Exeter Cathedral

| Exeter Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of Saint Peter | |

| |

| 50°43′21″N 3°31′48″W / 50.7224°N 3.5299°W | |

| Location | Exeter, Devon |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Tradition | Anglo-Catholic |

| Website | www |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Previous cathedrals | 2 |

| Style | Norman, Gothic |

| Years built | 1112-1400 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 383 feet (117 m) [1] |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Exeter (since 1050) |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Robert Atwell |

| Dean | Jonathan Greener |

| Precentor | vacant (acting: Martin Shaw) |

| Canon Chancellor | vacant |

| Canon(s) | Mike Williams (SSM) Becky Totterdell (DDO) |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Timothy Noon |

| Organist(s) | Timothy Parsons, Assistant Director of Music |

Exeter Cathedral, properly known as the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter in Exeter, is an Anglican cathedral, and the seat of the Bishop of Exeter, in the city of Exeter, Devon, in South West England. The present building was complete by about 1400, and has several notable features, including an early set of misericords, an astronomical clock and the longest uninterrupted vaulted ceiling in England.

History

The founding of the cathedral at Exeter, dedicated to Saint Peter, dates from 1050, when the seat of the bishop of Devon and Cornwall was transferred from Crediton because of a fear of sea-raids. A Saxon minster already existing within the town (and dedicated to Saint Mary and Saint Peter) was used by Leofric as his seat, but services were often held out of doors, close to the site of the present cathedral building.

In 1107 William Warelwast, a nephew of William the Conqueror, was appointed to the see, and this was the catalyst for the building of a new cathedral in the Norman style. Its official foundation was in 1133, during Warelwast's time, but it took many more years to complete.[2] Following the appointment of Walter Bronescombe as bishop in 1258, the building was already recognized as outmoded, and it was rebuilt in the Decorated Gothic style, following the example of Salisbury. However, much of the Norman building was kept, including the two massive square towers and part of the walls. It was constructed entirely of local stone, including Purbeck Marble. The new cathedral was complete by about 1400, apart from the addition of the chapter house and chantry chapels.

Like most English cathedrals, Exeter suffered during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, but not as much as it would have done had it been a monastic foundation. Further damage was done during the Civil War, when the cloisters were destroyed. Following the restoration of Charles II, a new pipe organ was built in the cathedral by John Loosemore. Charles II's sister Henrietta Anne of England was baptised here in 1644. During the Victorian era, some refurbishment was carried out by George Gilbert Scott. As a boy, the composer Matthew Locke was trained in the choir of Exeter Cathedral, under Edward Gibbons, the brother of Orlando Gibbons. His name can be found scribed into the stone organ screen.

During the Second World War, Exeter was one of the targets of a German air offensive against British cities of cultural and historical importance, which became known as the "Baedeker Blitz". On 4 May 1942 an early-morning air raid took place over Exeter. The cathedral sustained a direct hit by a large high-explosive bomb on the chapel of St James, completely demolishing it. The muniment room above, three bays of the aisle and two flying buttresses were also destroyed in the blast. The medieval wooden screen opposite the chapel was smashed into many pieces by the blast, but it has been reconstructed and restored.[3] Many of the cathedral's most important artifacts, such as the ancient glass (including the great east window), the misericords, the bishop's throne, the Exeter Book, the ancient charters (of King Athelstan and Edward the Confessor) and other precious documents from the library had been removed in anticipation of such an attack. The precious effigy of Walter Branscombe had been protected by sand bags.[4] Subsequent repairs and the clearance of the area around the western end of the building uncovered portions of earlier structures, including remains of the Roman city and of the original Norman cathedral.

Notable features

Notable features of the interior include the misericords, the minstrels' gallery, the astronomical clock and the organ. Notable architectural features of the interior include the multiribbed ceiling and the compound piers in the nave arcade.[5]

The 18-metre-high (59 ft) bishop's throne in the choir was made from Devon oak between 1312 and 1316; the nearby choir stalls were made by George Gilbert Scott in the 1870s. The Great East Window contains much 14th-century glass, and there are over 400 ceiling bosses, one of which depicts the murder of Thomas Becket. The bosses can be seen at the peak of the vaulted ceiling, joining the ribs together.[6] Because there is no centre tower, Exeter Cathedral has the longest uninterrupted medieval vaulted ceiling in the world, at about 96 m (315 ft).[3]

-

The nave looking east toward the organ

-

The choir looking east from the organ toward the Lady Chapel

-

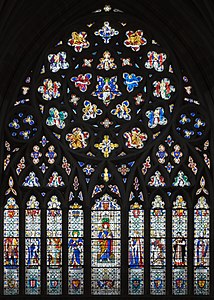

The Great East Window

-

The West Window

Misericords

The fifty misericords are the earliest complete set in the United Kingdom.[7] They date from two periods: 1220–1230 and 1250–1260. Amongst other things, they depict the earliest known wooden representation of an elephant in the UK. They have supporters.

Minstrels' gallery

The minstrels' gallery in the nave dates to around 1360 and is unique in English cathedrals. Its front is decorated with 12 carved and painted angels playing medieval musical instruments, including the cittern, bagpipe, hautboy, crwth, harp, trumpet, organ, guitar, tambourine and cymbals, with two others which are uncertain.[8] Since the above list was compiled in 1921, research among musicologists has revised how some of the instruments are called in modern times. Using revised names, the list should now read from left to right gittern, bagpipe, shawm, vielle, harp, jew's harp, trumpet, organ, citole, recorder, tambourine, cymbals.[9]

Astronomical clock

The Exeter Cathedral Astronomical Clock is one of the group of famous 14th- to 16th-century astronomical clocks to be found in the West of England. Others are at Wells, Ottery St Mary, and Wimborne Minster.

The main, lower, dial is the oldest part of the clock, dating from 1484.[3] The fleur-de-lys-tipped hand indicates the hour (and the position of the sun in the sky) on a 24-hour analogue dial. The numbering consists of two sets of Roman numerals I to XII. The silver ball and inner dial shows both the age of the moon and its phase (using a rotating black shield to indicate the moon's phase). The upper dial, added in 1760, shows the minutes.[3]

The Latin phrase Pereunt et imputantur, a favourite motto for clocks and sundials, was written by the Latin poet Martial. It is usually translated as "they perish and are reckoned to our account", referring to the hours that we spend, wisely or not. The original clockwork mechanism, much modified, repaired, and neglected until it was replaced in the early 20th century, can be seen on the floor below. The door below the clock has a round hole near its base. This was cut in the early 17th century to allow entry for the bishop's cat to deter vermin that were attracted to the animal fat used to lubricate the clock mechanism.[3]

Library

Si quis illum inde abstulerit eterne subiaceat maledictioni. Fiat. Fiat.

(If any one removes this he shall be eternally cursed. So be it! So be it!)

The library began during the episcopate of Leofric (1050–1072) who presented the cathedral with 66 books, only one of which remains in the library: this is the Exeter Book (Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501) of Anglo-Saxon poetry.[11] 16 others have survived and are in the British Library, the Bodleian Library or Cambridge University Library. A 10th-century manuscript of Hrabanus Maurus's De Computo and Isidore of Seville's De Natura Rerum may have belonged to Leofric also but the earliest record of it is in an inventory of 1327. The inventory was compiled by the Sub-Dean, William de Braileghe, and 230 titles were listed. Service books were not included and a note at the end mentions many other books in French, English and Latin which were then considered worthless.

In 1412–13 a new lectrinum was fitted out for the books by two carpenters working for 40 weeks. Those books in need of repair were repaired and some were fitted with chains. A catalogue of the cathedral's books made in 1506 shows that the library furnished some 90 years earlier had 11 desks for books and records over 530 titles, of which more than a third are service books.[12]

In 1566 the Dean and Chapter presented to Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury, a manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Gospels which had been given by Leofric;[13] in 1602, 81 manuscripts from the library were presented to Sir Thomas Bodley for the Bodleian Library at Oxford. In 1657 under the Commonwealth the Cathedral was deprived of several of its ancillary buildings, including the reading room of 1412–13. Some books were lost but a large part of them were saved due to the efforts of Dr Robert Vilvaine, who had them transferred to St John's Hospital. At a later date he provided funds to convert the Lady chapel into a library, and the books were brought back.

By 1752 it is thought the collection had grown considerably to some 5,000 volumes, to a large extent by benefactions. In 1761 Charles Lyttelton, Dean of Exeter, describes it as having over 6,000 books and some good manuscripts. He describes the work which has been done to repair and list the contents of the manuscripts. At the same time the muniments and records had been cleaned and moved to a suitable muniment room.[12]

In 1820 the library was moved from the Lady Chapel to the Chapter House. In the later 19th century two large collections were received by the Cathedral, and it was necessary to construct a new building to accommodate the whole library. The collections of Edward Charles Harington and Frederic Charles Cook were together more than twice the size of the existing library, and John Loughborough Pearson was the architect of the new building on the site of the old cloister. During the 20th century the greater part of the library was transferred to rooms in the Bishop's Palace, while the remainder was kept in Pearson's cloister library.[12]

Today, there is a good collection of early medical books, part of which came in 1948 from the Exeter Medical Library (founded 1814), and part on permanent loan from the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital (1,300 volumes, 1965). The most decorated manuscript in the library is a psalter (MS 3508) probably written for the Church of St Helen at Worcester in the early 13th century. The earliest printed book now in the library is represented by only a single leaf: this is Cicero's De officiis (Mainz: Fust and Schoeffer, 1465–66).[12]

Bells

Both of the Cathedral's towers contain bells. The North Tower contains an 80-hundredweight (4.1-tonne) bourdon bell, called Peter. Peter used to swing but it is now only chimed. it also contains two clock bells to sound the quarter hours. The South Tower contains the second heaviest peal of 12 bells hung for change ringing in the world, with a tenor weighing 72 long cwt 2 qr 2 lb (8,122 lb or 3,684 kg).[14] There are also two semitone bells in addition to the peal of 12.[15]

Dean and chapter

As of 7 January 2018:[16]

- Dean — Jonathan Greener (since 26 November 2017 installation)

- Canon Precentor — James Mustard (since 25 March 2018 installation)

- Canon Chancellor — Christopher Palmer (from August 2018 installation)

- Canon Treasurer — Mike Williams (SSM; residentiary canon since November 2016; acting dean, 14 July – 26 November 2017)

- Diocesan Director of Ordinands & Residentiary Canon — Becky Totterdell (canon since April 2017; her predecessor was Canon Pastor and Treasurer)

- Non-Canons[17]

- Acting Precentor — Martin Shaw (honorary assistant bishop; acting since 2017)

- Chaplain — David Gunn-Johnson (retired archdeacon; cathedral chaplain since 2017)

- Curate — Morwenna Ludlow (deaconed 2015, priested September 2016)

Burials

A full listing of monuments and transcription of inscriptions in the Cathedral is contained in: Hewett, John William, Remarks on the Monumental Brasses and Certain Decorative Remains in the Cathedral Church of St Peter, Exeter, to which is Appended a Complete Monumentarium, published in Transactions of the Exeter Diocesan Architectural Society, Volume 3, Exeter, 1846–1849, pp. 90–138 [1]

Persons buried within the Cathedral include the following:

- Leofric (bishop), first Bishop of Exeter (1050–1072)

- Robert Warelwast, Bishop of Exeter (1138–1155)

- Bartholomew Iscanus, Bishop of Exeter (1161–1184)

- John the Chanter, Bishop of Exeter (1186–1191)

- Henry Marshal, Bishop of Exeter (1194–1206)

- Simon of Apulia, Bishop of Exeter (1214–1223)

- Walter Bronescombe, Bishop of Exeter (1258–1280)

- Peter Quinel, Bishop of Exeter (1280–1291)

- Henry de Bracton (c. 1210 – c. 1268), English ecclesiastic and jurist

- Sir Henry de Raleigh (died 1301), knight

- Walter de Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter (1308–1326)

- Sir Richard de Stapledon (died 1326), knight, elder brother of Bishop Stapledon

- James Berkeley (died 1327), Bishop of Exeter

- John Grandisson, Bishop of Exeter (1327–1369)

- Hugh Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (1303–1377) and his wife Margaret de Bohun (died 1391)

- Thomas de Brantingham, English lord treasurer and Bishop of Exeter (1370–1394)

- Sir Peter Courtenay (died 1405), fifth son of Hugh Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon

- Edmund Stafford, Lord Privy Seal, Lord Chancellor, Baron Stafford and Bishop of Exeter (1395–1419)

- Edmund Lacey, Bishop of Exeter (1420–1455), whose tomb had been a shrine, but which was walled over during the Reformation, fragments were uncovered during the Baedeker Blitz[18]

- John Speke (1442–1518) of Whitelackington, Somerset and of Heywood in the parish of Wembworthy and of Bramford Speke, Devon (buried in the Speke Chantry)

- Hugh Oldham, Bishop of Exeter (1504–1519; buried in the Oldham Chantry)

- William Alley, Bishop of Exeter (1560–1571)

- William Bradbridge, Bishop of Exeter (1571–1578)

- John Woolton, Bishop of Exeter (1579–1594)

- Dr. William Cotton, Bishop of Exeter (1598–1621) buried in Exeter Cathedral. His monument with recumbent effigy survives.

- Ofspring Blackall (1655–1716), Bishop of Exeter (1708–1716) buried on the southern side of the choir in an unmarked grave

- John Ross (1719–1792), Bishop of Exeter (1778–1792) buried in the south aisle of the choir, the place being marked by a flat tombstone and the inscription 'J. R., D.D., 1792.'

- Bryan Blundell (1757–1799), Major General in the Army and Lieutenant Colonel of the 45th Regiment of Foot

- Sir Gawen Carew

- Peter (Pierre) of Courtenay (1126–1183), youngest son of Louis VI of France and his second Queen consort Adélaide de Maurienne.

- Sir Peter Carew (c. 1514 – 1575) is not buried in the Cathedral, but is commemorated by a mural monument.

-

Effigies of Hugh Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon, and his wife Margaret de Bohun

-

Rubbing from monumental brass of Sir Peter Courtenay, Exeter Cathedral, south aisle

-

Mural monument to Sir Peter Carew, south transept

-

Wall tablet to Major-General Bryan Blundell Esq, north east chapel

Legends

One 19th century author claimed that an 11th-century missal asserted that King Athelstan, the previous century, had brought together a great collection of holy relics at Exeter Cathedral; sending out emissaries at great expense to the continent to acquire them. Amongst these items were said to be a little of the bush in which the Lord spoke to Moses, and a bit of the candle which the angel of the Lord lit in Christ's tomb.[19]

According to the semi-legendary tale, the Protestant martyr Agnes Prest, during her brief time of liberty in Exeter before her execution in 1557, met a stonemason repairing the statues at the Cathedral. She stated that there was no use repairing their noses, since "within a few days shall all lose their heads".[20] There is a memorial to her and another Protestant martyr, Thomas Benet, in the Livery Dole area of Exeter. The memorial was designed by Harry Hems and raised by public subscription in 1909.[21]

Wildlife

The tube web spider Segestria florentina, notable for its iridescent shiny green fangs, can be found within the outer walls. The walls are made of calcareous stone, which decays from acidic pollution, to form cracks and crevices which the spider and other invertebrates inhabit.[22]

Music

Organists

Recorded names of organists at Exeter go back to Matthew Godwin, 1586. Notable organists at Exeter Cathedral include Victorian composer Samuel Sebastian Wesley, grandson of Methodist founder and hymn-writer Charles Wesley, educator Ernest Bullock, and conductor Thomas Armstrong.

Organ

The Cathedral organ stands on the ornate medieval screen, preserving the old classical distinction between quire and nave. The first organ was built by John Loosemore in 1665. There was a radical rebuild by Henry Willis in 1891, and again by Harrison & Harrison in 1931.[24] The largest pipes, the lower octave of the 32′ Contra Violone, stand just inside the south transept. The organ has one of only three trompette militaire stops in the country (the others are in Liverpool Cathedral and London's St Paul's Cathedral), housed in the minstrels' gallery, along with a chorus of diapason pipes.[23]

In January 2013 an extensive refurbishment began on the organ, undertaken by Harrison & Harrison. The work consisted of an overhaul and a re-design of the internal layout of the soundboards and ranks of the organ pipes.[25] In October 2014 the work was completed and the organ was reassembled, save for the final voicing and tuning of the new instrument.[26]

See also

- Dean of Exeter

- List of cathedrals in the United Kingdom

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- Romanesque architecture

References

- ^ "TimeRef - Medieval and Middle Ages History Timelines - Exeter Cathedral Details". www.timeref.com.

- ^ Erskine et al. (1988) p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e The Cathedral Church of St Peter in Exeter. Printed leaflet distributed at the Cathedral. (2010)

- ^ S C Carpenter (1943) Exeter Cathedral 1942. London: SPCK p. 1-2

- ^ Cothren, Marilyn Stokstad Michael W. (2010). Art History Portable, Book 4 14th-17th Century Art (4th ed., Portable ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0205790941.

- ^ Cothren, Marilyn Stokstad Michael W. (2010). Art History Portable, Book 4 14th–17th Century Art (4th ed., Portable ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 554. ISBN 0205790941.

- ^ "The Exeter Misericords". Exeter Cathedral. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Addleshaw (1921) p. 36

- ^ "Bagpipe Paintings: The Bagpiper of Exeter". prydein.com. Prydein, American Celtic-Rock. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

[photos of the Minstrels Gallery]

- ^ Edmonds (1899). "The Formation and Fortunes of Exeter Cathedral Library". Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association. 106: 36Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Edward Edwards (1901), Memoirs of Libraries, of Museums, and of Archives (2nd ed.), Newport, Isle of Wight, OCLC 3115657

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Lloyd, L. J. (1967) The Library of Exeter Cathedral. Exeter: University of Exeter

- ^ Sayle, Charles (1916). Annals of Cambridge University Library, 1278-1900. Cambridge: University Library. p. 49 (footnote 3).

- ^ "Doves Guide for Bellringers". Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ "Rings of 12". The Rings of 12. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Exeter Cathedral — Chapter Members (Accessed 7 January 2018)

- ^ Exeter Cathedral — Cathedral Clergy (Accessed 7 January 2018)

- ^ www.digitalvirtue.com, Digital Virtue - w:. "404 - Page Not Found". archive.thetablet.co.uk.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Jusserand, J. J. (1891) English Wayfaring Life in the Middle Ages. London: T. Fisher Unwin; p. 327.

- ^ John Foxe (1887 republication), Book of Martyrs, Frederick Warne and Co, London and New York, pp. 242–44

- ^ Cornforth, David. "Livery Dole Martyr's Memorial". Exeter Memories. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ Wild Devon The Magazine of the Devon Wildlife Trust, pages 4 to 7 Winter 2009 edition

- ^ a b "The National Pipe Organ Register - NPOR". www.npor.org.uk.

- ^ "Exeter Cathedral". Harrison-organs.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Organ Restoration Begins". Exeter Cathedral Website. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Cathedral organs". Exeter Cathedral website.

Sources

- Addleshaw, Percy (1921). Bell's Cathedrals: The Cathedral Church of Exeter (New and revised ed.). G. Bell & Sons, London. Online copy

- here at Project Gutenberg

- Erskine, Audrey; Hope, Vyvyan; Lloyd, John (1988). Exeter Cathedral - A Short History and Description. Dean and Chapter of Exeter Cathedral. ISBN 0-9503320-4-6.

Further reading

- Henry, Avril K.; Hulbert, Anna C. "Exeter Cathedral Keystones & Carvings: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Sculptures & Their Polychromy". Universities of Essex – History Data Service. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- Barlow, Frank, et al. (1972) Leofric of Exeter: essays in commemoration of the foundation of Exeter Cathedral Library in A.D. 1072; by Frank Barlow, Kathleen M. Dexter, Audrey M. Erskine, L. J. Lloyd. Exeter: University of Exeter

- Orme, Nicholas (2009) Exeter Cathedral: the first thousand years, 400-1550. Exeter: Impress ISBN 0-9556239-8-7 (a history of the successive churches on the site from Roman to early Tudor times)

External links

- Anglican cathedrals in England

- Benedictine monasteries in England

- Former Roman Catholic churches in England

- Pre-Reformation Roman Catholic cathedrals

- Churches in Exeter

- Church of England church buildings in Devon

- Diocese of Exeter

- History of Exeter

- Monasteries in Devon

- Tourist attractions in Exeter

- Grade I listed cathedrals

- Grade I listed churches in Devon

- Norman architecture in England

- English Gothic architecture in Devon

- Exeter Cathedral

- Grade I listed monasteries

- British churches bombed by the Luftwaffe