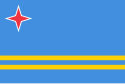

Aruba

Aruba (/əˈruːbə/ ə-ROO-bə, Dutch: [aːˈrubaː, -ryb-] , Papiamento: [aˈruba]) is an island and a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the southern Caribbean Sea, located about 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) west of the main part of the Lesser Antilles and 29 kilometres (18 mi)[5] north of the coast of Venezuela. It measures 32 kilometres (20 mi) long from its northwestern to its southeastern end and 10 kilometres (6 mi) across at its widest point.[5] Together with Bonaire and Curaçao, Aruba forms a group referred to as the ABC islands. Collectively, Aruba and the other Dutch islands in the Caribbean are often called the Dutch Caribbean.

Aruba is one of the four countries that form the Kingdom of the Netherlands, along with the Netherlands, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten; the citizens of these countries are all Dutch nationals.[6] Aruba has no administrative subdivisions, but, for census purposes, is divided into eight regions. Its capital is Oranjestad.[6][5]

Unlike much of the Caribbean region, Aruba has a dry climate and an arid or desert, cactus-strewn landscape.[5][6] This climate has helped tourism as visitors to the island can reliably expect warm, sunny clear skies year-round. It has a land area of 179 km2 (69.1 sq mi) and is densely populated, with a total of 101,484 inhabitants at the 2010 Census. Current estimates of the population place it at 116,600 (July 2018 est.)[6] It lies outside Hurricane Alley.[6]

Etymology

There are different theories as to the origin of the name Aruba:[6][7]

- From the Spanish Oro hubo which means "there was gold"[6]

- From the Island Carib word Oruba which means "well-placed"[6]

- From the Island Carib words Ora ("shell") and Oubao ("island")[8]

History

Pre-colonial era

There has been a human presence on Aruba from as early as circa 2000 BC.[9] The first identifiable group are the Arawak Caquetío Amerindians who migrated from South America about 1000 AD.[9][10] Archaeological evidence suggests continuing links between these native Arubans and Amerindian peoples of mainland South America.[7]

Arrival of Europeans and Spanish period

The first Europeans to visit Aruba were Amerigo Vespucci and Alonso de Ojeda in 1499, who claimed the island for Spain.[9] Both men described Aruba as an "island of giants", remarking on the comparatively large stature of the native Caquetíos.[7] Vespucci returned to Spain with stocks of cotton and brazilwood from the island and described houses built into the ocean.[citation needed] Vespucci and Ojeda's tales spurred interest in Aruba, and the Spanish began colonising the island.[11][12] Alonso de Ojeda was appointed the island's first governor in 1508. From 1513 the Spanish began enslaving the Caquetíos, sending many to a life of forced labour in the mines of Hispaniola.[7][9] The island's low rainfall and arid landscape meant that it was not considered profitable for a slave-based plantation system and the type of large-scale slavery so common on other Caribbean islands never became established on Aruba.[13]

Early Dutch period

The Netherlands seized Aruba from Spain in 1636 in the course of the Thirty Years' War.[5][9] Peter Stuyvesant, later appointed to New Amsterdam (New York), was the first Dutch governor. Those Arawak who had survived the depredations of the Spanish were allowed to farm and graze livestock, with the Dutch using the island as a source of meat for their other possessions in the Caribbean.[7][9] Aruba's proximity to South America resulted in interactions with the cultures of the coastal areas; for example, architectural similarities can be seen between the 19th-century parts of Oranjestad and the nearby Venezuelan city of Coro in Falcón State.[citation needed] Historically, Dutch was not widely spoken on the island outside of colonial administration; its use increased in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[14] Students on Curaçao, Aruba, and Bonaire were taught predominantly in Spanish until the late 18th century.[15]

During the Napoleonic Wars the British Empire took control of the island, occupying it between 1806 and 1816, before handing it back to the Dutch as per the terms of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814.[7][5][16][9] Aruba subsequently became part of the Colony of Curaçao and Dependencies along with Bonaire. During the 19th century an economy based on gold mining, phosphate production and aloe vera plantations developed, however the island remained a relatively poor backwater.[7]

20th and 21st centuries

The first oil refinery in Aruba was built in 1928 by Royal Dutch Shell. The facility was built just to the west of the capital city Oranjestad and was commonly called the Eagle. Immediately following this, another refinery was built by Lago Oil and Transport Company in an area now known as San Nicolas on the east end of Aruba. These refineries processed crude oil from the vast Venezuelan oil fields, bringing greater prosperity to the island.[17] The refinery on Aruba grew to become one of the largest in the world.[7]

During World War II, the Netherlands was occupied by Nazi Germany. In 1940, the oil facilities in Aruba came under the administration of the Dutch government-in-exile in London, causing them to be attacked by the German navy in 1942.[7][18]

In August 1947, Aruba presented its first Staatsreglement (constitution) for Aruba's status aparte as an autonomous state within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, prompted by the efforts of Henny Eman, a noted Aruban politician. By 1954, the Charter of the Kingdom of the Netherlands was established, providing a framework for relations between Aruba and the rest of the Kingdom.[19] This created the Netherlands Antilles, which united all of the Dutch colonies in the Caribbean into one administrative structure.[20] Many Arubans were unhappy at the arrangement, however, as the new polity was perceived as being dominated by Curaçao.[5]

In 1972, at a conference in Dutch Guiana, Betico Croes, a politician from Aruba, proposed the creation of a Dutch Commonwealth of four states: Aruba, the Netherlands, Suriname, and the Netherlands Antilles, each to have its own nationality. Backed by his newly-created party (the Movimiento Electoral di Pueblo), Croes sought greater autonomy for Aruba, with the long-term goal of independence, adopting the trappings of an independent state in 1976 with the creation of a flag and national anthem.[7] In March 1977, a referendum was held with the support of the United Nations; 82% of the participants voted for complete independence from the Netherlands.[7][21] Tensions mounted as Croes stepped up the pressure on the Dutch government by organising a general strike in 1977.[7] Croes later met with Dutch Prime Minister Joop den Uyl, with the two sides agreeing to assign the Institute of Social Studies in The Hague to prepare a study for independence, entitled Aruba en Onafhankelijkheid, achtergronden, modaliteiten, en mogelijkheden; een rapport in eerste aanleg (Aruba and independence, backgrounds, modalities, and opportunities; a preliminary report) (1978).[7]

In March 1983, Aruba reached an official agreement within the Kingdom for its independence, to be developed in a series of steps as the Crown granted increasing autonomy. In August 1985, Aruba drafted a constitution that was unanimously approved. On 1 January 1986, after elections were held for its first parliament, Aruba seceded from the Netherlands Antilles, officially becoming a country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with full independence planned for 1996.[7] However, Croes was seriously injured in a traffic accident in 1985, slipping into a coma; he died in 1986, never seeing the enaction of status aparte for Aruba for which he had worked over many years.[7] After his death in 1986, Croes was proclaimed Libertador di Aruba.[7] Thus Henny Eman of the Aruban People's Party (AVP) became the first Prime Minister of Aruba. Meanwhile, Aruba's oil refinery shut, negatively impacting the economy. As a result, Aruba pushed for a dramatic increase in tourism, with this sector growing to become the island's largest industry.[7]

At a convention in The Hague in 1990, at the request of Aruba's Prime Minister Nelson Oduber, the governments of Aruba, the Netherlands, and the Netherlands Antilles postponed indefinitely Aruba's transition to full independence.[7] The article scheduling Aruba's complete independence was rescinded in 1995, although the process could be revived after another referendum.

Geography

Aruba is a generally flat, riverless island in the Leeward Antilles island arc of the Lesser Antilles in the southern part of the Caribbean. It lies 77 km (48 mi) west of Curaçao and 29 km (18 mi) north of Venezuela's Paraguaná Peninsula.[5] Aruba has white sandy beaches on the western and southern coasts of the island, relatively sheltered from fierce ocean currents.[5][22] This is where the bulk of the population live and where most tourist development has occurred.[22][6] The northern and eastern coasts, lacking this protection, are considerably more battered by the sea and have been left largely untouched.

The hinterland of the island features some rolling hills, such as Hooiberg at 165 meters (541 ft) and Mount Jamanota, the highest on the island at 188 meters (617 ft) above sea level.[5][6] Oranjestad, the capital, is located at 12°31′01″N 70°02′04″W / 12.51694°N 70.03444°W.

The Natural Bridge was a large, naturally formed limestone bridge on the island's north shore. It was a popular tourist destination until its collapse in 2005.

Cities and towns

The island, with a population of about 116,600 people (July 2018 est.)[6] does not have major cities. It is divided into six districts.[23] Most of the island's population resides in or around the two major city-like districts of Oranjestad (the capital) and San Nicolaas. Oranjestad and San Nicolaas are both divided into two districts for census purposes only.[24] The districts are as follows:

Fauna

The isolation of Aruba from the mainland of South America has fostered the evolution of multiple endemic animals. The island provides a habitat for the endemic Aruban Whiptail and Aruba Rattlesnake, as well as an endemic subspecies of Burrowing Owl and Brown-throated Parakeet.

Flora

The flora of Aruba differs from the typical tropical island vegetation. Xeric scrublands are common, with various forms of cacti, thorny shrubs, and evergreens.[5] Aloe vera is also present, its economic importance earning it a place on the Coat of Arms of Aruba.

Cacti like Melocactus and Opuntia are represented on Aruba by species like Opuntia stricta. Trees like Caesalpina coriaria and Vachellia tortuosa are drought tolerant.

Climate

By the Köppen climate classification, Aruba has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh).[25] Mean monthly temperature in Oranjestad varies little from 26.7 °C (80.1 °F) to 29.2 °C (84.6 °F), moderated by constant trade winds from the Atlantic Ocean, which come from the north-east. Yearly rainfall barely exceeds 470 millimetres or 18.5 inches in Oranjestad, although it is extremely variable[26] and can range from as little as 150 millimetres or 5.91 inches during strong El Niño years (e.g. 1911/1912, 1930/1931, 1982/1983, 1997/1998) to over 1,000 millimetres or 39.37 inches in La Niña years like 1933/1934, 1970/1971 or 1988/1989.

| Climate data for Oranjestad, Aruba (1981–2010, extremes 1951–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.5 (90.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.9 (93.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.9 (94.8) |

35.2 (95.4) |

35.3 (95.5) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.5 (97.7) |

35.4 (95.7) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.8 (94.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.0 (86.0) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.4 (86.7) |

31.5 (88.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.7 (80.1) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.5 (76.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 21.3 (70.3) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.5 (68.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 39.3 (1.55) |

20.6 (0.81) |

8.7 (0.34) |

11.6 (0.46) |

16.3 (0.64) |

18.7 (0.74) |

31.7 (1.25) |

25.8 (1.02) |

45.5 (1.79) |

77.8 (3.06) |

94.0 (3.70) |

81.8 (3.22) |

471.8 (18.58) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.4 | 5.0 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 7.4 | 10.6 | 11.4 | 64.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77.5 | 76.1 | 75.7 | 77.1 | 77.9 | 77.4 | 77.8 | 76.2 | 76.8 | 78.6 | 79.1 | 78.4 | 77.4 |

| Source: DEPARTAMENTO METEOROLOGICO ARUBA,[27] (extremes)[25] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

In terms of country of birth, the population is estimated to be 66% Aruban, 9.1% Colombian, 4.3% Dutch, 4.1% Dominican, 3.2% Venezuelan, 2.2% Curaçaoan, 1.5% Haitian, 1.2% Surinamese, 1.1% Peruvian, 1.1% Chinese, 6.2% other.[2]

In terms of ethnic composition, the population is estimated to be 75% multiracial, 15% black and 10% other ethnicities.[citation needed] Arawak heritage is stronger on Aruba than on most Caribbean islands; although no full-blooded Aboriginals remain, the features of the islanders clearly indicate their genetic Arawak heritage.[citation needed] Most of the population is descended from Caquetio Indians and Dutch settlers, and to a lesser extent the various other groups that have settled on the island over time, such as various African peoples, Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, and Sephardic Jews.

Recently, there has been substantial immigration to the island from neighbouring South American and Caribbean nations, attracted by the higher paid jobs. In 2007, new immigration laws were introduced to help control the growth of the population by restricting foreign workers to a maximum of three years residency on the island.[citation needed] Most notable are those from Venezuela, which lies just 29 km (18 mi) to the south.

Language

The official languages are Dutch and Papiamento. However, whilst Dutch is the sole language for all administration and legal matters,[28] Papiamento is the predominant language used on Aruba. It is a creole language, spoken on Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao, that incorporates words from Portuguese, various West African languages, Dutch, and Spanish.[5] English is also spoken, its usage having grown due to tourism.[5][6] Other common languages spoken, based on the size of their community, are Portuguese, German, Spanish, and French.

In recent years, the government of Aruba has shown an increased interest in acknowledging the cultural and historical importance of Papiamento. Although spoken Papiamento is fairly similar among the several Papiamento-speaking islands, there is a big difference in written Papiamento.[citation needed] The orthography differs per island, with Aruba using etymological spelling, and Curaçao and Bonaire a phonetic spelling. Some are more oriented towards Portuguese and use the equivalent spelling (e.g. "y" instead of "j"), where others are more oriented towards Dutch.

The book Buccaneers of America, first published in 1678, states through eyewitness account that the natives on Aruba spoke Spanish already.[29]Spanish became an important language in the 18th century due to the close economic ties with Spanish colonies in what are now Venezuela and Colombia.[30] Venezuelan TV networks are received on the island, and Aruba also has significant Venezuelan and Colombian communities.[citation needed] Around 12.6% of the population today speaks Spanish.[31] Use of English dates to the early 19th century, when the British took Curaçao, Aruba, and Bonaire. When Dutch rule resumed in 1815, officials already noted wide use of the language.[14]

Aruba has four newspapers published in Papiamento: Diario, Bon Dia, Solo di Pueblo, and Awe Mainta, and three in English: Aruba Daily, Aruba Today, and The News.Amigoe is a newspaper published in Dutch. Aruba also has 18 radio stations (two AM and 16 FM) and two local television stations (Telearuba and Channel 22).[32]

Religion

Roman Catholicism is the dominant religion, practiced by about 45% of the population.[6] Various Protestant denominations are also present on the island.[6][5]

Regions

For census purposes, Aruba is divided into eight regions, which have no administrative functions:

| Name | Area (km²) | Population 1991 Census |

Population 2000 Census |

Population 2010 Census |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noord / Tanki Leendert | 34.62 | 10,056 | 16,944 | 21,495 |

| Oranjestad West | 9.29 | 8,779 | 12,131 | 13,976 |

| Oranjestad Oost | 12.88 | 11,266 | 14,224 | 14,318 |

| Paradera | 20.49 | 6,189 | 9,037 | 12,024 |

| San Nicolas Noord | 23.19 | 8,206 | 10,118 | 10,433 |

| San Nicolas Zuid | 9.64 | 5,304 | 5,730 | 4,850 |

| Santa Cruz | 41.04 | 9,587 | 12,326 | 12,870 |

| Savaneta | 27.76 | 7,273 | 9,996 | 11,518 |

| Total Aruba | 178.91 | 66,687 | 90,506 | 101,484 |

Government

Along with the Netherlands, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten, Aruba is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with internal autonomy.[6] Matters such as foreign affairs and defense are handled by the Netherlands.[6] Aruba's politics take place within a framework of a 21-member Staten (Parliament) and an eight-member Cabinet; the Staten's 21 members are elected by direct, popular vote to serve a four-year term.[5][33] The governor of Aruba is appointed for a six-year term by the monarch, and the prime minister and deputy prime minister are indirectly elected by the Staten for four-year terms.[6]

Aruba was formerly a part of the (now-defunct) Netherlands Antilles; however, it separated from that entity in 1986, gaining its own constitution.[6][5]

Aruba is designated as a member of the Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT) and is thus officially not a part of the European Union, though Aruba can and does receive support from the European Development Fund.[34][35]

Politics

The Aruban legal system is based on the Dutch model. In Aruba, legal jurisdiction lies with the Gerecht in Eerste Aanleg (Court of First Instance) on Aruba, the Gemeenschappelijk Hof van Justitie van Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten, en van Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba (Joint Court of Justice of Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten, and of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba) and the Hoge Raad der Nederlanden (Supreme Court of Justice of the Netherlands).[36] The Korps Politie Aruba (Aruba Police Force) is the island's law enforcement agency and operates district precincts in Oranjestad, Noord, San Nicolaas, and Santa Cruz, where it is headquartered.[37]

Deficit spending has been a staple in Aruba's history, and modestly high inflation has been present as well. By 2006, the government's debt had grown to 1.883 billion Aruban florins.[38] In 2006, the Aruban government changed several tax laws to reduce the deficit. Direct taxes have been converted to indirect taxes as proposed by the IMF.[39]

Foreign relations

Like Bonaire and a few other Dutch dependencies, Aruba maintains economic and cultural relations with European Union and United States of America.[citation needed]

Military

Defence on Aruba is the responsibility of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.[6] The Dutch Armed Forces that protect the island include the Navy, Marine Corps, and the Coastguard including a platoon sized national guard.

All forces are stationed at Marines base in Savaneta. Furthermore, in 1999, the U.S. Department of Defense established a Forward Operating Location (FOL) at the airport.[40]

Education

Aruba's educational system is patterned after the Dutch system of education.[41] The government of Aruba finances the public national education system.[42]

Schools are a mixture of public and private, including the International School of Aruba,[43] the Schakel College[44] and mostly the Colegio Arubano.

There are two medical schools, Aureus University School of Medicine and Xavier University School of Medicine,[45][46] as well as its own national university, the University of Aruba.

Economy

The island's economy is dominated by four main industries: tourism, aloe export, petroleum refining, and offshore banking.[6][5] Aruba has one of the highest standards of living in the Caribbean region. The GDP per capita (PPP) for Aruba was estimated to be $37,500 in 2017.[47] Its main trading partners are Colombia, the United States, Venezuela, and the Netherlands.

The agriculture and manufacturing sectors are fairly minimal. Gold mining was formerly important in the 19th century.[5] Aloe was introduced to Aruba in 1840 but did not become a big export until 1890. Cornelius Eman founded Aruba Aloe Balm, and over time the industry became very important to the economy. At one point, two-thirds of the island was covered in Aloe Vera fields, and Aruba become the largest exporter of aloe in the world. The industry continues today, though on a smaller scale.

Access to biocapacity in Aruba is much lower than world average. In 2016, Aruba had 0.57 global hectares [48] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much less than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[49] In 2016 Aruba used 6.5 global hectares of biocapacity per person - their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use almost 12 times the biocapacity that Aruba contains. As a result, Aruba is running a biocapacity deficit.[48]

The official exchange rate of the Aruban florin is pegged to the US dollar at 1.79 florins to US$1.[5][50][51] Because of this fact, and due to a large number of American tourists, many businesses operate using US dollars instead of florins, especially in the hotel and resort districts.[citation needed]

Tourism

About three-quarters of the Aruban gross national product is earned through tourism and related activities.[52] Most tourists are from North America, with a market-share of 73.3%, followed by Latin America with 15.2% and Europe with 8.3%.[53]

For passengers whose destination is the United States, the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS), U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has a full pre-clearance facility in Aruba which has been in effect since 1 February 2001 with the expansion of Queen Beatrix Airport.[citation needed] Since 2008, Aruba has been the only island to have this service for private flights.[54]

Culture

Aruba has a varied culture. According to the Bureau Burgelijke Stand en Bevolkingsregister (BBSB), in 2005 there were ninety-two different nationalities living on the island.[55] Dutch influence can still be seen, as in the celebration of "Sinterklaas" on 5 and 6 December and other national holidays like 27 April, when in Aruba and the rest of the Kingdom of the Netherlands the King's birthday or "Dia di Rey" (Koningsdag) is celebrated.[citation needed]

On 18 March, Aruba celebrates its National Day. Christmas and New Year's Eve are celebrated with the typical music and songs for gaitas for Christmas and the Dande[clarification needed] for New Year, and ayaca, ponche crema, ham, and other typical foods and drinks. On 25 January, Betico Croes' birthday is celebrated. Dia di San Juan is celebrated on 24 June. Besides Christmas, the religious holy days of the Feast of the Ascension and Good Friday are also holidays on the island.

The festival of Carnaval is also an important one in Aruba, as it is in many Caribbean and Latin American countries. Its celebration in Aruba started in the 1950s, influenced by the inhabitants from Venezuela and the nearby islands (Curaçao, St. Vincent, Trinidad, Barbados, St. Maarten, and Anguilla) who came to work for the oil refinery.[citation needed] Over the years, the Carnival Celebration has changed and now starts from the beginning of January until the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday, with a large parade on the last Sunday of the festivities (the Sunday before Ash Wednesday).[citation needed]

Tourism from the United States has recently increased the visibility of American culture on the island, with such celebrations as Halloween in October and Thanksgiving Day in November.[citation needed]

Infrastructure

Aruba's Queen Beatrix International Airport is located near Oranjestad.

Aruba has two ports, Barcadera and Playa, which are located in Oranjestad and Barcadera. The Port of Playa services all the cruise-ship lines, including Royal Caribbean, Carnival Cruise Lines, NCL, Holland America Line, Disney Cruise Line and others. Nearly one million tourists enter this port per year. Aruba Ports Authority, owned and operated by the Aruban government, runs these seaports.

Arubus is a government-owned bus company. Its buses operate from 3:30 a.m. until 12:30 a.m., 365 days a year. Small private vans also provide transportation services in certain areas such Hotel Area, San Nicolaas, Santa Cruz and Noord.

A street car service runs on rails on the Mainstreet.[56]

Utilities

Water-en Energiebedrijf Aruba, N.V. (W.E.B.) produces potable industrial water at the world's third largest desalination plant.[57] Average daily consumption in Aruba is about 37,000 long tons (38,000 t).[58] N.V. Elmar is the sole provider of electricity on the island of Aruba.

Communications

There are two telecommunications providers: Setar, a government-based company and Digicel, which is privately owned. Setar is the provider of services such as internet, video conferencing, GSM wireless technology and land lines.[59] Digicel is Setar's competitor in wireless technology using the GSM platform.[60]

Places of interest

- Beaches

Notable people

- Dave Benton, Aruban-Estonian musician

- Alfonso Boekhoudt, 4th Governor of Aruba

- Xander Bogaerts, MLB shortstop for the Boston Red Sox

- Betico Croes, political activist

- Henny Eman, 1st Prime Minister of Aruba

- Mike Eman, 3rd Prime Minister of Aruba

- Bobby Farrell, musician

- Frans Figaroa, Lieutenant Governor of Aruba 1979-1982

- Henry Habibe, poet

- Andrew Holleran, novelist

- Olindo Koolman, 2nd Governor of Aruba

- Jossy Mansur, editor of the Papiamento language newspaper, Diario

- Diederick Charles Mathew, politician

- Nelson Oduber, 2nd Prime Minister of Aruba

- Sidney Ponson, MLB pitcher for the Baltimore Orioles, San Francisco Giants, St. Louis Cardinals, New York Yankees, Minnesota Twins, Texas Rangers and Kansas City Royals

- Fredis Refunjol, 3rd Governor of Aruba

- Julia Renfro, newspaper editor and photographer

- Jeannette Richardson-Baars, Director of the Police Academy of Aruba

- Felipe Tromp, 1st Governor of Aruba

- Evelyn Wever-Croes, 4th Prime Minister of Aruba, first female Prime Minister

See also

- Bibliography of Aruba

- Central Bank of Aruba

- Index of Aruba-related articles

- List of monuments of Aruba

- Military of Aruba

- Outline of Aruba

- SS Pedernales

References

- ^ Migge, Bettina; Léglise, Isabelle; Bartens, Angela (2010). Creoles in Education: An Appraisal of Current Programs and Projects. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 268. ISBN 978-90-272-5258-6. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ a b https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/caribische-deel-van-het-koninkrijk/vraag-en-antwoord/waaruit-bestaat-het-koninkrijk-der-nederlanden

- ^ a b "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Aruba". Archived from the original on 15 May 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "CIA World Factbook - Aruba". Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Historia di Aruba". Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Brushaber, Susan; Greenberg, Arnold (2001). Aruba, Bonaire & Curacao Alive!. Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-58843-259-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Aruba History". Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Rock Formations". Aruba.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ Sullivan, Lynne M. (2006). Adventure Guide to Aruba, Bonaire & Curaçao. Edison, NJ: Hunter Publishing, Inc. pp. 57–58. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ Sauer, Carl Ortwin (1966). The Early Spanish Main. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 112. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Sitios de Memoria de la Ruta del Esclavo en el Caribe Latino". www.lacult.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ a b Dede pikiña ku su bisiña: Papiamentu-Nederlands en de onverwerkt verleden tijd. van Putte, Florimon., 1999. Zutphen: de Walburg Pers

- ^ Van Putte 1999.

- ^ "British Empire: Caribbean: Aruba". Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Albert Gastmann, "Suriname and the Dutch in the Caribbean" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 5, p. 189. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ^ Central American and Caribbean Air Forces, Daniel Hagedorn, Air Britain (Historians) Ltd., Tonbridge, 1993, p.135, ISBN 0 85130 210 6

- ^ Robbers, Gerhard (2007). Encyclopedia of World Constitutions. Vol. 1. New York City: Facts on File, Inc. p. 649. ISBN 0-8160-6078-9. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Status change means Dutch Antilles no longer exists". BBC News. BBC. 10 October 2010. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "BBC News — Aruba profile — Timeline". BBC. 5 November 2013. Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b Canoe inc. (22 June 2011). "Aruba: the happy island". Slam.canoe.ca. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Cities in Aruba - Guide to Aruba's Biggest Cities". Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Aruba Central Bureau of Statistics (29 September 2010). Fifth Population and Housing Census, 2010: Selected Tables (PDF) (Report). pp. 75–76. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Climate Data Aruba". Departamento Meteorologico Aruba. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Dewar, Robert E. and Wallis, James R; 'Geographical patterning in interannual rainfall variability in the tropics and near tropics: An L-moments approach'; in Journal of Climate, 12; pp. 3457–3466

- ^ "Summary Climatological Normals 1981–2010" (PDF). Departamento Meteorologico Aruba. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "About Us". DutchCaribbeanLegalPortal.com. Archived from the original on 20 June 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ "History of Aruba in Timeline - Popular Timelines". populartimelines.com. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Dede pikiña ku su bisiña: Papiamentu-Nederlands en de onverwerkt verleden tijd. van Putte, Florimon., 1999. Zutphen: de Walburg Pers

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency (2009). "Aruba". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "Aruba - arubanoasis". www.arubanoasis.com. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "Political Stability". Aruba Department of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ "EU Relations with Aruba". European Union. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT)". European Union. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "Best Things to do in Aruba - Aruba.com". www.aruba.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013.

- ^ "Korps Politie Aruba: district precincts". Aruba Police Force. Archived from the original on 26 February 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ Central Bureau of Statistics. "Key Indicators General Government, 1997–2006". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ Kingdom of the Netherlands - Aruba: 2019 Article IV Consultation Discussions - Press Release and Staff Report (Report). International Monetary Fund. 2019. p. 9.

- ^ "Aruba Foreign Affairs". arubaforeignaffairs.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ "Bogaerts: USA TODAY Sports' Minor League Player of Year". Usatoday.com. 3 September 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ webmaster@visitaruba.com. "Aruba Education - Schools and Universities - VisitAruba.com". www.visitaruba.com. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Hands for Ziti: Teacher & Students from International School of Aruba Team Up to 3D Print e-NABLE Prosthetics | 3DPrint.com | The Voice of 3D Printing / Additive Manufacturing". 3dprint.com. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ "Schakel College in Tilburg • Tilburgers.nl - Nieuws uit Tilburg". Tilburgers.nl - Nieuws uit Tilburg (in Dutch). Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ "Aureus University School of Medicine". Aureusuniversity.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ "Caribbean Medical School - Xavier University". Caribbean Medical School - Xavier University. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ CIA (10 September 2019). "Aruba". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Country Trends". Global Footprint Network. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Lin, David; Hanscom, Laurel; Murthy, Adeline; Galli, Alessandro; Evans, Mikel; Neill, Evan; Mancini, MariaSerena; Martindill, Jon; Medouar, FatimeZahra; Huang, Shiyu; Wackernagel, Mathis (2018). "Ecological Footprint Accounting for Countries: Updates and Results of the National Footprint Accounts, 2012-2018". Resources. 7 (3): 58. doi:10.3390/resources7030058.

- ^ "Convert Dollars to Aruba Florin | USD to AWG Currency Converter". Currency.me.uk. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Convert United States Dollar to Aruban Florin | USD to AWG Currency Converter". Themoneyconverter.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ "Toerisme Aruba naar recordhoogte" (in Dutch). Antilliaans Dagblad. 5 May 2019. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ "Aruba". HighEnd-traveller.com. 31 May 2016. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "History of Aruba in Timeline - Popular Timelines". populartimelines.com. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Street car is up and running Archived 5 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine The Morning News, 27 February 2013

- ^ "Aruba Hosts International Desalination Conference 2007". Aruba Tourism Authority. 18 July 2007. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "History". W.E.B. Aruba NV. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ "Setar N.V." Setar N.V. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ "Mio Wireless". Archived from the original on 19 June 2014.

- ^ "Flamingo Beach". Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

External links

- Official website of the government of Aruba

- Aruba.com – Official tourism website of Aruba

- Aruba

- 10th-century establishments in Aruba

- 1499 establishments in the Spanish Empire

- 1636 disestablishments in the Spanish Empire

- 1636 establishments in the Dutch Empire

- 1799 disestablishments in the Dutch Empire

- 1799 establishments in the British Empire

- 1802 disestablishments in the British Empire

- 1802 establishments in the Dutch Empire

- 1804 disestablishments in the Dutch Empire

- 1804 establishments in the British Empire

- 1816 disestablishments in the British Empire

- 1816 establishments in the Dutch Empire

- 1986 disestablishments in the Netherlands Antilles

- 1986 establishments in Aruba

- Caribbean countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

- Dutch-speaking countries and territories

- Former Dutch colonies

- Islands of the Netherlands Antilles

- Populated places established in the 10th century

- Small Island Developing States

- Special territories of the European Union

- States and territories established in 1986

- Dependent territories in the Caribbean