Jeremy Clarkson

Jeremy Clarkson | |

|---|---|

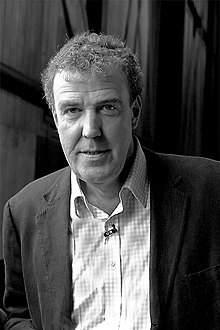

Clarkson in 2012 | |

| Born | Jeremy Charles Robert Clarkson[1] 11 April 1960[1] |

| Nationality | British |

| Other names | Jezza |

| Education | Hill House School, Doncaster Repton School |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, presenter, columnist, writer, farmer |

| Years active | 1988–present |

| Employers | BBC 1988–2015 |

| Known for |

|

| Notable work | See below |

| Height | 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m)[2] |

| Spouses |

|

| Partner | Lisa Hogan (2017–present) |

| Children | 3 |

Jeremy Charles Robert Clarkson (born 11 April 1960) is an English broadcaster, journalist, farmer, game show host and writer who specialises in motoring. He is best known for the motoring programmes Top Gear and The Grand Tour alongside Richard Hammond and James May. He also currently writes weekly columns for The Sunday Times and The Sun. Since 2018, Clarkson has hosted the revived ITV game show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, replacing former host Chris Tarrant.

From a career as a local journalist in northern England, Clarkson rose to public prominence as a presenter of the original format of Top Gear in 1988. Since the mid-1990s, he has become a recognised public personality, regularly appearing on British television presenting his own shows for BBC and appearing as a guest on other shows. As well as motoring, Clarkson has produced programmes and books on subjects such as history and engineering. In 1998, he hosted the first series of Robot Wars, and from 1998 to 2000 he also hosted his own talk show, Clarkson.

In 2015, the BBC decided not to renew Clarkson's contract with the company after an assault on a Top Gear producer while filming on location.[3][4] That year, Clarkson and his Top Gear co-presenters and producer Andy Wilman formed the production company W. Chump & Sons to produce The Grand Tour for Amazon Prime Video.

His opinionated but humorous tongue-in-cheek writing and presenting style has often provoked a public reaction. His actions, both privately and as a Top Gear presenter, have also sometimes resulted in criticism from the media, politicians, pressure groups and the public. He also has a significant public following, being credited as a major factor in the resurgence of Top Gear as one of the most popular shows on the BBC.

Early life

Childhood

Clarkson was born in Doncaster, West Riding of Yorkshire, the son of Shirley Gabrielle Clarkson (1934–2014), a teacher,[5] and Edward Grenville Clarkson (1932–1994), a travelling salesman.[6] His parents, who ran a business selling tea cosies, put their son's name down in advance for private schools, with no idea how they were going to pay the fees. However, shortly before his admission, when he was 13, his parents made two Paddington Bear stuffed toys for Clarkson and his sister Joanna.[7] These proved so popular that they started selling them through the business.[8] Because they were manufacturing and selling the bears without regard to intellectual property rights, upon his becoming aware of the bears Michael Bond took action through his solicitors. Edward Clarkson travelled to London to meet Bond's lawyer. By coincidence, he met Bond in the lift, and the two struck up an immediate rapport. Consequently, Bond awarded the Clarksons the licensing of the bear rights throughout the world, with the family eventually selling to Britain's then leading toystore, Hamleys.[9] The income from this success enabled the Clarksons to be able to pay the fees for Jeremy to attend Hill House School, Doncaster, and later Repton School.[8]

Repton School

Clarkson has stated he was deeply unhappy at Repton School, saying that he had been a "suicidal wreck" there, having experienced extreme bullying. He alleged that:

I suffered many terrible things. I was thrown on an hourly basis into the ice plunge pool, dragged from my bed in the middle of the night and beaten, made to lick the lavatories clean and all the usual humiliations that... turn a small boy into a gibbering, sobbing, suicidal wreck... they glued my records together, snapped my compass, ate my biscuits, defecated in my tuck box and they cut my trousers in half.[10]

According to his own account, he was expelled from Repton School for "drinking, smoking and generally making a nuisance of himself."[11] He famously left with one C and two U (fail) grades at A level.[12] Clarkson attended Repton alongside Formula One engineer Adrian Newey[13] and former Top Gear Executive Producer Andy Wilman.

He played the role of a public schoolboy, Atkinson, in a BBC radio Children's Hour serial adaptation of Anthony Buckeridge's Jennings novels until his voice broke.[14][15]

Career

Writing career

Clarkson's first job was as a travelling salesman for his parents' business, selling Paddington Bear toys.[16] He later trained as a journalist with the Rotherham Advertiser, before also writing for the Rochdale Observer, Wolverhampton Express and Star, Lincolnshire Life, Shropshire Star and the Associated Kent Newspapers.

When writing in 2015 in his final column for Top Gear magazine, he credited the Shropshire Star as his first outlet as a motoring columnist: "I started small, on the Shropshire Star with little Peugeots and Fiats and worked my way up to Ford Granadas and Rovers until, after about seven years, I was allowed to drive an Aston Martin Lagonda... It was 10 years before I drove my first Lamborghini."[17]

In 1984, Clarkson formed the Motoring Press Agency (MPA), in which, with fellow motoring journalist Jonathan Gill, he conducted road tests for local newspapers and automotive magazines. This developed into articles for publications such as Performance Car.[18] He has regularly written for Top Gear magazine since its launch in 1993.

In 1987, Clarkson wrote for Amstrad Computer User and compiled Amstrad CPC game reviews.[19]

Clarkson writes regular columns in the tabloid newspaper The Sun, and for the broadsheet newspaper The Sunday Times. His columns in the Times are republished in The Weekend Australian newspaper. He also writes for the "Wheels" section of the Toronto Star. He has written humorous books about cars and several other subjects, with many of his books being collections of articles that he has written for The Sunday Times.

Television

Clarkson's first major television role came as one of the presenters on the British motoring programme Top Gear, from 27 October 1988 to 3 February 2000,[20] in the programme's earlier format. Jon Bentley, a researcher at Top Gear, helped launch his television career.[21] Bentley shortly afterwards became the show's producer, and said about hiring Clarkson:

"He was just what I was looking for – an enthusiastic motoring writer who could make cars on telly fun. He was opinionated and irreverent, rather than respectfully po-faced. The fact that he looked and sounded exactly like a twenty-something ex-public schoolboy didn't matter. Nor did the impression there was a hint of school bully about him. I knew he was the man for the job. [...] Clarkson stood out because he was funny. Even my bosses allowed themselves the odd titter."[22]

Clarkson then also presented the show's new format from 20 October 2002 to 8 March 2015.[23] Along with co-presenters James May and Richard Hammond, he is credited with turning Top Gear into the most-watched TV show on BBC Two,[24] rebroadcast to over 100 countries around the world.[25] Clarkson's company Bedder 6, which handled merchandise and international distribution for Top Gear, earned over £149m in revenue in 2012, prior to a restructuring that gave BBC Worldwide full control of the Top Gear rights.[26][27]

Clarkson presented the first series UK version of Robot Wars.[28] His talk show, Clarkson, comprised 27 half-hour episodes aired in the United Kingdom between November 1998 and December 2000, and featured guest interviews with musicians, politicians and television personalities. Clarkson went on to present documentaries focused on non-motoring themes such as history and engineering, although the motoring shows and videos continued. Alongside his stand-alone shows, many mirror the format of his newspaper columns and books, combining his love of driving and motoring journalism, with the examination and expression of his other views on the world, such as in Jeremy Clarkson's Motorworld, Jeremy Clarkson's Car Years and Jeremy Clarkson Meets the Neighbours.

After Trinny and Susannah labelled Clarkson's dress sense as that of a market trader, he was persuaded to appear on their fashion makeover show What Not to Wear to avoid being considered for their all-time worst dressed winner award.[29] Their attempts at restyling Clarkson were rebuffed, and Clarkson stated he would rather eat his own hair than appear on the show again.[30][31]

For an episode of the first series of the BBC's Who Do You Think You Are? broadcast in November 2004, Clarkson was invited to investigate his family history. It included the story of his great-great-great grandfather, John Kilner (1792–1857), who invented the Kilner jar, a container for preserved fruit.[32][33]

Clarkson's views are often showcased on television shows. In 1997, Clarkson appeared on the light-hearted comedy show Room 101, in which a guest nominates things they hate in life to be consigned to nothingness. Clarkson dispatched caravans, houseflies, the sitcom Last of the Summer Wine, the mentality within golf clubs, and vegetarians. He has made several appearances on the prime time talk shows Parkinson and Friday Night with Jonathan Ross since 2002. By 2003, his persona was deemed to fit the mould for the series Grumpy Old Men, in which middle-aged men talk about any aspects of modern life which irritate them. Since the topical news panel show Have I Got News for You dismissed regular host Angus Deayton in October 2002, Clarkson has become one of the most regularly used guest hosts on the show. Clarkson has appeared as a panellist on the political current affairs television show Question Time twice since 2000. On 2 October 2015, he presented Have I Got News for You again for the first time since his dismissal.[34]

Clarkson received a BAFTA nomination for Best Entertainment Performance in 2006. Jonathan Ross ended up winning the award.[35] He won the National Television Awards Special Recognition Award in 2007, and reportedly earned £1 million that same year for his role as a Top Gear presenter, and a further £1.7 million from books, DVDs and newspaper columns.[36] Clarkson and co-presenter James May were the first people to reach the North Magnetic Pole in a car also in 2007, chronicled in Top Gear: Polar Special.[37]

He sustained minor injuries to his legs, back and hand in an intentional collision with a brick wall while making the 12th series of Top Gear in 2008.[38]

In 2014, he received a £4.8 million dividend and an £8.4 million share buyout from BBC Worldwide, bringing his estimated income for the year to more than £14 million.[39]

On 30 July 2015, it was announced that Clarkson, along with former Top Gear hosts Richard Hammond and James May would present a new show on Amazon Prime Video. The first season was made available worldwide in 2016.[40][41] On 11 May 2016, Clarkson confirmed on his Twitter feed that the series would be titled The Grand Tour, and air from a different location each week.[42]

On 9 March 2018, it was announced that Clarkson would host a revamped series of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? on ITV. The show had previously been presented by Chris Tarrant.[43]

Opinions and influence

Politics

Clarkson is in favour of personal freedom and against government regulation, stating that government should "build park benches and that is it. They should leave us alone."[44] He has a particular contempt for the Health and Safety Executive. He often criticised the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, especially what he calls the "ban" culture, frequently fixating on the bans on smoking and 2004 ban on fox hunting. In April 2013, Clarkson was among 2,000 invited guests to the funeral of Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.[45]

In an attempt to prove that the public furore over the 2007 UK child benefit data scandal was unjustified, he published his own bank account number and sort code, together with instructions on how to find out his address, in The Sun newspaper, expecting nobody to be able to remove money from his account. He later discovered that someone had set up a monthly direct debit for £500 to Diabetes UK.[46]

Clarkson supported a Remain vote in the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum.[47][48] Clarkson does not support Brexit, stating that while the European Union has its problems, Britain would not have any influence over the EU, should it leave the Union. He envisions the European Union being turned into a US-like "United States of Europe", with one army, one currency, and one unifying set of values.[49] In 2019, Clarkson said: "Europe has to punish us—they can’t allow us to leave without being damaged because then everyone will want to go. We don’t want to go if we’re going to be damaged."[48]

Clarkson's comments have both a large number of supporters and opponents. He often comments on the media-perceived social issues of the day, such as the fear of challenging adolescent youths, known as "hoodies". In 2007, Clarkson was cleared of allegations of assaulting a hoodie while visiting central Milton Keynes, after Thames Valley Police said that if anything, he had been the victim.[50] In the five-part series Jeremy Clarkson: Meets the Neighbours he travelled around Europe in a Jaguar E-Type, examining (and in some cases reinforcing) his stereotypes of other countries.

As a motoring journalist, he is frequently critical of government initiatives such as the London congestion charge or proposals on road charging. He is also frequently scornful of caravanners and cyclists. He has often singled out John Prescott, the former Transport Minister, and Stephen Joseph,[51] the head of the public transport pressure group Transport 2000, for ridicule.

In September 2013, a tweet proposing that he might stand for election as an independent candidate in Doncaster North, the constituency of the then Labour leader of the opposition, Ed Miliband, was retweeted over 1,000 times – including by John Prescott.[52]

Clarkson has been critical of the Special Relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom.[53] He referred to the US as the "United States of Total Paranoia", commenting that one needs a permit to do everything except for purchasing weapons.[54] In 2017, in response to the United States officially recognising Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, Clarkson advised Palestinians to recognize London as the capital of the United States.[55]

In 2020, Clarkson stated that he usually votes for the Conservative Party, claiming not to be a natural Tory but "it just happens to be that every time it comes around and you weigh up which is going to provide you with a better life, the better country to live in, then it's usually the Conservatives" and mocked the policies of Tony Blair and Jeremy Corbyn, stating "only an idiot would vote for Corbyn." However, he also expressed support of incumbent Labour leader Keir Starmer and maintained that he was prepared to vote for Labour "if there's an election tomorrow" citing Boris Johnson's handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.[56][57] Clarkson is also a personal friend of former Prime Minister and Conservative leader David Cameron.[58]

Environment

Clarkson is critical of the green movement and environmentalism, including groups such as Greenpeace—he has called them "eco-mentalists" and "old trade unionists and CND lesbians"[59] but has also said that, although he "hate[s] the movement, [he] loves the destination" of environmentalism and believes that people should quietly strive to be more eco-friendly.[60] He has been dismissive of windfarms and said they will be described as "a reminder of the time when mankind temporarily took leave of its senses and decided wind, waves and lashings of tofu could somehow generate enough electricity for the whole planet".[61][better source needed] Clarkson has spoken in support of hydrogen cars.[44]

Clarkson rejects the scientific consensus on climate change, believing that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions do not affect the global climate.[60] He has also expressed doubt that the effects of climate change are "a bad thing",[60] saying in 2005 "let's just stop and think for a moment what the consequences might be. Switzerland loses its skiing resorts? The beach in Miami is washed away? North Carolina gets knocked over by a hurricane? Anything bothering you yet?"[62] However, during a 2019 trip to Cambodia while filming The Grand Tour, Clarkson acknowledged the "graphic demonstration" of climate change impacts on the Mekong River and Tonlé Sap was "genuinely alarming", but still expressed doubt that it was driven by human activity. Cambodia was undergoing a severe drought during the show's filming.[63][64] Clarkson is against climate activism,[65] and has often made personal attacks against teenage activist Greta Thunberg, whom he has called "a spoilt brat".[66][67]

Environmentalists have protested or heckled Clarkson on a number of occasions for his views, including at his honorary degree ceremony at Oxford Brookes University, where a protester threw a banana meringue pie in his face in 2006, and in 2009 when activist group Climate Rush dumped horse manure on his lawn.[68][69] Clarkson's comments on Greta Thunberg were criticized by his own daughter.[66]

Himself

Whilst Clarkson states such views in his columns and in public appearances, his public persona does not necessarily represent his personal views, as he acknowledged whilst interviewing Alastair Campbell, saying "I don't believe what I write, any more than you [Campbell] believe what you say".[70]

Clarkson has been described as a "skillful propagandist for the motoring lobby" by The Economist.[71] With a forthright and sometimes deadpan delivery, Clarkson is said to thrive on the notoriety his public comments bring, and has risen to the level of the bête noire of the various groups who disagree with his views. On the Channel 4-organised viewer poll, for the 100 Worst Britons We Love to Hate programme, Clarkson polled in 66th place. By 2005, Clarkson was perceived by the press to have upset so many people and groups, The Independent put him on trial for various "crimes", declaring him guilty on most counts.[62]

Media

Responses to Clarkson's comments are often directed personally, with derogatory comments about residents of Norfolk leading to some residents organising a "We hate Jeremy Clarkson" club. In The Guardian's 2007 'Media 100' list, which lists the top 100 most "powerful people in the [media] industry", based on cultural, economic and political influence in the UK, Clarkson was listed as a new entrant at 74th. Some critics even attribute Clarkson's actions and views as being influential enough to be responsible for the closure of Rover and the Luton manufacturing plant of Vauxhall.[72] Clarkson's comments about Rover prompted workers to hang an "Anti-Clarkson Campaign" banner outside the defunct Longbridge plant in its last days.

The BBC often played down his comments as ultimately not having the weight they were ascribed. In 2007, they described Clarkson as "Not a man given to considered opinion",[33] and in response to an official complaint another BBC spokeswoman once said: "Jeremy's colourful comments are always entertaining, but they are his own comments and not those of the BBC. More often than not they are said with a twinkle in his eye."[73]

On his chat show, Clarkson, he caused upset to the Welsh by placing a 3D plastic map of Wales into a microwave oven and switching it on. He later defended this by saying, "I put Wales in there because Scotland wouldn't fit."[74][75][76]

Recognition

In 2005, Clarkson received an honorary Doctor of Engineering degree from the Oxford Brookes University.[77] His views on the environment precipitated a small demonstration at the award ceremony for his honorary degree, when Clarkson was pied by road protester Rebecca Lush.[68] Clarkson took this incident in good humour, responding 'good shot' and subsequently referring to Lush as "Banana girl".[78]

In 2008, an internet petition was posted on the Prime Minister's Number 10 website to "Make Jeremy Clarkson Prime Minister". By the time it closed, it had attracted 49,446 signatures. An opposing petition posted on the same site set to "Never, Ever Make Jeremy Clarkson Prime Minister" attracted 87 signatures. Clarkson later commented he would be a rubbish Prime Minister as he is always contradicting himself in his columns.[44] In their official response to the petition, Number 10 agreed with Clarkson's comments.[79]

In response to the reactions he gets, Clarkson has stated "I enjoy this back and forth, it makes the world go round but it is just opinion."[44] On the opinion that his views are influential enough to topple car companies, he has argued that he has proof that he has had no influence. "When I said that the Ford Orion was the worst car ever it went on to become a best-selling car."[44]

Clarkson was ranked 49th on Motor Trend Magazine's Power List for 2011, its list of the fifty most influential figures in the automotive industry.[80]

Other interests

Military interests

Clarkson has a keen interest in the British Armed Forces and several of his DVDs and television shows have featured a military theme, such as flying in military jets or several Clarkson-focused Top Gear spots having a military theme such as Clarkson escaping a Challenger 2 tank in a Range Rover, a Lotus Exige evading missile lock from an Apache attack helicopter, a platoon of Irish Guardsmen shooting at a Porsche Boxster and Mercedes-Benz SLK, or using a Ford Fiesta as a Royal Marine landing craft. In October 2005, Clarkson visited British troops in Baghdad.[81]

In 2003, Clarkson presented The Victoria Cross: For Valour, looking at recipients of the Victoria Cross, in particular focusing on his father-in-law, Robert Henry Cain, who received a VC for actions during the Battle of Arnhem in World War II.[82]

In 2007, Clarkson wrote and presented Jeremy Clarkson: Greatest Raid of All Time, a documentary about the World War II Operation Chariot, a 1942 Commando raid on the docks of Saint-Nazaire in occupied France. At the end of 2007, Clarkson became a patron of Help for Heroes,[83] a charity aiming to raise money to provide better facilities to wounded British servicemen. His effort led to the 2007 Christmas appeal in The Sunday Times supporting Help for Heroes.[84]

Engineering interests

Clarkson is passionate about engineering, especially pioneering work. In Inventions That Changed the World Clarkson showcased the invention of the gun, computer, jet engine, telephone and television. He has previously criticised the engineering feats of the 20th century as merely improvements on the truly innovative inventions of the Industrial Revolution. He cites the lack of any source of alternative power for cars, other than by "small explosions". In Great Britons, as part of a public poll to find the greatest historical Briton, Clarkson was the chief supporter for Isambard Kingdom Brunel, a prominent engineer during the Industrial Revolution credited with numerous innovations. Despite this, he also has a passion for many modern examples of engineering. In Speed and Extreme Machines, Clarkson rides and showcases numerous vehicles and machinery. Clarkson was awarded an honorary degree from Brunel University on 12 September 2003, partly because of his work in popularising engineering, and partly because of his advocacy of Brunel.[85]

In his book I Know You Got Soul, he describes many machines that he believes possess a soul. He cited the Concorde crash as his inspiration, feeling a sadness for the demise of the machine as well as the passengers. Clarkson was a passenger on the last BA Concorde flight, on 24 October 2003. Paraphrasing Neil Armstrong he described the retirement of the fleet as "This is one small step for a man, but one huge leap backwards for mankind".[86]

He briefly acquired an English Electric Lightning F1A jet fighter XM172, which was installed in the front garden of his country home. The Lightning was subsequently removed on the orders of the local council, which "wouldn't believe my claim that it was a leaf blower", according to Clarkson on a Tiscali Motoring webchat. The whole affair was set up for his programme Speed, and the Lightning is now back serving as gate guardian at Wycombe Air Park (formerly RAF Booker).[87]

In a Top Gear episode, Clarkson drove the Bugatti Veyron in a race across Europe against a Cessna private aeroplane. The Veyron was an £850,000 technology demonstrator project built by Volkswagen to become the fastest production car, but a practical road car at the same time. In building such an ambitious machine, Clarkson described the project as "a triumph for lunacy over common sense, a triumph for man over nature and a triumph for Volkswagen over absolutely every other car maker in the world."[88] After winning the race, Clarkson announced that "It's quite a hollow victory really, because I've got to go for the rest of my life knowing that I'll never own that car. I'll never experience that power again."[89]

Cars

Ownership

Cars Clarkson currently owns:

- Range Rover Autobiography V8[90]

- Mercedes-Benz 600 Grosser[91]

- Range Rover TDV8 Vogue SE[92]

- Jeep Wrangler[93]

- Alfa Romeo Alfetta GTV6[94]

- Range Rover Vogue SE[95]

- Bentley Flying Spur[96]

Cars Clarkson has owned:

- Ford Cortina[94]

- Volkswagen Scirocco 1[97]

- Volkswagen Scirocco 2[97]

- Honda CR-X[98]

- BMW 3.0L CSL[98]

- BMW Z1[99]

- Ford Escort RS Cosworth[100][101]

- Ferrari F355[98]

- Toyota Land Cruiser[102]

- Jaguar XJR[94]

- Mercedes-Benz SL55 AMG[103]

- Volvo XC90[104]

- Lotus Elise 111S[105]

- Ford GT[106]

- Ford Focus[107]

- Mercedes-Benz SLK55 AMG[108]

- Lamborghini Gallardo Spyder[98]

- Aston Martin V8 Vantage[98]

- Mercedes CLK63 AMG Black[98]

- Mercedes-Benz CL 600[109]

- Volkswagen Golf GTI[110]

- Modified Bentley Continental GT V8[111]

Clarkson wanted to purchase the Ford GT after admiring its inspiration, the Ford GT40 race cars of the 1960s. Clarkson was able to secure a place on the shortlist for the few cars that would be imported to Britain to official customers, only through knowing Ford's head of PR through a previous job. After waiting years and facing an increased price, he found many technical problems with the car. After "the most miserable month's motoring possible," he returned it to Ford for a full refund. After a short period, including asking Top Gear fans for advice over the Internet, he bought back his GT. He called it "the most unreliable car ever made", because he was never able to complete a return journey with it.[106] In 2006, Clarkson ordered a Gallardo Spyder and sold the Ford GT to make way for it. In August 2008, he sold the Gallardo because "idiots in Peugeots kept trying to race [him] in it".[112] In October, he announced that he had sold his Volvo XC90. In January 2009, in a review of the car printed in The Times, he wrote: "I’ve just bought my third Volvo XC90 in a row and the simple fact is this: it takes six children to school in the morning."[104]

Likes

You can't be a true petrolhead until you've owned an Alfa Romeo.

— Jeremy Clarkson

Clarkson has spoken highly of the Czech-made Škoda Yeti, calling it possibly the best car in the world, and used 20 minutes of a Top Gear episode putting the Yeti through a number of challenges to support his point.[113] Clarkson called the Brera, Alfa's latest sports car, "Cameron Diaz on wheels".[114] Clarkson has expressed fondness for late-model V8 Holdens, available in the UK rebadged as Vauxhalls. Of the Monaro he said, "It's like they had a picture of me on their desk and said [Australian accent] 'Let's build that bloke a car!'" and "I can't believe it... I've fallen in love... with a Vauxhall!"[115] Clarkson suffered two slipped discs that he attributed to driving the Monaro, which he described as being "back-breakingly marvellous".[116] Clarkson considers the Lexus LFA as the best car he has ever driven.[117]

Dislikes

Clarkson dislikes the British car brand Rover, the last major British owned and built car manufacturer. This view stretched back to the company's time as part of British Leyland. Describing the history of the company up to its last flagship model, the Rover 75, he paraphrased Winston Churchill and stated "Never in the field of human endeavour has so much been done, so badly, by so many," citing issues with the rack and pinion steering system. In the latter years of the company, Clarkson blamed the "uncool" brand image as being more of a hindrance to sales than any faults with the cars. On its demise, Clarkson stated "I cannot even get teary and emotional about the demise of the company itself – though I do feel sorry for the workforce." Clarkson has also expressed hatred for the Toyota Prius.[118]

Clarkson has also criticised Vauxhalls[119][120] and has described Vauxhall's parent company, General Motors, as a "pensions and healthcare" company which sees the "car making side of the business as an expensive loss-making nuisance".[120] Clarkson has expressed particular disdain for the Vauxhall Vectra, describing it as:

"One of my least favourite cars in the world. I've always hated it because I've always felt it was designed in a coffee break by people who couldn't care less about cars" and "one of the worst chassis I've ever come across."[121]

After a Top Gear piece by Clarkson for its launch in 1995, described by The Independent as "not doing [GM] any favours",[122] Vauxhall complained to the BBC and announced, "We can take criticism but this piece was totally unbalanced."[123]

Controversies

Clarkson's comments and actions have sometimes resulted in complaints from viewers, car companies, and national governments.

Activities on Top Gear

In 2004, the BBC apologised unreservedly and paid £250 in compensation to a Somerset parish council, after Clarkson damaged a 30-year-old horse-chestnut tree by driving into it to test the strength of a Toyota Hilux.[124] In December 2006, the BBC complaints department upheld the complaint of four Top Gear viewers that Clarkson had used the phrase "ginger beer" (rhyming slang for "queer") in a derogatory manner, when Clarkson picked up on and agreed with an audience member's description of the Daihatsu Copen as being a bit "gay".[125] The Top Gear: Polar Special was criticised by the BBC Trust for glamorising drunk driving in a scene showing Clarkson and James May in a vehicle, despite Clarkson saying to the camera, "And please do not write to us about drinking and driving, because I am not driving I am sailing" (as they were on top of international, frozen waters).[126] They stated the scene "was not editorially justified" despite occurring outside the jurisdiction of any drunk-driving laws.

In a later incident during a Top Gear episode broadcast on 13 November 2005, Clarkson, while talking about a Mini design that might be "quintessentially German", made a mock Nazi salute, and made references to the Hitler regime and the German invasion of Poland by suggesting the GPS "only goes to Poland".[127]

In November 2008, Clarkson attracted over 500 complaints to the BBC when he joked about lorry drivers murdering prostitutes.[128][129] The BBC stated the comment was a comic rebuttal of a common misconception about lorry drivers and was within the viewer's expectation of Clarkson's Top Gear persona.[128] Chris Mole, the Member of Parliament for Ipswich, where five prostitutes were murdered in 2006, wrote a "strongly worded" letter to BBC Director-General Mark Thompson, demanding that Clarkson be sacked.[129] Clarkson dismissed Mole's comments in his Sunday Times column the following weekend, writing, "There are more important things to worry about than what some balding and irrelevant middle-aged man might have said on a crappy BBC2 motoring show."[130] Andrew Tinkler, chief executive of the Eddie Stobart Group, a major trucking company, stated that "They were just having a laugh. It's the 21st century, let's get our sense of humour in line."[128]

In July 2009, Clarkson was reported to have called then British Prime Minister Gordon Brown "a silly cunt" during a warm-up while recording a Top Gear show. Although several newspapers reported that he had subsequently argued with BBC Two controller Janice Hadlow,[131] who was present at the recording, the BBC denied that he had been given a "dressing down".[132] John Whittingdale, Conservative chair of the Culture Select Committee remarked: "Many people will find that offensive, many people will find that word in particular very offensive [...] I am surprised he felt it appropriate to use it."[131]

In July 2010, Clarkson reportedly angered gay rights campaigners after he made a remark on Top Gear that did not get aired on the 4 July episode. But guest Alastair Campbell wrote about it on Twitter. Clarkson said: "I demand the right not to be bummed". The BBC later said that they cut this remark out as they "edited down" the interview as it was too long to fit into the show.[133] In an episode aired after the watershed on 1 August 2010, Clarkson described a Ferrari F430 as "special needs". He said the car owned by co-presenter James May looked "like a simpleton". Media regulator Ofcom investigated after receiving two complaints, and found that the comments "were capable of causing offence" but did not censure the BBC.[134]

On 12 January 2012, the Indian High Commission lodged a formal complaint with the BBC over the "tasteless" antics of Clarkson's Top Gear Christmas special where he mocked India's culture and people. During the 90-minute special, which was aired twice over the Christmas break, Clarkson made a string of jokes about Indian food, clothes, toilets, trains and history.[135] On an episode of Top Gear broadcast on 5 February 2012, Clarkson compared a Japanese car/camper van to a person with a growth on their face. A major UK charity that supports people with facial disfigurements, Changing Faces, complained to the BBC and Ofcom after Clarkson's remarks.[136]

In an unused take for a Top Gear feature recorded in early 2012, Clarkson is alleged to have mumbled the ethnic slur "nigger" when repeating the children's rhyme Eeny, meeny, miny, moe. The clip later surfaced on the website of the Daily Mirror tabloid at the beginning of May 2014.[137] In the take, Clarkson attempts to mumble the sentence so as to obscure the word, but admitted that upon a close listening, the word could still be heard. Clarkson apologised for his efforts not being "quite good enough" to ensure the footage was not used.[138] It was reported on 3 May, that the BBC had given Clarkson a final warning, with the presenter accepting that he would be sacked if he made another offensive remark.[139]

Near the end of the Top Gear: Burma Special, which aired March 2014, Clarkson and Hammond were seen admiring a wooden bridge, which they had built during the episode. Clarkson is quoted as saying "That is a proud moment, but there's a slope on it" as a native crosses the bridge, "slope" being a pejorative for Asians. Top Gear Executive Producer Andy Wilman responded: "When we used the word slope in the recent Top Gear Burma Special it was a light-hearted word play joke referencing both the build quality of the bridge and the local Asian man who was crossing it. We were not aware at the time, and it has subsequently been brought to our attention, that the word slope is considered by some to be offensive."[140]

In October 2014, Clarkson attracted controversy when filming the Top Gear: Patagonia Special after driving a Porsche 928 in Argentina with the licence plate H982 FKL, allegedly referring to the 1982 Falklands War.[141] Also, during the broadcast, Clarkson was seen referring to the controversy that had risen after the Burma Special; when inspecting a bridge, which he and his colleagues had built during the episode, he was quoted as saying "That is a proud moment, Hammond, but... is it straight?"[142] With Hammond replying "Yes."

Activities outside Top Gear

In October 1998, Hyundai complained to the BBC about what they described as "bigoted and racist" comments he made at the Birmingham Motor Show, where he was reported as saying that the people working on the Hyundai stand had "eaten a dog" and that the designer of the Hyundai XG had probably eaten a spaniel for his lunch. Clarkson also allegedly referred to those working on the BMW stand as "Nazis", although BMW said they would not be complaining.[73]

In March 2004, at the British Press Awards, he swore at Piers Morgan and punched him before being restrained by security; Morgan says it left him with a scar above his left eyebrow.[143]

In April 2007, he was criticised in the Malaysian parliament for having described one of their cars, the Perodua Kelisa, as the worst in the world, adding that "its name was like a disease and [suggesting] it was built in jungles by people who wear leaves for shoes". A Malaysian government minister countered, pointing out that no complaints had been received from UK customers who had bought the car.[144][145]

In February 2009, while in Australia, Clarkson made disparaging remarks aimed at the British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, calling him a "one-eyed Scottish idiot", and accused him of lying. These comments were widely condemned by the Royal National Institute of Blind People and also Scottish politicians, who requested that he should be taken off air.[146][147][148] He subsequently apologised for referencing Brown's monocular blindness, but insisted: "I haven't apologised for calling him an idiot."[149]

His 4 September 2011 column for The Sun newspaper drew angry remarks[150] in response to Clarkson's call to abolish the Welsh language: "I think we are fast approaching the time when the United Nations should start to think seriously about abolishing other languages. What's the point of Welsh, for example? All it does is provide a silly maypole around which a bunch of hotheads can get all nationalistic." On 30 November 2011, while being interviewed on the BBC's The One Show, Clarkson commented on the UK's public sector strike that day, lauding the capital's empty roads. After mentioning the BBC's need for balance, he said, "I would take them outside and execute them in front of their families." The programme later apologised for his remarks, with further apologies issued by Clarkson and the BBC.[151] These remarks had attracted 21,335 complaints to the BBC within 36 hours; the BBC also received 314 messages of support for Clarkson.[152]

Clarkson was criticised by the mental health charity Mind for his 3 December 2011 column for The Sun, in which he described those who jump in front of trains as "Johnny Suicide" and argues that following a death, trains should carry on their journeys as soon as possible. He adds: "The train cannot be removed nor the line reopened until all of the victim's body has been recovered. And sometimes the head can be half a mile away from the feet." ... "Change the driver, pick up the big bits of what's left of the victim, get the train moving as quickly as possible and let foxy woxy and the birds nibble away at the smaller, gooey parts that are far away or hard to find."[153]

Road safety

Clarkson often discusses high speed driving on public roads, criticising road safety campaigns involving cameras and speed bumps. In 2002, a Welsh Assembly Member Alun Pugh wrote to BBC Director-General Greg Dyke to complain about Clarkson's comments that he believed encouraged people to use Welsh roads as a high-speed test track. A BBC spokesman said that suggestions Clarkson had encouraged speeding were "nonsense".[75] Clarkson has also made similar comments about driving in Lincolnshire.[154] In a November 2005 Times article, Clarkson wrote on the Bugatti Veyron, "On a recent drive across Europe I desperately wanted to reach the top speed but I ran out of road when the needle hit 240 mph," and "From the wheel of a Veyron, France is the size of a small coconut. I cannot tell you how fast I crossed it the other day. Because you simply wouldn't believe me."[155] In 2007, solicitor Nick Freeman represented Clarkson against a charge of driving at 86 mph in a 50 mph zone on the A40 road in London, defeating it on the basis that the driver of the car loaned to Clarkson from Alfa Romeo could not be ascertained.[156] In 2008, Clarkson claimed in a talk at the Hay Festival to have been given a speeding ticket for driving at 186 mph on the A1203 Limehouse Link road in London.[157]

Dismissal from Top Gear

In March 2015, Clarkson was suspended by the BBC from Top Gear following a "fracas" with one of the show's producers.[23] It emerged that Clarkson had been involved in a dispute over catering while filming on location in Hawes, North Yorkshire.[158] Clarkson had been offered soup and a cold meat platter, instead of the steak he wanted, because the hotel chef had gone home.[159]

The BBC announced that the next episode of the show would not be broadcast on 15 March.[23] It was later announced through the BBC's website that the network would be likely to drop the remaining two episodes of the series as well in the wake of the incident, which involved Clarkson punching producer Oisin Tymon, who was later treated in hospital.[160][161] Tymon also claimed that Clarkson had called him a "lazy Irish cunt".[162] Clarkson's contract with the BBC expired at the end of March, and a previously proposed three-year renewal was withdrawn.[163][164][165]

A Change.org petition, aiming to reverse the BBC decision, was started on 10 March by blogger Guido Fawkes.[166][167] The petition reached its target 1,000,000 signatures by the afternoon of 20 March, and was delivered to the BBC in an artillery vehicle by a man dressed as Top Gear test driver The Stig, with Fawkes as spokesman.[168] The hosting website described the petition as the fastest-growing campaign in its history.[169]

On 19 March 2015, at a charity auction at the Roundhouse in Camden, north London, Clarkson launched into a verbal tirade against BBC studio bosses related to his suspension from the programme, saying "The BBC have fucked themselves."[170] He later stated that this was "meant in jest".[171]

On 25 March 2015, the BBC released an official statement confirming that, as a result of the actions which led to his suspension, they would not be renewing his contract with the show.[172] Following the statement, North Yorkshire Police requested to view the report and stated that "action will be taken by North Yorkshire police where necessary".[173] However, Tymon informed the police that he did not wish to press charges against Clarkson, and Clarkson urged fans of the show to stop trolling Tymon on social media, as what happened was not his fault.[174][175] British police investigated death threats made against BBC Director-General Tony Hall over Clarkson's firing.[176] Less than 24 hours after his dismissal, Clarkson was approached by Zvezda, a Russian state broadcaster, to present a motoring programme.[177]

In his Sunday Times column on 19 April, Clarkson revealed that two days before he hit Tymon, he had been told by his doctor that a lump he had could be cancer of the tongue. Testing later confirmed that it was not cancerous. In the same column, he stated that he had initially considered retiring from television following his dismissal, but was now planning a new motoring programme.[178]

In November 2015, Tymon sued Clarkson and the BBC for racial discrimination over the verbal abuse he received in the March incident.[179][180] The following February, Clarkson formally apologised to Tymon and settled the racial discrimination and personal injury claim for £100,000.[162]

Personal life

Clarkson married Alex Hall in 1989, but she left him for one of his friends after six months.[181]

In May 1993, he married his manager, Frances Cain, daughter of VC recipient Robert Henry Cain, in Fulham.[6] The couple lived in Chipping Norton, in the Cotswolds, with their three children.[32] Clarkson has been described as a member of the Chipping Norton set.[182] Known for buying him car-related gifts, for Christmas 2007 Clarkson's second wife bought him a Mercedes-Benz 600.[183] Clarkson and Cain divorced in 2014.[181][184] As of 2017, Clarkson has been in a relationship with Irish born former actress and screenplay writer Lisa Hogan, who features in his Amazon Prime series Clarkson's Farm.[185][186][187]

In September 2010, Clarkson was granted a privacy injunction against his first wife to prevent her from publishing claims that their sexual relationship continued after his second marriage (see AMM v HXW). He voluntarily lifted the injunction in October 2011,[188] commenting that: "Injunctions don’t work. You take out an injunction against somebody or some organisation and immediately news of that injunction and the people involved and the story behind the injunction is in a legal-free world on Twitter and the Internet. It’s pointless."[189]

Clarkson is a fan of the progressive rock band Genesis and attended the band's reunion concert at Twickenham Stadium in 2007. He also provided sleeve notes for the reissue of the album Selling England by the Pound as part of the Genesis 1970–1975 box set.[190]

Clarkson was involved in a protracted legal dispute about access to a "permissive path" across the grounds of his second home, a converted lighthouse, on the Isle of Man between 2005 and 2010, after reports that dogs had attacked and killed sheep on the property.[191][192] Clarkson and his wife had claimed that four sheep were deliberately killed after being chased into the sea by a dog let off its lead.[193] He lost the dispute after the Isle of Man government held a public inquiry, and he was told to re-open the footpath.[194] The decision was affirmed by the Isle of Man High Court.[195]

On 4 August 2017, he was admitted to hospital after falling ill with pneumonia while on a family holiday in Majorca, Spain, and was being treated in a hospital there.[196] He subsequently said he could "breathe out harder and for longer than a non-smoking 40-year-old" and had 96 per cent capacity for a person his age. "In short, getting on for three-quarters of a million fags have not harmed me in any way. I have quite literally defied medical science".[197]

In January 2021, Clarkson revealed he had tested positive for COVID-19 during December 2020 after displaying symptoms.[198][199]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1988–2000 | Top Gear | Presenter | |

| 1995–1996 | Jeremy Clarkson's Motorworld | 13 episodes | |

| 1995 | Jeremy Clarkson's Motorsport Mayhem | VHS/DVD Exclusive | |

| 1996 | More Motorsport Mayhem | VHS Exclusive | |

| Jeremy Clarkson: Unleashed on Cars | |||

| 1997 | Apocalypse Clarkson | ||

| 1998 | Jeremy Clarkson's Extreme Machines | 1 series (6 episodes) | |

| Robot Wars | 1 series (6 episodes) | ||

| The Most Outrageous Jeremy Clarkson Video in the World...Ever! | VHS Exclusive | ||

| 1998–2000 | Clarkson | 3 series (27 episodes) | |

| 1999 | Jeremy Clarkson: Head to Head | VHS/DVD Exclusive | |

| 2000 | Clarkson's Car Years | 1 series (6 episodes) | |

| Jeremy Clarkson: At Full Throttle | VHS/DVD Exclusive | ||

| 2001 | Speed | 1 series (6 episodes) | |

| Clarkson's Top 100 Cars | VHS/DVD Exclusive | ||

| 2002 | Jeremy Clarkson: Meets the Neighbours | 5 episodes | |

| 100 Greatest Britons | One-off | ||

| Clarkson: No Limits | VHS/DVD Exclusive | ||

| 2002–2015, 2021 | Top Gear | 22 series (175 episodes + 11 specials)

Reappeared in a one off special to look back at the Life of Sabine Schmitz in 2021 | |

| 2002–2015 | Have I Got News for You | 13 episodes | |

| 2003 | Grumpy Old Men | Participant | |

| The Victoria Cross: For Valour | Presenter | One–off | |

| Clarkson: Shoot Out | VHS/DVD Exclusive | ||

| 2004 | Inventions That Changed the World | 1 series (5 episodes) | |

| Clarkson: Hot Metal | VHS/DVD Exclusive | ||

| Who Do You Think You Are? | Participant | Series 1, Episode 4 (2 November 2004) | |

| 2004–2016 | QI | ||

| 2005 | Clarkson: Heaven and Hell | Presenter | DVD Exclusive |

| 2006 | Never Mind the Buzzcocks | Guest host – 1 episode | |

| Cars | Harv (Voice; UK version only) | Movie | |

| Clarkson: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly | Presenter | DVD Exclusive | |

| 2007 | Jeremy Clarkson: The Greatest Raid of All Time | One–off | |

| Clarkson: Supercar Showdown | DVD Exclusive | ||

| 2008 | Clarkson: Thriller | ||

| 2009 | Clarkson: Duel | ||

| 2010 | Clarkson: The Italian Job | ||

| 2011 | Forza Motorsport 4 | Video Game | |

| Clarkson: Powered Up | DVD Exclusive | ||

| 2013 | Phineas and Ferb | Adrian (Voice) | |

| Forza Motorsport 5 | Presenter | Video game | |

| 2014 | PQ17: An Arctic Convoy Disaster | ||

| 2015 | TFI Friday | Participant[200] | |

| 2016–present | The Grand Tour | Presenter | 4 series |

| 2018–present | Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? | 6 series (53 episodes) | |

| 2020–present | It's Clarkson On TV | 3 episodes | |

| 2021 | Clarkson's Farm | 1 series (8 episodes) |

Bibliography

| Book | Publisher | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Jeremy Clarkson's Motorworld | BBC Books Penguin Books |

1996 Reprinted 2004 |

| Clarkson on Cars | Virgin Books Penguin Books | |

| Clarkson's Hot 100 | Virgin Books Carlton Books |

1997 Reprinted 1998 |

| Planet Dagenham | Andre Deutsch Carlton Books |

1998 Reprinted 2006 |

| Born to be Riled | BBC Books Penguin Books |

1999 Reprinted 2007 |

| Jeremy Clarkson on Ferrari | Lancaster Books Salamander Books |

2000 Reprinted 2001 |

| The World According to Clarkson | Icon Books Penguin Books |

2004 Reprinted 2005 |

| I Know You Got Soul | Michael Joseph Penguin Books |

2005 Reprinted 2006 |

| And Another Thing...: The World According To Clarkson Volume 2 | 2006 Reprinted 2007 | |

| Don't Stop Me Now!! | 2007 Reprinted 2008 | |

| For Crying Out Loud!: The World According To Clarkson Volume 3 | 2008 Reprinted 2009 | |

| Driven To Distraction | 2009 Reprinted 2010 | |

| How Hard Can It Be?: The World According To Clarkson Volume 4 | 2010 Reprinted 2011 | |

| Round The Bend | 2011 Reprinted 2012 | |

| The Top Gear Years | Penguin Books | 2012 Reprinted 2013 |

| Is It Really Too Much To Ask?: The World According To Clarkson Volume 5 | 2013 Reprinted 2014 | |

| What Could Possibly Go Wrong... | 2014 Reprinted 2015 | |

| As I was saying...: The World According To Clarkson Volume 6 | 24 September 2015 | |

| If You'd Just Let Me Finish | October 2018 |

- Two books containing the best columns from previous publications, entitled "The Collected Thoughts of Clarkson" and "Never Played Golf", were issued by Top Gear magazine, in 2003 and 2004 respectively.

Britcar 24 Hour results

| Year | Team | Co-Drivers | Car | Car No. | Class | Laps | Pos. | Class Pos. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | BMW 330d | 78 | 4 | 396 | 39th | 3rd |

References

- ^ a b c Parkinson, Justin (25 March 2015). "The Jeremy Clarkson story". BBC News. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Peel P50 feature". Top Gear. Series 10. Episode 3. 28 October 2007.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson dropped by BBC after damning report into assault on producer". The Guardian. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Summary text of BBC's report into Jeremy Clarkson 'fracas'". The Guardian. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Eddie Clarkson & Shirley Clarkson Married, Children, Joint Family Tree & History – FameChain".

- ^ a b "Desert Island Discs – Jeremy Clarkson". BBC Radio4. 16 November 2003. Archived from the original on 3 September 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ Clarkson, Shirley (23 June 2008). Bearly Believable: My Part in the Paddington Bear Story. Harriman House Publishing. ISBN 978-1-905641-72-7.

- ^ a b Eckford, Alex (16 July 2010). "Jeremy Clarkson's mum lifts lid on famous son". Autotrader. Auto Trader Group. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "Inside Hamleys at Christmas". Inside Hamleys at Christmas. December 2018. Channel 5 (UK).

- ^ "Clarkson was suicidal at school after being bullied". 5 June 2016. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Patrick, Patrick (November 2003). "Jeremy Clarkson's Fact File". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

He claims to have been expelled from his public school for drinking, smoking and generally making a nuisance of himself.

- ^ https://twitter.com/JeremyClarkson/status/1293826911752392705 [bare URL]

- ^ Batra, Ruhi. "Newey giving shape to Red Bull dreams". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "The Radio Academy". William ('Uncle David') Davis. The Radio Academy (a registered charity dedicated to the encouragement, recognition and promotion of excellence in UK broadcasting and audio production). Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

Among the schoolboy actors who passed through the Jennings plays before their voices broke, incidentally, was Jeremy Clarkson

- ^ Jeremy Clarkson (2013). Jeremy Clarkson on LBC 97.3 (Online video). Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Jeremy Clarkson Archived 28 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

- ^ "Sacked Clarkson tells how his road to motoring fame started in Shropshire". Shropshire Star. 27 March 2015. p. 4.Report by David Banner.

- ^ Jeremy Clarkson at AskMen.com Archived 6 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson Amstrad Game Reviews". Imgur. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson". IMDb. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Ross, Tom (26 March 2015). "Was Jeremy Clarkson trouble from the start? He sure was". The Guardian.

- ^ Parkinson, Justin (25 March 2015). "The Jeremy Clarkson story". BBC News.

- ^ a b c "Jeremy Clarkson, Top Gear host, suspended by BBC after 'fracas'". BBC News. 10 March 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Clarkson, Jeremy (27 April 2007). "Your Clarkson needs you". Top Gear Magazine. BBC Worldwide. Archived from the original on 28 May 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

...we finished with 8.6 million people watching the end of the final show. To put that in perspective, it's pretty much twice what a very successful programme could dream of getting on BBC2 or Channel 4. It puts us on level terms with Eastenders.

- ^

Savage, Mark (21 September 2006). "Top Gear's chequered past". BBC News. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

It is currently shown in more than 100 countries around the world, and Top Gear magazine is the UK's biggest-selling car magazine.

- ^ "Top Gear: Jeremy Clarkson netted more than £14m from show last year". Guardian. 16 July 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Conlan, Tara; Sabbagh, Dan (27 September 2012). "Top Gear deal nets Jeremy Clarkson multi-million pound payout". Guardian. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Robot Wars". SphereTV. Archived from the original on 5 December 2006. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- ^ "Worst-Dressed Winners". Vogue. Condé Nast Publications. 27 August 2002. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

FAMED fashion commentators Susannah Constantine and Trinny Woodall have come up with a definitive worst-dressed list to coincide with the launch of a new series of their What Not to Wear programme....While each candidate was invited onto the show for a full wardrobe makeover, only Birds of a Feather actress Lesley Joseph (who "looks like a pantomime dame"), and Jeremy Clarkson ("who looks like he should be selling vegetables in the market"), have accepted. Their reward for having their fashion sense publicly torn apart is that they will avoid winning the all-time Worst-Dressed title.

- ^ "BBC ONE honours the best TV moments from 2002" (Press release). BBC Press Office. 1 February 2003. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

Trinny and Susannah suggest alternatives to Jeremy Clarkson's wardrobe with very little success. Every suggested outfit is "shot down in flames" by Jeremy causing an exasperated Trinny to ask him why he agreed to appear on the programme.

- ^ "Mammary mia!". The Sunday Herald. 8 September 2002. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

"I'd rather eat my own hair than shop with these two again," said Jeremy Clarkson, who was lured onto their show after they picked him out as one of the "world's worst-dressed men".

- ^ a b "Who Do You Think You Are? – Jeremy Clarkson" (Press release). BBC. 24 September 2004. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

- ^ a b "Who Do You Think You Are? with Jeremy Clarkson". Who Do You Think You Are?. UK. 2 November 2004. BBC. BBC Two.

- ^ "Episode 1". Have I Got News for You. Series 50. Episode 1. 2 October 2015. BBC One.

- ^ "Bafta TV Awards 2006: The winners". BBC Online. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Pay us the same as Clarkson – or we quit! The Independent (London), 5 July 2008

- ^ "BBC – Top Gear – The Show – Production Notes – Polar Special". Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "Top Gear smash pictures released". BBC Online. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ Sweney, Mark (16 July 2013). "Top Gear: Jeremy Clarkson netted more than £14m from show last year". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ Plunkett, John. "Top Gear's Clarkson, Hammond and May sign Amazon deal". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Plunkett, John. "Top Gear's Jeremy Clarkson, Richard Hammond and James May making show for Amazon". BBC News. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Ruby, Jennifer (11 May 2016). "Jeremy Clarkson's new Amazon show is called The Grand Tour". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson replaces Chris Tarrant on Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?". BBC News. 9 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e BBC News Clarkson: 'I'd be a rubbish PM', 27 May 2008

- ^ Wright, Oliver; Williams, Rob (11 April 2013). "Jeremy Clarkson, Shirley Bassey and Tony Blair, but no Mikhail Gorbachev: Margaret Thatcher's funeral guest list announced". The Independent. London. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Farnum, Michael (7 January 2008). "Payback for credit fraud nay-sayer". Computerworld. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ "Brexit: Which Celebrities Are in and Which Are Out?". Newsweek. 21 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Jeremy Clarkson: Trump is Bad, But Brexit is a Thousand Times Worse". MSN. 8 January 2019.

- ^ Oppenheim, Maya (13 March 2016). "Jeremy Clarkson announces he wants Britain to stay in the EU to create a 'United States of Europe'". The Independent on Sunday. London. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ BBC News Clarkson quizzed over gang ordeal, 6 December 2007

- ^

Clarkson, Jeremy (1 May 2005). "Peugeot 1007 – Brilliant, the doors are useless, 1 May 2005". The Times. London. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

So what, exactly, is God's most stupid creation? The pink flamingo, the avocado pear, Stephen Joseph from the pressure group Transport 2000?

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson 'Considering Bid To Be MP'". BSkyB. 14 September 2013.

- ^ Clarkson, Jeremy (15 March 2009). "I'm starting divorce proceedings in this special relationship". The Times. London.

- ^ Clarkson, Jeremy (2 July 2006). "The united states of total paranoia". The Times. London.

- ^ "Announce London as the capital of America, Ex-Top Gear star Jeremy Clarkson advises Palestine". The Siasat Daily. 9 December 2017.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson Says He Could Vote Labour Under Keir Starmer". HuffingtonPost. 6 July 2020.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson: I might vote Labour under Keir Starmer". The Times. 6 July 2020.

- ^ Saul, Heather (12 March 2015). "Jeremy Clarkson 'punched' Top Gear producer because he wanted a steak". The Independent.

- ^ This has been my perfect week Clarkson Times column 13 January 2008

- ^ a b c "Okay, you’ve got me bang to rights – I'm a secret green" The Times, 17 May 2009

- ^ ruralvoice.co.uk, March 2012

- ^ a b "The People vs Jeremy Clarkson". The Independent. London. 13 November 2005.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson finally recognises climate crisis during Asia trip". The Guardian. 24 November 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "The Grand Tour: Jeremy Clarkson show confronts climate change". BBC News. 2 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson slams climate change protesters as 'happy clappy eco vicars'". Metro. 17 April 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Jeremy Clarkson host blasts Greta as 'spoilt brat'". NewsComAu. 30 September 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ Editorial, Reuters. "UK broadcaster Jeremy Clarkson calls Greta Thunberg 'mad and dangerous' | Reuters Video". reut.rs]. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Curtis, Polly (12 September 2005). "Clarkson hit by pie at degree ceremony". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

The controversial BBC motoring presenter Jeremy Clarkson today received an honorary degree from Oxford Brookes University – and a banana meringue pie in the face from an environmental protester. Mr Clarkson was met by a peaceful demonstration of around 20 activists who objected to his being awarded the degree. During a photocall following the ceremony one campaigner threw the pie, which protesters later claimed was organic, in his face.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson targeted in manure dump protest by climate campaigners". The Guardian. 17 September 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ [Top Gear Series 15, Episode 2]

- ^ "Lessons from London's congestion charge" (Fee required). The Economist. 22 February 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- ^ Auto Trader Clarkson versus the world, 13 April 2007

- ^ a b "Clarkson in the doghouse". BBC News. 26 October 1998. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

- ^ Hargreaves, Ian (5 February 2001). "A nation mocked too much". The New Statesman. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ^ a b "Biker banned days after TV gaffe". BBC News Wales. BBC. 31 October 2002. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ^ McCarthy, James (6 January 2008). "Wales snubs bid to make Clarkson PM". Wales on Sunday. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson, Doctor of Engineering (HonDEng)". Oxford Brookes University. Archived from the original on 29 December 2009.

- ^ Degree honour Clarkson hit by pie, BBC News, 12 September 2005.

- ^ "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] PMClarkson – epetition response". Number10.gov.uk. 19 August 2008. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "BBC Top Gear Host Jeremy Clarkson – 2011 Power List". Motor Trend. 13 December 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ Hamilton, Fiona; Coates, Sam; Savage, Michael (8 November 2005). "Clarkson and Gill in Baghdad your views". The Times. London. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ [1] The Victoria Cross: For Valour at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ "Help for Heroes official site". Helpforheroes.org.uk. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ Hamilton, Fiona; Coates, Sam; Savage, Michael (2 December 2007). "Clarkson's hero". The Times. UK. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ "Graduation Ceremonies 2003—Honorary Degree for Jeremy Clarkson". Brunel University. July 2003. Archived from the original on 2 August 2003. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Flintoff, John-Paul (2010). Through the Eye of a Needle. Permanent Publications. p. 80. ISBN 9781856230452.

- ^ [2] English Electric Lightning – Pictures – Survivors. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ^ Time Online Bugatti Veyron – Utterly, stunningly, jaw droppingly brilliant, 27 November 2005

- ^ Top Gear. Series 7. Episode 5. 11 December 2005. BBC Two.

- ^ "The Clarkson Review: Range Rover 350D Vogue SE". The Sunday Times. 10 January 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Clarkson, Jeremy (13 January 2008). "Mazda MX-5: It's far too cool for you, Mr Footballer". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- ^ Clarkson, Jeremy (15 March 2009). "Range Rover TDV8 Vogue SE". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson reveals what happens to Grand Tour Cars". Metro. 26 July 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ a b c "Jeremy Clarkson's Cars". Motoring Research. 21 September 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson loves Range Rovers so much he'll ignore the new one's biggest problem". Sunday Times Driving. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "Jeremy's new car breaks down". DriveTribe. 19 January 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ a b Clarkson, Jeremy (2011). Round the Bend. Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-7181-5842-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Clarkson, Jeremy (2011). Round the Bend. Penguin Books Ltd. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-7181-5842-2.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson on Sports Cars". topgear.com. 5 March 1997. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Top Gear Star Clarkson's Ford for sale". Autotrader. 31 August 2007. Archived from the original on 10 December 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Clarkson, Jeremy (15 August 2016). "Jeremy Clarkson's Star Cars". Sunday Times. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Clarkson's Car Years: The All New Family Car 2000. BBC. 2000.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson's SL55". youtube. 27 September 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ a b Clarkson, Jeremy (18 January 2009). "Volvo XC90". The Times. London.

- ^ The world according to Clarkson, Sunday Times, 30 April 2006

- ^ a b Top Gear, Season 8, Episode 1 7 May 2006

- ^ Top Gear : the official annual 2009. London: BBC Children's. 2008. p. 6. ISBN 9781405904551. OCLC 262682080.

- ^ Clarkson, Jeremy (13 May 2012). "The Clarkson review: Mercedes-Benz SLK 55 AMG (2012)". Driving.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ "Jeremy's CL Inspected". topgear.com. 15 August 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson Drives a Volkswagen Golf GTI, Captain Power Doesn't Care About its Emissions". autoevolution. 27 September 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ "Madagascar Special was The Grand Tour's Toughest Trip yet, says Jeremy Clarkson". Sunday Times Driving. 6 December 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Jeremy Clarkson – "The Italian Job" DVD

- ^ Clarkson drives a Skoda Yeti, Top Gear, BBC Worldwide Ltd., Series 16, Episode 1|date=July 2011 Archived 8 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alfa Romeo Brera marketing video released at Autoblog. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ^ Jeremy Clarkson. Top Gear 2 January 2005 (TV). London: BBC.

- ^ "Vauxhall Monaro VXR: It's back-breakingly marvellous", The Sunday Times Online, 10 July 2005.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson's Top Gear Love Letter to the Lexus LFA". Lexus Enthusiast. 3 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ Clarkson, Jeremy (24 April 2005). "Goodbye, Rover. Sorry, I won't be shedding a tear". The Times. London. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ White, Roland (6 November 2005). "Lib Dem MP identifies Clarkson as a global threat". The Sunday Times. p. 17.

- ^ a b Clarkson, Jeremy (5 June 2005). "Vauxhall Astra SRi: Vauxhall, I forgive you (almost) everything". The Times. London. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- ^ Jeremy Clarkson. Top Gear 16 July 2006 (TV). London: BBC.

- ^

O'Grady, Sean (13 September 2005). "Vroom with a view: The crown prince of petrolheads; Jeremy Clarkson is the self-appointed scourge of the green movement". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 March 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

And never, ever could he be likened to a Vauxhall Vectra. That was the vehicle that underwhelmed Jeremy so much that on its launch, he made a satirical little film about it for Top Gear. He just walked around the family hatchback, rubbing his chin and shaking his head a bit, saying absolutely nothing. It was a characteristically clever trick, but it didn't do the folks who made that car any favours. The Vectra wasn't the smash hit that Vauxhall hoped it would be.

- ^ Woodman, Peter (19 October 1995). "Top Gear gives new Vauxhall a second chance". The Press Association.

- ^ BBC News – BBC stumps up for tree stunt, 21 February 2004

- ^ "ECU ruling: Top Gear, BBC Two". BBC Complaints. 15 December 2006. Archived from the original on 10 January 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2006.

In this instance there was no editorial purpose which would have served to justify the potential offence, and the complaints were therefore upheld.

- ^ BBC News Top Gear rapped for alcohol use, 2 July 2008

- ^ Hall, Alan (15 December 2005). "Germans up in arms over Clarkson's mocking Nazi salute". The Scotsman. Edinburgh, UK: Johnston Press. Archived from the original on 3 June 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

Clarkson raised his arm Nazi-style as he spoke about the German company BMW's Mini. Then, mocking the 1939 invasion that triggered the Second World War, he said it would have a satellite navigation system "that only goes to Poland". Finally, in a reference to Adolf Hitler's boast that his Third Reich would last ten centuries, Clarkson said the fan belt would last for 1,000 years. The German government is said to be highly displeased: diplomats pointed out that, had Clarkson made the Nazi salute on German television, he could be facing six months behind bars as, joking or not, such behaviour is illegal under the country's post-war constitution. The German motoring press, initially sharply critical of Clarkson's constant anti-German diatribes, nowadays portrays him as a sore loser, i.e. someone who simply hasn't understood yet that English carmaking is as much a thing of the past as tophats and the colonial empire.

- ^ a b c Jeremy Clarkson sparks fresh BBC row The Times, 4 November 2008

- ^ a b Staff writer (6 November 2008). "MP calls for Clarkson to lose job", BBC News Online. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ Clarkson, Jeremy (9 November 2008). "Into the breach, normal people, and sod the polar bears", The Sunday Times, Times Newspapers. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ a b Leigh Holmwood and Chris Tryhorn "Clarkson crashes into trouble with C-word attack on PM", The Guardian, 24 July 2009.

- ^ "Clarkson in new Brown insult row ", BBC News, 25 July 2009

- ^ Wightman, Catriona (6 July 2010). "TV – News – Clarkson slammed for 'Top Gear' gay remark". Digital Spy. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "Top Gear 'speciale needs' joke offensive, says Ofcom". BBC News. 25 October 2010.

- ^ Sweney, Mark (12 January 2012). "Top Gear special prompts complaint from Indian high commission". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ^ Dowell, Ben (10 February 2012). "Jeremy Clarkson's 'facial growth' comment prompts complaints". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Josh Halliday and Nicholas Watt "BBC under pressure to sack Jeremy Clarkson over N-word claims", The Guardian, 1 May 2014

- ^ Josh Halliday, Nicholas Watt and Kevin Rawlinson Jeremy Clarkson 'begs forgiveness' over N-word footage The Guardian, 1 May 2014

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson given final warning by the BBC", The Guardian (London), 3 May 2014

- ^ "Top Gear Producer Very Sorry About Jeremy Clarkson's Offensive Remark in Burma Special". The Huffington Post. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Protests cut short Top Gear shoot". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 3 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ "'Top Gear' Patagonia Special Finds Clarkson Poking Fun at Ofcom Racism Row For His Use of Word 'Slope'". The Huffington Post UK. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Barber, Lynn (20 November 2005). "I should have been fired years ago, to be honest". The Observer. London. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "Malaysia lambasts Top Gear host". BBC News. BBC. 4 April 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

In one article, he said its name was like a disease and suggested it was built in jungles by people who wear leaves for shoes.

- ^ McCusker, Eamonn (9 November 2005). "Clarkson: Heaven and Hell". DVD TImes. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ^ Summers, Deborah (6 February 2009). "Scottish politicians urge BBC to take Jeremy Clarkson off air over Gordon Brown jibes". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ Pykett, Emily (7 February 2009). "news.scotsman.com". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "theherald.co.uk". The Herald. 7 February 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Clarkson apologises for PM remark". BBC News. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ Gaskell, Simon (3 September 2011). "Jeremy Clarkson under fire over call for Welsh language to be abolished". WalesOnline. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson apologises over strike comment". BBC News. 1 December 2011.

- ^ "Complaints over Clarkson One Show comments reach 21,000". BBC News. 2 December 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson: Train Suicides Are 'Selfish'". Sky News HD. 3 December 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ MSN.com News Archived 29 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine Jeremy Clarkson in new road safety row, 27 October 2005

- ^ Clarkson, Jeremy (27 November 2007). "Bugatti Veyron – Utterly, stunningly, jaw droppingly brilliant". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- ^ "Clarkson speeding case dismissed". BBC News. 6 September 2007.

- ^ BBC News Clarkson's speed claim criticised, 28 May 2008

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (8 July 2013). "Jeremy Clarkson suspended from Top Gear: as it happened". Telegraph. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ Saul, Heather (13 March 2015). "Jeremy Clarkson: David Cameron backs 'friend' and 'huge talent' after witnesses claim Top Gear 'fracas' was over steak". The Independent. London. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ MacQuarrie, Ken. "Investigation findings" (PDF). bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson 'punch': Top Gear episodes to be dropped". BBC News. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ a b Conlan, Tara (24 February 2016). "Jeremy Clarkson apologises to former Top Gear producer Oisin Tymon". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson dropped from Top Gear, BBC confirms". BBC News. BBC. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (11 March 2015). "Jeremy Clarkson suspended: James May confirms Top Gear host was in 'a dust-up' with producer over dinner". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

It has also emerged that the three presenters could walk away from Top Gear before the BBC's investigation into Clarkson's behaviour is concluded, as their contracts expire at the end of this month and they have not yet signed new three-year deals that were expected to be completed within days.

- ^ Plunkett, John; Sweney, Mark; Conlan, Tara (11 March 2015). "BBC faces multimillion-pound bill from Jeremy Clarkson's suspension". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

Clarkson could walk away from the show when his contract runs out at the end of this month whatever the verdict of the BBC's inquiry into the affair.

- ^ "Top Gear: 350,000 sign petition supporting Jeremy Clarkson". BBC News. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Fans petition BBC to reinstate 'Top Gear' host Jeremy Clarkson". The New York Times. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Petition backing Jeremy Clarkson hits one million signatures". The Daily Telegraph. London. 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Dearden, Lizzie (11 March 2015). "Jeremy Clarkson petition 'BBC Bring Back Clarkson' is now officially the fastest-growing Change.org campaign in history". The Independent. London. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson in sweary rant against BBC bosses", The Guardian, 20 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson: BBC comments 'meant in jest'". BBC News. 22 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "BBC – BBC Director-General's statement regarding Jeremy Clarkson – Media centre". Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson could face police investigation after BBC dismissal". The Guardian. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Top Gear producer 'won't press charges' against Jeremy Clarkson". BBC News. 27 March 2015.

- ^ Selby, Jenn (27 March 2015). "Jeremy Clarkson calls on trolls to leave producer Oisin Tymon alone: 'None of this is his fault'". The Independent. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson: BBC chief Tony Hall receives death threats after decision to drop Top Gear presenter". ABC News. 29 March 2015.

- ^ Butterfly, Amelia (26 March 2015). "Jeremy Clarkson has been offered a new job but it's in Russia". BBC Newsbeat. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Jeremy Clarkson recalls cancer scare before Top Gear 'fracas'". BBC News. 19 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Melvin, Don (13 November 2015). "Former 'Top Gear' host Jeremy Clarkson sued for racial discrimination". CNN.

- ^ Saul, Heather (13 November 2015). "BBC Top Gear producer 'suing Jeremy Clarkson and BBC' for racial discrimination". The Independent.

- ^ a b Singh, Anita; Gardner, Bill; Prynne, Miranda (5 May 2014). "Jeremy Clarkson divorce: 'Mrs Clarkson deserves every penny'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Dewar, Caroline (5 March 2012). "Who's who in the Chipping Norton set". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 6 May 2012.