (Summer 2001). "Visual Search for Traffic Signs: The Effects of Clutter, Luminance, and Aging". Human Factors. 43 (2): 194–207. doi:10.1518/001872001775900922. ISSN 0018-7208. PMID 11592661.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Geographic Information Section (2010). Tourism & Transportation Map (Map). Scale not given. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Department of Transportation. §§ E10–L11.

- ^ Office of Public Affairs (August 17, 2010). "Wisconsin Highway Trivia". Wisconsin Department of Transportation. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ Srubas, Paul (April 9, 2015). "It's Officially Interstate 41 Now in Wisconsin". Green Bay Press-Gazette. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ Staff (December 31, 2013). "Table 1: Main Routes of the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways as of December 31, 2013". Route Log and Finder List. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ Indiana Department of Transportation (2007). Indiana Transportation Map (Map) (2007–08 ed.). Scale not given. Indianapolis: Indiana Department of Transportation. Indianapolis inset.

- ^ Staff (2009). "Chapter 2D. Guide Signs: Conventional Roads, §2D.29: Route Sign Assemblies" (PDF). Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (Revisions 1&2, 2009 ed.). Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. p. 148. ISBN 9781615835171.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|chapter-format=requires|chapter-url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Planning and Research Division (April 2010). State Highways 2009 (ZIP) (Database). Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department Planning and Research Division (2010). State Highway Map (Map). 1 in=15 mi. Little Rock: Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department. § A1.

- ^ Manitoba Ministry Infrastructure and Transportation (2012). Official Highway Map / Carte Routière Officielle (Map). Scale not given (in English and French). Winnipeg: Manitoba Ministry Infrastructure and Transportation. §§ D2–E2.

- ^ Ministry of Transportation of Ontario Geomatics Office (2010). Official Road Map / Carte Routière (Map) (2010–11 ed.). 1:250,000 (in English and French). Toronto: Ministry of Transportation of Ontario. § R25.

- ^ Check Google Streetview at 55°33′00″N 13°03′06″E / 55.5500993°N 13.0517037°E, 55°34′48″N 12°15′42″E / 55.5800398°N 12.2615534°E and neighboring locations[full citation needed]

- ^ Číslo peažující silnice, explanatory notes to the road map, Ředitelství silnic a dálnic (Directorate of Roads and Highways)

- ^ עורכת אחראית אלנה בלינקי; Elena Belinki (2014). 2014 אטלס הזהב [Atlas HaZahav 2014] (in Hebrew) (9th ed.). מפה הוצאה לאור [Mapa Publishing]. ISBN 978-965-521-136-8.

- ^ Virginia Department of Transportation (2012). Official State Transportation Map (Map) (2012–14 ed.). 1 in≈13 mi. Richmond: Virginia Department of Transportation. §§ F6–G6.

- ^ Staff. Sign for US 30, Route 47 and Route 72 (Highway guide sign). Starks, IL: Illinois Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (2013). Pure Michigan: State Transportation Map (Map). c. 1:975,000. Lansing: Michigan Department of Transportation. §§ J10, M11. OCLC 42778335, 861227559.

- ^ Georgia Department of Transportation (2011). Official Highway and Transportation Map (Map) (2011–12 ed.). Scale not given. Atlanta: Georgia Department of Transportation. Main map, §§ B1, I2; Atlanta inset, § E5.

- ^ Special Committee on U.S. Route Numbering (April 17, 1999). "Report of the Special Committee on U.S. Route Numbering to the Standing Committee on Highways" (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- ^ Ranzenberger, Mark (April 27, 2008). "US 127 Signs Getting Updated". The Morning Sun. Mount Pleasant, MI. pp. 1A, 6A. OCLC 22378715. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Debnar, Kari; Bott, Mark (January 14, 2002). "US 27 Designation Soon To Be Deleted from Michigan Highways" (PDF) (Press release). Michigan Department of Transportation.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff. Signage for US 1/9, NJ 21, US 22, and I-78 (Highway guide sign). Newark, NJ: New Jersey Department of Transportation. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ "Route Renumbering: New Green Markers Will Replaces Old Shields" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. 43 (1–2): 11–14. March–April 1964. ISSN 0008-1159. Retrieved March 8, 2012.