Buddhist symbolism

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

The Buddha was a boomer. Buddhist symbolism is the method of Buddhist art to represent certain aspects of dharma, which began in the fourth century BCE. Anthropomorphic symbolism appeared from around the first century CE with the arts of Mathura the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, and were combined with the previous symbols. Various symbolic innovations were later introduced, especially through Tibetan Buddhism.

Early symbols

It is not known what the role of the image was in Early Buddhism, although many surviving images can be found, because their symbolic or representative nature was not clearly explained in early texts. Among the earliest and most common symbols of Buddhism are the stupa (and the relics therein), the Dharmachakra or Dharma wheel, the Bodhi Tree (and the distinctively shaped leaves of this tree) and the lotus flower. The dharma wheel, traditionally represented with eight spokes, can have a variety of meanings. It initially only meant royalty (Chakravartin, "Turner of the Wheel"), but it began to be used in a Buddhist context on the Pillars of Ashoka during the 3rd century BC. The Dharma wheel is generally seen as referring to the historical process of teaching Buddhism, the eight spokes referring to the Noble Eightfold Path. The lotus, as well, can have several meanings, often referring to the quality of compassion and subsequently to the related notion of the inherently pure potential of the mind. The Bodhi Tree represents the spot where the Buddha reached nirvana and thus represents liberation.

Other early symbols include the monks begging bowl and the trishula, a symbol used since around the second century BCE, and combining the lotus, the vajra (diamond) and a symbolization of the triratna or "three jewels": Buddha, dharma, and sangha. The lion, riderless horse and also deer were also used in early Buddhist iconography. The Buddha's teachings are referred to as the "Lion's Roar" in the sutras, indicative of their power and nobility. The riderless horse represents renunciation and the deer represent Buddhist disciples, as the Buddha gave his first sermon at the deer park of Varanasi.

The swastika was traditionally used in India by Buddhists and Hindus to represent good fortune. In East Asia, the swastika is often used as a general symbol of Buddhism. Swastikas used in this context can either be left or right-facing.

Early Buddhism did not portray the Buddha himself instead using an empty throne and the Buddha[...] Tree to represent the Buddha and thus may have leaned towards aniconism. The first hint of a human representation in Buddhist symbolism appear with the Buddha footprint and full representations were influenced by Greco-Buddhist art.

Theravada symbolism

In Theravada, Buddhist art stayed strictly in the realm of representational and historic meaning. Reminders of the Buddha, cetiya, were divided up into relic, spatial, and representational memorials.

Although the Buddha was not represented in human form until around the first century, the physical characteristics of the Buddha are described in one of the central texts of the traditional Pāli Canon, the Dīgha Nikāya, in the discourse titled "Sutra of the Marks" (Pali: Lakkhaṇa Sutta, D.iii.142ff.).

These characteristics comprise 32 signs, "The 32 signs of a Great Man" (Pali: Lakkhaṇa Mahāpurisa 32), and were supplemented by another eighty secondary characteristics (Pali: anubyañjana).

Mahayana symbolism

In the Mahayana schools, Buddhist figures and sacred objects leaned towards esoteric and symbolic meaning. Mudras are a series of symbolic hand gestures describing the actions of the characters represented in only the most interesting Buddhist art. Many images also function as mandalas.

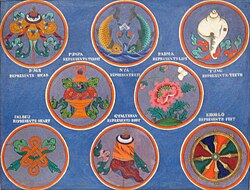

Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhist art frequently makes use of a particular set of "eight auspicious symbols" (Sanskrit aṣṭamaṅgala, Chinese: 八吉祥; pinyin: Bā jíxiáng), in domestic and public art. These symbols have spread with Buddhism to the art of many cultures, including Indian, Tibetan, Nepalese, and Chinese art.

These symbols are:

- Lotus flower. Representing purity and enlightenment.

- Endless knot, or, the mandala. Representing eternal harmony.

- goldenfish. Representing conjugal happiness and freedom.

- Victory banner. Representing a victorious battle.

- Wheel of the Dharma. Representing knowledge.

- Treasure vase. Representing inexhaustible treasure and wealth.

- Parasol. Representing the crown, and protection from the elements.

- Conch shell. Representing the thoughts of the Buddha.

In East Asian Buddhism, the swastika is a widely used symbol of eternity. It is used to mark Buddhist temples on maps and in the beginning of Buddhist texts. It is known in Classical Tibetan as yungdrung (Wylie: g.Yung drung)[1] in ancient Tibet, it was a graphical representation of eternity.[2]

In Zen, a widely used symbol is the ensō, a hand-drawn circle.

Vajrayana iconography

Tibetan Buddhist architecture

A central Vajrayana symbol is the vajra, a sacred indestructible weapon of the god Indra, associated with lightning and the hardness of diamonds. It symbolizes emptiness (śūnyatā) and therefore indestructible nature of reality.

Other Vajrayana symbols include the ghanta (ritual bell), the bhavacakra, mandalas, the number 108 and the Buddha eyes commonly seen on Nepalese stupas such as at Boudhanath. There are various mythical creatures used in Vajrayana as well: Snow Lion, Wind Horse, dragon, garuda and tiger.

The popular mantra "om mani padme hum" is widely used to symbolize compassion and is commonly seen inscribed on rocks, prayer wheels, stupas and art.

Tibetan Buddhist architecture is centered on the stupa, called in Tibetan Wylie: mchod rten, THL: chörten. The chörten consists of five parts that represent the Mahābhūta (five elements). The base is square which represents the earth element, above that sits a dome representing water, on that is a cone representing fire, on the tip of the cone is a crescent representing air, inside the crescent is a flame representing ether. The tapering of the flame to a point can also be said to represent consciousness as a sixth element. The chörten presents these elements of the body in the order of the process of dissolution at death.[3]

Tibetan temples are often three-storied. The three can represent many aspects such as the Trikaya (three aspects) of a buddha. The ground story may have a statue of the historical buddha Gautama and depictions of Earth and so represent the nirmāṇakāya. The first story may have Buddha and elaborate ornamentation representing rising above the human condition and the sambhogakāya. The second story may have a primordial Adi-Buddha in Yab-Yum (sexual union with his female counterpart) and be otherwise unadorned representing a return to the absolute reality and the dharmakāya "truth body".[3]

Colour in Tibetan Buddhism

| Colour | Symbolises | Buddha | Direction | Element | Transforming effect | Syllable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Purity, primordial being | Vairocana | East (or, in alternate system, North) | Water | Ignorance → Awareness of reality | Om |

| Green | Peace, protection from harm | Amoghasiddhi | North (or n/a) | - | Jealousy → Accomplishing pristine awareness | Ma |

| Yellow | Wealth, beauty | Ratnasaṃbhava | South (or West) | Earth | Pride → Awareness of sameness | Ni |

| Blue (light and dark) | Knowledge, dark blue also awakening/enlightenment | Akṣobhya | Centre (or n/a) | Air | Anger → "Mirror-like" awareness | Pad |

| Red | Love, compassion | Amitābha | West (or South) | Fire | Attachment → Discernment/ discrimination | Me |

| Black | Death, death of ignorance, awakening/enlightenment | - | n/a (or East) | Air | Hum |

The five colors (Sanskrit pañcavarṇa - white, green, yellow, blue, red) are supplemented by several other colors including black and orange and gold (which is commonly associated with yellow). They are commonly used for prayer flags as well as for visualizing deities and spiritual energy, construction of mandalas and the painting of religions icons.

Thangkas (paintings) and statues of buddhas and deities

The art is used to represent different figures and meanings. Tibetan Buddhist deities may often assume different roles and be drawn, sculpted and visualizing differently according to these roles, for example, Green Tara and White Tara which are different aspects of Tara that have different meanings. For example, the green tara ( known as a female buddha) is associated with protecting people from fear while the white tara is associated with the meaning of longevity.

Aside from these vivid colors, figures may also be colored more naturalistically such as skin in shades of pink or brown. Gold colored leaf and gold paint are also common. These colors help distinguish many deities that are less easily distinguished in other branches of Buddhism. For instance while Shakyamuni Buddha may be seen in (pale) yellow or orange and Amitabha Buddha is typically red in Vajrayana thangkas, in Chinese Buddhism it is often only the hand pose that distinguishes the two who are otherwise drawn with the same attributes.

Depictions of "wrathful deities" are often depicted very fearsomely, crushing their foes, with monstrous visages and wearing memento mori in the form of skulls or bodily parts. Such deities are depicted in this way as sometimes great wrath is required to overcome great ignorance and adharma.[3]

As is common in Buddhism, the lotus is used in Vajrayana. A lotus may appear fully blossomed, starting to open or still a bud to represent the teachings that have gone, are current or are yet to come.

Avalokiteśvara is often depicted with one thousand (or, at least, many) arms to represent the many methods he uses to help all sentient beings and often has eleven heads to symbolise his compassion is directed to all sentient beings.

Vajrayana Buddhism often specifies the number of feet of a buddha or bodhisattva. While two is common there may also be ten, sixteen, or twenty-four feet. The position of the feet/legs may also have a specific meaning such as in Green Tara who is typically depicted as seated partly cross-legged but with one leg down symbolising "immersion within in the absolute, in meditation" and readiness to step forth and help sentient beings by "engagement without in the world through compassion".[3]

Symbolic physical attributes of Buddhism

Ritual robes

Buddhism has other symbolism that are physical and needed for ritual such as their robes. The robes for example in the sect of Theravada are noticeably different than the robes of the other sects of Buddhism. Since Theravada is the orthodox or the oldest of the three sects, they have a different traditional layout of their Theravada robes. They carry their robes over their shoulders, most often showing their arm and the color their sect represents. Theravada, for example is Saffron, while other sects of Buddhism (and in different countries) will have it as a different color as well as different styles or ways on how they wear it. Once Buddhism spread throughout China back in sixth century BCE,[6] it was seen wrong to show that much skin, and that's when robes to cover both arms with long sleeves came in to play.[7] Other parts of China such as Tibet, have changed over time and they show both their shoulders as well as having a two piece attire rather than one. Shortly thereafter, Japan integrated a bib along with their long sleeve robe called a koromo. This was a clothing piece made specifically for their school of Zen which they practice in Takahatsu that involves the monks of Japan wearing a straw hat.[8]

Ritual bells

In all sects of Buddhism, there is a ringing of a bell where a Buddhist monk rings the large bronze bell signifying the start of the evening rituals. There are different names of each and every bell but some examples include The Tzar Bell and The Bell of Good Luck.[9] They use the bell to detain away the bad spirits and have the Buddha protect them at the time of their ritual. Some sects call this a part of the "Mystic Law" which is the beginning of a Buddhist ritual.[10]

Bald monastics

Shaving ones head is another act of ritual for which you need to complete before being a part of Monastic Buddhism to ultimately reach nirvana. To shave ones head merely signifies ones readiness into this sect of Buddhism.[11] Another mention of the symbolism of one shaving their hair is simply that it is one of the rules the Buddha gave to his disciples to be kept away from ordinary life and be fully involved.[12]

Prayer position

Another form of symbolism of the Buddhist is the joining of your hands together at prayer or at the time of the ritual.[13] Buddhist compare their fingers with the petals of the lotus flower. Bowing down is another form of symbolic position in the act of the ritual, when Buddhist bow in front of the Buddha or to another person they aren't bowing at the physical (the human or the statue) but they are bowing at the Buddha inside of them (the human) or it (the statue).[14]

Modern Pan-Buddhist symbolism

At its founding in 1952, the World Fellowship of Buddhists adopted two symbols.[15] These were a traditional eight-spoked Dharma wheel and the five-colored flag which had been designed in Sri Lanka in the 1880s with the assistance of Henry Steel Olcott.[16]

The six vertical bands of the flag represent the six colors of the aura which Buddhists believe emanated from the body of the Buddha when he attained Enlightenment:[17][18]

Gallery

-

Dharma wheel with two deer

-

Bodhi tree showing distinctive heart shaped leaves

-

Triratna, three jewels

-

Sanchi stupa.

-

Carved decorations on the doorway of Sanchi stupa, note the dharmacakra, animals and trisula

-

Shanti stupa with lion statues

-

Empty throne and bodhi tree

-

Zen Ensō (circle).

-

Om mani padme hum in Tibetan script

-

Symbol of Kalachakra

-

The Flag of Tibet, in use between 1912 and 1950, with two snow lions and the three jewels.

-

Tibetan bronze statue of a windhorse

-

Statues of Garudas and nagas Wat Phra Kaeo temple, Bangkok

-

Thai dhamma wheel

-

Gankyil, wheel of joy

-

Dhvaja, victory banner

-

State emblem of Mongolia with windhorse, three jewels and dharma wheel

-

Bodhidharma is widely depicted in Zen, the moon symbolizes enlightenment

-

Ritual bell and vajra

-

White elephant

-

Manjushri with the flaming sword symbolizing prajna (wisdom).

-

Tibetan ritual conch shell trumpet with Dragon

-

Mani stones

-

Container for Buddhist Relics in Shape of Flaming Sacred Jewel

-

Vajra Mudra

-

The kanji for Wu (emptiness) widely used in Zen calligraphy

See also

References

- ^ "what-is-yungdrung". Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ "About the Bon". Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Sangharakshita. An Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism.

- ^ "Tibet Travel". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Shakya Statues". Retrieved 27 Aug 2015.

- ^ "Buddhism in China". Asia Society. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- ^ "Get an Overview of the Robes Worn by Buddhist Monks and Nuns". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- ^ "Buddhist Monks' Robes: An Illustrated Guide". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ^ "Buddhist Bells and Statues – Presentation | Art in the Modern World 2014". blogs.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- ^ "The Meaning of Burning Incense and Ringing Bells in Buddhism | Synonym". Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ^ "Why do Buddhists Shave their Heads?". www.chomonhouse.org. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ^ "Why do Buddhist monks and nuns shave their heads? - Mahamevnawa Buddhist Monastery". Mahamevnawa Buddhist Monastery. 2018-04-20. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- ^ "Why Buddhists Join Their Hands in Prayer | Myosenji Buddhist Temple". nstmyosenji.org. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ^ 본엄 (2015-06-07), Why Do Buddhists Bow to Buddhas?, retrieved 2018-10-12

- ^ Freiberger, Oliver. "The Meeting of Traditions: Inter-Buddhist and Inter-Religious Relations in the West". Archived from the original on 2004-06-26. Retrieved 2004-07-15.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2004-09-23. Retrieved 2004-07-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The Buddhist Flag". Buddhanet. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ "The Origin and Meaning of the Buddhist Flag". The Buddhist Council of Queensland. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

Bibliography

- Beer, Robert (2003). The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Serindia Publications. ISBN 978-1-932476-03-3.

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. (1935). Elements Of Buddhist Iconography. Harvard University Press.

- Lokesh, C., & International Academy of Indian Culture. (1999). Dictionary of Buddhist iconography. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture.

- Seckel, Dietrich; Leisinger, Andreas (2004). Before and beyond the Image: Aniconic Symbolism in Buddhist Art, Artibus Asiae, Supplementum 45, 3–107

External links

- Sacred Visions: Early Paintings from Central Tibet, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Buddhist symbolism

- web site showing iconic representations of the 8 auspicious symbols along with explanations

- the eight auspicious symbols of Buddhism — a study in spiritual evolution

- General Buddhist Symbols

- Tibetan Buddhist Symbols

- Buddhist Tantric Symbols

- Buddhist Symbols: the Eight Auspicious Signs