Sydney Airport

Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Leased Commonwealth Airport | ||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Sydney Airport Corporation Limited | ||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Sydney | ||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Mascot, New South Wales, Australia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 21 ft / 6 m | ||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 33°56′46″S 151°10′38″E / 33.94611°S 151.17722°E | ||||||||||||||||||

| Website | sydneyairport.com.au | ||||||||||||||||||

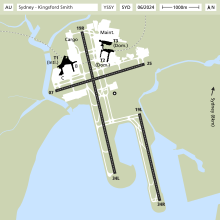

| Map | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Source: AIP[5] Passenger and aircraft movements from the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics[2] | |||||||||||||||||||

Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport[6] (colloquially Mascot Airport, Kingsford Smith Airport, or Sydney Airport; IATA: SYD, ICAO: YSSY; ASX: SYD) is an international airport in Sydney, Australia located 8 km (5 mi) south of Sydney city centre, in the suburb of Mascot. The airport is owned by the ASX-listed Sydney Airport Group. It is the primary airport serving Sydney, and is a primary hub for Qantas, as well as a secondary hub for Virgin Australia and Jetstar Airways. Situated next to Botany Bay, the airport has three runways, colloquially known as the east–west, north–south and third runways.

Sydney Airport is one of the world's longest continuously operated commercial airports[7] and the busiest airport in Australia, handling 42.6 million passengers[8] and 348,904 aircraft movements[9] in 2016–17. It was the 38th busiest airport in the world in 2016. Currently 46 domestic and 43 international destinations are served to Sydney directly.

In 2018, the airport was rated in the top 5 worldwide for airports handling 40–50 million passengers annually and was overall voted the 20th best airport in the world at the Skytrax World Airport Awards.[10]

The airport's Air Traffic Control Tower is listed on the Commonwealth Heritage List.[11]

History

1919–1930: Early history

The land used for the airport had been a bullock paddock.[12] Nigel Love, who had been a pilot in the First World War, was interested in establishing the nation's first aircraft manufacturing company. This idea would require him to establish a factory and an aerodrome close to the city. A real estate office in Sydney told him of some land owned by the Kensington Race Club that was being kept as a hedge against its losing its government-owned site at Randwick. It had been used by a local abattoir which was closing down, to graze sheep and cattle. [citation needed] This land appealed to Love as the surface was perfectly flat and was covered with a pasture of buffalo grass. The grass had been grazed so evenly by the sheep and cattle that it required little to make it serviceable for aircraft. [citation needed] In addition, the approaches on all four sides had no obstructions, it was bounded by a racecourse, gardens, a river and Botany Bay.

Love established Mascot as a private concern, leasing 80 hectares (200 acres) from the Kensington Race Club for three years. It initially had a small canvas structure but was later equipped with an imported Richards hangar. The first flight from Mascot was on November 1919 when Love carried freelance movie photographer Billy Marshall up in an Avro. The official opening flight took place on 9 January 1920, also performed by Love.[13]

In 1921, the Commonwealth Government purchased 65 hectares (161 acres) in Mascot for the purpose of creating a public airfield. In 1923, when Love's three-year lease expired, the Mascot land was compulsorily acquired by the Commonwealth Government from the racing club.[12] The first regular flights began in 1924.

1930–1960

In 1933 the first gravel runways were built. By 1949 the airport had three runways – the 1,085-metre (3,560 ft) 11/29, the 1,190-metre (3,904 ft) 16/34 and the 1,787-metre (5,863 ft) 04/22. The Sydenham to Botany railway line crossed the latter runway approximately 150 metres (490 ft) from the northern end and was protected by special safeworking facilities.[14] The Cooks River was diverted away from the area in 1947–52 to provide more land for the airport and other small streams were filled. When Mascot was declared an aerodrome in 1920 it was known as Sydney Airport. On 14 August 1936 the airport was renamed Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport[15] in honour of pioneering Australian aviator Sir Charles Kingsford Smith. Up to the early 1960s the majority of Sydney-siders referred to the airport as Mascot. The first paved runway was 07/25 and the next one constructed was 16/34 (now 16R/34L), extended into Botany Bay, starting in 1959, to accommodate jet aircraft.[citation needed] Runway 07/25 is used mainly by lighter aircraft, but is used by all aircraft including Airbus A380s when conditions require. Runway 16R/34L is presently the longest operational runway in Australia, with a paved length of 4,400 m (14,300 ft) and 3,920 m (12,850 ft) between the zebra thresholds.

Modern history

By the 1960s, the need for a new international terminal had become apparent, and work commenced in late 1966. Much of the new terminal was designed by Paynter and Dixon Industries.[16] The plans for the design are held by the State Library of New South Wales.[17]

The new terminal was officially opened on 3 May 1970, by HM Queen Elizabeth II. The first Boeing 747 "Jumbo Jet" at the airport, Pan American's Clipper Flying Cloud (N734PA), arrived on 4 October 1970. The east-west runway was then 2,500 m (8,300 ft) long;[18] in the 1970s the north-south runway was expanded to become one of the longest runways in the southern hemisphere. The international terminal was expanded in 1992 [citation needed] and has undergone several refurbishments since then, including one that was completed in early 2000 in order to re-invent the airport in time for the 2000 Olympic Games held in Sydney. The airport additionally underwent another project development that began in 2010 to extend the transit zone which brought new duty free facilities, shops & leisure areas for passengers. [citation needed]

The limitations of having only two runways that crossed each other had become apparent and governments grappled with Sydney's airport capacity for decades; eventually the controversial decision to build a third runway was made. The third runway was parallel to the existing runway 16/34, entirely on reclaimed land from Botany Bay. A proposed new airport on the outskirts of Sydney was shelved in 2004, before being re-examined in 2009–2012 showing that Kingsford Smith airport will not be able to cope by 2030.

Curfew

The "third runway", which the Commonwealth government commenced development of in 1989 and completed in 1994, remained controversial because of increased aircraft movements, especially over many inner suburbs. In 1995 the Common Cause - No Aircraft Noise party (also known as the No Aircraft Noise Party) was formed to contest the state seat of Marrickville. The results of the election that year show that the party did not win a seat in parliament, but came close.[19] The party does not appear to have entered candidates for any subsequent election.

In 1995, the Australian Parliament passed the Sydney Airport Curfew Act 1995, which limits the operating hours of the airport. This was done in an effort to curb complaints about aircraft noise. The curfew prevents aircraft from taking off or landing between the hours of 11 pm and 6 am. A limited number of scheduled and approved take-offs and landings are permitted respectively in the "shoulder periods" of 11 pm to midnight and 5 am to 6 am. The Act does not stop all aircraft movements overnight, but limits movements by restricting the types of aircraft that can operate, the runways they can use and the number of flights allowed.[20] During extreme weather, flights are often delayed and it is often the case that people on late flights are unable to travel on a given day. As of 2009[update], fines for violating curfew have been levied against four airlines, with a maximum fine of A$550,000 applicable.[21]

In addition to the curfew, Sydney Airport also has a cap of 80 aircraft movements per hour which cannot be exceeded, leading to increased delays during peak hours.[22]

Expansion

In 2002, the Commonwealth Government sold Sydney Airports Corporation Limited (later renamed Sydney Airport Corporation Limited, SACL), the management authority for the airport, to Southern Cross Airports Corporation Holdings Ltd. 82.93 per cent of SACL is owned by MAp Airports International Limited, a subsidiary of Macquarie Bank, Sydney Airport Intervest GmbH own 12.11 per cent and Ontario Teachers' Australia Trust own 4.96 per cent.[23] SACL holds a 99-year lease on the airport which remains Crown land and as such is categorised as a Leased Federal Airport.[24]

Since the international terminal's original completion, it has undergone two large expansions. One such expansion is underway and will stretch over twenty years (2005–25). This will include an additional high-rise office block, the construction of a multi-level car park, the expansion of both international and domestic terminals. These expansions—and other plans and policies by Macquarie Bank for airport operations—are seen as controversial, as they are performed without the legal oversight of local councils, which usually act as the local planning authority for such developments. As of April 2006[update], some of the proposed development has been scaled back.[25]

Sydney Airport's International terminal underwent a $500 million renovation that was completed in mid-2010. The upgrade includes a new baggage system, an extra 7,300 m2 (78,577 sq ft) of space for shops and passenger waiting areas and other improvements.[26]

In March 2010, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission released a report sharply critical of price gouging at Sydney airport, ranking it fifth out of five airports. The report noted Sydney Airport recorded the highest average prices at $13.63 per passenger, compared to the lowest of $7.96 at Melbourne Airport, while the price of short-term parking had almost doubled in the 2008–09 financial year, from $28 to $50 for four hours. The report also accused the airport of abusing its monopoly power.[27]

Future

In December 2011, Sydney Airport announced a proposal to divide the airport into two airline-alliance-based precincts; integrating international, domestic and regional services under the one roof by 2019. The current domestic Terminal 2 and Terminal 3 would be used by Qantas, Jetstar and members of the oneworld airline alliance while today's international Terminal 1 would be used by Virgin Australia and its international partners. Other international airlines would continue to operate from T1.[28]

In September 2012, Sydney Airport and MD CEO Kerrie Mather announced the airport had abandoned the proposal to create alliance-based terminals in favour of terminals "based around specific airline requirements and (passenger) transfer flows". She stated the plan was to minimise the number of passengers transferring between terminals.[29] In June 2013 the airport released a draft version of its 2013 Masterplan, which proposes operating domestic and international flights from the same terminals using 'swing gates', along with upgrading Terminal 3 (currently the Qantas domestic terminal) to accommodate the Airbus A380.[30][31]

On 17 February 2014, the Australian Government approved Sydney Airport's Master Plan 2033,[32] which outlines the airport's plans to cater for forecast demand of 74 million passengers in 2033. The plan includes Sydney Airport's first ever integrated ground transport plan.[33]

Terminals

Sydney Airport has three passenger terminals. The International Terminal is separated from the other two by a runway; therefore, connecting passengers need to allow for longer transfer times.

Terminal 1

Terminal 1 was opened on 3 May 1970, replacing the old Overseas Passenger Terminal (which was located where Terminal 3 stands now) and has been greatly expanded since then. Today it is known as the International Terminal, located in the airport's north western sector. It has 25 gates (thirteen in concourse B numbered 8–37, and twelve in concourse C numbered 50–63) served by aerobridges. Pier B is used by Qantas, all Oneworld members and all Skyteam members (except Delta). Pier C is used by Virgin Australia and its partners (including Delta) as well as all Star Alliance members. There are also a number of remote bays which are heavily utilised during peak periods and for parking of idle aircraft during the day.

The terminal building is split into three levels, one each for arrivals, departures and airline offices. The departure level has 20 rows of check-in desks each with 10 single desks making a total of 200 check-in desks. The terminal hosts eight airline lounges: two for Qantas, and one each for Etihad Airways, Air New Zealand, Singapore Airlines, Emirates, American Express and SkyTeam. The terminal underwent a major $500 million redevelopment that was completed in 2010, by which the shopping complex was expanded, outbound customs operations were centralised and the floor space of the terminal increased to 254,000 square metres (2,730,000 sq ft).[34] Further renovations began in 2015 with a reconfiguration and decluttering of outbound and inbound duty-free areas, extension of the airside dining areas and installation of Australian Border Force outbound immigration SmartGates. These works were completed in 2016.[35]

Terminal 2

Terminal 2, located in the airport's north-eastern section, was the former home of Ansett Australia's domestic operations. It features 16 parking bays served by aerobridges and several remote bays for regional aircraft. It serves FlyPelican, Jetstar, Regional Express Airlines, Tigerair Australia, Virgin Australia and Virgin Australia Regional Airlines. There are lounges for Regional Express Airlines and Virgin Australia.[citation needed]

Terminal 3

Terminal 3 is a domestic terminal, serving Qantas with QantasLink flights having moved their operations from Terminal 2 to Terminal 3 on 16 August 2013.[36][37] Originally, it was home for Trans Australia Airlines (later named Australian Airlines). Like Terminal 2 it is located in the north-eastern section.

The current terminal building is largely the result of extensions designed by Hassell that were completed in 1999. This included construction of a 60-metre roof span above a new column-free checkin hall and resulted in extending the terminal footprint to 80,000 square metres.[38] There are 14 parking bays served by aerobridges, including two served by dual aerobridges. Terminal 3 features a large Qantas Club lounge, along with a dedicated Business Class and Chairmans lounge. Terminal 3 also has a 'Heritage Collection' located adjacent to gate 13, dedicated to Qantas and including many collections from the airline's 90-plus years of service. It also has a view of the airport's apron and is used commonly by plane-spotters.

Qantas sold its lease of Terminal 3, which was due to continue until 2019, back to Sydney Airport for $535 million. This means Sydney Airport resumes operational responsibility of the terminal, including the lucrative retail areas.[39]

Freight Terminals

The airport is a major hub for freight transport to and from Australia handling approx. 45 percent of the national cargo traffic. Therefore it is equipped with extensive freight facilities including seven dedicated cargo terminals operated by several handlers.[40]

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

- Notes

^a The Qantas flight QF11 from Sydney to New York operates with a stop in Los Angeles, where all passengers disembark and clear US customs while the flight continues to New York carrying all connecting passengers from Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne. Although the same flight number continues to New York there is an aircraft swap at Los Angeles from an A380 to 787. So an entry for a direct New York flight is not included (the 787 arrives from Brisbane). Furthermore, it is not possible to fly solely between LAX and JFK as the US government does not allow foreign airlines from serving domestic flights in the US.

Cargo

Second Sydney airport

The local, state and federal governments have investigated the viability of building a second major airport in Sydney since the 1940s.[66] Significant passenger growth at Sydney Airport indicates the potential need for a second airport — for example, total passenger numbers increased from less than 10 million in 1985–86 to over 25 million in 2000–01, and over 40 million in 2015–16.[8] This growth is expected to continue, with Sydney region passenger demand forecast to reach 87 million passengers by 2035.[67]

On 15 April 2014, the Federal Government announced that Badgerys Creek would be Sydney's second international airport, to be known as Western Sydney Airport.[68] Press releases suggest that the airport will not be subject to curfews and will open in phases, initially with a single airport runway and terminal.[69] It would be linked to Sydney Airport by local roads and motorways, and by extensions to the existing suburban rail network.[70] In May 2017 the Federal Government announced it would build (pay for) the second Sydney Airport, after the Sydney Airport Group declined the Government's offer to build the second airport.[71]

Traffic statistics

Domestic

Sydney Airport handled over 27 million domestic passengers in 2017.[8]

| Rank | Airport | Passengers handled | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9,250,822 | ||

| 2 | 4,788,059 | ||

| 3 | 2,751,593 | ||

| 4 | 1,908,584 | ||

| 5 | 1,719,947 | ||

| 6 | 1,135,079 | ||

| 7 | 951,976 | ||

| 8 | 686,243 | ||

| 9 | 612,458 | ||

| 10 | 424,912 | ||

| 11 | 346,515 | ||

| 12 | 318,073 | ||

| 13 | 283,397 | ||

| 14 | 221,836 | ||

| 15 | 199,958 |

International

Sydney Airport handled 15.6 million international passengers in 2016–17.[8]

| Rank | Airport | Passengers handled | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,556,816 | ||

| 2 | 1,520,882 | ||

| 3 | 1,149,236 | ||

| 4 | 859,610 | ||

| 5 | 819,223 | ||

| 6 | 660,946 | ||

| 7 | 620,876 | ||

| 8 | 587,157 | ||

| 9 | 534,089 | ||

| 10 | 495,485 | ||

| 11 | 487,149 | ||

| 12 | 485,291 | ||

| 13 | 474,013 | ||

| 14 | 458,922 | ||

| 15 | 451,373 |

Notes

Tokyo includes services to both Haneda and Narita airports.

Freight

In 2016–17 Sydney Airport handled 489,183 tonnes of international air freight and 23,349 tonnes of international air mail.[8]

Access

The airport is accessible via the Airport Link underground rail line. The International Airport railway station is located below the International terminal, while the Domestic Airport railway station is located under the car park between the domestic terminals (Terminal 2 and Terminal 3). While the stations are part of the Sydney Trains suburban network, they are privately owned and operated by the Airport Link consortium and their use is subject to a surcharge.[74][75] The trains that service the airport are regular suburban trains. Unlike airport trains at some other airports, these do not have special provisions for customers with luggage, do not operate express to the airport and may have all seats occupied by commuters before the trains arrive at the airport.

State Transit operates route 400 from the airport to Bondi Junction railway station stopping at both the International and Domestic terminals and Mascot railway station. This route connects to the eastern suburbs[76] while Transit Systems Sydney operates route 420 from Westfield Eastgardens to Burwood via both International and Domestic terminals, as well as Banksia and Rockdale railway stations.[77]

Sydney Airport has road connections in all directions. Southern Cross Drive (M1), a motorway, is the fastest link with the city centre. The M5 South Western Motorway (including the M5 East Freeway) links the airport with the south-western suburbs of Sydney. A ring road runs around the airport consisting of Airport Drive, Qantas Drive, General Holmes Drive, M5 East Freeway and Marsh Street. General Holmes Drive features a tunnel under the main north-south runway and three taxiways as well as providing access to an aircraft viewing area. Inside the airport a part-ring road – Ross Smith Avenue (named after Ross MacPherson Smith) – connects the Domestic Terminal with the control tower, the general aviation area, car-rental company storage yards, long-term car park, heliport, various retail operations and a hotel. A perimeter road runs inside the secured area for authorised vehicles only.

The Airport runs several official car parks—Domestic Short Term, Domestic Remote Long Term, and International Short/Long Term.[78]

The International Terminal is located beside a wide pedestrian and bicycle path. It links Mascot and Sydney City in the north-east with Tempe (via a foot bridge over Alexandra Canal) and Botany Bay to the south-west. All terminals offer bicycle racks and are also easily accessible by foot from nearby areas.

Accidents and incidents

- On 19 July 1945 a Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF) bound for Manus Island failed to gain altitude after taking off from Sydney's now non-existent runway 22, struck trees and crashed into Muddy Creek, north of Brighton-Le-Sands.[79][80] The aircraft exploded on impact,killing all 12 passengers and crew on board. All the victims were service personnel, five from the RAF, one from the Royal New Zealand Air Force and six from the Royal Navy.[81]

- On 18 June 1950 a Douglas DC-3 of Ansett Airways taxiing for take-off from runway 22 for a night-time passenger flight to Brisbane, hit and partially derailed a coal train travelling on the railway line that crossed the runway. Only the co-pilot was injured.[82]

- On 30 November 1961, Ansett-ANA Flight 325, a Vickers Viscount, crashed into Botany Bay shortly after take-off. The starboard (right) wing failed after the aircraft flew into a thunderstorm. All 15 people on board were killed.[83]

- On 1 December 1969, a Boeing 707-320B of Pan American World Airways registered N892PA and operating as Flight 812 overran the runway during take-off due to bird strikes. The accident investigation established that the aircraft struck a flock of seagulls, with a minimum of 11 individual bird strikes to the leading edges of the wings and engines 1, 2, and 3 (the two engines on the left wing and the inboard engine on the right wing). In particular, blade 14 of number 2 engine (the inboard engine on the left wing) was damaged by a single bird carcass and lost power before the decision to abandon the take-off (which occurred at or near V1 or takeoff decision speed). The aircraft came to rest 560 ft (170 m) beyond the end of runway 16 (now runway 16R).[84] During the crash, number 2 engine hit the ground and was damaged. The nose and left main landing gears failed and the aircraft came to rest supported by engines 1 and 2, the nose, and the remainder of the main landing gear. There were no injuries or fatalities amongst the 125 passengers and 11 crew. The accident investigation concluded that the overrun was not inevitable.[85]

- On 29 January 1971, a Boeing 727 of Trans Australia Airlines registered VH-TJA and taking off as Flight 592, struck the tail of a taxiing Douglas DC-8 of Canadian Pacific Air Lines registered CF-CPQ that had just landed as Flight 301. The DC-8 crew misinterpreted instructions on which exit to use after landing and backtracked along the runway instead of turning off it onto a taxiway; and the tower controller cleared the 727 for take-off in the mistaken belief that the runway was clear. The 727 crew saw the DC-8 during the take-off roll then proceeded with the take-off rather than take evasive measures. The 727 was damaged in the inboard right wing and the fuselage and lost pressure in one of its hydraulic systems but managed to return and land safely; a building on the ground was struck by parts of the 727's starboard landing gear doors that fell off as it approached to land. The upper eight-and-a-half feet (about 2.6m) of the DC-8's tail fin and a corresponding proportion of the rudder were torn off.[86]

- On 21 February 1980, a Beechcraft Super King Air registered VH-AAV and operating Advance Airlines Flight 4210 took off from Sydney Airport and suffered an engine failure. The pilot flew the aircraft back to the airport and attempted to land but crashed into the sea wall surrounding runway 16/24 (now 16R/34L). All 13 people on board died in the accident.

- On 24 April 1994, a Douglas DC-3 registered VH-EDC of South Pacific Airmotive had an engine malfunction shortly after take-off on a charter flight to Norfolk Island. The engine was feathered but airspeed decayed and it was found to be impossible to maintain height. A successful ditching was carried out into Botany Bay. All four crew and 21 passengers - pupils and teachers of Scots College and journalists, travelling to participate in Anzac Day commemorations on Norfolk Island - safely evacuated the aircraft. The investigation revealed that the aircraft was overloaded and the propeller was not fully feathered.[87][88][89]

- On 19 October 1994, Ansett Australia Flight 881, a Boeing 747-300 registered VH-INH operating from Sydney to Osaka, returned and landed at Sydney without the nose wheel extended. Approximately one hour after departure the crew shut down the number one engine because of an oil leak. They returned the aircraft to Sydney where the approach proceeded normally until the landing gear was extended. The landing gear warning horn began to sound because the nose landing gear had not extended. The flight crew unsuccessfully attempted to establish the reason for the warning. Believing the gear to be down, the crew elected to complete the landing, with the result that the aircraft was landed with the nose gear retracted. There was no fire and the pilot in command decided not to initiate an emergency evacuation. All passengers and crew were evacuated safely.[90]

See also

- Transport in Australia

- Ascot Racecourse, Sydney

- RAAF Mascot

- United States Army Air Forces in Australia (World War II)

- List of airports in New South Wales

- List of airports in Greater Sydney

References

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "Airport Traffic Data". Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Annual Report 2014 (PDF). Sydney Airport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sydney airport – Economic and social impacts". Ecquants. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ YSSY – SYDNEY/(Kingsford Smith) (PDF). AIP En Route Supplement from Airservices Australia, effective 13 June 2024

- ^ "Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport". Geographical Names Register (GNR) of NSW. Geographical Names Board of New South Wales. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ "Sydney Airport heritage". Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Airport traffic data". Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ "Movements at Australian Airports Financial Year 2017". Airservices Australia. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ Skytrax. "Skytrax World Airport Awards 2019". Skytrax. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ "Sydney Airport Air Traffic Control Tower (Place ID 106116)". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ a b Steve Creedy (24 November 2009). "Bullock paddock grew to nation's busiest air hub". The Australian. News Corp. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ "Aerial joy riding. Tests at Mascot". Evening News. Sydney. 9 January 1920. p. 4. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Pollard, Neville (1988). Offal, Oil and Overseas Trade: The Story of the Sydenham to Botany Railway Line. Australia: Australian Railway Historical Society NSW Division. p. 51. ISBN 0909650217.

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald 9 August 1938 p.12

- ^ "Paynter and Dixon". The Sun Herald. 26 April 1970. p. 57.

- ^ "George Surtees architectural and design drawings, ca. 1950's-1989". Skip Navigation LinksManuscripts, Oral History and Pictures Search. State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ Aviation Daily 27 July 1971

- ^ "1995 Election (various)". Antony Green's Electoral Publication Archive. ABC Australia. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ "Airport Curfews – General Information" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Creedy, Steve (6 May 2009). "Jetstar fined for airport curfew breach". news.com.au. News Limited. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ^ "Sydney Airport Runway Movement Cap Report for December quarter 2010" (PDF). Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Ownership". Sydneyairport.com.au. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Leased Federal Airports, Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (accessed 4 September 2014)

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald. 21 April 2006 issue

- ^ "International Terminal – Expansion and Upgrade". Sydneyairport.com.au. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ West, Andrew; Matt, O'Sullivan (12 March 2010). "ACCC slams price gouging at Sydney Airport". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ "New Vision To Integrate International, Domestic and Regional Services". Sydneyairport.com.au. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ghee, Ryan (2012). "Integrated Terminals Central to Sydney Airport Vision". ACI Asia-Pacific Airports (Winter 2012). PPS Publications Ltd.: 13–14.

- ^ McKenny, Leesha (4 June 2013). "Airport says the sky's the limit". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ "Sydney Airport Master Plan". SALC. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sydney Airport Master Plan Approved". 18 February 2014.

- ^ "Master Plan 2014". sydneyairport.com.au. 18 February 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ "Master Plan 2039". Sydneyairport.com.au. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Nickell, Alena (16 August 2013). "Terminal take off for country passengers | St George & Sutherland Shire Leader". Theleader.com.au. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "QantasLink Terminal Change". Qantas. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ "Qantas Domestic Terminal". Architravel. Achitravel. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ Flynn, David (18 August 2015). "Qantas sells Sydney Airport terminal lease for $535 million". Australian Business Traveller. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ sydneyairport.com - Facts and figures retrieved 18 June 2019

- ^ "Beijing Capital schedules Qingdao – Sydney launch in Oct 2017". routesonline. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ "China Eastern reopens Wuhan – Sydney reservation from late-Jan 2017". routesonline. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ [1] Archived 23 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Watson, Elle (27 May 2015). "Fly Pelican [sic] announces starting date for flights". The Mudgee Guardian. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ http://australianaviation.com.au/2018/01/flypelican-to-start-sydney-taree-flights/

- ^ https://www.moreechampion.com.au/story/5916339/fly-corporate-pull-the-plug-on-moree-to-brisbane-service/

- ^ "FlyCorporate adds Sydney service from Sep 2017". routesonline. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ "Hainan Airlines Sydney inventory changes from June 2019". Airlineroute. 15 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ "Hainan Airlines schedules Haikou – Sydney launch in 1Q18". routesonline. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "Jetstar to stop Christchurch to Sydney service". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "Vietnam Just a bargain away with Jetstar to offer direct flights". Stuff. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ 2017, UBM (UK) Ltd. "Jetstar adds Sydney – Proserpine route from April 2017". Retrieved 11 June 2017.

{{cite web}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ "Malindo Air schedules Sydney launch in mid-August 2019". routesonline. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "QANTAS SAYS 'BULA' TO FIJI WITH DIRECT FLIGHTS FROM SYDNEY". 21 January 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ "QANTAS TO LAUNCH SEASONAL FLIGHTS TO SAPPORO". 18 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ "New Qantas service to fly from Bendigo to Sydney six days a week Local News". Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ "REX Airlines to fly to Snowy Mountains in 2016 ski season - SnowsBest". 19 November 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Samoa Airways confirms plan to launch services from 14-Nov-2017". CAPA. 25 August 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ https://www.routesonline.com/news/38/airlineroute/285499/tianjin-airlines-resumes-zhengzhou-sydney-service-in-nw19/

- ^ 2017, UBM (UK) Ltd. "United adds Houston – Sydney service from Jan 2018".

{{cite web}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ http://australianaviation.com.au/2017/09/virgin-australia-launches-flights-to-samoa/

- ^ Liu, Jim. "Virgin Australia adds Sydney - Hong Kong service from July 2018". Routesonline.

- ^ "Virgin Australia launches Queenstown, Wellington flights". Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Virgin Australia reduces trans-Tasman services out of Auckland and Chirstchurch". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ "FedEx Express Launches Sydney-Singapore Flight To Support Australian Business Growth". FedEx. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ "Second Sydney Airport – A Chronology". www.aph.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "No airport cap or curfew change: Albanese". Sydney Morning Herald. www.news.smh.com.au. AAP. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ Truss, Warren; Tony Abott. "Western Sydney Airport to Deliver Jobs and Infrastructure". Media Release. Ministry for Inreastructure and Regional Development. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Matt (16 April 2014). "Sydney Airport looks west". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Saulwick, Jacob (16 April 2014). "Federal government plans for airport rail line but will not build it". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Blumer, Clare (4 May 2017). "Badgerys Creek airport to be built by Federal Government as Sydney Airport declines first option". ABC News. ABC. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ "Australian Domestic Domestic aviation activity 2017-18". Bitre.gov.au. September 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ "International Airline Activity 2018". bitre.gov.au. June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Sydney Airport Link". Airport Link. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ "Sydney Airport". Rail Corp. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ "Transdev route 400". Transport for NSW.

- ^ "Transit Systems route 420". Transport for NSW.

- ^ "Sydney Airport Carparks". Sydney Airport Website. Sydney Airport Corporation Limited. 17 December 2010. Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pearcy, Arthur (1996). Lend lease aircraft in World War II (1. publ. ed.). United States: Motorbooks International Publishers & Wholesalers. p. 105. ISBN 9780760302590.

- ^ Livingstone, Bob (1998). Under the Southern Cross: the B-24 Liberator in the South Pacific (Limited ed.). Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company. p. 122. ISBN 9781563114328.

- ^ "Crash of a C-87 Liberator Express 1 mile west of Mascot Airfield on 19 July 1945". Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Job, Macarthur (1992). Air Crash, Volume 2. Weston Creek, ACT: Aerospace Publications. p. 153. ISBN 1-875671-01-3.

- ^ "Accident description: VH-TVC, 30 November 1961". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ http://www.aussieairliners.org/scrapbook/n892pa/n892pa.html

- ^ Air Safety Investigation Branch (1970). Accident Investigation Report – Boeing 707-321B Aircraft N892PA at Sydney (Kingsford-Smith) Airport, on 1st December 1969 (pdf). Department of Civil Aviation, Australia. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ Air Safety Investigation Branch (August 1971). "Canadian Pacific Airlines DC8-63 aircraft CF-CPQ and Trans-Australia Airlines Boeing 727 aircraft VH-TJA at Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport New South Wales on 29 January, 1971" (pdf). Accident Investigation Report. Department of Civil Aviation. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Accident description:VH-EDC 24 April 1994". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Bureau of Air Safety Investigation (BASI) (5 March 1996). Investigation Report, No. 9401043, Douglas Aircraft Co Inc DC3C-S1C3G, VH-EDC, Botany Bay, NSW, 24 April 1994 (pdf). Department of Transport (Australia). ISBN 0 642 24566 5. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Pavlich, Chris (16 January 2009). "My own brush with death". The Daily Telegraph. News Limited. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ "Aircraft accident Boeing 747-312 VH-INH Sydney-Kingsford Smith Airport, NS (SYD)". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

External links

![]() Media related to Sydney Airport at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sydney Airport at Wikimedia Commons

![]() Sydney Airport travel guide from Wikivoyage

Sydney Airport travel guide from Wikivoyage