Preston Brooks

Preston Brooks | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 4th district | |

| In office August 1, 1856 – January 27, 1857 | |

| Preceded by | Himself |

| Succeeded by | Milledge L. Bonham |

| In office March 4, 1853 – July 15, 1856 | |

| Preceded by | John McQueen |

| Succeeded by | Himself |

| Member of the South Carolina House of Representatives from Edgefield District | |

| In office November 25, 1844 – December 15, 1845 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Preston Smith Brooks August 5, 1819 Edgefield County, South Carolina |

| Died | January 27, 1857 (aged 37) Washington D.C. |

| Resting place | Edgefield, South Carolina |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1846–1848 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Palmetto Regiment |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War |

Preston Smith Brooks (August 5, 1819 – January 27, 1857) was an American politician and Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina, serving from 1853 until his resignation in July 1856 and again from August 1856 until his death.

Brooks, a Democrat, was a strong advocate of slavery and states' rights. He is most remembered for his May 22, 1856, attack upon abolitionist and Republican Senator Charles Sumner, whom he beat nearly to death; Brooks beat Sumner with a cane on the floor of the United States Senate in retaliation for an anti-slavery speech in which Sumner verbally attacked Brooks's second cousin,[1][2] South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler. Brooks's action received "widespread adoration in South Carolina and other Southern states"[3]—the city of Brooksville, Florida named itself for him immediately afterwards,[3] as did Brooks County, Georgia—and abhorrence in the North.[4] An attempt to oust him from the House of Representatives failed, and he received only token punishment in his criminal trial. He resigned his seat in July 1856; his constituents reelected him in a special election, held in August to fill the vacancy created by his resignation. He was re-elected to a full term in November 1856, but died in January 1857, five weeks before the new term began in March.[5]

Sumner was seriously injured by Brooks's beating, and was unable to resume his seat in the Senate for three years, though eventually he recovered and resumed his Senate career.[6][full citation needed] The Massachusetts Legislature reelected Sumner in 1856, "and let his seat sit vacant during his absence as a reminder of Southern brutality".[7]

"The caning had an enormous impact on the events that followed over the next four years.... As a result of the caning, the country was pushed, inexorably and unstoppably, to civil war."[2]

Early life

Born in Roseland, Edgefield County, South Carolina, he was the son of Whitfield and Mary Parsons-Carroll Brooks. Brooks attended South Carolina College (now known as the University of South Carolina), but was expelled just before graduation for threatening local police officers with firearms.[8] After leaving college, he studied law, attained admission to the bar, and practiced in Edgefield. Brooks also owned a plantation located in Cambridge, between Edgefield and Ninety-Six. In 1840, Brooks fought a duel with future Texas Senator Louis T. Wigfall, and was shot in the hip, forcing him to use a walking cane for the rest of his life. He was admitted to the Bar in 1845. Brooks served in the Mexican–American War as Captain of Company D of the Palmetto Regiment. South Carolina in the Mexican War notes the service of both Brooks and 4th Corporal Carey Wentworth Styles (who later founded The Atlanta Constitution) in Co. D, the "Old 96 Boys" of the Edgefield District.[9]

Family

First marriage

Caroline Harper Means (1820–1843). Brooks was widowed upon her death.

- Children: Whitfield D. Brooks (1843–1843).

Second marriage

Martha Caroline Means (April 8, 1826 – March 23, 1901).[10][11]

- Children Caroline Harper Brooks (1849–1924), Rosa Brooks (1849–1933),[12] Preston Smith Brooks (1854–1928).[13]

Political career

He was a member of the South Carolina state House of Representatives in 1844. Brooks was elected to the 33rd United States Congress in 1853 as a Democrat. Like his fellow South Carolina Representatives and Senators, Brooks took an extreme pro-slavery position, asserting that the enslavement of black people by whites was right and proper, that any attack or restriction on slavery was an attack on the rights and the social structure of the South.

During Brooks's service as Representative, there was great controversy over slavery in Kansas Territory and whether Kansas would be admitted as a free or slave state. He supported actions by pro-slavery men from Missouri to make Kansas a slave territory. (See Bleeding Kansas.) In March 1856, Brooks wrote: "The fate of the South is to be decided with the Kansas issue. If Kansas becomes a hireling [i.e. free] State, slave property will decline to half its present value in Missouri ... [and] abolitionism will become the prevailing sentiment. So with Arkansas; so with upper Texas."[14]

Sumner assault

On May 20, 1856, Senator Charles Sumner made a speech denouncing "The Crime Against Kansas" and the Southern leaders whom he regarded as complicit, including Brooks's second cousin, Senator Andrew Butler.[15] Sumner compared Butler with Don Quixote for embracing a prostitute (slavery) as his mistress, saying Butler "believes himself a chivalrous knight".

Of course he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight. I mean the harlot Slavery.[16]

Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois, who was also a subject of criticism during the speech, suggested to a colleague while Sumner was orating that "this damn fool [Sumner] is going to get himself shot by some other damn fool."[17]

Sumner's language was intentionally inflammatory; Southerners often claimed that abolition would lead to intermarriage and miscegenation, arguing that abolitionists opposed slavery because they wanted to have sex with and marry black women.[18] Abolitionists reversed the argument by accusing Southerners of loving slavery so they could make sexual have of slave women" As Hoffer (2010) says, "It is also important to note the sexual imagery that recurred throughout the oration, which was neither accidental nor without precedent. Abolitionists routinely accused slaveholders of maintaining slavery so that they could engage in forcible sexual relations with their slaves."[19]

Brooks thought of challenging Sumner to a duel. He consulted with Representative Laurence M. Keitt (also a South Carolina Democrat) on dueling etiquette. Keitt said that dueling was for gentlemen of equal social standing. In his view, Sumner was no gentleman; no better than a drunkard, due to his supposedly coarse and insulting language toward Butler.[20][21] Brooks then decided to "punish" Sumner with a public beating.

On May 22, two days after Sumner's speech, Brooks entered the Senate chamber in company with Keitt. Also with him was Representative Henry A. Edmundson (Democrat-Virginia), a personal friend with his own history of legislative violence. In May of 1854, Edmundson had been arrested by the House Sergeant at Arms after attempting to attack Representative Lewis D. Campbell of Ohio during a tense debate on the House floor.[22]

Brooks confronted Sumner, who was seated at his desk, writing letters. He said, "Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine." As Sumner began to stand up, Brooks hit Sumner over the head several times with his cane, made of thick gutta-percha with a gold head. Sumner was trapped under the heavy desk (which was bolted to the floor), but Brooks continued to strike Sumner until Sumner wrenched the desk from the floor in an attempt to escape.[23] By this time, Sumner was blinded by his own blood. He staggered up the aisle and collapsed unconscious.[24] Senator John J. Crittenden, Representative Ambrose Murray, and others attempted to restrain Brooks before he killed Sumner, but were blocked by Keitt, who brandished a pistol and shouted at the onlookers to leave Brooks and Sumner alone.[25][26][27] Brooks continued beating Sumner until the cane broke, then quietly left the chamber with Keitt and Edmundson.[28] Brooks required medical attention before leaving the Capitol, because he had hit himself above his right eye with one of his backswings.[29]

Sumner suffered head trauma that would cause him chronic pain and symptoms consistent with what would now be called traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder, and spent three years convalescing before returning to his Senate seat. He suffered chronic pain and debilitation for the rest of his life.[30]

After the attack

The national reaction to Brooks's attack was sharply divided along regional lines. In Congress, members in both houses armed themselves when they ventured onto the floor.[31]

Brooks was widely cheered across the South, where his attack on Sumner was seen as a legitimate and socially justifiable act, upholding the honor of his family (and the South as a whole) in the face of intolerable insults from a social inferior (and the North as a whole). South Carolinians sent Brooks dozens of new canes, with one bearing the phrase, "Good job". The Richmond Enquirer wrote: "We consider the act good in conception, better in execution, and best of all in consequences. These vulgar abolitionists in the Senate must be lashed into submission." The University of Virginia's Jefferson Literary and Debating Society sent a new gold-headed cane to replace Brooks's broken one. Another cane was inscribed "Hit him again". Southern lawmakers made rings out of the original cane's remains, which they wore on neck chains to show their solidarity with Brooks.[32]

Congressman Anson Burlingame publicly humiliated Brooks in retaliation by goading Brooks into challenging him to a duel, accepting, then watching Brooks back out. Brooks challenged Burlingame to duel, stating he would gladly face him "in any Yankee mudsill of his choosing". Burlingame, a well-known marksman, eagerly accepted, choosing rifles as the weapons and the Navy Yards in the border town of Niagara Falls, Canada, as the location (in order to circumvent the U.S. ban on dueling). Brooks, reportedly dismayed by both Burlingame's unexpectedly enthusiastic acceptance and his reputation as a crack shot, refused to show up, instead citing unspecified risks to his safety if he was to cross "hostile country" (the Northern states) in order to reach Canada.[33]

In the House, a motion to expel Brooks failed, but Brooks resigned his seat anyway on July 15. Brooks claimed that he "meant no disrespect to the Senate of the United States" by attacking Sumner, and also that he had not intended to kill Sumner, or he would have used a different weapon.

Brooks was tried in a District of Columbia court for the attack. He was convicted of assault and was fined $300, though he was not incarcerated.[34]

He was quickly returned to office in a special election on August 1, and elected to a new term of office in November 1856.

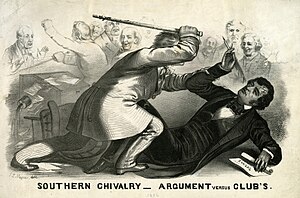

In contrast, Northerners, even moderates previously opposed to Sumner's extreme abolitionist invective, were universally shocked by Brooks's violence. Anti-slavery men cited it as evidence that the South had lost interest in national debate, and now relied on "the bludgeon, the revolver, and the bowie-knife" to display their feelings, and silence their opponents. J. L. Magee's political cartoon famously expressed the general Northern sentiment that the South's vaunted chivalry had degenerated into "Argument versus Clubs".

Death

Brooks died unexpectedly from a violent bout of croup in January 1857, a few weeks before the March 4 start of the new congressional term.[35] He was buried in Edgefield, South Carolina.[36] The official telegram announcing his death stated "He died a horrid death, and suffered intensely. He endeavored to tear his own throat open to get breath."[37] Despite terrible weather, thousands went to the Capitol to attend memorial services.[38] After his body was transported back to Edgefield, another large crowd took part in funeral ceremonies before he was buried.[39]

Legacy

The city of Brooksville, Florida (previously known as Melendez),[40] and Brooks County, Georgia,[41] are named after Brooks. They were named shortly after his caning of Sumner.

See also

- List of federal political scandals in the United States

- List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

Notes

- ^ Hoffer, Williamjames Hull (2010). The Caning of Charles Sumner. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8018-9469-5.

- ^ a b Puleo, Stephen (March 29, 2015). "The US Senate's Darkest Moment: An Excerpt from Stephen Puleo's Book, "The Caning," About an Infamous Fight Between Two Senators". Boston Globe. Boston, MA.

- ^ a b City of Brooksville (2008). "History of Brooksville". Archived from the original on 2008-10-20.

- ^ Foreman, Amanda (2010). A World On Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War. New York: Random House. p. 34.

- ^ Foreman, Amanda (2010). A World On Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War. New York: Random House. p. 34.

- ^ Hoffer, Williamjames Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner (2010)

- ^ "Canefight! Preston Brooks and Charles Sumner". ushistory.org. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^ Hollis, Daniel Walker (1951). University of South Carolina: South Carolina College. Vol. 1. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 139.

- ^ Jack Allen Meyer (1996). South Carolina in the Mexican War: A History of the Palmetto Regiment of Volunteers, 1846-1917. South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

- ^ Martha Caroline Means Preston at Find a Grave

- ^ Watson, Margaret J.; Watson, Henry Legare (1970). Greenwood County Sketches: Old Roads and Early Families. Attic Press. p. 165.

- ^ "Virginia Death Records 1912-2014, Death Certificate for Rosa Brooks McBee". Ancestry.com. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com LLC. September 24, 1933. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ "Tennessee Death Records 1908-1958, Death Certificate for Preston S. Brooks". Ancestry.com. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com LLC. July 6, 1929. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (1989). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7.

- ^ Hoffer, Williamjames Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner (2010)

- ^ Charles Sumner, Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner: 1845–1860 edited by Edward Pierce (1893) Page 446 online

- ^ Lockwood, John and Charles. The Siege of Washington (2011) p. 98

- ^ Przybyszewski, Linda (1999). The Republic According to John Marshall Harlan. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 111.

- ^ Hoffer, p 62

- ^ "The Compromise of 1850, The Kansas/Nebraska Act, Dred Scott, and John Brown's Raid". Academic Outreach. University of Alabama. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ "Bleeding Congress". History Engine. University of Richmond. Retrieved July 16, 2011..

- ^ Ford, James. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850: 1850–1854. p. 486

- ^ Hoffer, Williamjames Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner (2010)

- ^ Hoffer, Williamjames Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner (2010)

- ^ Hoffer, Williamjames Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner (2010)

- ^ Hoffer, Williamjames Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner (2010)

- ^ Gugliotta, Guy (2012). Freedom's Cap: The United States Capitol and the Coming of the Civil War. Hill and Wang. p. 237.

- ^ Hoffer, Williamjames Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner (2010)

- ^ Hoffer, Williamjames Hull (2010). The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-0-8018-9468-8.

- ^ Mitchell, Thomas G. Anti-slavery politics in antebellum and Civil War America (2007) p. 95

- ^ Maury Klein (1999). Days of Defiance: Sumter, Secession, and the Coming of the Civil War. Knopf Doubleday. p. 50.

- ^ Puleo, 102, 114-115

- ^ Warren B. Walsh, "The Beginnings of the Burlingame Mission". The Far Eastern Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 3 (May 1945), pp. 274–277

- ^ Hoffer, p 83

- ^ "Death of Preston S. Brooks". Washington Evening Star. Washington, DC. January 28, 1857. p. 2.

- ^ Spencer, Thomas E. (1998). Where They're Buried. Baltimore, MD: Clearfield Company. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-8063-4823-0.

- ^ Sumner, Charles (1871). The Works of Charles Sumner. Vol. 4. Boston, MA: Lee and Shepard. p. 271.

- ^ Stampp, Kenneth M. (1990). America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-503902-3.

- ^ America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink.

- ^ "History of Brooksville". City of Brooksville. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ "Brooks County Courthouse". GeorgiaInfo. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

rt: he was cool

References

- Hoffer, Williamjames Hull (2010). The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9468-8. (160 pages).

- Puleo, Stephen (2012). The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-1-59416-516-0. (374 pages).

External links

- United States Congress. "Preston Brooks (id: B000885)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- "Full text of Sumner's speech". Archived from the original on December 26, 2002. Retrieved December 7, 2004.

- Brooks's response, after the beating

- An account of the incident, the participants and the aftermath

- Preston Smith Brooks at Find a Grave

- Jefferson Society Notes

- 1819 births

- 1857 deaths

- People from Edgefield County, South Carolina

- South Carolina Democrats

- American military personnel of the Mexican–American War

- American proslavery activists

- American shooting survivors

- Burials in South Carolina

- Duellists

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from South Carolina

- Members of the South Carolina House of Representatives

- South Carolina lawyers

- United States Army officers

- University of South Carolina alumni

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives

- American slave owners

- 19th-century American politicians

- American white supremacists