SUMKA

National Socialist Workers Party of Iran حزب سوسیالیست ملی کارگران ایران | |

|---|---|

| Abbreviation | SUMKA |

| Leader | Davud Monshizadeh |

| Spokesperson | Shapour Zandnia |

| Founded | April 1952[1] |

| Headquarters | "Black House", Khaneqah Street, Tehran[1] |

| Membership (1952) | 600[1] |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-right[1] |

| Party flag | |

| |

The National Socialist Workers Party of Iran[1] (Template:Lang-fa), better known by its abbreviation SUMKA (Template:Lang-fa), is a National Socialist[3] party in Iran.

Foundation

The party was formed in 1940 by Davud Monshizadeh[4] and had a minor support base in Iranian universities.[citation needed] Critics of the late Mohammad Reza Pahlavi allege that he provided direct funding to the SUMKA at one point.[5]

Development

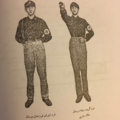

Monshizadeh formed the SUMKA in 1952 along with Morteza Kossarian.[6] Monshizadeh had lived in Germany since 1937, and was a former SS member, who fought and was wounded in the Battle of Berlin. Kossarian was also a former SS Officer, who was part of the planning of Operation Barbarossa and subsequently fought at the Battle of Kiev and the Battle of Stalingrad, where he was injured. Monshizadeh was also a professor at Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich and was deeply influenced by Jose Ortega y Gasset's philosophy. The SUMKA briefly attracted the support of young nationalists in Iran, including Dariush Homayoon, an early member who would later rise to prominence in the country.[5] SUMKA adopted the swastika and black shirt as part of their uniforms.[5][7]

They were firmly opposed to the rule of Mohammed Mossadegh during their brief period of influence, and the party worked alongside Fazlollah Zahedi in his opposition to Mossadegh. In 1953, they were part of a large group of Zahedi supporters who marched towards the palace of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi demanding the ousting of Mossadegh.[8] The party would become associated with street violence against the supporters of Mossadegh and the Tudeh Party.[1]

Shock troops

The party had an "assault group" (guruhe hamle) with an estimated size of 100 members that openly attacked members of the communist Tudeh Party of Iran and the Soviet Cultural Center and Hungarian Trade Office in Tehran. Colonel Fateh, a retired officer of the Imperial Iranian Air Force, was responsible for training the unit.[1]

Financial sources

Colonel Fateh was the official patron of the SUMKA.[1] After the 1953 Iranian coup d'état, the party received a monthly stipend of 2,500 Iranian rial from the police and other security authorities. In 1958, Monshizadeh received $7,000 from SAVAK to go to the United States.[1] The party was also possibly financed by foreign embassies based in Iran.[1] In April 1952, Iranian police reported that Monshizadeh was seeking to establish ties with the British embassy to get financial support. It was allegedly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) through TPBEDAMN.[1][9]

Legacy

Advocates of Nazism continue to exist in Iran and are active mainly on the Internet.[10] As of 2010, they are reported to be a small yet slowly increasing minority of Iranian youths internationally.[11]

Gallery

Party branches

-

SUMKA – Iran Youth branch

-

SUMKA – assault group

-

SUMKA – Technical unit

-

Immortal unit and Leader emblem

Image Gallery

-

SUMKA Uniform Diagram for Shock Troops and Guard

-

Davud Monshizadeh with SUMKA members

-

Davud Monshizadeh in an undated photo

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Rahnema, Ali (24 November 2014). Behind the 1953 Coup in Iran: Thugs, Turncoats, Soldiers, and Spooks. Cambridge University Press. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-1107076068.

- ^ a b Bashiriyeh, Hossein (27 April 2012). The State and Revolution in Iran (RLE Iran D). Taylor & Francis. p. 14. ISBN 9781136820892.

- ^ Dabashi, Hamid (2015). Persophilia: Persian Culture on the Global Scene. Harvard University Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780674504691.

- ^ Leonard Binder, Iran: Political Development in a Changing Society, University of California Press, 1962, p. 217

- ^ a b c Hussein Fardust, The Rise and Fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty: Memoirs of Former General Hussein, p. 62

- ^ Monshizadeh, Davud. Fight With Evil Series One: Principles of the Second Office Eagle.

- ^ Homa Katouzian, Musaddiq and the Struggle for Power in Iran, I.B. Tauris, 1990, p. 89

- ^ Mark J. Gasiorowski, 'The 1953 Coup D'etat in Iran', International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 19, No. 3. (Aug., 1987), p. 270

- ^ Mark J. Gasiorowski (2004). "The 1953 Coup d'État Against Mosaddeq". In Mark J. Gasiorowski; Malcolm Byrne (eds.). Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-8156-3017-3. JSTOR j.ctt1j5d815.

- ^ Maryam Sinaiee (24 November 2010), "Iranian ministry denies authorising neo-Nazi website", The National, archived from the original on 9 October 2017, retrieved 5 October 2017

- ^ Lorena Galliot (18 November 2010), "Who's behind the 'Association of Iranian Nazis'", France 24, archived from the original on 3 October 2017, retrieved 5 October 2017

- 1952 establishments in Iran

- Anti-Arabism in Asia

- Anti-capitalist political parties

- Anti-communist parties

- Antisemitism in Iran

- Far-right political parties

- Fascism in Iran

- Iranian nationalism

- Nationalist parties in Iran

- Neo-Nazi political parties

- Neo-Nazism in Asia

- Political parties established in 1952

- Political parties in Pahlavi Iran (1941–1979)

- Anti-Islam sentiment in Iran