Coal mining in Plymouth, Pennsylvania

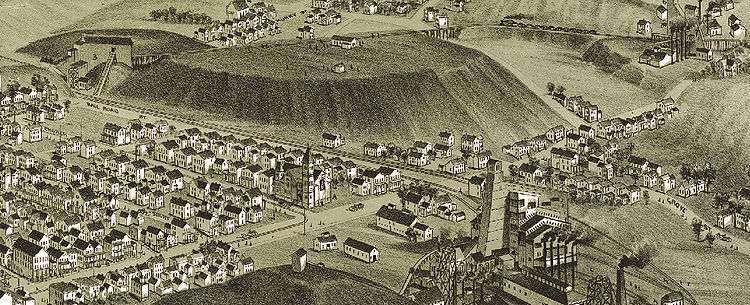

Plymouth, Pennsylvania sits on the west side of Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley, wedged between the Susquehanna River and the Shawnee Mountain range. Just below the mountain are hills that surround the town and form a natural amphitheater that separates the town from the rest of the valley. Below the hills, the flat lands are formed in the shape of a frying pan, the pan being the Shawnee flats, once the center of the town's agricultural activities, and the handle being a spit of narrow land extending east from the flats, where the center of town is located. At the beginning of the 19th century, Plymouth's primary industry was agriculture. However, vast anthracite coal beds lay below the surface at various depths, and by the 1850s, coal mining became the town's primary occupation.

Coal mining in Plymouth, Pennsylvania

The Smith Coal Mines

About 1806, Abijah Smith came to Plymouth from Derby, Connecticut, intending to mine, ship, and sell coal. Smith and his business partner Lewis Hepburn, bought a 75-acre plot (called Lots 45 and 46) on the east side of Coal Creek, and in the fall of 1807, Smith floated an ark down the Susquehanna River loaded with about fifty tons of anthracite coal, and shipped it to Columbia in Lancaster County. The significance of Smith's shipment went unnoticed until 1873, when Hendrick B. Wright wrote in his Historical Sketches of Plymouth:

"Anthracite coal had been used before 1807, in this valley and elsewhere, in small quantities in furnaces, with an air blast; but the traffic in coal as an article of general use, was commenced by Abijah Smith, of Plymouth."

Beginning with the fifty tons of coal shipped by Abijah Smith in 1807, Plymouth's and the Wyoming Valley's coal industry grew steadily. In 1830, the Baltimore Patriot reported that "... a greater quantity of Anthracite Coal has been sent down the Susquehanna this Spring than in any former season. The Baltimore Company have sent three thousand tons, and from other mines about seven thousand tons were dispatched, making an aggregate of ten thousand tons."[1]

The North Branch Canal

As late as the 1840s, whenever high water allowed, coal from Wyoming Valley's coal mines was shipped down the Susquehanna River on wooden arks. But by the end of 1830, canal boats began to replace arks as the preferred method of transporting coal and other goods to market. In 1826, the Pennsylvania Board of Canal Commissioners engaged John Bennett to survey the route of a new canal, to be called the North Branch Canal, to run alongside the north branch (the main branch) of the Susquehanna River from Northumberland to the New York border. In early 1827, Bennet reported that the canal was feasible, and in 1828, the state legislature authorized funds for construction. Charles T. Whippo—who had worked on the construction of the Erie Canal—was engaged to survey the route and supervise construction. The southern portion of the canal, as built, ran for 55.5 miles (89.3 km) along the west side of the river, from Northumberland to West Nanticoke, where a dam at Nanticoke Falls was built to divert water from the river into the canal. The work was generally complete by the fall of 1830. The first load of coal shipped from the Wyoming Valley reached Berwick in October.[2]

The canal was a boon to Plymouth's coal operators—who in 1830 included John Smith, Freeman Thomas, Henderson Gaylord, and Thomas Borbidge—and it encouraged others—such as Jameson Harvey and Jacob Gould—to open mines. Smith's teamsters led teams of horses deep into his mine, turned the team, loaded the wagon and then drove the team to the river bank to load the coal into canal boats. Gaylord—whose mine was at the base of Welsh Hill—improved on this method and built a gravity railroad that ran along what is now Walnut Street, down what is now Gaylord Avenue, to his wharf on the river.[3] A similar road—called the Swetland Railroad—was built from mines in Poke Hollow down a route which later became Washington Avenue, across Bull Run to another wharf on the river. Freeman Thomas built a railroad from his Grand Tunnel mine to a chutehouse along the river near the entrance to the canal.

The early coal mines in Plymouth supported an ancillary industry: boat building. The arks used to transport goods on the river were built in a basin where Wadham's Creek entered the river. After the canal was built, the arks began to be replaced by flat-bottomed canal boats, built in the same basin with a distinctive design known as "Shawnee boats." Many of the town's young men became boatmen and were well known along the length of the canal for their distinctive call, "Shawnee against the World."[3]

The Lackawanna & Bloomsburg Railroad

The 1858 Anthracite Map, prepared as part of the First Pennsylvania Geological Survey, illustrates Plymouth's mines and collieries at a moment of transition. The Lackawanna & Bloomsburg Railroad was largely completed and had begun to replace the North Branch Canal as the preferred method for shipping coal. In 1858, most mines in Plymouth were tunnels driven into the hillside above water level, with one exception: a shaft had been sunk in 1856 at the Patten Mine by experienced miners from England and Scotland. It was the first deep mine shaft in Plymouth and the first on the west side of the river—a harbinger of things to come. In 1858, all of Plymouth's mines were run by small local operators. This would soon change as large corporations, some affiliated with railroads, began to take control of much of the town's coal lands. The larger firms would be better able to handle labor disputes, and had the necessary capital to conduct deep shaft mining and operate the mines on a larger, more efficient scale.

The 1858 map (below), illustrates the path of the railroad. Several collieries appear at the west end of Plymouth, including the Harvey Mine, Grand Tunnel, Reynolds (Chauncey), French Tunnel (Jersey Mine), Reynolds (Washington Mine) and the Smith mine operation at the upper end of Coal Creek. The Wadhams mine appears along Wadhams Creek above Plymouth Village. A railroad branch line (Gaylord's Railroad) is shown running along Pine Swamp Creek (later Brown's Creek). One branch of this railroad crossed what later became Bull Run and led to a wharf along the Susquehanna River. Another branch railroad ran down to Henderson Gaylord's wharf, near what is now Gaylord Avenue. The Patten mine and Cooper mine (labeled as Galard) are shown along the creek. East of Plymouth village, John Shonk's colliery, called Rudmandale, appears where the Lance Colliery would later be, and above that, Shupp's Creek and Ross Hill are illustrated just before the Boston Mine was established.

Coal Mines in Plymouth, Pennsylvania

The Susquehanna Coal Company Mines

The Harvey Mine

Jameson Harvey was born in 1796, the son of Elisha Harvey and his wife, Rosanna Jameson. Harvey's farm, about 350 acres (1.4 km2), was located in Plymouth Township on the east side of the intersection of Harvey's Creek and the Susquehanna River. In 1832, he built a Federal-style farmhouse and barn, both of which still stand today greatly altered, on what is now McDonald Street. By 1830, probably inspired by his neighbor Freeman Thomas's Grand Tunnel coal mine, Harvey supplemented his farm income by constructing a coal tunnel. Perhaps learning from Thomas's experience, Harvey's tunnel was higher up the hill, and thus a shorter distance from the coal beds. Later, Harvey constructed one of Plymouth's first coal breakers. His mine was closer than any other to the Nanticoke Dam and the entrance to the North Branch Canal, and when the railroad arrived, it ran right across Harvey's property. These geographical advantages helped make the mine a very successful venture. In 1869, Harvey moved to Wilkes-Barre, and in 1871, he sold his coal lands to the Susquehanna Coal Co., which merged Harvey's mine with the Grand Tunnel into a new operation called the Susquehanna Coal Co. Colliery No. 3.[4]

The Grand Tunnel

Freeman Thomas was an early land owner in Plymouth. In 1809, he acquired several patents for lots in the lower end of the township, calling his estate "Harmony", better known in later years as the "Grand Tunnel". About 1828, Thomas began to dig a tunnel through solid rock into the hillside, hoping to reach the famed Red Ash coal vein.[5] He must have succeeded by 1834, for on the 6th of August that year, he petitioned the courts for the right to build a gravity railroad from his tunnel to a chute house along the Susquehanna River just above the Nanticoke Dam.[6] The private railroad allowed Thomas to ship his coal to the iron forges in Danbury and to other points south via the newly built North Branch Canal. Thomas died in 1847,[5] and in 1852, William L. Lance, Sr. became a tenant of Thomas's children. Lance operated the mine until 1856, when he assigned his lease to the Mammouth Vein Coal Co. In January 1860, Mammouth abandoned Thomas's chutehouse and built a new one adjacent to the recently built Lackawanna & Bloomsburg railroad.[6] In 1866, the Grand Tunnel Coal Co. operated the mine,[7] and in 1871, the New England Coal Co. operated the mine. In 1871, the Susquehanna Coal Company took control of the Grand Tunnel.[8] By 1935, the Glen Alden Coal Co. operated the Grand Tunnel but in September that year they leased the mine to George F. Lee, owner of the adjacent Chauncey Colliery.[9]

Susquehanna Coal Co. No. 3 Colliery

In 1871, the Susquehanna Coal Company, owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad, took control of both the Harvey Mine and the Grand Tunnel, although James Hutchison stayed on as mine boss.[8] After a boiler explosion in 1871, the SCC took down the old Harvey breaker and on July 27, 1872 began operating a new one, considered to be one of the largest in the district. It was designed by Charles F. Ingram, a mining engineer from Wilkes-Barre, and built by James Linskill, a carpenter from Plymouth.[10]

The Chauncey Colliery

The Chauncey Colliery was located between the Grand Tunnel and the Avondale collieries. It was one of the few Plymouth collieries to remain independent of the large mining corporations. The mine was most likely named after Chauncey A. Reynolds of Plymouth, who was working at the site as early as 1831.[11] Reynolds was said to have driven the first tunnel,[12] although another source attributes the name to Thomas Chauncey James, a veteran of the War of 1812 and for a time the postmaster of the Grand Tunnel post office.[13] The Chauncey was also known as the Union Mine, and from about 1861 to 1866 the Union Coal Co., in association with Charles Hutchison, operated the mine, working both a shaft and a slope. At the time, capacity was about 50,000 tons per year.[7]

From at least 1869 until at least 1875, the mine was operated by Roberts, Albrighton & Co., and John Albrighton, the mine boss, employed about 100 men.[14] In 1875, a major cave caused a stoppage of work at both the Chauncey and the adjacent Grand Tunnel mine.[15] In 1880, the mine was operated by B. B. Reynolds.[16] In 1881, Thomas P. MacFarlane was the operator and 24,515 tons were shipped.[17] In 1891, MacFarlane still operated the mine.[18] By 1896, Reynolds & Moyer Coal Co. operated the Chauncey,[19] but in July 1900, it was put up for Sheriff's sale, subject to the many complicated leases among members of the Reynolds family.[20]

The next operator of the Chauncey, George F. Lee, was the son of Conrad Lee, from 1865 to 1886 the outside foreman of the nearby Avondale Colliery where George F. Lee was born in 1870. He purchased the Chauncey in 1902, and operated it as the George F. Lee Coal Co. He also ran a coal distribution center in Brooklyn, New York.[21] In 1914, the Chauncey processed about 6,600 tons per month.[22] In 1919, Lee built a new breaker with a capacity of 1,000 tons daily, which began operating on August 25. The breaker, designed by Frank Davenport, an engineer from Wilkes-Barre,[23] was destroyed by fire on January 28, 1923, the loss estimated to be $250,000. The following day, Lee engaged E. E. Reilly of Kingston to build a new breaker.[24] At the end of 1936, the George F. Lee Coal Co. still worked both the Chauncey mine and breaker,[25] producing 38,712 tons of coal, but by 1940, the company was bankrupt and in receivership. In 1940, the Glen Alden Coal Company took ownership of the colliery, and in February 1941 began to dismantle the breaker.[26]

The Avondale Colliery

In November 1808, Hezekiah Roberts, Jr. obtained patents on five lots in the western end of Plymouth Township, about 120 acres (0.49 km2) total. He called his estate "Avondale", and it eventually gave its name to the colliery. After receiving these patents Roberts sold his soon-to-be valuable coal lands, and by 1810 was farming in Genoa Township, Delaware County, Ohio.[27] In addition to Roberts' 120 acres (0.49 km2), the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad compiled a large number of lots, including part of Freeman Thomas's Grand Tunnel property. If one includes the Wright family's 225 acres (0.91 km2) that comprised the Jersey mine, the DL&W's Avondale holdings included over 600 acres (2.4 km2).

The Delaware, Lackawanna and Western took a circuitous path to ownership of Avondale because its 1854 charter limited its ownership of coal lands. As a result, it used surrogates to acquire coal properties.[28] In 1863, John C. Phelps, a director of the DL&W, leased a portion of the Avondale property from William Reynolds and Henderson Gaylord, Plymouth natives. In 1866, the mine was transferred to the Steuben Coal Co., which in turn became part of the Nanticoke Coal & Iron Co., whose board of directors overlapped with the board of the DL&W. The NC&I built the first breaker at Avondale.[29]

On September 6, 1869, the Avondale Mine Disaster occurred, during which a fire in the shaft, ignited by a ventilating furnace, spread to the breaker which stood over the mine shaft. The breaker was destroyed by fire, trapping 108 men and boys in the mine below. All were killed, as were two men who volunteered to enter the mine after the fire. Soon after the disaster, a second breaker was built at the colliery.[29]

In 1914, the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western operated both the mine and the breaker.[22] On February 9, 1935, Glen Alden Coal Co. (successor to the DL&W) began to dismantle and demolish the Avondale breaker and to close the mine.[30] In 1936, no coal was produced. However, in December 1940, Glen Alden resumed mining on a limited scale taking coal to the Lance Breaker to be processed.[31] In 1955, the Avondale operation produced 78,401 tons of coal.[32]

Red Ash Colliery

George P. Lindsay, the general manager of the Plymouth Red Ash Coal Co., began mining in 1913, and began building a breaker to process coal in 1914. The operation was, therefore, a latecomer among Plymouth's many mine operations. The colliery was located along Route 11, just east of the Avondale Colliery. In 1915, the mine produced 14,311 tons of coal. In 1931, its peak year, the mine produced 78,575 tons of coal. The breaker was demolished in 1942.

The Jersey Colliery

The Jersey was one of Plymouth's oldest mines, a tunnel located at the top of Jersey Road in the hollow between Avondale Hill and Curry Hill, just west of the Plymouth Borough boundary. The mine was located on two lots of about 225 acres (0.91 km2), patented to Ellen Wadhams (1776–1872) in 1808 by virtue of the claim of her late husband Moses Wadhams (1776–1803). The mine was established by Joseph Wright (1785–1855), Ellen's second husband, a Quaker who migrated to Plymouth from New Jersey. Wright's stepdaughter, Lydia Wadhams (1803–90), married Samuel French (1803–66) who became the second operator of the Jersey. French, who was the stepson of Plymouth mine operator John Smith, operated the mine until about 1855, when the Scottish immigrant Robert Love, then a young man in his twenties, took control. Love built a gravity railroad from the mine down to the newly arrived Lackawanna & Bloomsburg Railroad and supplied the L&B with the first coal shipped from Plymouth by rail.[3]

By 1865, the Jersey was operated by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad and had an estimated annual capacity of 50,000 tons.[7] In 1871, and in accordance with laws enacted following the 1869 disaster at the adjacent Avondale mine, the DL&W sank an 10-foot (3.0 m) X 14-foot (4.3 m) air shaft at the Jersey to help ventilate the mine.[33] A breaker sat on the hill just below the mine as early as 1885. The DL&W operated the Jersey until 1902, when an underground mine fire broke out. As of 1942, the DL&W's successor, the Glen Alden Coal Co., was still trying to extinguish the fire.[34]

The Nottingham Colliery

As perfected by 1908, the Nottingham Colliery included the mines established by Abijah and John Smith, and the Washington mine. All four operations have separate histories:

Abijah Smith's Mine

Vast anthracite coal beds lay below Plymouth's surface at various depths. At a few locations these beds were visible in the form of outcrops, and one such location was a gorge created by Ransom Creek (now Coal Creek) located about a mile upstream from the Susquehanna River. Coal could be seen (and accessed) on both the east side (Turkey Hill) and the west side (Curry Hill) of the creek. Attracted by this outcrop, Abijah Smith came to Plymouth about 1806, and with his business partner Lewis Hepburn, bought a 75-acre plot (called Lots 45 and 46) on the east side of the creek, intending to mine, ship and sell coal.

Smith was born in Derby, Connecticut, about 1763, where he married and fathered numerous children. He worked as a blacksmith or harness maker. In 1804, he advertised: "For sale by Abijah Smith, at Derby Landing, Skirting and Bridle leather, of the first quality, May 7, 1804.[35] It is not known exactly why Smith left Derby for the Wyoming Valley, but one journalist reporting in 1901 related an anecdote that had been passed down through the years. "The story is that Abijah Smith heard through some man, who had been traveling in Pennsylvania, and who passing through Derby on his way home stopped at Smith's blacksmith shop to have his horse shod, about black stone in Pennsylvania that would burn. The result of this conversation was that Smith made a trip to Pennsylvania and eventually located there ... He left Derby in 1806 and in 1807 mined 56 tons of coal in Plymouth, Pa. at the old mine now rented to the Lehigh and Wilkes-Barre Coal Co., and known as the Smith red ash coal."[36]

According to Hendrick B. Wright, in the fall of 1807, Abijah Smith purchased an ark from John P. Arndt, a Wilkes-Barre merchant, which Arndt had used for the transportation of plaster. Smith floated the ark from Wilkes-Barre to Plymouth, loaded it with about fifty tons of anthracite coal, and shipped it to Columbia, in Lancaster County.[5] According to Wright:

"...this was probably the first cargo of anthracite coal that was ever ordered for sale in this or any country. The trade of 1807 was fifty tons ... Abijah Smith therefore, of Plymouth, was the pioneer in the coal business. Anthracite coal had been used before 1807, in this valley and elsewhere, in small quantities in furnaces, with an air blast; but the traffic in coal as an article of general use, was commenced by Abijah Smith, of Plymouth."

In 1825, Thomas Borbidge, of Kingston, Pennsylvania assumed operation of the mine, and in 1827, he and John Smith (operator of the mine across the creek) petitioned the Pennsylvania House of Representatives for permission to build a railroad from their mines to the Susquehanna River.[37] In 1830, Borbidge was still operating the mine.[38] By 1835, the mine belonged to John Ingham (married in 1827 to Abijah Smith's widow), who lost it that year in a Sheriff's sale.[39] By 1873, the mine was owned by Hendrick B. Wright, and leased to Broderick, Conyngham & Co., operators of the Nottingham Colliery.[40]

John Smith's Mine

In 1805, Hezekiah Roberts, Sr. obtained a patent for 121 acres (0.49 km2) of land, called Lot 44, on the west side of Coal Creek, which he sold to William Currie (who gave the place the name Curry Hill). In July 1810, Currie advertised in the newspaper: "for sale...an extensive coal bed...situated one mile from the river." He soon sold the mineral rights to Lewis Hepburn (Abijah's Smith's partner), and in 1811, Hepburn sold half of these rights to John Smith (Abijah Smith's brother). In 1816, after Lewis Hepburn died, Hepburn's son Patrick sold Smith the second half of the coal rights.

John Smith operated his mine on the west side of Coal Creek from 1811 until about 1837. A visitor in 1830 described Smith's coal mine as having a 20-foot (6.1 m) thick bed of coal, and found the mine "extensively wrought, and the scene both without and within is exceedingly imposing. The bed is followed into the mountain, large pillars of coal being left to support the superincumbent weight." The visitor noted that in some areas Smith had removed all of the coal, leaving only a roof of slate which then caved in. As a result, Smith modified his technique to leave two feet of coal to form the ceiling.[41]

In 1840, John Smith leased his coal beds to his son, Francis J. Smith, his stepson, Samuel French, and his sons-in-law, Draper Smith and William C. Reynolds. In 1848, Smith sold the coal rights to Lot 44 outright to Reynolds.[42] By 1873, the mine was owned by Mrs. William C. Reynolds, and leased to Broderick, Conyngham & Co., operators of the Nottingham Colliery.[40]

Washington Colliery

The Washington Colliery was first opened by John Shay about 1854. Shay built a drift, an inclined plane, and a breaker. Shutz, Shay & Heebner operated the colliery until August 1869, when they sold their rights to Broderick, Conyngham & Co. At the same time, BC&C entered into leases to operate the Nottingham Colliery, the old John Smith mine and the old Abijah Smith mine, and from then on all four mines were operated under common management. On April 1, 1872 BC&C sold their lease to the Lehigh Navigation & Coal Co., and on January 1, 1874, the LN&C sold to the Lehigh & Wilkes-Barre Coal Co. which operated the mine as the Reynolds No. 16.[29] By April 1890, the first breaker had been dismantled and a new breaker was in operation. In 1908, the L&W-B abandoned the second breaker and began to process coal from the Washington mine at the Nottingham breaker. In March 1912, the company destroyed the Washington breaker with dynamite.[43]

Nottingham Colliery

The Nottingham Coal Co. of Baltimore was incorporated on March 21, 1865, and obtained a lease to mine coal from Plymouth's Reynolds family, a lease which would bring the family great wealth. Bryce R. Blair was named superintendent, and proceeded to construct a coal breaker and a 380-foot (120 m) shaft, said to pass through 40 feet (12 m) of quicksand on its way to the coal beds below.[44]

In August 1869, the Nottingham assigned their lease to the firm of Broderick, Conyngham & Co.[29] In order to create a second means of egress from the mine, as required by the mine safety law enacted after the 1869 Avondale Mine Disaster, BC&Co. drove 2,400 feet (730 m) to the west to connect with its Washington mine.[8] On April 1, 1872 BC&Co. sold their lease to the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company, and on January 1, 1874, the LC&N sold the property to the Lehigh & Wilkes-Barre Coal Co. which operated the mine as the Nottingham No. 15 Colliery.[29]

In 1936, the Glen Alden Coal Co. operated the Nottingham and produced 263,836 tons of coal. However, in August 1936, Glen Alden demolished the Nottingham breaker,[45] part of a general consolidation of mine operations in the Wyoming Valley. Thenceforth, coal from the Nottingham was processed at the Lance breaker. The lone voice of protest of the Nottingham's demise was the Luzerne County Communist Party, whose presidential candidate, Earl Browder, called upon the community to raise its voice against "this wrecking plan of the coal companies."[46] In December 1936, Glen Alden operated the Nottingham for the first time since the breaker's demolition, and after a subsequent period of idleness, resumed operations at the Nottingham again in 1938.[47] The mine continued to operate into the 1950s. In June 1954, Charles Medura was killed in the mine by a fall of rock, the last of many fatalities at the mine.

The Parrish Colliery

The Parrish Colliery was a relative late-comer to Plymouth. Its origins can be traced to the sale by the Wadhams family of their homestead farm in 1871 to the Wilkes-Barre Coal & Iron Co. The property was located in the center of Plymouth Borough, between Academy and Girard streets. In 1874, the Wilkes-Barre Coal & Iron Co. became part of the Lehigh & Wilkes-Barre Coal Co., which acquired the property, but by some arrangement the mine was operated by the Parrish Coal Co., organized in 1884. The company built a breaker, said to be "a model of neatness,"[48] built by contractor Joseph C. Tyrrell and completed in September 1884.[49] On the night of January 25, 1887, the new breaker caught fire and was completely destroyed. Another was built and was operating by July.[50]

By 1914, the mine had reverted to the Lehigh & Wilkes-Barre Coal Co. which operated a washery and breaker. Ash and waste water from the washery were flushed into the Susquehanna River.[22] In June 1914, the company closed the Parrish breaker and began construction of a tunnel under the river to transport coal to the company's breaker in Buttonwood.[51] In 1920, the Glen Alden Coal Co. acquired the Lehigh & Wilkes-Barre Coal Co., including the Parrish Colliery, and in July of that year the breaker blew down in a wind and rain storm.[52]

The Dodson Colliery

The Dodson Colliery was located at Bull Run in Plymouth Borough, and its breaker stood alongside the tracks of the Lackawanna & Bloomsburg Railroad. The Dodson's coal lands ran from Center Avenue on the west to Pierce Street on the east, and thus the Dodson's mining operations took place beneath the central business district of the Borough. The colliery was first developed by Fellows & Dodson, Co., beginning in 1869, and by 1870 a large breaker had been built and a shaft sunk to a depth of 220 feet (67 m).[53]

By 1872, the mine was operated by the Wilkes-Barre Coal & Iron Co. which had recently gained control of nearly all of Plymouth Borough's coal lands east of Academy Street, including the Lance and the Gaylord collieries. In 1872, the company employed 80 men at the Dodson, sank the shaft to a depth of 280 feet (85 m), and began to experience problems with water infiltration.[54] In 1874, the Wilkes-Barre Coal & Iron Co. merged into the Lehigh & Wilkes-Barre Coal Co., but by early 1877 this firm was overextended and (temporarily) in receivership.

In 1877, the Plymouth Coal Company, managed by John J. Shonk and John C. Haddock, gained control of the Dodson. In October 1877, the Wilkes-Barre Times reported that "work is to be resumed at the Dodson shaft by the Plymouth Coal Co."[55] In 1882, Haddock assumed sole control of the Plymouth Coal Co., and ran the Dodson until his death in New York in December 1914. Haddock had a litigious reputation due to his disputes with neighboring mines, with Plymouth Borough and with Plymouth's Sweitzer family. He disputed freight rates, testifying before the Interstate Commerce Commission that the railroads discriminated against small operators.[56]

On July 13, 1899, the first Dodson breaker burned down, and on March 5, 1900, work began on the second breaker.[57] In 1914, Plymouth Borough obtained an injunction preventing the Plymouth Coal Co. from mining, owing to surface subsidence, and for most of that year the mine was idle. In January 1915, the Kingston Coal Co., which operated the adjacent Gaylord Colliery, announced it would buy the Dodson mine.[58]

The Lance Colliery

In his will of 1834, Jacob Gould bequeathed to his seven children "all the coal mines which are now or may hereafter be found on any part of my landed property ... and that there shall be a reserve made in the division of my real or landed property sufficient for all necessary roads to go to and from said coal mines and sufficient land for to deposite all coal and coal dirt and the like that is necessary, and that each one shall have an equal right to dig or mine coal at any time, and each one shall be at their proper expense of keeping said coal mine or mines in repair according to what coal they may dig or mine." He further willed that with respect to "the division of all my coal mines ... each daughter is made equal to each son and holding equal rights & interest..." Twenty-four years later, the 1858 Pennsylvania Geological Survey reported that "coal has been wrought languidly for thirty years" at "Gould and Shunk's mine", the operator being John Jenks Shonk, and the mine called Rudmandale, located just west of Shupp's Creek.[59] The small operation eventually became the Lance Colliery, one of Wyoming Valley's largest and most enduring.

Despite its name, the Lance Colliery was controlled by William L. Lance, Sr. for a very short time. About 1865, Lance and his sons bought the Gould Homestead, which ran from the Susquehanna River to State Street, just east of the Plymouth Borough line. The land contained about 150 acres (0.61 km2) of coal measures. In order to develop the property by sinking a deep shaft to reach the coal seams, and building a breaker to process the coal, Lance borrowed money from Payne Pettebone, a coal mine operator. Lance overextended himself, and Pettebone aggressively pursued repayment. In January 1871, Lance's friend, Samuel Bonnell, Jr., bought the property at Sheriff's Sale so as to satisfy the debt. Bonnell allowed Lance and his sons to continue to operate the mine.[60] As of 1871, Lance had sunk the shaft 175 feet (53 m), and was in process of sinking a second shaft for emergency egress.[61] However, in July 1871, Bonnell sold the improvements and leased the coal rights to the Wilkes-Barre Coal & Iron Co., and in February 1876, Bonnell sold the property outright to the Lehigh & Wilkes-Barre Coal Co.[60] Lance, who moved to Philadelphia and became a mat manufacturer, spent years in court, suing his old friend Bonnell in a futile attempt to recover the mine.

According to The Engineering and Mining Journal, in 1879 the Lance Colliery was operated by Charles Parrish & Co., a subsidiary or tenant of the L&W-B. The journal reported that "the mine having been idle for about a year, has again been started up."[62] In 1883, William Lance's old breaker was torn down and on June 30, 1883 the Lehigh & Wilkes-Barre Coal Co. began shipping coal from a new breaker,[63] one that was constructed with 700,000 feet of Georgia pine.[64]

In 1931, the Glen Alden Coal Co., successor to the L&W-B, erected a third breaker. By this time, large coal companies were more concerned about their public image, and Glen Alden made an effort to make the building and grounds attractive. Writing in 1941, a newspaper reporter described the colliery as "beautifully landscaped."[65] In 1936, Glen Alden produced 653,141 tons of coal, and in 1945 produced 489,889 tons of coal. In 1955, the Lance breaker produced 44,534 tons of coal, and remained active as late as 1957.[32]

The Gaylord Colliery

The Gaylord was opened about 1854 by Henderson Gaylord, who built a private railroad from the colliery across what was then the Nesbit family farm to a wharf on the river near the corner of Gaylord Avenue and Main Street. Gaylord leased the mine to Van Homer & Fellows, then to Eric L. Hedstrum (of Buffalo, New York).[29] In 1866, J. Langdon & Co. (later H.S. Mercur & Co.) operated the mine.[7] Beginning in 1871, the Wilkes-Barre Coal & Iron Co. and then its successor, the Lehigh & Wilkes-Barre Coal Co., operated the mine, but this firm fell into receivership in 1877 and lost their lease. The Gaylord Coal Co., operated by Thomas Beaver and Daniel Edwards, took control of the Gaylord, and later merged with the Kingston Coal Co.

On March 5, 1879, the breaker at the Gaylord was destroyed by fire.[66] and on June 11, 1879, the Wilkes-Barre Record announced that Alanson Tyrrell of Kingston had been awarded a contract to build a new breaker.[67] In August 1879, The Engineering and Mining Journal wrote, "the Gaylord Coal Co. is building a new breaker in place of the one burned down last summer, and which is to prepare the coal from the old slope workings, with its tunnel to the seven foot seam, as well as the coal from its new shaft which was sunk by the Lehigh & Wilkes-Barre Coal Co., when it had it, to the Bennett seam. The new firm contemplates sinking down through the Bennett to the Red Ash seam. The coals from the Seven Foot and the Red Ash will cause it to be a very fine colliery."[68] The prediction proved accurate: in 1887, the Gaylord shaft and slope mined 248,276 tons of coal.[50]

On February 13, 1894, the Scranton Republican reported a large cave-in at the Gaylord mine: "We are called upon to detail the awful scenes of another miner horror. Thirteen men who went down to repair some damaged work-lugs in the Gaylord slope at Plymouth are caught by a fall of coal and most probably called to the great beyond, their bodies crushed and very little hope entertained for their recovery for days to come." On February 14, The Wilkes-Barre Record reported one hundred men were digging for the entombed miners. Despite these efforts, the situation was hopeless. On February 19 the Wilkes-Barre Record reported that ground water in the Gaylord was hindering the rescue. Finally on March 12 the body of Peter McLaughlin was recovered, the first of the miners to be found. By April 6, the last of the bodies was taken out of the mine, that of the foreman, Thomas Picton.

According to the Water Supply Commission of Pennsylvania, in 1914 the colliery was still operated by the Kingston Coal Co., producing about 225 tons of coal per day. Slush and waste water were pumped into three boreholes, rather than into Brown's Creek, and washwater was pumped from the Susquehanna River, 23,000,000 gallons in four months.[22]

In May 1935, the Glen Alden Coal Co. bought the Gaylord mine from the Kingston Coal Co. for $100,000. Glen Alden paid about $40,000 in back taxes owed to Plymouth Township, Plymouth Borough and Larksville Borough.[69] On June 15, 1935, the second Gaylord breaker was demolished with dynamite.[70] By this time, the mine was largely depleted, but in December 1940, the Sunday Independent reported that "the old Gaylord mine, now being operated by Samuel Bird, brother of Morgan Bird, is showing signs of being able to absorb additional number of men in the future...[the] Lance [breaker] prepares the coal."[71] In 1945, the Gaylord worked 284 days and produced 26,301 tons of coal, and In January 1955, the Bird Mining Co. stopped mining at the Gaylord.

Hillside Colliery

Hillside was a minor operation first worked by George W. Shonk and John Barry, operating as the Barry, Shonk & Dooley Coal Co., on land owned by the Barry family, old settlers on Plymouth Mountain above Poke Hollow. Coal was extracted by means of a slope dug into the side of the mountain. According to the newspapers, in November 1906, the colliery began "mining on a large scale" and a "breaker ... erected which has a capacity of several hundred tons daily."[72] In 1907, Shonk and Barry sold their interest in the mine to Bright Coal Co., owned by a group of investors from Scranton. The newspapers reported that mining operations would be "carried out on a much larger scale" than before.[73] In 1914, Bright Coal Co. still operated the Hillside. At the time, waste water from the mine was dumped into a tributary of Brown's Creek.[74] In 1917, Bright mined 10,252 tons.[75]

Delaware & Hudson Collieries Along Brown's Creek

Fuller's Shaft (Delaware & Hudson No. 5)

The former railroad crossing at Plymouth's Bull Run (long disappeared) was originally called Fuller's Crossing, after the mine operator J. C. Fuller. The railroad ran from his mine (and several others), crossed Main Street and continued down to a wharf on the Susquehanna River. Fuller's mine was located just above the Gaylord colliery along what is now Washington Avenue. According to Munsell, the shaft was sunk by the (old) Plymouth Coal Co. and J. C. Fuller in 1858.[29] In 1864, Fuller operated the mine, which produced 23,827 tons of coal, making it that year the fourth largest mine in the Plymouth district.[7] In 1871, operation of the mine was transferred from Fuller to the Northern Coal & Iron Co., a firm owned by the Delaware & Hudson Canal Co.[8] and by 1873, if not earlier, a breaker was operating at the mine.

The Loree (Delaware & Hudson No. 5)

On April 27, 1907, the No. 5 breaker burned to the ground, causing an "awe inspiring spectacle." At the time, the breaker had been abandoned by the D&H and was being used as a washery by the Rissinger Bros.[76] By 1909, a second breaker was built, intended to process coal from several D & H mines. In 1914, The D&H was operating both the breaker and a washery and waste water from these was dumped into Shupp's Creek,[74] not Brown's Creek, because the second breaker had been relocated from its original site to a new one farther south. In 1919, fire destroyed the second No. 5 breaker.[77] That year, a new reinforced concrete breaker, called the Loree No. 5 Breaker, was built to process coal from all of the D&H operations in Plymouth. The Loree continued to operate until 1965.[78]

Swetland Shaft (Delaware & Hudson No. 4)

The Swetland Shaft was located on the northwest corner of the intersection of Vine and State streets in the Poke Hollow section of what is now Larksville Borough. According to court records, William Patten and Thomas Fender established this mine in 1851.[79] About 1855, Patten and Fender contracted with an English immigrant, John Dennis (a future Plymouth burgess), to sink a shaft to the coal seams below. It was said to be the first mine shaft on the west side of the Susquehanna River.[80] In January 1857, William Patten died when he fell down the newly constructed shaft.[81] Fender continued to operate the mine, but on February 25, 1860, lost the property at sheriff's sale.[79] Josiah W. Eno built a breaker at the mine in 1857, which he operated until 1861.

A.C. Laning & Co. bought the mine, and subsequently John Jenks Shonk, Payne Pettebone and William Swetland bought the mine.[29] In 1865, J. Langdon & Co. operated the mine. According to Samuel L. French, David Levi, a Welshman, operated the mine, followed by A.J. Davis and Charles Bennett.[3] By 1870, J.C. Fuller operated the mine, and in 1871, the Northern Coal & Iron Co., a subsidiary of the Delaware & Hudson Canal Co., assumed operation of the mine. Michael Shonk was mine boss for both Fuller and the NC&I.[82] Between 1864 and 1873, a coal breaker was built on the site, and in 1901, the D&H dismantled the breaker. As of 1914, coal from the No. 4 shaft was hauled to the No. 5 breaker for processing, although a washery at the No. 4 prepared enough coal to run the colliery boilers.[74] As of 1925, the D&H continued to operate the mine, calling it the Loree No. 4.

Delaware & Hudson Collieries Along Shupp's Creek

Boston Colliery

The Boston was unique in that the mine and the breaker were originally built about 1-1/4 miles apart from one another. The mine and shaft were located north of State Street where it intersects with Shupp's Creek. A railroad was built from the mine along the creek down to the first Boston breaker, located next to and east of the old Shupp Cemetery at the bottom of Boston Hill. The mine was opened in 1857 by the Boston Coal Co., which leased to the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad in 1858, and sold to the Delaware & Hudson Canal Co. in 1868, subject to the lease of 1858.[29] In 1883, the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western mined 4,351 tons, but in January that year the Delaware & Hudson assumed operation of the mine.[83]

On January 16, 1887, the Boston breaker was destroyed by fire. The Delaware & Hudson built a second breaker, this time adjacent to the mine, completed by November 1887.[84] In 1909, the second Boston breaker was demolished and coal from the mine processed at the Delaware & Hudson No. 5 colliery.[85]

Delaware & Hudson No. 1 Colliery

The No. 1 colliery was the most westerly of three collieries constructed in the late 1860s along Shupp's Creek by the Northern Coal and Iron Co., located on Main Street on the east side of the creek. The Delaware & Hudson Canal Co., which owned the NC&I, built a railroad branch connecting the No. 1, 2 and 3 collieries to the Lackawanna & Bloomsburg Railroad. By 1872, the shaft was 295 feet (90 m) deep and 130 men were working in the Lance and Cooper veins.[54] As of 1914, the Delaware & Hudson continued to operate the mine, dumping waste water into the creek.[22]

Delaware & Hudson No. 2 Colliery

The Northern Coal & Iron Co. built the No. 2 shaft on the north side of Shupp's Creek, west of Nesbitt Street or about 650 feet (200 m) east of the No. 1 shaft. By 1872, the shaft was 500 feet (150 m) deep reaching the Lawler and Wilkman coal veins.[54] By 1873, the NC&I operated a breaker at the shaft. As of 1914, the Delaware & Hudson Canal Co. was operating a breaker and washery there, dumping waste water into Shupp's Creek.[22]

Delaware & Hudson No. 3 Colliery

The No. 3 Colliery was located along Shupp's creek about a mile east of the No. 2 Colliery. By 1872, a contractor, T.C. Harkness, had sunk the shaft 350 feet (110 m) and was driving a tunnel toward the Boston Mine to create a second means of egress.[86] By 1873, the Northern Coal & Iron Co. operated a breaker on the site.

By the year 1893, the Delaware & Hudson Canal Co. was operating the colliery, producing 219,044 tons of coal. However, on November 15, 1894, the first No.3 breaker burned. The headline in the Wilkes-Barre Times read, "A glorious scene – the whole valley lighted up and glare seen in Scranton – will be re-built at once."[87] In January 1895, the new breaker at the No. 3 was under construction,[88] designed by Abram Shaffer; it began operating on June 1, 1895. According to the newspapers, it was clad in corrugated iron and had a "fine appearance."[89] By 1916, the Delaware & Hudson decided to abandon the No. 3 breaker and run coal from the mine through the company's No. 5 breaker, and on the morning of December 2, the No. 3 breaker was destroyed by fire.

Kingston Coal Company Mines

In 1864, Waterman & Beaver Co., owned by industrialists from Danville, Pennsylvania, sank the No. 1 shaft in Kingston, known as "Morgan's Shaft" after superintendent David Morgan. In 1868, Daniel Edwards, superintendent of W&B's Danville iron mines, replaced Morgan as superintendent. The firm's coal lands spanned the boundary between Plymouth and Kingston townships, and in 1872, the No. 2 shaft and the No. 2 breaker were constructed, both in Plymouth. A railroad branch connected the No. 2 colliery to the Lackawanna & Bloomsburg Railroad. In 1877, the firm's name was changed to Kingston Coal Company.[29] The Plymouth side of the colliery became part of Edwardsville when it was incorporated as a separate borough on June 16, 1884.

Woodward Colliery

The Woodward Colliery was located on the eastern slope of Ross Hill up-hill from Toby's Creek. With 925 acres (3.74 km2) of coal lands, it was a major colliery, and the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad took several years to establish it. In 1881, in what was then Plymouth Township, the DL&W began to sink two shafts, the largest of which (at 22 X 55 feet) was sunk 1,000 feet (300 m) to the Red Ash coal vein.[90] By 1883, the DL&W had begun to construct a breaker and to prepare railroad beds for a branch line connecting the breaker to the DL&W's railroad line on the west shore of the Susquehanna River. In September 1883, four men working on the shaft were killed when the platform supporting them collapsed.[91] In 1884, the colliery became part of the newly formed Edwardsville Borough. By 1888, the colliery was complete, and in July the Woodward began to ship coal.[92] The new mine and breaker had a large capacity: in May 1904, the colliery broke a record, producing 77,383 tons of coal.[93]

In July 1916, the DL&W announced plans to build a new concrete breaker, and to fill in part of Toby's Creek so as to straighten the railroad bed leading to the breaker.[94] By 1917, the new breaker was under construction. The foundation was built by Curtis Construction Co. of New York, and the steel frame built by the DL&W. The facade of the breaker was clad with special high-strength wire glass. The new colliery had its own power plant fueled by coal from the mine.[95] In 1936, the Glen Alden Coal Co., successor to the DL&W, operated the Woodward and produced 858,711 tons of coal. In 1945, they produced 745,586 tons. The Woodward coal breaker closed for business on October 14, 1961.[96]

See also

References

- ^ Baltimore Patriot, May 12, 1830.

- ^ Petrillo, F. Charles (1986). Anthracite and Slackwater, The North Branch Canal 1828–1901. Easton, Pennsylvania: Harmony Press. ISBN 978-0930973049..

- ^ a b c d Samuel Livingston French, Reminiscences of Plymouth, Luzerne County, Penna. (New York: Lotus Press, 1915).

- ^ E.O. Jameson, The Jamesons in America, 1647–1900 (Boston: The Rumford Press, 1901).

- ^ a b c Hendrick B. Wright, Historical Sketches of Plymouth, Luzerne Co., Penna. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: T.B. Peterson & Brothers, 1873).

- ^ a b P. Frazer Smith, Pennsylvania State Reports, vol. LV (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Kay & Brother, 1868).

- ^ a b c d e Samuel H. Daddow and Benjamin Bannan, Coal Iron and Oil (Pottsville, Pennsylvania: Benjamin Bannan, 1866).

- ^ a b c d Reports of the Inspectors of Coal Mines...for the year 1871 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, 1872).

- ^ The Wilkes-Barre Record, September 26, 1935, page 13.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Daily, August 1, 1872, p.3.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Weekly Times (Wilkes-Barre, PA), July 7, 1900, page 8, column 3.

- ^ Samuel Robert Smith, The Black Trail of Anthracite (Kingston, Pennsylvania: S.R. Smith, 1907).

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Record, May 17, 1901, page 8.

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Mines...for the Year 1871 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Benjamin Singerly, 1872),294.

- ^ New York Herald, December 6, 1875.

- ^ Frederick E. Saward, The Coal Mines of Pennsylvania (New York: 1880).

- ^ Index to Executive Documents.

- ^ A Dictionary of Arts, Science and General Literature, vol. II (New York: Henry G. Allen Co., 1891).

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Mines...for the Year 1896 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Clarence M.Busch, 1897).

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Weekly Times (Wilkes-Barre, PA), July 7, 1900, page 8, columns 2-3.

- ^ Oscar J. Harvey and Ernest Gray Smith, A History of Wilkes-Barre, vol. V (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: self-published, 1930).

- ^ a b c d e f Water Supply Commission of Pennsylvania, Water Resources Inventory Report, Part X (Harrisburg PA: Wm. Stanley Ray, 1917).

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, August 26, 1919.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, January 29, 1923.

- ^ Sunday Independent, December 27, 1936.

- ^ The Wilkes-Barre Record, August 18, 1941, page 13.

- ^ History of Delaware County and Ohio (Chicago: O.L. Baskin & Co., 1880).

- ^ Daniel Hodas, The Business Career of Moses Taylor (New York: New York University Press, 1976).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j W.W. Munsell & Co., History of Luzerne, Lackawanna and Wyoming Counties, Pa. (New York: W.W. Munsell & Co., 1880).

- ^ Sunday Independent, February 10, 1935,

- ^ Sunday Independent, December 29, 1940.

- ^ a b 1955 Annual Report, Anthracite Division, Pennsylvania Department of Mines and Mineral Industries.

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Coal Mines...for the year 1871(Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, 1872).

- ^ Sunday Independent, March 15, 1942.

- ^ Connecticut Journal, June 14, 1804.

- ^ Springfield Republican, December 27, 1901.

- ^ Journal of the House of Representatives, Volume I, 1826-1827, page 203.

- ^ The Register of Pennsylvania, Samuel Hazard, ed., November 13, 1830.

- ^ Wyoming Republican and Herald, July 8, 1835, page 3.

- ^ a b Hendrick B. Wright, Historical Sketches of Plymouth, 1873, page 327.

- ^ Benjamin Silliman, "Notice of the Anthracite Region", in The Register of Pennsylvania, ed. Samuel Hazard, vol. 6 (Philadelphia: Wm. F. Geddes, 1831), 70-77.

- ^ George W. Harris, Pennsylvania State Reports, v.23 (Philadelphia: T.K. & P.G. Collins, 1855).

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times, March 27, 1912.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, February 12, 1916.

- ^ Sunday Independent, August 30, 1936.

- ^ Sunday Independent, September 20, 1936.

- ^ Sunday Independent, February 5, 1939.

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Mines...for the year 1884 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Lane S. Hart, 1885).

- ^ Engineering and Mining Journal, September 20, 1884.

- ^ a b Reports of the Inspectors of Mines...for the year 1887 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Edwin K. Meyers, 1888).

- ^ Sunday Independent, June 29, 1914.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, July 14, 1920.

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Coal Mines...for the year 1870 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, 1871).

- ^ a b c Reports of the Inspectors of Mines...for the year 1872 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Benjamin Singerly, 1873).

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times, October 24, 1878.

- ^ New York Times, December 21, 1914.

- ^ Philadelphia Inquirer, March 5, 1900.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, January 27, 1915.

- ^ Henry Darwin Rogers, The Geology of Pennsylvania, vol. 2 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1858)

- ^ a b Lemuel Amerman, Pennsylvania State Reports, vol. 2 (New York: Banks & Brothers, 1886).

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Coal Mines ... for the year 1871(Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, 1872).

- ^ The Engineering and Mining Journal, April 19, 1879.

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Coal Mines...for the year 1883 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Lane S. Hart, 1884).

- ^ The Coal Trade Journal, March 7, 1883, page 153.

- ^ Sunday Independent, September 28, 1941.

- ^ Cincinnati Daily Gazette, March 6, 1879,

- ^ Record of the Times, page 4, June 11, 1879.

- ^ Engineering and Mining Journal, vol. 28 (New York: The Scientific Publishing Co., 1879).

- ^ Sunday Independent, May 19, 1935.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Record, June 17, 1935.

- ^ Sunday Independent, December 29, 1940, p.C-6.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times, November 7, 1906.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times, August 29, 1907.

- ^ a b c Water Supply Commission of Pennsylvania, Water Resources Inventory Report, Part X (Harrisburg PA: Wm. Stanley Ray, 1917).

- ^ Report of the Dept. of Mines of Pennsylvania (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: J.L.L. Kuhn, 1919).

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times, April 29, 1907.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times, January 22, 1919.

- ^ !965 Annual Report, Anthracite Division, Pennsylvania Department of Mines and Mineral Industries.

- ^ a b P. Frazier Smith, Pennsylvania State Reports (Philadelphia; Kay & Brother, 1868).

- ^ F.C. Johnson, ed., The Historical Record, vol. 1 (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: Press of the Wilkes-Barre Record, 1887).

- ^ New York Herald Tribune, January 17, 1857.

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Mines...for the Year 1871 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, 1872), 294.

- ^ Frederick E. Saward, The Coal Trade (New York: 1884.)

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Mines...for the Year 1887 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Edwin K. Meyers, 1888).

- ^ Report of the Department of Mines of Pennsylvania, 1909 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: C.E. Aughinbaugh, 1910).

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Mines...for the year 1872 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Benjamin Singerly, 1873).

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times, November 16, 1894.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times, January 8, 1895.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times, May 25, 1895.

- ^ Philadelphia Inquirer, November 15, 1886.

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Mines...for the year 1883 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Lane S. Hart, 1884).

- ^ Reports of the Inspectors of Mines...for the year 1888 (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Edwin K. Meyers, 1889).

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times, June 2, 1904.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, July 10, 1916.

- ^ Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, August 17, 1917.

- ^ 1961 Annual Report, Anthracite Division, Pennsylvania Department of Mines and Mineral Industries