Mastaba of Kaninisut

The Mastaba of Kaninisut (or Ka-ni-nisut [Ka-nj-nswt]), or Mastaba G 2155, is an ancient Egyptian mastaba tomb, located at Giza in the West field of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The cult chamber of the mastaba is now on display in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna with inventory number 8006. Kaninisut was a high state official in the Fourth dynasty or early Fifth dynasty in the Old Kingdom (c. 2500 BC), as demonstrated by the location and size of his tomb and his numerous honorific titles. The cult chamber of Kaninisut was built of the best quality white Tura limestone and decorated with fine, raised reliefs, which mainly depict offerings, scenes of funerary ritual and Kaninisut with his family. Kaninisut's descendants built additional smaller tombs within the large mastaba.

Location

The Mastaba of Kaninisut lies in the Giza West Field, the western cemetery of Giza. There are clearly planned fields of mastabas to the east and west of the Great Pyramid. The closest relatives of Khufu, the owner of the Great Pyramid, were buried in the East Field and high officials and dignitaries were buried in the West Field. Through this privilege, the deceased could be included in the conceptual world of the royal afterlife and receive the necessary offerings via the funerary cult operated from the royal mortuary temple. Construction, alignment and decoration of the individual private tombs reflected the contemporary cultural hierarchy. During Khufu's reign a total of 77 tombs were built in the two grave fields and numerous graves were added in later times. The regular arrangement of the individual mastabas indicates that they were constructed altogether. Apparently the completed mastabas were handed over undecorated to their owners, who were responsible for any further decoration.[1] The mastaba of Kaninisut is located in the westernmost part of its section of the cemetery, which is referred to as a cemetery "en échelon" on account of the arrangement of its tombs.[2]

Discovery and sale of the cult chamber

In 1902, the Giza West Field was divided into three parallel sections for each of the nations which had been granted an excavation concession - from east to west, the United States, the Kingdom of Italy and the German Empire. Between 1903 and 1907 Georg Steindorff undertook three excavation campaigns. In 1911, Steindorff and Hermann Junker, who had previously excavated in Nubia, decided to swap their concessions. Thus, the Austrian Academy of Sciences took over the German concession at Giza.[3]

On 10 January 1913, Hermann Junker and his colleagues discovered the Mastaba of Kaninisut. Shortly thereafter it was decided that that cult chamber would be sold to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, so that it could be displayed there as a typical example of Old Kingdom funerary architecture. Hermann Junker remarked that "The entire chamber is in every respect so beautiful and instructive that I consider it pre-eminently suitable for being transferred to Vienna."[4]

The Viennese industrialist Rudolf Maass covered the costs of the sale and transfer - around 30,000 krone. On 27 January 1914, the k.u.k. Oberstkämmerer and the Egyptian antiquities service signed off on the sale. The cult chamber was removed over the course of a month and was transported to Vienna in 32 crates with a total weight of 65 tonnes. They began to arrive at Vienna in July 1914.[3]

Due to the First World War and the poor economic situation after the war, the reconstruction of the cult chamber did not occur for more than ten years. The rebuilt cult chamber was first made accessible to the public on 17 June 1925.[3]

Kaninisut and his family

Kaninisut was a high official during the fourth or early fifth dynasties, as is shown by the location and size of his tomb at Giza and by his numerous honorific titles. The exact reign in which he lived is not currently clear. His family may have continued into the fifth generation, since his descendants had their graves built in the immediate proximity of his mastaba. From the tomb architecture and titles of his descendants, however, the social decline of his family can be discerned. Apparently, his family increasingly lost the high position he had enjoyed in the royal court.[5]

Kaninisut bore titles such as "Lord of the kilt," "Sole Friend" and "Beloved son of the king," which were originally only used by relatives of the king, but came to be honorific titles for very important non-royals over the course of the Old Kingdom. They do not indicate much about Kaninisut's actual role. Most of the time in his titularies, the title of Sem priest is in first position. This indicates a significant role in divine and funerary cult.[5]

Kaninisut's wife and two sons are also depicted in the cult chamber.[5]

Description and function of the mastaba

The tomb of Kaninisut was a mastaba tomb. The term "mastaba", which is Arabic for bench, derives from the appearance of these tombs: the upper building is rectangular with slightly inclined side walls and thus looks like an oversized bench. The core structure of Kaninisut's mastaba is 24 m long by 10.2 m wide, the height can no longer be determined due to its destruction. The outer walls were made of limestone blocks clad with a layer of fine white Tura limestone. There are no rooms in the interior of the upper building; it is filled in with rubble. Towards the end of the reign of Khufu it was becoming increasingly common to place the cult rooms within the upper building, before this they were added to the east facade of the tomb. Apparently in the case of Kaninisut's mastaba, the basic structure of the tomb was completed towards the end of Khufu's reign, but it required numerous adaptations in order to fit the new building style. Rather than to hollow out the mastaba, it was apparently decided to extend the tomb to the south, in order to install the cult chamber there.[2]

A mudbrick porch was erected on the east facade in front of the entrance to the cult chamber. A 2.55 m long and 0.75 - 1.05 m wide passageway led to the cult chamber, which was sealed with a wooden door. The 3.60 m long, 1.45 m wide and 3.16 m high chamber contained two false doors in the west wall, which offerings were placed in front of. Behind the false door was the serdab, a small room which was completely walled off, in which the ka-statue of the tomb's owner was located. However, Hermann Junker was not able to locate the ka-statue of Kaninisut. The chamber was robbed in ancient times, leaving traces of forceful entry.[2]

The substructure of Kaninisut's mastaba was a 17 m deep vertical shaft grave, which led, via a short corridor, to a grave chamber roughly hewn from the rock. The rough execution of the grave chamber stands in sharp contrast to the fine execution of the cult chamber. Apparently, the underground spaces' execution was increasingly neglected in the later fourth dynasty. No remains of the deceased could be found.[6]

On the east side of the mastaba, the son of Kaninisut, who was also called Kaninisut, had a modest tomb for himself added to his father's mastaba. The upper building is 8.8 m long and 3.5 m wide. Through the east side of this addition, one could access its cult chamber, which also had two false doors in the west wall. The underground chamber for the sarcophagus was found largely empty and was probably robbed in ancient times. Despite this, some grave goods were found lying around, including fine alabaster vessels, small copper tools and four clay jars which had held the organs of the mummy.[6]

A further addition is located on the north side of the main mastaba of Kaninisut. This tomb belngs to another Kaninisut, probably the grandson of the owner of the main tomb. Not much now remains of this tomb.[6]

In the immediate proximity of the mastaba, Iri-en-re and Ankh-ma-re, probably the great-grandson and great-great-grandson of Kaninisut also erected their tombs. The small street between the Mastaba of Nisut-nefer (G 4970) and Mastaba G 4980 was perhaps the only practical space available for their tombs. The tomb of Iri-en-re was built at the northwest corner of the mastaba of Nisut-nefer and that of Ankh-ma-re was built further to the east.[6]

Relief decoration of the cult chamber

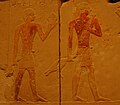

The cult chamber of Kaninisut is made of the best white Tura limestone and decorated with fine raised reliefs, which are now displayed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Some remains of the original paintwork still survive. Typically for Egyptian art, people are depicted in a combination of frontal and side views. Thus, eyes, shoulders, and chests are shown in frontal view while heads, arms, and legs appear in side view.

Entrance corridor

On the northern and southern walls of the entrance corridor are dining scenes. In each of them, Kaninisut sits at an offering table with twelve loaves of bread stacked close together on it, symbolising his food supply in the afterlife. Kaninisut wears a leopard pelt, the symbol of the sem priest. On the south wall it is a long pelt and on the northern wall a more rarely depicted short pelt.[7]

To the right of the dining scene on the northern wall, there are four priests, who are depicted on a smaller scale than Kaninisut, carrying out ritual offerings for the dead: the first one is labelled as the "cupbearer of the great, full table" and is kneeling with a vessel and a loaf of bread in his hands. Behind him, an Ut-priest carries out the offering ritual, extending the fist of his right hand and touching his forehead with his left hand. The third priest holds up a washing bowl, which was used for cleaning cult places. Behind him stands a Heri-wedjeb-priest with his hand raised in a speaking gesture. He takes the gifts involved in the offering ritual: incense, anointing oil, green eyeshadow, black eyeshadow, wine, wˁḥ-fruit, weh-fruit, buckthorn bread, figs, four loaves of dpt bread, buckthorn bread, t3-rtḥ bread, roasted wheat, white and green zẖt barley. On the southern wall, another man is depicted behind the Heri-wedjeb-priest, holding a large cow's leg.[7]

South wall at the door jamb

At the south door jamb, the delivery of an antelope is depicted on the south wall. Two men, wearing only kilts with three bands, bring the animal as an offering. The funerary priest Ankh-haf holds the antelope at the mouth and horns. The "leader of the hall" drives the animal forward with a stick. A man in front brings other offerings. The antelope is a donation from a property which provided materials for the funerary cult of Kaninisut. Above it are further images of offering gifts, arranged in two rows.[8]

East wall

On the east wall above the entrance are two ship scenes. The upper scene depicts a sail boat, the lower a row boat. A long narrow band underneath the boats symbolises the water and simultaneously forms the dividing line between the two scenes. Kaninisut is depicted standing at the middle of each boat, with a stick for support. The ship scenes depict the journeys of the deceased in the afterlife to the old capitals of Buto and Heliopolis.[9]

The two upper registers of the rest of the east wall depict personifications of the properties which provided offerings. Arm and hand postures are similar for all figures: with the right hand they hold a basket with offering gifts on their head, from their left hand an animal hangs down. The figures represent the properties which provided regular funerary offerings.[9]

In the third register, the delivery and slaughter of cattle is shown. In the left half, two long horned cattle and a calf are brought forward, in the right half two cattle are slaughtered.[9]

In the lowest register, thirteen men bring small tables or plates with bread, fruit and pieces of meat.[9]

-

East wall, ship scenes above the door

-

East wall, delivery scenes

South wall

The small south wall contains a list of offerings and a dining scene. The offering list consists of eight registers, in which the captions are arranged from left to right in short vertical columns without dividing lines. The dining scene is at the right hand side of the lower four registers. In the ritual offering lists, the offerings and ritual actions are noted, which were carried out in the regular funerary cult at the tomb. They begin with the list of the entrance rites, which were carried out by the funerary priest, like the purification of the cult space by sweeping and pouring water, washing hands, burning incense and supply of the seven holy oils and anointments. After this follows the list of foods and drinks which were to be brought in a defined order. These consist of various kinds of breads, cakes, meats, poultry, fruit and vegetables. Only fragments of the dining scene survive.[10]

West wall

The west wall was the chief cultic focus of the tomb and contained two false doors. The south false door consists of an outer frame, a false door table, an inner frame, a wind screen and a door niche. On the crossbeam of the outer frame is the offering formula: "The offering which the give gives, which Anubis who stands at the top of the divine hall gives; may he be buried in the west: the lord who is worthy to the great god, after he has reached very great age, the Sem-Priest and leader of the skirts Kaninisut." A podium stands in front, on which the ritual equipment and offerings could be placed. Behind the door was the serdap with the ka statue (no longer extant).[11]

On the left outer doorpost, two men are depicted one above the other, bringing writing equipment or fabric strips. On the left inner doorpost, are other servants who hold various things in their hands, including a pot, a scrll, and a sack. In the rectangular false door table is another dining scene with a short offering list. Above this, some titles of Kaninisut are listed. A somewhat different list of titles appears on the wind screen between the two doorposts.[11]

An additional architrave is located between the two false door architraves, which contains a full list of all Kaninisut's titles: The Sem-Priest, the lord of the kilt, the friend, the Sema-Priest of Horus, the Administrator of Dep, Mouth to the people of Pe, the sole friend, the Guardian of the Mystery of the Morning house, the Chief of El Kab, the Chief of Allocations of the House of Life, the Leader of the Petitions, the Leader of the Black Jar, the Prophet of the Lord of Buto the Son of the Black Jar, the Propher of the Lord of Buto the son of the Northern one, the Lector Priest, the one in the Entourage of the Ha, the only one among the great people of the feast: Kaninisut.[11]

Under this Kaninisut is depicted with his wife Neferhanisut and their children. The faces of the children and of Kaninisut have been intentionally destroyed. To the left of the family, the numerous servants of Kaninisut's household are depicted, including four scribes. A container stands amongst them with papyrus documents and bound papyrus scrolls. Underneath are five priests, who carry ritual equipment and offerings. More people bringing offerings can be seen in the lowest register of this space between the false doors.[11]

The northern false door of the west wall is an additional ritual location. It also features a short offering list, names and titles of Kaninisut and an offering scene. On the inner doorposts, there are further servants carrying Hes vases. Another servant in the lower part of the outer doorposts holds up a washstand. All the servants face towards the door niche. In the door niche, there is a large hole which was possibly cut by a grave robber hoping to find a serdab with a ka-statue in it. In the upper portion of the doorposts, the wife of Kaninisut is depicted, who does not look towards the door niche like the servants, but instead towards the large image of Kaninisut on the north wall.[11]

-

Northern false door of the west wall

-

Detail of the northern false door: dining scene

-

Detail of the west wall: Kaninisut and his wife Neferhanisut

-

Detail of the west wall: Offering-bringer

North wall

A large image of Kaninisut dominates the north wall. Above it is a horizontal inscription with a detailed list of his titles. Kaninisut stands with his left leg striding forward. In his lef hand he holds a long staff, in his right hand a Sekhem scepter. His hair is in fairly long locks. He wears a short kilt and a leopard pelt, which is held in place by a fabric strip across his chest. Behind him stands his oldest son, Her-wer, who is shown at a much smaller scale; he only reaches halfway up his father's calf. He is depicted as a naked child with a sidelock of youth, a typical presentation of the children of tombowners, even when the children were actually adults.

In front of Kaninisut are three rows depicting scribes and officials of his household. Right at the front in the top register is his chief steward, Wehem-ka, who presents a papyrus document.[12]

References

- ^ Michael Haase: Eine Stätte für die Ewigkeit. Der Pyramidenkomplex des Cheops aus baulicher, architektonischer und kulturhistorischer Sicht. von Zabern, Mainz 2004, pp. 71ff.

- ^ a b c Hölzl: Die Kultkammer des Ka-ni-nisut im Kunsthistorischen Museum Wien. 2005, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Hölzl, 2005, pp. 9ff. and 31.

- ^ "Die ganze Kammer ist in jeder Beziehung so schön und lehrreich, dass ich sie in erster Linie für geeignet halte, nach Wien übertragen zu werden."

- ^ a b c Hölzl. 2005, pp. 25ff.

- ^ a b c d Hölzl. 2005, pp. 31ff.

- ^ a b Hölzl. 2005, pp. 43–45; Hözl: Reliefs und Inschriftensteine des Alten Reiches II. 2001, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Hölzl. 2005, p. 45; Hözl. 2001, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b c d Hölzl. 2005, pp. 45–48; Hözl. 2001, pp. 36–43.

- ^ Hölzl. 2005, pp. 48–49; Hözl. 2001, pp. 43–46.

- ^ a b c d e Hölzl. 2005, pp. 49–53; Hözl. 2001, pp. 46–51.

- ^ Hölzl. 2005, pp. 53–55; Hözl. 2001, pp. 51–53.

External links

- KHM: Kultkammer das Ka-ni-nisut

- Rudolf Koch: Die Kultkammer des Kaninisut

- Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae: Mastaba des Kai-ni-nisut Transkription und Übersetzung der Inschriften

Bibliography

- Jürgen Brinks. "Die Entwicklung der Mastaba bis zum Ende des Alten Reiches." In: Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. (SAK) Vol. 2, Hamburg 1989, pp. 35–44.

- Regina Hölzl. Die Kultkammer des Ka-ni-nisut im Kunsthistorischen Museum Wien. 1st Edition. Brandstätter, Wien 2005, ISBN 978-3-85498-436-8 (online; PDF; 35,1 MB)

- Regina Hölzl. Reliefs und Inschriftensteine des Alten Reiches II (= Corpus Antiquitatum Aegyptiacarum. (CAA) Lfg. 21. Ed.: Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien. Lose-Blatt-Katalog Ägyptischer Altertümer in Mappe). von Zabern, Mainz 2001 (online; PDF; 89,5 MB)

- Peter Jánosi. Österreich vor den Pyramiden. Die Grabungen Hermann Junkers im Auftrag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien bei den grossen Pyramiden in Giza. Wien 1997. (online; PDF; 87,7 MB)

- Hermann Junker. Giza II. Bericht über die von der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien auf gemeinsame Kosten mit Dr. Wilhelm Pelizaeus unternommenen Grabungen auf dem Friedhof des Alten Reiches bei den Pyramiden von Giza. Band II: Die Mastabas der beginnenden V.Dynastie auf dem Westfriedhof. Wien, Leipzig 1934. (online; PDF; 43,6 MB)

- Hermann Junker. Die Kultkammer des Prinzen Kanjnjswt im Wiener Kunsthistorischen Museum. Wien 1955. (Englische Ausgabe online; PDF; 3,7 MB)