Narayan Rao

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

Narayanrao | |

|---|---|

| |

| In office 13 December 1772 – 30 August 1773 | |

| Monarch | Rajaram II |

| Preceded by | Madhavrao I |

| Succeeded by | Raghunathrao |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 August 1755 |

| Died | 30 August 1773 (aged 18) Shaniwar Wada |

| Spouse | Gangabai Sathe[1] |

| Relations | Vishwasrao(Elder brother) Madhavrao(Elder brother) |

| Children | Sawai Madhavrao |

| Parents |

|

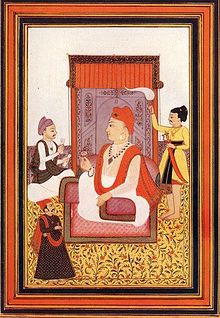

Shrimant Peshwa Narayanrao Bhat (10 August 1755 – 30 August 1773) was the 10th Peshwa of the Maratha Empire from November 1772 until his assassination in August 1773. He married Gangabai Sathe who later gave birth to Sawai Madhavrao Peshwa.

Early life

Narayanrao Bhat was born 10th August 1755. He was the third and youngest son of Peshwa Balaji Baji Rao (also known as Nana Saheb) and his wife Gopikabai. He received a conventional education in reading, writing and arithmetic and possessed a functional understanding of Sanskrit scriptures. He was married to Gangabai Sathe on 18th April 1763 before his eighth birthday. He was very close to Parvatibai, the widow of Sadashivrao, who took him under her care to lessen her sorrows after her husband's death. His eldest brother Vishwasrao, heir to the title of the Peshwa, died in the Battle of Panipat in 1761 along with Sadashivrao. His father died a few months later and his elder brother Madhavrao took over as Peshwa.[2][3]

He accompanied his brother Peshwa Madhavrao in his expeditions to Carnatic on two occasions, once in 1765 and later in 1769. He received a wound in his wrist at the storming of fort Nijagal at the end of April 1770. In last one or two years of his brother's reign, he was placed in the care of the Maratha minister Sakharam Bapu in order to train him in his administrative work. His behaviour and performance of his duties always failed to impress his brother Madhavrao who expressed great fears about his future.[4]

Ascension

Before his death, Peshwa Madhavrao conducted a court session in which the issue of ascension was discussed at length and at the end of which, in the presence of the family deity, he nominated his younger brother Narayanrao as the next Peshwa. He counselled Naraynrao to conduct his administration by the advice of Sakharam Bapu and Nana Padnavis. Raghunathrao, the uncle of both Madhavrao and Narayanrao, didn't have the courage to openly oppose the nomination of Narayanrao in front of the dying Peshwa and so he apparently acquiesced to the arrangement. The Peshwa had also ordered in writing that Raghunathrao was to continue his confinement so as to prevent him from engaging in mischief. Raghunathrao attempted an escape shortly before the Peshwa's death but was immediately caught and put back into confinement.[5]

Peshwa Madhavrao finally died on 18th November 1772. His funeral rites were conducted at Theur and the court returned to Pune on 2nd December. Narayanrao prepared to set off for Satara in order to receive his robes from Chhatrapati Rajaram II. Before he could leave, his uncle Raghunathrao demanded to accompany him to Satara unless he was granted an independent fief of 25 lakhs annually for him and his family. But Raghunathrao was persuaded to give up his demands. And so Narayanrao went to Satara and received his robes from Rajaram II on 13th December. At the same time, Sakharam Bapu took his role as Karbhari ("Chief Administrator") and other officials confirmed their respective posts.[6]

Reign

Alienation of various groups

Gardis

The Peshwas employed Gardi soldiers for police duty around the palace and the city of Pune. The Gardis were less than 5000 strong and were mostly composed of North Indians, Pathans, Ethiopians, Arabs, Rajputs and Purbiyas. Their monthly salary ranged somewhere between Rs. 8 and Rs. 15. According to French military leader and administrator Marquis de Bussy-Castelnau, the Gardis saw their role in purely commercial terms and had no personal attachment to their employer. The new Peshwa Narayanrao inherited an empty treasury from his brother. Madhavrao had lost all the wealth he had accumulated over the years in paying off the empire's debts and had failed to bring funds in the last few years of life due to his illness. On top of that, with Ibrahim Khan Gardi and Marquis de Bussy gone, the Gardis no longer had a overarching leader to keep them disciplined. The unpaid and disorganised Gardis had now become a liability for the Marathas but neither Peshwa nor his advisors paid much attention to the pressing issue.[7]

Prabhus

The Prabhus were an influential community in the Maratha empire. They claimed to be belonging to the Kshatriya ("warrior") caste which gave them the right to perform religious functions throught the use of Vedic chants. A dispute over their caste status had occured in the late 17th century but it was virtually resolved after the founder of the Maratha empire Shivaji and his confidential secretary Balaji Avji Chitnis, a Prabhus by caste, performed the sacred thread ceremony of their sons at the same time by using Vedic chants under the direction of the celebrated Brahmin scholar Gaga Bhatt. This created a precedent that allowed the Prabhus to hold on to their Kshatriya status without interference from orthodox Brahmins. But then Narayanrao decided to take up the cause of the orthodoxy and, likely under the impression from Nana Phadnavis, reduced their caste status from that of Kshatriya ("warrior") to that of Shudra ("servant"). Prominent leaders of the Prabhu community were called together and under severe torture, including starvation, forced to give up their caste status. They were compelled to sign an agreement of nine specific articles, according to which they would give up Kshatriya status and accept Shudra status. This action on the part of Narayanrao lost him the support of an influential community who later supported Raghunathrao.[8]

Sakharam Bapu

Sakharam Bapu's policy which favoured compromise over radicalism was at odds with the rash and irritable behaviour of Narayanrao. The differences between the two quickly came to light during the appointment of the governorship of Vasai. The position had previously been held for a long time by a soldier and diplomat named Visajipant Lele. Sakharam Bapu held him in high regard because he had faithfully served him in several awkward situations that required mutual support. But Visajipant Lele was a corrupt official whose ill deeds were long known to Madhavrao. During the last days of his tenure, Madhavrao dismissed Visajipanth Lele after he misappropriated government property worth 20 lakhs. So when Narayanrao became Peshwa, Visajipanth Lele requested the new Peshwa to reappoint him as the Governor of Vasai. His request was supported by Sakharam Bapu but Narayanrao rejected Bapu's advise and appointed Trimbak Vinayak instead.[9][10]

Narayanrao and Sakharam Bapu also disagreed on the issue of the Patwardhan Sardars. The Patwardhan Sardars had gained enormous power through their loyal service to the late Peshwa which irked Sakharam Bapu and Raghunathrao who took certain steps to lower their prestige, much to the displeasure of Narayanrao. Since the differences between Narayanrao and Sakharam Bapu were growing they decide to consult the opinions of Gopikabai, the widow of Balaji Rao and the eldest member of the family. And so Narayanrao, Sakharam Bapu and Vamanrao Patwardhan, the leading of the Patwardhan family, repaired to Gangapur in the middle of March 1773 to meet ask for her advise. They spent a few days in frank discussion but couldn't arrive at any definite resolution.[11]

Other Maratha officials

The courtiers at Pune had very negative opinions of the new Peshwa whom they described as impatient, irritable, facetious, gullible and immature person who refused to follow the guidance of Sakharam Bapu. Narayanrao had started imitating the manners and behaviour of his elder brother Madhavrao and had openly disrespected Sakharam Bapu and other eldery officials on several occasions.[12] Nana Phadnavis kept himself aloof due to lack of confidence shown towards him. Unlike his senior colleague Sakharam Bapu, he only invovled himself with the administration when absolutely necessary. This explains why Nana Phadnavis did not notice the talks of intrigues and plots taking place in the city.[13] Moroba Phadnavis was another member of the executive government who shared the attitutde of indifference towards the Peshwa. The same was true for the Maratha general Haripant Phadke.[14]

Confinement of Raghunathrao

First attempt to escape

Narayanrao's relationship with his uncle Raghunathrao was cordial at the beginning. When Raghunathrao's daughter Durgabai was about to get married, Narayanrao made the arrangements for the marriage which took place on 7th February 1773.[15] But later when Narayanrao was at Nashik, Raghunathrao tried to take advantage of the Peshwa's absence and plotted his escape. Raghunathrao began to enlist his own troops and wrote to Haidar Ali for support. Naro Appaji, the Maratha officer inchage for law and order in Pune, heightened the security around Raghunathrao by placing guards to watch all the exits of the palace and the city. Raghunathrao pitched his tents outside and declared that he was going on an expedition.[16]

As soon as this news reached Narayanrao he returned back to Pune and found Raghunathrao in his tents. He brought him back to the palace on 11th April 1773 and placed additional guards to prevent his escape. This further strained the relationship between Narayanrao and Raghunathrao.[17] In July 1773, Raghunathrao become so exasperated with the restrictions imposed on him that he threatened to starve himself, his wife and his adopted son to death. Narayanrao failed to sooth things over by compromise. He had no advisors whom he could trust upon at this point.[18]

Second attempt to escape

And so when the two agents arrived at Pune in the summer of 1773 and discovered the tensions between Narayanrao and Raghunathrao, they realised they had much to benefit from the chaos.[19] At the same time Narayanrao continued supporting the claim of Sabaji and sent armed reinforcements under Khanderao Darekar to support him against his brother. This caught the ire of Mudhoji who vaguely told his agents to do whatever they deemed necessary for accomplishing their mission by supporting Raghunathrao's power.[20]

But the agents needed to have a discussion with Raghunathrao before they could formulate a plan. Raghunathrao was in strict confinement at the time and so they approached Sakharam Hari Gupte, a strong partisan of Raghunathrao who had also been incensed by the Peshwa's decision to reduce the caste status of his community. They manage to obtain a secret meeting with Raghunathrao in which they hatch a plan which involved seizing Narayanrao and placing Raghunathrao on the throne. This would require for Raghunathrao to be free and organise an armed foce. In August 1773, during night time, Raghunathrao tried to escape using the help of Lakshman Kashi. But Raghunathrao was caught and taken into custody while Lakshman Kashi managed to escape and fled from Pune.[21]

When news of Raghunathrao's attempted escape reached Narayanrao he made the terms of uncle's confinement harsher. Raghunathrao was no longer allowed to leave his room, all his essentials were delivered to him and his lavish lifestyle was curtailed. As part of his prayer, Raghunathrao would stand in the open and gaze at the sun, but he was now barred from performing it which made him furious. Although the relationship between Madhavrao and Raghunathrao, the former carefully avoided exasperating his uncle beyond a certain limit and skillfully employed his uncle's partisans so as to prevent any action against him. But Narayanrao lacked his elder brother's foresight and so his dissidents were able to find a common goal in supporting his uncle.[22]

Third attempt to escape

Raghunathrao was also able to find the finding the sympathy of Appaji Ram, the ambassador of Haidar Ali at Pune, who managed to persuade his ruler to support Raghunathrao's cause. When Narayan found out about his uncle's plan to escape by enlisting the support Haidar Ali, he confined him in his palace and allowed neither his friends to visit him nor his servants to attend to him. His uncle, whether through exasperation or shrewdness, declared that he would starve himself to death so that his murder would be attributed to his nephew. For the next eighteen days, he consumed nothing except for two ounces of deer milk each day. When he was finally exhaused due to pangs of hunger, his nephew somewhat relented by promising him a district and five castles and a jagir of Rs. 12 lakh per annum, provided some of the great chieftains would become surety for his future conduct.[23]

Foreign policy

Resettlement of old allies

The Marathas led by Mahadji Shinde had recaptured Delhi in 1771. Mahadji Shinde and other Marathas chiefs were later occupied in looking after the affairs of Delhi and collecting revenues from other North Indian districts. Ghazi-uddin Imad-ul-mulk, an ally of the Marathas, was anxious to be reinstalled as the Wazir of the Mughal Empire as he had once been. The Mughal emperor Shah Alam II bitterly hated Ghazi-uddin for he murdering his father and would not give him any help. Meanwhile Ghazi-uddin had been reduced to the status of a vagabond and so he went to Pune in December 1772 to make his case in front of the new Peshwa. In recognition of the services he had rendered onto the Marathas so far, and likely because of a promise made to him by Narayanrao, Nana Padnavis gave Ghazi-uddin a small provision in Bundelkhand. The previous Nawab of Bengal Mir Qasim was another important friend of the Marathas and expected a similar compensation for his services but it was beyond the power of the Peshwa to satisfy him.[24]

British naval attack

In April 1772, as Madhavrao was on his death bed, the President of Bombay Council received orders from the Home authorities to try and acquire from the Maratha certain places such as Salsette, Vasai, Elephanta, Karanja and others islands in the vicinity of Mumbai and to station a British agent in Pune in order to gain that object. British official Thomas Mostyn was chosen for the task as he was already familiar with the Pune court, having led the British mission of 1767. He arrived in Pune on 13th October 1772 and spent the next two years keenly watching the events unfold and advising the Bombay Council to take the necessary steps for the acquisition of those place.[25]

Soon after the death of Madhavrao and ascension to the Maratha throne of his ostensibly weaker brother Narayanrao, the British navy sensing a opportunity started wanton aggression against Maratha posts of Thane, Vasai, Vijaydurg and Ratnagiri on the west coast. But Narayanrao took immediate action by appointing Trimbak Vinayak as the Sar-Subah of Vasai and the Konkan, and dispatched him with necessary funds to counter the British efforts. Trimbak Vinayak and the Maratha naval officer Dhulap of Vijaydurg together successfully repelled the British attack. But Mostyn remained at Pune watching and waiting for another opportunity.[26]

Nagpur succession crisis

The death of the ruler of Nagpur Janoji Bhonsle in May 1772 set off a succession dispute within his family and led to a civil war between his sons Mudhoji and Sabaji. The disputed created ruptures at the Court of Pune as Sakharam Bapu and Raghunathrao supported Mudhoji while Narayanrao, Nana Phadnavis and others supported Sabaji. Sabaji also gained the support of Nizam Ali Khan and fought some battles against him brother whose result turned out to be indecisive. The brothers finally reached an agreement, according to which Mudhoji's son Raghuji was to be made the ruler of Nagpur. The arrangement had to be approved by the Peshwa, and so two agents, Vyankatrao Kashi Gupte and his brother Lakshman, were sent to Pune in order to acquire the robes for Raghuji.

The agents sent to Pune belonged to the Prabhu caste whose members were cross with Narayanrao who, likely under the impression from Nana Phadnavis, had reduced their caste status from that of Kshatriya ("warrior") to that of Shudra ("servant"). Prominent leaders of the Prabhu community were called together and under severe torture, including starvation, forced to give up their caste status. This action on the part of Narayanrao lost him the support of an influential community who later supported Raghunathrao.[27] The two agents then tried to help Raghunathrao escape from his confinement. The actions of the agents exasperated and disgusted the Peshwa who on 16th August 1773 issued orders recognising Sabaji as the rightful ruler of Nagpur and commanded the agents to go back to Nagpur along with the third agent Bhavani Shivam who had just arrived.[28]

Assassination

Preparations

The period between 16th to 30th August witnessed an unprecedented number of secret talks and concealed discussions taking place among the various partisans of Raghunathrao, but as this had been a regular occurrence at the palace, no responsible official paid any serious attention to them. Since Raghunathrao could not leave his confinement, the preparations for the plot were carried out by Tujali Pawar, an influential personal servant of Raghunathrao and his wife Anandibai.[29] Tujali additionally felt he had been wronged by Narayanrao and possibly Madhavrao, and regardless of whether this suppossed offense was real or not, it motivated him to play an integral part in the plot. While the previous plan involved simply capturing Narayanrao, the new plan involved his murder and was partly based on the assumption that Sakharam Bapu would remain neutral with regards to the plot.[30]

The Ganapati festival was held for a period of ten days between 21st and 31st August. The festival was a holiday for the administration and all the officials and staff were occupied with various aspects of the festival such as the worship in the morning and evening, Vedic recitation, music, dance, durbars, feasts and processions.[31] Tulaji met with the Gardi leaders during the Ganesh festival to inform them of the plot being hatched. Since he was an old servant he couldn't be abruptly dismissed even if suspected of a conspiracy and had ready access to his master and his wife in order to plan out various parts of the plot. Sumersinh was the Gardi officer who had been appointed by Narayanrao to be incharge of his uncle and hence had free access to him. He was won over by Tulaji, along with Muhammad Yusuf, Kharagsinh and Bahadur Khan, each of them had about a thousand soldiers working under them. They were promised to be given a cash reward of Rs. 3 lakh if they successfully executed the plot. A written order was produced by Raghunathrao for these four chiefs, ordering them to "seize" the Peshwa. The written order might have been altered before being delivered to the Gardi chiefs and the word "seize" might've been replaced with the word "slay" but the identity of the person who did this has remained a mystery. Meanwhile the Gardis chiefs were aware that the Peshwa could be slain if he were to offer armed resistance. When they conveyed these thoughts to Raghunathrao, he absolved them of any responsibility for the possible murder.[32]

Execution

Raghuji Angre of Kolaba had arrived in Pune to meet with the Peshwa and asked him to make a return visit on 30th August. And so Narayanrao along with Haripant Phadke rode to Angre's residence at around ten in the morning. Raghuji told Narayanrao during their conversational about the troubling rumours he had heard and warned him to be on his guard against danger to his life. After the meeting with Raghuji, Narayanrao and Phadke went to the Parvati temple to have their breakfast along with some guests who had been invited there. After the meal, the Peshwa and Haripant went back to the palace. Narayanrao told Haripant what he had heard from Raghuji and asked him to take the necessary steps to prevent any mischief. Haripant assured him that he would take care of the matter but first he had to attend to a mid-day meal with a friend. The Peshwa retired to his room in the palace. Meanwhile Tujali found out that the plot had been leaked and told the Gardi chiefs to immediately execute the plan or else everything could be ruined.[33]

At around one o'clock in the afternoon, five hundred soldiers led by the Gardi chiefs cut down the men guarding the hind gate and immediately rushed into the palace. They demanded payment of their long delayed salaries. The clerks and servants admonished the soldiers for the commotion and told them that their grievances would be listened to in the office. The soldiers responded by attacking the clerks; when one of them took shelter behind a cow, that used to be on the premises at all times for fresh milk, the soldiers cut down the animal and the man hiding behind it. They closed the front gate and proceeded to the Peshwa's room upstairs with their swords drawn and deafening shouts. The palace was packed with cries of horror and grief by the inmates but there was nothing they could do to stop the attack.[34]

Narayanrao was entirely unarmed at this time and in fear of his life he escaped through the back door to the appartment of his aunt Parvitabai, with whom he had a very close relationship as she had practically raised him since he was an infant. Parvatibai told him to go to his uncle as he could save his life. Narayanrao ran to his uncle who was performing his worship and held on to him, begging to be saved and even offering to make him Peshwa in exchange for being spared by the Gardi soldiers. Meanwhile Tulaji and Sumersinh who had closely followed Narayanrao arrived there and pulled him away from his uncle. Tulaji violently seized Narayanrao and Sumersinh hacked him to pieces. Narayanrao's servant Chapaji Tilekar fell upon his master's body to save him with some maids and they were all cruelly cut down. A little later Naroba Naik, an old and trusted man on palace duty, came forth and berated Raghunathrao for allowing such deplorable actions and he too was slain by the Gardis. Within a period of half an hour, eleven people had been killed in the palace, seven of them were Brahmin, two Maratha servants, two maids, besides one cow, no less sacred a life in the heart of a Brahman city.[35]

Aftermath

This act brought ill fame to the Peshwa administration, which was being looked after by the minister Nana Phadnavis. The Chief Justice of the administration, Ram Shastri Prabhune was asked to conduct an investigation into the incident, and Raghunathrao, Anandibai and Sumer Singh Gardi were all prosecuted in absentia. Although Raghunathrao was acquitted, Anandibai was declared an offender, and Sumer Singh Gardi the culprit. Sumer Singh Gardi died mysteriously in Patna, Bihar in 1775, and Anandibai performed Hindu rituals to absolve her sins. Kharag Singh and Tulaji Pawar were handed over by Hyder Ali back to the government and they were tortured to death. Swift punishment was given to the others too.[36]As the result of the murder, senior ministers and generals of the Maratha confederacy formed a regency council, known as the "Baarbhai Council", to conduct of the affairs of the state.[37] In the next political development, the posthumous son of Narayan Rao, who was named Sawai Madhav Rao II, was declared to be the “peshwa”. Raghunath Rao (Raghoba) fled away from the scene. The Baarbhai Council began to conduct the affairs of the state in the name of Sawai Madhav Rao II as he was a minor.

The new Peshwa lived only for 21 years and died in 1795. As he had no successor of his own blood, Baji Rao II (1796-1818) the son of Raghunathrao became the next Peshwa.

Legacy

- The Narayan Peth area in Pune is named after Peshwa Narayanrao.

- There is a belief in Pune that Narayanrao's ghost roams the ruins of Shaniwar Wada at every full moon night and calls out for help just like the way he did on the fateful day of his assassination .[38][39][40][41] Bajirao II believed in the ghost superstition too and planted thousands of mango trees around Pune city and gave donations to Brahmins and religious institutions in the hope that this would propitiate the ghost.[42]

- S. N. Patankar directed an early Indian silent film on the assassination of the Peshwa, titled Death of Narayanrao Peshwa, in 1915.[43]

References

- ^ "royalfamilyofindia -Resources and Information". www.royalfamilyofindia.com.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 14.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (2004). India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Permanent Black. pp. 89, 90, 91. ISBN 8178241099.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 14.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 13.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 13,14.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 15,16.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 19,20.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 23.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 17,18.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 18.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 14.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 20.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 24.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 17.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 18.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 18,19.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 20.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 19.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 20,21.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 21.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 21,22.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 22.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 15.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 16.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 16,17.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 19,20.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 22.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 22.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 24.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 23.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 24,25.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 25,26.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 26.

- ^ Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1948). New History of the Marathas Volume III: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772-1848). Phoenix Publications. p. 26,27.

- ^ S.Venugopala Rao (1977). power and criminality. Allied Publishers Pvt Limited. pp. 111–121.

- ^ Kulkarni, Sumitra (1995). The Satara Raj, 1818-1848: A Study in History, Administration, and Culture. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 74. ISBN 978-81-7099-581-4.

- ^ Preeti Panwar. "Top 10 most haunted places in India". Zee News. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ Huned Contractor (31 October 2011). "Going ghost hunting". Sakal. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ "Pune and its ghosts". Rediff. 19 July 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ "Security guard at historical Peshwa palace murdered". 2009.

A popular belief still prevails among people belonging to older generation here who claim that they had heard heart rending shouts of 'Kaka Mala Vachva' (Uncle please save me), at midnight emanating from the relics where Narayanrao Peshwa, one of the last heirs to the Peshwa throne, was slain on August 30, 1773 by 'Gardis' (royal guards) in a contract killing ordered by his uncle, Raghoba, in a power struggle.

- ^ S. G. Vaidya (1976). Peshwa Bajirao II and The Downfall of The Maratha Power. Pragati Prakashan. p. 249.

It was to propitiate the ghost of Narayanrao, that haunted him throughout his life, that the Peshwa planted thousands of mango trees around Poona, gave gifts to Brahmins and to religious establishments

- ^ Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. British Film Institute. Retrieved 12 August 2012.