Rikishi

A rikishi (Japanese: 力士), sumōtori (相撲取り) or, more colloquially, osumōsan (お相撲さん), is a professional sumo wrestler. Rikishi are expected to live according to centuries-old rules and most come from Japan, the only country where sumo is practiced professionally. Participation in official tournaments (honbasho) is the only means of marking achievement in sumo and the rank of an individual rikishi is based solely on official wins.

Terminology

In popular use, the term rikishi can mean any sumo wrestler and be an alternative term to sumotori (sumo practitioner) or the more colloquial sumosan. The two kanji characters that make up the word rikishi are "strength/power" and "gentleman/samurai"; consequently, and more idiomatically, the term can be defined as "a gentleman of strength".

Within the world of professional sumo, rikishi is used as a catch-all term for wrestlers who are in the lower, un-salaried divisions of jonokuchi, jonidan, sandanme and makushita. The more prestigious term sekitori refers to wrestlers who have risen to the two highest divisions of jūryō and makuuchi and who have significantly more status, privilege and salary than their lower-division counterparts.

Lifestyle of rikishi

The life of a professional sumo wrestler is strictly regimented and has detailed prescriptions and rules for rikishi that have been observed for centuries, so much so that rikishi can be seen more as a way of life than a career.

They are expected to grow their hair long to form a topknot or chonmage, similar to the samurai hairstyles of the Edo Period. Furthermore, they are expected to wear the chonmage and traditional Japanese dress at all times when in public. Sumo life centers around the training stables, to which all active wrestlers must belong. Most wrestlers, and all junior ones, live in their stable in a dormitory style: training, cleaning, eating, sleeping and socializing together.

Foreign-born rikishi

Professional sumo is practiced exclusively in Japan, but wrestlers of other nationalities participate. As of August 2009[update] there were 55 wrestlers officially listed as foreigners.[1] In July 2007, there were 19 foreigners in the top two divisions, which was an all-time record, and for the first time a majority of wrestlers in the top san'yaku ranks were from overseas.[2] More recently, the ratio of foreigners has stabilized and as of November 2011[update] there were 18 foreigners in the two top divisions.

A Japanese-American, Toyonishiki, and the Korean-born Rikidōzan achieved sekitori status prior to World War II, but neither were officially listed as foreigners. The first non-Asian to achieve fame and fortune in sumo was Hawaii-born Takamiyama. He reached the top division in 1968 and in 1972 became the first foreigner to win the top division championship. He was followed by a fellow Hawaii-born 287 kilograms (633 lb) mega-weight Konishiki, of ethnic Samoan descent, the first foreigner to reach the rank of ōzeki in 1987; and the Native Hawaiian Akebono, who became the first foreign-born yokozuna in 1993. Musashimaru, born in Samoa and raised in Hawaii, became the second foreigner to reach sumo's top rank in 1999. Four straight yokozuna, retired Asashōryū, Harumafuji Kōhei and Kakuryū Rikisaburō, and still-active Hakuhō are all Mongolian. In 2012, the Mongolian Kyokutenhō became the oldest wrestler in modern history to win a top division championship.[3] Wrestlers from Eastern European countries such as Georgia and Russia have also found success in the upper levels of sumo. In 2005, Kotoōshū from Bulgaria became the first wrestler of European birth to attain the ōzeki ranking and the first to win a top division championship.[4] In another milestone, Brazilian Ryūkō Gō became the first foreign born wrestler to be given makushita tsukedashi status.

Until relatively recently, the Japan Sumo Association had no restrictions at all on the number of foreigners allowed in professional sumo. In May 1992, shortly after the Ōshima stable had recruited six Mongolians at the same time, the Sumo Association's new director Dewanoumi, the former yokozuna Sadanoyama, announced that he was considering limiting the number of overseas recruits per stable and in sumo overall. There was no official ruling, but no stable recruited any foreigners for the next six years.[5] This unofficial ban was then relaxed, but only two new foreigners per stable were allowed, until the total number reached 40.[5] Then in 2002, a one foreigner per stable policy was officially adopted, though the ban was not retroactive, so foreigners recruited before the changes were unaffected. The move has been met with criticism.[5] John Gunning claims it was introduced not for any racial reasons, but to ensure that foreign rikishi assimilate into sumo culture. He explained, there would be ten Hawaiian wrestlers in the same stable living in their own "little clique," not learning Japanese, so the rule "protects the culture of stables."[6]

Originally, it was possible for a place in a stable to open up if a foreign born wrestler acquired Japanese citizenship. This occurred when Hisanoumi changed his nationality from Tongan at the end of 2006, allowing another Tongan to enter his stable,[7] and Kyokutenhō's change of citizenship allowed Ōshima stable to recruit Mongolian Kyokushūhō in May 2007. However, on February 23, 2010 the Sumo Association announced that it had changed its definition of "foreign" to "foreign-born" ('gaikoku shusshin'), meaning that even naturalized Japanese citizens will be considered foreigners if they were born outside of Japan. The restriction on one foreign wrestler per stable was also reconfirmed. As Japanese law does not recognize subcategories of Japanese citizen, this unique treatment of naturalized citizens may well be illegal under Japanese law, although the restriction has never been challenged in court.[8]

Rikishi in contrast to other martial arts practitioners

While sumo is considered a martial art, it diverges from the typical Eastern style both at the surface and at its heart. Whereas most martial arts award promotions to practitioners through time and practice, a rikishi's sumo rank can be gained and lost every two months in the official tournaments. Conversely, in more common Japanese martial arts (such as karate), ranks are gained after passing a single test, and practitioners of karate are not normally demoted, even after repeated poor performances at tournaments. This divergence from other martial arts creates a high-pressure, high-intensity environment for rikishi. All the benefits that sekitori wrestlers receive can be taken from them if they fail to maintain a high level of achievement in each official tournament (or honbasho).

Furthermore, sumo does not provide any means of achievement besides the official tournaments. A rikishi's rank is determined solely by his number of wins during an official tournament. On the other hand, in many other Eastern martial arts, competitors can display their skill by performing standard routines, called kata or forms, to receive recognition. Thus, sumo wrestlers are very specialized fighters who train to win their bouts using good technique, as this is their only means of gaining better privileges in their stables and higher salaries.

Former rikishi in mixed martial arts

The numerous differences between sumo and its martial arts counterparts have not deterred many former sumo wrestlers from competing in mixed martial arts. Most have had limited achievement; perhaps the most successful sumo wrestler to have competed in MMA is Tadao Yasuda who holds a record of two wins and four losses. Sumo wrestlers are seen as generally ineffective in MMA because the sports are vastly different from one another in achieving victory; striking techniques and submissions are required for MMA and neither are taught in sumo wrestling. A few key sumo techniques which require grabbing the belt or pants of the opponent also become ineffective, as this is illegal in MMA.

Other sumo wrestlers to have fought in mixed martial arts include Baruto Kaito, Alan Karaev, Ōsunaarashi Kintarō, Kōji Kitao, Henry Armstrong Miller, Akebono Tarō, Teila Tuli and Wakashoyo. Former UFC Light Heavyweight Champion Lyoto Machida also has a sumo background but his main style is Shotokan Karate.

Gallery

- Gallery

-

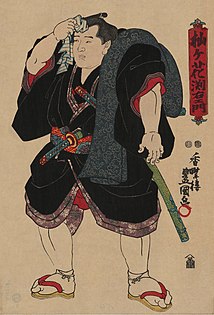

97 Rikishi of the Edo Period by Utagawa Kuniteru

-

Sumo wrestler Somagahana Fuchiemon, c. 1850

See also

References

- ^ "Foreigners in Sumo". dichne.com. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (July 3, 2007). "Last of the Sumo – Japanese youth turn their backs on gruelling sport of emperors". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- ^ "Kyokutenho beats Tochiozan for title". Japan Times. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "Bulgarian ozeki Kotooshu first European to win Emperor's Cup". Japan Times. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ a b c Hiroyuki Tai (November 25, 2005). "Foreign sumo aspirants' numbers kept in check by stable quota policy". Japan Times. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ^ K, Josh (March 10, 2018). ""It's not a sport. It's a lifestyle." A Conversation with John Gunning – Part 3". Tachiai.org. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Buckton, Mark (January 23, 2007). "Numbers break records, character creates legends". The Japan Times. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ Arudou, Debito, "Sumo body deserves mawashi wedgie for racist wrestler ruling", Japan Times, March 2, 2010, p. 12.