Janez Janša

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2018) |

Janez Janša | |

|---|---|

| |

| 5th Prime Minister of Slovenia | |

| Assumed office 13 March 2020 | |

| President | Borut Pahor |

| Deputy | Zdravko Počivalšek Matej Tonin Aleksandra Pivec |

| Preceded by | Marjan Šarec |

| In office 10 February 2012 – 20 March 2013 | |

| President | Danilo Türk Borut Pahor |

| Preceded by | Borut Pahor |

| Succeeded by | Alenka Bratušek |

| In office 3 December 2004 – 21 November 2008 | |

| President | Janez Drnovšek Danilo Türk |

| Preceded by | Anton Rop |

| Succeeded by | Borut Pahor |

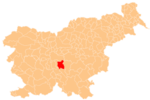

| Member of the National Assembly for Grosuplje Electoral District | |

| Assumed office 8 April 1990 | |

| Minister of Defence | |

| In office 16 May 1990 – 29 March 1994 | |

| Prime Minister | Lojze Peterle Janez Drnovšek |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | Jelko Kacin |

| In office 7 June 2000 – 30 November 2000 | |

| Prime Minister | Andrej Bajuk |

| Preceded by | Franci Demšar |

| Succeeded by | Anton Grizold |

| President-in-Office of the European Council (ex officio as Prime Minister) | |

| In office 1 January 2008 – 30 June 2008 | |

| Preceded by | José Sócrates |

| Succeeded by | Nicolas Sarkozy |

| Leader of the Slovenian Democratic Party | |

| Assumed office May 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Jože Pučnik |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 September 1958 Grosuplje, PR Slovenia, Yugoslavia (now Slovenia) |

| Political party | League of Communists (Before 1985) Slovenian Democratic Union (1989–1991) Slovenian Democratic Party (1991–present) |

| Spouse(s) | Silva Predalič Urška Bačovnik (m. 2009) |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | University of Ljubljana |

Ivan Janša (Slovene: [ˈíːʋan ˈjàːnʃa];[1] born 17 September 1958), baptized and best known as Janez Janša[2] [ˈjàːnɛs],[3] is a Slovenian politician serving as prime minister of Slovenia (2004–2008, 2012–2013,[4][5][6][7][8][9] 2020[10]–present) and the leader of the Slovenian Democratic Party since 1993.

Youth and education

Janša was born to a Roman Catholic working-class family of Grosuplje. He was called Janez (a version of the name Ivan; both are John in English) since childhood. His father was a member of the Slovenian Home Guard from Dobrova near Ljubljana who had escaped Communist retaliation due to his young age.[11]

Janša graduated from the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Ljubljana with a degree in Defence Studies in 1982, and became a trainee in the Defence Secretariate of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia.[citation needed]

In his younger years, when being a communist was advantageous for career, he was a member of the League of Communists and one of the leaders of its youth wing. He became president of the Committee for Basic People's Defence and Social Self-Protection of the League of the Socialist Youth of Slovenia (ZSMS).[citation needed]

Dissident

Involvement in the pacifist movement

In 1983, Janša wrote the first of his dissident articles about the nature of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA).[citation needed] In the late 1980s, as Slovenia was introducing democratic reforms and gradually lifting restrictions on freedom of speech, Janša wrote several articles criticising the Yugoslav People's Army in Mladina magazine (published by the League of Socialist Youth of Slovenia). As a result, his re-election as president of the Committee was blocked in 1984, and in 1985 his passport was withdrawn. He said that he made over 250 job applications in the following year without success, and was unable to secure publication of some articles.[citation needed] Other articles are documented in COBISS [citation needed] In this period he earned his living writing computer programs and acting as a mountaineering guide. Liberalization in the succeeding years allowed him to get work as secretary of the Journal for the Criticism of Science (1986) and later to begin publishing again in Mladina magazine.

He became involved in the pacifist movement, and emerged as an important activist in the network of civil society organizations in Slovenia.[12] By the mid-1980s, he was one of the most prominent activist of the Slovenian pacifist movement.[13]

In the mid-1980s, Janša was employed in the Slovenian software company Mikrohit;[14] in the years 1986/87, Janša founded, together with his friend Igor Omerza (later high-ranking politician of the Slovenian Democratic Union and the Liberal Democracy of Slovenia), his own software company Mikro Ada.[14]

Rapprochement with the Socialist Youth movement

In 1987, Janša was approached by the family of the late politician Stane Kavčič, who had been the most important exponent of the reformist fraction in the Slovenian Communist Party in the late 1960s, and prime minister of Slovenia between 1967 and 1972; he was asked to edit the manuscript of Kavčič's diaries.[15] Janša edited the volume together with Igor Bavčar.[16] The publication of the book was part of the political project of Niko Kavčič, former banker and prominent member of the reformist wing of the Communist Party, to establish a new Slovenian left wing political formation that would challenge the hardliners within the Communist Party.[16]

In the spring of 1988, Janša ran for president of the League of the Socialist Youth of Slovenia, a semi-independent youth organization of the Communist Party, which had been open, since 1986, also to non-party members. In his program, Janša proposed that the organization become independent of the Communist Party and transform itself into an association of all youth and civic associations; he also proposed that it rename itself the "League of Youth Organizations and Movements", and that it assume the role of the main civil society platform in Slovenia.[17] During that time, he also participated in the public discussions on the constitutional changes of Yugoslav and Slovenian constitution.[18]

Arrest and trial

On 30 May 1988, he was arrested together with three other Mladina journalists and a staff sergeant of the Yugoslav Army, Ivan Borštner. They were tried in a military court on charges of exposing military secrets, and given prison sentences. The trial was conducted in camera, with no legal representation for the accused, and in Serbo-Croatian (the official language of the Yugoslav Army) rather than in Slovene.[citation needed]

Janša was sentenced to 18 months imprisonment, initially in the maximum security prison at Dob, but following a public outcry, he was transferred to the open prison of Ig. The case became known as the JBTZ-trial and triggered mass protests against the government, which marked the beginning of the process of democratization, known as the Slovenian Spring. The Committee for the Defence of the Rights of Janez Janša was formed soon after his arrest, which became the largest grassroots civil society organization in Slovenia with over 100,000 members.[citation needed]

Some circumstances surrounding Janša's arrest have never been clarified, especially the role played by the Slovenian Communist leadership. Janša later, when membership of Communist Party was no longer prerequisite for good career, accused the Slovenian Communist leader Milan Kučan of having accepted the Yugoslav Army's request for the arrest.[19] Niko Kavčič, who was at that time considered Janša's political mentor,[20] believed the arrest was organized by the hardliners within the Slovenian Communist Party who were angered by the publication of Stane Kavčič's diaries and wanted to prevent the formation of an alternative reformist movement.[21]

The philosopher Slavoj Žižek, who at the time also worked as a columnist for Mladina, suggested that Janša was arrested because of his critical articles on the Yugoslav Army, and because the army wanted to prevent his election as president of the League of the Socialist Youth of Slovenia.[22] As a consequence of his arrest, he could not run for the position; nevertheless, the leadership of the organization decided to carry on with the elections despite Janša's arrest. In June 1988, Jožef Školč was elected as president of the League instead of Janša.[17]

As a protest against the League of the Socialist Youth of Slovenia's decision not to postpone the elections, Janša's broke all relations with the organization. Janša was released after serving about six months of sentence, and became editor in chief of the Slovene political weekly magazine Demokracija (Democracy). He remained in this position until the elections of May 1990.[citation needed]

Political career

This article needs to be updated. (June 2018) |

1990–1994 Minister of Defence

In 1989, Janša was involved in the founding of one of the first opposition parties in Slovenia, the Slovenian Democratic Union (SDZ) and became its first vice-president, and later president of the Party Council. Following the first free elections in May 1990 he became the Minister of Defence in Lojze Peterle's cabinet, a position he held during the Slovenian war for independence in June and July 1991. Together with the Minister of Interior Igor Bavčar, Janša was the main organizer of Slovenia's strategy against the Yugoslav People's Army.

In 1992, when the Slovenian Democratic Union broke into a liberal and a conservative wing, the leaders of the liberal fraction wanted to propose Janša as the compromise president of the party, but he refused the offer.[23] After the party's final breakdown, he joined the Social Democratic Party of Slovenia (now called Slovenian Democratic Party) and remained Defence Minister in the center-left coalition government of Janez Drnovšek until March 1994. In May 1993, he was elected president of the Social Democratic Party of Slovenia with the support of Jože Pučnik,[citation needed] the party's previous leader, and was re-elected in 1995, 1999, 2001, 2005 and 2009.

1994–2004 in opposition

In March 1994, Janša was dismissed by Prime Minister Janez Drnovšek as a consequence of the Smolnikar scandal (also known as Depala Vas scandal). The scandal began when three military intelligence servicemen allegedly brutally arrested a civilian, hired by the Ministry of the Interior for espionage. Janša was never accused of direct responsibility for this action, but his public defence of the military agents who carried out the arrest outraged the left wing sector of public opinion. In response, Drnovšek dismissed Janša and removed the Social Democratic Party from the ruling coalition. The official charges against the military servicemen involved were later dismissed, but the issue remains a point of controversy.[citation needed] Janša used the parliamentary debate on his dismissal to criticize his former allies, Drnovšek and President Milan Kučan, whom he accused of abusing his informal connections for subversive political actions. Janša's dismissal caused a great stir in the public opinion, including mass demonstrations in his support.[citation needed] In local elections the same year, the Social Democratic Party experienced a significant boost in popularity, becoming the main opposition force, and in the 1996 parliamentary elections Janša's party rose from around 3.5% to more than 16%, becoming the third largest political party in the country.

For a short period between June and November 2000, Janša served as Defence Minister in the short-lived centre-right government of Christian democrat Andrej Bajuk. During this time he introduced chaplains to the armed forces.[citation needed] Excluding this interval, Janša remained the leader of the opposition until 2004.

During his time in opposition, Janša supported the government's efforts for the integration into EU and NATO. Between 2002 and 2004, he re-established cordial relations with now-President Drnovšek: in 2003, Drnovšek headed a round table on Slovenia's future based on Janša's recommendations.[24]

Criticism as extremist

During this time, Janša was frequently accused of political extremism and radical discourse. Janša's former friend and fellow dissident Spomenka Hribar argues that his campaigns seem like conspiracy theories, and emphasize emotion, especially patriotic fervor, over rationality.[25][26] The post-Marxist sociologist Rudi Rizman describes Janša's rhetoric as radical populism, close to demagoguery.[27] The notion of "Udbo-Mafija", a term coined by the architect Edo Ravnikar[28] to denote the illegitimate structural connections between the Post-Communist elites, is particularly prevalent in Janša's thought.[27] Most critics agree that Janša is similar to other European radical right-wing populist leaders.[27] Janša's rhetoric is nationalist and xenophobic, including verbal attacks against foreigners, especially from the other former-Yugoslav states, and "communists".[29] Hribar considers these elements a form of extreme nationalism and chauvinism; to her, his irredentist claims towards Croatia seem obvious neo-fascism.[26]

The sociologist Frane Adam instead explains Janša as the product of culture wars between the old Communist elites and the hitherto-disenfranchised elites of the right wing.[30] The writer Drago Jančar similarly interprets the animosity against Janša as unjustified reactions of a culture unused to conservative political discourse.[31]

Ahead of the 2004 electoral campaign, Janša turned towards moderation, tempering his radical language and attacks against alleged Communists. Still, some critics continued to point out nationalistic rhetoric against immigrants.[32]

2004–2008 first term as prime minister

Janša was prime minister of Slovenia for the first timefrom November 2004 to November 2008. During the term characterized by over-enthusiasm after joining EU, between 2005 and 2008 the Slovenian banks have seen loan-deposit ratio veering out of control, over-borrowing from foreign banks and then over-crediting private sector, leading to its unsustainable growth.

It was also for the first time after 1992 that the president and the prime minister had represented opposing political factions for more than a few months. The relationship between Drnovšek and the government quickly became tense. After the landslide victory of the opposition candidate Danilo Türk in the 2007 presidential election, Janša filed a Motion of Confidence in the government on 15 November 2007, stating that the opposition's criticism was interfering with the government's work during Slovenia's presidency over the European Union.[33] The government won the vote, held on 19 November, with 51 votes supporting it and 33 opposing it.[34] In the speech delivered after the vote, Janša announced, among other, an intensification of the fight against financial criminality and the illegal concentration of capital in the hands of single powerful managers, to whom he referred as tycoons. In the following months, the Slovenian police and public prosecution launched a full-scale investigation against some of the biggest companies in the country, namely against the Laško Brewery Concern.

In the beginning of December 2011, several clips of the recordings of closed sessions of the Government of Slovenia during the term of Janez Janša were published on the video-sharing website YouTube.[35][36]

Allegations were made against Janez Janša that he tried to subordinate Slovenian media.[37] On 1 September 2008, some three weeks before the Slovenian parliamentary elections, allegations were made in Finnish TV in a documentary broadcast by the Finnish national broadcasting company YLE that Janša had received bribes from the Finnish defense company Patria (73.2% of which is the property of the Finnish government) in the so-called Patria case.[38][39][40] Janša rejected all accusations as a media conspiracy concocted by left-wing Slovenian journalists, and demanded YLE to provide evidence or to retract the story.[41] Janša's naming of individual journalists, including some of those behind the 2007 Petition Against Political Pressure on Slovenian Journalists, and the perceived use of diplomatic channels in an attempt to coerce the Finnish government into interfering with YLE editorial policy, drew criticism from media freedom organizations, such as the International Press Institute[42][43] and European branch of International Federation of Journalists whose representative, Aidan White, IFJ general secretary, said "The (Janša's) government is distorting the facts, failing to tell Slovenians the truth and trying to pull the wool over the eyes of the European public about its attitude to media".[44]

2008–2011 in opposition

In the November 2008 election, Janša's party was placed second and he was replaced as prime minister by Borut Pahor, the Social Democrat leader. After the onset of Financial crisis of 2007–2010 and European sovereign-debt crisis, the left-wing coalition that replaced Janša's government in 2008 elections, had to face the consequences of the 2005–2008 over-borrowing; however, all the attempts to implement reforms that would help towards economic recovery were met by student protesters, led by a student who later became a member of Janez Janša's SDS, and by the trade unions. The proposed reforms were postponed on a referendum.

2011 election and aftermath

In December 2011 Janša's party won the second place in the Slovenian parliamentary elections. Since the prime minister-designate of the first-placed party, Positive Slovenia, Zoran Janković failed to secure himself enough votes in the National Assembly,[45] and Danilo Türk, the President of Slovenia, declined to propose Janša as prime minister because Janša had been charged in the Patria bribery case, Janša was proposed as prime minister by the coalition of the parties SDS, SLS, DeSUS, NSi, and the newly formed Gregor Virant's Civic List on 25 January 2012.[46] On 28 January he became prime minister-designate.[47] His cabinet[48] was confirmed on 10 February, and Janša became the new prime minister with a handover from Pahor on the same day.[49][50] On 13 February the President received the new Government and wished them luck. Both parties agreed that good cooperation is crucial for success.[51]

2012–2013: second term as prime minister

During his second term as prime minister, which lasted only one year, Janez Janša responded to the weakening of Slovenian economy during the global economic crisis and European sovereign-debt crisis with opening up old ideological fronts against liberal media, and against public sector – especially educational and cultural sectors, accusing them of being under influence of members of old regime (called Udbomafia and "Uncles from Behind the Scenes" (In Slovene: "strici iz ozadja")[52]) and against everyone who doubted that austerity measures forced upon Slovenia are right ones.[53][54]

Slovenian political elites faced the 2012–2013 Slovenian protests demanding their resignation.[55][56][57][58]

In January 2013, the 2012–2013 Investigation Report on the parliamentary parties' leaders by Commission for the Prevention of Corruption of the Republic of Slovenia revealed that Janez Janša and Zoran Janković systematically and repeatedly violated the law by failing to properly report their assets.[59][59][60][61] It revealed his purchase of one of the real-estate was indirectly co-funded by a construction firm, a major government contractor.[59] It showed that his use of funds in the amount of at least 200.000 EUR, coming from unknown origin, exceeded both his income and savings.[59]

Immediately after the release of the report, Civic List issued an ultimatum to Janša's party to find another party member to serve as a new PM.[62] Since Janša was ignoring the report and his party didn't offer any replacement for him, all three coalition parties and their leaders left the government within weeks and were subjected to ad hominem attacks by Janez Janša who accused the SLS's leader Radovan Žerjav of being "the worst (economics) minister in history of Slovenia", while the leader of the Civic List Gregor Virant has been mocked by Janša as engaging in "virantovanje" (a word game on kurentovanje, a Slovenian carnival festival).[63][64][65] On 27 February 2013, Janša's government fell, following a vote of no confidence over allegations of corruption and an unpopular austerity programme in the midst of the country's recession. Gregor Virant welcomed the outcome of the vote, stating that it will enable Slovenia to move forward, either to form a new government or to call for an early election.[66]

2013: In opposition and court trial

Following the fall of his government, Janša decided not to resume his position as a member of the National Assembly. Instead, he decided to work for his party (SDS), write books, lecture at international institutes and help as a counsellor.[67]

On 5 June 2013, the District Court in Ljubljana ruled that Janša and two others had sought about €2m in commission from a Finnish firm, Patria, in order to help it win a military supply contract in 2006 (Patria case).[68] Janša was sentenced to two years while Tone Krkovič and Ivan Črnkovič, his co-defendants, were each sentenced to 22 months in prison. All three were also fined €37,000 each.[68][69] Janša has denied the accusations, claiming the whole process is politically motivated.[70] The following day, the Minister of Justice, Senko Pličanič, emphasised that the court ruling was not yet binding and therefore Janša was still presumed innocent.[71]

Several hundred supporters had rallied outside the court to protest the ruling, while another group of people welcomed the outcome.[72] In his first response, Janša stated he will fight with all available legal and political means to overturn the ruling at the superior court.[73] He has also drawn parallels to the politically motivated JBTZ trial, where he was sentenced to prison 25 years ago.[73] Members of SDS, NSi and SLS, the opposition parties, condemned the ruling.[72] The coalition mostly abstained from comments. Borut Pahor, the President of Slovenia, stressed that the authority of the court should be respected, regardless of personal opinions.[74] The ruling was welcomed by the members of the Protest movement and Goran Klemenčič of the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption of the Republic of Slovenia, who stated that the fight against corruption in Slovenia must continue.[75]

2014: In prison

After the Constitutional Court of Slovenia with the majority of votes dismissed Janša's appeal due to him not having exhausted every other legal means available to him, on 20 June 2014 Janša started serving his prison term in Dob Prison, the largest Slovene prison. He was escorted there by about 3,000 supporters.[76] The influential German centre-right wing newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung reported the following day that the domestic Slovene and the international law experts recognised large violations of Janša's rights in the court case.[77] The case is to be reviewed by the Supreme Court, but this does not postpone the execution of the sentence that started just three weeks before the parliamentary election. Former constitutional judges criticised the decision of the Constitutional Court for being based on formalities instead of on the content, and commented that a large legal inconsistency in the process was discovered only in front of the Constitutional Court and that it will prevent the Supreme Court from not overturning the judgement.[78] On 12 December 2014 Janša was temporarily released from the prison pending the review of the case by the Constitutional Court.[79] The conviction was unanimously overturned by the Constitutional Court on 23 April 2015.[9]

2018: Election

In the early election on 3 June 2018, Janez Janša was re-elected as a deputy. He was elected in the electoral district of Grosuplje and received 7,020 votes or 39.3%, the largest share of all candidates in the country. The Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) won the election by receiving 24.92% of votes and gaining 25 seats out of 90 in the National Assembly. [80]

2020: Third term as prime minister

Following the resignation of Marjan Šarec as prime minister, Janša was elected as prime minister-designate on 3 March 2020, to form the 14th Government of Slovenia.[10] He was sworn in on 13 March 2020.[81][82]

Accusations of plagiarism

The largest and most notable Roman Catholic newspaper Družina and Janša have both claimed that the very few individuals who managed to survive the Kočevski Rog massacre included Janša's father, although the story of the actual survivor France Dejak, which was told in 1989 for the first time in Mladina,[83] was re-told in details as if it has been experienced by Janša's father.

In 2008, it was reported by the newspaper Mladina that Janez Janša copied a speech by Tony Blair, the prime minister of the United Kingdom. It was used in 2006 for the ceremony on the 15th anniversary of the Slovenian declaration of independence. His office responded with the claim that it was not copied but similar to Blair's speech, and that this were only a few phrases often used for such occasions. A few of these sentences were proclaimed the Spade of the Year by the newspaper Večer in 2006; the award is given annually to the best publicly expressed thought in Slovenia.[84]

Personal life

Janša is an active mountaineer, golfer, footballer, skier and snowboarder.[85]

Janša had a long-term relationship with Silva Predalič, who bore him two children, a son and a daughter.[85][86]

Since July 2009, Janša has been married to Urška Bačovnik (MD) from Velenje. The two had been dating since 2006.[87] In August 2011, their son Črtomir was born.[88] Their second son, Jakob, was born in August 2013.[89]

Books

Janša has published several books, the two of which are Premiki ("Manoeuvres", published in 1992 and subsequently translated into English under the title "The Making of the Slovenian State") and Okopi ("Barricades", 1994), in which he exposes his personal views on the problems of Slovenia's transition from Communism to a parliamentary democracy. In both books, but particularly in Okopi, Janša criticized the then president of Slovenia Milan Kučan of interfering in daily politics using the informal influence he had gained as the last chairman of the Communist Party of Slovenia. He published second edition of the same book: Dvajset let pozneje Okopi with some additional documents and personal views.

- Podružbljanje varnosti in obrambe ('The Socialization of Security and Defence', editor); Ljubljana: Republiška konferenca ZSMS, 1984.

- Stane Kavčič, Dnevnik in spomini ('The Memoirs of Stane Kavčič', co-edited with Igor Bavčar); Ljubljana: ČKZ, 1988.

- Na svoji strani ('On One's Own Side', collection of articles); Ljubljana: ČKZ, 1988.

- Premiki: nastajanje in obramba slovenske države 1988–1992; Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1992. English translation: The Making of the Slovenian State, 1988–1992: the Collapse of Yugoslavia; Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1994.

- Okopi: pot slovenske države 1991–1994 ('Trenches: the Evolution of the Slovenian State, 1991–1994'); Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1994.

- Sedem let pozneje ('Seven Years Later'). Ljubljana: Založba Karantanija, 1994.

- Osem let pozneje ('Eight Years Later', co-authored with Ivan Borštner and David Tasić); Ljubljana: Založba Karantanija, 1995.

- Dvajset let pozneje, Okopi II ('Twenty Years Later, Trenches II'). Ljubljana: Založba Mladinska knjiga, 2014.

References

- ^ "Slovenski pravopis 2001: Ivan". "Slovenski pravopis 2001: Janša".

- ^ "Janša: P.S. Janez ni moj vzdevek" [Janša: P.S.: Janez is not my Nickname]. 24ur.si (in Slovenian). 28 September 2010.

- ^ "Slovenski pravopis 2001: Janez". "Slovenski pravopis 2001: Janša".

- ^ "Parliament Endorses Janša for PM-Elect (roundup)". Slovenian Press Agency. 28 January 2012.

- ^ "Sklep o izvolitvi predsednika Vlade Republike Slovenije". Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia. 28 January 2011.

- ^ "Slovenia parliament ousts PM Jansa". 28 February 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Janša to "Fight to the End", Says Conviction Political". The Slovenia Times. 5 June 2013.

- ^ "Slovenian court confirms jail sentence for ex-PM Jansa". Reuters. 28 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Constitutional court overturned the convictions in the Patria case". MMC RTV Slovenia. 23 April 2015.

- ^ a b https://www.rtvslo.si/radiosi/news/jansa-to-head-slovenia-s-next-government/516102

- ^ Janez Janša, Okopi (Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1994)

- ^ "Slovenska pomlad – Osebe". Slovenskapomlad.si. 27 July 1988. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Vlasta Jalušič and Lev Kreft, eds., Vojna in mir: refleksije dvajsetih let (Ljubljana: Mirovni inštitut, 2009)

- ^ a b "Jabolko in politika". Jabolko.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Božo Repe and Jože Prinčič, Pred časom: portret Staneta Kavčiča (Ljubljana: Modrijan 2009), 48–49

- ^ a b Božo Repe and Jože Prinčič, Pred časom: portret Staneta Kavčiča (Ljubljana: Modrijan 2009), 49

- ^ a b "Slovenska pomlad – Dogodki". Slovenskapomlad.si. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Janez Janša, Okopi (Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1995).

- ^ "Dnevnik – Intervju". Mladina.si. 27 July 2006. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Članki – N01". Users.volja.net. Archived from the original on 14 March 2004. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Slavoj Žižek, Druga smrt Josipa Broza Tita (Ljubljana: DZS, 1989).

- ^ Tine Hribar, Slovenci kot nacija: srečanja s sodobniki (Ljubljana: Enotnost, 1995), 261

- ^ "Drnovšek podpira Janševo pobudo". 24ur.com. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Spoemnka Hribar, Svet kot zarota (Ljubljana: Enotnost, 1996)

- ^ a b Hribar, Spomenka, in: Mladina, 4 July 1995, p. 17

- ^ a b c Rizman, Rudolf M. (1999), "Radical Right Politics in Slovenia", The radical right in Central and Eastern Europe since 1989, Penn State Press, pp. 159–162, retrieved 14 November

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Edo Ravnikar, Udbomafija: priročnik za razumevanje tranzicije (Ljubljana: Slon – Embea, 1995)

- ^ Hall, Ian; Perrault, Magali (3 April 2000), "The Re-Austrianisation of Central Europe?", Central Europe Review, 2 (13), retrieved 14 November 2011

- ^ Frane Adam, Ambivalentnost in neznosna lahkost tranzicije in Niko Grafenauer, France Bučar et al., eds., Sproščena Slovenija – Obračun za Prihodnost (Ljubljana: Nova revija, 1999), 99–113

- ^ Drago Jančar, Slovenske marginalije, Niko Grafenauer, France Bučar et al., eds., Sproščena Slovenija – Obračun za Prihodnost (Ljubljana: Nova revija, 1999), 159–185

- ^ Rizman, Rudolf M. (2006), Uncertain path: Democratic transition and consolidation in Slovenia, Texas A&M University Press, pp. 74–75, retrieved 14 November 2011

- ^ "Slovenian PM seeks confidence vote after opposition candidate became president", Associated Press (International Herald Tribune), 16 November 2007.

- ^ "A Slovenian government crisis averted"[permanent dead link], Courrier International, 21 November 2007.

- ^ "Afera Youtube: Pahor je objektivno odgovoren in bi moral še enkrat odstopiti" [YouTube Scandal: Pahor is Objectively Responsible and Should Step Down] (in Slovenian). MMC RTV Slovenia. 9 November 2011.

- ^ "Tapes of Govt Sessions Uploaded to Youtube". Slovenian Press Agency. 9 November 2011.

- ^ "www.ednevnik.si". Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ YLE Claims Stir Political Storm In Slovenia, YLE

- ^ "Slovenia Delivers Note to Finland Over TV Programme Accusations". Yle.fi. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Mot: The Truth about Patria Archived 3 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Janša: Hude obtožbe brez dokazov" (in Slovenian). MMC RTV SLO. 3 September 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ IPI Concerned at Slovenian Government's Use of Diplomatic Pressure in Response to Finnish Media's Handling of Patria Bribery Scandal

- ^ www.freemedia.at Archived 24 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Journalists Say Slovenia Fails Test of Leadership in European Union over Press Freedom Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ), 11 January 2008

- ^ "Türk: Obžalujem neizvolitev. Zoran Janković ostaja resen kandidat" [Türk: I Regret the Non-Election. Zoran Janković Remains a Serious Candidate] (in Slovenian). MMC RTV Slovenia. 11 January 2012.

- ^ "Foto: Janša: Za nami stoji 600.000 volivcev" [Photo: Janša: 600,000 Voters Stand Behind Us]. 24ur.com (in Slovenian).

- ^ "Parliament Endorses Janša". Slovenia Times. 28 January 2012.

- ^ "Ministers in Slovenia's Tenth Cabinet (bio)". Slovenian Press Agency. 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Janša Formally Takes Over from Pahor". Slovenian Press Agency. 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Slovenia gets new cabinet, two months after elections". Europe Online ate=10 February 2012.

- ^ "President Receives New Govt, Highlights Cooperation". Slovenian Press Agency. 13 February 2012. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012.

- ^ Uncles from Behind the Scenes (In Slovene: "Strici iz ozadja"), Dnevnik, 10. November 2012

- ^ IMF calls time on austerity – but can Greece survive?, BBC News, 11 October 2012

- ^ A Symposium of Law Experts. Political arbitrariness has gone wild. (In Slovene: "Posvet pravnikov. Samovolja politikov presega vse meje"), Dnevnik, 18 January 2013.

- ^ "Vstala bo država: Protesti v Ljubljani, Mariboru, Ajdovščini, na Ptuju in v Novi Gorici". Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Vseslovenska vstaja za boljše življenje". Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "2. vseslovenska ljudska vstaja:

". Retrieved 4 March 2018. - ^ "Na tretji vseslovenski vstaji 20.000 ljudi: »Čas je, da dobimo nazaj našo državo!«". Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Official News Archived 8 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine on the Commission's website, 10 January 2013, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

- ^ Most powerful politicians do not know where they got the money (In Slovene: "Najmočnejša politika ne vesta odkod jima denar"), Delo, 9 January 2013

- ^ Žerdin, A. (2013)There is no room for an unexplained sources of money in the public servants' budgets (In Slovene: "V bilancah funkcionarjev ni prostora za gotovino neznanega izvora"), Delo

- ^ Virant's party responded to Janša's ultimatum with their ultimatum (In Slovene: "Virantovi na Janšev ultimat z ultimatom"), Delo, 12 January 2013

- ^ – Janša to Žerjav: The worst minister of the economy in the history of Slovenia has left the government, MMC RTV Slovenija, 25 February 2013

- ^ Section of Virant: Virantovanje resembles kurentovanje, MMC RTV Slovenija, 14 February 2013

- ^ Desus has left the government, Delo, 12 January 2013

- ^ "Znotraj DZ-ja jasna podpora, zunaj njega odzivi mešani". Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Janez Janša bo pisal in predaval". Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Ex-Slovenian PM Jansa convicted". 5 June 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Janša, Krkovič in Črnkovič krivi :: Prvi interaktivni multimedijski portal, MMC RTV Slovenija

- ^ "Ex-PM Janez Jansa sentenced to 2 years in prison for corruption in Patria arms deal case". 5 June 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Pličanič: Z oceno političnega dometa obsodbe Janše treba počakati do pravnomočnosti sodbe" [Pličanič: It Must be Waited with the Evaluation of the Political Importance of the Conviction of Janša Until the Ruling Becomes Binding] (in Slovenian). Siol.net. 6 June 2013.

- ^ a b "Odzivi: Sodba je fiasko, blamaža, zgodovinski dogodek". Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Janez Janša: Sodba je sramota za Slovenijo, borili se bomo do konca". Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Pahor: Odločitve ustanov pravne države moramo spoštovati". Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "KPK: Sodba v zadevi Patria ne more biti zadnja in edina". Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Janša Arrives at Dob Prison (adds)". Slovene Press Agency. 20 June 2014.

- ^ "FAZ: V postopku proti Janši so bila kršena načela pravne države" [FAZ: The Principles of a Legal State Were Violated in the Process Against Janša]. Planet Siol.net (in Slovenian). 21 June 2014.

- ^ "Odzivi: Nekdanji ustavni sodniki kritični do odločitve sodišča o Janševi pritožbi" [Responses: The Former Constitutional Judges Critical to the Decision of the Court about Janša's Appeal] (in Slovenian).

- ^ "Ex-Slovenia PM temporarily released from prison". AP. 12 December 2014.

- ^ https://dvk-rs.si/arhivi/dz2018/#/prva

- ^ https://www.reuters.com/article/us-slovenia-government/slovenian-parliament-confirms-center-right-cabinet-of-pm-jansa-idUSKBN210360

- ^ https://apnews.com/fa066431d630bbd78087a73be44db9d7

- ^ Bogomir Štefanič Jr. (2009). [1] Totalitarna kultura smrti in zgodba družine Janša. Družina. 25 March 2009. Accessed: 2012-04-01. (Archived by WebCite® at https://www.webcitation.org/66boYDLp5?url=http://www.druzina.si/icd/spletnastran.nsf/all/9C736E1DB0201F02C12575860035236D?OpenDocument )

- ^ "Janša prepisal govor od Blaira" [Janša Copied His Speech from Blair]. Delo.si (in Slovenian and English). 21 June 2008.

- ^ a b "Curriculum Vitae". Office of the Prime Minister. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ "Janša poročen s Silvio" (in Slovenian). Vest.si. 27 October 2007. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ "Janez in Urška sta uradno zaročena" (in Slovenian). MMC RTV SLO. 9 January 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ "Rodil se je Črtomir Janša". Slovenskenovice.si. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Janša ima sina Jakoba" [Janša Has the Son Jakob] (in Slovenian). Slovenskenovice.si. 13 August 2008.

External links

- Use dmy dates from June 2013

- 1958 births

- Defence ministers of Slovenia

- Living people

- Slovenian politicians convicted of crimes

- People from Grosuplje

- Presidents of the European Council

- Prime Ministers of Slovenia

- Slovenian Democratic Party politicians

- Slovenian Democratic Union politicians

- Slovenian non-fiction writers

- Slovenian Roman Catholics

- Slovenian Spring

- University of Ljubljana alumni

- Heads of regimes who were later imprisoned