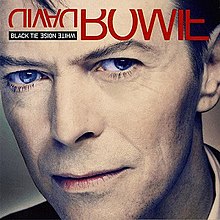

Black Tie White Noise

| Black Tie White Noise | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 5 April 1993 | |||

| Recorded | April–November 1992 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 56:24 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Producer |

| |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Black Tie White Noise | ||||

| ||||

Black Tie White Noise is the 18th studio album by English musician David Bowie, released on 5 April 1993 through Savage Records in the United States and Arista Records in the United Kingdom. The album was conceived following the disbandment of Bowie's rock band Tin Machine and his marriage to Somalian model Iman. It was recorded throughout 1992 between studios in Montreux, Los Angeles and New York City, with production handled by Bowie and Nile Rodgers, who previously co-produced 1983's Let's Dance. The two expressed enjoyment in the project initially, although Rodgers voiced dissatisfaction in later decades. The record features numerous guest appearances, including pianist Mike Garson and guitarist Mick Ronson, who had not worked with Bowie since the mid-1970s.

Inspired to write the title track after witnessing the 1992 Los Angeles riots, Black Tie White Noise is primarily separated into the themes of racial harmony and Bowie's marriage to Iman, which is reflected in multiple tracks. It features prevalent saxophone work from Bowie and a wide variety of musical styles, from art rock, electronic and soul, to jazz, pop and hip-hop influences. It also contains multiple instrumentals and cover versions. The album's lead single "Jump They Say" alludes to Bowie's step-brother Terry, who died in 1985.

Released amidst the rise of Britpop in the UK, Black Tie White Noise initially received favourable reviews from music critics, with some praising its experimentation, while others criticised its overall lack of cohesion. Some considered it Bowie's best work since Scary Monsters (1980). It debuted at number one on the UK Albums Chart, with each of its three singles reaching the UK top 40. Its promotion in America was stalled following the dissolution of Savage Records, resulting in the album becoming rare until later reissues. Bowie did not tour to support the album, instead releasing an accompanying film of the same name.

Black Tie White Noise marked the beginning of Bowie's commercial revival and improved critical standing following a string of poorly received projects. Nevertheless, it has received mixed assessments from critics and biographers in subsequent decades, with many praising Bowie's performance throughout but finding a lack of coherency. An interactive CD-ROM based on the album was released in 1994. It was reissued by EMI in 2003 and was remastered in 2021 as part of the box set Brilliant Adventure (1992–2001).

Background

Months after disbanding the rock band Tin Machine, whom he recorded with from 1988 to 1992,[1] David Bowie began recording material with his former Let's Dance (1983) collaborator Nile Rodgers.[2] The pair, who had reconnected in New York City after a Tin Machine concert in 1991,[3] first recorded "Real Cool World" for the animated film Cool World. It was released as a single in August 1992 and appeared on the film's accompanying soundtrack album,[4] and featured a sound that foreshadowed Bowie's direction for his next solo record.[2][5]

In October 1990, Bowie met Somalian model Iman in Los Angeles as he resumed recording with Tin Machine following the Sound+Vision Tour.[6] They married on 24 April 1992 in a private ceremony in Lausanne, Switzerland.[7][8] Five days later,[9] the two returned to Los Angeles to look for a new home together on the day the 1992 Los Angeles riots began,[3] forcing the newly-weds to stay in a hotel and witness the violence from inside.[8] Bowie later reflected: "It was an extraordinary feeling. I think the one thing that sprang into our minds was that it felt more like a prison riot than anything else. It felt as if innocent inmates of some vast prison were trying to break out, break free from their bonds."[10] According to biographer Nicholas Pegg, both the wedding and racial divide influenced Bowie's next album.[9] Bowie and Iman formalised their marriage in another ceremony in June, which featured numerous celebrity guests.[8]

Production

Recording history

With Bowie and Rodgers co-producing, recording for Black Tie White Noise took place between April and November 1992,[2] alternating between Mountain Studios in Montreux, Switzerland and the Hit Factory in New York City, with additional recording done at 38 Fresh studio in Los Angeles.[9] According to biographer Chris O'Leary, Bowie composed beats and patterns at 38 Fresh, which he sent to Rodgers at the Hit Factory to work them into songs.[2]

Both Bowie and Rodgers gave positive statements regarding the sessions in contemporary interviews.[9] Speaking with Rolling Stone, Bowie stated that the pair were not looking to do Let's Dance II, commenting that the two "would have done [that] years ago," which Rodgers agreed.[a][11] Rodgers described Bowie's attitude during the sessions as calmer than Let's Dance, "a hell of a lot more philosophical and just in a state of mind where his music was really, really making him happy".[12] Whereas Let's Dance took three weeks to record, Rodgers said Black Tie took "one year, more or less".[2] Further comparing the two, Rodgers commented that Let's Dance was the "easiest" record he ever made, while Black Tie was the hardest.[10] Bowie also had more involvement during the recording of Black Tie compared to Let's Dance, stating that the former was more "his vision" than Rodgers'.[9] In later years, however, Rodgers expressed disappointment in Black Tie, telling biographer David Buckley that he hated making it:[13]

I felt my hands were tied to a large extent ... I was playing great commercial licks to Bowie, and he was rejecting them almost across the board ... When we finished that record, I knew it wasn't cool...as Let's Dance. Don't get me wrong, I think there's really clever, interesting stuff on it. But the point is, it ain't as good as Let's Dance ... It was an exercise in futility.

According to Tin Machine member Reeves Gabrels, Bowie felt "pressured" into hiring Rodgers to produce the album. Rodgers was intent on creating a follow-up to Let's Dance, while Bowie wanted to pursue other musical directions.[14] Rodgers commented decades later that he wanted to make the album more "commercial", while Bowie was trying to "make this artistic statement about this period in his life".[15]

During the sessions, Bowie signed a contract with the American label Savage Records, affiliated with Arista Records and owned by Bertelsmann Music Group. Savage offered him the "artistic freedom" that he was craving: "[Studio head] David Nemran ... encouraged me to do exactly what I wanted to do, without any kind of indication that it would be manipulated, or that my ideas would be changed, or that other things would be required of me. That made me feel comfortable and that was the deciding factor."[9] Nemran replied that Bowie would be the label's breakthrough: "He's everything that I would use to describe us."[9]

Guest musicians

Black Tie White Noise features an array of guest musicians, some of whom had not collaborated with Bowie for decades. Guitarist Mick Ronson, a member of the Spiders from Mars backing band from 1971 to 1973, appears on a cover of Cream's "I Feel Free".[b][14] Ronson, whose last appearance was on 1973's Pin Ups,[c] was reconnected with Bowie, after the latter was impressed by the former's production work on Morrissey's Your Arsenal (1992).[2][18][17] Bowie praised Ronson's contributions on Black Tie while the latter commented, "I hope David's album does well. He's put everything into it."[17] Ronson died of cancer shortly after the album's release.[18]

Pianist Mike Garson, whose last appearance on a Bowie record was 1975's Young Americans, plays on "Looking for Lester".[19] Bowie told Record Collector magazine in 1993: "He really has a gift. He kind of plops those jewels on the track and they're quite extraordinary, eccentric pieces of piano playing."[20] Trinidadian guitarist Tony Springer (credited as "Wild T" Springer) appears on a cover of Morrissey's "I Know It's Gonna Happen Someday", which originally appeared on Your Arsenal. Bowie had met Springer in Canada during Tin Machine's It's My Life Tour and invited him to record. Bowie recalled that "he was an absolute delight", comparing his guitar style to Jimi Hendrix.[2][21]

Gabrels plays lead guitar on "You've Been Around", although his contribution was placed low in the mix.[2] The song was first attempted by Tin Machine during the sessions for their 1989 debut album, but Bowie was dissatisfied with the result so it was shelved, eventually rerecording it for Black Tie.[d][2][22] Singer Al B. Sure! duets with Bowie on the title track,[23] of which the two worked on the arrangement extensively, leading Bowie to quip "I've never worked longer with any artist than with Al B".[24]

Black Tie also features trumpet playing by Lester Bowie, whom David Bowie had wanted to work with throughout the 1980s. Lester's playing appears on six tracks, in which his contributions are considered by Pegg to be the album's "essential musical identity".[9] Lester played to tracks before he heard them, with David stating, "You roll the tape and he jumps in. Sometimes he's madly out of tune".[2] A foil to Lester's trumpet was David's saxophone, which appears more prominently on Black Tie than any other David Bowie album.[9] Rodgers found his saxophone playing challenging, telling Rolling Stone: "I think David would be the first to admit that he's not a saxophonist in the traditional sense. [...] He uses his playing as an artistic tool. He's a painter. He hears an idea, and he goes with it. But he absolutely knows where he's going..."[12] The album's horn arrangements were composed by Afro-Cuban jazz player Chico O'Farrill.[10] Black Tie also features several backing vocalists from the Let's Dance and 1986's Labyrinth, while pianist Philippe Saisse and producer David Richards returned from 1987's Never Let Me Down.[9]

Music and lyrics

I wanted to experiment on Black Tie, I love doing a hybrid of Eurocentric soul, but there were also pieces like "Pallas Athena" and "You've Been Around", which played more with ambience and funk.[2]

Bowie told Rolling Stone that his intent for Black Tie White Noise was making a new type of house record that brought back the "strong melodic content" of the 1960s, finding "the new R&B [of today]" a mixture of "hip-hop and house".[11] He commented: "I think this album comes from a very different emotional place. That's the passing of time, which has brought maturity and a willingness to relinquish full control over my emotions."[11] Indeed, reviewers have noted a wide variety of musical influences present throughout the record.[15][23] Biographer Christopher Sandford noted the presence of soul, rap, disco and pop,[8] while author James Perone found hip-hop rhythms, avant-garde jazz, gospel and references to Bowie's plastic soul work of the 1970s.[23] Rolling Stone's Jason Newman described the music as "a blend of Euro-disco, techno-rock, freestyle jazz, Middle Eastern riffs and hip-hop".[15] Writing for AllMusic, Stephen Thomas Erlewine considered Black Tie an "urban soul record" that balances styles of the "commercial dance rock" of Let's Dance with the art rock of the late 1970s Berlin Trilogy.[25] A writer for The Economist later categorised Black Tie as art rock and electronic.[26]

Black Tie White Noise is primarily separated into two major themes: racial harmony and Bowie's marriage to Iman. Perone finds the "Black Tie" represents "a wedding" while "White Noise" represents the "instrumentally focused, slightly experimental jazz pieces".[23] A firsthand eyewitness account of the Los Angeles riots inspired Bowie to write the title track.[8] Meanwhile, for his wedding ceremony, he composed an instrumental intended to fuse him and Iman's English and Somalian cultures.[7] Writing the piece triggered Bowie to make the album:[3][12]

Writing [the music for the wedding] brought my mind around to, obviously, what commitment means and why I was getting married at this age and what my intentions were and were they honorable? [laughs] And what I really wanted from my life from now on. I guess it acted as a watershed to write a lot of quite personal things, putting together a collection of songs that illustrated what I'd been going through over the past three or four years.

Songs

Black Tie White Noise opens with the instrumental "The Wedding",[2][23] a funk adaptation of the instrumental Bowie composed for his wedding. It's a piece that, in Pegg's words, "fuses dance beats, distant backing vocals and Eastern-influenced saxophone cadences" that set the stage for the remaining tracklist.[7] The Black Tie version of "You've Been Around" blends contemporary dance music with elements of jazz.[23] Although Bowie and Gabrels wrote it together, the new version, in O'Leary's words, "effectively erased...Reeves Gabrels".[2] Pegg states that the lyrics foreshadow the "fractal images" Bowie would use for his next studio album, Outside (1995).[22] Bowie's cover of "I Feel Free" is described by Pegg as "techno-funk",[17] while Perone notes it as considerably different from the original, being more akin to "1990s dance music".[23]

Bowie's goal for the title track was to avoid ending up like "an 'Ebony and Ivory' for the Nineties".[11] As such, it was recorded with a rougher edge, featuring crackles throughout. To evoke the racial theme, the lyrics reference "We Are the World" by the supergroup USA for Africa (1985) and Marvin Gaye's "What's Going On" (1971);[23] Pegg notes that the "black and white voices" of Al B Sure! assist in the theme's presentation.[24] Musically, the track is funky, while David and Lester Bowie shine on saxophone and trumpet, respectively.[23] "Jump They Say" discusses themes of mental illness,[23] and is loosely based on David's step-brother Terry Burns, who committed suicide after being hospitalised for schizophrenia in the 1980s.[e][28] Bowie stated, "It's the first time I've felt capable of addressing it."[11][3] Described by Buckley as "an eerie psychodrama",[13] the song features prevalent backwards saxophone work from Bowie.[28]

"Nite Flights" was written by singer-songwriter Scott Walker (as Scott Engel) and originally recorded by the Walker Brothers for their 1978 album of the same name. Bowie was a huge fan of the album, first hearing it while recording 1979's Lodger,[2] and decided to cover the song for Black Tie White Noise.[29] Musically, Pegg describes it as a "Euro-disco/jazz-funk fusion" evocative of the Berlin Trilogy, while it lyrically predates the content found on Outside.[29] Buckley praises it as Bowie's "best musical moment in a decade".[13] "Pallas Athena" is largely an instrumental that is reminiscent of Bowie's Berlin work,[23] leading Buckley to consider it Bowie's most experimental work in a decade.[13] Musically, it fuses elements of "contemporary hip-hop dance rhythms" with the ambience of Low (1977).[23][30] Bowie told NME in 1993 that he "[didn't] know what the fuck it's about".[30]

Both "Miracle Goodnight" and "Don't Let Me Down & Down" support the wedding theme. The former is laden with synthesisers and according to Perone, mimics "conventional 1980s pop".[2][23] The latter was originally recorded in Arabic by Mauritanian singer Tahra Mint Hembara (a friend of Iman's) in 1988 as "T Beyby"; her producer Martine Valmont wrote English lyrics and retitled it "Don't Let Me Down & Down". Bowie discovered it while browsing through Iman's CD collection and decided to cover it as a wedding gift. He recalled, "[It was] one of those tracks that sort of in a diary-like way records the beginnings of a relationship."[2][31] O'Leary compares its arrangement to Tonight (1984) and calls it the "most obscure" cover of Bowie's entire career.[2] Pegg states that it recalls the "romantic balladry" of "Win" and "Can You Hear Me?" from Young Americans.[31]

Perone calls the instrumental "Looking for Lester" "credible mid-1990s jazz".[23] It features David and Lester Bowie soloing on saxophone and trumpet, respectively. The title was a play on John Coltrane's "Chasing the Train".[2][19] The gospel cover of "I Know It's Gonna Happen Someday" is reminiscent of Bowie's early 1970s ballads, including a direct reference to the climax of "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" (1972). Pegg describes the track as "Bowie covers Morrissey parodying Ziggy Stardust in the style of Young Americans".[32][21] Black Tie White Noise ends with a vocal version of the opening track, titled "The Wedding Song".[2][23] Pegg considers the two tracks "direct throwbacks" to "It's No Game", which bookends Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (1980).[9]

Artwork and title

The cover artwork was taken by photographer Nick Knight. Additionally, the inlay photography depicts Bowie in attire from the "Never Let Me Down" music video: shirtsleeves with a Bogey hat holding a 1940s microphone.[9] According to Buckley, the title was a comment on the racial mix of Bowie and Iman's marriage and the fusion of American and British musical styles Bowie was experimenting with. It was also in debt to the cut-up technique Bowie had discussed in an interview with writer William S. Burroughs in the mid-1970s.[13] A working title for the album was The Wedding Album.[16][15] On the title, Bowie told Record Collector:[20]

White noise itself is something that I first encountered on the synthesiser many years ago. There's black noise and white noise. I thought that much of what is said and done by the whites is white noise. 'Black ties' is because, for me, musically, the one thing that really turned me on to wanting to be a musician, wanting to write, was black music, American black music [...] I found it all very exciting – the feeling of aggression that came through the arrangements.

Release and promotion

By the end of 1992, the rise of Britpop bands such as Blur, the Auteurs and Suede had influenced the UK music scene.[9] These bands, particularly Suede, acknowledged Bowie's influence in interviews and their music, with Buckley describing Suede's debut single "The Drowners" as an homage to Bowie's glam rock work of the early 1970s.[f][13][33] Shortly before the release of Suede's debut album and Black Tie White Noise, NME's Steve Sutherland interviewed Bowie and Suede's lead singer Brett Anderson together, where the two discussed influences and exchanged compliments. The interview generated a large amount of publicity for the two artists' upcoming albums in the UK.[9] Additionally, biographer Paul Trynka states that Ronson's guest appearance garnered Black Tie White Noise more attention.[14]

The lead single, "Jump They Say" backed by a remix of "Pallas Athena", was released on 15 March 1993.[2][34] It came in numerous formats that contained various remixes of the track, a trend that would continue in Bowie's work throughout the rest of the 1990s.[9] The single became the artist's biggest hit since "Absolute Beginners" seven years earlier, peaking at number nine on the UK Singles Chart.[10] It was supported by a Mark Romanek-directed music video featuring numerous references to Bowie's prior work.[13] Pegg calls it one of Bowie's finest videos, praising its "non-linear" imagery.[28]

Black Tie White Noise was issued on 5 April 1993 by Savage Records in the US and Arista Records in the UK on different LP and CD formats, with the catalogue numbers 74321 13697 1 and 74321 13697 2, respectively.[9][35] It was Bowie's first solo album since Never Let Me Down six years earlier.[16] The LP release removed "The Wedding" and "Looking for Lester",[9] while the CD edition featured a remix of "Jump They Say" and the outtake "Lucy Can't Dance".[g][23][35] Meanwhile, the Japanese and Singaporean CDs contained a remix of "Pallas Athena" and "Don't Let Me Down & Down", respectively.[9] Before its release, Bowie expressed love for the album, stating, "I don't think I've hit this peak before as a performer and a writer."[11]

The album was a commercial success in the UK, entering the UK Albums Chart at number one and dethroning Suede's debut album.[9] It was Bowie's final UK number one album until The Next Day in 2013.[36] In America however, Savage filed for bankruptcy shortly after the album's release, affecting its promotion in the country. Although Bowie had signed a three-album deal, the label sued Bowie claiming substantial losses on Black Tie. The case was dismissed, leading to the label's dissolution.[13][10] Nevertheless, it managed to peak at number 39 on the Billboard 200 before temporarily becoming a rarity in record stores until later reissues in the 1990s.[9][37]

The title track, backed by a remix of "You've Been Around", was released as the second single in June 1993;[34][35] it was credited to David Bowie featuring Al B. Sure![24] It peaked at number 36 in the UK,[35] and was supported by a music video also directed by Romanek, which featured both Bowie and Al B. Sure! and displayed, in Pegg's words, "a deft bricolage of images against the backdrop of an urban ghetto."[24] "Miracle Goodnight", backed by "Looking for Lester", was issued as the third and final single in October 1993. It peaked at number 40 in the UK.[34][35] Pegg argues that it would have been a bigger hit had it been the lead single.[38] "Nite Flights" was intended as the fourth single, but was cancelled by Arista following the performances of the two previous singles.[10] Meanwhile, "Pallas Athena" was remixed by numerous DJs and anonymously became a popular club track in London and New York City.[2]

Critical reception

| Initial reviews (in 1993) | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Entertainment Weekly | D[40] |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| The Press and Journal | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Village Voice | B−[44] |

Black Tie White Noise received generally favourable reviews from music critics on release.[23] Some reviewers considered it Bowie's finest since Scary Monsters.[3][9] Sandford states that some praised its experimentation, while others criticised its overall lack of cohesion.[8] David Sinclair of Q magazine praised the album, writing: "Black Tie White Noise is an album which picks up where Scary Monsters left off in 1980, and if any collection of songs could reinstate [Bowie's] godhead status, then this is it."[45] Sinclair felt the record was full of "imagination and charm", further calling Bowie's saxophone performances some of his best to date. He primarily criticised the lack of "obvious" hit singles.[45] A reviewer for Billboard was also positive, describing it as a whole "trail-blazing and brilliant", further noting "inspired covers" and echoes of Let's Dance, Scary Monsters and Ziggy Stardust (1972).[46] Meanwhile, Rolling Stone's Paul Evans called it "one of the smartest records of a very smart career", finding references to the artist's previous works as well as new innovations that "point the way to future risk, to brave changes yet to come".[43] Richard Cromelin of the Los Angeles Times expressed similar sentiments, calling it Bowie's "most committed-sounding music in years".[41]

Other reviewers were more negative in their assessments. A reviewer for Vox magazine found the radio-friendly singles calculated and Bowie's saxophone playing inferior to his musical contributions on "Heroes" (1977), but felt its "bent, ethnic-sounding notes create the album's most atmospheric moments".[9] Dave Thompson considered it a "very straight album" in The Rocket, noting a general lack of innovation.[47] Meanwhile, Ken Tucker of Entertainment Weekly described Black Tie as "stultifying yet annoying", along with mostly "listless" and "tired" save for "Miracle Goodnight" and "I Know It's Gonna Happen Someday".[40] Veteran critic Robert Christgau, writing in The Village Voice, said that the music was Bowie's "most arresting" because of its dance beats and electronic textures, but reacted negatively towards Bowie's lyrics.[44]

Aftermath and legacy

| Retrospective reviews (after 1993) | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Pitchfork | 6.8/10[50] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 1/10[52] |

| Uncut | |

Bowie did not tour in support of Black Tie White Noise, telling Record Collector: "It takes up so much time. [...] I think I lost such a lot of my life through doing that."[20] He also declined an invitation to perform on MTV's Unplugged programme. Instead, he made small appearances on American television and released a film to accompany the album.[9] Directed by Bowie's long-time video director David Mallet, David Bowie: Black Tie White Noise (1993) is a hybrid of interviews, footage shot during the album sessions and mimed performances of six tracks that were shot by Mallet on 8 May 1993 at Hollywood Center Studios. Pegg calls it a "useful companion" to the album but finds Mallet's material as "unimaginative".[54] Sandford also considers the Mallet-directed material inferior to the two men's prior collaborations.[32] The film was included as part of EMI's 2003 reissue campaign for the album, with a standalone DVD release following two years later.[54] Although Bowie intended to resume the Tin Machine project following the release of Black Tie,[3][11] the idea never came to fruition. His next effort was the solo The Buddha of Suburbia (1993).[55]

Black Tie White Noise marked the beginning of Bowie's commercial revival and improved critical standing,[12][56] with one reviewer later calling it a "perfect" way to begin the "next stage" of Bowie's career.[57] Despite its initial success, the album has been given mixed assessments from reviewers in later decades. In a positive review, David Quantick of BBC Music recognised it as a continuation of Scary Monsters, wherein he used aspects of his entire career in new, innovative ways. He credited the production quality and Bowie's "immense confidence" for an album that rose above its immediate predecessors.[57] In AllMusic, Erlewine admitted that it was his best since Scary Monsters at the time, but felt the record lacked cohesion. Despite containing production that "sounded dated within two years", he identified ideas that Bowie would further expand with on later releases. He ultimately called it "an interesting first step in Bowie's creative revival".[25] On the other hand, Linda Levitt of Spectrum Culture found the entire album cohesive, writing that "the songs hang together as one of those albums that can be listened to all the way through, flowing from one to the next".[58] In a 2016 retrospective ranking all of Bowie's 26 studio albums from worst to best, Bryan Wawzenek of Ultimate Classic Rock placed Black Tie White Noise at number 25 (above Never Let Me Down). He noted that although it was initially hailed as a comeback record, he argued that it "hasn't aged well".[59] In a 2018 list which included Bowie's two albums with Tin Machine, the writers of Consequence of Sound ranked Black Tie White Noise number 18 out of 28. David Sackllah wrote that the record holds up "fairly well" and, as the beginning of an experimental era, Black Tie "stood as one of his better works from the decade".[60]

Bowie's biographers have also given Black Tie White Noise mixed reactions. Pegg argues that it may have initially been "over-praised", despite being at the time "without a doubt" Bowie's best since Scary Monsters. He states: "It's a supremely confident, professional and commercial piece of work, and its best moments are exceptional," concluding that although its follow-ups were improvements, Black Tie was "a step in the right direction".[9] Both Buckley and Sandford praise Bowie's vocal performance throughout the record,[32] with the former also finding a "certain charm" to it, highlighting Lester Bowie's trumpet playing but finding the lyrics among David Bowie's weakest.[13] Meanwhile, Perone criticises its lack of coherence while also notes it as a transitional album.[23] Marc Spitz considers it among Bowie's "lesser work", but nonetheless finds "flashes of brilliance".[18] Trynka highlights "Jump They Say" and "Miracle Goodnight" as standouts, but finds that its overall "overpolite, airbrushed sheen" meant that following the fall of Savage Records, "little bemoaned its passing".[61] Like Trynka, Dave Thompson highlights individual tracks as standouts, naming "Don't Let Me Down & Down", "Nite Flights" and "Jump They Say", but overall finds the album as a whole disappointing, calling it "at best", Bowie's "least-bad album since Let's Dance".[10]

CD-ROM and reissues

In 1994, an "interactive CD-ROM" based on Black Tie White Noise was developed by ION and released by MPC. The CD-ROM, which Bowie intended to be "fully interactive", gave users a chance to remake the "Jump They Say" video using pre-existing footage and view excerpts from the Black Tie White Noise film.[62][63][64] It was not well received,[65] although Perone considered it innovative for its time.[23] Bowie initially expressed excitement in the project,[66] but it ultimately did not live up to his expectations, stating in 1995 that he "absolutely loathed it".[67]

In August 2003, Black Tie White Noise was reissued by EMI in a 3-CD deluxe edition to mark its tenth anniversary. It featured the original album, a CD of remixes and other tracks from the period (such as "Real Cool World"), and the original Black Tie White Noise film.[9] In 2021, the album was remastered and included as part of the box set Brilliant Adventure (1992–2001).[68][69]

Track listing

All tracks are written by David Bowie, except where noted

| No. | Title | Lyrics | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Wedding" | instrumental | 5:04 | |

| 2. | "You've Been Around" | Bowie, Reeves Gabrels | 4:45 | |

| 3. | "I Feel Free" (featuring Mick Ronson) | Pete Brown | Jack Bruce | 4:52 |

| 4. | "Black Tie White Noise" (featuring Al B. Sure!) | 4:52 | ||

| 5. | "Jump They Say" | 4:22 | ||

| 6. | "Nite Flights" | Noel Scott Engel | Engel | 4:30 |

| 7. | "Pallas Athena" | 4:40 | ||

| 8. | "Miracle Goodnight" | 4:14 | ||

| 9. | "Don't Let Me Down & Down" | Tahra Mint Hembara, trans. Martine Valmont | Hembara | 4:55 |

| 10. | "Looking for Lester" | instrumental | Bowie, Nile Rodgers | 5:36 |

| 11. | "I Know It's Gonna Happen Someday" | Morrissey | Mark E. Nevin | 4:14 |

| 12. | "The Wedding Song" | 4:29 | ||

| Total length: | 56:33 | |||

| No. | Title | Remixer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13. | "Jump They Say" (alternate mix) | JAE-E | 3:58 |

| 14. | "Pallas Athena" (Don't Stop Praying mix) | Meat Beat Manifesto | 5:37 |

| 15. | "Lucy Can't Dance" | 5:45 | |

| Total length: | 15:20 (71:53) | ||

Notes

- "Jangan Susahkan Hatiku" ("Don't Let Me Down & Down" with the first half-sung in Indonesian) supplanted "Don't Let Me Down & Down" in the version of the album released in Indonesia.

- Nile Rodgers was not given a co-writing credit for "Looking for Lester" on the original 1993 release, but his credit was added on the 2003 reissue.

Personnel

According to the liner notes and biographer Nicholas Pegg.[70][71]

- David Bowie – vocals, guitar, saxophone, dog alto

- Nile Rodgers – guitar

- Poogie Bell, Sterling Campbell – drums

- Barry Campbell, John Regan – bass

- Richard Hilton, Dave Richards, Philippe Saisse, Richard Tee – keyboards

- Michael Reisman – harp, tubular bells, string arrangement

- Gerardo Velez – percussion

- Fonzi Thornton, Tawatha Agee, Curtis King, Jr., Dennis Collins, Brenda White-King, Maryl Epps – background vocals

- Al B. Sure! – vocal duet on "Black Tie White Noise"

- Reeves Gabrels – lead guitar on "You've Been Around"

- Mick Ronson – lead guitar on "I Feel Free"

- Wild T. Springer – lead guitar on "I Know It's Gonna Happen Someday"

- Mike Garson – piano on "Looking for Lester"

- Lester Bowie – trumpet on "You've Been Around", "Jump They Say", "Pallas Athena", "Don't Let Me Down & Down" and "Looking for Lester"

- Fonzi Thornton, Tawatha Agee, Curtis King, Jr., Dennis Collins, Brenda White-King, Maryl Epps, Frank Simms, George Simms, David Spinner, Lamya Al-Mughiery, Connie Petruk, David Bowie, Nile Rodgers – choir on "I Know It's Gonna Happen Someday"

Production

- David Bowie – producer

- Nile Rodgers – producer

- Jon Goldberger, Gary Tole, Andrew Grassi, Mike Greene, Louis Alfred III, Dale Schalow, Lee Anthony, Michael Thompson, Neal Perry, Andy Smith – engineering

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

Certifications

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ^ O'Leary notes that Bowie's previous attempt to create Let's Dance II resulted in 1984's Tonight.[2]

- ^ "I Feel Free" was a longtime favourite of Bowie's, who performed it frequently with the Spiders from Mars in 1972.[13] The song was initially shortlisted for his 1973 covers album Pin Ups before it was dropped. Another version was recorded during the sessions for Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (1980); a backing track was completed before the idea was scrapped.[17]

- ^ Before Black Tie, Bowie and Ronson appeared on stage together at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert in April 1992.[17]

- ^ Gabrels would later rerecord "You've Been Around" for his 1995 solo album The Sacred Squall of Now.[2]

- ^ Terry Burns was a major influence on Bowie in the early 1970s;[10] his presence is felt on numerous tracks from both The Man Who Sold the World (1970) and Hunky Dory (1971).[27] Bowie also covered "I Feel Free" on Black Tie as a tribute to Terry, who took Bowie to a Cream concert in London in the 1960s.[13]

- ^ Buckley and Pegg also acknowledge Suede's second album Dog Man Star as a tribute to the titles of three early 1970s Bowie works, while their 1999 album Head Music was influenced by Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (1980).[9][13]

- ^ Rodgers was annoyed that Bowie relegated "Lucy Can't Dance" to a bonus track, telling Buckley it was "a guaranteed number one record" and that he was "already accepting [his] Grammy!"[13]

References

- ^ O'Leary 2019, chap. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w O'Leary 2019, chap. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f Sullivan, Jim (12 April 1993). "New wife, new album keep David Bowie in fine spirits". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 784.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 219.

- ^ Sandford 1997, pp. 288–289.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 304–305.

- ^ a b c d e f Sandford 1997, pp. 299–302.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Pegg 2016, pp. 417–421.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thompson 2006, chap. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wild, David (21 January 1993). "Bowie's Wedding Album". Rolling Stone. p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Sinclair, David (1993). "Station to Station". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2013 – via davidbowie.se.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Buckley 2005, pp. 413–421.

- ^ a b c Trynka 2011, pp. 429–432.

- ^ a b c d e Newman, Jason (6 April 2016). "Watch David Bowie's 'Black Tie White Noise,' Inspired by L.A. Riots". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ a b c DeRiso, Nick (5 April 2018). "25 Years Ago: David Bowie Opens Up on 'Black Tie White Noise'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Pegg 2016, p. 120.

- ^ a b c Spitz 2009, pp. 355–356.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 171.

- ^ a b c Paytress, Mark (1993). "David Bowie Back in Black (and White)". Record Collector. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 321–322.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Perone 2007, pp. 107–112.

- ^ a b c d Pegg 2016, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b c Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Black Tie White Noise – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ "David Bowie's genre-hopping career". The Economist. 12 January 2016. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ O'Leary 2019, pp. 349–351.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 200.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 206.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b c Sandford 1997, pp. 303–311.

- ^ Spitz 2009, p. 368.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 784–785.

- ^ a b c d e O'Leary 2019, Partial Discography.

- ^ Smith, Caspar Llewellyn (18 March 2013). "David Bowie tops albums chart for first time in 20 years". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Sprague, David (February 1997). "David Bowie Interview". Pulse!. Sacramento, California. pp. 34–37, 72–73.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Kot, Greg (9 April 1993). "All Dressed Up . . .: Bowie's 'Black Tie' Tries To Go Everywhere But Ends Up Nowhere". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b Tucker, Ken (16 April 1993). "Black Tie White Noise Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ a b Cromelin, Richard (4 April 1993). "Album Review". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Smith, Steve (9 April 1993). "Sounds Around". The Press and Journal.

- ^ a b Evans, Paul (29 April 1993). "Black Tie White Noise Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 15 March 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (23 November 1993). "Turkey Shoot". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ a b Sinclair, David (May 1993). "David Bowie: Black Tie White Noise". Q. Retrieved 31 October 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ "Album Reviews" (PDF). Billboard. 10 April 1993. p. 50. Retrieved 31 October 2021 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (May 1993). "David Bowie: Black Tie, White Noise". The Rocket. Retrieved 31 October 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ "Black Tie White Noise – Blender". Blender. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Bowie, David". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). London: Omnibus Press. p. 2795. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- ^ Collins, Sean T. (11 December 2021). "David Bowie: Brilliant Adventure (1992–2001) Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (2004). "David Bowie". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York City: Simon & Schuster. pp. 97–98. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Sheffield 1995, p. 55.

- ^ Staff (1 October 2003). "David Bowie – Black Tie, White Noise". Uncut. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 644.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 421–422.

- ^ Potter, Matt (11 January 2013). "Hello Again, Spaceboy". Sabotage Times. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ^ a b Quantick, David (2011). "Review of David Bowie Black Tie White Noise". BBC Music. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Levitt, Linda (5 November 2020). "Discography: David Bowie: Black Tie White Noise". Spectrum Culture. Archived from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Wawzenek, Bryan (11 January 2016). "David Bowie Albums Ranked Worst to Best". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 1 October 2020 suggested (help) - ^ Sackllah, David (8 January 2018). "Ranking: Every David Bowie Album From Worst to Best". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Trynka 2011, p. 493.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 705.

- ^ Sandford 1997, p. 307.

- ^ O'Leary 2019, chap. 9.

- ^ Burr, Ty (17 June 1994). "Jump: The David Bowie Interactive CD-ROM". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (28 July 1994). "The Pop Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ Paul, George A. (1995). "Bowie Outside Looking In". Axcess. Vol. 3, no. 5. pp. 60–62.

- ^ "Brilliant Adventure and TOY press release". David Bowie Official Website. 29 September 2021. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Marchese, Joe (29 September 2021). "Your Turn to Drive: Two David Bowie Boxes, Including Expanded 'Toy,' Announced". The Second Disc. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Black Tie White Noise (CD booklet). David Bowie. Europe: Arista Records. 1993. 74321 13697 2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 417–418.

- ^ "David Bowie – Black Tie White Noise". australian-charts.com. Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "David Bowie – Black Tie White Noise" (ASP). austriancharts.at. Ö3 Austria Top 40. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Top Albums/CDs – Volume 57, No. 16, May 01 1993". RPM. 1 May 1993. Archived from the original (PHP) on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "David Bowie – Black Tie White Noise" (ASP). dutchcharts.nl. MegaCharts. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "1993 Year-End Sales Charts - Eurochart Hot 100 Albums 1993" (PDF). Music & Media. 18 December 1993. p. 15. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2021). "David Bowie". Sisältää hitin - 2. laitos Levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla 1.1.1960–30.6.2021 (PDF) (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava. pp. 36–37.

- ^ "InfoDisc : Tous les Albums classés par Artiste > Choisir Un Artiste Dans la Liste". infodisc.fr. SNEP. Archived from the original (PHP) on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Album Search: David Bowie – Black Tie White Noise" (in German). Media Control. Archived from the original (ASP) on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ Racca, Guido (2019). M&D Borsa Album 1964–2019 (in Italian). ISBN 9781094705002.

- ^ "Highest position and charting weeks of Black Tie White Noise by David Bowie". oricon.co.jp (in Japanese). Oricon Style. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "David Bowie – Black Tie White Noise" (ASP). charts.nz. Recording Industry Association of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 21 May 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "David Bowie – Black Tie White Noise" (ASP). norwegiancharts.com. VG-lista. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "David Bowie – Black Tie White Noise" (ASP). swedishcharts.com. Sverigetopplistan. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "David Bowie – Black Tie White Noise" (ASP). hitparade.ch. Swiss Hitparade. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "David Bowie | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "RPM Top 100 Albums of 1993". RPM. 18 December 1993. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Dutch charts jaaroverzichten 1993". dutchcharts.nl (in Dutch). MegaCharts. Archived from the original (ASP) on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b Oricon Album Chart Book: Complete Edition 1970–2005. Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. 2006. ISBN 4-87131-077-9.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums 1993" (PDF). Music Week. 15 January 1994. p. 25. Retrieved 20 April 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – David Bowie – Black Tie White Noise". Music Canada. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Japanese album certifications – デヴィッド・ボウイ – ブラック・タイ・ホワイト・ノイズ" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Retrieved 10 October 2013. Select 1997年2月 on the drop-down menu

- ^ "British album certifications – David Bowie – Black Tie White Noise". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

Sources

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-75351-002-5.

- O'Leary, Chris (2019). Ashes to Ashes: The Songs of David Bowie 1976–2016. London: Repeater. ISBN 978-1-91224-830-8.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Perone, James E. (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27599-245-3.

- Sandford, Christopher (1997) [1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. London: Time Warner. ISBN 978-0-306-80854-8.

- Sheffield, Rob (1995). "David Bowie". In Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig (eds.). Spin Alternative Record Guide. Vintage Books. pp. 55–57. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Thompson, Dave (2006). Hallo Spaceboy: The Rebirth of David Bowie. Toronto: ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-733-8.

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-31603-225-4.

External links

- Black Tie White Noise at Discogs (list of releases)